Abstract

The interconnected global trading system has proved to be both vulnerable and resistant to crises, despite its asymmetries. The global trading system is constantly changing under the influence of such factors as the digitalization of economic processes and the growing number of nontariff measures to regulate trade volumes, including trade protection measures introduced by countries in order to ensure national economic interests etc. This article analyzes the impact of the tariff and nontariff instruments of export and import regulation on the asymmetries of the global trading system across countries and separate customs territories, depending on their presence in geographical regions or groups of countries associated with different levels of economic development. In order to quantify the possible asymmetries in the global trading system, analysis of variance and regression analysis are applied to explain the variance in the volume of global trade. The regression models for the dependence of export volumes on a number of trade indicators are fitted for developed, developing, and least-developed countries alongside the global trading system as a whole. The research showed that asymmetries of the global trading system exist on the global, regional and bilateral levels. In this research, two types of asymmetries are discussed: asymmetry directly and indirectly linked to international trade processes. To ensure economic development, the global trading system must be modernized so as to reduce the asymmetry. Accordingly, in order to increase effectiveness of the World Trade Organization, suggestions are proposed in regards to reconsidering trade-dispute settling, improving the monitoring of members’ obligations, increasing negotiation process efficiency and defining criteria for categorizing members according to their economic development.

1. Introduction

Permanent aggravation of economic fragility, an increase in inequality in society, exacerbation of ecological problems, rise of political uncertainty and geopolitical tension raise the risks of crises of different natures around the world. As a rule, these risks are considered separately; however, they can interact and create cascade risks and disturbances to the environment, the economy and society, as well as cause a great number of social and ecological problems and considerable economic losses. Healthcare and economic crises caused by the pandemic have become major stress tests for the global trading system, causing unprecedented shocks to global supply chains and trade relations between countries. Nevertheless, the global trading system has proven to be steady. The global trading system has been, and continues to be, a source of flexibility and diversification and a major mechanism during the pandemic and other crises, helping countries to cope with them by simplifying access to vital goods and foods and supporting their economic recoveries. The interconnected global trading system has appeared to be both vulnerable and resistant to crises, although it has a big number of asymmetries and, as a rule, economic failures on the global scale mostly affect developing countries, particularly least-developed countries rather than developed economies.

Transformation of the trading system is taking place at an accelerated pace due to the comprehensive digitalization of economic processes. In particular, this includes the introduction of paperless trade; the spread of electronic payment systems; the growth of trade in digital products; the globalization of all trade aspects, which, in turn, expands the range of subjects of such a system; the comprehensive liberalization of trade, which coexists with the use of neoprotectionist tools for regulating foreign trade volumes by a number of countries, etc.

Against this background, the number of regional trade agreements concluded by countries and separate customs territories with different levels of economic development from all regions of the world is growing exponentially [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. In such a case, there is not only a deepening of existing asymmetries, but also the emergence of new ones in the global trading system [9,10,11,12,13]. Under the current circumstances, the decline in the effectiveness of the functioning of the World Trade Organization signalizes the need for an urgent response from all system participants to the challenges of the 21st century, with the aim of developing current rules for world trade, taking into account all possible scenarios of the development of the trading system [14,15,16,17].

The transformation of the processes of international trade integration leads to the emergence of new trading systems [18,19,20,21], which can cause economic risks for the functioning of existing ones and changes in the structure of the world trade [22,23].

The interwar experience of beggar-thy-neighbor protectionism and the control over capital that was introduced by governments that sought to stimulate domestic economic activity and employment level has become the genesis of a multilateral trading system [24]. Its further evolution was caused by the introduction of the two trade-policy principles of reciprocity and nondiscrimination, which set a foundation for comprehensive trade liberalization. Implementing these principles let countries overcome historically rooted distrust for each other and make a deal to mutually and beneficially decrease tariff barriers. Mutuality manifested in making equivalent concessions, and it soothed governments’ fears of receiving less-favored regimes from other countries than the one they themselves provided to their trade partners, while nondiscrimination contributed to assuring countries’ governments that they would use the regime along with other rival countries. Neither of the principles became a sudden intellectual invention, as these notions had already been commonly known in international law. However, their implementation in the trading system was quite an innovative decision, which substantially boosted the strengthening of global trade liberalization [25,26].

According to Robert Keohane, currently, multilateralism is considered to be a partnership of all leading countries when making the most important decisions, which are based on commonly accepted norms, rules and principles, which direct and regulate interstate behavior [27]. However, considering modern tendencies, experts and scientists have gradually started using the global trading system as a research object within the concept of system multilateralism. Therefore, according to Christopher Chase-Dunn, Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer, trade globalization refers to the degree to which long-distance goods exchange and global volume increased (or decreased) with regard to goods exchange in national societies [28].

According to experts of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the following can be considered as global trading system components: trade agreements, trade negotiations, regional integration, challenges that arise before developing countries in the international trading system and entrance into the World Trade Organization (WTO) by new members [29].

Using the results from studying approaches to interpret the notion, in the research, the global trading system is defined as a multicomponent and multilateral system of international trade regulation, which is global in its number of members, volume of regulated export, coverage of trade spheres and integrated goal. Three stages of forming such a system have been distinguished: latent, active and modern, with the second one being the most efficient in forming variable rules of international trade in their coverage sphere.

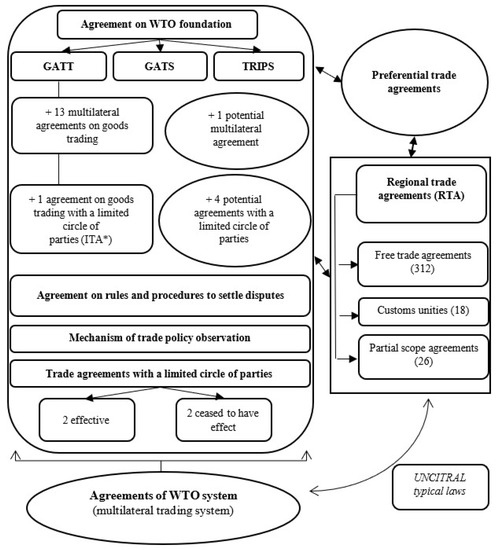

Currently, the system regulatory framework includes 23 multilateral trade agreements, with a limited or unlimited number of parties, 349 effective regional trade agreements, 36 preferential trade agreements, a number of typical UNCITRAL laws, etc.

Based on the foregoing, the objective of the article is to study the impact of the use of tariff and nontariff export and import regulation tools by countries and separate customs territories on the asymmetries of the global trading system, depending on their belonging to a certain geographical region or group of countries with a certain level of economic development.

The object of the study is the transformation process of the global trading system within the conditions of global economic instability. The subject of the study is the asymmetries of the global trading system development, their manifestation, measurements, impacting factors and mechanisms for reaching balance.

In order to reach the set goal, it was vital to solve the following research tasks: the first task was to identify and systematize the existing asymmetries of the global trading system; the second was to investigate the impact of the use of tariff and nontariff tools of export and import regulation by countries and separate customs territories, depending on their belonging to a certain geographical region or group of countries with a certain level of economic development, on the asymmetries of the global trading system; the third, based on the methods of economic and mathematic modeling, was to distinguish the most substantial factors impacting the development of the global trading system; the fourth was to develop recommendations for improving normative and procedure principles of the World Trade Organization’s functioning, corresponding to modern realia.

Within the study, analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the following indices has been carried out: RTA, global export and import of products in 2020, the number of trade disputes within the WTO, general number of nontariff measures regulating trade in countries, as well as the number of tied tariff lines, average tied and PT duty rates and analogous indices for agricultural and nonagricultural products. One-way analysis was carried out for each index using ANOVA and Fisher’s test. Pairwise differences were tested with Tukey’s test, and regression equations for each country group were made.

The major contribution of the article is seen in a complex analysis, distinguishing and mathematically proving and grounding the existence of asymmetries of the global trading system as a subsystem of the global trading economic system, which exist on the global, regional and international levels; the systematization of the asymmetries was conducted by dividing them into two key groups: asymmetries directly linked to international trade processes and asymmetries indirectly linked to international trade processes. It has been grounded in the research that, in order to provide greater economic sustainability of countries and customs territories, the global trading system must be modernized. Accordingly, in order to increase the WTO’s functioning efficiency, some suggestions have been made for reconsidering trade-dispute settling, improving monitoring of members’ obligations, increasing negotiation process efficiency and defining the criteria for categorizing members according to their economic development.

Thus, within the framework of this study, the authors singled out the most important factors influencing the development of the global trading system, based on the methods of economic and mathematical modeling.

This study contains several sections: the introduction, followed by the literature review and hypotheses development and the results. The results are divided into three subsections devoted to studying the following issues: firstly, the theoretical basis and determinants of the asymmetries of the global trading system, in particular investigating the modern features of the global trading system and the asymmetries of the global trading system; secondly, analysis of variance of the influence of independent factors on the volume of global trade, in particular investigating the categorization of countries by the level of economic development and the grouping of countries according to location in a specific region; thirdly, econometric analysis of the influence of selected indicators of foreign trade activity on the volume of global exports. The remaining sections cover the novelty of the study and of the results, the discussion and the conclusions.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

A working hypothesis of the study is the supposition that the global trading system is subject to asymmetry in the development of various natures and the movement of the movement. In order to decrease social pressure, we want to bring that to level ecological dangers, hitches in business and economic losses caused by various shocks, and to secure economic sustainability, it is necessary mainly to level asymmetry influence and reach a balance in the global trading system.

Asymmetry is an objective feature of global economic system processes, which are interconnected and interdependent by their nature. Therefore, it is advisable to inquire into the semantics of the “asymmetry” notion in its general meaning, as well as within the global economic system.

Theoretical bases of emerging and characteristic asymmetries of the global economic system development have become the subject of study of numerous scientists.

The notion of “asymmetry” started to be actively used to refer to the global economic system in 2001; American economists George Akerlof, Michael Spence and Joseph Stiglitz received the Nobel Prize for developing a theory and analyzing markets with asymmetrical information. According to these scientists, asymmetrical information generates issues of unfavorable decision making and aggravates risks [30,31].

Borts, Siebert and Myrdal identified major reasons for the emergence of socioeconomic development asymmetries, which lie in the disproportionate allocation of production factors among world regions, particularly capital, labor, land and technologies [32,33,34].

Moreover, the correlation of notions of “symmetry”, “asymmetry”, “disproportionality”, “disbalance”, etc., have also become a research object for scientists. Thus, Kravchuk has investigated the casual relationship of such terms: equilibrium (symmetry), asymmetry, disbalance, instability and crisis [35]. On this occasion, Stoliarchuk indicated that, unlike disproportionality, asymmetry possesses a system nature that reflects forms of global economic development and is a motive force of social progress, being a tool of both discovering and solving its contradictions through crises [36]. Therefore, versatile approaches to defining the notion of asymmetry by scientists are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Approaches to defining the notion of asymmetry concerning global economic processes.

The presence of asymmetries in the foreign trade interests of countries and separate customs territories may be determined as an objective feature of the global economy. It is primarily explained by the fact that, in having nominally equal opportunities in access to foreign markets of goods and services, countries and separate customs territories form their trade policies differently and define their directions, in particular, within the context of choosing priority trade partners or “focused on” goods, which are planned to be promoted in chosen markets or even choosing tools for regulating volumes of trade flows. The asymmetry of foreign trade interests of countries manifests in their foreign policy, which is realized as either liberal or protectionist. Thus, for instance, Virkovska and Ivashchuk legitimately consider that asymmetry of foreign trade interests of countries is caused by such external and internal factors as the aggravation of disbalances in international trade, the existence of risks of breaching set agreements or multilateral and bilateral commitments made by countries during negotiations, the violation of the integrity of global institutional structures in international trade, the trade expansion of particular countries (including China) and the breaching of principles of strategic partnership of trading system members, etc. [40].

In this study, the asymmetry of the global trading system is considered to be a trading system development state, which is characterized by the violation of balance in the regulation of trade processes on different levels, by the disproportionality of the trade, investment, informational and human flows distribution, as well as by tools employed by system members, considering differences in economic development level.

The issue of the classification of global economic development asymmetries has become the subject of study of Lukianenko and Stoliarchuk. Thus, they distinguish such major groups of symmetries: economic (particularly trade), financial and investment, production, infrastructural, technological, informational, social, cultural and geopolitical. Moreover, in the above-mentioned study, intercivilization, inter-regional and interstate asymmetries are also distinguished according to their levels [43]. At the same time, Kravchuk divides asymmetries into lateral, structural, functional and dynamic in the study “Global Development Divergency: Modern Paradigm of Geo-Financial Dimension Forming” [38].

3. Methods

In order to obtain mathematical rationale for the existence of the asymmetries outlined in the introductory part, analysis of variance was conducted, which allows one to confirm or refute the hypothesis that different average values of indicators (volumes of world exports and imports, average bound rates of customs duties and rates under the most-favored-nation (MFN) regime, both for agricultural and nonagricultural goods; and the number of regional trade agreements, nontariff trade measures the number of trade disputes) can really be explained by the fact that different countries and separate customs territories belong to different groups according to the level of economic development and by the criterion of geographical affiliation.

That is, in general, the results of the analysis of variance will make it possible to talk about the mathematically confirmed existence of asymmetry in the development of the global trading system and will also make it possible to determine directions for its elimination.

