Teacher Readiness and Learner Competency in Using Modern Technological Learning Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

3. Methodology

3.1. Theoretical Framework

3.2. Research Design

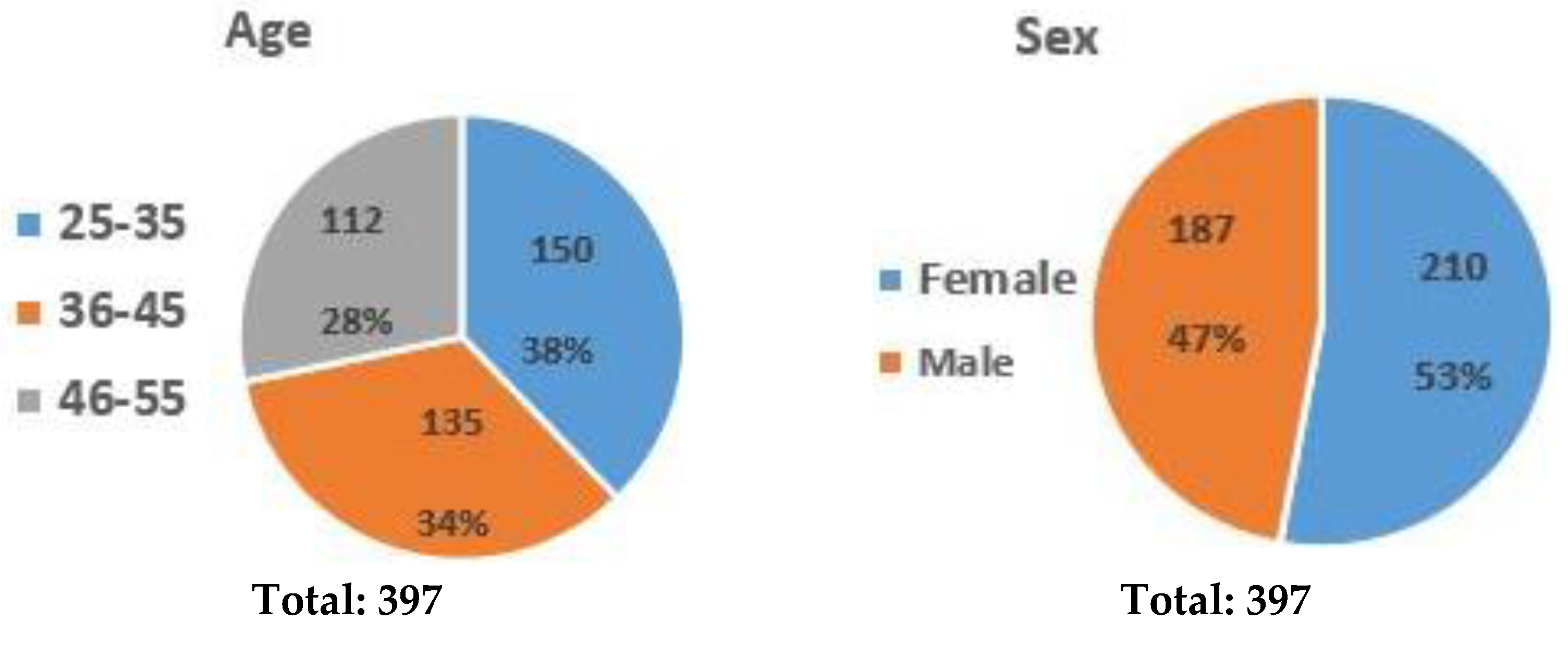

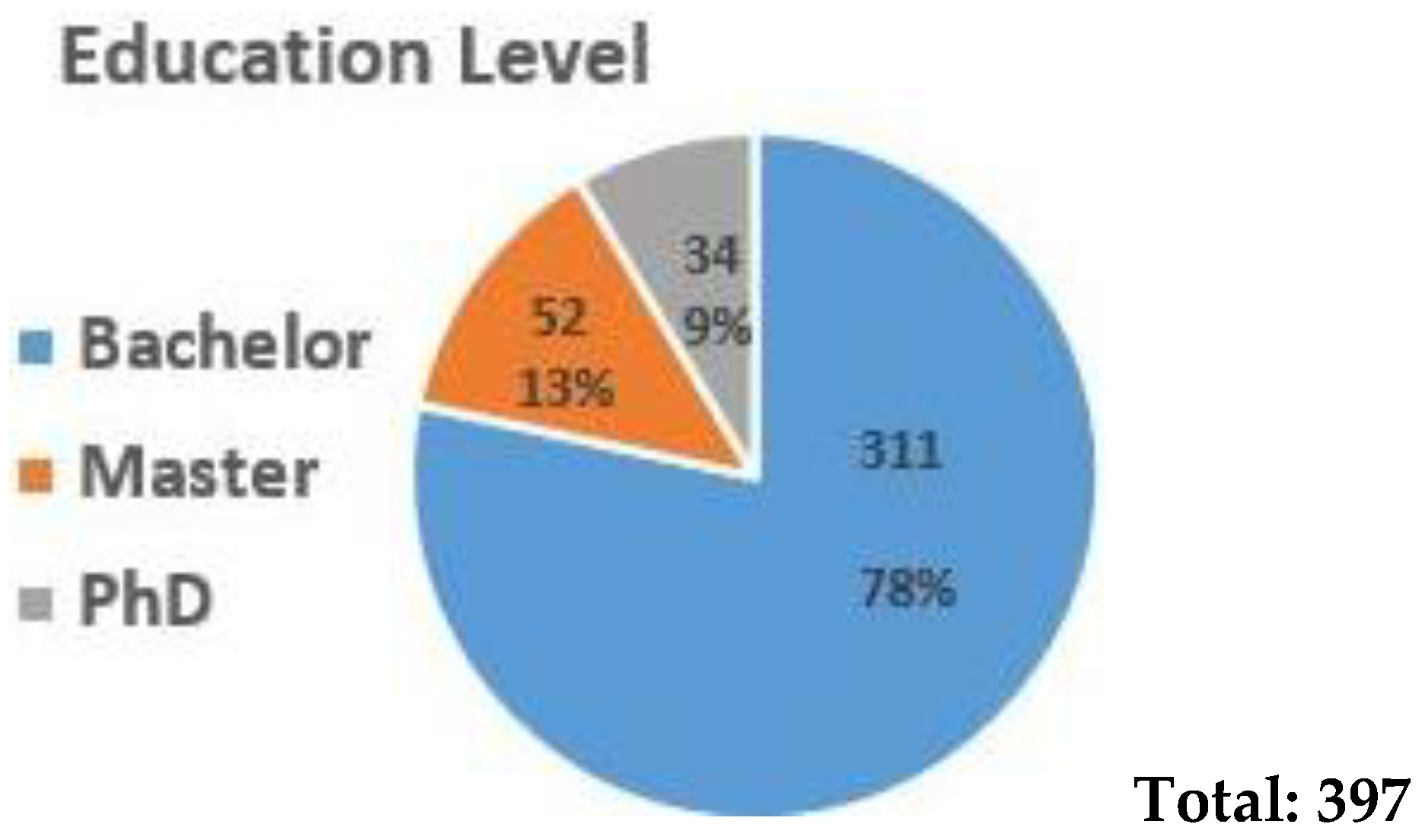

3.3. The Population and Sample

Criteria for Selecting the Sample

3.4. Tools for Data Collection

3.4.1. First Questionnaire

The Validity of the Questionnaire

Construct Validity

Questionnaire Stability

3.4.2. The Second Questionnaire

The Validity of the Questionnaire

Construct Validity

Questionnaire Stability

The Instrument of Data Analysis

- From 1.00 to 2.33 Low

- From 2.34 to 3.67 medium

- From 3.68 to 5.00 high

4. Findings

4.1. Result of the First Question

4.1.1. The First Domain: Beliefs

4.1.2. The Second Domain: Competencies

4.2. Results and Discussion of the Second Question:

4.2.1. Domain One: Academic Efficiency

4.2.2. Domain Two: Social Efficiency

4.3. Results and Discussion of the Third Question

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, C.J.H.; Padilla, A.M. Technology for Educational Purposes among Low-Income Latino Children Living in a Mobile Park in Silicon Valley: A Case Study before and During COVID-19. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, 42, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zou, D.; Xie, H.; Wang, F.L. Past, Present, and Future of Smart Learning: A Topic-Based Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, L.C. The Integration of Digital Devices into Learning Spaces According to the Needs of Primary and Secondary Teachers. TEM J. 2019, 8, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.; Eichhorn, K.; Prestridge, S.; Petko, D.; Sligte, H.; Baker, R.; Alayyar, G.; Knezek, G. Supporting Learning Leaders for the Effective Integration of Technology into Schools. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2018, 23, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassymova, G.; Akhmetova, A.; Baibekova, M.; Kalniyazova, A.; Mazhinov, B.; Mussina, S. E-Learning Environments and Problem-Based Learning. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 346–356. [Google Scholar]

- Baharuddin, B.; Dalle, J. Transforming learning spaces for elementary school children with special needs. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2019, 10, 344–365. [Google Scholar]

