Are Countries Ready for REDD+ Payments? REDD+ Readiness in Bhutan, India, Myanmar, and Nepal

Abstract

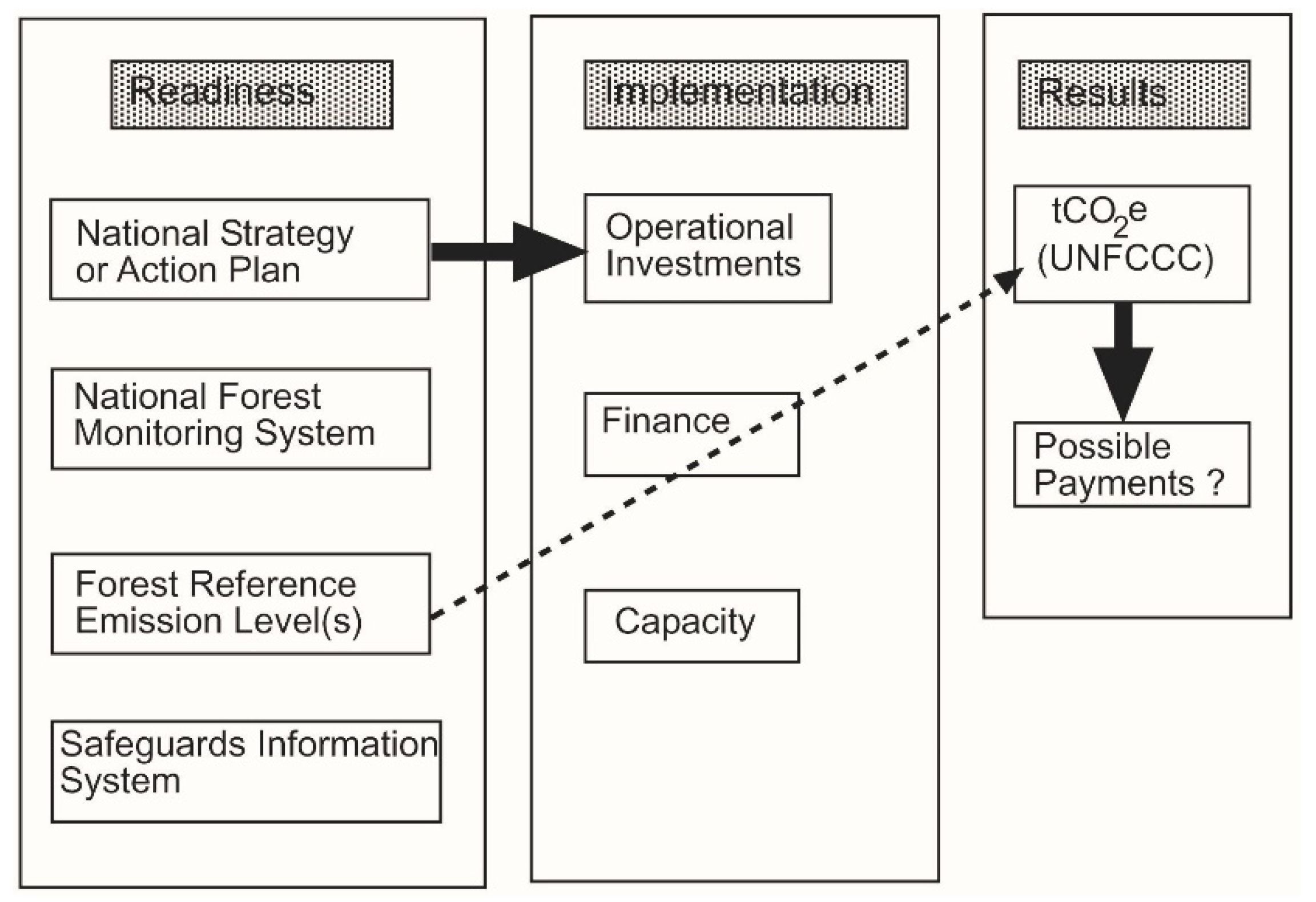

1. Introduction

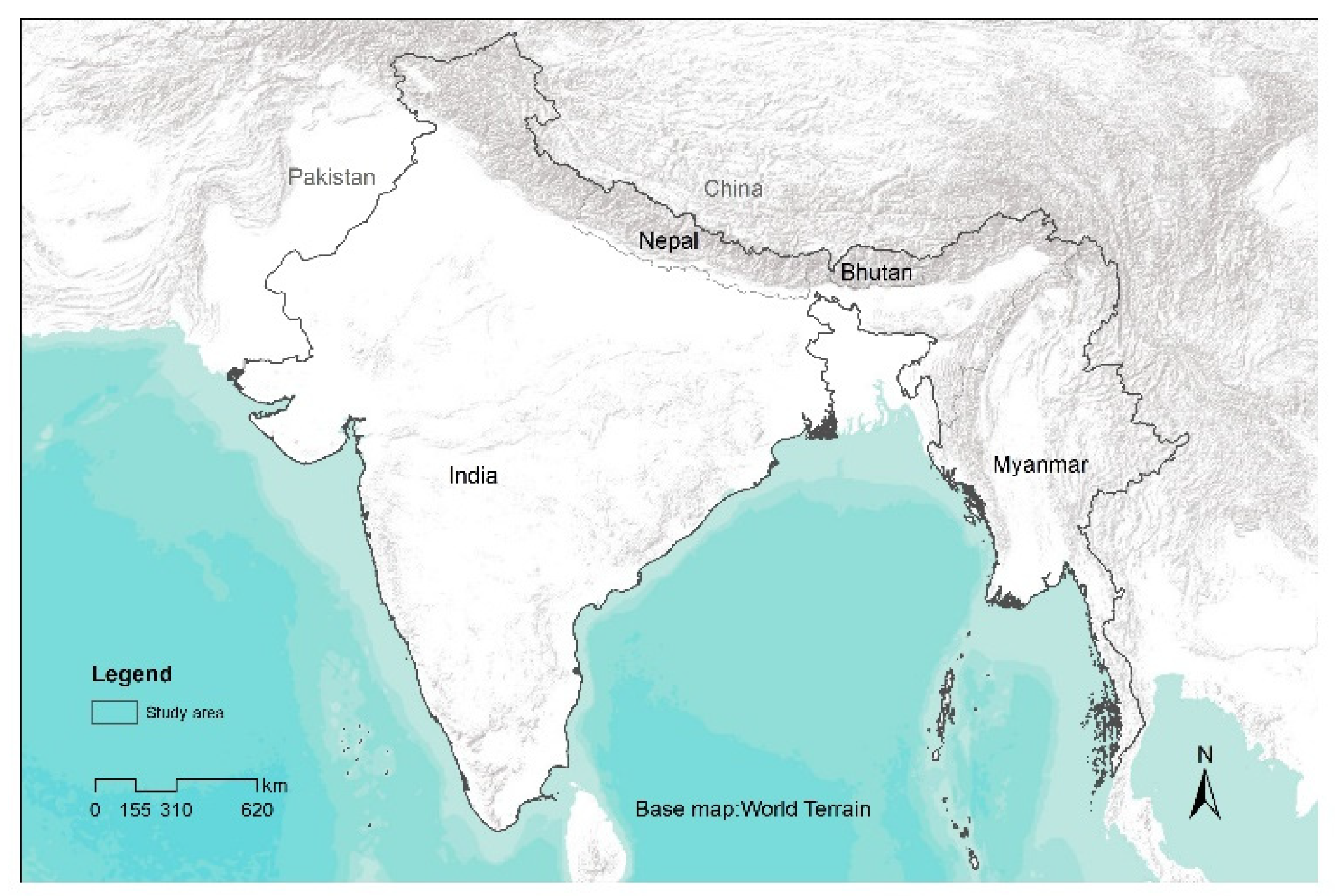

1.1. A Brief Illustration of REDD+ in Bhutan, India, Myanmar, and Nepal

1.1.1. REDD+ in Bhutan

1.1.2. REDD+ in India

1.1.3. REDD+ in Myanmar

1.1.4. REDD+ in Nepal

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

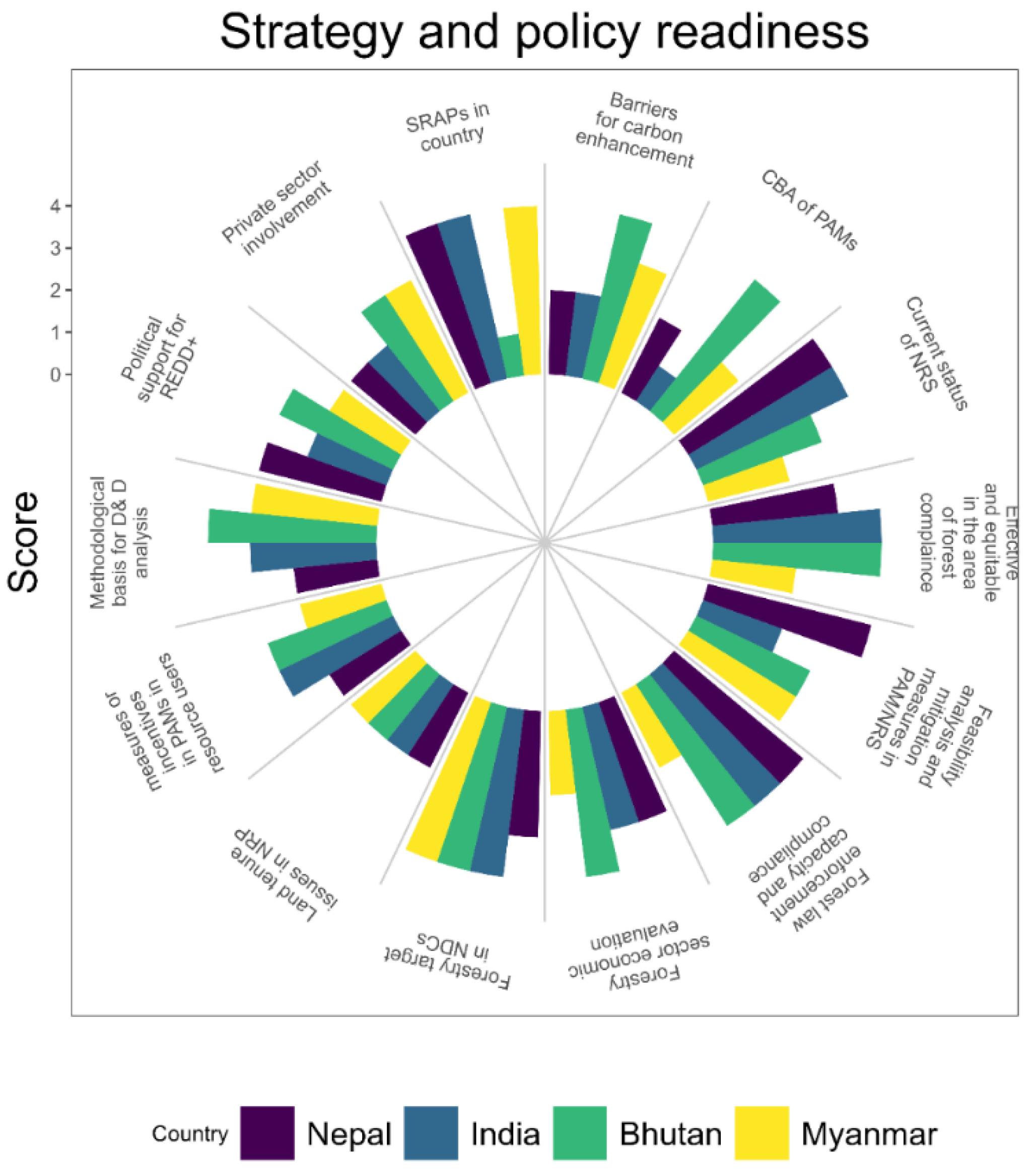

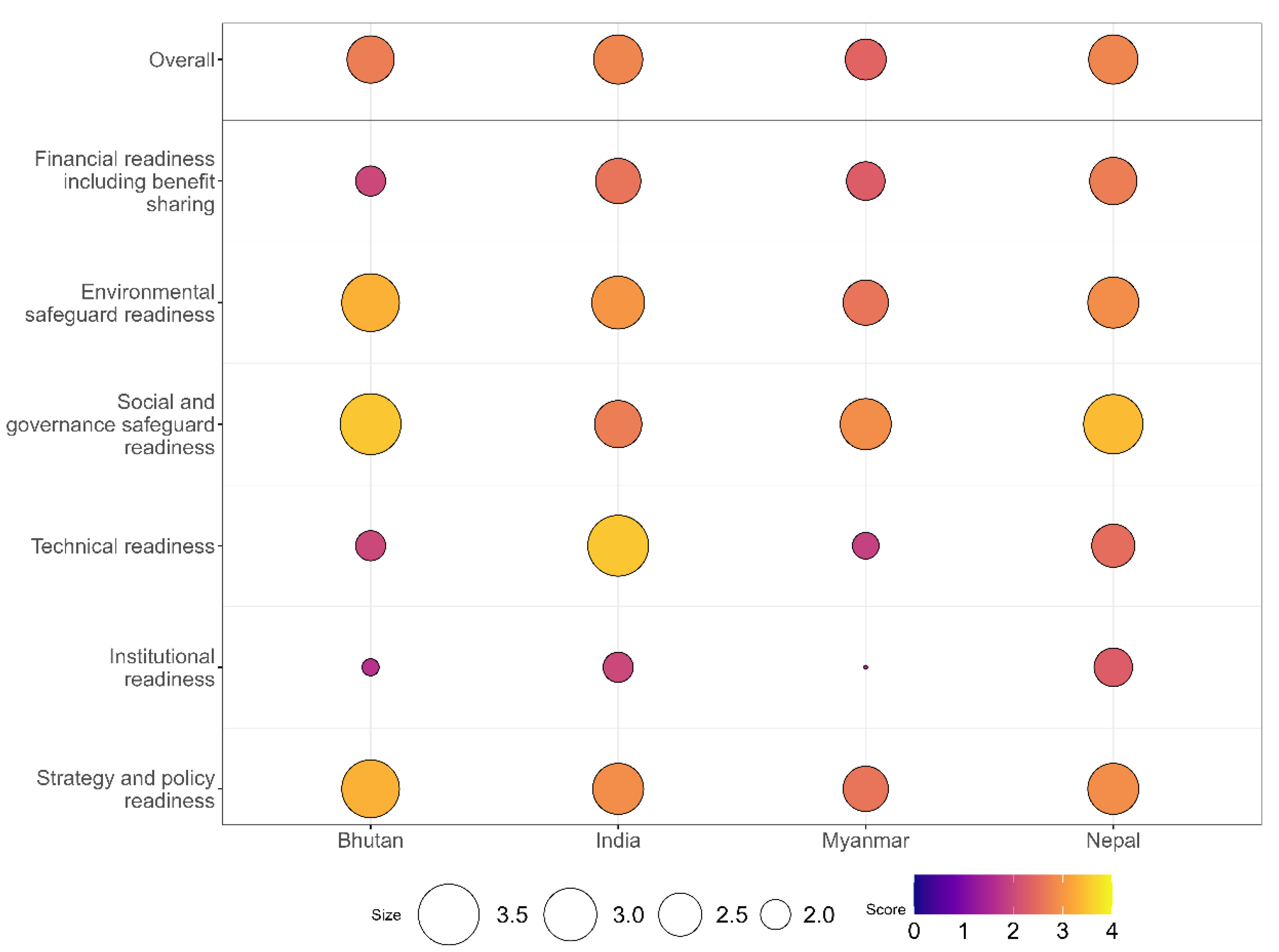

3.1. Strategy Readiness

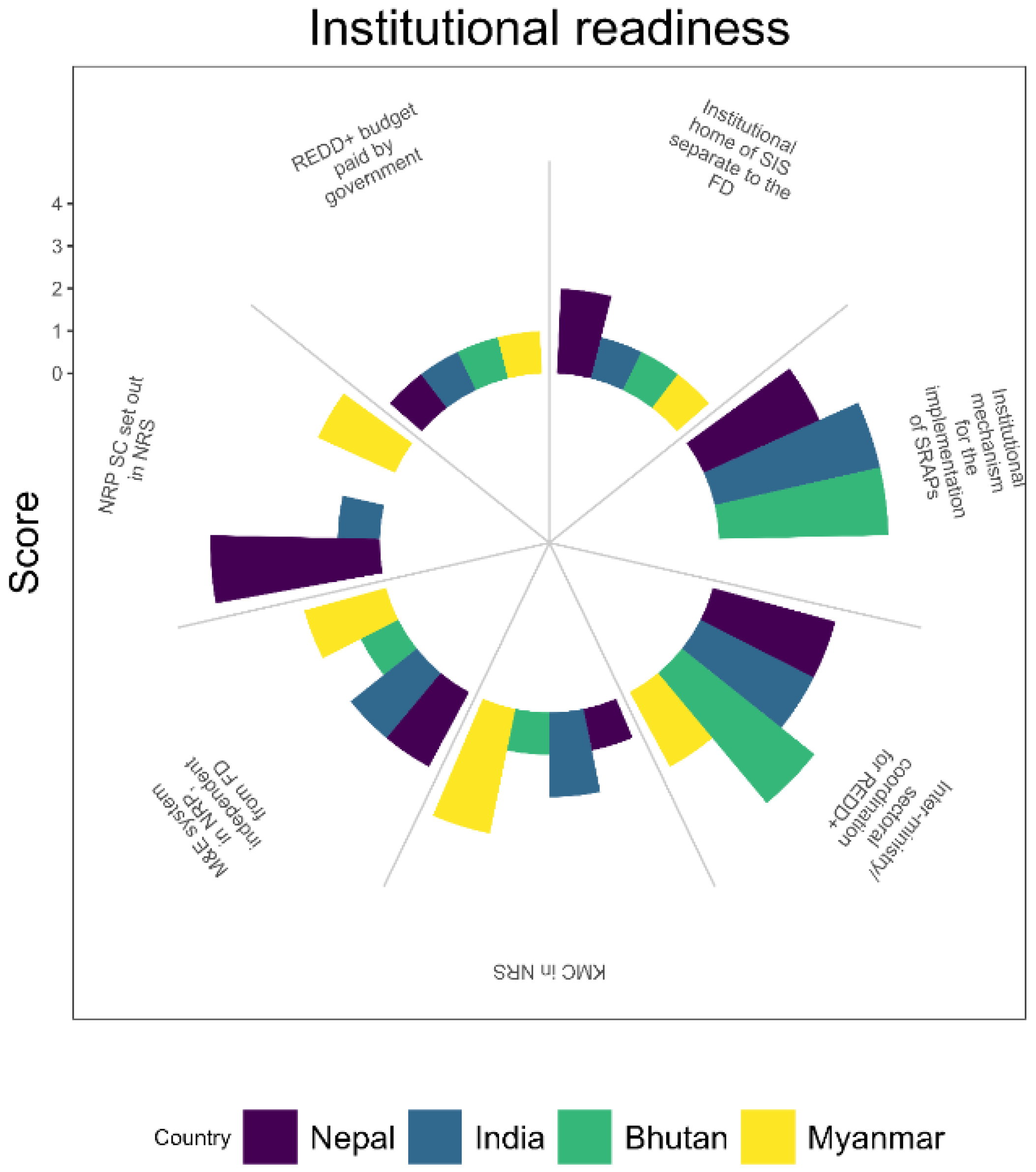

3.2. Institutional Readiness

3.3. Technical Readiness

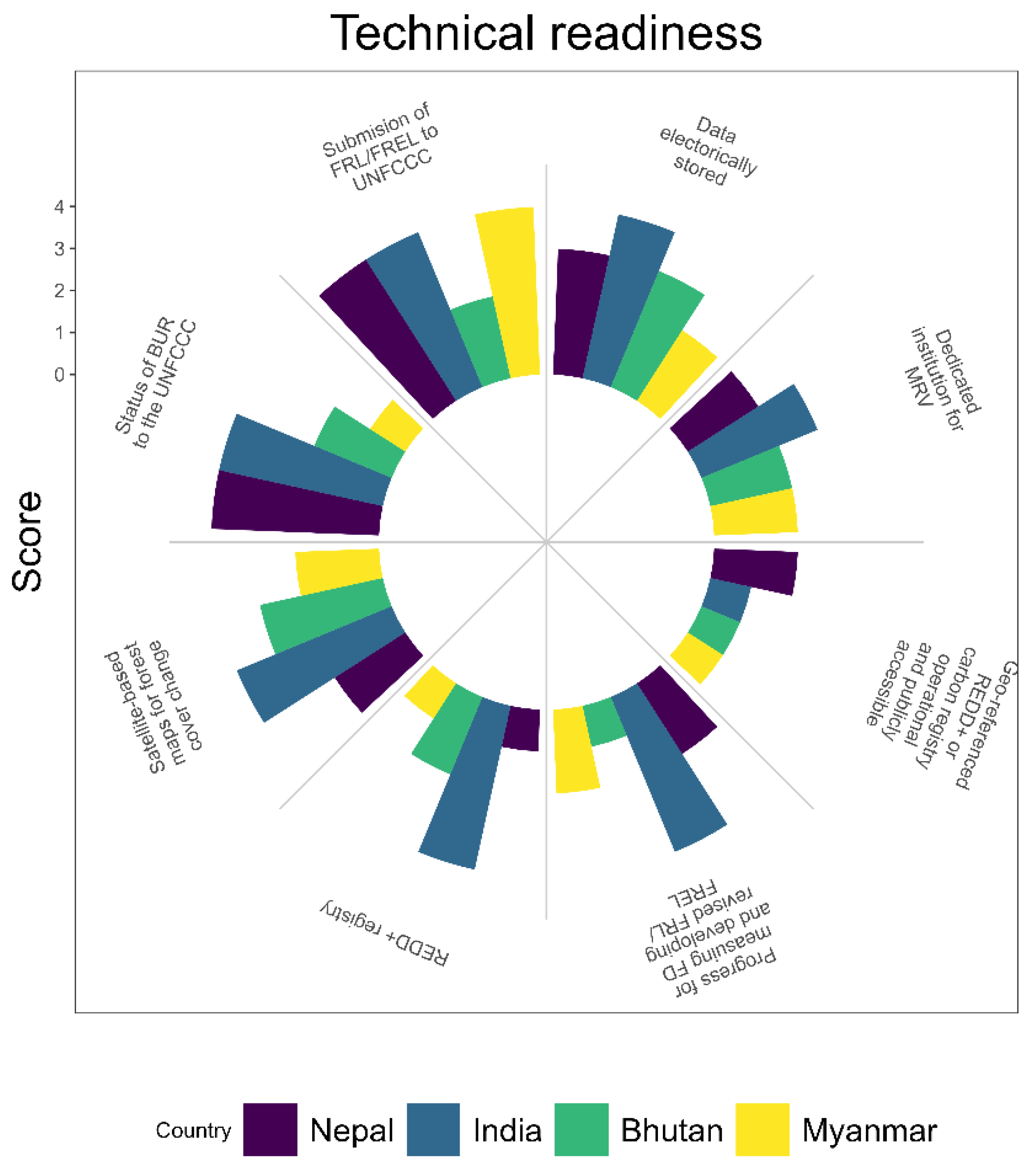

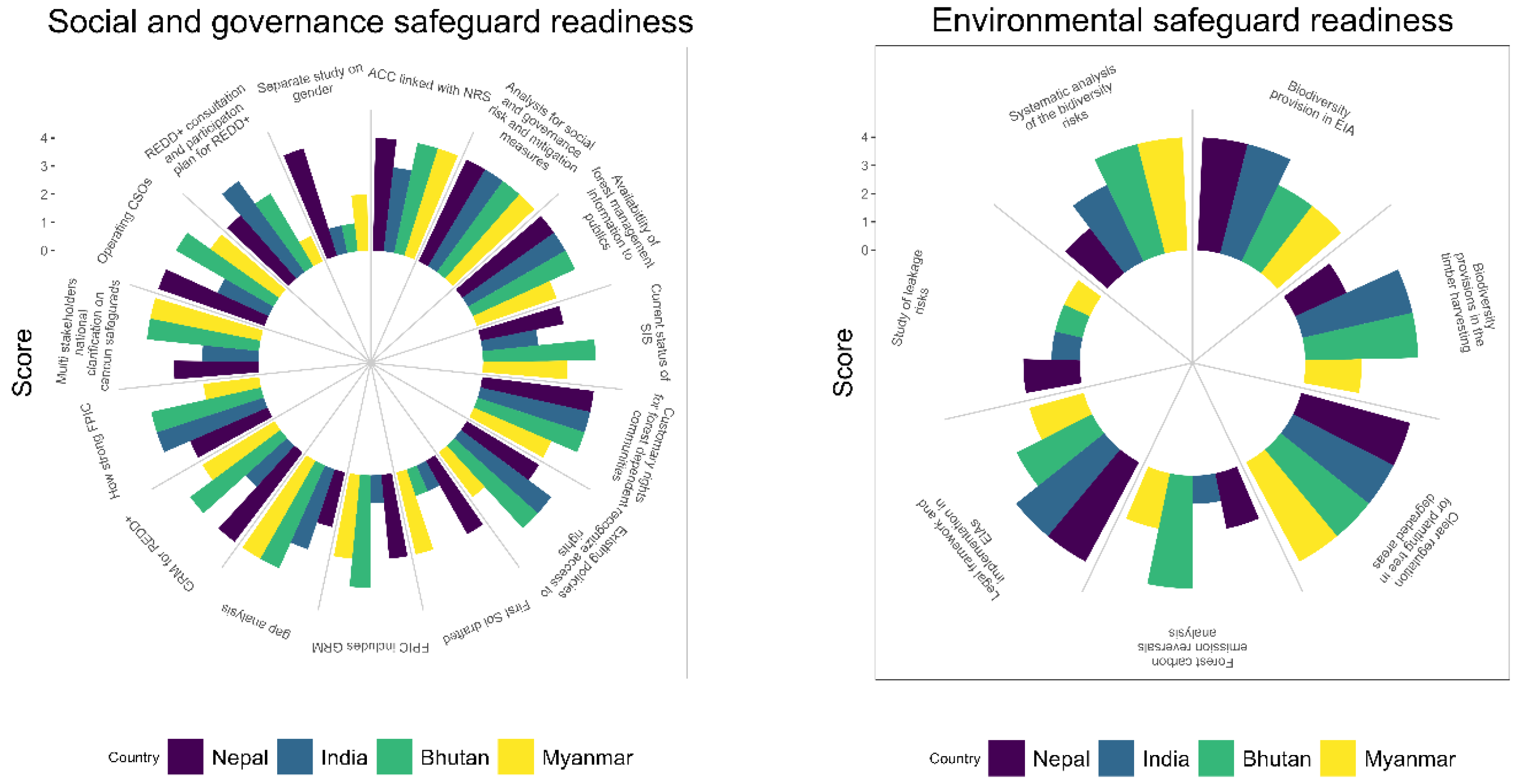

3.4. Safeguard Readiness

3.5. Financial Readiness

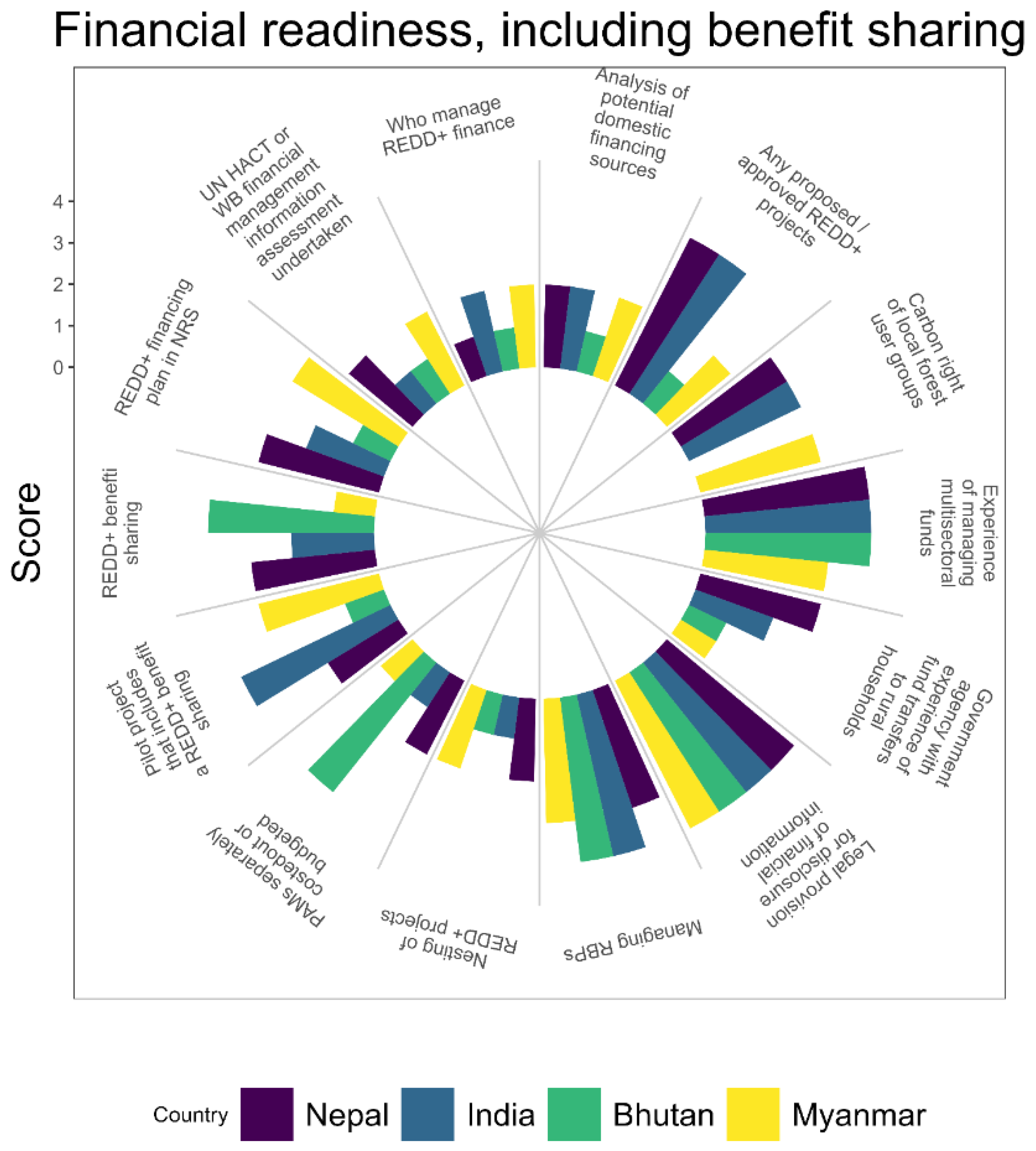

3.6. Capacity Building Needs

3.7. Overall Readiness

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duchelle, A.E.; Simonet, G.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Wunder, S. What Is REDD+ Achieving on the Ground? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 32, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, T.; Maraseni, T.; Ma, H.O.; Lopez-Casero, F. Five Years of REDD+ Governance: The Use of Market Mechanisms as a Response to Anthropogenic Climate Change. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 79, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio, M.E. The Warsaw Framework and the Future of REDD+. Yearb. Int. Environ. Law 2013, 24, 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.J.; Penman, J. An Overview of REDD+. Unasylva 2016, 67, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. In Proceedings of the South-South Learning Workshop on “Forest Reference level (FRL) Assessment Process in Asia and the Pacific” REDD+ Process and Finance Possibilities, Pokhara, Nepal, 10–11 April 2017.

- Karki, R.; Paudel, N.S.; Adhikary, A.; Manandhar, S. Comparing and Contrasting National REDD + Strategies in the Hindukush Himalayan Region: Implications for REDD + Implementation. J. For. Livelihood 2018, 17, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- MoFE Nepal National REDD+ Strategy (2018–2022) 2018. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/system/files/documents/Nepal%20National%20REDD%2B%20Strategy.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- MoEFCC. National Redd+ Strategy, India; MoEFCC: New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, B.; Herold, M.; De Sy, V.; Wijaya, A.; Verchot, L.; Penman, J. Capacity Development in National Forest Monitoring; CIFOR: West Java, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Romijn, E.; Lantican, C.B.; Herold, M.; Lindquist, E.; Ochieng, R.; Wijaya, A.; Murdiyarso, D.; Verchot, L. Assessing Change in National Forest Monitoring Capacities of 99 Tropical Countries. For. Ecol. Manage. 2015, 352, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FCPF Forest Reference Emission Levels. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/forest-reference-emission-levels (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Menton, M.; Ferguson, C.; Leimu-Brown, R.; Leonard, S.; Brockhaus, M.; Duchelle, A.E.; Martius, C. Further