For the purposes of the study, 2 indicators were chosen as independent variables (categorical factors):

- group_of_countries—groups of countries by the level of economic development (developed, developing and least-developed countries (LDCs) [44,45,46];

- region—regions of the world (Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe, North America, South America and the Caribbean, the CIS).

The following set of indicators will be used as dependent variables:

- RTAs—number of valid regional trade agreements [47];

- Import—import of goods in 2020, USD million dollars;

- Export—export of goods in 2020, USD million dollars [48];

- Disputes_total—the total number of trade disputes between countries and separate customs territories that were resolved within the framework of the WTO [49];

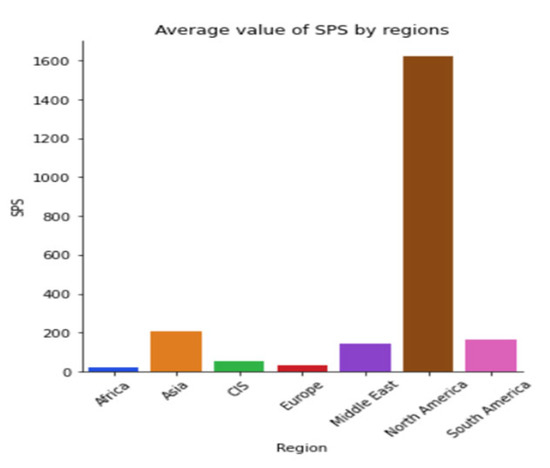

- SPS—number of sanitary and phytosanitary measures imposed by countries [50];

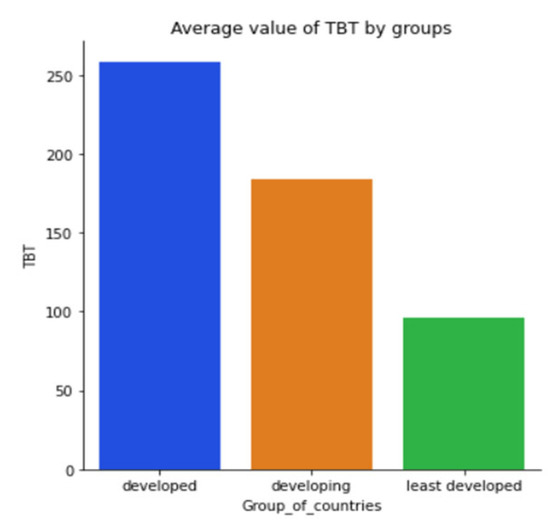

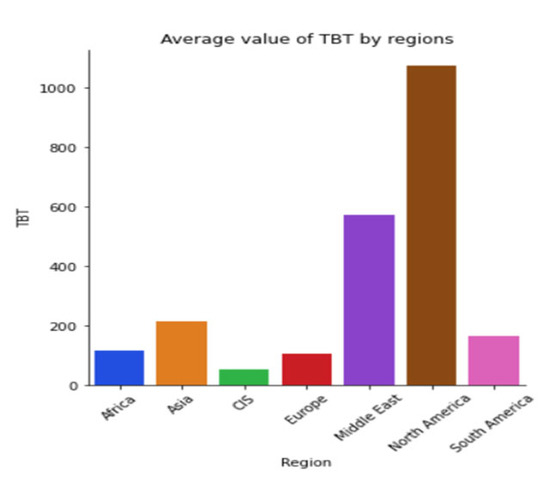

- TBT—number of technical barriers to trade;

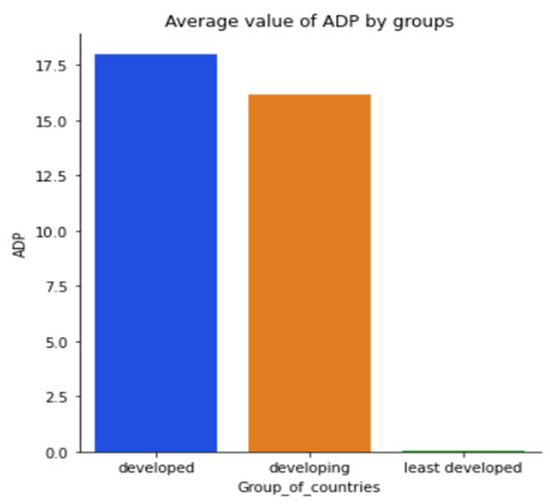

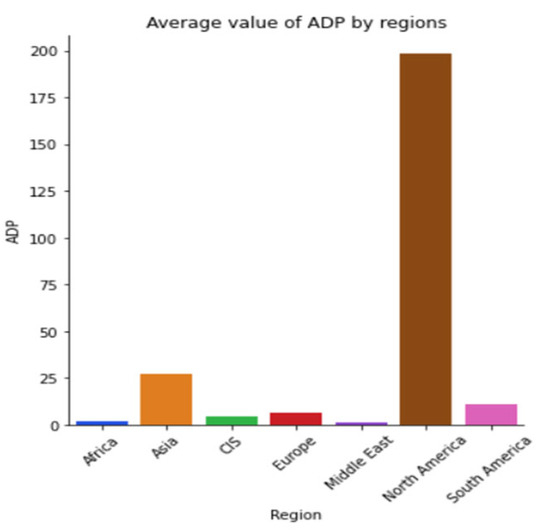

- ADP—number of antidumping measures of countries;

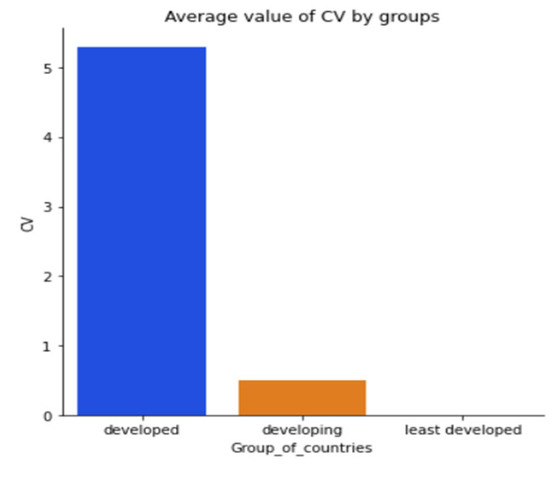

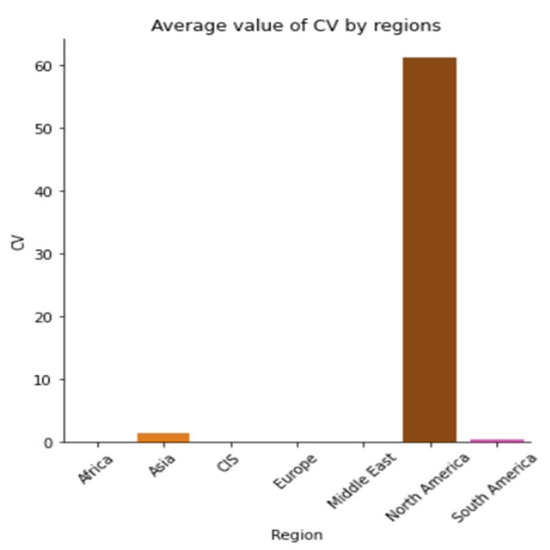

- CV—number of countervailing (compensatory) measures;

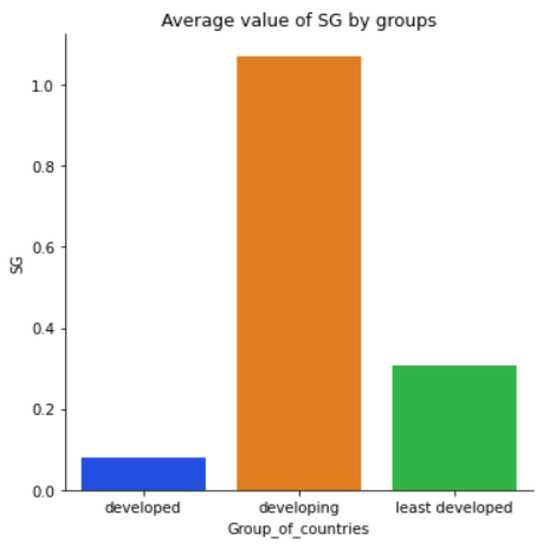

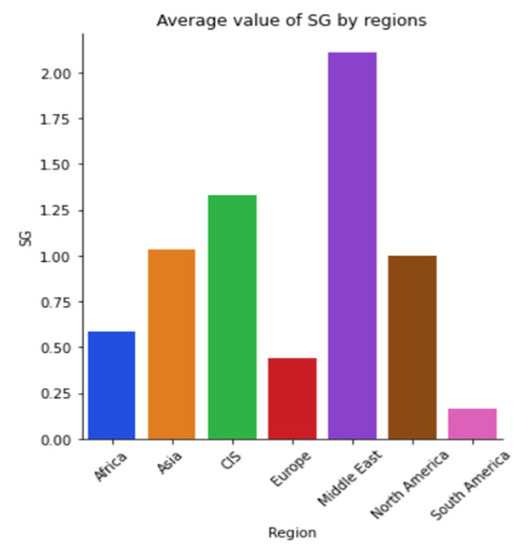

- SG—number of safeguard measures;

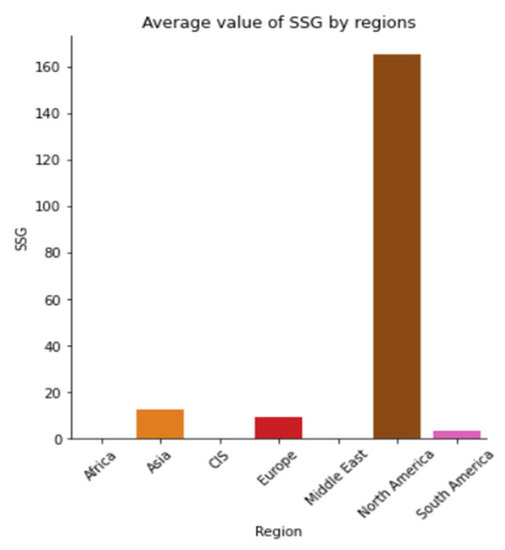

- SSG—number of special safeguard measures;

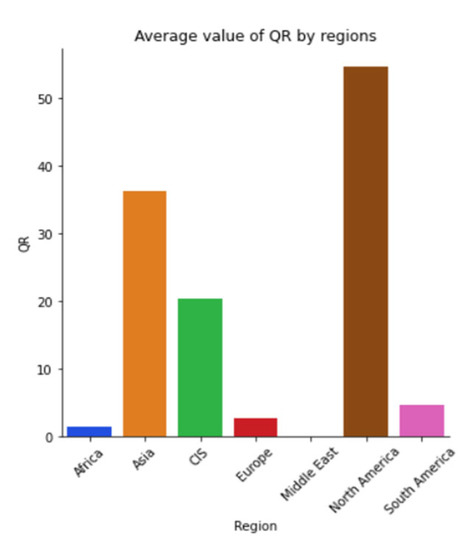

- QR—number of quantitative restrictions introduced by countries;

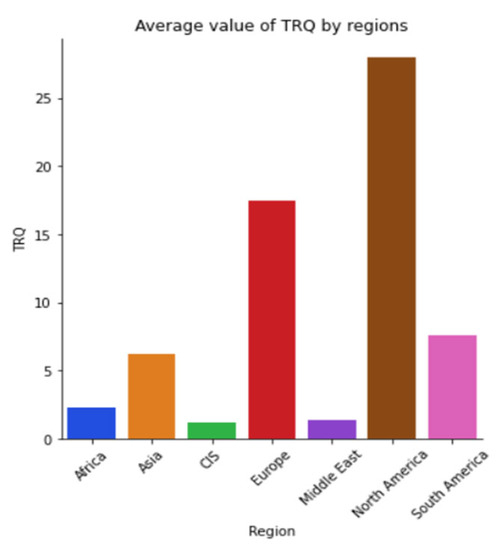

- TRQ—the total number of tariff quotas introduced by WTO members;

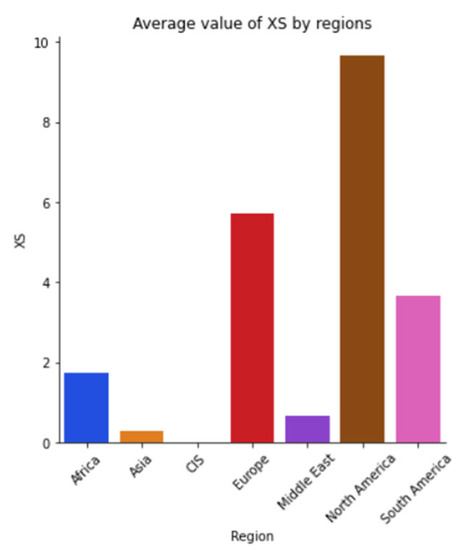

- XS—number of export subsidies;

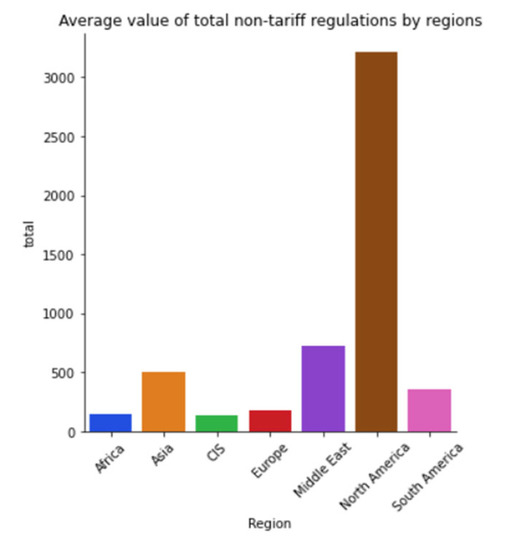

- non_tarif_total—the total number of nontariff measures regulating the country’s trade volumes [51];

