Attitudinal and Behavioral Loyalty: Do Psychological and Political Factors Matter in Tourism Development?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Attitudinal and Behavioral Loyalty

2.2. Political Risk and Tourism

3. Conceptual Framework and Research Hypothesis

4. Methods and Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Demographic Variables: Local and International Tourists

5.2. Psychological Variables: Local and International Tourist Comparison

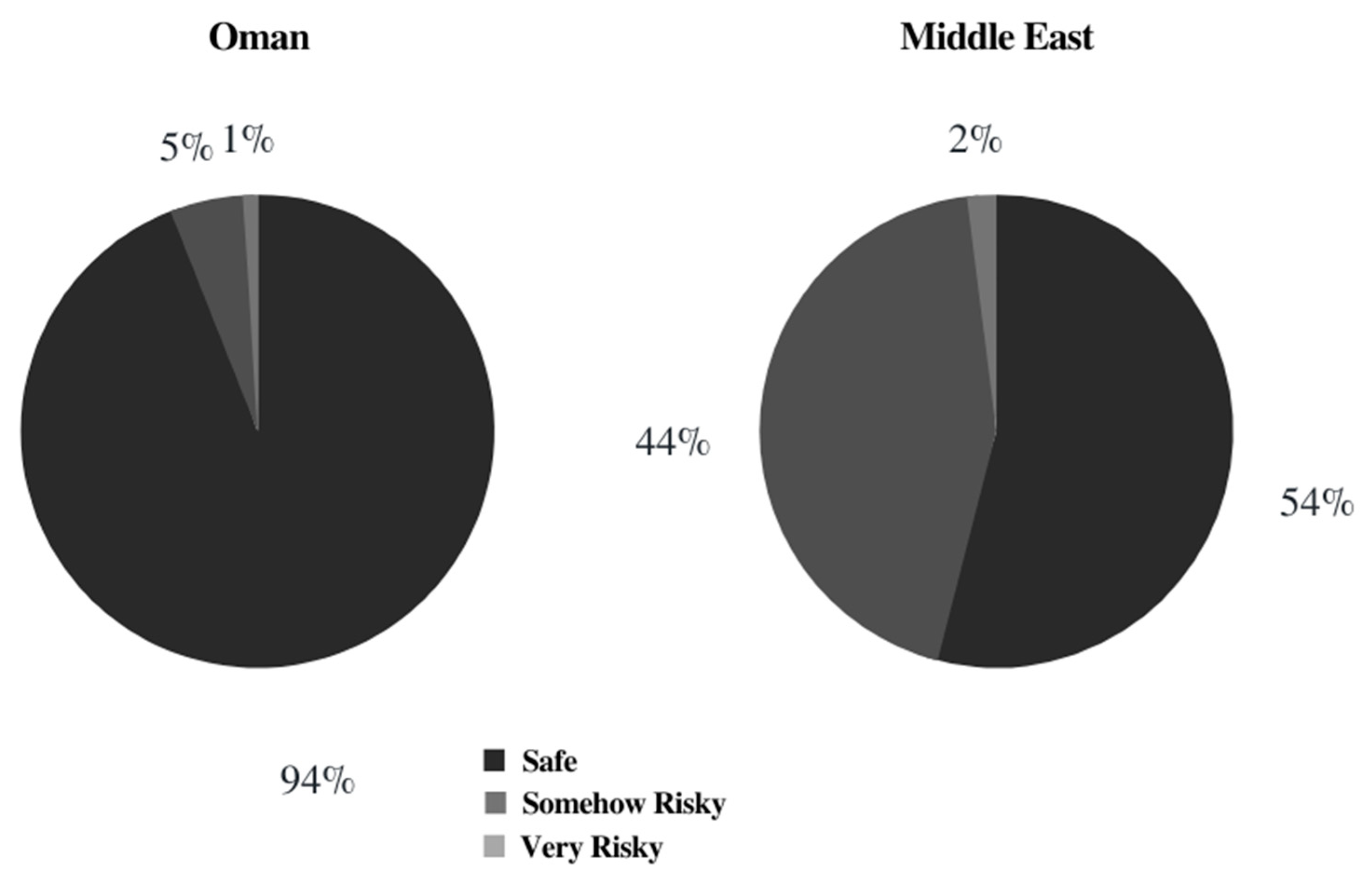

5.3. Political Risk Perception of the Middle East and Oman

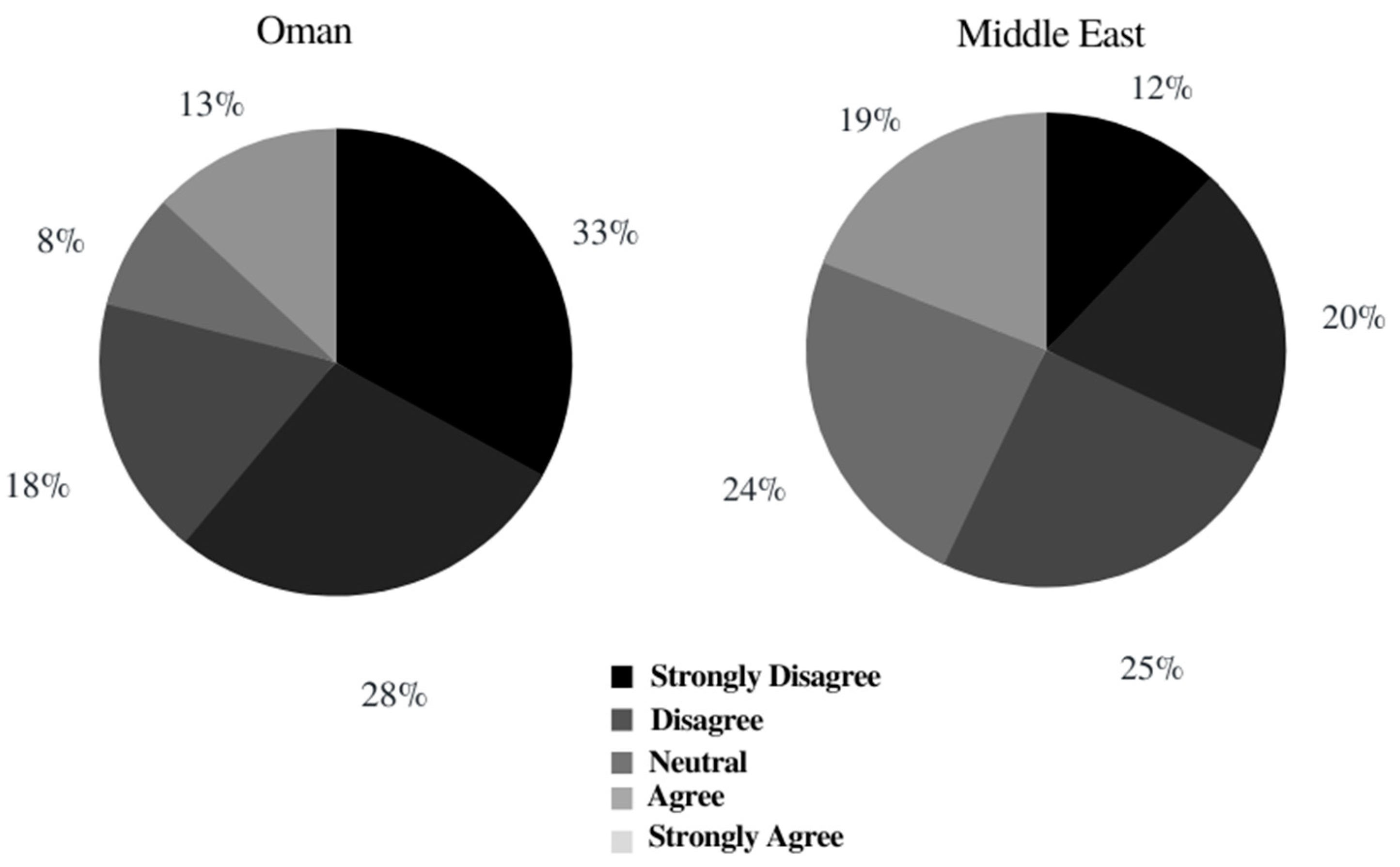

5.4. Oman’s Political Neutrality

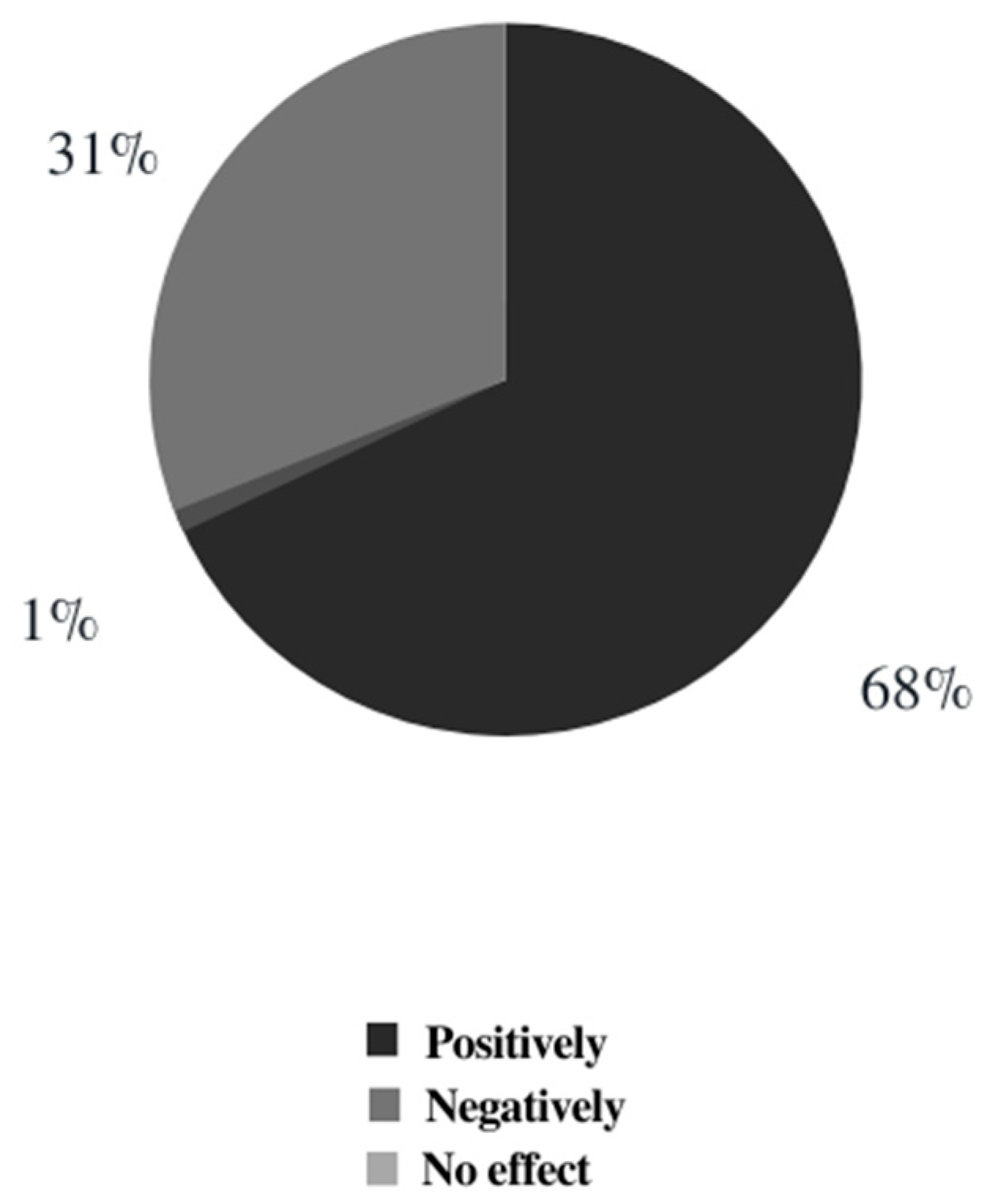

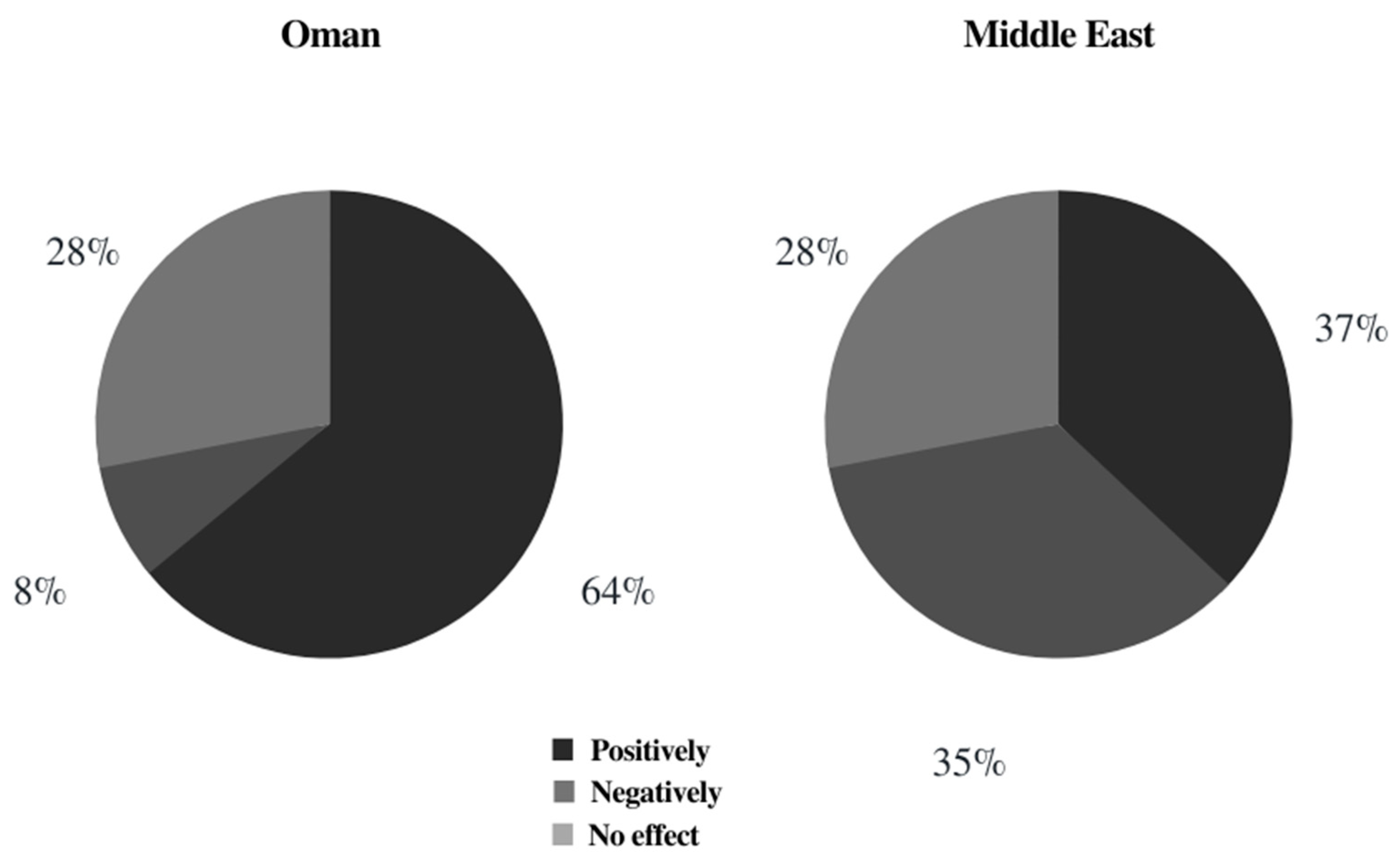

5.5. Media Coverage

5.6. Analysis of Attitudinal and Behavioral Loyalty: Psychological and Risk Variables

5.6.1. Attitudinal Loyalty

5.6.2. Behavioral Loyalty

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Tourism Organization. Tourism in the MENA Region. 2019. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284420896 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- The World Tourism Organization. Tourism Highlights, 2010 ed.; WTO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The World Travel and Tourism Council–WTTC. Yearbook of Tourism Statistics; WTTC Database: Country Analysis. 2019. Available online: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Groizard, J.L.; Ismael, M.; Santana-Gallego, M. Political upheavals, tourism flight, and spillovers: The case of the Arab spring. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertaş, M.; Sel, Z.G.; Kırlar-Can, B.; Tütüncü, Ö. Effects of crisis on crisis management practices: A case from Turkish tourism enterprises. