5.1. Principal Components Analysis

The matrix of Pearson correlations between the 21 variables revealed several interesting points (

Appendix A). First, the size of a club’s arena correlated with its past and present results, which shows the importance of infrastructure resources [

9]. Non-sporting salary expenditure correlated positively with a club’s revenues and sporting results. Variables associated with profitability correlated poorly with the other variables. Finally, travel costs represented a greater proportion of expenditure for clubs with poorer sporting results. This result may be because these clubs used travel expenses to complement salaries, as is the case in some amateur French football clubs [

19].

Results of the tests conducted to assess the quality of the PCA led us to discard one variable because of multicollinearity (Total Expenditure) and five variables for which KMOs were below 0.5 (% Other Products, % Public Sponsorship, % Sports Wages, % Private Sponsorship, % Sports Social Security Costs).

Table 3 shows the results of this backward induction process, which allowed us to improve the quality of the PCA [

43].

Consequently, we based our taxonomic analysis on the remaining 15 variables, which could be grouped into five dimensions with eigenvalues greater than one [

41]. These dimensions were D1: Exposure (most important variables: Ranking

t, Ranking

t − 1, TV Rights, Total Revenues); D2: Profitability (Operating Income, Net Income); D3: Professionalization (Wages + Social Security Costs); D4: Other Costs (Travel Costs, Other Costs); D5: Club’s History (Arena Size, Past Sporting Success, Subsidies, Equity). We applied a varimax rotation to facilitate the interpretation of these factors (i.e., reducing the number of variables with high loadings in each factor).

Appendix B shows the loadings of each variable on each dimension after this rotation. Considering differences between clubs on these five dimensions, rather than the 21 original variables, facilitated our analysis of the clusters identified by the taxonomic analysis.

5.2. Description of Clusters

Appendix C shows the results of the k-means analysis. Creating a fourth cluster greatly reduced the amount of intra-class variance.

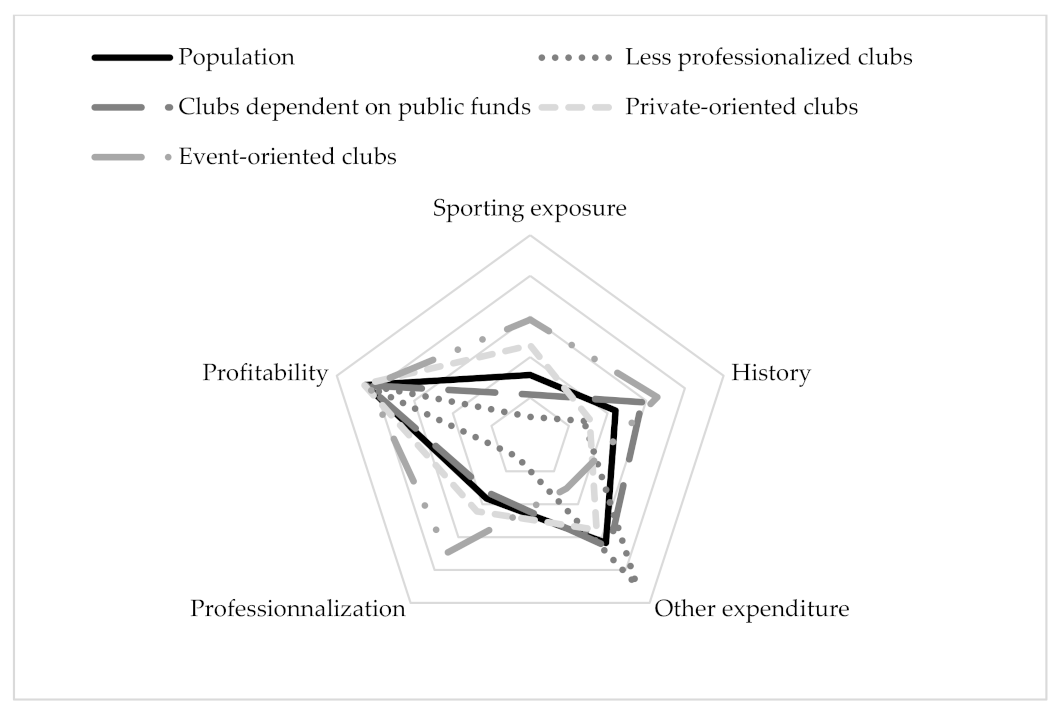

Figure 1 shows the profiles of the four clusters obtained by plotting the loadings of the variables for each of the five dimensions revealed by the PCA.

This diagram shows that the four economic models differ markedly in four of these dimensions. Although Pro A and Pro B clubs had an overall deficit (see

Table 1), there was no significant difference between clusters in overall profitability. The clubs in Clusters 2 and 4 had slightly higher mean deficits than the clubs in the other clusters, but intra-cluster heterogeneity was too great to use this dimension to explain the taxonomic analysis.

