Does Green Mindfulness Promote Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Intrinsic Motivation through the Lens of Self-Determination Theory

2.2. Green Mindfulness and Green Organizational Behavior

2.3. Green Mindfulness and Green Intrinsic Motivation

2.4. The Mediating Role of Green Intrinsic Motivation

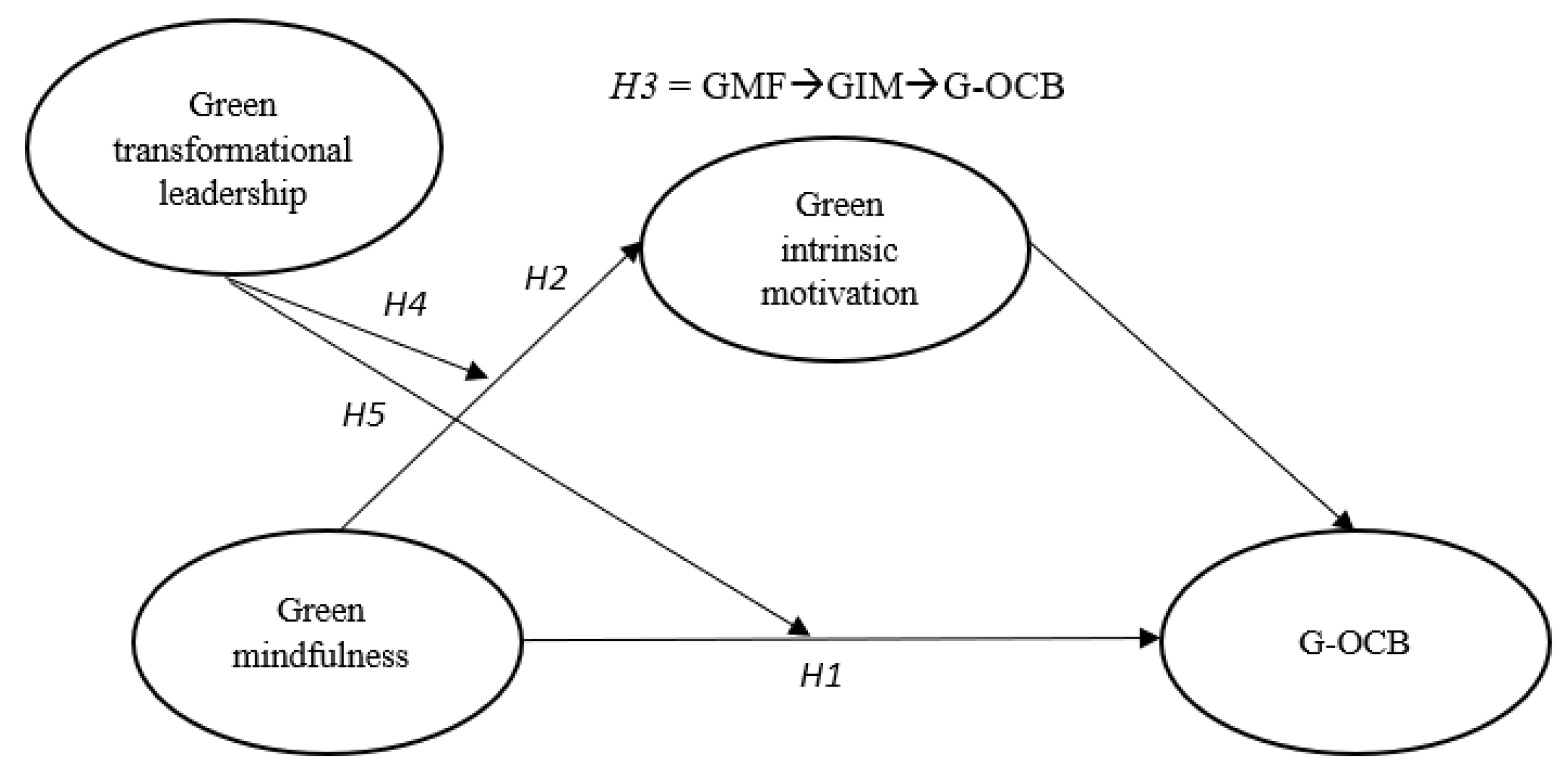

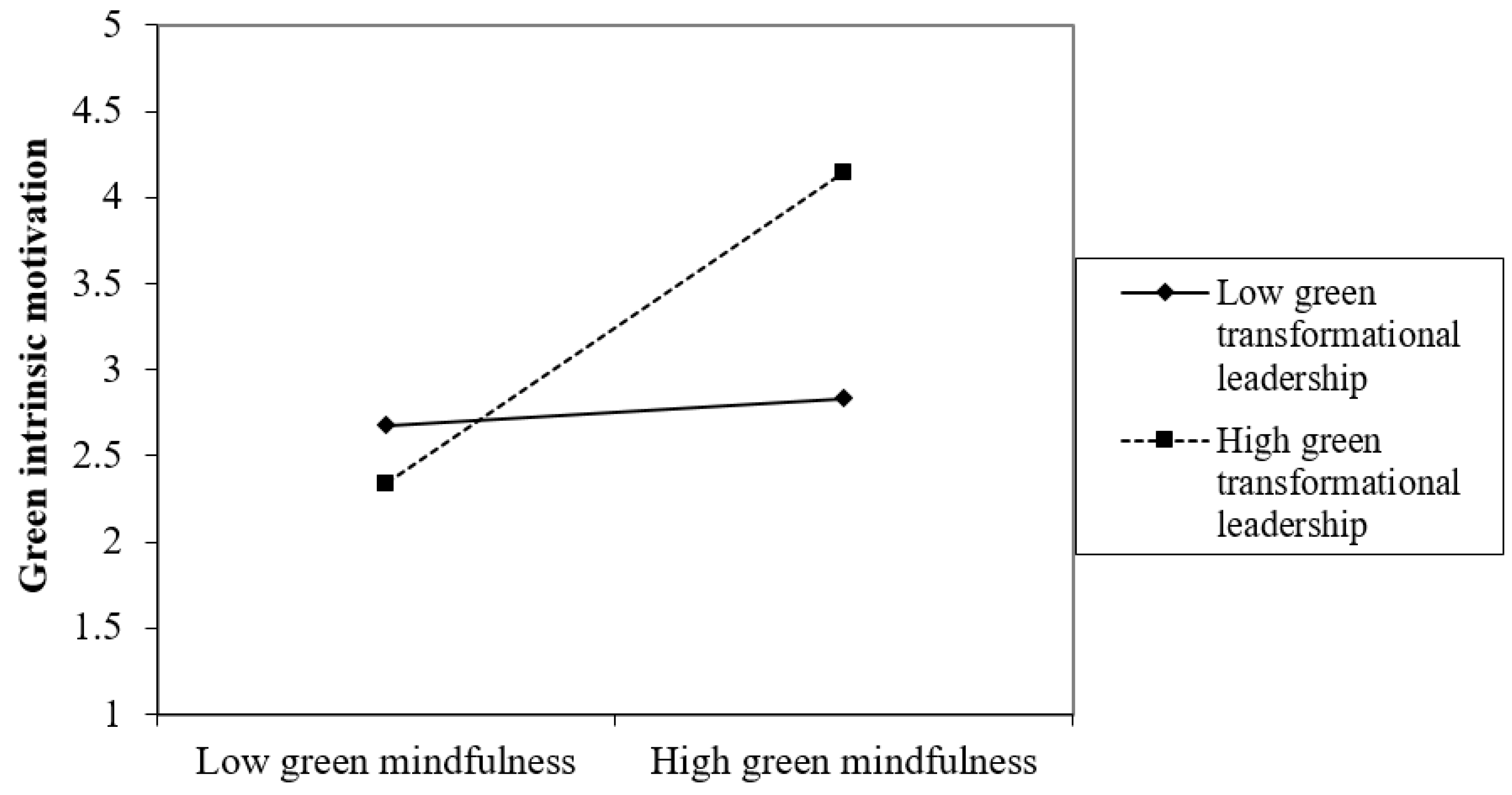

2.5. The Moderating Role of Green Transformational Leadership

2.6. Moderated Mediation Model

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Materials/Instruments

3.3.1. Green Mindfulness

3.3.2. Green Transformational Leadership

3.3.3. Green Intrinsic Motivation

3.4. Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior

3.5. Control Variables

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- i.

