Abstract

The objective of this study is to identify the role of Chinese tourists’ shopping values in the formation of their outcome variables. This study more specifically proposes that two dimensions of shopping values, which include utilitarian and hedonic shopping values, positively affect brand prestige. In addition, it was hypothesized that brand prestige helps in regard to enhancing well-being perceptions and brand preference. It was also proposed that well-being perceptions and brand preference have a positive influence on word-of-mouth. This study also hypothesized the moderating role of country image in the proposed model. The survey responses were collected from 634 Chinese duty-free tourists. The data analysis results showed that both utilitarian and hedonic shopping values significantly affect brand prestige. Moreover, brand prestige was found to be a significant determinant of well-being perceptions, and well-being perceptions positively affect brand preference. Brand preference is a critical factor affecting word-of-mouth. Lastly, country image played a moderating role in the relationship between brand prestige and well-being perceptions and brand preference and word-of-mouth.

1. Introduction

Shopping plays an important role in the tourism industry because many tourists travel mainly for shopping [1,2]. The importance of shopping is no exception in the Korean tourism industry. Chinese tourists who shop in duty-free shops in Korea are, in particular, currently drawing a lot of attention. Korean tourism statistics reported that Chinese tourists accounted for 35.6% of foreign tourists who visited Korea in January 2019, which is up 28.7% on a year-on-year basis [3]. Duty-free shops highly rely on Chinese tourists because more than approximately 70% to 80% of purchases in duty-free shops come from Chinese tourists [4]. More than 60 duty-free shops in Korea are trying hard to attract Chinese shopping tourists for this reason [5].

It is widely accepted that shopping value is the key factor that enhances the tourists’ overall satisfaction [6,7,8], and the concept of value has been consistently applied in the context of shopping tourism for this reason [9,10,11]. Value can be defined as an overall assessment of the benefits that the consumers receive for the costs that are paid by the consumer [12,13]. This means that the overall value would be low if the benefits were not large enough for the payments that were made. Understanding value is important and meaningful because it has a significant impact on a company’s success [14,15]. Very few studies have examined Chinese shopping value in the context of duty-free shops from a duty-free shop’s point of view, even though it is important to understand Chinese shopping value. Thus, this study was designed in order to examine the shopping values in the context of a duty-free shop.

The current study was also designed to, firstly, explore the moderating role of country image in the field of duty-free shops. It is widely accepted that country image has an important effect on consumer behavior [16,17]. Lee and Lockshin [18] also suggested that a country’s image as a tourism destination positively affects the consumer’s perception of a certain product, which is made at a particular destination. This means that consumer buying behavior depends on the country of origin of a product. For example, if tourists have a positive image of a country, they tend to judge that the quality of the products that are sold in that country is also good. It is therefore significant to identify that tourist behavior depends on what tourists think of the image of the country that they visit.

In summary, this study was designed in order to examine the importance of shopping value in the context of duty-free shops. This study more specifically proposes the effect of two sub-dimensions of shopping value, which include utilitarian and hedonic shopping values, on brand prestige. In addition, it was hypothesized that brand prestige helps to increase well-being perceptions and brand preference, which has a positive influence on word-of-mouth. Lastly, the current study investigated the moderating role of country image in the proposed model. It is expected that the results of the current study will help the managers of duty-free shops in order to develop marketing strategies that are based on the shopping values of Chinese tourists.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Shopping Value

Shopping value has been consistently examined by many researchers in the tourism industry because it is deemed to be a significant factor that affects tourists’ overall satisfaction [6,7,8]. Value can be defined as “the customer’s overall appraisal of the net worth of the service that is based on the customer’s assessment of what is received, which is the benefits that are provided by the service, and what is given, which is the costs or sacrifice in regard to acquiring and utilizing the service” [19] (p. 1765). This means a trade-off between the overall benefits that are received and the sacrifices that are made by the consumer [12]. The scholars applied values to consumer behavior in the early days based on one dimension [20]. However, many researchers pointed out that one dimension has limitations in regard to explaining consumer behavior because consumers consider other values when they buy products/services [21,22]. Many scholars have tried to identify the multidimensional values in shopping tourism for this reason. The following two multidimensional values are widely accepted and employed in shopping tourism and include (1) utilitarian shopping value and (2) hedonic shopping value.

Utilitarian value is more specifically associated with functional, practical, and task-related aspects, whereas hedonic value is related to pleasure-seeking and experiential and emotional arousal [6,23]. Thus, if consumers prefer utilitarian value, they will consider monetary value, convenience, and time-saving first when purchasing products/services [13,24]. On the other hand, if consumers consider hedonic value to be important, they are more likely to focus more on fun and playfulness when they buy products/services [6,25]. In addition, Kesari and Atulkar [26] also suggested that monetary saving and convenience play an important role in the formation of utilitarian value, whereas entertainment and exploration help in order to enhance hedonic value. Moreover, hedonic value is evaluated according to a more subjective perspective when compared with utilitarian value because hedonic value is a more affective inclination [6,27].

