Managing Butterfly Career Attitudes: The Moderating Interplay of Organisational Career Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Social Exchange Theory

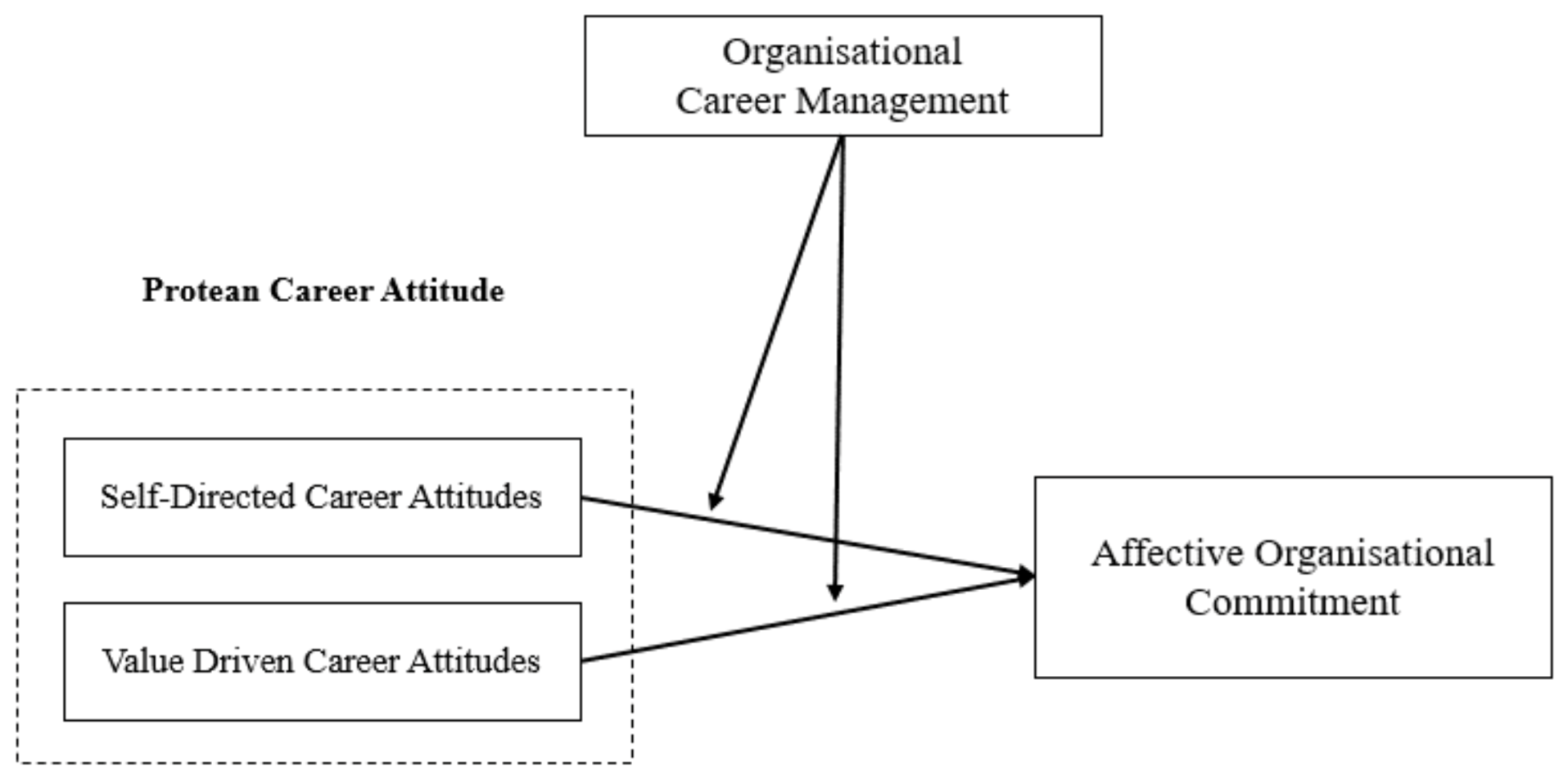

2.2. Protean Career Attitude (P.C.A.) and Affective Organisational Commitment (A.O.C.)

“The contemporary or protean career is the concept where the individuals manage their own career instead of being organised through organisational rewards. The focus of the protean career attitude is training, career development, and work in several organisations, etc. Protean individuals adopt their own career choices, and self-career management is a prominent factor in their lives”.