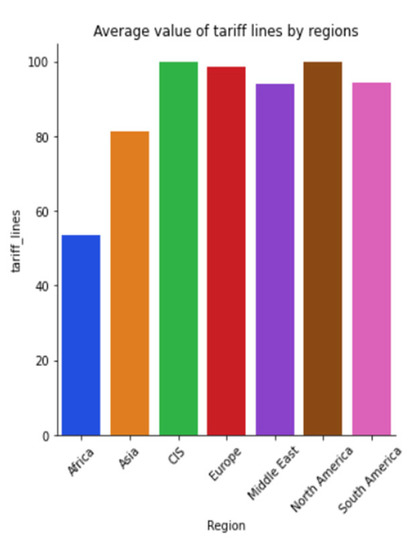

- tariff_lines—the number of binding tariff lines of the WTO member, %;

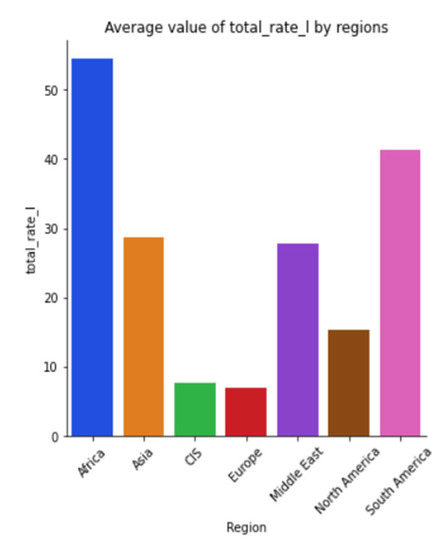

- total_rate_l—average customs duty rate (total, bound), %;

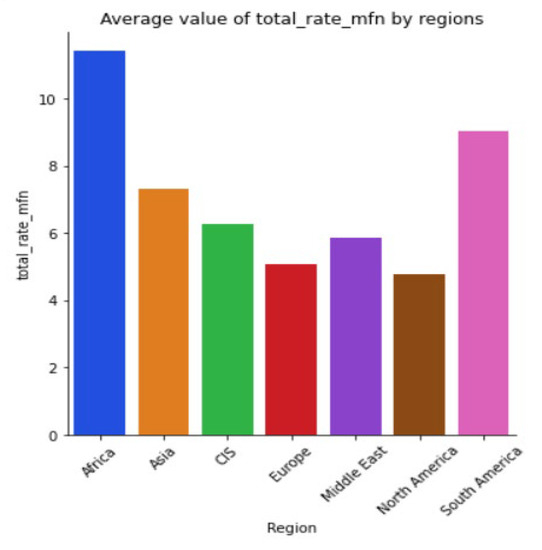

- total_rate_mfn—average customs duty rate (total, most-favored-nation treatment (MFN)), %;

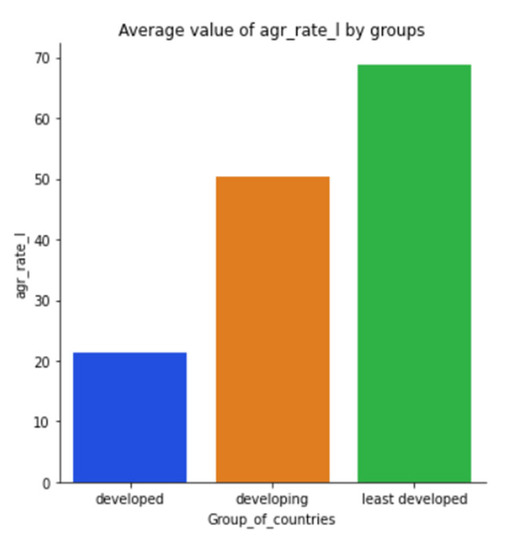

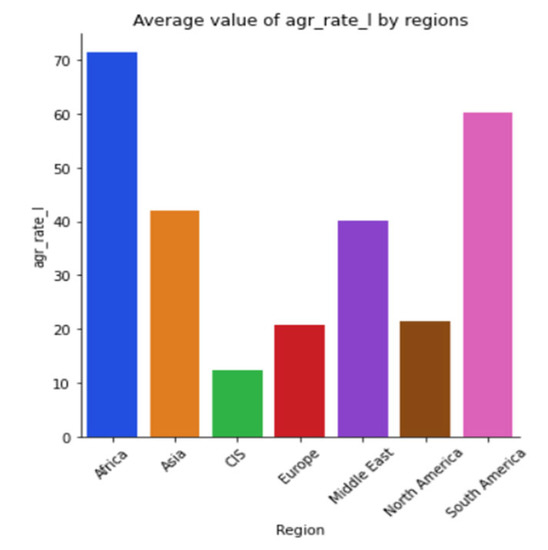

- agr_rate_l—average tariff rate on agricultural goods (bound), % (World Bank 2021) [52];

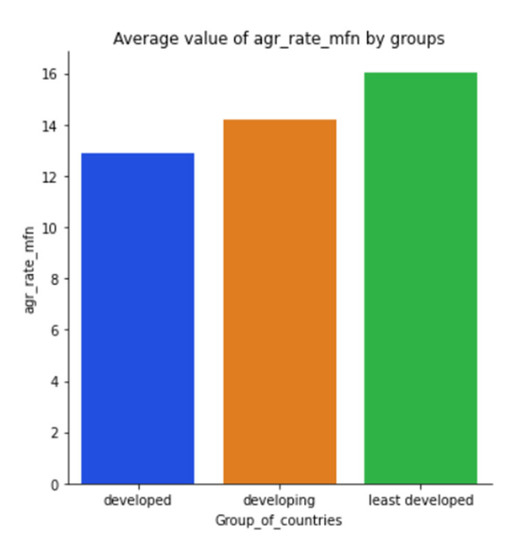

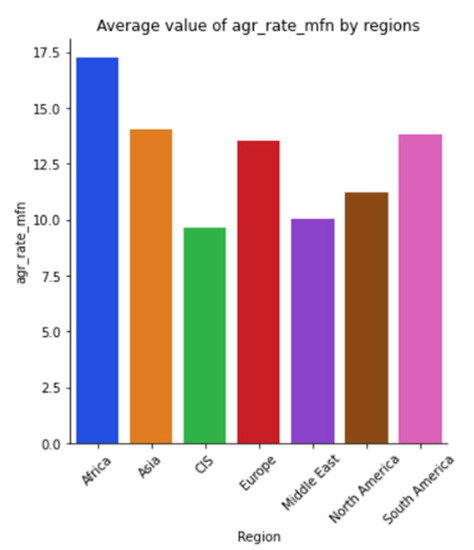

- agr_rate_mfn—average rate of customs duty on agricultural goods (MFN), %;

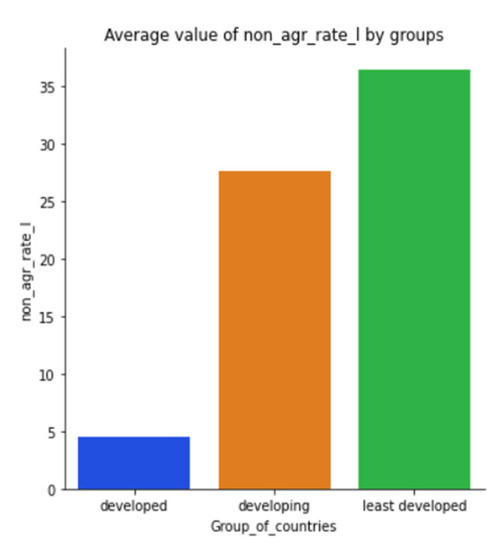

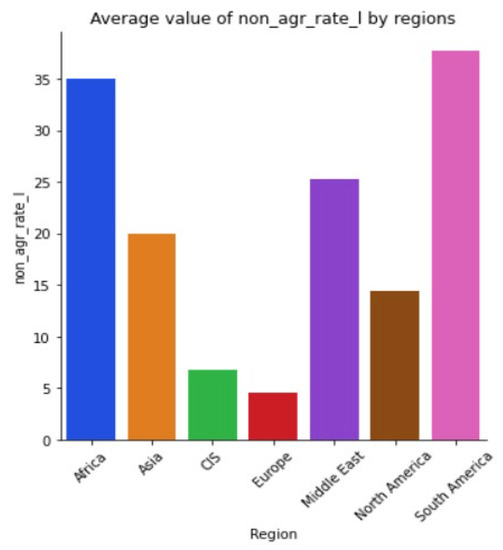

- non_agr_rate_l—average rate of customs duty on nonagricultural goods (bound), %;

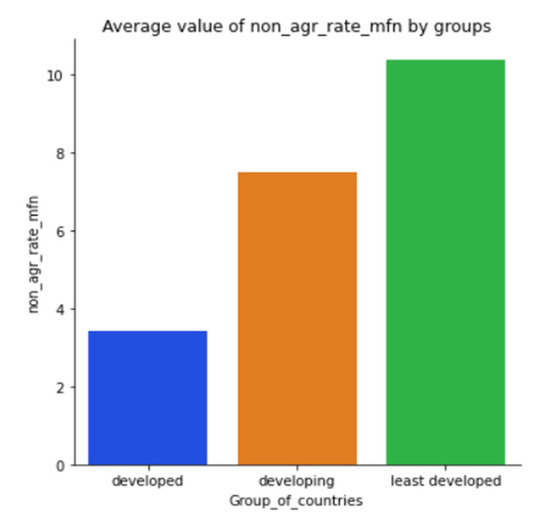

- non_agr_rate_mfn—average rate of customs duty on nonagricultural goods (MFN), %.

In order to study the influence of each independent factor on the dependent variables separately, the one-factor analysis of variance method was used.

Firstly, we propose considering the results of the analysis of variance for the factor group_of_countries—a group of countries by the level of economic development. To do this, the ANOVA is used, which represents the statistical test used to analyze the difference between the average values for more than two groups of indicators. ANOVA determines whether groups formed by different values of a categorical independent variable are statistically different by calculating whether group means differ from the overall mean of the dependent variable. So, for each of the selected indicators, we will put forward two ANOVA hypotheses.

The null hypothesis (H0) of the ANOVA lies in the fact that there is no difference between the group means:

that is, the average value of the selected indicator will not depend on which group by level of development or which region the country belongs to.

H0: μ1 = μ2 = … = μp,

The alternative hypothesis (Ha) is that at least one group is significantly different from the general average value of the variable:

that is, the selected indicator is truly asymmetric, and its average value directly depends on whether a country or a separate customs territory belongs to a group by level of development or a specific region of the world.

Ha: μ1 ≠ μ2 or μ1 ≠ μp or μ2 ≠ μp …,

The ANOVA function uses the F-test (Fisher’s test), which allows for comparing multiple groups at once. The error is calculated for the entire set of comparisons, rather than for each separate two-sided comparison, as would be the case with the t-test (Student’s test). The F-statistic is calculated by the formula:

where MSTR and MSE are intergroup and intragroup variances, respectively. At the same time, the intergroup variance is calculated according to the formula:

and intragroup variance is calculated by the formula:

where is the average value of the indicator X in group i, is the average value of the X indicator, is j-th value of indicator X in group i, is total number of observations, is the number of observations in the group i, and is the number of groups [53].

The null hypothesis (H0) is rejected if the calculated F-statistic is greater than the critical F-statistic (p-value ≤ 0.05). The critical F-statistic is determined by the degrees of freedom and the alpha value.

4. Theoretical Approach to Determinants of the Asymmetries of the Global Trading System

4.1. Modern Features of the Global Trading System

Attempts to start a trade organization gained momentum when the United States additionally proposed it for the UN’s consideration. This proposition led to passing the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) Resolution in February 1946 [46], calling to hold a conference to write the charter of the World Trade Organization. Thus, in 1946, a preparatory committee was created, and it started working on the charter of the future organization. The preparatory committee worked in Geneva till November 1947, but the charter was only completed in 1948 [26]. In 1947, GATT was negotiated, and it immediately gained its validity.

Although GATT was supposed to be added to the organization’s charter, it appeared to be impossible, and even after the charter was finally concluded in Havana in March 1948, it never gained its validity [26]. Therefore, in 1947, GATT was the only existing international document on trade relation issues. It was designed as a multilateral agreement on decreasing tariffs and was supposed to be eventually turned into an international organization.

Cardinal system transformation started from the Uruguay round of multilateral trade talks. In the Declaration Punta-del-Este, countries implicitly recognized the necessity to institutionally reform the GATT system [54]. In April 1990, Canada officially proposed founding the World Trade Organization, which would monitor various legal documents concerning international trade that were developed within the current negotiations [55]. In July 1990, the European community suggested creating effective institutional frames for GATT in order to provide efficient implementation of the Uruguay round results [56]. In 1991, the European community, Canada and Mexico prepared a joint proposal that served as a base for further negotiations, which led to writing a project of the agreement on creating a multilateral trade organization. This agreement was a part of the 1991 Final Act project, which embodied the results of Uruguay round.