- Karra, S.; Alrashdan, H.; Wahby, C. The Contribution Level of Teacher-preparation Institutions (Colleges) in the Acquisition of Constructing Modern Technological Learning Spaces Skills: Relationship to Teaching Performance Level of Novice Teachers. Ilkogr. Online Elem. Educ. Online 2021, 20, 2187–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, R.; Nagasubramani, P. Impact of Modern Technology in Education. J. Appl. Adv. Res. 2018, 3, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, A.; Pinjani, A.; Bijani, A.; Yousuf, N. Challenges of Developing Competencies in Students in Developing Contexts. Lit. Inf. Comput. Educ. J. (LICEJ) 2019, 10, 3293–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, A.M.; Mocanu, C. Perceived Academic Self-Efficacy among Romanian Upper Secondary Education Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Santos, A. Learning Strategies and Academic Self-Efficacy In University Students: A Correlational Study. Psicol. Esc. E Educ. 2018, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippou, K. Students Academic Self-Efficacy in International Master’s Degree Programs In Finnish Universities. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2019, 31, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Handrianto, C.; Rasool, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Mustain, M.; Ilhami, A. Teachers Self-Efficacy and Classroom Management in Community Learning Centre (CLC) Sarawak. Spektrum J. Pendidik. Luar Sekol. (PLS) 2021, 9, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basith, A.; Syahputra, A.; Ichwanto, M.A. Academic Self-Efficacy as Predictor of Academic Achievement. JPI (J. Pendidik. Indones.) 2020, 9, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, B.; Váraljai, M.; Kollár, A.M. E-learning Spaces to Empower Students Collaborative Work Serving Individual Goals. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2020, 17, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.W.; Lingat, J.E.M.; Hollis, E.; Pritchard, M. Shifting Teaching and Learning in Online Learning Spaces: An Investigation of a Faculty Online Teaching and Learning Initiative. Online Learn. 2020, 24, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugaj, T.J.; Blohm, M.; Schmid, C.; Koehl, N.; Huber, J.; Huhn, D.; Herzog, W.; Krautter, M.; Nikendei, C. Peer-Assisted Learning (PAL): Skills Lab Tutors Experiences and Motivation. