Abstract

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) heavily relies on expatriates to meet the needs of their labor market, especially in the private sector. Nonetheless, to reduce the increasing rate of unemployment the government has recently implemented a new Saudization quota in restaurants/cafés. The new Saudization policy aims to replace foreign workers with up to 50% locals. This research takes the first attempt to examine the perceptions, commitment, and attitudes of local workers, who newly joined this career after the new quota in October 2021, versus foreign workers toward careers in restaurants/cafés. A quantitative research approach was used, including a self-administered questionnaire for a sample of 408 local workers and 455 foreign workers in a random sample of restaurants/cafés. The results showed statistically significant differences between local and foreign workers in relation to nature of work, perceived social status, working conditions, career development, relationship with managers and co-workers and commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés. Despite foreign workers having higher education and experience in comparison to their local counterparts, they received less compensation, albeit they have positive perceptions, attitudes, and commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés. The negative perceptions, attitudes and commitment to a career in restaurants and cafés held by newly joined local workers have several implications for scholars and practitioners in the restaurant business. It is crucial that restaurant managers in KSA recognize the heterogeneity of their restaurant/café workers, especially after the new Saudization quota, for proper management of their human assets and sustainable performance.

1. Introduction

In 2016, the government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has launched the 2030 Saudi Vision. The 2030 Vision aims to develop a diverse economy with a robust and sustainable bottom line by localizing businesses and fostering entrepreneurship instead of heavy reliance on oil [1]. One of the 2030 Saudi Vision’s objectives is to reduce the national unemployment rate from 12.9% to 7% [2]. On the other side, KSA is one of the nations that largely relies on expatriates, especially for occupations that are not desired by local people, such those in restaurants and cafés [3]. Therefore, the government has adopted a localization strategy, which involves hiring local people instead of foreign workers [4]. The roots of localization policy refer to 1970 under the title “Saudization” [5]. However, the policy was implemented successfully in the public sector, even though it was not effective in the private sector [6]. The Saudi Development Plan 1970–1975 aimed to have up to 75% Saudis in all sectors [5]. Since Saudis were more eager to join the public sector than the private sector, this objective was not achieved successfully. Foreign workers encompassed the vast majority of employees in the private sector at that time; hence, this target was difficult to achieve [5].

The Saudi Development Plan 2006–2010 had some further initiatives by the government to impose localization strategy by proposing a new quota of 30 Saudization in the private sector. However, the quota was not fulfilled since the Saudis’ participation to the private sector did not exceed 10% in many private sectors [6]. Consequently, in 2011, the Saudi government launched a new mechanism titled “Nitaqat”. Based on the “Saudization” of their workforce, the Nitaqat system classified private enterprises into four categories: red, yellow, green, and platinum [6], to enforce private businesses to implement the quota. Enterprises in the red category are those that failed to act in accordance with Nitaqat requirements, whereas the platinum included enterprises that adopt perfect procedures and meet the Saudization policy of 30% adequately [7]. Businesses that fall under the red or yellow categories are subject to penalties for not complying with Saudization quota. For instance, businesses under red category are not allowed to renew the visas of their foreign employees or hire additional foreign employees, while businesses with yellow labels are restricted from extending the visas of their foreign employees for more than six years [7]. This Nitaqat strategy was criticized because it placed more emphasis on quantitative factors, such as the number of Saudi workers employed, than on their actual contribution or whether they are competent to perform their job or not [3,8].

Since October 2021, the Saudi Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development (HRSD) [9] has announced a new quota for restaurants inside centers/shopping malls to localize at least 40%, and for restaurants outside centers/shopping malls to localize at least 20% of their workforce. Additionally, cafés inside shopping malls and centers are forced to employ 50% Saudis compared to 30% local workers for cafés outside these facilities [9]. The HRSD Ministry has established several incentives to motivate cafés/restaurants to apply the new quota. These incentives included (1) a 50% wage subsidy by ministry for a certain period of time; (2) training for job seekers; (3) reimbursement for transportation from and to the workplace; (4) reimbursement for transportation to other cities/areas (for work); and (5) a childcare allowance to support working mothers.

Despite the above-mentioned motivations, restaurants and cafés encounter several obstacles in implementing this new quota. First, local workers lack the required skills for working in restaurants [3]. Second, Saudi people have negative perceptions and attitudes toward working in food production and the service industry [4]. They often view such jobs as minimal and bad jobs. Third, Saudi youth are less interest in physically demanding jobs with a poor image, such as restaurants [4]. Fourth, the salary offered by restaurants/café is unsatisfactory for Saudis [4]. Fifth, the worldwide negative reputation of restaurants for career advancement opportunities [10]. Sixth, the culture and social status of Saudi people, which enforce them to reject working in certain occupations, such as restaurants [3], and promote a low level of commitment toward the food service industry [11].

Earlier research [3,4,11] on the hospitality and tourism industry in KSA showed that managers believe that foreign workers are hard workers and fit to the nature of hospitality jobs. They are more productive and disciplined than locals [4]. In that sense, some managers do not prefer to recruit local workers because they perform less compared to foreign workers [4]. However, the new Saudization quota has enforced them to employ locals; hence, they have to cope with this new quota and find effective ways to implement this new Saudization policy. They need to understand the needs of their new workers and recognize that they are different from foreign workers. Managers have to find an effective approach to deal with their new workers after properly understanding their perceptions and attitudes toward a career in restaurants/cafés, which the current study attempts to highlight.

The current study aims to compare Saudi workers’ perceptions, commitment, and attitudes toward a career in restaurants/cafés with foreign workers. To the best knowledge of the research team there are no published studies that extensively examine the perceptions, attitudes, and commitment toward careers in restaurants/cafés among new local workers, such as the case of KSA. Earlier studies on the KSA context, for example [3,4,5,6,7,8], have not examined the perceptions of new local workers compared to their foreign colleagues; however, they highlighted the effect of Saudization policy on workers and major challenges that face the private sector, including the tourism and hospitality industry. In addition, there were no published studies after the new Saudization quota in 2021, despite the major workface transformation that happened in restaurants/cafés. Furthermore, studies on perceptions and attitudes toward careers in hospitality and tourism were undertaken on students in hospitality and tourism programs [11,12,13]. Limited, if any, studies examined perceptions and attitudes of new workers toward their career in the hospitality industry, particularly restaurants. Hence, the current study fulfills a gap in knowledge in relation to the perceptions, commitment, and attitudes of Saudi workers toward a career in restaurants and cafés, post the adoption of new Saudization policy in KSA.