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1490–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakabati, Y. Tourism in the Middle East: Conflicts, crises and economic diversification, some critical issues. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E. Destination marketing and image repair during tourism crises: The case of Egypt. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 28, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abri, I.; Önel, G.; Grogan, K.A. Oil revenue shocks and the growth of the non-oil sector in an oil-dependent economy: The case of Oman. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2019, 9, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Abri, I.; Al Bulushi, A. The Role of Institutional Quality in Economic Efficiency in the GCC Countries. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2022, 12, 1591–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaibet, L.; Al Siyabi, M.; Boughanmi, H.; Al Abri, I.; Al Akhzami, S. Doing Business in the COMESA Region: The Role of Innovation and Trade Facilitation. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 2022, 21, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughanmi, H.; Al-Saadi, F.; Zaibet, L.; Al Abri, I.; Akintola, A. Trade in intermediates and agro-food value chain integration: The case of the Arab region. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211002513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafiero, G.; Yefet, A. Oman and the GCC: A solid relationship? Middle East Policy 2016, 23, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor, I. Tourism Flows Inbound Oman. Country Sector Briefing. 2011. Available online: http://www.euromonitor.com/travel-and-tourism-in-oman/report (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Issa, I.A.; Altinay, L. Impacts of political instability on tourism planning and development: The case of Lebanon. Tour. Econ. 2006, 12, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Statistical and Information, (NCSI). Tourism Statistics, 5th ed.; NCSI: Muscat, Oman, 2019; pp. 2–3. Available online: https://www.ncsi.gov.om/Elibrary/Pages/LibraryContentView.aspx (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Sharifpour, M.; Walters, G.; Ritchie, B.W. Risk perception, prior knowledge, and willingness to travel: Investigating the Australian tourist market’s risk perceptions towards the Middle East. J. Vacat. Mark. 2014, 20, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAS. Saudi Tourism Outlook, June 2011. The Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities. 2011. Available online: http://www.mas.gov.sa/ (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Nicolau, J.L.; Mas, F.J. Heckit modeling of tourist expenditure: Evidence from Spain. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2005, 16, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergoupis, T.; Steuer, M. Holiday taking and income. Appl. Econ. 2003, 35, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melenberg, B.; Soest, A.V. Parametric and semi-parametric modeling of vacation expenditures. J. Appl. Econom. 1996, 11, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Mateo, S.; Pou, L. An analysis of households’ appraisal of their budget constraints for potential participation in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellstrom, J. A bivariate count data model for household tourism demand. J. Appl. Econom. 