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluyol, Ç.; Şahin, S. Elementary School Teachers’ ICT Use in the Classroom and their Motivators for Using ICT. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, M.; Tsai, Y.M.; Klusmann, U.; Brunner, M.; Krauss, S.; Baumert, J. Students’ and Mathematics Teachers’ Perceptions of Teacher Enthusiasm and Instruction. Learn. Instr. 2008, 18, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavilova, T.; Isanova, N.; Ravshanova, T. Innovative Technologies, Role and Functions of the Teacher. Solid State Technol. 2020, 63, 11815–11821. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchi, F.; Voltolini, B. Europe, the Green Line and the Issue of the Israeli-Palestinian Border Closing the Gap between Discourse and Practice? Geopolitics 2018, 23, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A. 1967 Bypassing 1948: A Critique of Critical Israeli Studies of Occupation. Crit. Inq. 2018, 44, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuHussein, H.S.A. The Struggle for Land under Israeli Law: An Architecture of Exclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavifekr, S.; Rosdy, W.A.W. Teaching and Learning with Technology: Effectiveness of ICT Integration in Schools. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2015, 1, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemi, M.N.; Tahriri, A.; Zafarghandi, A.M. The Relationship between Classroom Environment and EFL Learners’ Academic Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2017, 5, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Reba, A.; Shahzad, A. A Comparative Study of Academic Self-Efficacy Level of Secondary School Students in Rural and Urban Areas of District Peshawar, Pakistan. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2021, 15, 754–761. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, S.S.; Faulkner, C.A. Research Methods for Social Workers: A Practice-Based Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–302. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnawi, M.; Najm, R. Readiness of Primary School Teachers in Government Schools in the Nablus Education Directorate To Employ E-Learning Competencies, Attitudes and Obstacles. J. Arab. Am. Univ. Res. 2019, 5, 102–138. [Google Scholar]

