Evaluation of Runoff Simulation Using the Global BROOK90-R Model for Three Sub-Basins in Türkiye

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data

| Sub-Basins | Area (km2) | Elevation (m) | Monthly Average Precipitation (mm) | Climate * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Çarşamba | 153.87 | 1250–2482 | 56.48 | CSA |

| Körkün | 1440.8 | 200–3588 | 100.43 | CSA–CSB |

| Karasu | 43.95 | 1960–2890 | 36.72 | DFB |

2.2. Global Brook90 R

2.3. Performance Metrics

3. Results

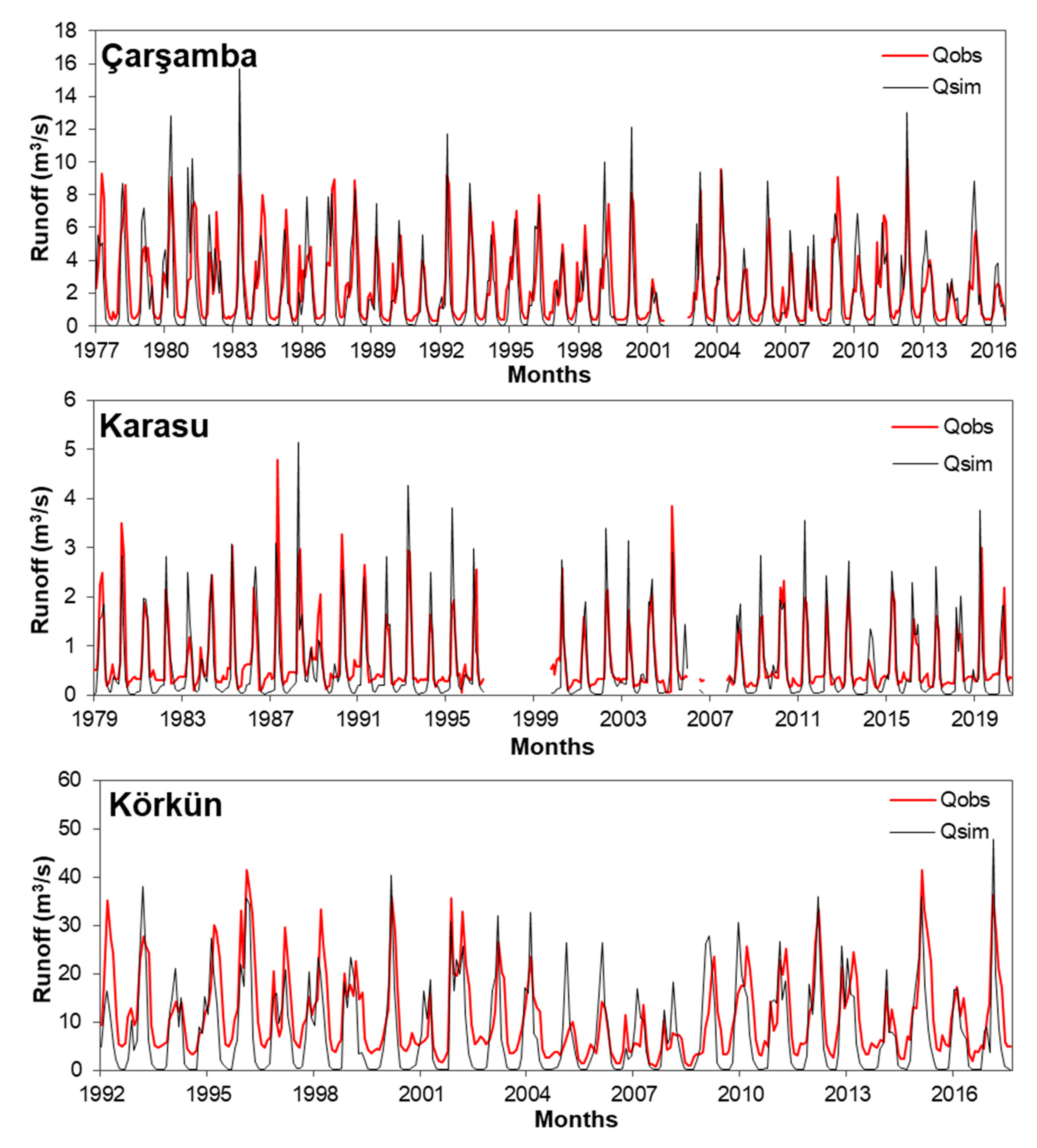

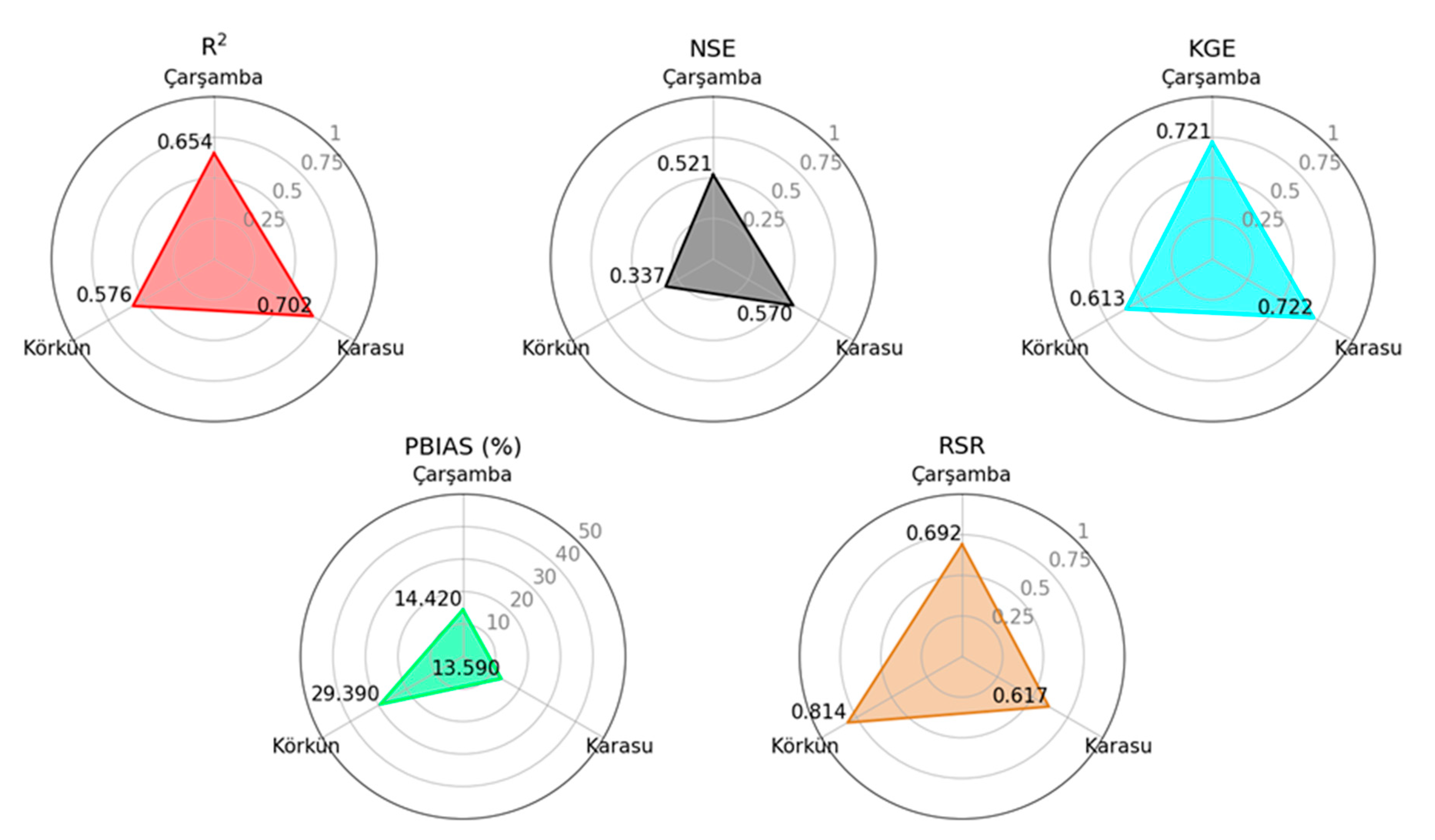