2.3. Moderating Effect of Organisational Career Management (O.C.M.)

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

3.2. Measures

3.3. Sampling and Data Collection

3.4. Response Rate

4. Statistical Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation

Assessment of Significance of the Structural Model

4.3. Hypotheses of the Direct Effects

4.4. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

4.5. Predictive Relevance (Q2)

4.6. Testing Moderating Effect

5. Discussion, Implications and Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Future Recommendations

5.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasheed, M.I.; Okumus, F.; Weng, Q.; Hameed, Z.; Nawaz, M.S. Career Adaptability and Employee Turnover Intentions: The Role of Perceived Career Opportunities and Orientation to Happiness in the Hospitality Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogmus, C. Millennial Knowledge Workers: The Roles of Protean Career Attitudes and Psychological Empowerment on the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Subjective Career Success. CDI 2019, 24, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, J.P.; Hall, D.T. The Interplay of Boundaryless and Protean Careers: Combinations and Implications. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R.; Malik, O.F. Is Protean Career Attitude Beneficial for Both Employees and Organizations? Investigating the Mediating Effects of Knowing Career Competencies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.C.; Mohd Rasdi, R.; Abu Samah, B.; Abdul Wahat, N.W. Promoting Protean Career through Employability Culture and Mentoring: Career Strategies as Moderator. Euro. J. Train. Dev. 2017, 41, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, P.K.; Cham, T.-H.; Low, M.P.; Lau, T.-C. The Role of Perceived Employability in the Relationship between Protean Career Attitude and Career Success. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2022, 31, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Said, A.-M.; Mohd Rasdi, R.; Abu Samah, B.; Silong, A.D.; Sulaiman, S. A Career Success Model for Academics at Malaysian Research Universities. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2015, 39, 815–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chay, Y.-W.; Aryee, S. Potential Moderating Influence of Career Growth Opportunities on Careerist Orientation and Work Attitudes: Evidence of the Protean Career Era in Singapore. J. Organiz. Behav. 1999, 20, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.U.; Isha, A.S.N.; Sabir, A.A.; Ghazali, Z.; Nübling, M. Does Psychosocial Work Environment Factors Predict Stress and Mean Arterial Pressure in the Malaysian Industry Workers? BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.U.; Bano, S.; Mirza, M.Z.; Isha, A.S.N.; Nadeem, S.; Jawaid, A.; Ghazali, Z.; Nübling, M.; Imtiaz, N.; Kaur, P. Connotations of Psychological and Physiological Health in the Psychosocial Work Environment: An Industrial Context. Work 2019, 64, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Rashid, B. A Conceptual Model of Corporate Social Responsibility Dimensions, Brand Image, and Customer Satisfaction in Malaysian Hotel Industry. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, M.; Shamim, A.; Saleem, S. Re-Interpreting ‘Luxury Hospitality’ through Experienscape, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Well-Being; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 485, ISBN 978-3-031-08092-0. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, M.I.; Shamim, A.; Ahn, J. Implementing ‘Cleanliness Is Half of Faith’ in Re-Designing Tourists, Experiences and Salvaging the Hotel Industry in Malaysia during COVID-19 Pandemic. JIMA 2021, 12, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAH. MAH—Cry of Despair from the Hotel Industry “Hotel Industry in Serious Need of Immediate Rescue”. 