- Green mindfulness has a significant positive relationship with G-OCB;

- ii.

- Green intrinsic motivation significantly mediates the association between green mindfulness and G-OCB;

- iii.

- Green transformational leadership underpins the direct association between green mindfulness and green intrinsic motivation, and the indirect relationship between green mindfulness and G-OCB, mediated by green intrinsic motivation.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hole, Y.; Snehal, P. Challenges and solutions to the development of the tourism and hospitality industry in India. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leisur. 2019, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S.I.; Ye, S.; Wang, D.; Law, R. Engaging customers in value co-creation through mobile instant messaging in the tourism and hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, M.F.; Omar, M.K.; Wei, F.; Rasheed, M.I.; Hameed, Z. Green HRM and psychological safety: How transformational leadership drives follower’s job satisfaction. Curr. Issue Tour. 2021, 24, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Ali, F.; Shafique, I. Green mindfulness and green creativity nexus in hospitality industry: Examining the effects of green process engagement and CSR. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2653–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, L.W.; Liu, M.S.; Lin, J.J. Green human resource management and green organizational citizenship behavior: Do green culture and green values matter? Int. J. Man. 2021, 43, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Effect of green transformational leadership on green creativity: A study of tourist hotels. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethic. 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corp. Soc. Res. Env. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Lee, B. Pride, mindfulness, public self-awareness, affective satisfaction, and customer citizenship behaviour among green restaurant customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Chin, T.; Hu, D. The continuous mediating effects of GHRM on employees’ green passion via transformational leadership and green creativity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Otto, S.; Schrader, U. Mindfully green and healthy: An indirect path from mindfulness to ecological behavior. Front. Psy. 2018, 8, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bhutto, T.A.; Xuhui, W.; Maitlo, Q.; Zafar, A.U.; Bhutto, N.A. Unlocking employees’ green creativity: The effects of green transformational leadership, green intrinsic, and extrinsic motivation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Res. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Theories of Self-Determination. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 10, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Conceptualizations of Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination. In Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Amer. Psy. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Comparative Incentive Systems. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 627–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, S.; Polania-Reyes, S. Economic incentives and social preferences: Substitutes or complements? J. Econ. Lit. 2012, 50, 368–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.F. Creativity in performance. Mus. Imagin. Mult. Persp. Create. Perf. Percep. 2012, 9, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, A. Creativity and Performance in Industrial Organization; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lofquist, E.A.; Matthiesen, S.B. Viking leadership: How Norwegian transformational leadership style effects creativity and change through organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Int. J. Cros. Cultur. Manag. 2018, 18, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R.K. The interdisciplinary study of creativity in performance. Create. Res. J. 1998, 11, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, D. Can you train employees to solve problems? Perf. Imp. 2001, 40, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martz, B.; Hughes, J.; Braun, F. Creativity and problem-solving: Closing the skills gap. J. Comp. Info. Sys. 2017, 57, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.W.; Chen, F.F.; Luan, H.D.; Chen, Y.S. Effect of green organizational identity, green shared vision, and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment on green product development performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmesti, M.; Merrilees, B.; Winata, L. “I’m mindfully green”: Examining the determinants of guest pro-environmental behaviors (PEB) in hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, D.A.; Çetin, F. Shedding Some Light on the Blind Spots Concerning Organizational Citizenship Behavior. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Bass, B.M., Riggio, R.E., Eds.; Transformational Leadership; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2006; p. 10510. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.N.Q.; Ngo, L.V.; Surachartkumtonkun, J. When do-good meets empathy and mindfulness. J. Retail. Consum. Ser. 2019, 50, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination. Ref. Modul. Neurosci. Biobehav. 2015, 11, 437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C.; Malycha, C.P.; Schafmann, E. The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 21, 486–491. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M. Componential Theory of Creativity. In Encyclopedia of Management Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psy. 2003, 84, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness interventions. Ann. Rev. Psy. 2017, 68, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M.; Duffy, M.K.; Bono, J.E.; Yang, T. Mindfulness at Work. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, B.; van Woerkom, M.; Menting, C. Mindfulness as substitute for transformational leadership. J. Manag. Psy. 2017, 32, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neace, S.M.; Hicks, A.M.; DeCaro, M.S.; Salmon, P.G. Trait mindfulness and intrinsic exercise motivation uniquely contribute to exercise self-efficacy. J. Am. Colleg. Health 2020, 70, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffault, A.; Bernier, M.; Juge, N.; Fournier, J.F. Mindfulness may moderate the relationship between intrinsic motivation and physical activity: A cross-sectional study. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.S.; Lau, X.S.; Kung, Y.T.; Kailsan, R.A.L. Openness to experience enhances creativity: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation and the creative process engagement. J. Create. Behav. 2019, 53, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, R.A.; Atan, T. The influence of ethical leadership on academic employees’ organizational citizenship behavior and turnover intention: Mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Manag. Dec. 2018, 57, 583–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramitha, A.; Indarti, N. Impact of the environment support on creativity: Assessing the mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Pro.-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 115, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panditharathne, P.N.K.W.; Chen, Z. An integrative review on the research progress of mindfulness and its implications at the workplace. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Pieta, P. The impact of green human resource management on organizational citizenship behaviors: The mediating role of organizational identification and job satisfaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational Leadership; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, L.A. Transformational leadership and follower creativity: The moderating effect of leader humor. Rev. Bus. Res. 2009, 9, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Vogus, T.J.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Organizational mindfulness and mindful organizing: A reconciliation and path forward. Acad. Manag. Lear. Educ. 2012, 11, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.; Ayoko, O.B. Employees’ self-determined motivation, transformational leadership and work engagement. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 27, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone, W.A. Meaning in method: The rhetoric of quantitative and qualitative research. Educ. Res. 1987, 16, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B. Toward a new classification of nonexperimental quantitative research. Educ. Res. 2001, 30, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Fassot, G. Testing Moderating Effects in PLS Models: An Illustration of Available Procedures. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications in Marketing and Related Fields; Vinziv, E., Chinw, W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.J.; Seaman, A.E. Corporate governance and mindfulness: The impact of management accounting systems change. J. App. Bus. Res. 2010, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Hill, K.G.; Hennessey, B.A.; Tighe, E.M. The Work Preference Inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Phan, Q.P.T.; Tučková, Z.; Vo, N.; Nguyen, L.H. Enhancing the organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of green training and organizational culture. Management & Marketing. Chall. Know Soc. 2018, 13, 1174–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Birnbrich, C. The impact of fraud prevention on bank-customer relationships: An empirical investigation in retail banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2012, 30, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, M.A. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and organizational citizenship behavior: A functional approach to organizational citizenship behavior. J. Psy. Iss. Organ. Cultur. 2011, 2, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazauskaite-Zabielske, J.; Urbanaviciute, I.; Bagdziuniene, D. The role of prosocial and intrinsic motivation in employees’ citizenship behaviour. Bal. J. Manag. 2015, 10, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.I.; Iqbal, M.A.; Shahbaz, M. Pakistan tourism industry and challenges: A review. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchenbach, A.; Hanna, P.; Miller, G. Rethinking decent work: The value of dignity in tourism employment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1026–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, T. Person-organization fit and person-job fit in employee selection: A review of the literature. Osak. Keid. Rons. 2004, 54, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. App. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislavská, L.K.; Pilař, L.; Margarisová, K.; Kvasnička, R. Corporate social responsibility and social media: Comparison between developing and developed countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Loadings | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green mindfulness | 0.585 | 0.8810 | 0.843 | |