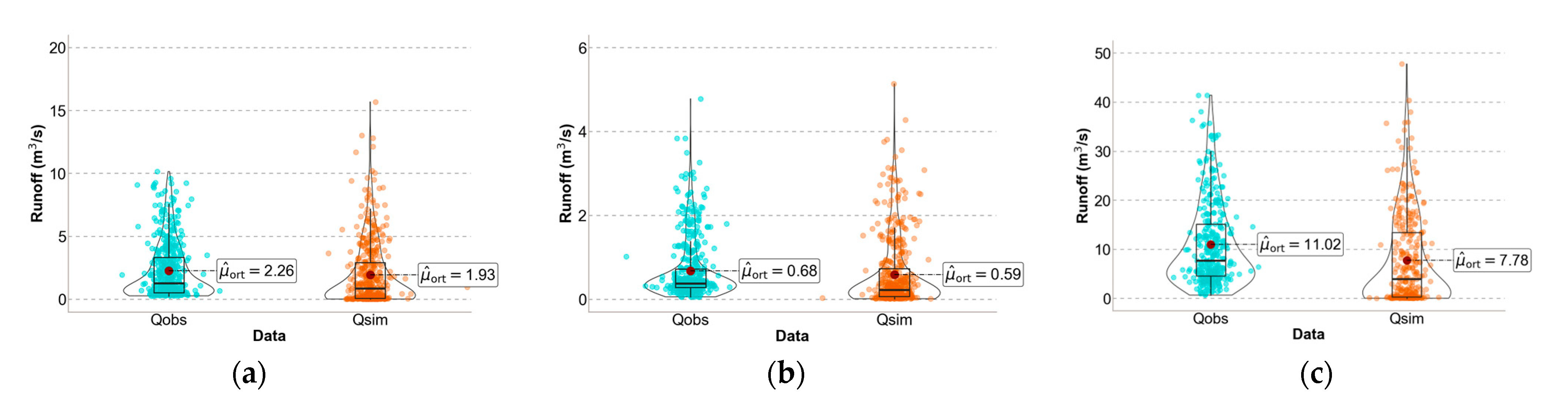

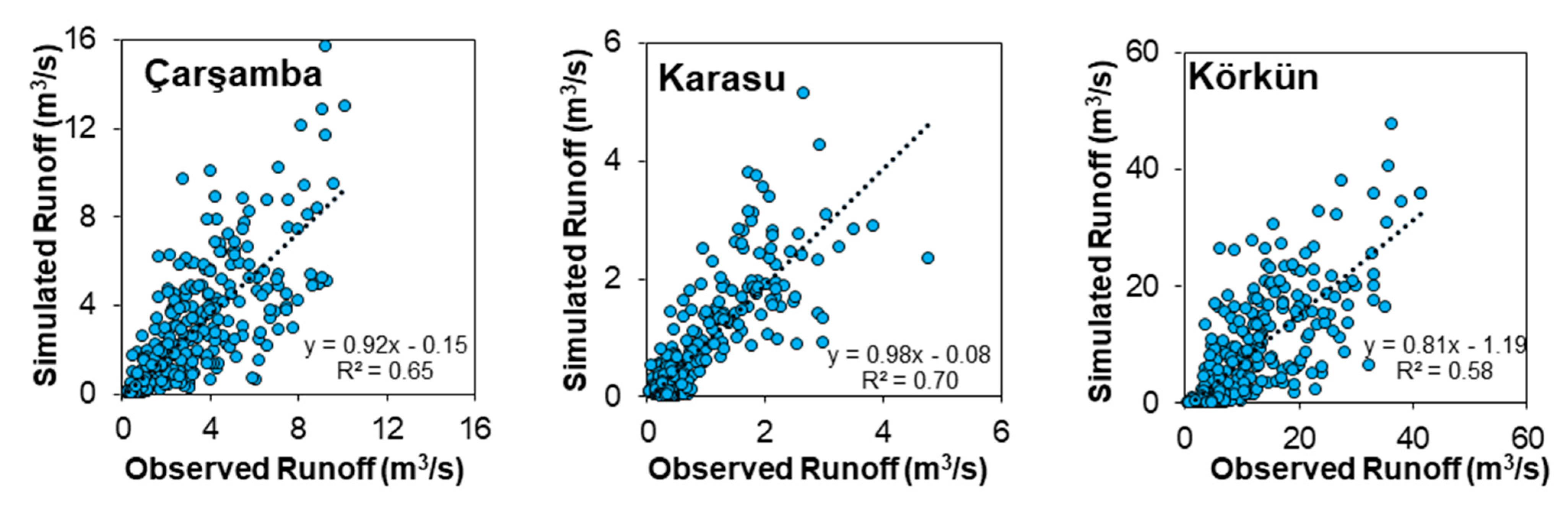

3.1. Performance of the GB90-R Model

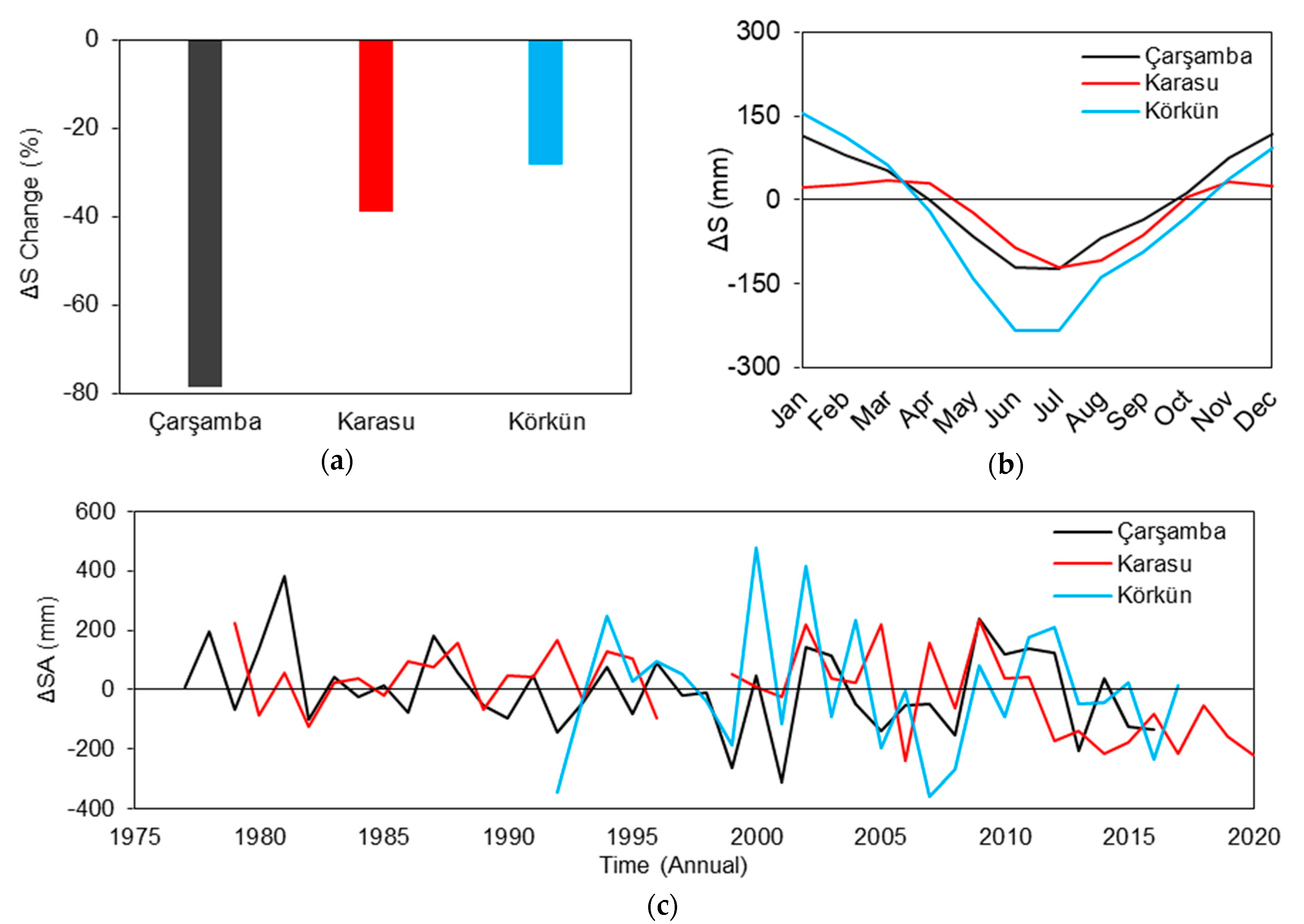

3.2. Evaluation of Water Balance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koycegiz, C.; Buyukyildiz, M. Calibration of SWAT and two data-driven models for a data-scarce mountainous headwater in semi-arid Konya closed basin. Water 2019, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koycegiz, C.; Buyukyildiz, M.; Kumcu, S.Y. Spatio-temporal analysis of sediment yield with a physically based model for a data-scarce headwater in Konya Closed Basin, Turkey. Water Supply 2021, 21, 1752–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.S.; Gill, L.W.; Pilla, F.; Basu, B. Assessment of Variations in Runoff Due to Landcover Changes Using the SWAT Model in an Urban River in Dublin, Ireland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar Basu, A.; Gill, L.W.; Pilla, F.; Basu, B. Assessment of Climate Change Impact on the Annual Maximum Flood in an Urban River in Dublin, Ireland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniconi, C.; Putti, M. Physically based modeling in catchment hydrology at 50: Survey and outlook. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 7090–7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeze, R.A.; Harlan, R.L. Blueprint for a physically-based, digitally-simulated hydrologic response model. J. Hydrol. 1969, 9, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeze, R.A. Three-Dimensional, Transient, Saturated-Unsaturated Flow in a Groundwater Basin. Water Resour. Res. 1971, 7, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeze, R.A. Role of subsurface flow in generating surface runoff: 1. Base flow contributions to channel flow. Water Resour. Res. 1972, 8, 609–623. [Google Scholar]