The agreement for founding the World Trade Organization was finally signed in Marrakesh, in April 1994, and gained its validity on 1 January 1995. The universal significance of the Marrakesh agreement is stated in point 4 of its preamble, where the members normatively determined the intent “to develop an integrated, more viable and durable multilateral trading system encompassing the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the results of past trade liberalization efforts, and all of the results of the Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations” [57].

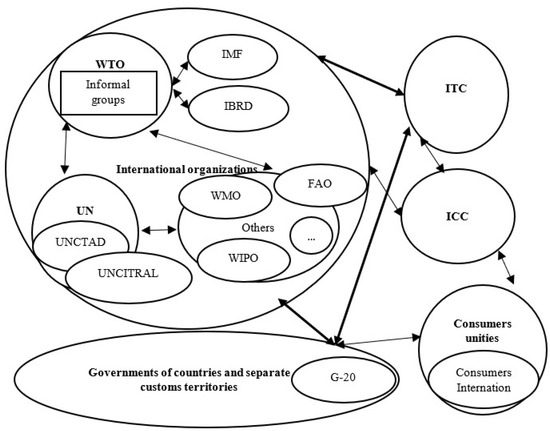

The subject structure of the global trading system has been gradually broadening during its whole transformation period. Moreover, it is featured with both close cooperation among key players and institutions in the trading sphere and continuous contact with other subjects of the global economic system. Therefore, it is reasonable to distinguish such subjects of the global economic system on the current stage of the global trade development (Figure 1), which form tendencies, react against global challenges and determine major vectors of its evolution by their activity.

Figure 1.

Subjects of the global trading system. Source: compiled by the authors on the basis of the own research.

International economic organizations play a major role in the standard regulation of cross-border trade processes and in monitoring compliance with these generally accepted rules.

A central key subject of the global trading system is the World Trade Organization, the only international organization that deals with global trading rules among countries and separate customs territories [58]. As it has been mentioned, the organization in its current state started functioning in 1995, “with a view to raising standards of living, ensuring full employment and a large and steadily growing volume of real income and effective demand, and expanding the production of and trade in goods and services, while allowing for the optimal use of the world’s resources in accordance with the objective of sustainable development, seeking both to protect and preserve the environment and to enhance the means for doing so in a manner consistent with their respective needs and concerns at different levels of economic development” [57].

The agreement for founding the WTO defines five major functions that fully ensure adherence to the principles of the global trading system: nondiscrimination in trade (mutual provision of preferential treatment (PT) in trade and provision of national treatment to goods, services and intellectual property products originating abroad), regulation of trade (mostly by tariff methods), decrease or minimization of the implementation of quantitative and other limiting measures, transparency of trade policies of members and settling trade disputes by consulting, negotiations, etc.

Researching the features of the global trading system, seven key features may be distinguished, particularly hyperglobalization, which lies in the rapid intensification of trade integration, dematerialization of globalization, which highlights the significance of cross-border trade in service sphere, democratic globalization, which means a high level of openness of national markets, cross-globalization, which derives from similarity between North–South trade and investment torrents and torrents with other directions, upturn of a megatrader (China), ultrafast spreading of regional trade agreements and the approaching era of megaregional agreements, as well as a decrease in barriers in product trade under conditions of keeping high barriers in service trade.

Therefore, if the existing global trading system is observed as a system of rules and legal norms that regulate modern cross-border trade processes in multilateral, regional and bilateral dimensions, it will look as follows (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The structure of the global trading system in 2020. * Notes: Information Technology Agreement. Source: compiled by the authors on the basis of their own research.

According to Figure 2, WTO system agreements and regional trade agreements are key components of the system. The legal base of the WTO system contains the agreement for founding the World Trade Organization (Marrakesh Agreement), signed in January 1995, which defines the basic foundations for the organization’s functioning (aims, principles, functions, content, management, etc.) and addenda to it. Among the addenda, so-called “umbrella” agreements are distinguished; they regulate international goods trading (General Agreement on Tarrifs and Trade—GATT [54]), service trading (General Agreement on Trade in Services—GATS [59]) and intellectual property products trading (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights—TRIPS [60]).

There are numerous explanations for why the broadening of the global trade has visually become slower, from short-term cyclic influences such as continuous influence of a financial crisis on the demand level, to more long-term structural changes such as a slow-down of supply chain extensions. At the same time, one argument that has been paid little attention may be distinguished—a rapid transformation of the global trade itself and the inability of the existing system to cope with the modern blurring of trade boundaries. Although the global trading system has proved to be highly successful in opening goods and raw materials trading and thus prompting globalization in the 20th century, it was much less successful in opening markets for trading services and software products or cross-border transfer of data torrents, which are commonly recognized as globalization drivers in the 21st century.

The key idea is that global trade integration has not been completed. On the contrary, vivid signs of the inception of a completely new globalization stage are being seen, as well as the signs that a search of innovative ways to develop and promote global trading cooperation and management in the future, such as in the past, will be a key feature of the diversification of trade development directions, a decrease in poverty level and boost in economic growth [61].

4.2. Asymmetries of the Global Trading System

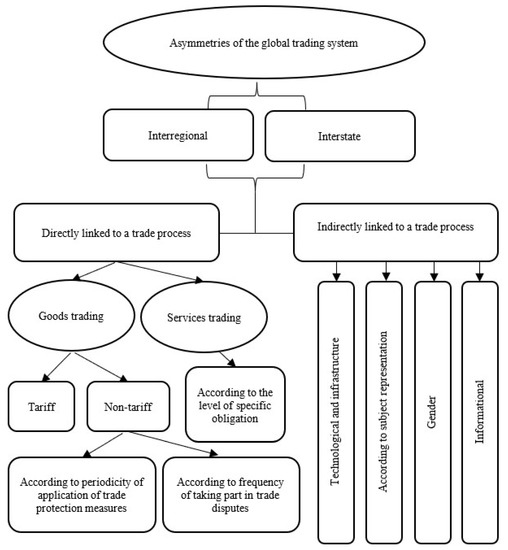

The research results established that asymmetry in trade and tools, which are used to regulate its volume, is observed between countries and separate customs territories that are located in geographically different regions (inter-regional) and groups of countries depending on their economic development (interstate). Moreover, all asymmetries characterized in the study should be divided into two groups—those that are directly linked to the trade process and those that are indirectly linked to some of its aspects. The following types of asymmetries have been distinguished for the sake of the research (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Global trading system asymmetry classification. Source: compiled by the authors on the basis of their own research.

To be precise, in this research, global trading system asymmetries have been analyzed and systematized by being divided into two key groups—asymmetries that are directly linked to international trade processes (asymmetries in goods trading, caused by differences between levels of customs tariffs of countries and the number and variety of implemented nontariff measures of trade volume regulation, including the following trade protection measures: antidumping, compensational and special; in the degree of involvement of countries and separate customs territories in settling trade disputes; asymmetries in service trading that derive from differences between levels of specific commitments of countries to liberalize access to service markets) and asymmetries that are indirectly linked to international trade processes (technological and infrastructural, gender, informational, according to subjectivity and particularly considering the growing role of micro-, small and middle-sized enterprises in the export activity of countries).

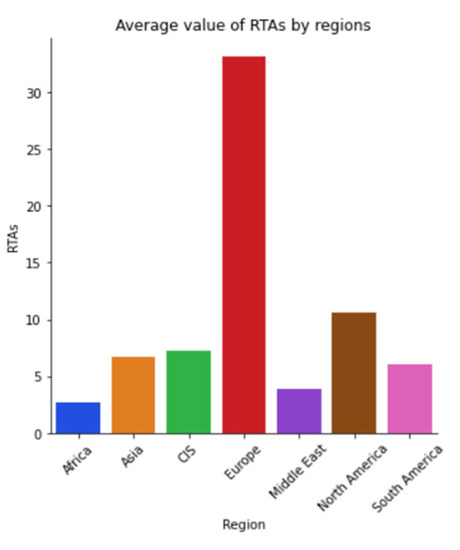

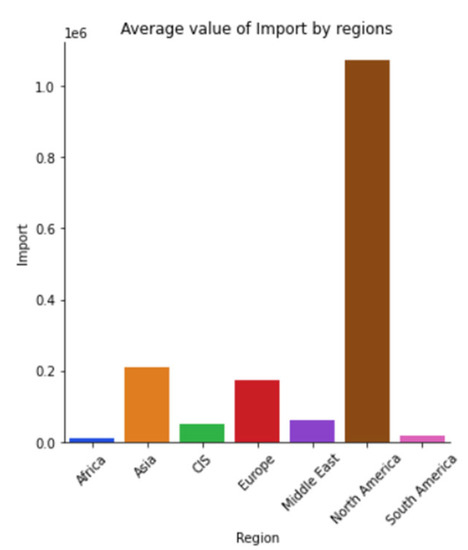

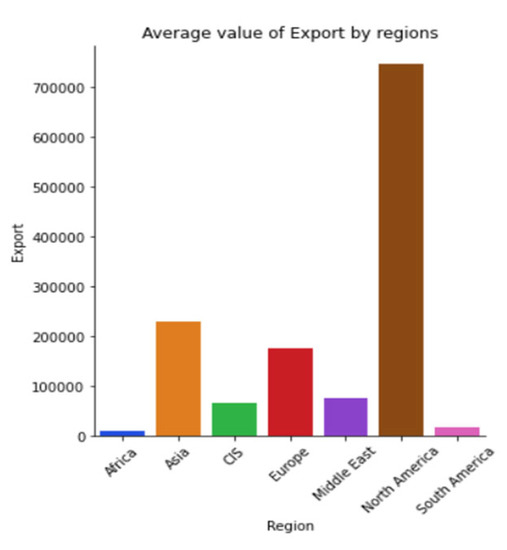

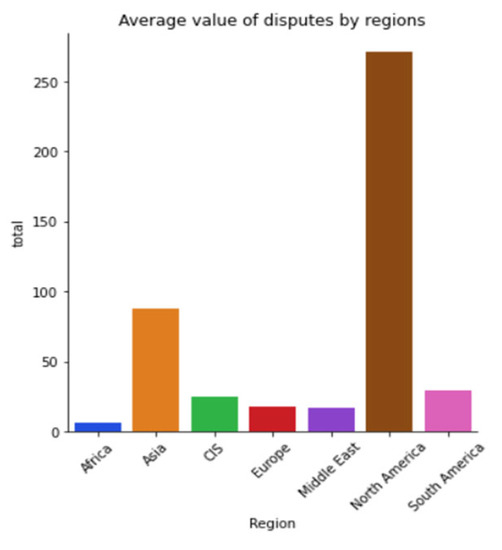

In order to analyze regional asymmetries in trade, it is suggested to consider the division of countries into seven regions: Africa, Asia, CIS, Europe, Near East, North and Central America and South America and the Caribbean. Therefore, for the sake of the research, the values of all analyzed indices have been independently calculated for subject groups that are divided into world regions and economic development level groups. Data on Ukraine indicates that it is in the Europe geographic region and in the developing-countries group.

It has been found that in 2020, two out of seven world regions accounted for over 70% of the global goods and services export volume, particularly Asia (38.57%) and Europe (37.55%), while the export of the African group was under 2% and export of South America and the Caribbean (30 countries) was only 3%. The group of developed countries exported over 62% of the whole volume, while the fraction of the least-developed countries accounted for less than 1%.

It has also been established that five out of seven world regions tied the level of customs rates for over 94% of tariff lines listed in the plan of members’ concessions. The unprecedented number of tariff lines tied at 100% was demonstrated by the CIS countries, which is explained by the fact that they all belong to the so-called RAMs group. Similar commitments have also been made by Ukraine, the European Union, China and the United States.

At the same time, the average customs tariff for agricultural products is set at 15% in all three groups, according to development level, while it fluctuates from 11% in LDCs to 2.2% for nonagricultural products in developed countries. Ukraine is unique in this regard, as it tied its average tariff rate for agricultural products at 11% (practically using 9.2%) and 5% for other groups of products (practically using 3.7%).

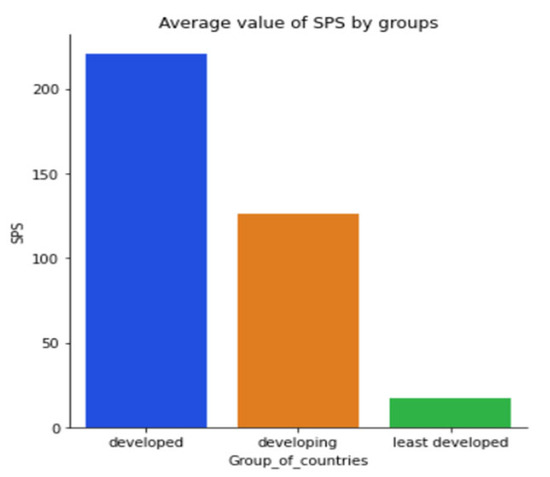

An asymmetry is also observed in members choosing a system of nontariff tools. Thus, 51.4% of all implemented measures of this type are TBTs, and 35.7% are sanitary and phytosanitary measures. Studying the group of trade protection measures, it is observed that antidumping measures are used in 86% of cases.

Among the world regions, North America is an undisputed leader in implementing nontariff measures (average-weighted index is 5,077). European countries (2,198), Asian countries (1,612) and countries of Central and South America and the Caribbean (1,393) have twice fewer indices. The least-average-weighted index belongs to CIS countries (359) and Africa (274).