2021. Available online: https://hotels.org.my/press/34167-cry-of-despair-from-the-hotel-industry-hotel-industry-in-serious-need-of-immediate-rescue (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Poo, C. The State of the Nation: Hospitality Industry Struggling to Cope Despite Borders Reopening, Brighter Prospects | The Edge Markets. The Edge Malaysia. 2022. Available online: https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/state-nation-hospitality-industry-struggling-cope-despite-borders-reopening-brighter (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Abo-Murad, M.; AL-Khrabsheh, A. Turnover culture and crisis management: Insights from malaysian hotel industry. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y.; Wordsworth, R.; Mills, C.; Wright, S. Career and Work Attitudes of Blue-Collar Workers, and the Impact of a Natural Disaster Chance Event on the Relationships between Intention to Quit and Actual Quit Behaviour. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Guest, D.; Oliveira, T.; Alfes, K. Who Benefits from Independent Careers? Employees, Organizations, or Both? J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleska, K.J.; de Menezes, L.M. Human Resources Development Practices and Their Association with Employee Attitudes: Between Traditional and New Careers. Hum. Relat. 2007, 60, 987–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ngo, H.; Cheung, F. Linking Protean Career Orientation and Career Decidedness: The Mediating Role of Career Decision Self-Efficacy. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, R.; Sparrow, P.; Hernández-Lechuga, G. The Effect of Protean Careers on Talent Retention: Examining the Relationship between Protean Career Orientation, Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit for Talented Workers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 32, 2046–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xiangpei, H. The Researches on Positive Psychological Capital and Coping Style of Female University Graduates in the Course of Seeking Jobs. In Proceedings of 2011 International Symposium—The Female Survival and Development; St Plum-Blossom Press Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011; pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.L.; Marshall, J. Occupational Sources of Stress: A Review of the Literature Relating to Coronary Heart Disease and Mental Ill Health. J. Occup. Psychol. 1976, 49, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Srinivas, E.S.; Lal, J.B.; Topolnytsky, L. Employee Commitment and Support for an Organizational Change: Test of the Three-Component Model in Two Cultures. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, L.J.; Parfyonova, N.M. Employee Commitment in Context: The Nature and Implication of Commitment Profiles. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, J.J.; Brockner, J.; Konovsky, M.A.; Price, K.H.; Henley, A.B.; Taneja, A.; Vinekar, V. Commitment, Procedural Fairness, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Multifoci Analysis. J. Organiz. Behav. 2009, 30, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Eisenberger, R.; Baik, K. Perceived Organizational Support and Affective Organizational Commitment: Moderating Influence of Perceived Organizational Competence: Perceived Organizational Competence. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 558–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. SAGE Books—Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; Advanced Topics in Organizational Behavior, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-7619-0105-1. [Google Scholar]