2006, 21, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L.; Mas, F.J. Stochastic modeling: A three-stage tourist choice process. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemerding, M.; Oppewal, H.; Timmermans, H. A constraints-induced model of park choice. Leis. Sci. 1999, 21, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P. Fundamentals of Tourist Motivation. In Tourism Research: Critiques and Challenges; Pearce, D.G., Butler, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P. Tourist Behaviour: Themes and Conceptual Schemes; Channel View Publication: Clevedon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G.M. Anomie. Ego-enhancement and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1977, 4, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.R.J.; Zahari, M.S.M.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Rahman, A.R.A. Foreign tourist satisfaction, commitment and revisit intention: Exploring the effect of environmental turbulence in the Arab region. J. Islam. Mark. 2022, 12, 2480–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Tasci, A.D. The influence of post-visit emotions on destination loyalty. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechinda, P.; Serirat, S.; Gulid, N. An examination of tourists’ attitudinal and behavioral loyalty: Comparison between domestic and international tourists. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santana, A.; Moreno-Gil, S. New trends in information search and their influence on destination loyalty: Digital destinations and relationship marketing. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Cai, L.A. Destination loyalty and communication—a relationship-based tourist behavioral model. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2012, 6, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Darzi, M.A. Antecedents of tourist loyalty to tourist destinations: A mediated-moderation study. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 4, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Adhikari, D.; Fahmy, S.; Kang, S. Exploring the impacts of national image, service quality, and perceived value on international tourist behaviors: A Nepali case. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.; Callarisa, L.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Moliner, M.A. Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy, S.; Ratchford, B.T.; Talukdar, D. Consumer Information Search Re- visited: Theory and Empirical Analysis. Consum. Res. 1997, 23, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Tussyadiah, I.P. Exploring familiarity and destination choice in international tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, B.; Morrison, A.M.; Tseng, C.; Chen, Y.C. How country image affects tourists’ destination evaluations: A moderated mediation approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 904–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, S.F. Tourism, terrorism, and political instability. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 416–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Yap, G. The Moderation Effects of Political Instability and Terrorism on Tourism Development: A Cross-Country Panel Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 510–513. Available online: http://jtr.sagepub.com (accessed on 6 May 2019). [CrossRef]