Lai [28] suggests that customers evaluate the benefits of products based on their consumption behaviors in order to attain the desired consumption values. Satisfaction is a crucial aspect of consumer behavior research, and it is impacted by the shopping values of tourists [29]. These values, which include utilitarian and hedonic values, also influence shopping experiences and can shape the shopping attitudes and purchase intentions of tourists [30]. The previously conducted studies categorized shopping values into two dimensions that include utilitarian values, which comprise functional and task-related values, and hedonic values, which include pleasure-seeking values [6,31]. Utilitarian values are linked to the effortless procurement of necessary goods, whereas hedonic values arise from exciting and enjoyable shopping experiences [6,32]. The prior research confirmed that both utilitarian and hedonic shopping values significantly influence consumer behavior and decisions [6,33]. For instance, Kesari and Atulkar [26] investigated the factors that influence utilitarian and hedonic values, and they discovered that monetary savings, selection, and convenience have a substantial positive impact on utilitarian value, whereas entertainment, exploration, and place attachment have a significant positive impact on hedonic value.

2.2. Effect of Shopping Value on Brand Prestige

The concept of brand prestige has been studied in diverse fields, such as luxury cruises, first-class flights, private country clubs, casinos, and coffee shops [34,35,36,37,38]. Brand prestige is defined as the products/services, which are related to the brand, being positioned higher than other brands [39,40]. The intrinsic, superior, and exclusive know-how factors are known as the important factors in regard to evaluating the level of brand prestige [41]. In addition, consumers who buy a prestigious brand in order to show that they are different from others are called prestige-brand seekers [36,40].

This study proposed the relationship between shopping values and brand prestige. First, the relationship can be supported by the Value–Attitude–Behavior (VAB) model. The VAB model has been widely applied in various fields in order to explain consumer behavior. The VAB model can be defined by the following sentence: “The influence should theoretically flow from abstract values to mid-range attitudes to specific behavior” [42] (p. 638), which suggests that values play an important role in the formation of attitude and behavior. This means that if tourists have a high level of value at a duty-free shop, they would feel that the duty-free shop has a high status. In addition, consumers more importantly judge the level of brand prestige based on the value that the brand gives them [43], which suggests that perceived value is an important predictor of brand prestige. The empirical studies also showed a significant relationship between shopping value and brand prestige. For example, Ok, Choi, and Hyun [44] developed a research model in order to find the influence of perceived value on brand prestige in the coffee industry. Their results showed that hedonic value is a critical factor that affects brand prestige. Furthermore, Hwang and Han [36] found that cruise tourists perceive a high level of brand prestige when they receive a convenient and fun service. The following hypotheses are proposed, which are based on the following theoretical and empirical backgrounds.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Utilitarian shopping value has a positive influence on brand prestige.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Hedonic shopping value has a positive influence on brand prestige.

2.3. Effect of Brand Prestige on Well-being Perceptions and Brand Preference

This study proposes next how brand prestige affects well-being perceptions and brand preference. First, well-being perception refers to “the extent that a particular consumer good or service creates the overall perception of the quality of life” [45] (p. 289). The concept of well-being perceptions is very important in the tourism industry because travelers want to improve their quality of life via travel [46,47]. In addition, this study proposed the effect of brand prestige on well-being perceptions. Buying products or services from a prestigious brand is considered a means of improving one’s quality of life because it reflects a certain level of affluence and social status. As such, it is associated with a higher subjective quality of life [34,48]. According to Ahn et al. [34], customers who have a high level of prestige from a certain brand would think that the brand met their overall well-being needs in regard to the airline industry. Moreover, Hwang and Lee [46] also showed that brand prestige aids in regard to forming well-being perceptions in the tourism industry. Therefore, the following hypothesis can be proposed.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Brand prestige has a positive influence on well-being perceptions.