Examining workers’ perceptions, attitudes and commitment to a career is important because, ensuring positive attitudes and commitment towards a career is crucial for the success of any business, especially in the service industry, such as restaurants/cafés, since this influences customer satisfaction [14]. There is no opportunity for restaurants/cafés to ensure their customer satisfaction and loyalty without making sure that their workers have a positive attitude toward their work [14]. This is becoming ever more obvious as organizations use their workers to obtain a competitive edge over their competitors [15]. The degree to which an employee is committed to any sector depends on his/her attitude and perceptions about working in that sector [16]. In addition, workers’ attitudes toward their career affects workers’ job satisfaction, job performance and overall organizational success [16]. Hence, the current research has several managerial and theoretical implications, especially in relation to new entrants to a restaurant/café career, which also has implications for a sustainable tourism and hospitality industry.

In order to achieve the study objectives, a deep examination was conducted through investigation of six main issues, namely: nature of the work; social status; working conditions; career advancement; manager and relationship with team; commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés. These six main issues were drawn from Richardson [12] and were more inclusive of understanding workers’ perceptions, attitudes and commitment toward careers in the industry [13] than previous studies [3,4,11], which examined only some of these factors. This research examines the six issues among new local workers and undertakes a comparison with foreign workers. The guiding research questions (RQ) for this research were as follows:

RQ 1.

What are the perceptions, commitment and attitudes toward careers of new Saudi workers in restaurants/cafés?

RQ 2.

What are the perceptions, commitment and attitudes toward careers of foreign workers in restaurants/cafés?

RQ 3.

Is there difference in the perceptions, commitment and attitudes toward restaurant careers between local and foreign workers?

RQ 4.

What are the interventions that restaurants/cafés should undertake to ensure effective implementation of the new Saudization policy?

In order to achieve the study objective and answer the research questions, the breakdown of the remaining sections of the manuscript is as follows. Section 2 reviews the available related literature concerning workers’ perceptions of careers in restaurants, especially in a Saudi context whenever possible in relation to six main issues: nature of the work; social status; working conditions; career advancement; manager and relationship with team; commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés. Section 3 presents the quantitative method used for data collection and analysis. Consequently, Section 3 shows the statistical results of the study. The results are discussed in Section 4 and compared with earlier related studies. Section 5 presents the study implications. The study’s conclusions and limitations are presented in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Nature of Work

The hospitality industry, including the restaurant sector, is characterized as a low-paid job compared to other service industries [17,18]. This low level of payment influences the quality of work and dissatisfaction of employees, further to its impact on turnover [19]. It negatively affects workers’ job satisfaction [16]. Furthermore, the food service sector is usually classified as having unsocial working hours, such as nightshifts, weekends, split shifts, and working on holidays [18]. These working arrangements could cause additional stress for restaurant/café workers who have family obligations, especially for women who take care of children or elderly relatives [20,21]. In an Egyptian context, Sobaih [18] claimed that skill shortages push hospitality managers to employ workers without the required skills or qualifications to fill in their jobs. However, employers are unwilling to spend money in training unless they are obligated to achieve the legal requirements, because they consider the benefits of staff training and development are unlikely to be recovered [22]. Therefore, restaurants and cafés have a negative reputation for career advancement and training opportunities [10,20].

In the context of KSA hospitality employment, Sadi and Henderson [4] asserted that foreign workers are willing to accept a lower salary compared to local worker. This is unsurprising because workers in KSA hospitality are from developing countries with a good exchange rate compared to the Saudi Riyal, such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines, or Egypt. They could accept less salary compared to locals because such salaries are often better than their home countries. In that sense, Bailey [21] argued that in general immigrant workers often paid less than local workers did. Cooper [23] claimed that new local workers asked for about six times the salary of qualified immigrants [24]. Furthermore, expatriates are willing to adapt their life to fit with job requirements in the tourism industry [3,25]. The majority of foreign staff in GCC countries, including KSA, are young males who have immigrated from developing countries; hence, they accepted a lower wage because they still earn better than they earn in their home country [26,27]. Additionally, local workers have a bad image of cafés/restaurants as a career associated with poor work status and high job stress, which might affect their mental health [28]. Hence, they do not continue at this occupation for a long time compared to foreign employees [4], because they prefer jobs in public sectors, since these offer better working conditions than the private sector, such as hotels [3].

2.2. Social Status

It is important that the selected workers have to fit a restaurant job. Person–job fit is the degree to which an employee’s knowledge, skills, interests, and attitudes align with the demands of their position [29]. Earlier studies on Saudization, e.g., [3,30] showed that Saudis prefer to join the public sector than private sector because it offers more job opportunities and proper social status. In this sense, Baki [31] asserted that social status is the key factor when selecting a certain type of job among Saudis. Additionally, Saudis prefer to avoid an entry-level job and select a career with managerial levels post their graduation, or at least an office job. Likewise, Ramady [32] indicated that social status among Saudis is a key factor to accept or to reject a certain type of occupation as it affects social relationships with others in the community. Furthermore, Saudi youth are less likely to join a job that requires physical activities and/or a career with a poor reputation according to Saudi culture, such as restaurants/cafés [3,4,33]. Similarly, Tayeh and Mustafa [25] reported that Saudi youth have common cultural and social norms, which is reflected in their limited motivation and reticence to work in certain careers, such as restaurants/cafés, because they often view these as bad jobs.

According to Mahdi and Barrientos [34], employers in KSA were anxious about hiring a significant number of local workers, because they believed that it could lead to inefficiencies of team and potentially even cause a company to collapse. Al-Dosary and Rahman [33] noted that Saudization has negatively influenced the private sector’s productivity because most occupations do fit with the requirements of local workers, albeit employers have to cope with localization policy and hire a certain proportion of local workers. Another challenge to social status among Saudis is the job salary, as Sadi and Henderson [4], indicated that there was also concern that small and medium-sized businesses, such as restaurants and cafés, would struggle to meet salary expectations of Saudis in these occupations. Managers are concerned that this would raise their financial costs and affect their business growth.