Guidance for REDD+ Safeguard Information Systems?: An Analysis of Positions in the UNFCCC Negotiations; CIFOR: West Java, Indonesia, 2014; Volume 99. [Google Scholar]

- FRMD. National Forest Inventory Report: Stocktaking Nations Forest Resources; FRMD: London, UK, 2016; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Results-Based Finance for REDD-plus -Lessons Learned from the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility and the BioCarbon Fund; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- DoFPS. Action Plan for Bhutan’s National Forest Monitoring System for REDD+ under the UNFCCC; DoFPS: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amatya, S.; Yangden, K.; Wangdi, D.; Phuntsho, Y.; Dorji, L. National Forest Inventory of Bhutan: Shift in Role from Traditional Forestry to Diverse Contemporary Global Requirements WHY IS NATIONAL FOREST. J. For. Livelihood 2018, 17, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- FRMD. National Forest Inventory Report: Stocktaking Nation’s Forest Resources, Volume II; FRMD: Bhutan, South Asia, 2018; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, A. Understanding Forests beyond Forest Cover: Bhutan’s REDD+ Journey. Available online: https://www.un-redd.org/post/2019/08/22/understanding-forests-beyond-forest-cover-bhutan-s-redd-journey (accessed on 13 May 2019).

- UNFCCC. UNFCCC Sites and Platforms: The Paris Agreement. Available online: http://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/%0Aconvention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf%0A (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- USAID. Managing India’s Forests in a Changing Climate: Emerging Concepts and Their Operationalization; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, N.; Verma, N.; Windhorst, K.; Phuntsho, Y.; Rawat, R.S. Forest Landscape Restoration in Hindu Kush Himalaya through REDD+ Mechanism-Synergies in Policy Formulation and Implementation. In REDD+ Readiness in Hindu Kush Himalaya; Rawat, R.S., Karky, B.S., Rawat, V.R.S., Bhattarai, N., Windhorst, K., Eds.; Biodiversity and Climate Change Division Directorate of International Cooperation Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education P.O. New Forest: Dehradun, India, 2020; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. REDD+ Web Platform. Available online: https://redd.unfccc.int/submissions.html?country=mm (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- ICFRE. Uttarakhand State REDD + Action Plan; ICFRE: Dehradun, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ICFRE. Mizoram State REDD + Action Plan; Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ICFRE. Himachal Pradesh State REDD+ Action Plan; ICFRE: Dehradun, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ICFRE. Sikkim State REDD+ Action Plan; ICFRE: Dehradun, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MoEFCC. National Working Plan Code 2014; MoEFCC: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Borah, B.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Ishwar, N. Bonn Challenge and India; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9782831719122. [Google Scholar]