- Supeli, A.; Creed, P.A. The Longitudinal Relationship Between Protean Career Orientation and Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Intention-to-Quit. J. Career Dev. 2016, 43, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, J.P.; Finkelstein, L.M. The “New Career” and Organizational Commitment: Do Boundaryless and Protean Attitudes Make a Difference? Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, J.; Guest, D.; Mac Davey, K. Who’s in Charge? Graduates’ Attitudes to and Experiences of Career Management and Their Relationship with Organizational Commitment. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2000, 9, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimland, S.; Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Baruch, Y. Career Attitudes and Success of Managers: The Impact of Chance Event, Protean, and Traditional Careers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1074–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direnzo, M.S.; Greenhaus, J.H.; Weer, C.H. Relationship between Protean Career Orientation and Work-Life Balance: A Resource Perspective: PCO and work-life balance. J. Organiz. Behav. 2015, 36, 538–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishanthi, H.M.; Kailasapathy, P. Employee Commitment: The Role of Organizational Socialization and Protean Career Orientation. South Asian J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.; Arshad, M.; Sabir, A.A. How Leaders’ Motivational Language Boost Innovative Work Behavior of Employee in Chinese Service Sectors: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment. Acad. J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtschlag, C.; Masuda, A.D.; Reiche, B.S.; Morales, C. Why Do Millennials Stay in Their Jobs? The Roles of Protean Career Orientation, Goal Progress and Organizational Career Management. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 118, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Dewettinck, K.; Buyens, D. The Professional Career on the Right Track: A Study on the Interaction between Career Self-Management and Organizational Career Management in Explaining Employee Outcomes. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2009, 18, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.L.; Salleh, R.; Hemdi, M.A.B. Effect of Protean Career Attitudes on Organizational Commitment of Employees with Moderating Role of Organizational Career Management. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2016, 6, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Weer, C.H.; Greenhaus, J.H. Managers’ Assessments of Employees’ Organizational Career Growth Opportunities: The Role of Extra-Role Performance, Work Engagement, and Perceived Organizational Commitment. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Çakmak-Otluoğlu, K.Ö. Protean and Boundaryless Career Attitudes and Organizational Commitment: The Effects of Perceived Supervisor Support. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Rothwell, W.J. The Effects of Organizational Learning Climate, Career-Enhancing Strategy, and Work Orientation on the Protean Career. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2009, 12, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. xiii–617. ISBN 978-0-13-815614-5. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, G.N.; White, F.A.; Charles, M.A. Linking Values and Organizational Commitment: A Correlational and Experimental Investigation in Two Organizations. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-292-20878-7. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, M.S.; Isha, A.S.N.B.; Benson, C.; Awan, M.I.; Naji, G.M.A.; Yusop, Y.B. Analyzing the Impact of Psychological Capital and Work Pressure on Employee Job Engagement and Safety Behavior. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1086843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 7th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Djamba, Y.K.; Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Teach. Sociol. 2002, 30, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Pearson Education, Limited: Harlow, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-205-89647-9. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Test of a Three-Component Conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarjan, N.; Arendt, S.W.; Shelley, M. Incongruent Quality Management Perceptions between Malaysian Hotel Managers and Employees. TQM J. 2013, 25, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.S.; Isha, A.S.N.; Mohd Yusop, Y.; Awan, M.I.; Naji, G.M.A. Agility and Safety Performance among Nurses: The Mediating Role of Mindful Organizing. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.S.; Isha, A.S.N.; Yusop, Y.M.; Awan, M.I.; Naji, G.M.A. The Role of Psychological Capital and Work Engagement in Enhancing Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 810145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.S.; Isha, A.S.N.; Awan, M.I.; Yusop, Y.B.; Naji, G.M.A. Fostering Academic Engagement in Post-Graduate Students: Assessing the Role of Positive Emotions, Positive Psychology, and Stress. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 920395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural-Equation-Modeling-with-AMOS Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Geisser, S. A Predictive Approach to the Random Effect Model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-299-95783-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-203-77158-7. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Advanced Methods of Marketing Research; Blackwell Business: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-1-55786-549-6. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, D.; Harris, C. Talent Management and Unions: The Impact of the New Zealand Hotel Workers Union on Talent Management in Hotels (1950–1995). IJCHM 2019, 31, 3838–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, M.L.; Nota, L.; Soresi, S.; Shogren, K.A.; Morningstar, M.E.; Ferrari, L.; Sgaramella, T.M.; DiMaggio, I. A Crisis in Career Development: Life Designing and Implications for Transition. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2019, 42, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Straub, C. Flexible Employment Relationships and Careers in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briscoe, J.P.; Henagan, S.C.; Burton, J.P.; Murphy, W.M. Coping with an Insecure Employment Environment: The Differing Roles of Protean and Boundaryless Career Orientations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Wilton, N. Developing Career Management Competencies among Undergraduates and the Role of Work-Integrated Learning. Teach. High. Educ. 2016, 21, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, A.M.; Adnan, A.H.M.; Mohtar, N.M. Industry 4.0 Skillsets and ‘Career Readiness’: Can Malaysian University Students Face the Future of Work? In Proceedings of the International Invention, Innovative & Creative (InIIC) Conference, Series; MNNF Network: Senawang, Malaysia, 2019; Volume 11, pp. 28–37. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs | Items | SFL | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Directed Career Attitudes | SDCA1 | 0.795 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.74 |