2.3. Working Conditions

Previous studies, e.g., [35,36] in the tourism and hospitality context have shown that they have poor working conditions, unsociable and long working hours, stressful situations, and lack of family life. Likewise, Azhar et al. [3] confirmed that number of working hours in Saudi hotels were longer than those in governmental or public sector jobs. Additionally, Scott-Jackson and Scott-Jackson [37] argued that flexible and part-time employment arrangements are uncommon in KSA. Additionally, local workers have perceptions that the private sector has a lower level of job security compared to public sector [3]. Nevertheless, this perception of job insecurity in the private sector may not exist in KSA, because of strict procedures regarding the termination of national workers, whether in the public or private sectors [38].

Workers in the Saudi public sector enjoy more holidays, e.g., public holidays, compared to the private sector; thus, they prefer to avoid a hospitality career for limited holidays [3]. Undoubtedly, there is a difference in working conditions in the public and private sectors; hence, Saudis do not favor the private sector, particularly in small and medium-sized businesses [3]. The public sector offers a long-term career with clear advantages and pensions [5]. Managers believe that the local workers lack flexibility and are poorly adapted to the working conditions in the industry [39].

2.4. Career Advancement

The hospitality industry has minimal opportunities for promotions and a career path [14,40]. Lashley [10] claimed that food service outlets do not have a good reputation concerning opportunities for training and career advancement. Earlier studies, e.g., [10,19,41] indicated that there is a lack of formal training programs in hospitality, and many restaurants operate without training and development programs. In the context of KSA, it has been proven that Saudis prefer to work in the public sector over the private sector since it offers them regular opportunities for promotion to managerial level with less effort than the private sector [42]. Likewise, Assiri [43] reported that Saudis do not prefer to work in hospitality because it lacks good promotion opportunities. Similarly, previous studies, e.g., [43,44] argued that collectivist societies, such as KSA, may place more emphasis on tangible results, such as promotion opportunities and salaries, when selecting their career. Harbi et al. [45] claimed that in KSA, nepotism, also called “Wasta”, is one of the drivers for workers’ recruitment and promotion rather than performance appraisal outcomes.

Despite the recent growth in the KSA tourism and hospitality industry, which creates significant job opportunities, Saudis do not really believe in a serious career opportunity in hotels and similar sectors, such as restaurants [3]. Patrick [46] claimed that neither the education programs nor the dominant culture in Saudi Arabia prioritize the development of soft skills. As a result, a scarcity of necessary skills has been noted as a problem in the implementation of the Saudization policy and affects Saudi promotion opportunities. Hence, Al-Munajjed and Sabbagh [47] confirmed that private employers view expatriates as more valued than Saudis, who should undertake training to develop their skills. This lack of skills among new entrants in the private sector, such as restaurants, could be bridged by providing proper training opportunities.

2.5. Manager and Relationship with Team

According to Baqadir [48], the majority of managers in the private sector consider Saudi workers as unreliable and lazy. While the private sectors are obliged to apply the Saudization policy to avoid the Saudi government penalty, this has led to widespread hiring of “Ghost Workers” in the private sector, who are employed but do not actually work [42]. According to this practice, one of the foreign workers will perform the duties instead of them, which increases their workload. However, the performance of the team, and ultimately the performance of the organization, might be badly impacted by this approach [49]. Additionally, Ramady [32] confirmed that local employees are concerned about their integration into multicultural workplaces because of concerns that it could diminish their status. By the same thinking, earlier studies, e.g., [27,50] confirmed that national employees struggle to adapt to the multicultural workplace environment. Certainly, these types of practices have a negative impact on team spirit, team cooperation and team performance [16]. On the contrary, managers can enhance employee commitment to the company by building a good relationship and encourage better communication with their peers [51].

2.6. Commitment to Career

A worker’s commitment to a career is affected by his/her perceptions and attitude toward working in the industry [13]. Positive employee attitude is crucial to ensuring commitment to a job, which has an impact on team performance [14]. A person’s career decision is influenced by his/her own “self-interests” [52]. Interest can be defined as “the individual’s motivation to do whatever it takes to satisfy their own desires” [53] (p. 1152). El-dief and El-dief [11] added that selecting a career based on interests is closely related to job satisfaction. Career outcome expectation is an important variable related to commitment to a career [54]. However, restaurant/café work is characterized by lack of family life, long and unsociable working hours, poor physical working conditions, stressful situations, and low skill requirement [35,36,37,55]. These characteristics of food service outlets affect negatively on a worker’s commitment to a career [55]. Supervisor’s respect and encouragement contribute to an effective working environment [13]. Furthermore, poor social status is one of the main obstacles to applying localization policy in restaurants and cafés in KSA and enhances commitment to a career [11]. Barnett et al. [56] have asserted that social status has both collective and individual aspects because it influences one’s social and career relationships as well as how his or her family perceived this.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection Methods and Procedures

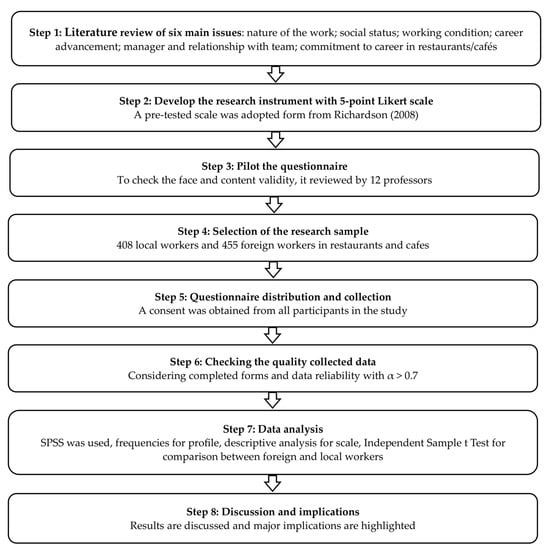

The research has support from a company specialized in data collection for research purposes to collect quality data. The researchers were responsible for ensuring that the research process was undertaken properly, such as describing the research purpose for the participants and gaining their consent to participate in the study. The company facilitated the communication with restaurant/café managers to access their staff for the research study. Following the approval of managers, workers were accessed before the beginning of their shift or during their break to explain the purpose of the study and obtain their consent to participate in the study. After their consent, they were asked to fill in the questionnaire form. One of the research team was present at all stages of the data collection process. The full research process, including the data collection and analysis stage, is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research process [12].