The amount of time spent on compliance with norms and the cost of customs formalities are other indices worth analyzing. A common tendency lies in the fact that the poorer the region, the longer it takes to get customs clearing. Thus, in 2019, passing formalities at products exported to LDCs took 85 h and cost USD 504, to OECD countries—13 h and USD 150 and to the EU—8 h and USD 87. According to the World Bank data, passing customs formalities in Ukraine requires 6 h and costs USD 75.

The maximum number of service subsectors that appropriate commitments are made for by WTO members is 147 out of 155 (Moldova), and the minimum number is 1 (Fiji and Tanzania). At the same time, countries belonging to the LDC group do not suppose absence of commitments. For instance, Gambia made commitments in 111 service subsectors, Sierra Leone in 110, Liberia in 108, Afghanistan in 103, Cambodia in 97, etc.

The most active parties in trade disputes are the countries of North America (on average 271 disputes in every country, while in Asia the number of disputes is 88 in a country). The least-involved region is Africa, and it is mostly involved as the third party.

As of December 2021, there were 351 effective RTAs existing in the world. According to the number of parties, 81% of RTAs are bilateral and 19% are multilateral. According to geographical extension, 59% are cross-regional and 41% are in-regional. As for RTA typification, 58% are free-trade agreements, 34% are economic integration agreements, 5% are agreements with partial sphere and 3% are customs unities. Having carried out the countries analysis, it is concluded that the European Union is the leader (45 agreements), which, in turn affirms the policy of “pressing” European standards along with international ones. Ukraine is one of top-ten countries possessing this index, having 19 effective FTAs with 47 world countries, including Great Britain, Georgia, the European Union, the EFTA, Israel, Canada, North Macedonia, Montenegro and each CIS country, separately, except for the Russian Federation.

“Mega trade” agreements (often also called “trade agreements of the 21st century”) deserve special attention. The Trans-Pacific Partnership, which includes 12 countries of the Asian–Pacific region, and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the United States and the European Union, may be classified as such.

Technological and infrastructural asymmetries. In 2019, the vast majority of the population of developed countries (86.6%) had access to the Internet, and nearly two times less had it in developing countries (47%). This figure is minimal for LDCs (19.1%). As of 2020, generally, the availability of legislative acts in the electronic transactions sphere was 81%, 56% in protection of consumer rights, 66% in data confidentiality and 79% in cybersecurity. However, there are still countries (15), mostly in Africa, which lack any legal norms, while almost 20% of RTAs contain a chapter devoted to e-commerce.

Micro-, small and middle-sized enterprises, which on average account for 34% of exports in developed countries, are gaining more significance in the global trading system. There is a positive connection between the size of an enterprise and its participation in export: 9% for microenterprises, 38% for small, 59% for middle-sized and 66% for large. In developing countries, there is an inverse relationship between the number of employees that a firm has at the beginning of its activity and the number of years before it starts exporting. Large firms that started with five or fewer employees needed 17 years to start exporting products, compared to five years for those that had 60–100 employees.

Gender asymmetry. In the majority of countries, women are employed in service sectors, such as education or healthcare, which are less intensively supplied abroad. On average, enterprises led by women face 13% higher export expenses than those led by men.

All existing challenging aspects of WTO functioning may be grouped according to five key directions—inability to fully realize a mechanism for settling trade disputes, insufficient efficiency of monitoring the observance of obligations by members, low effectiveness of negotiation process, a necessity to define a country’s status within the WTO and low performance of WTO committees and working bodies.

5. Results

5.1. Analysis of Variance of the Influence of Independent Factors on the Volume of Global Trade

5.1.1. Categorization of Countries by the Level of Economic Development

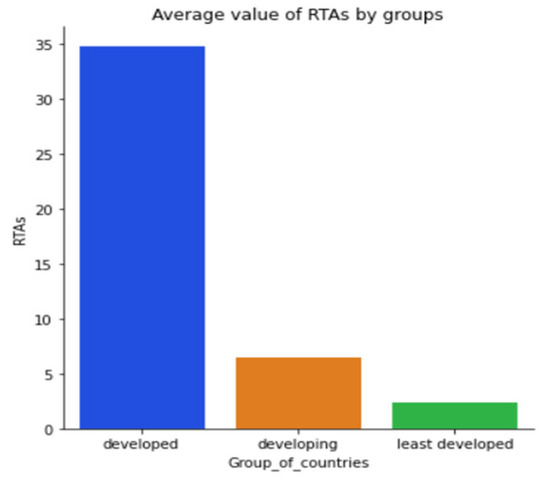

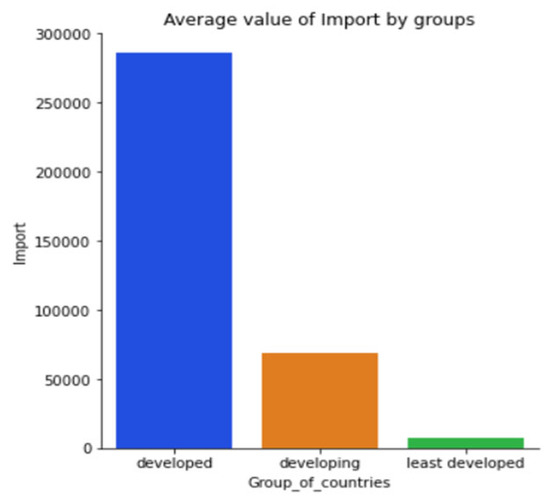

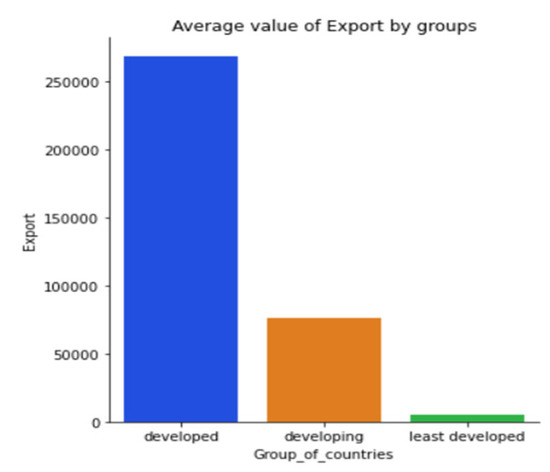

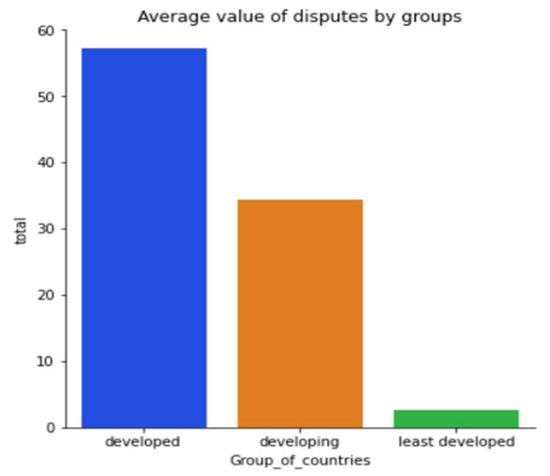

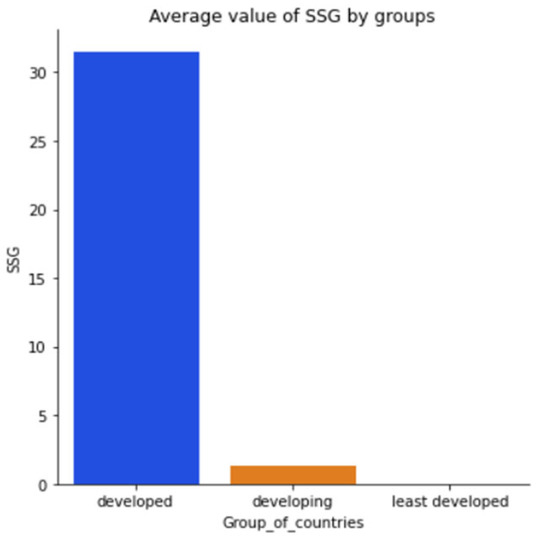

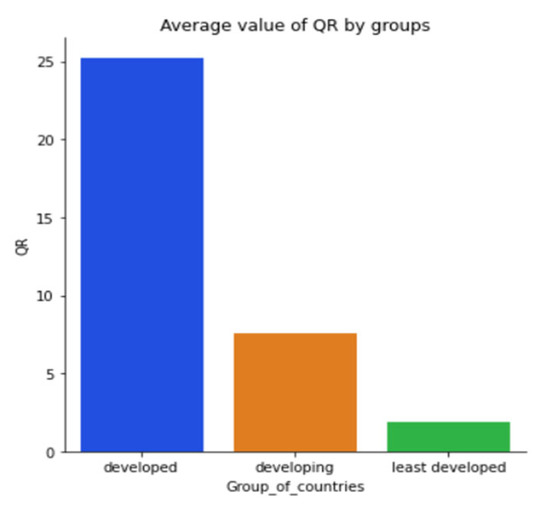

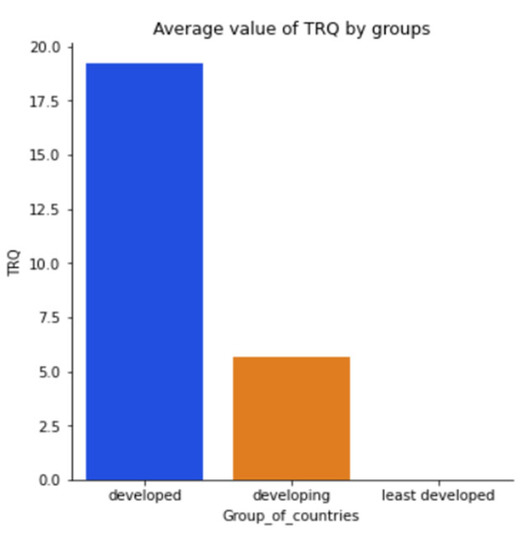

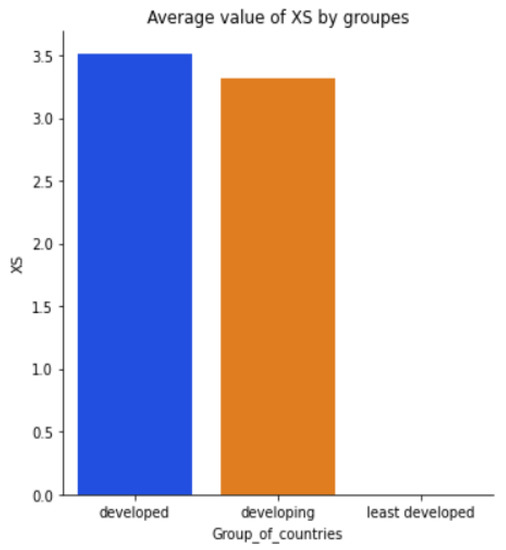

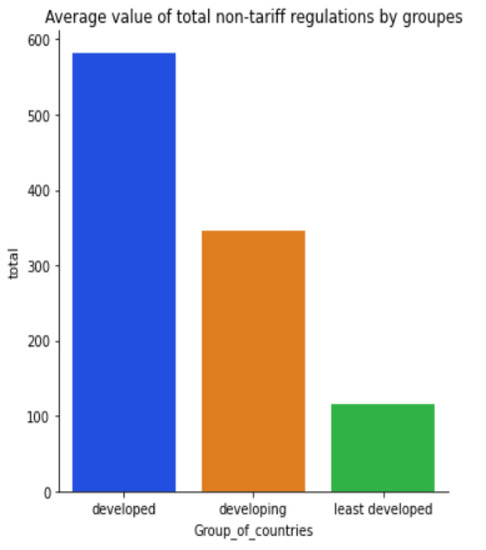

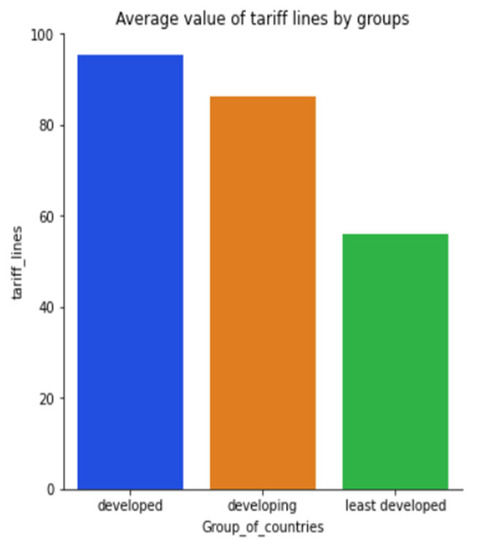

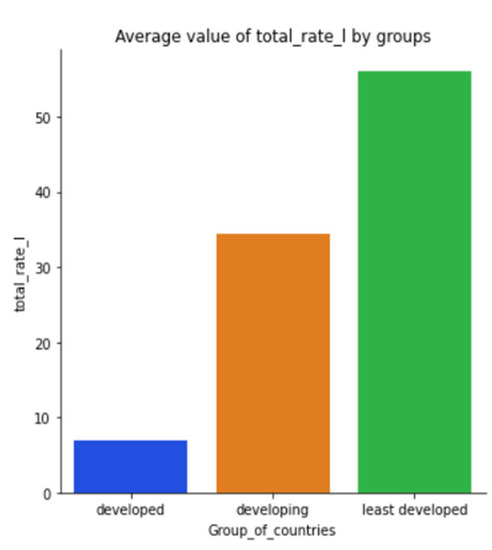

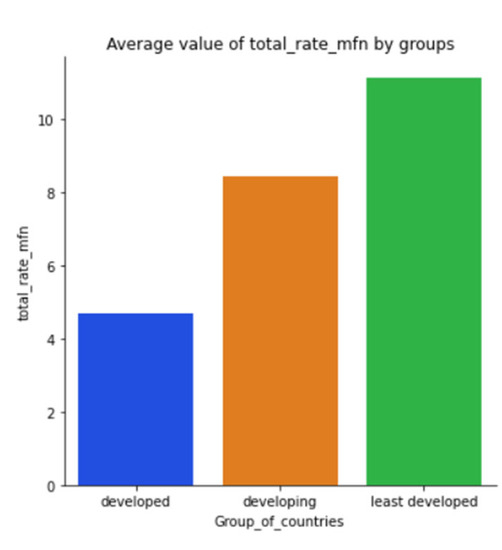

The null hypothesis to be tested is formulated as follows: the country’s membership in a certain economic group has no influence on the value of selected indicators of the latter’s foreign economic activity. In other words, the null hypothesis states that the obtained differences between group means are insignificant and caused by the influence of random factors. Then, the alternative hypothesis states that the country’s membership in a certain economic group significantly affects the value of selected indicators of the country’s foreign economic activity. The average values of the studied indicators by country groups are presented in Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4, Figure A5, Figure A6, Figure A7, Figure A8, Figure A9, Figure A10, Figure A11, Figure A12, Figure A13, Figure A14, Figure A15, Figure A16, Figure A17, Figure A18, Figure A19, Figure A20 and Figure A21 (Appendix A).

Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4, Figure A5, Figure A6, Figure A7, Figure A8, Figure A9, Figure A10, Figure A11, Figure A12, Figure A13, Figure A14, Figure A15, Figure A16, Figure A17, Figure A18, Figure A19, Figure A20 and Figure A21 above were constructed by the authors on the basis of their own calculations using data [47,48,49,50,51,52].

The results of the one-factor analysis of variance, namely, the indicator for which the analysis of variance was performed, the calculated value of the F-statistic and its significance level, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the analysis of variance for selected indicators of different levels of the factor of countries, divided by the level of economic development.

The obtained results allow us to conclude that, for most indicators, the null hypothesis is rejected. That is, the country’s membership in a certain economic group has a significant impact on the value of the studied foreign economic activity indicators of the countries. The null hypothesis was accepted for such indicators as TBT, ADP, CV, XS and agr_rate_mfn. That is, although such measures as nontariff regulation can be used as technical barriers to trade, antidumping and countervailing measures, export subsidies do not depend on the country’s membership in a certain economic group, but may be determined by the country’s geographical position (this hypothesis will be confirmed or refuted at the next stage of the research) or the specifics of the country’s foreign economic activity. The size of the average duty rate on agricultural goods within the framework of the most-favored-nation (MFN) regime also, as revealed by the results of the analysis of variance, does not depend on the country’s membership in the economic group.

Since the results of the analysis of variance showed the presence of statistically significant differences between the compared groups, we will perform a posteriori comparison using the Tukey test. Tukey’s test is a specialized parametric post hoc test for all pairwise comparisons, which is a modification of the Student’s test for pairwise comparisons. In the presented study, it was chosen because, in [62], it was proved that, when comparing the expediency of using different criteria for estimating the level of discreteness of statistics, the use of the Tukey approach shows satisfactory results for use in this study, in particular, proving to be better than using the Mud approach. The study in [63] indicated that using modifications of the Tukey test is not always the best possible method. For example, the Newman–Keuls test’s critical value, q, depends on the comparison interval. For the Tukey test, it is not the comparison interval that is used, but the number of groups, i.e., the critical value, q, is the same. The practical expediency of using Tukey’s criterion is that, by using studentized statistics for all pairwise comparisons between groups, it allows one to ensure the level of research error within the error level of the population of all pairwise comparisons. The hypotheses of the Tukey test are formulated as follows.

The null hypothesis (H0) is that the means in the two groups being compared are the same: μB = μA. The alternative hypothesis (Ha) is that the means in the two comparison groups differ: μB ≠ μA, where the subscripts A and B stand for any two comparison groups.

In case of unequal sizes of the compared groups, Tukey’s test is calculated by the formula:

where is greater than the average value between two compared samples, is less than the average value between two compared samples, and and are the numbers of observations in samples A and B, respectively. Null hypotheses of the Tukey test are accepted or rejected by comparing the calculated values obtained by Equation (4) with the determined critical value for the selected level of significance [64].

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 show p-values of Tukey’s test for each pair of groups of countries being compared. Tukey’s test was not performed for indicators for which, according to the results of the analysis of variance, the null hypothesis of equality of mean values was accepted.

Table 3.

The results of pairwise a posteriori comparison for significant indicators at different levels of the factor of groups of countries by the level of economic development according to the Tukey test.

Table 4.

Results of pairwise a posteriori comparison for indicators of nontariff trade measures of groups of countries by the level of economic development according to the Tukey test.

Table 5.

Results of pairwise a posteriori comparison for indicators of the import duty rate at different levels of the factor of groups of countries by the level of economic development according to the Tukey test.

From Table 3, it becomes obvious that the average values of the number of valid regional trade agreements differ significantly in each group of countries. The values of export and import differ significantly in the group of developed countries in comparison with others. On the other hand, although differences in the average values of these indicators in the groups of least-developed countries and developing countries exist, they cannot be called significant and explained by the country belonging to a certain economic category. Among other things, it was established that the number of trade disputes between countries and separate customs territories that were resolved within the framework of the WTO differs significantly between groups of developed and least-developed countries.

We conclude that significant differences in the number of nontariff regulatory measures are observed between the groups of developed and least-developed countries, with the exception for special safeguard measures, because this type of measure is most often used among representatives of the group of developing countries (Table 4). Between the group of developed countries and developing countries, there are also significant differences in the number of applied nontariff measures, except for sanitary and phytosanitary measures. At the same time, it was found that existing differences in the use of nontariff regulatory measures between the groups of the least-developed countries and developing countries are, as a rule, insignificant and are not explained by the country’s membership in one of the aforementioned economic groups.

As it is indicated in Table 5, the country’s membership in a certain economic group significantly affects the import duty rate, because between all groups of countries there are significant differences in the size of the import duty rate and the number of tariff lines. These differences can be explained precisely by the different levels of categorization factor of the countries by the level of economic development. The only exception is the number of bound tariff lines in developed and developing countries: existing minor differences are not due to the country’s membership in one economic group or another.

So, the following conclusions can be drawn on the basis of the results of the analysis of variance and by analyzing the average values of the studied indicators by groups of countries by the level of economic development. In general, the country’s membership within a certain economic group significantly affects the value of the indicators of the country’s foreign trade activity. In particular, developed countries are characterized by significantly higher volumes of exports and imports compared to other countries. They also conclude regional trade agreements much more often and are active participants of trade disputes (at the same time, no statistically significant difference between developed and developing countries was found for the last indicator). In addition, developed countries are the most active users of nontariff measures to regulate trade volumes. The average level of the duty rate, on the contrary, is the lowest in developed countries and the highest in the group of least-developed countries, which is a logical manifestation of the courses of trade policies of the countries’ economic leaders that aimed at the liberalization of trade in goods.

5.1.2. Grouping of Countries According to Location in a Specific Region

Results of the analysis of variance for the region factor—grouping of countries according to location in a specific region. The null hypothesis to be tested is formulated as follows: the belonging of a country to a certain geographical region has no influence on the value of selected indicators of the country’s foreign economic activity, and the obtained differences between the group average values are insignificant and caused by the influence of random factors. Then, the alternative hypothesis is that belonging to a certain geographical region significantly affects the value of selected indicators of the country’s foreign economic activity.

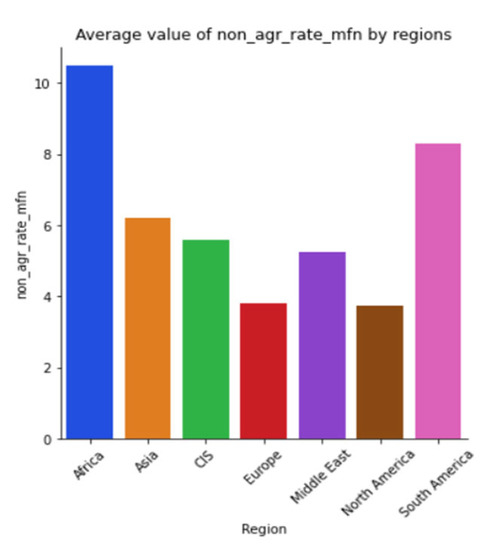

The average values of the studied indicators by region are presented in Figure A22, Figure A23, Figure A24, Figure A25, Figure A26, Figure A27, Figure A28, Figure A29, Figure A30, Figure A31, Figure A32, Figure A33, Figure A34, Figure A35, Figure A36, Figure A37, Figure A38, Figure A39, Figure A40, Figure A41 and Figure A42 (Appendix B).

With the help of univariate analysis of variance, the following results were obtained for the region variable represented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of analysis of variance of selected indicators for different levels of the factor belonging to geographical regions of the world.

According to the results of the conducted analysis of variance, we may conclude that the geographical position of the country significantly affects the studied indicators of the foreign economic activity of this country. Indicators such as export subsidies and the average rate of customs duties on agricultural goods under the most-favored-nation (MFN) regime are exceptions.

With the help of pairwise comparisons of the average values of the studied indicators by groups of countries using the Tukey test, we will check between which groups of countries there are significant differences due to the geographical location of the country or a separate customs territory (Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9).

Table 7.

The results of pairwise a posteriori comparison for significant indicators at different levels of the factor of regional affiliation of the country according to the Tukey test.

Table 8.

Results of pairwise a posteriori comparison for indicators of nontariff trade regulation measures at different levels of the country’s regional affiliation factor according to the Tukey test.

Table 9.

Results of pairwise a posteriori comparisons for import duty rate indicators at different levels of the country group factor by world region according to the Tukey test.

According to the results of the Tukey test (Table 7), it can be noted that the countries of the European region are significantly ahead of the rest of the world in terms of the number of valid regional trade agreements. On the other hand, the differences between other regions according to this indicator cannot be considered significant and are due to the geographical location of the country. According to the indicators of the volumes of exports and imports and the number of trade disputes between countries and separate customs territories, which were resolved within the framework of the WTO, the countries of North America differ significantly. The differences between the rest of the world regions cannot be considered to be statistically significant and are due to the geographical location of the country.

According to the results of the calculations given in Table 8, the influence of the factor of the country belonging to the geographical region is most significantly observed for the countries of North America: the countries of this region occupy leading positions in terms of the number of nontariff measures used to regulate trade volumes. It was also found that the geographical position of the country determines the existence of significant differences in the frequency of use of such regulatory measures as technical barriers to trade for Middle Eastern countries and quantitative restrictions for WTO members located in Asia. For the remaining groups of countries, the existence of differences in the use of certain nontariff measures of foreign trade regulation does not depend on the country belonging to a certain geographical region and may be due to the influence of other factors, including random ones. Separately, it is worth noting that for such indicators as safeguard measures and tariff quotas, the regional factor has almost no influence, that is, the existing differences between the regions of the world in the use of such tools of trade policy are not due to the geographical location of the country.

According to the results of Tukey’s test (Table 9), the existence of statistically significant differences between the countries of the African region and other regions of the world in all indicators of tariff regulation of trade volumes was revealed. Significant differences due to the geographical location of the country were also found for WTO members representing the South American region.

Therefore, the conducted analysis allows us to conclude that the factor of belonging of a country or a separate customs territory to a certain geographical region significantly affects the indicators of foreign trade activity of such subjects. In particular, statistically significant differences from other regions of the world in terms of export and import volumes were found for the North America region. This region is also the most actively involved in trade disputes and uses nontariff trade regulation measures. The number of valid trade agreements is the highest among the countries of the European region. In addition, the regional factor determines the existence of statistically significant differences in the average customs duty rate in African and South American countries—in these regions, the customs duty rate is significantly higher compared to other regions of the world (Table 10).

Table 10.

Results of analysis of variance for selected indicators, 2020.

That is, on the basis of the results of the analysis of variance, it becomes possible to draw the general conclusion that the level of development of the country and its geographical location significantly affect the value of all the studied indicators, with the exception of the average duty rate provided under the most-favored-nation (MFN) regime for agricultural goods. Such a difference is natural because this duty rate is actually applied by countries and separate customs territories to goods defined by the WTO members as necessary for the creation of state reserves for food security purposes, so it is a specific category of goods that are not subject to general trends and rules regarding elimination of trade barriers.

5.2. Econometric Analysis of the Influence of Selected Indicators of Foreign Trade Activity on the Volume of Global Exports

In addition, in order to evaluate the impact of selected indicators of foreign trade activity on the country’s export volume, an econometric analysis was conducted. For this purpose, a linear multivariable econometric model was used, the general form of which is described by the following equation [46]:

where y is the dependent variable, x1, …, xk are the independent variables, βk is the unknown estimates of model parameters, and ε is the stochastic component of the econometric model.