| SDCA2 | 0.911 | ||||

| SDCA3 | 0.916 | ||||

| SDCA4 | 0.742 | ||||

| SDCA5 | 0.875 | ||||

| SDCA6 | 0.872 | ||||

| SDCA7 | 0.869 | ||||

| SDCA8 | 0.929 | ||||

| Value-Driven Career Attitudes | VDCA1 | 0.878 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.55 |

| VDCA2 | 0.895 | 0.916 | 0.930 | 0.572 | |

| VDCA3 | 0.768 | ||||

| VDCA4 | 0.808 | ||||

| VDCA4 | 0.737 | ||||

| VDCA5 | 0.701 | ||||

| VDCA6 | 0.707 | ||||

| (Org) Career Management | OCM1 | 0.752 | |||

| OCM2 | 0.707 | ||||

| OCM3 | 0.805 | ||||

| OCM4 | 0.781 | ||||

| OCM5 | 0.815 | ||||

| OCM6 | 0.820 | ||||

| OCM7 | 0.872 | ||||

| OCM8 | 0.856 | ||||

| OCM9 | 0.869 | ||||

| OCM10 | 0.875 | ||||

| OCM11 | 0.845 | ||||

| OCM12 | 0.755 | ||||

| OCM13 | 0.811 | ||||

| Affective Organisational Commitment | AOC1 | 0.807 | 0.886 | 0.917 | 0.688 |

| AOC2 | 0.861 | ||||

| AOC3 | 0.855 | ||||

| AOC4 | 0.823 | ||||

| AOC5 | 0.811 | ||||

| AOC6 | 0.876 | ||||

| AOC7 | 0.799 | ||||

| AOC8 | 0.832 |

| Constructs | SDCA | VDCA | OCM | AOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDCA | 0.865 | |||

| VDCA | 0.665 | 0.832 | ||

| OCM | 0.797 | 0.548 | 0.898 | |

| Affective (Org) Commitment | 0.621 | 0.517 | 0.618 | 0.829 |

| Constructs | SDCA | VDCA | OCM | AOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDCA | ||||

| VDCA | 0.807 | |||

| OCM | 0.799 | 0.653 | ||

| Affective (Org) Commitment | 0.702 | 0.617 | 0.699 |

| Constructs | Tolerance | V.I.F. |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Directed Career Attitudes | ||

| Value-Driven Career Attitudes | 0.807 | |

| Organisational Career Management | 0.799 | 0.653 |

| Affective Organisational Commitment | 0.702 | 0.617 |

| Hypotheses | Std Beta | T Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | −0.183 | 0.089 | 2.423 | 0.000 ** |

| H1b | −0.325 | 0.075 | 4.335 | 0.000 ** |

| Constructs | SDCA |

|---|---|

| Self-Directed Career Attitudes | 0.323 |

| Value-Driven Career Attitudes | 0.473 |

| Hypotheses | Std Beta | T Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2a | 0.155 | 2.214 | 0.000 * | Supported |

| H2b | 0.255 | 3.785 | 0.000 * | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.L.; Salleh, R.; Javaid, M.U.; Arshad, M.Z.; Saleem, M.S.; Younas, S. Managing Butterfly Career Attitudes: The Moderating Interplay of Organisational Career Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065099

Khan ML, Salleh R, Javaid MU, Arshad MZ, Saleem MS, Younas S. Managing Butterfly Career Attitudes: The Moderating Interplay of Organisational Career Management. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065099

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Muhammad Latif, Rohani Salleh, Muhammad Umair Javaid, Muhammad Zulqarnain Arshad, Muhammad Shoaib Saleem, and Samia Younas. 2023. "Managing Butterfly Career Attitudes: The Moderating Interplay of Organisational Career Management" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065099

APA StyleKhan, M. L., Salleh, R., Javaid, M. U., Arshad, M. Z., Saleem, M. S., & Younas, S. (2023). Managing Butterfly Career Attitudes: The Moderating Interplay of Organisational Career Management. Sustainability, 15(6), 5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065099