The questionnaire form contained sections. Section 1 asked respondents about their gender, age, educational level, job position, monthly income, working experience and working hours. Section 2 asked respondents about the nature of their work. An example of the items is “jobs in restaurants/cafés are interesting”. Section 3 asked workers about social status of their restaurant/café job. An example of the items is “restaurant/café is a respected vocation”. Section 4 asked workers about working conditions. An example of the items is “working conditions are generally good”. Section 5 asked workers about career advancement. An example of the items is “Promotion opportunities are satisfactory”. Section 6 asked workers about relationship with their manager and team members. An example of the items is “Managers behave respectfully toward employees”. Section 7 asked workers about their commitment to a career in restaurants and cafés. An example of the items is “I would recommend restaurants/cafés jobs to friends and relatives”. Sections 2–7 asked respondents, whether foreigner or local, to state their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). The research adopted pre-tested scale items. These items (in Sections 2–7) were obtained from Richardson [12]. Section 8 asked respondents to add any further comments (if they want) about their job in restaurants/cafés.

The questionnaire was piloted with 12 professors of management to check the face and content validity. There was minor editing of questions. For example, the term “H&T” in the original scale was replaced with restaurants/cafés. Data were collected during November 2022 after one year of the new quota in restaurants/cafés. It is worth mentioning that there was difficulty in data collection from local workers due to their actual limited proportion in food preparation and service.

3.2. Population and Sample

The population of this research includes all workers in restaurants and cafés. Recent statistics (the General Authority for Statistics 2021) [57] confirm that there are 451,999 workers in food service outlets. This number includes both local and foreign workers in restaurants and cafés. The sample size of the current research is in line with the proposition of Krejcie and Morgan [58], who suggested that the sample of this population size should be 384 participants or above. Since the population is divided into two groups: local and foreign workers, there should be 384 from each group. This research has a sample of 408 local worker and 455 foreign workers, totaling 863 participants. This sample size is also satisfactory according to Roussel [59], who argued that the sample size has to be 5 to 10 times the items adopted in the research. This research has 49 items, and the sample should be between 245 and 490 participants. Additionally, the sample meets the suggestion of Taherdoost [60], who confirmed a sample of 384 participants for population of 500,000 up to 1,000,000 with a confidence level = 95% and 660 participants for population of 500,000 up to 1,000,000 with a confidence level = 99%. The sample size of current research meets these requirements.

3.3. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using computer software Statistical Package in Social Science (SPSS) version 26. The research adopted frequencies and percentages to analyze the profile of respondents. Descriptive statistics (i.e., minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation) were adopted to analyze the Likert scale and understand perceptions, attitudes, and commitment towards a career in restaurants and cafés. Independent sample t-test was adopted to compare between local and foreign workers.

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Profiles

Table 1 shows a summary of the respondents’ profiles. As expected, and based on Saudi culture and food service nature, the majority of participants were male, with a low proportion of Saudi females (19.6%) compared to foreign females (32.3). The vast majority of respondents were less than 40 years old, as 74% of both local and foreign respondents were aged between 18 and 40 years old. Foreign respondents were more educated than local respondents as the majority of them, 72.3%, had university degrees and the rest had diplomas, whereas none of local workers in this research had university degrees and the vast majority hold secondary school certificate or less (about 91%), see Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondents’ profiles.

The position of both local and foreign workers varies. Local workers were found in frontline jobs, such as welcoming customers (47.1%), whereas foreign workers were found more frequently in food preparation (40%) than foodservice. There was no cashier position among foreign workers as this job was dominated by local workers. With regard to the monthly salary of participants, local workers were found to receive higher salaries than foreign workers do. Despite about 37% of foreign workers being supervisors, their salary did not exceed SAR 10,000; whereas, about 16% of local workers received a monthly salary over SAR 10,000. This is despite these local workers having less than one year in a restaurant career. Of them, 57% had less than 6 months of experience. These workers were the response of restaurants and cafés to the new quota implemented in October 2021. However, all foreign workers had above 2 years of experience. Several foreign workers commented they have over 10 years of experience in restaurants. There were also differences between working hours for local and foreign workers. Foreign workers were found to work notably more hours than local workers, as 40% of foreign workers were found to work more than 60 h a week and 43.1% working between 51 and 60 h a week, whereas none of the local workers were working above 50 h a week. The vast majority of local workers, 80.4%, work 40 h a week or less.

4.2. Nature of the Work

Table 2 shows the perceptions of local versus foreign workers in relation to the nature of their work in restaurants/cafés. While local workers disagreed that their jobs in restaurants/cafés are interesting (M = 2.04; SD = 0.76), foreign workers agreed these jobs are interesting (M = 4.32; SD = 0.55). Furthermore, local workers agreed that their jobs in restaurants/cafés are low skilled (M = 4.47; SD = 0.61), stressful (M = 4.33; SD = 0.62), working hours are too long (M = 4.27; SD = 0.60) and unsuitable (M = 4.37; SD = 0.48), and negatively affected their family life (M = 4.39; SD = 0.63). On the other side, foreign workers disagreed that their jobs in restaurants/cafés are low skilled (M = 1.54; SD = 0.61), and working hours are too long (M = 1.38; SD = 0.49) and unsuitable (M = 2.07; SD = 0.66). Despite foreign workers working more hours than local workers, they did not argue that this negatively affect their family life (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceptions of the nature of working in restaurants/cafés.

4.3. Social Status and Person–Job Fit

As Table 3 shows, there is variance between local and foreign workers’ perceptions of their social status with restaurant/café jobs. For instance, foreign workers agreed that their families are proud of their jobs in restaurants (M = 4.52; SD = 0.64), whereas local workers disagreed with this perception (M = 1.27; SD = 0.45). Therefore, foreign workers consider that restaurant work is a respected vocation (M = 4.38; SD = 0.63) and an important job (M = 4.52; SD = 0.61), whereas local workers have a negative view of the restaurant/café vocation (M = 1.45; SD = 0.54) and its importance (M = 2.11; SD = 0.68). Local workers agreed that working in a restaurant is not valued (M = 4.35; SD = 0.48), because they feel like a slave working in restaurants (M = 4.43; SD = 0.63). In contrast, foreign workers disagreed with these claims. While foreign workers believe they can use their skills and abilities in these jobs and like to see their customer satisfied, local workers disagreed that their character fits with the industry nor can they use their skills and abilities in these jobs.

Table 3.

Perceptions of social status.