To carry out the econometric analysis, the same initial statistical data as for the analysis of variance were used. The amount of goods exported in USD million was chosen as the dependent variable—Export, and a number of indicators of the country’s foreign trade activity will act as independent variables, namely, RTAs, Disputes_total, SPS, TBT, ADP, CV, SG, SSG, QR, TRQ, XS, non_tarif_total, tariff_lines, total_rate_l, total_rate_mfn, agr_rate_l, agr_rate_mfn, non_agr_rate_l and non_agr_rate_mfn, which were characterized above in detail.

It should be noted that all the indicators that were measured in physical units, were previously logarithmized. This allows one, firstly, to reduce the asymmetry of the distribution of a statistical value. Secondly, using not the absolute values of the indicators but their natural logarithms, all estimates of the βk model parameters can be interpreted as elasticity coefficients, that is, to determine the percentage change in the dependent variable when the independent variable k increases by 1% [64].

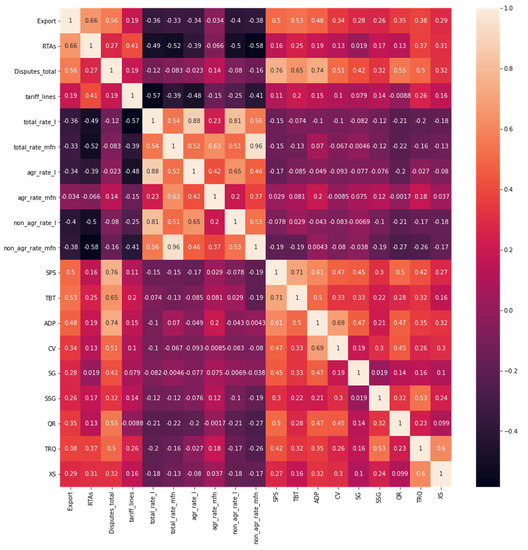

To avoid the problem of multicollinearity, the correlation matrix (Figure A43) and the variance inflation factor (VIF) of the determined indicators were calculated in the previous stage of the research.

A visual analysis of the pairwise correlation coefficients between pairs of independent variables in the correlation matrix, as expected, showed a strong correlation between the average total tariff rate and the average tariff rates for agricultural and nonagricultural goods, as well as between the average MFN tariff rate and the average tariff rate for nonagricultural goods under the most-favored-nation regime. Accordingly, it can be assumed that the above-mentioned pairs of indicators can be collinear and to avoid multicollinearity in the array of independent variables, it is advisable to remove one or more of the mentioned indicators.

In order to conduct a more thorough analysis and make a decision on the removal of some independent variables, the variance inflation coefficients were calculated, step by step removing the indicators that had the largest VIF value until the VIF indicator for all independent variables did not exceed the recommended value of “10” [65]. The values of the VIF coefficients for the initial set of independent variables and after stepwise removal of the variables total_rate_mfn and total_rate_l are given in Table 11.

Table 11.

The value of the inflation coefficient of the VIF in the array of independent variables—indicators of foreign trade activity.

Thus, the total_rate_mfn variable was deleted in the first step, the total_rate_l variable was deleted in the second step and as a result, 16 variables remained in the array of independent variables. Their list and the calculated values of the VIF coefficients are given in Table 12 (values of VIF coefficients for SPS and TBT variables exceed 10 by less than 1, so they are taken into account in further analysis).

Table 12.

VIF value for the final set of independent variables to be used in the econometric analysis.

Four econometric models were built to analyze the impact of the selected indicators of the country’s foreign trade activity on the export value. The first one is a generalized model based on the entire data set, which includes information on 150 countries and separate customs territories of the world.

Among other things, since the results of the analysis of variance showed that the country’s membership in a certain category according to the level of economic development has a significant impact on most of the studied indicators of foreign trade activity, it is considered appropriate to separately build econometric models for groups of developed countries, developing countries and the least-developed countries. This will allow for a more detailed analysis of each group of countries and to determine a specific set of indicators that has the greatest impact on the number of exports in a particular economic group.

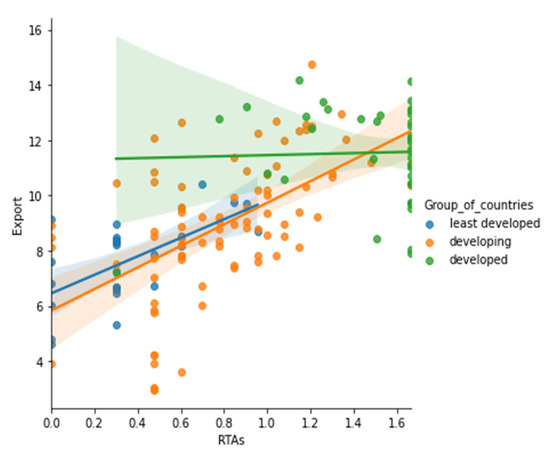

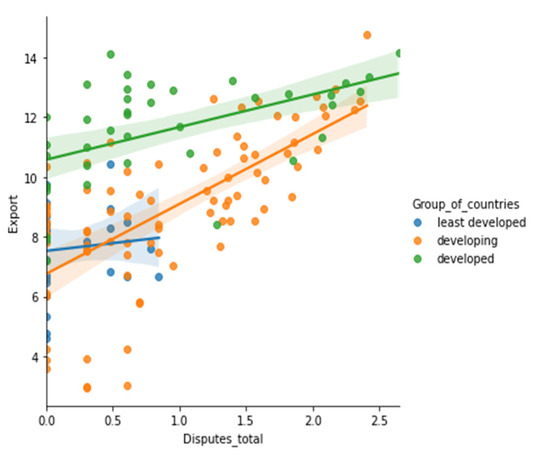

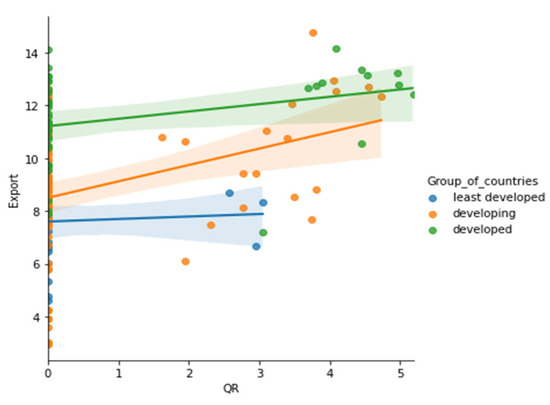

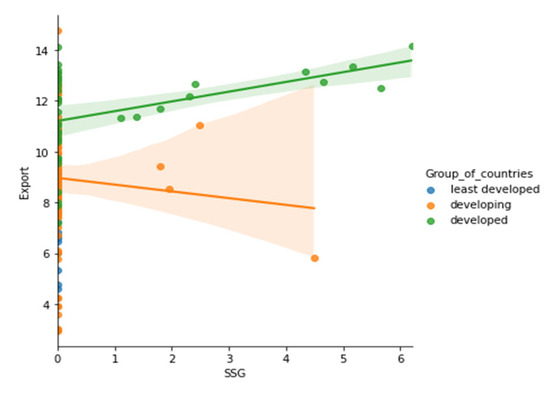

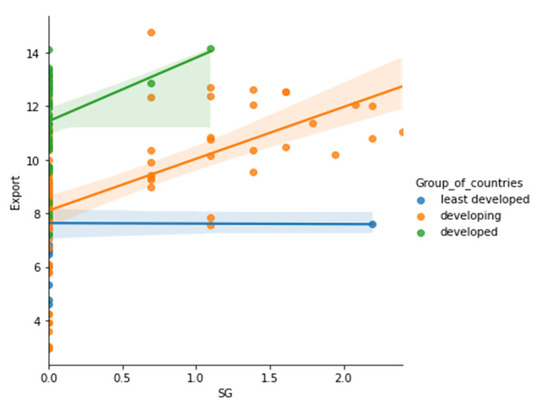

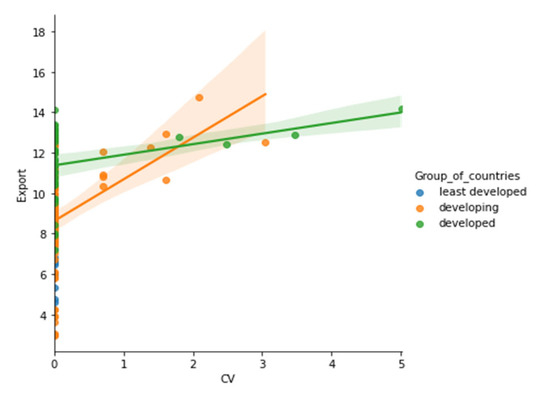

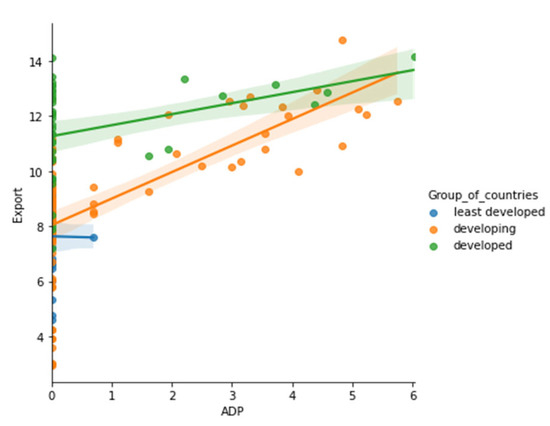

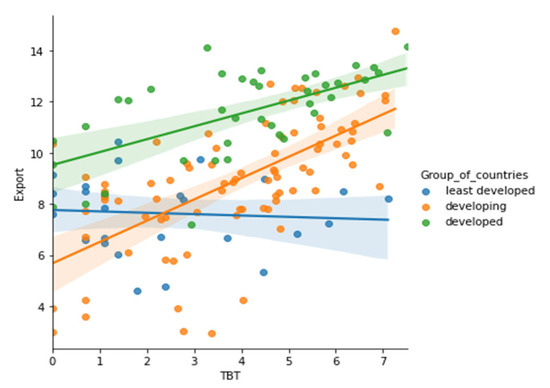

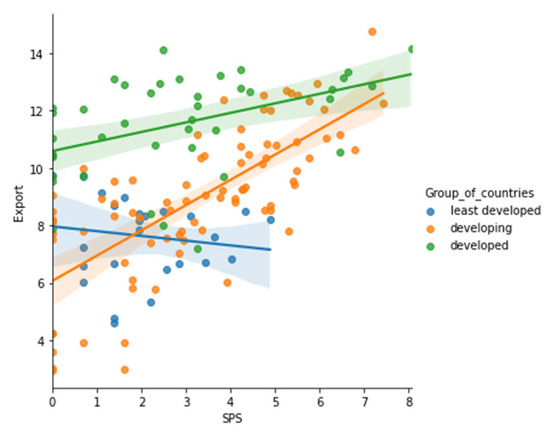

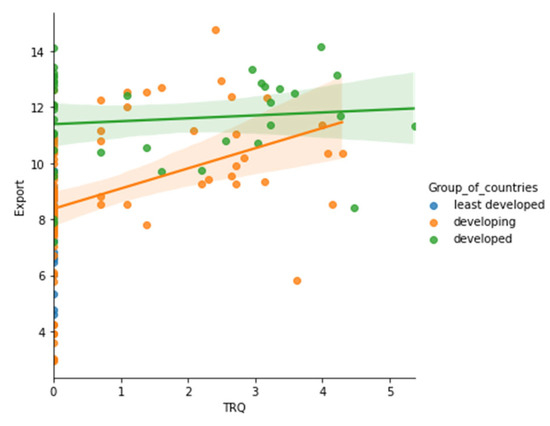

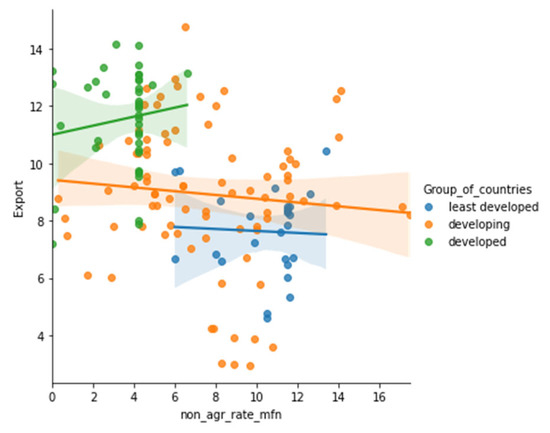

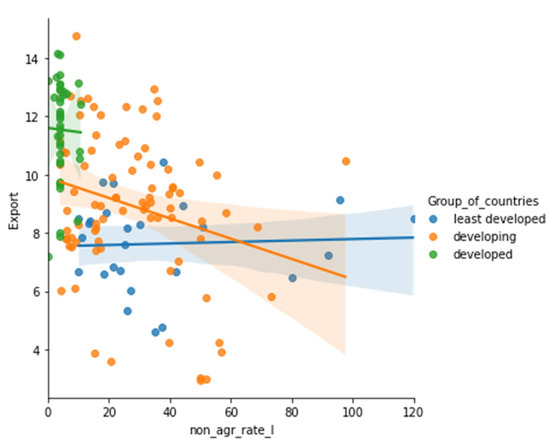

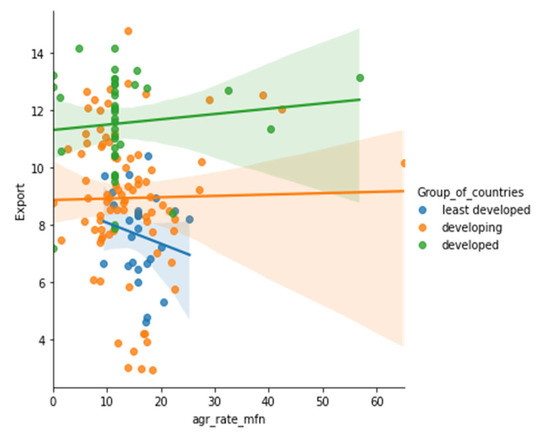

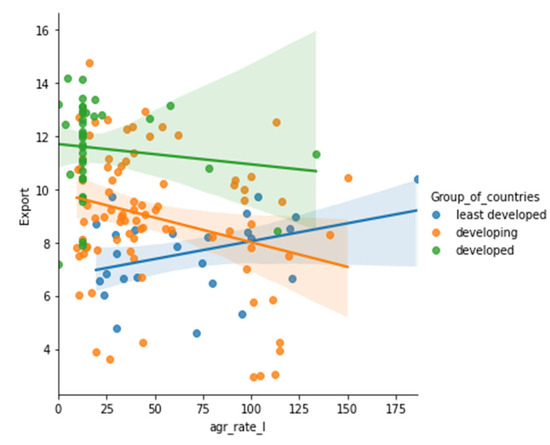

In addition to the results of the analysis of variance, the expediency of building econometric models for different groups of countries is also evidenced by the graphical presentation of regression lines for each economic group, separately, in the correlation field of points.