Brand preference can be defined as “the extent that the customer favors the designated service that is provided by a certain company compared to the designated service that is provided by other companies in his or her consideration set” [19] (p. 1765). Consumers have difficulty selecting products because they are exposed to various brands when they buy a product [49]. The consumers in this situation put their preferred brands first in order to reduce risk [50]. It is therefore very important for companies to imprint their brand on the consumers and cause them to have high levels of brand preference. It is more importantly widely accepted that brand prestige is a key predictor of brand preference. For instance, Hwang [51] examined the effect of brand prestige on brand preference in the fine-dining restaurant industry. They analyzed 293 restaurant patrons and suggested that brand prestige positively affects brand preference. Hwang and Han [37] also investigated the relationship between brand prestige and brand preference using 228 casino players. They discovered that when casino players perceive a high level of brand prestige from a certain casino brand, they tend to prefer that casino brand. Consumers buy products that are from a prestigious brand because they believe that the brand’s image aligns with their self-concept [40]. In addition, individuals seeking prestige are inclined to associate a prestigious brand image with their own identity [52]. Hence, if tourists perceive that a duty-free shop has a strong sense of prestige, they would prefer the duty-free shop.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Brand prestige has a positive influence on brand preference.

2.4. Effect of Well-Being Perceptions on Brand Preference and Word-of-Mouth

Customers want to have a high level of quality of life with their consumption [53], so they would prefer a duty-free brand when the tourists perceive that their quality of life is enhanced via shopping at the duty-free shop. According to Hwang and Hyun [54], airline passengers perceive that flying in first class is considered a significant factor in enhancing their quality of life, so they would be interested in what other passengers think about taking a first-class flight. Hwang and Lee [46] also suggested that tourists are more likely to be passionate about a travel agency when they perceive that the package tour met their overall well-being needs. The following hypothesis is proposed, which is a result of the arguments above.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Well-being perceptions have a positive influence on brand preference.

The concept of word-of-mouth means “informal communication directed at other consumers about the ownership, usage, or characteristics of particular goods and services and/or their sellers” [55] (p. 261). Word of mouth plays a very important role in regard to consumer behavior because people tend to trust more information from people such as family or friends as opposed to commercial advertising [15,56,57]. It is significant and meaningful to identify how to form word-of-mouth for this reason.

Hwang and Hyun [54] also investigated how well-being perceptions affect loyalty using 202 first-class airline travelers in the USA. They indicated that well-being perceptions are an important factor influencing loyalty. Hwang and Lee [46] proposed a research model in order to find the positive relationship between well-being perceptions and brand loyalty using 331 senior tourists in Korea. They showed that when the tourists feel that their quality of life is enhanced during a tour, they would have a high level of brand loyalty. If a person who is seeking prestige believes that consuming a particular brand improves their quality of life, they are more likely to have a strong inclination toward the brand [58,59]. It can be argued that having a positive perception of well-being has a positive impact on word-of-mouth recommendations.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Well-being perceptions have a positive influence on word-of-mouth.

2.5. Effect of Brand Preference on Word-of-Mouth

Many previous studies have confirmed the relationship between brand preference and word-of-mouth. For instance, Jin et al. [60] suggested that brand preference is a critical factor affecting word-of-mouth in the restaurant industry. This means that when customers have a high level of brand preference, they would recommend a restaurant to their friends or others. Hwang et al. [32] discovered that if customers have a high level of preference for a certain coffee brand, they would say positive things about the coffee brand to others.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Brand preference has a positive influence on word-of-mouth.

2.6. Moderating Role of Country Image

Many studies were conducted on country image because it significantly affects consumer behavior [61,62]. Country image refers to “the total of all descriptive, inferential, and informational beliefs that a person has about a particular country” [63] (p. 193). Roth and Diamantopoulos [62] (p. 727) more specifically defined country image as “a generic construct that consists of generalized images that are created not only by representative products but also by the degree of economic and political maturity, historical events and relationships, culture and traditions, and the degree of technological virtuosity and industrialization”. It is widely known that country image consists of affective and cognitive image, which has a significant influence on product attitudes and destination beliefs [17,62]. First, cognitive image is created by the individual’s beliefs and knowledge that he/she already has about an object [64,65]. On the other hand, affective image is formed by a connection with the emotions of an object [65,66]. These types of images serve as an important extrinsic cue when consumers purchase their products [67].

The moderating role of country image can be explained by the halo effect. The halo effect refers to a phenomenon in which the salient characteristics of an object affect the evaluation of other characteristics of the object [68]. The halo effect also plays an important role in regard to explaining consumer behavior. Consumers tend to be somewhat hesitant when they purchase an unfamiliar product, and they are more likely to evaluate the quality of the product at this time, based on the image of the country it is produced in [69,70]. Country image is an important aspect of shopping tourism because it has a significant impact on the tourists’ perception and decision-making regarding the destination [71]. This means that the image of a country plays a crucial role in regard to creating a positive impression of the destination and enhancing the tourists’ experiences. A favorable country image can contribute to attracting tourists, which increases the length of their stay and boosts their spending [72]. Tourists are more likely to choose a destination that aligns with their preferences and expectations, which are heavily influenced by country image. Empirical studies also support this argument. Wang et al. [73] discovered that consumer behavior varies depending on the image of the country. Vijaranakorn and Shannon [74] showed that national image plays a role in regard to increasing the value of the product and consumer purchase intention. Islam and Hussain [75] more recently revealed that the image of the country decreases consumer uncertainty and increases product purchase intention. The following hypotheses are proposed, which are based on the theoretical backgrounds.