- Teye, V.B. Coups D’etat and African Tourism: A Study of Ghana. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; Morakabati, Y. Tourism activity, terrorism and political instability within the Commonwealth: The cases of Fiji and Kenya. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism and Politics: Policy, Power and Place; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, L.K.; Waugh Jr, W.L. Terrorism and tourism as logical companions. Tour. Manag. 1986, 7, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, J. The Practice of English Language Teaching; Longman Press: Essex, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Drakos, K.; Kutan, A.M. Regional effects of terrorism on tourism in three Mediterranean countries. J. Confl. Resolut. 2003, 47, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wong, K.K. A spatial econometric approach to model spillover effects in tourism flows. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanta, W.; Alkazemi, M.F. Agenda-setting: History and research tradition. Int. Encycl. Media Eff. 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, K.A. Framing Islam: An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of Terrorism Since 9/11. Commun. Stud. 2011, 62, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurlin, T.; Jaković, B.; Miloloža, I. Twitter usage in Tourism: Literature Review. Bus. Syst. Res. J. Int. J. Soc. Adv. Bus. Inf. Technol. (BIT) 2019, 10, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Duarte, P.; Henriquez, C. Travelers’ use of social media: A clustering approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.C. Perceived risk and destination knowledge in the satisfaction-loyalty intention relationship: An empirical study of European tourists in Vietnam. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 33, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramoniam, S.; Al-Essai, S.; Al-Marashadi, A.; Al-Kindi, A. SWOT analysis on Oman tourism: A case study. J. Econ. Dev. Manag. IT Financ. Mark. 2010, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

| Variables Definition | Measurement Item and Its Reliability |

|---|---|

| Behavioral loyalty | 1 item measured by the number of repeated visits. |

| Attitudinal loyalty | 5 items, 5-point rating scale *, α = 0.88 (1) I consider myself a loyal visitor of tourist attraction places in Oman (2) My next journey will most likely be visiting tourist attraction places in Oman (3) I would visit tourist attraction places in Oman for several times (4) I will recommend local tourism to people who seek my advice (5) I would tell other positive things about tourist attraction places I visited in Oman |

| Satisfaction | 3 items, 5-point rating scale, α = 0.85 (1) How does tourist attraction places in Oman, in general, rate compared to what you expected? (2) Was this visit worth your time and effort? (3) Overall, how satisfied were you with your holiday in Oman? |

| Perceived value | 3 items, 5-point rating scale, α = 0.88 (1) Spending my vacation in tourist attraction places in Oman represents good value. (2) Considering what I pay to spend my vacation in tourist attraction places in Oman, I get much more than my money’s worth. (3) I consider traveling to these places to be a bargain because of the benefits I receive. |

| Attachment | 3 items, 5-point rating scale, α = 0.87 (1) Tourist attraction places in Oman mean a lot to me. (2) I enjoy staying in Oman more than any other place. (3) I am very attached to Oman |

| Familiarity | 3 items, 5-point rating scale, α = 0.89 (1) How familiar are you with Oman as a vacation destination? (2) How interested are you Oman as a vacation destination? (3) How knowledgeable are you about vacation travel to this place relative to other people from your country? |