This cluster included the largest number of observations (131). Clubs in C1 had the lowest mean budgets (EUR 1.75 million) and the smallest arenas (2140 seats). Public subsidies were their main source of revenue (EUR 0.76 million, 43.68%), even though they received fewer subsidies than clubs in the other clusters. This low level of income was linked to mediocre sporting performance (lowest level of sporting success; mean performance equivalent to eighth place in Pro B; only 11% of observations were in Pro A). Clubs in this cluster also had the lowest level of professionalization (administrative payroll), which may be a cause or a consequence of their poor sporting performance.

However, C1 clubs spent more on travel costs (EUR 0.29 million) than the clubs in all the other clusters, even those in C4 (EUR 0.28 million), which take part in European competitions. Intriguingly, for 11 observations in C1, travel costs accounted for more than 40% of total expenditure.

In the case of Club 7, whose economic model evolved from C2 to C1 during our study period, the executive we interviewed underestimated the club’s expenditure on travel by 16% compared with the figures given in the club’s accounts (as provided by the DNCGCP). At the same time, the interviewee overestimated the amount the club spent on talent. The interviewee from Club 6, which was in C1 at the beginning of our analysis period, criticized some clubs’ accounting practices:

We are the only French basketball club that doesn’t use cash, so we don’t have a slush fund, something that’s very common, at least in basketball. I can’t talk about other sports, but I know that under-the-table payments are very common. And we don’t want to have any lost turnover.

C2 (94 observations) contains clubs that received substantial public subsidies, whether directly (mean subsidy = EUR 0.84 million) or indirectly in the form of arenas (mean size 4542 seats) and/or sponsorship. Indeed, public sponsorship accounted for 8.3% of these clubs’ revenues, compared with 2.8% in C1. This support may be explained by these clubs’ past sporting glory (only C4 clubs have a better track record). C2 clubs had a mean budget of EUR 2.4 million, which they appeared to invest in their sporting performance, as they achieved much better sporting results than C1 clubs (mean position of third place in Pro B, 36% of these clubs played in Pro A).

The quid pro quos of public sponsorship may be why clubs in C2 are more professionalized than those in C1 (administrative payroll of EUR 0.2 million in C2 vs. EUR 0.12 million in C1). Club 2 (representative of C2) does not differentiate between public and private partnerships, although its financial statements indicated that public sponsorship provided approximately 15% of its annual income. However, Club 7, which was in C2 for many years, highlighted the increasing demands being placed on clubs in exchange for public funding (without differentiating between subsidies and sponsorship):

We’re trying to find alternatives to the local authorities because we are aware that their contribution is going to decrease as time goes on. Even if it doesn’t, there’ll be strings attached; they won’t just sponsor elite sport. We’ll also have to have a societal mission.

Even though they lack an illustrious sporting past, clubs in this cluster managed to attract substantial sums from the private sector. Consequently, during our analysis period, C3 clubs (80 observations) obtained, on average, 43.7% of their revenues from private sponsorship. In contrast, only 12.4% of their revenues came from match-day receipts, an equivalent sum to C2 clubs, even though C3 clubs had much larger budgets (mean = EUR 4.69 million) and much smaller arenas (mean = 3417 seats) than C2 clubs. The income C3 clubs obtained from private sources compensated for the relatively modest amount of public support they received (C3 clubs obtained only 26.3% of their income from direct subsidies).

C3 clubs’ ability to attract private funding may be explained by their relatively high level of sporting success (equivalent to ninth place in Pro A; 86% of C3 clubs play in Pro A). This success may be linked to their high degree of professionalization, as reflected by their administrative payroll (EUR 0.47 million, wages plus social security contributions), which was twice as high as in C2. Having salaried staff may also have a direct effect on their ability to obtain private funding [

44].

This cluster contained 90 observations. C4 clubs had a mean budget of EUR 5.45 million and more diverse sources of revenue than clubs in the other clusters. In addition to the usual pillars of public subsidies (24% of income) and private and public sponsorship (48% of income: 41% from the private sector; 7% from the public sector), these clubs obtained a non-negligible proportion of their revenues from TV rights and match-day receipts (21% of total revenues, compared with 15% for C3 clubs).

These high match-related receipts are probably due to the fact that most C4 clubs took part in European competitions and had large enough arenas (mean capacity of 5999 seats) to obtain substantial ticketing revenues, especially for European Cup matches. Although competing in Europe incurs both high travel costs (EUR 0.28 million in C4 vs. EUR 0.16 million in C3) and the cost of organizing home games, the C4 clubs we interviewed did not remark on this, as they were used to taking part in European competitions. In contrast, our interviewees from C3 clubs (Clubs 5 and 6), which only occasionally qualify for these competitions, did comment on the cost of competing in Europe: “So, I know that in this model I have to achieve EUR 6.2 million in turnover in order to cover the cost of playing in Europe and to have a competitive team” (Club 5, member of C3 since 2015).

The race to recruit talented players seemed to be slightly less pronounced in C4 because sporting payroll (salaries and social security contributions) accounted for only 43% of C4 clubs’ expenditure, compared with 47% or 48% in the other three clusters. This limited ambition may explain why their domestic sporting performances were not much better than those of C3 clubs (mean position of eighth place in Pro A, 9% of C4 clubs play in Pro B) even though C4 clubs had far more resources.