Hypothesis 8a (H8a).

Country image moderates the relationship between utilitarian shopping value and brand prestige.

Hypothesis 8b (H8b).

Country image moderates the relationship between hedonic shopping value and brand prestige.

Hypothesis 8c (H8c).

Country image moderates the relationship between brand prestige and well-being perceptions.

Hypothesis 8d (H8d).

Country image moderates the relationship between brand prestige and brand preference.

Hypothesis 8e (H8e).

Country image moderates the relationship between well-being perceptions and brand preference.

Hypothesis 8f (H8f).

Country image moderates the relationship between well-being perceptions and word-of-mouth.

Hypothesis 8g (H8g).

Country image moderates the relationship between brand preference and word-of-mouth.

2.7. Proposed Model

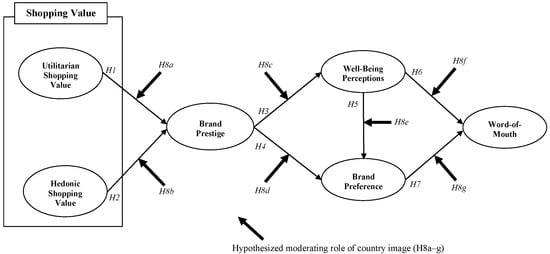

The current study suggests the following research model with 14 hypotheses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement

The validated measurement items were cited from the existing literature, and they were slightly modified to ensure their appropriateness in the shopping industry in order to empirically measure the seven constructs in the proposed model. First, two dimensions of shopping values, which included utilitarian and hedonic values, were measured using six items from Sirakaya-Turk et al. [8] and Han et al. [76]. Second, brand prestige was measured using three items that were adapted from Baek et al. [43] and Hwang and Lee [46]. Third, well-being perceptions were measured using three items that were borrowed from Grzeskowiak and Sirgy [45] and also Hwang and Lee [46]. Fourth, brand preference was measured using six items that were cited from Hellier et al. [19] and Kim, Ok, and Canter [77]. Fifth, word-of-mouth was measured using three items that were adapted from Hennig-Thurau, Gwinner, and Gremler [78] and Hwang and Choi [25]. Lastly, country image was measured using six items that were adapted from Lee, Lee, and Lee [79] and San Martín and Del Bosque [80], which included economically developed, high living standards, advanced science and technology, peace-loving, friendly, cooperative, and likable. The items in the questionnaire were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale, which ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

3.2. Data Collection

An online survey was performed in China to evaluate the proposed hypotheses in the proposed model. First, the respondents answered a screening question before they started the survey: “Have you shopped at duty-free shops in Korea within one year?” If a respondent responded “no”, the survey was terminated. However, if the respondent replied yes, the respondents were then given the second question in order to select a duty-free shop that they had most recently visited and were then asked to answer all the questions. The data were collected from 634 Chinese duty-free tourists via an online survey company’s system, and the data were employed for the statistical analysis.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 indicates the profile of the survey respondents. Of all the respondents, 47.3% were male tourists, and 52.7% of them were female tourists. Their mean age was 32.63 years old. A total of 64% of the respondents held a bachelor’s degree in regard to education level. In addition, 84.4% of the respondents (n = 535) were married. Furthermore, 65% of the respondents were company employees, which is followed by 17.2% having professional employment (n = 109). Lastly, 34.6%, which is the highest percentage of the respondents (n = 156), indicated an income that ranged between US$ 27,771 and US$ 37,000.

Table 1.

Profile of survey respondents (n = 634).

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The results revealed that the CFA model has a reasonable fit (χ2 = 238.290, df = 118, p < 0.001; NFI = 0.968, IFI = 0.984, CFI = 0.984, TLI = 0.979, and RMSEA = 0.040) (Table 2 and Table 3). All the factor loadings were equal to or higher than 0.785 (p < 0.001). The values for the composite reliability ranged from 0.853 to 0.887. These values exceed the suggested level of 0.7, which suggests a satisfactory level of internal consistency [81]. In addition, the values of the average variance extracted (AVE) for all of the constructs were higher than the 0.5 threshold value [82], which indicates that convergent validity was statistically supported. Lastly, the AVE value for each construct was greater than the square correlation between all the possible pairs of constructs, which suggests an acceptable level of discriminant validity [83].