| Push motivation | 5 items, 5-point rating scale, α = 0.80 (1) I travel to experience a simpler lifestyle. (2) I travel to experience new and different lifestyles (3) I travel to meet new and different people (4) I travel to do/seek things that represent a destination’s unique identity (5) I travel to visit friends and relatives |

| Pull motivation | 8 items, 5-point rating scale, α = 0.87 (1) I travel to experience the destination’s history, archeology, and places (2) I choose my destination depending on the availability of visits to natural ecological sites (3) I travel to experience the interesting rural countryside (4) I travel for opportunities to increase knowledge (5) I travel to experience arts and cultural attractions (6) Personal safety is an important factor when determining travel destinations (7) Availability of pre-trip and in-country tourist information is an important factor when determining travel destinations (8) Availability of activities for the entire family is an important factor when determining travel destinations |

| Political risk perception | 3 items, 5-point rating scale, α = 0.66 (1) Being a victim of a terrorist act is a concern when visiting the Middle East (2) Being a victim of a terrorist act is a concern when visiting Oman (3) I think spreading the word internationally regarding Oman neutrality in international relations and the very low crime rate will attract more tourists to the country 5 items, 3-point rating scale **, α = 0.60 (1) How risky would you perceive the Middle East region? (2) How risky would you perceive Oman? (3) I think the media coverage of the region has affected the tourism sector in the region (4) I think the media coverage of Oman has affected the tourism sector in Oman (5) Oman neutrality in international relations affect (could affect) my visit to the country 4 items, Yes/No questions (1) Do you believe that perceived risk in the Middle East region reflects reality? (2) Did the instability situation in the neighborhood countries (Iran, Yamen, Iraq…etc.) influenced your visit to Oman? (3) Do you have any background information about the crime rate in Oman? (4) Does Oman neutrality in international relations affect your visit or could affect your future visit to the country? |

| Category | Local | International |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Gender Female Male | 60 (30%) 145 (71%) | 74 (45%) 91 (55%) |

| Age Less than 30 30–49 50 and higher | 70 (34%) 107 (52%) 28 (14%) | 6 (4%) 90 (54%) 69 (42%) |

| Children No Yes | 41 (20%) 164 (80%) | 60 (36%) 105 (64%) |

| Marital status Single Separated Married Widowed Divorced | 45 (22%) 0 (0%) 155 (76%) 5 (2%) 0 (0%) | 18 (11%) 2 (1%) 142 (86%) 1 (1%) 2 (1%) |

| Education Bachelor’s degree or higher Less than bachelor’s degree | 50 (24%) 155 (76%) | 159 (97%) 5 (3%) |

| Occupation Professional Administrative, managerial, and entrepreneur commercial Production and agriculture worker Government officer state enterprise Housewife, student, retired, unemployed, and others | 94 (46%) 8 (4%) 12 (6%) 2 (1%) 89 (43%) | 142 (86%) 5 (3%) 0 (0%) 8 (5%) 10 (6%) |

| Income Less than $50,000 $50,000 and higher Not specified | 74 (36%) 101 (49%) 30 (15%) | 107 (64%) 58 (35%) 0 (0%) |

| Residence | Muscat 20 (10%) Dhofar 13 (6%) Musandam 2 (1%) AlBuraimi 7 (3%) AlWusta 5 (1%) ADhaklyia 43 (21%) ADhahira 17 (8%) AlBatinah 70 (34%) AlSharqiyah 32 (16%) | Africa 6 (4%) Asia 72 (44%) Europe 15 (9%) GCC 40 (24%) The Americas 2 (1%) Other Arab Countries 18 (11%) Other 12 (7%) |

| Local Mean | International Mean | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Push Motivations | |||