4.4. Working Conditions

Respondents’ perceptions of working conditions are shown in Table 4. While local workers disagreed that their working conditions are good (M = 1.47; SD = 0.50), foreign workers rated working conditions as very good (M = 4.49; SD = 0.50). Furthermore, local workers agreed that working environment is not very clean (M = 4.25; SD = 0.62), risky (M = 4.41; SD = 0.57), noisy (M = 4.27; SD = 0.69), has a low salary (M = 4.47; SD = 0.50) and the level of fringe benefits is low (M = 4.43; SD = 0.50). On the contrary, foreign worker disagreed with local workers’ perceptions and found the working environment clean (M = 1.60; SD = 0.55) and appropriate (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Perceptions of working conditions.

4.5. Career Advancement

Table 5 presents local and foreign workers’ views of career advancements in restaurants/cafés. The results showed that local workers have negative views of promotion opportunities in restaurants/cafés (M = 1.80; SD = 0.66) and consider the promotion as not handled fairly (M = 3.98; SD = 0.83). Nonetheless, foreign workers are satisfied with job promotion opportunities (M = 4.22; SD = 0.73), and they disagreed that job promotion is not handled fairly (M = 1.75; SD = 0.63). Therefore, local workers believe that the opportunity to be promoted to a management position is limited (M = 4.47; SD = 0.50), their academic qualifications are considered (M = 4.17; SD = 0.79), and they claim that there is a lack of clear career paths introduced by industry (M = 4.17; SD = 0.79). However, foreign workers have a positive view regarding management promotions, academic qualifications and career paths offered by the industry, despite how they hold higher qualifications and experience compared to local workers.

Table 5.

Perceptions of career advancement.

4.6. Relationship with Manager and Team Members

The participants’ perceptions of their coworkers and their relationship with managers are provided in Table 6. The results showed that local workers agreed there is no team spirit among restaurant/café team members (M = 4.12; SD = 0.68) and they are unmotivated (M = 1.3; SD = 0.48). Foreign workers disagreed with those perceptions regarding team spirit (M = 1.46; SD = 0.50) and they feel motivated in their job (M = 4.12; SD = 0.62). Furthermore, local workers have negative perceptions about relationships with their manager in some issues, such as authority delegation (M = 1.47; SD = 0.50), and engagement decision making (M = 1.59; SD = 0.69). Foreign workers have a better perception than local workers in the same points, authority delegations (M = 4.27; SD = 0.71), and decision-making (M = 4.17; SD = 0.69). Both local and foreign workers have the same opinion regarding poor relationships between managers and staff; further, both sets of workers are unhappy with manager efforts to ensure staff satisfaction.

Table 6.

Relationship with manager and team.

4.7. Commitment to Career in Restaurants/Cafés

According to Table 7, local workers show limited, if any, commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés. For example, local workers see disadvantages of working in restaurants/cafés outweigh advantages (M = 4.49; SD = 0.50) and they are unlikely to select restaurant careers for their child, whether for studying or working (M = 4.69; SD = 0.46). In contrast, foreign workers disagreed with earlier perceptions of local workers. Additionally, local workers are unhappy with their chosen restaurant career (M = 1.43; SD = 0.5), unlikely to continue in a restaurant/café career (M = 1.29; SD = 0.46), and do not see their career in restaurants (M = 1.35; SD = 0.48); consequently, they would not recommend a restaurant career to their friends (M = 1.35; SD = 0.48). Foreign workers hold different perceptions to local workers, since they are happy with a restaurant/café career (M = 4.48; SD = 0.56), prefer to continue in the same career (M = 4.51; SD = 0.56), and they see their career in the restaurant industry (M = 4.29; SD = 0.65); hence, they would recommend that career for their relatives and friends (M = 4.48; SD = 0.56).

Table 7.

Commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés.

4.8. A Comparison between Local and Foreign Workers

As it could be seen from the data in Table 8, there are statistically significant differences between local and foreign workers’ perceptions, attitudes, and commitment to careers in restaurants/cafés in relation to the six dimensions investigated. These include nature of work (t = 91, 17 p < 0.001), social status (t = −136, 74 p < 0.001), working condition (t = 81, 04 p < 0.001), career advancement (t = 48, 43 p < 0.001), relationship with manager and team (t = −2, 15 p < 0.05), and commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés (t = −69, 47 p < 0.001). Foreign workers tend to hold positive perceptions, attitudes and commitment to a career compared to local workers, who showed negative perceptions, attitudes, and commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés.

Table 8.

A comparison between local and foreign workers.

5. Discussion

This research is a response to the recent Saudization quota, which took place in October 2021 in restaurants/cafés. The new policy enforced restaurants/cafés to employ a proportion of local worker, ranging between 20% and 50% based on the location of the restaurant/café (outside or inside shopping mall/centers, respectively). This research examines the new local workers’ perceptions, attitudes, and commitment toward a career in restaurants/cafés and compares this with their foreign colleagues after the new Saudization quota. The results confirmed statistically significant differences between local and foreign workers’ perceptions, attitudes, and commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés in relation to the six dimensions investigated: nature of work, social status, working conditions, career development, relationship with managers and co-workers, as well as commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés.

With regard to the first dimension “nature of work”, the results indicated significant differences between local and foreign workers. More exactly, the results confirmed that Saudis have negative perceptions toward their work in restaurants/cafés. However, this negative perception of the work would certainly influence their work attitude and behavior [11,16]. It could negatively affect their mental health and job performance [16]. They agreed that their restaurant job is not interesting, low skilled, stressful, has unsuitable working hours and negatively affects their family life. These results are agreement with the findings of earlier studies in relation to the poor perceptions held by local workers of the hospitality industry in KSA pre the current new quota [3,4]. On the other side, foreign workers were found to hold positive perceptions regarding the nature of work in restaurants/cafés. They evaluated restaurant job as interesting, high skilled, having suitable working hours and stable employment. These results support the work of Tayeh and Mustafa [25] and Azhar et al. [3] that expatriates in the Saudi hospitality industry held more positive perceptions of their job than their local counterparts.