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis: items and loadings.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and associated measures.

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

SEM was performed in order to check whether the proposed hypotheses are statistically significant or not. The overall evaluation of the model fit indicated an adequate fit of the model (χ2 = 278.511, df = 124, and p < 0.001; NFI = 0.963, IFI = 0.979, CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.974, and RMSEA = 0.044). The data analysis results, which include the path-standardized parameters and the correspondent t-values, are shown in Table 4. The results of the SEM analysis statistically supported five of the seven hypotheses.

Table 4.

Standardized parameter estimates for the structural model.

4.4. Moderating Role of Country Image

A multiple-group analysis was used in order to check the moderating role of country image, which is based on the comparison of the chi-square difference between the unconstrained and constrained models in regard to the difference in the degrees of freedom.

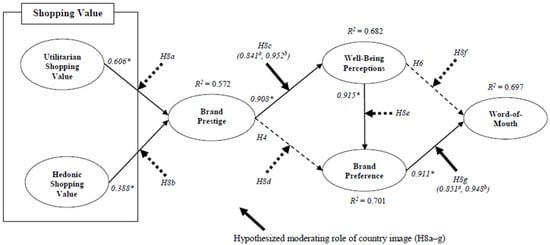

The results of the data analysis indicated that country image plays an important moderating role in the relationship between brand prestige and well-being perceptions (Δχ2 = 4.784 > χ2 = 0.5(1) = 3.84, df = 1), which supports Hypothesis 8c. The path coefficient for the high-country-image group (β = 0.952) was more specifically higher than it was for the low-country-image group (β = 0.841). Second, the moderating role of country image in the relationship between brand preference and word-of-mouth was confirmed (Δχ2 = 5.720 > χ2 = 0.5(1) = 3.84, and df = 1). This result showed that the effect of brand preference on word-of-mouth is significantly different across the level of country image, which supported Hypothesis 8g. The path coefficient between brand preference and word-of-mouth was 0.948 (p < 0.05), which is in regard to the high-country-image group. On the other hand, the path coefficient was 0.851 (p < 0.05) for the low-country-image group.

However, Hypotheses 8a (Δχ2 = 0.421 < χ2 = 0.5(1) = 3.84 and df = 1), 8b (Δχ2 = 1.255 < χ2 = 0.5(1) = 3.84 and df = 1), and 8e (Δχ2 = 0.453 < χ2 = 0.5(1) = 3.84 and df = 1) were not statistically supported, which is contrary to expectations. Figure 2 provides the results of the multiple-group analyses.

Figure 2.

Standardized theoretical path coefficients. Notes: * p < 0.05, dashed lines indicate non-significant paths (p > 0.05); a path coefficient for the low-country-image group; and b path coefficient for the high-country-image group.

In addition, the R2 values for brand prestige, well-being perceptions, brand preference, and word-of-mouth in the proposed model were 0.572, 0.682, 0.701, and 0.697, respectively.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, this study examined tourists’ perceived shopping values and their outcomes. The concept of shopping value in the tourism industry refers to the customers’ overall appraisal of the net worth of a shopping experience, which includes its utilitarian and hedonic value [6,8,23]. The study focused on the concept of brand prestige as an outcome of perceived shopping values. Brand prestige refers to the products/services that are related to the brand being positioned higher than other brands [39,40]. Customers judge the level of brand prestige based on the value that the brand gives them [43,44], so the present study proposed H1 and H2. The results revealed that these two hypotheses were statistically supported. The path coefficient of H1 was higher than H2, which is unlike previous studies in the food service context [35,44]. It can be interpreted that utilitarian value is more important than hedonic value in regard to forming brand prestige because duty-free shops should accomplish the shoppers’ needs about what they need and what they are looking for, which is unlike the hall-service context. This study presents a theoretical contribution as the first finding that identifies the predictors of a duty-free shop’s brand prestige.