- Freeze, R.A. Role of subsurface flow in generating surface runoff: 2. Upstream source areas. Water Resour. Res. 1972, 8, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.B.; Bathurst, J.C.; Cunge, J.A.; O’Connell, P.E.; Rasmussen, J. An introduction to the European Hydrological System—Systeme Hydrologique European, ‘SHE’, 1: History and philosophy of a physically-based distributed modelling system. J. Hydrol. 1986, 87, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.B.; Bathurst, J.C.; Cunge, J.A.; O’Connell, P.E.; Rasmussen, J. An introduction to the European Hydrological System—Systeme Hydrologique Europeen ‘SHE’. 2: Structure of a physically based, distributed modelling system. J. Hydrol. 1986, 87, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federer, C.A. BROOK 90: A Simulation Model for Evaporation, Soil Water, and Streamflow. 2002. Available online: https://www.ecoshift.net/brook/brook90.htm (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Neff, W.H. Performance Evaluation of the BROOK Hydrologic Simulation Models on Small Central Pennsylvania Watersheds. Ph.D. Thesis, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, G.B.; David, M.B.; Shortle, W.C. A new mechanism for calcium loss in forest-floor soils. Nature 1995, 378, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, M.R.; McDonnell, J.J.; Mitchell, M.J.; Cirmo, C.P. A field-based study of soil water and groundwater nitrate release in an Adirondack forested watershed. Water Resour. Res. 2002, 38, 2-1–2-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combalicer, E.A.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, S.; Yeob, D.K.; Im, S. Modeling water balance for the small-forested watershed in Korea. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2008, 12, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panferov, O.; Doering, C.; Rauch, E.; Sogachev, A.; Ahrends, B. Feedbacks of windthrow for Norway spruce and Scots pine stands under changing climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 045019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencoková, A.; Kram, P.; Hruška, J. Future climate and changes in flow patterns in Czech headwater catchments. Clim. Res. 2011, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; McConnell, C.; James, A.; Fu, C. Comparing and Modifying Eight Empirical Models of Snowmelt Using Data from Harp Experimental Station in Central Ontario. Br. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremsa, J.; Křeček, J.; Kubin, E. Comparing the impacts of mature spruce forests and grasslands on snow melt, water resource recharge, and run-off in the northern boreal environment. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2015, 3, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuttleworth, W.J.; Wallace, J.S. Evaporation from sparse crops-An energy combination theory. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1985, 111, 839–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaetzl, R.J.; Luehmann, M.D.; Rothstein, D. Pulses of podzolization: The relative importance of spring snowmelt, summer storms, and fall rains on Spodosol development. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2015, 79, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhar, U. Water Regulation Ecosystem Services Following Gap Formation in Fir-Beech Forests in the Dinaric Karst. Forests 2021, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, M.; Seegert, J.; Feger, K.H. Effects of changes in tree species composition on water flow dynamics–Model applications and their limitations. Plant Soil 2004, 264, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federer, C.A.; Vörösmarty, C.; Fekete, B. Sensitivity of annual evaporation to soil and root properties in two models of contrasting complexity. J. Hydrometeorol. 2003, 4, 1276–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahren, A.; Schwärzel, K.; Feger, K.H.; Münch, A.; Dittrich, I. Identification and model-based assessment of the potential water retention caused by land-use changes. Adv. Geosci. 2007, 11, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, H.E.; Lopes, V.L. Simulating Soil MoistureChange in a Semiarid Rangeland Watershed With a Process-Based Water-Balance Model. In Proceedings of the Conference on Land Stewardship in the 21st Century: The Contributions of Watershed Management, Tucson, AZ, USA, 13–16 March 2000; Ffolliott, P., Baker, M.B., Jr., Eds.; U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ft. Collins, CO, USA, 2000; pp. 316–320, RMRS P-13. [Google Scholar]