The findings indicated a significant difference between local workers and foreign workers in relation to perceptions of social status of working in restaurants/cafés. According to Tayeh and Mustafa [25] and Al-Dosary and Rahman [33], Saudis hold destructive cultural and social norms about working in service jobs, such as restaurants and cafés. The current research confirms that local workers perceived restaurant/café jobs as a “servile job” and they feel like a “slave” when they joined their jobs at restaurants/cafés. Saudis do not accept this servile nature of jobs offered in restaurants/café. Due to the poor image of restaurant/café jobs among Saudis, the newly joined workers suffer from work “stigma”, believing that they are at a minimal job that is not respected by their local community. They feel a low job status among their community. Hence, this is reflected in their poor motivation and reticence to continue in such jobs. This is confirmed by their responses when they disagreed that restaurant/café jobs are a respected vocation, valued, beneficial/important and pleasant. Additionally, they feel that their family is not proud of a restaurant/café job and their character does not fit with such job. Hence, they are not proud of their job nor with their career. This low image and job status negatively affects their job outcomes and the overall organizational outcomes, making a threat to the sustainable performance of the organization. On the contrary, foreign workers who are more educated and experienced were found to be proud, happy with a restaurant job and their career. They considered restaurant job as a valuable vocation, important, beneficial, and fit with their character. This could be because they view such jobs as good for them and for the society. This positive view of the job positively effects workers’ job satisfaction and their performance [15,16].

Local workers were found have negative perceptions of working condition in restaurants/cafés. This is because they compare restaurant jobs with other jobs in the private sector or public sector. In general, jobs in the hospitality industry are stressful, with long and unsocial working hours to meet customer needs [13,35,36]. However, the situation in restaurants/cafés from the perceptions of Saudis was even worse as they indicated that working environments are generally not good, not clean, risky, noisy, with low benefits and salary level. The new Saudi workers that joined restaurants/cafés rated the working conditions of their jobs as very poor because they often compare them with the office jobs in the public sector. This gap between restaurant/café jobs and public sector jobs made it difficult for new workers to accept either their new jobs or working conditions. On the other side, the results, obviously, indicated significant differences between local and foreign workers regarding working conditions. Foreign workers were found to be satisfied with working conditions and considered their working environment as clean, with a good chance of a suitable salary and benefits, despite being paid less compared to their local colleagues. This finding is in agreement with previous work of Sadi and Henderson [4] and Azhar et al. [3], who found that local workers in hospitality were less satisfied with their working environment compared to foreign colleagues. Hence, Aldosari [39] indicated that employers preferred to recruit non-Saudis because they believe that local workers lack flexibility and poorly adapt to the working conditions in restaurants/cafés.

The results also showed that Saudi workers were unhappy with promotion process and considered promotion to managerial positions limited and not handled in a fair way. Nonetheless, Saudis put more emphasis on promotion opportunities when they select a career [42,44]. Additionally, they prefer the public sector than private sector because they claim that the public sector provides a regular opportunity for promotion to managerial level [42]. Furthermore, Sadi and Henderson [4] argued that local workers preferred the government and/or public sector due to career advancement opportunities. Another major challenge in restaurants/cafés is they are mostly small and offer less career advancement opportunities. Hence, Saudis do prefer to join the job, because they expect less opportunity for advancement. On the other side, foreign workers showed a high level of agreement regarding promotion opportunities, fairness of promotion and their career path in restaurants/cafés.

The results indicated significant differences between perceptions of local workers and foreign workers with regard to their relationship with managers and other team members. Local workers do not feel spirits of team, cooperation or a friendship with other team members. This feeling of Saudi workers is a result of their poor perceptions of working environment, which could lead to negative attitudes toward their career [14,15]. Hence, they view their job as “temporary” and not as a long life career. Some of them are “Ghost Workers”, who are paid but do not actually work; hence, foreign workers undertake their duties, which could increase their workload and destroy team spirit [49]. The negative view about team spirit held by local workers could be because of negative perceptions they held about the job and its nature. Additionally, the results confirmed that local workers have negative perceptions toward their relationship with their managers, who are mostly foreigners. Managers could respond with negative perceptions of local workers; hence, Baqadir [48] argued that the majority of managers in the private sector considered Saudi workers as unreliable and lazy. On the other side, the results of the current research showed that foreign workers have positive perceptions toward relationships with other team members or with their managers. Foreign workers were found to have a positive view of the job and the team because they feel that their team has a spirit of team members.

Concerning issue six, which is commitment to a career in restaurants/cafés, the results showed that local workers reported a lower level of commitment toward their job and career in restaurants/cafés compared to their foreign colleagues. As highlighted earlier, local workers were found to have negative perceptions of restaurant/café jobs, working conditions, career advancement, social status and relationships with their team members and manager; hence, they were found to be unhappy with their work and dislike restaurant careers. This means that all of these issues are related to each other and contribute to the limited commitment to careers in restaurants/cafés among Saudis. Therefore, they would not recommend restaurants/cafés to their sons or/and relatives. This finding is supported by earlier research results, e.g., [3,4,11] about the poor social status related to service jobs in hospitality with poor working conditions, such as low level of salary, as the main obstacles to adopting commitment among Saudi workers in restaurants/cafés. In contrast, the results showed that foreign workers are committed to restaurant careers and view them as long-life careers, which impacts on their job attitude and behavior [15,16]. This could be one of the reasons why many employers in the private sector in KSA view foreign workers as more reliable than foreign workers.

6. Implications of the Research

The study findings have enormous implications for scholars and restaurant/café administrators and decision makers. The negative perceptions of restaurant/café jobs among local workers, who are new to such jobs, is mainly due to cultural factors and social norms among Saudi that view restaurant/café jobs as unimportant, not valued in society, and not a respected vocation. Local workers feel like slaves in their jobs. Additionally, they hold negative attitudes and commitment toward the career. As a result, they see the disadvantages of working in restaurants/cafés outweigh advantages and they would not continue in restaurants as a career nor recommend to their family members, relatives or friends. This would negatively influence their job attitudes and behavior [13]. It is therefore important that policy makers try to have a media campaign to improve the image of the sector and meet these cultural barriers to create a better social status of restaurant/café jobs, which contributes to positive attitude and behavior. Furthermore, scholars and restaurant administrators recognize the role of culture in affecting the perceptions of workers toward certain jobs. In the service industry, such as restaurants/cafés, employee attitude and behavior are important determinants of customer satisfaction and loyalty [61]. Additionally, worker satisfaction is a predictor of customer satisfaction [62]. Workers’ attitudes and behavior could make a competitive advantage [15] and have an impact on overall performance of the business [63]. Furthermore, workers’ attitudes and commitment to a career ensure positive job outcomes and contribute to sustainable performance of the team [63].