- UN-REDD. Myanmar REDD+ Readiness Roadmap; UN-REDD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- MONREC. Forest Reference Level (FRL) of Myanmar; MONREC: Naypyidaw, Myanmar, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FRI. Shan State REDD+ Action Plan, Myanmar; FRI: Naypyidaw, Myanmar, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MONREC; UN-REDD. Myanmar’s National Approach to REDD+ Safeguards; MONREC: Naypyidaw, Myanmar; UN-REDD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dhungana, S.; Poudel, M.; Bhandari, T.S. REDD+ in Nepal: Experiences from REDD Readiness Phase; Dhungana, S., Poudel, M., Bhandari, T.S., Eds.; REDD Implementation Centre, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Government of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, J.; Windhorst, K.; Poudel, M.; Bhattarai, N. Subnational Capacities Strengthened by REDD + Himalaya Project in the Districts of Nepal. J. For. Livelihood 2018, 17, 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, B.S.; Adhikari, S.; Khanal, Y.; Koirala, P.N.; Phuyal, S.P. A Decade of REDD+ Programme in Nepal. In REDD+ Readiness in Hindu Kush Himalaya; Rawat, R.S., Karky, B.S., Rawat, V.R., Bhattarai, N., Windhorst, K., Eds.; Biodiversity and Climate Change Division Directorate of International Cooperation Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education P.O. New Forest: Dehradun, India, 2020; pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rawat, R.S.; Karky, B.S.; Rawat, V.R.; Bhattarai, N.; Windhorst, K. REDD+ Readiness in the Hindu Kush Himalaya; Biodiversity and Climate Change Division Directorate of International Cooperation Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education P.O. New Forest: Dehradun, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MoFSC. National Forest Reference Level of Nepal (2000–2010); MoFSC: Nepal, 2016; pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Minang, P.A.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Duguma, L.A.; Alemagi, D.; Do, T.H.; Bernard, F.; Agung, P.; Robiglio, V.; Catacutan, D.; Suyanto, S.; et al. REDD+ Readiness Progress across Countries: Time for Reconsideration. Clim. Policy 2014, 14, 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casse, T.; Milhøj, A.; Nielsen, M.R.; Meilby, H.; Rochmayanto, Y. Lost in Implementation? REDD+ Country Readiness Experiences in Indonesia and Vietnam. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Herold, M.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Verchot, L. V REDD+ Readiness: Early Insights on Monitoring, Reporting and Verification Systems of Project Developers. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 34038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, D.; Gaugris, J.; Mollicone, D.; Scriven, J.; Corblin, A.; Ndikumagenge, C.; Aquino, A.; Crete, P.; Sanz-Sanchez, M.-J. Financing and Current Capacity for REDD+ Readiness and Monitoring, Measurement, Reporting and Verification in the Congo Basin. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westholm, L. Getting Ready for REDD+. Focali Rep. 2010, 2010, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D. Safeguards and Multiple Benefits in a REDD+ Mechanism; Canadian Electronic Library: Canada; Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1214091/safeguards-and-multiple-benefits-in-a-redd-mechanism/1767194/ (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Johns, T.; Johnson, E.; Greenglass, N. An Overview of Readiness for REDD: A Compilation of Readiness Activities Prepared on Behalf of the Forum on Readiness for REDD; 149 Woods Hole Road: Falmouth, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UN-REDD. REDD+ Academy: Learning Journal; UN-REDD Programme Secretariat; International Environment House: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-807-3647-2. [Google Scholar]

- FCPF. A Guide to the FCPF Readiness Assessment Framework; FCPF: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, J.S.; Allendorf, T.; Radeloff, V.; Brooks, J. Effects of National Forest-Management Regimes on Unprotected Forests of the Himalaya. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of India National Foresty Policy 1988, 10. Available online: https://mpforest.gov.in/img/files/Policy_NFP.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Joshi, A.K.; Pant, P.; Kumar, P.; Giriraj, A.; Joshi, P.K. National Forest Policy in India: Critique of Targets and Implementation. Small-Scale For. 2011, 10, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, T.N.; Hlaing, E.E.S.; Aye, Y.Y.; Chan, N.; Maung, N.L.; Phyoe, S.S.; Thu, P.; Pham, T.T.; Maharani, C.; Moeliono, M.; et al. The Context of REDD+ in Myanmar: Drivers, Agents and Institutions; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2020; Volume 202. [Google Scholar]

- Banikoi, H.; Karky, B.S.; Shrestha, A.J.; Aye, Z.M.; Oo, T.N.; Bhattarai, N. Promoting REDD+ Compatible Timber Value Chains: The Teak Value Chain in Myanmar and Its Compatibility with REDD+; ICIMOD: Lalitpur, Nepal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger, G.; San, P.P.; Arnold, F.; Mon, M.S.; Min, N.E.E. Background Report for Identifying the Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Myanmar; UN-REDD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, K. Commercial Agriculture Expansion in Myanmar: Links to Deforestation, Conversion Timber, and Land Conflicts. For. Trends 2015, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- South, A. Towards “Emergent Federalism” in Post-Coup Myanmar. Contemp. Southeast Asia 2021, 43, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Sarmiento Barletti, J.P.; Ravikumar, A.; Korhonen-Kurki, K. Multi-Level Governance: Some Coordination Problems Cannot Be Solved through Coordination; CIFOR: West Java, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nguon, P.; Neak, C.; Maung, T.M.; Han, P.P.; Onprom, S.; Boyle, T.; Scriven, J. Development of National REDD+ Strategy in Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand. Dev. Clim. Chang. Mekong Reg. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, D.; Scriven, J.; Jonckheere, I.; Laughlin, J.; Todd, K. Toward REDD+ Implementation. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoh, J.; Oduro, K.A.; Park, J.; Lee, Y. Towards REDD+ Implementation: Deforestation and Forest Degradation Drivers, REDD+ Financing, and Readiness Activities in Participant Countries. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FCPF. Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/country/nepal (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- GoN. Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Report; GoN: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- GCF. Accelerating REDD+ Implementation; GCF: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, M. The Curious Case of India’s Missing Forest Policy. Mongabay 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zaw, T.N.; Lim, S. The Military’s Role in Disaster Management and Response during the 2015 Myanmar Floods: A Social Network Approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 25, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J.D.; Tacconi, L.; Irawan, S.; Wijaya, A.H. Village Transfers for the Environment: Lessons from Community-Based Development Programs and the Village Fund. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 108, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, S.; Murthy, I.K.; Kadaverugu, R.; Dasgupta, R.; Kumar, M.; Adesh Gadpayle, K. Agroforestry to Achieve Global Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Targets: Are South Asian Countries Sufficiently Prepared? Forests 2021, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Readiness Category | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Strategy readiness/policy readiness | National REDD+ Strategy (NRS) |