Second, the study investigated the outcomes of the brand prestige of a duty-free shop. The study adopted the concept of well-being perceptions and brand preference as the outcomes of brand prestige. Well-being perception is the extent to which a particular product/service creates the overall perception of quality of life [45], and brand preference is the extent to which a customer favors the designated product/service that is provided by a specific company compared to other companies [19]. The extant studies supported the effect of brand prestige on well-being perceptions and brand preference [34,37]. The result of the hypothesis tests revealed that H3, H5, and H7 were statistically supported. However, H4 was not statistically supported. It is not in line with the study about fine-dining restaurants’ customers [51] or the study about casino players [37]. Using a high-prestige brand can reflect the customer’s social status, so they might prefer those brands. The duty-free shops have high-prestige brands, so if it is a brand without a specific product that travelers want, they may not prefer the brand. In other words, travelers have to meet a specific experience in order to prefer the high-prestige brand, which is a well-being perception that was found in this study. In addition, H6 was also not statistically supported. Travelers experiencing a well-being perception with first-class airlines can recommend it as a memorable experience [54]. Travelers may perceive a sense of well-being at duty-free shops, but it would be remembered as just one of the good experiences of their trip. Nevertheless, the travelers’ well-being perception of duty-free shops influenced brand preference, which led to word-of-mouth. This study found an essential role of brand preferences in regard to forming word-of-mouth in the context of the shopping experience at duty-free shops, which is unlike the previous studies on travelers’ well-being perceptions [46,54]. These findings present a theoretical extension that identified the sequential relationship, which included brand prestige, well-being perceptions, brand preference, and word-of-mouth intentions, in the context of tourists’ shopping behavior in a duty-free shop.

Third, the present study investigated the moderating role of a country’s image. Country image is an individual’s total of all the informational, descriptive, and inferential beliefs about a particular country [62,63]. The study proposed the moderating role of country image, which is grounded in the halo effect theory [68,70]. The result revealed that H8c and H8g were statistically supported. Both paths showed that the high-country-image group’s path coefficient is stronger than the low-country-image group. However, the moderating role of country image was not statistically supported in regard to forming brand factors, such as H8a, H8b, and H8e. Travelers can experience a brand in the country that they traveled to as well as also in their own or other countries. It can be interpreted that country image might not be important in regard to preferring duty-free shop brands and evaluating a brand’s prestige. The present study consequently has a theoretical extension that found the halo effect in the travelers’ shopping experience in duty-free shops by identifying the moderating role of country image.

5.2. Managerial Implications

First, utilitarian shopping value is the most positive factor in regard to forming the brand prestige of a duty-free shop. This study measured utilitarian shopping value as an assessment of whether the customers are buying what they want and really need during their shopping experience. The managers of duty-free shops can conduct customer research in order to understand their needs, such as focus group interviews. They should continuously gather customer feedback and use it in order to improve the utilitarian value by listening to what the customers need and want and by making changes to products. In addition, marketers should consider in-depth visual merchandising methods in order to easily find the products that shoppers are looking for. The customer research and interview suggested above should also be reflected in the product display.

Second, hedonic shopping value also influences the brand prestige of a duty-free shop. The marketers of duty-free brands can improve brand prestige by providing hedonic shopping value. For instance, the cosmetic brand Lancôme hosted its inaugural Blooming Rose Spring Festival event, which was in partnership with a China Duty-Free Group [84]. The duty-free store space was transformed into a digital rose wonderland, which incorporated the existing art and light installation. Lancôme provided a pleasant and happy experience for duty-free shoppers via this event. The marketers of duty-free brands should also break away from typical duty-free brand managing and host events via partnerships with brands that are located in duty-free shops in order to provide hedonic shopping value to tourists.

Third, country image strengthens the effect of brand prestige on well-being perceptions and the effect of brand preference on word-of-mouth intentions. The marketers can leverage country image in order to enhance the tourists’ well-being perceptions and word-of-mouth intent. For example, the color red symbolizes China. Red paper cuts and couplets, which are used when decorating for the Chinese Lunar New Year, include red flowers and red lanterns. Lancôme gave the shoppers a feeling of being in China by dyeing the shopping mall red via the event that is explained above [84]. The marketers can improve country image with colors or symbols by reflecting the national characteristics of the duty-free shop brand. For instance, the managers at duty-free shops in Korea can consider the Hanbok uniform, which is the Korean traditional dress. It would enhance the travelers’ perception of the country image of Korea.

6. Conclusions

This study successfully identified the tourists’ shopping values and their consequences in the context of a duty-free shop. The study proved H1, H2, H3, H5, and H7, which included utilitarian and hedonic value, brand prestige, well-being perceptions, brand preference, and word-of-mouth intentions. The study also partially found the moderating roles of the country image, H8c and H8g, in which paths were strengthened by the country image. These findings present theoretical contributions and managerial suggestions in the context of duty-free shop brands. It is the first finding that identifies the predictors of a duty-free shop’s brand prestige. The present study also proved the halo effect of country image in the context of the tourists’ shopping behavior in a duty-free shop. In addition, the study suggested focus group interviews and visual merchandising methods in order to enhance the utilitarian shopping value. The study also suggests event marketing via partnerships with brands that are located in duty-free shops in order to enhance hedonic shopping value and country image.