The study confirmed local workers’ perceptions, commitment, and attitudes toward a career in restaurants/cafés are poor and could be even worse than other sectors of the hotel industry, such as hotels. Significant differences were found between local and foreign workers. Hence, it is important that both scholars and restaurant managers recognize the differences between local and foreign workers. Therefore, local workers need to be treated differently to achieve better job outcomes. For example, it is important that managers understand the preferences of Saudis in relation to working days and shifts. A flexible work schedule, particularly on weekends and public holidays, should proceed. These days are important for Saudis due to family meeting on these days. Scholars, on the other side, should examine each group separately to gain better understanding of their attitudes and behavior.

The success of the new quota in the private sector relies on government support given to businesses. Small and medium-sized restaurants, as the most dominant type of restaurants [64], look for financial government support to fulfill the minimum wage in restaurants/cafés, which do not meet the needs of Saudis. There is a wage gap between private and public sectors; hence, the role of government is crucial in motivating local workers to join the private sector and bridge the wage gap with the public sector. Furthermore, media campaigns are required to raise awareness for Saudis about their contribution to society through their involvement in the private sector. The government should sponsor training programs that are provided by industry professionals in order to enhance the skills of new local workers and properly introduce them to careers in restaurants/cafés. Training programs should include both off-the-job training and on-the-job training to transmit the required skills to new workers. There is evidence that a well-designed and adequate training program increases employees’ satisfaction and their organizational commitment [65]. Additionally, restaurant managers in KSA should understand the government shift in policy toward Saudization and develop a plan for effective execution. Both vocational organizations in KSA and industry practitioners should work closely to supplement new workers with sufficient knowledge and understanding of the nature of restaurant/café work. Furthermore, since Saudi graduates seek employment at managerial levels, government should co-operate with industry partners to implement “managerial training programs,” focusing on graduates with potential to become industry leaders based on certain criteria.

7. Conclusions

KSA is one of the countries that largely relies on foreign workers, especially for jobs and careers that are not wanted by local people, such as in restaurants and cafés. However, the Saudi Vision 2030, which launched recently, aims to decrease the unemployment rate to the minimum level from 12.9% to 7% by 2030. Therefore, the government has announced a new quota for Saudization in restaurants/cafés. This study investigated local versus foreign workers’ perceptions, attitudes, and commitment towards careers in restaurants/cafés. The study was set to answer four main research questions. In response to research question number one “What are perceptions, commitment and attitude toward career of Saudi workers in restaurants/cafe?”, the results showed that local workers have a negative perception, attitude and hold low level of commitment toward a career in restaurants/cafés, mainly because of poor work image and how it hits their social status. This could have negative consequences on their work outcomes. Concerning question number two “What are perceptions, commitment and attitude toward career of foreign workers in restaurants/café?”, the study findings indicated that foreign workers have positive perceptions, attitudes, and commitment toward a career in restaurants and cafés. Therefore, the answer of question number three that states “Is there difference in the perception, commitment and attitude toward restaurant career between local and foreign workers?” is that the results confirmed significant differences between local and foreign workers’ perceptions, attitudes and commitment toward careers in restaurants/cafés. Regarding question number four “What are the interventions that restaurants should undertake to ensure effective implementation of new Saudization policy in cafe/restaurants?”, restaurant managers should develop a plan for effective execution of plans for the new quota. The plan should include a development program for developing skills of new workers. Additionally, they should offer flexible working rosters to meet Saudi worker expectations as well as business needs. Collaboration with the government is highly recommended to develop new workers and ensure effective implementation of the new quota, which requires financial support in some cases.