- Vilhar, U. Comparison of drought stress indices in beech forests: A modelling study. iFor.-Biogeosci. For. 2016, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellpott, A.; Imbery, F.; Schindler, D.; Mayer, H. Simulation of drought for a Scots pine forest (Pinus sylvestris L.) in the southern upper Rhine plain. Meteorol. Z. 2005, 14, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, O.; Luong, T.T.; Bernhofer, C. Projected Changes in the Water Budget for Eastern Colombia Due to Climate Change. Water 2019, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffrath, D.; Vetter, S.H.; Bernhofer, C. Spatial precipitation and evapotranspiration in the typical steppe of Inner Mongolia, China—A model based approach using MODIS data. J. Arid. Environ. 2012, 88, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candaş, A. Reconstruction of the Paleoclimate on Dedegöl Mountain with Paleoglacial Records and Numerical Ice Flow Models. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg, R.; Oehlschlägel, L.M.; Bernhofer, C.; Luong, T.T. Introducing an implementation of Brook90 in R. In Geophysical Research Abstracts; EGU2019-13707-1; EGU General Assembly: Munich, Germany, 2019; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobevskii, I.; Kronenberg, R.; Bernhofer, C. Global BROOK90 R Package: An Automatic Framework to Simulate the Water Balance at Any Location. Water 2020, 12, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobevskii, I.; Kronenberg, R.; Bernhofer, C. On the runoff validation of ‘Global BROOK90’ automatic modeling framework. Hydrol. Res. 2021, 52, 1083–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobevskii, I.; Luong, T.T.; Kronenberg, R.; Grünwald, T.; Bernhofer, C. Modelling evaporation with local, regional and global BROOK90 frameworks: Importance of parameterization and forcing. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 3177–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1979 to Present. ERA5: Fifth Generation of ECMWF Atmospheric. 2018. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=form (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Buchhorn, M.; Lesiv, M.; Herold, M.; Tsendbazar, N.E.; Bertles, L.; Smets, B. Copernicus Global Land Service: Land Cover 100 m, Epoch “Year”, Globe (Version V2.0.2). Zenodo. 2019. Available online: https://zenodo.org/record/3243509#.XxFzWcfVLIU (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Hengl, T.; Mendes de Jesus, J.; Heuvelink, G.B.; Ruiperez Gonzalez, M.; Kilibarda, M.; Blagotić, A.; Shangguan, W.; Wright, M.N.; Geng, X.; Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; et al. SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models, Part 1: A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Martinez, G.F. Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: Implications for improving hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoben, W.J.; Freer, J.E.; Woods, R.A. Inherent benchmark or not? Comparing Nash–Sutcliffe and Kling–Gupta efficiency scores. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 4323–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvem, A.; El-Sadek, A. Evaluation of Streamflow Simulation By SWAT Model for The Seyhan River Basin. Çukurova J. Agric. Food Sci. 2018, 33, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobevskii, I. Modelling the Water Balance in Small Catchments: Development of a Global Application for a Local Scale. 2022. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa2-824252 (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Ülker, M.C. The Applicability of the Global BROOK90-R Physically-Based Hydrologic Model in Some River Basin in Turkey: Flow Estimation Study. Master’s Thesis, Konya Technical University, Konya, Türkiye, 2022. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