| Item No. | Correlation Coefficient with Field | Correlation Coefficient with the Tool | Item No. | Correlation Coefficient with Field | Correlation Coefficient with the Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.51 ** | 0.55 ** | 14 | 0.86 ** | 0.86 ** |

| 2 | 0.87 ** | 0.83 ** | 15 | 0.61 ** | 0.58 ** |

| 3 | 0.37 * | 0.36 * | 16 | 0.79 ** | 0.82 ** |

| 4 | 0.90 ** | 0.88 ** | 17 | 0.71 ** | 0.68 ** |

| 5 | 0.73 ** | 0.67 ** | 18 | 0.68 ** | 0.62 ** |

| 6 | 0.81 ** | 0.84 ** | 19 | 0.78 ** | 0.76 ** |

| 7 | 0.75 ** | 0.73 ** | 20 | 0.70 ** | 0.69 ** |

| 8 | 0.51 ** | 0.53 ** | 21 | 0.85 ** | 0.88 ** |

| 9 | 0.61 ** | 0.59 ** | 22 | 0.56 ** | 0.59 ** |

| 10 | 0.83 ** | 0.82 ** | 23 | 0.85 ** | 0.36 * |

| 11 | 0.67 ** | 0.69 ** | 24 | 0.46 * | 0.50 ** |

| 12 | 0.60 ** | 0.55 ** | 25 | 0.78 ** | 0.76 ** |

| 13 | 0.58 ** | 0.51 ** | 26 | 0.84 ** | 0.84 ** |

| Beliefs | Beliefs | Competencies | Teachers’ Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competencies | 1 | ||

| Teachers’ Readiness | 0.948 ** | 1 | |

| 0.985 ** | 0.989 ** | 1 |

| Domain | Replay Stability | Internal Consistency |

|---|---|---|

| Beliefs | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| Competences | 0.90 | 0.84 |

| Teachers’ Readiness | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| Item No. | Correlation Coefficient with Field | Correlation Coefficientwith the Tool | Item No. | Correlation Coefficient with Field | Correlation Coefficient with the Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.73 ** | 0.71 ** | 13 | 0.79 ** | 0.80 ** |

| 2 | 0.73 ** | 0.72 ** | 14 | 0.65 ** | 0.67 ** |

| 3 | 0.78 ** | 0.78 ** | 15 | 0.71 ** | 0.75 ** |

| 4 | 0.64 ** | 0.62 ** | 16 | 0.54 ** | 0.52 ** |

| 5 | 0.66 ** | 0.62 ** | 17 | 0.50 ** | 0.50 ** |

| 6 | 0.85 ** | 0.81 ** | 18 | 0.64 ** | 0.58 ** |

| 7 | 0.84 ** | 0.37 * | 19 | 0.79 ** | 0.78 ** |

| 8 | 0.84 ** | 0.82 ** | 20 | 0.78 ** | 0.81 ** |

| 9 | 0.86 ** | 0.84 ** | 21 | 0.60 ** | 0.53 ** |

| 10 | 0.59 ** | 0.59 ** | 22 | 0.61 ** | 0.52 ** |

| 11 | 0.74 ** | 0.72 ** | 23 | 0.83 ** | 0.85 ** |

| 12 | 0.77 ** | 0.79 ** | 24 | 0.57 ** | 0.55 ** |

| Domain | Academic Efficiency | Social Competence | Efficiency of Learners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Efficiency | 1 | ||

| Social Competence | 0.826 ** | 1 | |

| Efficiency of Learners | 0.883 ** | 0.910 ** | 1 |

| Domain | Replay Stability | Internal Consistency |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Efficiency | 0.86 | 0.75 |