Nevertheless, the current study has some research limitations. First, the data that were used in this study were measured in one survey, which might be the reason for the likelihood of a common method bias [85]. Future studies should devise data collection methods that reduce the likelihood of a common method bias, such as observing shopping tourists’ mobility [86]. Second, the findings of this study are difficult to generalize in other countries because the study only involved Chinese tourists. There may, in particular, be differences in customer responses depending on the cultural dimensions [87]. This leads to a low level of external validity, so the study suggests future research that applies cross-cultural differences. Third, social values can also influence the tourists’ responses and behavior in addition to utilitarian and hedonic values [15,88,89]. It is recommended to use a comprehensive framework that includes social values or other values in future research. Lastly, the demographic factors, which include gender, age, marital status, occupation, education level, and income, can be considered as control variables, but the present study overlooked them. The study suggests future research about travelers’ shopping behavior by considering these demographic factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and I.K.; methodology, J.H.; software, J.H.; validation, J.H.; formal analysis, J.H.; investigation, K.J.; resources, J.H.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H., I.K. and K.J.; writing—review and editing, J.H. and I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Choi, M.; Law, R.; Heo, C.Y. An investigation of the perceived value of shopping tourism. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Choi, M. Examining the asymmetric effect of multi-shopping tourism attributes on overall shopping destination satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Tourism Statistics Data Lab. Available online: https://datalab.visitkorea.or.kr/datalab/portal/nat/getForTourForm.do (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- The Korea Herald. Available online: https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20221007000623 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Korea Duty-Free Shops Association. Available online: http://www.kdfa.or.kr/ko/pr/realtimenews.php?P=2& (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.M. Consumer shopping value, satisfaction and loyalty in discount retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2008, 15, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirakaya-Turk, E.; Ekinci, Y.; Martin, D. The efficacy of shopping value in predicting destination loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1878–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M.; Çömen, N. Tourist shopping: The relationships among shopping attributes, shopping value, and behavioral intention. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Vázquez, M.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Oviedo-García, M.Á. Shopping value, tourist satisfaction and positive word of mouth: The mediating role of souvenir shopping satisfaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1413–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A. Tourist shopping habitat: Effects on emotions, shopping value and behaviours. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaru, D.; Purchase, S.; Peterson, N. From customer value to repurchase intentions and recommendations. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 23, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Singer, J. Customer satisfaction and value as drivers of business success for fine dining restaurants. Serv. Mark. Q. 2006, 28, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Understanding first-class passengers’ luxury value perceptions in the US airline industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, A. Post-Travel Consumption Country of Origin Effects of International Travel Experiences. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, S.; Papadopoulos, N.; Kim, S.S. An integrative model of place image: Exploring relationships between destination, product, and country images. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Lockshin, L. Reverse country-of-origin effects of product perceptions on destination image. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Iniesta-Bonillo, M.Á. The concept of perceived value: A systematic review of the research. Mark. Theory 2007, 7, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahtola, O.T. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Mark. Lett. 1991, 2, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S. Demographic and motivation variables associated with Internet usage activities. Internet Res. 2001, 11, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, J. An investigation of passengers’ psychological benefits from green brands in an environmentally friendly airline context: The moderating role of gender. Sustainability 2017, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesari, B.; Atulkar, S. Satisfaction of mall shoppers: A study on perceived utilitarian and hedonic shopping values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottet, P.; Lichtlé, M.C.; Plichon, V. The role of value in services: A study in a retail environment. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.W. Consumer values, product benefits and customer value: A consumption behavior approach. Adv. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Babin, B.J.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, E.J.; Griffin, M. Modeling consumer satisfaction and word-of-mouth: Restaurant patronage in Korea. J. Serv. Mark. 2005, 19, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Littrell, M.A. Touristsߣ shopping orientations for handcrafts: What are key influences? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2005, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Chih, W.H.; Liou, D.K.; Yang, Y.T. The mediation of cognitive attitude for online shopping. Inf. Technol. People 2016, 29, 618–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.J. The antecedents and consequences of memorable brand experience: Human baristas versus robot baristas. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, E.; Florsheim, R. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping goals: The online experience. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Kim, I.; Hyun, S.S. Critical in-flight and ground-service factors influencing brand prestige and relationships between brand prestige, well-being perceptions, and brand loyalty: First-class passengers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.G.; Ok, C.M.; Hyun, S.S. Relationships between brand experiences, personality traits, prestige, relationship quality, and loyalty: An empirical analysis of coffeehouse brands. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. Examining strategies for maximizing and utilizing brand prestige in the luxury cruise industry. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. A model of brand prestige formation in the casino industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1106–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H.; Choo, S.W. A strategy for the development of the private country club: Focusing on brand prestige. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1927–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, E.J. Basic Marketing: A Managerial Approach, 9th ed.; Irwin Publishing: Burr Ridge, IL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, J.B.; Batra, R.; Alden, D.L. How perceived brand globalness creates brand value. J. Int. Bus. Studies 2003, 34, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Czellar, S. Prestige Brands or Luxury Brands? An Exploratory Inquiry on Consumer Perceptions. Available online: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:5816 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Kim, J.; Yu, J.H. The differential roles of brand credibility and brand prestige in consumer brand choice. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, C.; Choi, Y.G.; Hyun, S.S. Roles of Brand Value Perception in the Development of Brand Credibility and Brand Prestige. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/refereed/ICHRIE_2011/Wednesday/13/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Grzeskowiak, S.; Sirgy, M.J. Consumer well-being (CWB): The effects of self-image congruence, brand-community belongingness, brand loyalty, and consumption recency. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2007, 2, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. Antecedents and consequences of brand prestige of package tour in the senior tourism industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Joldersma, T.; Li, C. Understanding the benefits of social tourism: Linking participation to subjective well-being and quality of life. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. A review and a conceptual framework of prestige-seeking consumer behavior. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 1999, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.H.; Lattin, J.M. Development and testing of a model of consideration set composition. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensch, D.H. A two-stage disaggregate attribute choice model. Mark. Sci. 1987, 6, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. Brand Preference and Its Impacts on Customer Share of Visits and Word-of-Mouth Intention: An Empirical Study in the Full-Service Restaurant Segment. Master’s Thesis, Kansas State University, Kansas, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bizman, A.; Yinon, Y. Engaging in distancing tactics among sport fans: Effects on self-esteem and emotional responses. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 142, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Image congruence and relationship quality in predicting switching intention: Conspicuousness of product use as a moderator variable. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 37, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. First-class airline travelers’ tendency to seek uniqueness: How does it influence their purchase of expensive tickets? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.A. Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Han, H. Working-holiday tourism attributes and satisfaction in forming word-of-mouth and revisit intentions: Impact of quantity and quality of intergroup contact. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C. The effect of service evaluations on behavioral intentions and quality of life. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kim, J.J. Emotional attachment, age and online travel community behaviour: The role of parasocial interaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3466–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Lee, S.; Jun, J.H. The role of brand credibility in predicting consumers’ behavioural intentions in luxury restaurants. Anatolia 2015, 26, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lu Wang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Barnes, B.R.; Zhang, H. The asymmetric influence of cognitive and affective country image on rational and experiential purchases. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 2153–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.P.; Diamantopoulos, A. Advancing the country image construct. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, I.M.; Eroglu, S. Measuring a multi-dimensional construct: Country image. J. Bus. Res. 1993, 28, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Uysal, M. Market positioning analysis: A hybrid approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 987–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Ryan, C. Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Country as brand, product and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. In Destination Branding, 2nd ed.; Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., Pride, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett, R.E.; Wilson, T.D. The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.M. Country image: Halo or summary construct? J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.K.; Douglas, S.P.; Nonaka, I. Assessing the impact of country of origin on product evaluations: A new methodological perspective. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, F.; Leung, H.H.; Cai, L.A. The influence of destination-country image on prospective tourists’ visit intention: Testing three competing models. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 811–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nisco, A.; Mainolfi, G.; Marino, V.; Napolitano, M.R. Tourism satisfaction effect on general country image, destination image, and post-visit intentions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 21, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Li, D.; Barnes, B.R.; Ahn, J. Country image, product image and consumer purchase intention: Evidence from an emerging economy. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaranakorn, K.; Shannon, R. The influence of country image on luxury value perception and purchase intention. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2017, 11, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Hussain, M. How consumer uncertainty intervene country of origin image and consumer purchase intention? The moderating role of brand image. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, W. Role of shopping quality, hedonic/utilitarian shopping experiences, trust, satisfaction and perceived barriers in triggering customer post-purchase intentions at airports. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3059–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ok, C.; Canter, D.D. Value-driven customer share of visits. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, J. Dynamic nature of destination image and influence of tourist overall satisfaction on image modification. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, H.; Del Bosque, I.A.R. Exploring the cognitive–affective nature of destination image and the role of psychological factors in its formation. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFNI Magaznie. Available online: https://www.dfnionline.com/latest-news/lancome-china-duty-free-host-blooming-spring-festival-event-08-02-2023/ (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, I. Change and stability in shopping tourist networks: The case of Seoul in Korea. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Cultural constraints in management theories. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1993, 7, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Seyfi, S.; Ari Ragavan, N.; Jaafar, M. Effects of perceived value on satisfaction and revisit intention: Domestic vs. international tourists. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Callarisa, L.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Moliner, M.A. Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).