| Methodology of D&D drivers’ analysis | |

| Risk/feasibility analysis on PAMs/S&As | |

| Extra-sectoral PAMs/S&As | |

| Cost–benefit analysis of PAMs/S&As | |

| Analysis of barriers to carbon stock enhancement | |

| PAMs/S&As with private sector/supply chain focus | |

| Forest sector economic valuation study | |

| Forestry targets in NDCs * | |

| High-level political support for REDD+ * | |

| Incentives in PAMs/S&As to change ‘business as usual’ * | |

| Forest law enforcement capacity and compliance * | |

| Effective and equitable judicial system * | |

| Institutional readiness | Non-forestry sector leadership of PAMs/S&As |

| Steering Committee: formation and independence | |

| Institutional independence of SIS | |

| M&E: institutional formulation and independence | |

| Communications/knowledge management strategy | |

| MRV institutional arrangements | |

| Management of implementation finance/RBPs | |

| Inter-ministry/sectoral coordination * | |

| Technical readiness | Submission of FRL/FREL to UNFCCC |

| Carbon pools in FRL/FREL | |

| Use of national Emissions Factor (EF) | |

| Forest degradation measurement | |

| National Forest Monitoring System | |

| REDD+/Carbon Registry | |

| Accessibility NFI data | |

| Most recent satellite forest cover map | |

| Biennial Update Report (BUR) | |

| Safeguard readiness | Social and governance risk analysis of PAMs/S&As |

| Safeguards Information System progress | |

| Summary of information | |

| Policies, Laws, and Regulations (PLR) gaps analysis | |

| Safeguards contextualization analysis | |

| Grievance Redress Mechanism (GRM) for REDD+ | |

| Analysis of gender equity impacts of PAMs/S&As | |

| Anti-corruption commission or equivalent | |

| Transparency of forest management data | |

| Biodiversity risks analysis of PAMs/S&As | |

| Regulation of plantation crops on degraded forest land | |

| Biodiversity provisions of timber harvesting regulations | |

| Risk analysis of emission reversals | |

| Rights/tenure of forest-dependent groups/smallholders * | |

| Legal basis and implementation of FPIC * | |

| Legal basis and implementation of EIA * | |

| Biodiversity provisions in EIA regulations * | |

| Financing readiness (including benefit sharing) | REDD+ financing or investment plan |

| Costing/budgeting of PAMs/S&As | |

| Analysis of nesting of REDD+ projects in NRP | |

| REDD+ benefit sharing plan | |

| Experience with demonstration/pilot projects | |

| Experience of cash transfers or RBPs to households | |

| Legal provision for disclosure of financial information | |

| Analysis of domestic financing sources | |

| Approved finance for REDD+ implementation | |

| Confidence in management of RBPs * |

| Readiness Area | Bhutan | India | Myanmar | Nepal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Valuation/green accounts Policy/legal | Ecosystem Valuation CBA of PAMs | Implementing PAMs Integrating social/env. factors in land use planning | Studies of emissions from drivers |

| Institutional | Information management Communications | Communications /knowledge management | Knowledge/comms. methods Capacity building of local stakeholders | Institutional continuity with forest management regimes |

| Technical | NFI database system Uncertainty analysis Inter carb. pool transfers Statistics/data analysis | Registry | Measuring degradation (FRL) Registry | Registry Aligning MRV to international system NFIS |

| Safeguards | EIA | Gender mainstreaming, environmental SIS | GRM, including awareness Risk assessment of reversals and leakage | Stakeholder capacities to implement safeguards Safeguard audit and information systems |

| Finance | Proposal writing | Finance mechanisms (benefit sharing) Nested projects | Benefit sharing system | Fund management—ERP Benefit sharing system |

| Subnational REDD+ | Planning/implementing SRAPs, SIS, including capacity building | Drivers and barriers’ analysis Implementing PAMs | Awareness of SIS/ESMF Identification of safeguard measures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhattarai, N.; Karky, B.S.; Avtar, R.; Thapa, R.B.; Watanabe, T. Are Countries Ready for REDD+ Payments? REDD+ Readiness in Bhutan, India, Myanmar, and Nepal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076078

Bhattarai N, Karky BS, Avtar R, Thapa RB, Watanabe T. Are Countries Ready for REDD+ Payments? REDD+ Readiness in Bhutan, India, Myanmar, and Nepal. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):6078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076078

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhattarai, Nabin, Bhaskar Singh Karky, Ram Avtar, Rajesh Bahadur Thapa, and Teiji Watanabe. 2023. "Are Countries Ready for REDD+ Payments? REDD+ Readiness in Bhutan, India, Myanmar, and Nepal" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 6078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076078

APA StyleBhattarai, N., Karky, B. S., Avtar, R., Thapa, R. B., & Watanabe, T. (2023). Are Countries Ready for REDD+ Payments? REDD+ Readiness in Bhutan, India, Myanmar, and Nepal. Sustainability, 15(7), 6078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076078