| GMF1 | 0.723 | |||

| GMF2 | 0.811 | |||

| GMF3 | 0.687 | |||

| GMF4 | 0.800 | |||

| GMF5 | 0.765 | |||

| GMF6 | 0.792 | |||

| Green transformational leadership | 0.535 | 0.890 | 0.856 | |

| GTL1 | 0.667 | |||

| GTL2 | 0.782 | |||

| GTL3 | 0.712 | |||

| GTL4 | 0.784 | |||

| GTL5 | 0.612 | |||

| GTL6 | 0.812 | |||

| Green intrinsic motivation | 0.529 | 0.856 | 0.814 | |

| GIM1 | 0.646 | |||

| GIM2 | 0.764 | |||

| GIM3 | 0.742 | |||

| GIM4 | 0.653 | |||

| GIM5 | 0.731 | |||

| GIM6 | 0.814 | |||

| Green organizational citizenship behavior | 0.523 | 0.800 | 0.771 | |

| G-OCB1 | 0.702 | |||

| G-OCB2 | 0.750 | |||

| G-OCB3 | 0.724 | |||

| G-OCB4 | 0.734 | |||

| G-OCB5 | 0.723 | |||

| G-OCB6 | 0.672 | |||

| G-OCB7 | 0.754 |

| Fornell–Larcker Criterion | HTMT Criterion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM | GTL | GIM | G-OCB | GM | GTL | GIM | G-OCB | |

| GM | 0.764 | |||||||

| GTL | 0.543 | 0.731 | 0.653 CI.0.900 [0.550;0.711] | |||||

| GIM | 0.574 | 0.452 | 0.727 | 0.816 CI.0.900 [0.756;0.882] | 0.660 CI.0.900 [0.612;0.732] | |||

| G-OCB | 0.612 | 0.518 | 0.356 | 0.723 | 0.524 CI.0.900 [0.453;0.582] | 0.713 CI.0.900 [0.630;0.795] | 0.776 CI.0.900 [0.718;0.842] | |

| Hypotheses | β | CI (5%, 95%) | SE | t-Value | p-Value | Decision | f2 | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 1 | 0.023 (n.s.) | (−0.050, 0.044) | 0.022 | 0.532 | 0.615 | ||||

| Gender 2 | 0.079 (n.s.) | (−0.011, 0.123) | 0.090 | 0.668 | 0.645 | ||||

| Occupation 3 | 0.033 (n.s.) | (−0.052, 0.088) | 0.011 | 0.265 | 0.442 | ||||

| Tenure 4 | 0.076 (n.s.) | (−0.011, 0.147) | 0.024 | 0.887 | 0.746 | ||||

| H1 GM → G-OCB | 0.452 *** | (0.375, 0.523) | 0.082 | 13.271 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.252 | 0.546 | 0.342 |

| H2 GM → GIM | 0.491 *** | (0.407, 0.570) | 0.064 | 11.705 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.331 | 0.574 | 0.258 |

| H4 GM × GTL → GIM | 0.422 *** | (0.334, 0.501) | 0.042 | 9.529 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.288 | ||

| H5 GM × GTL → G-OCB | 0.376 *** | (0.275, 0.475) | 0.052 | 5.608 | 0.001 | Supported | 0.222 |

| Path | t-Value | BCCI | Path | t-Value | 95% BCCI | Decision | VAF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect GM → G-OCB | 0.749 | 11.428 | (0.653, 0.813) | Indirect effect GM → GIM → G-OCB | 0.297 | 7.321 | (0.234, 0.368) | Supported | 39.65% |

| Constructs | AVE | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| GM | 0.585 | |

| GTL | 0.535 | |

| GIM | 0.529 | 0.574 |

| G-OCB | 0.523 | 0.546 |

| Average scores | 0.543 | 0.560 |

| (GFI = ) | 0.551 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.; Rasheed, A.; Ayub, A. Does Green Mindfulness Promote Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065012

Chen C, Rasheed A, Ayub A. Does Green Mindfulness Promote Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065012

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Chunyan, Anmol Rasheed, and Arslan Ayub. 2023. "Does Green Mindfulness Promote Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065012

APA StyleChen, C., Rasheed, A., & Ayub, A. (2023). Does Green Mindfulness Promote Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability, 15(6), 5012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065012