| Social Competence | 0.83 | 0.71 |

| Efficiency of Learners | 0.85 | 0.82 |

| Rank | Serial Number | Domain | Mean | Standard Deviation | Level Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Beliefs | 2.96 | 0.793 | Medium |

| 2 | 2 | Competencies | 2.84 | 0.756 | Medium |

| Teachers’ Readiness | 2.89 | 0.758 | Medium |

| Rank | No. | Items | Mean | Standard Deviation | Level Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | I believe that technological learning spaces make learning fun and exciting for students. | 3.82 | 0.901 | High |

| 2 | 3 | I believe that technological learning spaces enhance students’ capabilities in the field of technology and keep pace with its developments. | 3.55 | 0.948 | Medium |

| 3 | 8 | I believe that technological learning spaces provide students with access to educational materials at any time. | 3.31 | 1.130 | Medium |

| 4 | 12 | I think that technological learning spaces provide flexibility for students to access educational materials from anywhere. | 3.16 | 1.260 | Medium |

| 5 | 10 | I believe that technological learning spaces contribute to increasing students’ culture, knowledge, and general awareness. | 2.94 | 1.319 | Medium |

| 6 | 4 | I believe that technological learning spaces provide channels of communication among students, teachers, and between the school and the parents of the students. | 2.92 | 1.245 | Medium |

| 7 | 9 | I believe that technological learning spaces increase students’ motivation to learn. | 2.74 | 1.161 | Medium |

| 8 | 2 | I believe that technological learning spaces contribute to improving student achievement. | 2.72 | 1.336 | Medium |

| 9 | 7 | I believe that the application of technological learning spaces works to raise the teacher’s technical and pedagogical competencies. | 2.65 | 1.210 | Medium |

| 10 | 5 | I believe that technological learning spaces develop students’ self-learning. | 2.59 | 1.387 | Medium |

| 11 | 6 | I believe that technological learning spaces enhance learning with diverse activities inside and outside the classroom through the application of their diverse forms. | 2.57 | 1.265 | Medium |

| 12 | 11 | I see that technological learning spaces provide continuous feedback to the parties involved in the educational process. | 2.52 | 1.053 | Medium |

| Beliefs | 2.96 | 0.793 | Medium |

| Rank | No. | Item | Mean | Standard Deviation | Degree Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | I have the ability to manage files on my computer, such as copying, pasting, and deleting files. | 3.45 | 1.172 | Medium |

| 2 | 18 | I can use YouTube to watch, learn, and download videos. | 3.34 | 1.103 | Medium |

| 3 | 23 | I can use email for correspondence and attaching files. | 3.30 | 1.082 | Medium |

| 4 | 13 | I can browse the web and download and upload files. | 3.27 | 1.116 | Medium |

| 5 | 15 | I have the ability to use social networks such as Facebook and Twitter. | 2.80 | 1.249 | Medium |

| 6 | 21 | I can use a word processor (MS Word). | 2.73 | 1.274 | Medium |

| 6 | 22 | I can use presentation software (MS Powerpoint). | 2.73 | 1.121 | Medium |

| 8 | 16 | I can search through search engines and do advanced searching on the Internet. | 2.67 | 1.414 | Medium |

| 9 | 19 | I have the basic skills to deal with the Windows system (Windows). | 2.60 | 1.138 | Medium |

| 10 | 14 | I possess theoretical knowledge within the framework of technological learning spaces. | 2.58 | 1.248 | Medium |

| 10 | 24 | I can use forums and chat sites on the Internet. | 2.58 | 1.381 | Medium |

| 12 | 25 | I can use the spreadsheet program (MS Excel). | 2.58 | 1.151 | Medium |

| 13 | 26 | I can use virtual classroom software on the Internet. | 2.57 | 1.239 | Medium |

| 14 | 20 | I can use chat programs (writing, audio, and video) on the Internet. | 2.52 | 1.072 | Medium |

| Competencies | 2.84 | 0.756 | Medium |

| Rank | No. | Domain | Mean | Standard Deviation | Degree Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Academic Efficiency | 3.21 | 0.733 | Medium |