| Sub Basins | Station Number | Station Name | Elevation (m) | Latitude | Longitude | Time Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Çarşamba Basin | D16A115 | Çarşamba River | 1150 | 37°10′ N | 32°09′ E | 01.1977–07.2016 |

| Körkün Basin | E18A020 | Körkün River–Hacılı Bridge | 167 | 37°17′ N | 35°09′ E | 02.1992–09.2017 |

| Karasu Basin | D21A168 | Karagöbek–Büyük River | 2000 | 40°09′ N | 41°26′ E | 01.1979–09.2020 |

| Data | Type | Dataset | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital elevation model (DEM) | Physical | Amazon Web Services | 3 m–2.5 km |

| Land cover/use map | Physical | Land Cover 100 m | 100 × 100 m |

| Soil texture, stone fracture, depth to bedrock | Physical | SoilGrids250 | 250 × 250 m |

| Precipitation, temperature, wind speed, solar radiation | Meteorological | ERA5 | 0.25° × 0.25° hourly |

| Performance Rating | RSR | NSE | PBIAS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very good | 0.00 ≤ RSR ≤ 0.50 | 0.75 < NSE ≤ 1.00 | PBIAS < ±10 |

| Good | 0.50 < RSR ≤ 0.60 | 0.65 < NSE ≤ 0.75 | ±10 ≤ PBIAS < 15 |

| Satisfactory | 0.60 < RSR ≤ 0.70 | 0.50 < NSE ≤ 0.65 | ±15 ≤ PBIAS < 25 |

| Unsatisfactory | RSR > 0.70 | NSE ≤ 0.50 | PBIAS ≥ ±25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ulker, M.C.; Buyukyildiz, M. Evaluation of Runoff Simulation Using the Global BROOK90-R Model for Three Sub-Basins in Türkiye. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065103

Ulker MC, Buyukyildiz M. Evaluation of Runoff Simulation Using the Global BROOK90-R Model for Three Sub-Basins in Türkiye. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065103

Chicago/Turabian StyleUlker, Muhammet Cafer, and Meral Buyukyildiz. 2023. "Evaluation of Runoff Simulation Using the Global BROOK90-R Model for Three Sub-Basins in Türkiye" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065103

APA StyleUlker, M. C., & Buyukyildiz, M. (2023). Evaluation of Runoff Simulation Using the Global BROOK90-R Model for Three Sub-Basins in Türkiye. Sustainability, 15(6), 5103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065103