This study has some limitations. This research was concerned with local versus foreign worker perceptions, commitment, and attitudes toward careers in restaurants and cafés in Saudi Arabia using a self-reporting questionnaire. Therefore, the results could be limited to restaurant/café careers in Saudi Arabia. It is therefore suggested that that these results could be examined in different cultures with wider research samples. Further research could be directed to study different sectors within KSA, such as retailing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; methodology, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; software A.E.E.S.; validation, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; formal analysis, A.E.E.S.; investigation, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; resources, A.E.E.S.; data curation, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; writing—review and editing, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; visualization, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; supervision, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E.; project administration, A.E.E.S.; funding acquisition, A.E.E.S. and A.E.A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [GRANT2895].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the deanship of the scientific research ethical committee, King Faisal University (project number: GRANT2895, date of approval: 1 November 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through e-mail.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fridhi, B. The entrepreneurial intensions of Saudi Students under the kingdom’s vision 2030. J. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.; Alshallaqi, M. Impact of autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness on students’ intention to start a new venture. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A.; Duncan, P.; Edgar, D. The implementation of Saudization in the hotel industry. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. 2018, 17, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadi, M.A.; Henderson, J.C. Local versus foreign workers in the hospitality and tourism industry: A Saudi Arabian perspective. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeeh, M.S. Saudization as a Solution for Unemployment: The Case of Jeddah Western Region. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alsheikh, H.M. Current Progress in the Nationalization Programmes in Saudi Arabia; European University Institute and Gulf Research Center: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alshanbri, N.; Khalfan, M.; Maqsood, T. Nitaqat Program in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Innov. Res. Adv. Eng. 2014, 1, 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J.R. Can hiring quotas work? The effect of the Nitaqat program on the Saudi private sector. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2017, 9, 316–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRSD 2022. Decisions to Localize the Activities of Restaurants and Cafes and to Localize Supplies and Central Markets Come into Force. Available online: https://hrsd.gov.sa/ar/news/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Lashley, C. The right answers to the wrong questions? Observations on skill development and training in the United Kingdom’s hospitality sector. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dief, M.; El-Dief, G. Factors affecting undergraduates’ commitment to career choice in the hospitality sector: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 18, 93–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S. Undergraduate tourism and hospitality students attitudes toward a career in the industry: A preliminary investigation. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2008, 8, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S. Undergraduates’ perceptions of tourism and hospitality as a career choice. Int. J. Hosp. 2009, 28, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Zeithaml, V.; Bitner, M.J.; Gremler, D. Services Marketing: Integrating Customer Focus across the Firm; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J. Producing sustainable competitive advantage through the effective management of people. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1995, 9, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Carrión, R.; Navajas-Romero, V.; Casas-Rosal, J.C. Comparing working conditions and job satisfaction in hospitality workers across Europe. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102631. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, D. The quality of tourism employment. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 2129–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E. Hospitality employment issues in developing countries: The case of Egypt. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. 2015, 14, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, C.; Rawson, B. The Benefits of Training for Pub Retailers; A Research Report for the Punch Pub Company; Leeds Metropolitan University: Leeds, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaih, A.E.; Coleman, P.; Ritchie, C.; Jones, E. Part-time restaurant employee perceptions of management practices: An empirical investigation. Serv. Ind. J. 2011, 31, 1749–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.R. Immigrant and Native Workers: Contrasts and Competition; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, T. Sustainable human resource management as a driver in tourism policy and planning: A serious sin of omission? J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.L. Working hours and health. Work Stress 1996, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Arabia’s Economic Reforms Are Not Attracting Investors. The Economist. 18 December 2018. Available online: https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2018/12/22/saudi-arabiaseconomic-reforms-are-not-attracting-investors (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Tayeh, S.N.A.; Mustafa, M.H. Toward empowering the labor Saudization of tourism sector in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 1, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Najjar, B.S. Aspects of Labour Market Behaviour in an Oil Economy: A Study of Underdevelopment and Immigrant Labour in Kuwait. Ph.D. Dissertation, Durham University, Durham, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Atiyyah, H.S. Expatriate acculturation in Arab Gulf countries. J. Manag. Dev. 1996, 15, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufquin, D.; Park, J.Y.; Back, R.M.; de Souza Meira, J.V.; Hight, S.K. Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: An examination of restaurant employees during COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, J.; Farashah, A.D.; Kazemi, M. The impact of person-job fit and person-organization fit on OCB: The mediating and moderating effects of organizational commitment and psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 672–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albabtain, E. Correlates of Saudi Male and Female Students Work Values and Organizations Desirability. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baki, R. Gender-segregated education in Saudi Arabia: Its impact on social norms and the Saudi labor market. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2004, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramady, M.A. Economic Planning: History, Role and Effectiveness. In The Saudi Arabian Economy: Policies, Achievements and Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dosary, A.S.; Rahman, S.M. Saudization (localization)—A critical review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2005, 8, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhi, S.T.; Barrientos, A. Saudisation and employment in Saudi Arabia. Career Dev. Int. 2003, 8, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, S.; Deegan, J. Career progression of Irish tourism and hospitality management graduates. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2005, 17, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akış Roney, S.; Öztin, P. Career perceptions of undergraduate tourism students: A case study in Turkey. J. Hosp. Leis. Sports Tour. Educ. 2007, 6, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Jackson, J.; Scott-Jackson, W. Route Planning in the Palaeolithic? (poster). In Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, London, UK, 26–28 July 2013; pp. 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- DLA Piper. Be Alert Middle East: New Saudi Labour Law. 2015. Available online: https://www.dlapiper.com/en/uk/insights/publications/2015/06/be-alertmiddle-east-new-saudi-labour-law/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Aldosari, K.A. Saudisation in the Hospitality Industry: Management Issues and Opportunities. Ph.D. Dissertation, Victoria University, Delaware, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, L.; Guerrier, Y.; Jamieson, S.; Lashley, C.; Lockwood, A. Getting Ahead: Graduate Careers in Hospitality Management; Higher Education Funding Council for England and the Council for Hospitality Management Education: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, S.M. Recruitment and training in small firms. J. Eur. Ind. 2000, 24, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asfour, A.; Khan, S.A. Workforce localization in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Issues and challenges. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2014, 17, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiri, S.M. Exploring Perceptions toward Hotel Careers in Saudi Arabia: A Mixed Methods Study of Hospitality Graduates and Industry Workers. Ph.D. Dissertation, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1980, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbi, S.A.; Thursfield, D.; Bright, D. Culture, Wasta and perceptions of performance appraisal in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 28, 2792–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, F. Making the transition to a ‘knowledge economy’ and ‘knowledge society’: Exploring the challenges for Saudi Arabia. In Education for a Knowledge Society in Arabian Gulf Countries; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; Volume 24, pp. 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- AlMunajjed, M.; Sabbagh, K.; Insight, I.C. Youth in GCC Countries: Meeting the Challenge; Booz & Company Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baqadir, A.A. A Skills Gap between Industrial Education Output and Manufacturing Industry Labour Needs in the Private Sector in Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Asmari, M. Saudi labor force: Challenges and ambitions. JKAU Art Hum. 2008, 16, 19–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellahi, K.; Al-Hinai, S.M. Local workers in Gulf co-operation countries: Assets or liabilities? Middle East. Stud. 2000, 36, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidts, A.; Pruyn, A.T.H.; Van Riel, C.B. The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; DeFrank, R.S. Self-interest and knowledge-sharing intentions: The impacts of transformational leadership climate and HR practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, S.; Kusluvan, Z. Perceptions and attitudes of undergraduate tourism students towards working in the tourism industry in Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.S.; Mak, B.; Chen, Y. Do travel agency jobs appeal to university students? A case of tourism management students in Hong Kong. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2014, 14, 87–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.; Yandle, B.; Naufal, G. Regulation, trust, and cronyism in Middle Eastern societies: The simple economics of “wasta”. J. Socio-Econ. 2013, 44, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Authority for Statistics. Tourism Establishments Statistics for 2020. 2021; 508p. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/TRS%20ANN2020E.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, P. Méthodes de Développement d’Échelles pour Questionnaires d’Enquête. In Management des Ressources Humaines: Méthodes de Recherche en Sciences Humaines et Sociales; Roussel, P., Wacheux, F., Eds.; De Boeck Supérieur: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 245–276. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Determining sample size; how to calculate survey sample size. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Syst. 2017, 2, 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, A.M.; Kacmar, K.M.; Borchgrevink, C.P. Customer service providers’ attitudes relating to customer service and customer satisfaction in the customer-server exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurdi, B.; Alshurideh, M.; Alnaser, A. The impact of employee satisfaction on customer satisfaction: Theoretical and empirical underpinning. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3561–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Ibrahim, Y.; Gabry, G. Unlocking the black box: Psychological contract fulfillment as a mediator between HRM practices and job performance. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E. Human resource management in hospitality firms in Egypt: Does size matter? Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanzeb, K.; Rasheed, A.; Rasheed, M.F. Organizational commitment and turnover intentions: Impact of employee’s training in private sector of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Commer. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).