| 2 | 2 | Social Efficiency | 3.20 | 0.715 | Medium |

| Learner Efficiency | 3.21 | 0.706 | Medium |

| Rank | No. | Item | Mean | Standard Deviation | Degree Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Students have the will to succeed academically. | 3.78 | 0.912 | High |

| 2 | 2 | Students can apply what they have learned outside the school. | 3.73 | 0.943 | High |

| 3 | 3 | Students have the ability to succeed in competitive academic assignments. | 3.72 | 1.038 | High |

| 4 | 7 | Students have the ability to submit their homework in a timely manner. | 3.56 | 1.166 | Medium |

| 5 | 9 | Students can identify the main points and ideas in the learning material. | 3.55 | 1.129 | Medium |

| 6 | 6 | Students have the ability to prepare well for exams. | 3.45 | 1.172 | Medium |

| 7 | 5 | Students can perform the required learning tasks. | 3.27 | 1.116 | Medium |

| 8 | 4 | Students have the ability to deal with challenging learning content. | 2.86 | 1.234 | Medium |

| 9 | 12 | Students can write articles and short reports independently. | 2.73 | 1.219 | Medium |

| 10 | 8 | Students have the ability to plan and organize their learning materials well. | 2.67 | 1.414 | Medium |

| 11 | 10 | Students can find information efficiently using various search engines. | 2.60 | 1.138 | Medium |

| 12 | 11 | Students can assess their learning outcomes independently. | 2.57 | 1.265 | Medium |

| Academic Efficiency | 3.21 | 0.733 |

| Rank | No. | Item | Mean | Standard Deviation | Degree Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | Students express their anger and frustration without hurting others. | 3.67 | 0.945 | Medium |

| 2 | 15 | Students do not panic easily about impulsive colleagues. | 3.66 | 1.071 | Medium |

| 3 | 24 | Students have the ability to communicate non-verbally. | 3.62 | 0.966 | Medium |

| 4 | 23 | Students adapt to each other regardless of the differences between them. | 3.60 | 1.079 | Medium |

| 5 | 17 | Students actively participate in activities. | 3.55 | 0.948 | Medium |

| 6 | 14 | Students defend their rights and needs in an appropriate manner. | 3.39 | 1.115 | Medium |

| 7 | 21 | Students are able to negotiate and reach a settlement on many matters. | 3.17 | 1.283 | Medium |

| 8 | 18 | Students participate in discussions and make a clear contribution to the discussion topic. | 2.96 | 1.311 | Medium |

| 9 | 13 | Students clearly express their desires, preferences, and their behavior. | 2.93 | 1.283 | Medium |

| 10 | 19 | Students adapt easily and quickly. | 2.72 | 1.336 | Medium |

| 11 | 20 | Students express their interest in others and request information from others. | 2.58 | 1.248 | Medium |

| 12 | 22 | Students do not draw attention to themselves. | 2.58 | 1.381 | Medium |

| Social Competence | 3.20 | 0.715 |

| Domain | Academic Efficiency | Social Competence | Efficiency of Learners | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belief | Correlation Coefficient R | 0.875 ** | 0.907 ** | 0.913 ** |

| Statistical Significance | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| The Number | 397 | 397 | 397 | |

| Competencies | Correlation Coefficient R | 0.930 ** | 895 ** | 0.935 ** |

| Statistical Significance | 000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| The Number | 397 | 397 | 497 | |

| Correlation Coefficient R | 0.922 ** | 0.918 ** | 0.942 ** | |

| Teachers’ Readiness | Statistical Significance | 000 | 000 | 000 |

| The Number | 397 | 397 | 397 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghalia, N.H.; Karra, S.Y. Teacher Readiness and Learner Competency in Using Modern Technological Learning Spaces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064928

Ghalia NH, Karra SY. Teacher Readiness and Learner Competency in Using Modern Technological Learning Spaces. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):4928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064928

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhalia, Nadia Hassan, and Sawsan Yousif Karra. 2023. "Teacher Readiness and Learner Competency in Using Modern Technological Learning Spaces" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 4928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064928

APA StyleGhalia, N. H., & Karra, S. Y. (2023). Teacher Readiness and Learner Competency in Using Modern Technological Learning Spaces. Sustainability, 15(6), 4928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064928