| Seeking simple lifestyle | 3.48 | 3.87 | 0.00 |

| Seeking new lifestyle | 3.72 | 4.03 | 0.00 |

| Meeting new people | 3.07 | 4.04 | 0.00 |

| Experience the destination’s uniqueness | 3.75 | 4.13 | 0.00 |

| Visiting friends/relatives | 3.68 | 3.40 | 0.00 |

| B. Pull Motivations | |||

| Experience history and archeology | 3.64 | 4.04 | 0.00 |

| Availability of natural ecology sites | 4.28 | 3.85 | 0.00 |

| Experience rural countryside | 3.95 | 3.91 | 0.61 |

| Learning and gaining knowledge | 3.39 | 4.07 | 0.00 |

| Experience culture and arts | 3.45 | 4.02 | 0.00 |

| Personal safety is key when choosing a destination | 4.66 | 4.39 | 0.00 |

| Availability of tourist information | 4.41 | 4.27 | 0.10 |

| Availability of activities for the whole family | 4.56 | 4.18 | 0.00 |

| C. Destination Experience | |||

| Satisfaction average | 3.57 | 4.17 | 0.00 |

| Perceived Value average | 3.27 | 3.86 | 0.00 |

| Attachment average | 4.09 | 4.13 | 0.65 |

| Familiarity average | 3.27 | 3.99 | 0.00 |

| Disagree and Strongly Disagree | Agree and Strongly Agree | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| International | Local | International | Local | |

| A. Satisfaction | ||||

| Expectation | 8% | 35% | 83% | 29% |

| Worthiness | 7% | 4% | 85% | 76% |

| Satisfaction | 7% | 2% | 82% | 84% |

| B. Perceived Value | ||||

| Monetary gain | 12% | 33% | 69% | 32% |

| Bargain value | 13% | 21% | 68% | 35% |

| Perceived value | 8% | 5% | 80% | 67% |

| C. Attachment | ||||

| Emotional Connection | 9% | 2% | 83% | 87% |

| Enjoyment | 11% | 3% | 68% | 77% |

| Attachment | 7% | 1% | 80% | 95% |

| D. Familiarity | ||||

| Interest | 9% | 14% | 74% | 55% |

| Knowledge | 10% | 35% | 71% | 43% |

| Familiarity | 10% | 20% | 72% | 42% |

| Variables | Coefficient | Std. Error | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction average | 1.79 | 0.43 | 0.00 |

| Perceived value average | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.05 |

| Attachment average | 0.93 | 0.32 | 0.00 |

| Familiarity average | −0.04 | 0.32 | 0.91 |

| Perceived risk of Oman | 2.75 | 1.08 | 0.01 |

| Media coverage of tourism | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.58 |

| Neutrality policy effect | 0.86 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| Variables | Coefficient | Std. Error | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 6.85 | 4.29 | 0.11 |

| Satisfaction Average | 3.30 | 1.72 | 0.06 |

| Perceived Value Average | 0.33 | 1.22 | 0.79 |

| Attachment Average | 4.61 | 1.25 | 0.00 |

| Familiarity Average | −2.67 | 1.15 | 0.02 |

| Future Trips | −0.08 | 0.98 | 0.94 |

| Revisiting | 0.27 | 1.15 | 0.82 |

| Recommendations | −5.26 | 1.53 | 0.00 |

| Positive feedback | −0.83 | 1.50 | 0.58 |

| Perceived risk of Oman | 4.53 | 2.39 | 0.06 |

| Media coverage of tourism | −0.47 | 0.67 | 0.48 |

| Neutrality policy effect | −1.89 | 1.47 | 0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Abri, I.; Alkazemi, M.; Abdeljalil, W.; Al Harthi, H.; Al Maqbali, F. Attitudinal and Behavioral Loyalty: Do Psychological and Political Factors Matter in Tourism Development? Sustainability 2023, 15, 5042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065042

Al Abri I, Alkazemi M, Abdeljalil W, Al Harthi H, Al Maqbali F. Attitudinal and Behavioral Loyalty: Do Psychological and Political Factors Matter in Tourism Development? Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065042

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Abri, Ibtisam, Mariam Alkazemi, Waed Abdeljalil, Hala Al Harthi, and Fatema Al Maqbali. 2023. "Attitudinal and Behavioral Loyalty: Do Psychological and Political Factors Matter in Tourism Development?" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065042

APA StyleAl Abri, I., Alkazemi, M., Abdeljalil, W., Al Harthi, H., & Al Maqbali, F. (2023). Attitudinal and Behavioral Loyalty: Do Psychological and Political Factors Matter in Tourism Development? Sustainability, 15(6), 5042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065042