As it is shown in Figure A44 and Figure A45, the regression lines for the three groups of countries that are different in the level of economic development differ significantly. This means that the construction of econometric models for each group of countries is appropriate and will allow a more accurate approximation of the data.

A graphical presentation of the regression lines in the correlation field of points for the remaining independent variables is presented in Figure A46, Figure A47, Figure A48, Figure A49, Figure A50, Figure A51, Figure A52, Figure A53, Figure A54, Figure A55, Figure A56 and Figure A57 (Appendix C).

The following regression equation was obtained for the complete data set:

The value of the adjusted coefficient of determination is 0.650. The value of the F-statistic coefficient is 56.440. Verification by F- and t-tests showed that the model and estimates of its parameters are significant, which indicates the adequacy and satisfactory quality of the obtained model. The number of current regional trade agreements has the greatest influence on the volume of world exports—with a 1% increase in the number of concluded agreements, the volume of exports increases by almost 2.5%. In addition, the increase in the number of trade disputes between countries and separate customs territories that were resolved within the framework of the WTO and technical barriers to trade has a positive effect on the export volumes [66]. At the same time, the increase in the duty rate on nonagricultural goods somewhat slows down the growth of exports.

The regression equation for the group of developed countries looks like this:

For this level, the value of the adjusted coefficient of determination is 0.692, and the value of the F-statistic is 11.940. According to the results of F- and t-tests, it was found that the model as a whole and the estimates of its parameters are statistically significant. Using the equation, it can be concluded that indicators such as the number of valid regional trade agreements and the number of trade disputes resolved within the WTO have the greatest positive impact on demand in developed countries: an increase in these indicators by 1% leads to an increase in exports in the country by 3.7% and 2.4%, respectively. It is worth noting that it is for developed countries that the above-mentioned indicators have the greatest stimulating effect on exports in comparison with other economic groups. In addition, such nontariff regulatory measures can act as technical barriers and safeguard measures (increasing the use of these regulatory measures by 1% allows exports to increase by 0.39% and 0.29%, respectively), as well as introduce of quantitative restrictions and tariff quotas (an increase in the use of these nontariff regulatory instruments by 1% can lead to a decrease in exports by 0.44% and 0.46%, respectively). At the same time, the increase in the average rate of customs duties on agricultural goods leads to a slight decrease in exports in developed countries.

For developing countries, the following regression equation was obtained:

For this model, the adjusted coefficient of determination is 0.675, and the value of Fisher’s F-statistic is 25.590. Verification by F- and t-tests showed that the model and the estimates of its parameters are significant, which indicates the adequacy and satisfactory quality of the obtained model. The number of valid regional trade agreements has a positive effect on the export volumes. It is worth noting that, in the group of developing countries, exports are the least-sensitive to changes in the number of trade agreements: a 1% increase in the number of concluded trade agreements causes an increase in exports by only 1.1%. Similar to developed countries, in developing countries, the increase in the average rate of customs duties on agricultural goods leads to a slight decrease in exports. It has also been established that the use of such nontariff instruments as sanitary and phytosanitary measures, technical barriers to trade, antidumping and special safeguard measures has a positive effect on the amount of exports in developing countries.

And the export regression equation for the least-developed countries looks like this:

It is immediately worth noting that the adjusted coefficient of determination is only 0.409, which is the lowest indicator among the four constructed models. The value of the Fisher statistic is 6.778.

The model constructed according to the results of the F-test is statistically significant and of sufficient quality. However, according to the results of the t-test, only the number of valid regional trade agreements has a statistically significant effect on the volume of exports in the least-developed countries. The rest of the considered indicators do not have a statistically significant effect on the amount of exports, which is explained by the minimal level of use of nontariff measures to regulate trade volumes by countries of this economic category.

6. Novelty of the Study and of the Results

This research identified and systematized the existing asymmetries of the global trade system, which have direct and indirect impacts on its development. Special attention is paid to the study of the impact of the global trade system asymmetries of the use of tariff and nontariff instruments of export and import regulation by countries and individual customs territories, depending on their belonging to a certain geographical region or group of countries with a certain level of economic development. Critically, taking into account the structure, scope and subject composition, the tendency for the increased number of regional trade agreements was analyzed, and the influence of the digitization of international trade, and the growing role of micro-, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and that of enterprises led by women on the growth volumes and degree were characterized as a diversification of trade flows.

In this study, the complex analysis and systematization of the asymmetries of the global trade system (as a subsystem of the global economic system at the global, regional and international levels) were further developed by assigning them to two key groups: asymmetries directly related to international trade processes (asymmetries in trade in goods, caused by differences in the levels of customs tariffs of countries, the number and variability of applied nontariff measures to regulate trade volumes, including such trade protection measures as antidumping, compensatory and special measures, the degree of involvement of countries and individual customs territories in the resolution of trade disputes; asymmetries in trade in services that proceed from differences in the levels of specific obligations of countries regarding the liberalization of access to service markets); asymmetries that are indirectly related to the processes of international trade (technological–infrastructural, gender, informational, by subjectivity, in particular, taking into account the growing role of micro-, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) in the export activity of countries).

7. Discussion

The results of this study confirm the existence of asymmetries of different natures and origins. A significant number of asymmetries was observed precisely in the sphere of trade in goods, taking into account the tools used by countries. For example, the number of tariff lines in respect of which WTO members have bound customs rates, as well as the very levels of the bound and actually applied (under the most-favored nation (MFN)) duty rates for agricultural and nonagricultural goods, differ critically, depending on the regional and development belonging to a participant in the global trade system. The key reason for trade asymmetry is the use of nontariff regulatory measures, namely, sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPM), technical barriers to trade (TBT), trade protection measures (antidumping, compensatory and special), quantitative restrictions, tariff quotas, etc., as well as frequency of introduction, which increases annually. Another characteristic difference between different groups of countries is their ability to protect their national economic interests, not only with the help of trade protection measures listed above, but also by initiating the consideration of trade disputes within the framework of the appropriate mechanism in the WTO. The specific obligations of WTO members to provide access to services markets have been the subject of discussions for more than a decade. This is because, out of 152 subsectors of services, some countries have opened only 1 and some 144, and such openness is not always characteristic of countries with a high level of economic development.

No less significant is research on the asymmetry of other aspects that have an indirect effect on trade processes. Thus, as of 2021, one of the global problems remains the so-called “digital divide” between developed and developing countries. That is, the lack of free and unhindered access to the Internet in a number of African, Asian and South American countries automatically deprives them of the opportunity to participate in the trade of digital products and electronic commerce, or simply the digitization of individual trade procedures in order to simplify and speed it up, for example, transferring trade to a paperless format—another trend of the 21st century. There is support for the export activities of micro-, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), which have significant difficulties accessing foreign markets due to the lack of up-to-date information about the trade regimes of other countries, as well as higher costs and risks for enterprises of this type when conducting international trade, etc. Gender asymmetry remains no less relevant, because women in trade still have difficulties with access to quality education and areas of trade in goods with high added value, and the export value of products from a company headed by a woman is still more than 10% higher in cost than a similar one headed by a man.

However, the key asymmetry of the global trade system in today’s conditions is the exponentially growing number of regional trade agreements (RTAs), which create alternative regional rules for regulating trade flows. In the context of the lack of significant practical results of multilateral trade negotiations within the framework of the WTO in the form of new multilateral agreements, this creates a threat to the existence of the entire global trade system in its usual format.

The results of this study confirm the previously obtained results indicating that RTA boosts trade between member countries. Anderson et al.’s last work [67] assessed the impact of regional trade agreement growth within the framework of general equilibrium. The main lesson of this study is that trade affects the growth of consumer and producer prices, which promotes or hinders the accumulation of physical capital. At the same time, growth affects trade directly through changes in the size of the country and indirectly by changes in the frequency of trade costs. In addition, the conducted study confirms that the active participation of the European Union in international trade is supported by its active participation in different RTAs. This idea is supported by Yatsenko et al. [15], who emphasize that, for many countries, a free-trade agreement with the European Union becomes a driver for economic and social development.

The research provides the conclusion that one of the advantages of FTAs is the possibility for the country to obtain the image of being the regional leader and can also be used as a platform for implementing new international trade rules. This idea is backed by Suominen [68], who describes RTAs as “incubators of new trade rules”. On the other hand, we should not leave out the possible restraining factors that suppress future RTA development and mostly deal with the fear of losing the country’s independence in some spheres connected with international trade. That is why some authors, Bazaluk et al. [69], in particular, support the idea that RTAs can be seen in both ways—as tools for trade liberalization and as tools for trade protectionism.

Bhagwati et al. [70] are some of the critics of regionalism trends. They describe regional integration as being “preferential” or even “discriminatory.” Although many international trade studies note that the net effect of international economic integration on economic welfare depends on the actual situation, Bhagwati et al. [70] argue that a negative net effect is more likely than a positive one and that regional integration is a stumbling block to global liberalization rather than its building block. In their opinion, economic integration entities such as the European Union lead to a significant diversification of trade rather than its development in quantitative and, especially, qualitative aspects. Economic synthesis among western European countries was discriminatory towards third countries for two reasons: due to the elimination of customs payments and other trade restrictions between members of the union and due to unilateral changes in customs tariffs when the European Commission introduced a single customs tariff in relation to all nonmember countries of the European Union.

Even before the establishment of the WTO, Bhagwati et al. [71] proposed a reform of the GATT with the aim of ensuring as little as possible redirection of the trade flows, necessarily caused by economic integration. They also believed that the formation of free-trade areas should be prohibited, and the formation of customs unions and common markets as the “lesser evil” could be allowed, provided that the single customs tariff for each customs category should be set at the lowest level among the previously applied tariffs and not the average level, as was usually done. These proposals, according to Bhagwati et al. [71], certainly made the new regional integrations more open and liberal towards other participants of the trade system that do not belong to them.

The latest wave of regionalism in the world has obviously raised concerns that it will slow down and weaken the global liberalization process. Regional integration can become a characteristic trap that “captures” its participants and prevents them from overcoming domestic political opposition to global free trade. Levy [72] believes that regional integration undermines political support for global free trade because bilateral and regional free-trade agreements cannot increase political support for multilateral free trade.

Bhagwati also tried to argue that regional integration can force GATT/WTO members to abandon multilateral negotiations for liberalization, partly because bureaucrats prefer to negotiate with neighboring countries, and partly because big capital expects to get better deals in the region. According to the views of similarly minded scientists, two points point to the conclusion that the participants of international economic integration entities are not interested in significant global liberalization. First, members of such integrations cannot achieve significant economies of scale outside of global liberalization—their integration cannot be large enough to fully satisfy their needs. Second, members of such integrations might prefer to use their political energy to create and manage their integrations rather than global negotiations [73].

Therefore, the issue of the coexistence of WTO and RTU agreements was raised even before the start of the organization’s operation. The parties to the GATT of 1947 foresaw the possibility of concluding RTUs by agreeing on the relevant rules, which, in turn, contributed to the signing of the first of such agreements in the 1950s and 1960s of the 20th century. However, since the 2000s, which in turn coincided with the start of the next round of multilateral trade negotiations within the framework of the WTO (“Doha-Development” round), the number of new RTUs began to grow at an accelerated pace.

There are countless theories that explain this pattern: some focus on the study of the pressure of lobby groups on exporters, others on the interests of developing countries when using RTUs as a tool to attract foreign direct investment, and others on geopolitical considerations. One of the explanations for the rapid spread of RTUs is the lack of significant progress in multilateral negotiations in the WTO system since its creation. Members negotiate under standard modalities with the principle of a single undertaking, according to which nothing is agreed-upon until all members agree on all provisions. Also complicating the course of multilateral negotiations and the conclusion of the Doha Development round, in particular, is the change in the dynamics of political economy among WTO members, caused by the accelerated growth of powerful developing countries, whose interests differ significantly from the interests of the advanced economies of the organization’s founding countries.