Multidimensional Relative Poverty in China: Identification and Decomposition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Related Literature

2.1. Multidimensional Poverty

2.2. Relative Poverty

2.3. Multidimensional Relative Poverty

3. Measurement of Multidimensional Relative Poverty

3.1. Multidimensional Relative Poverty Index Measurement Method

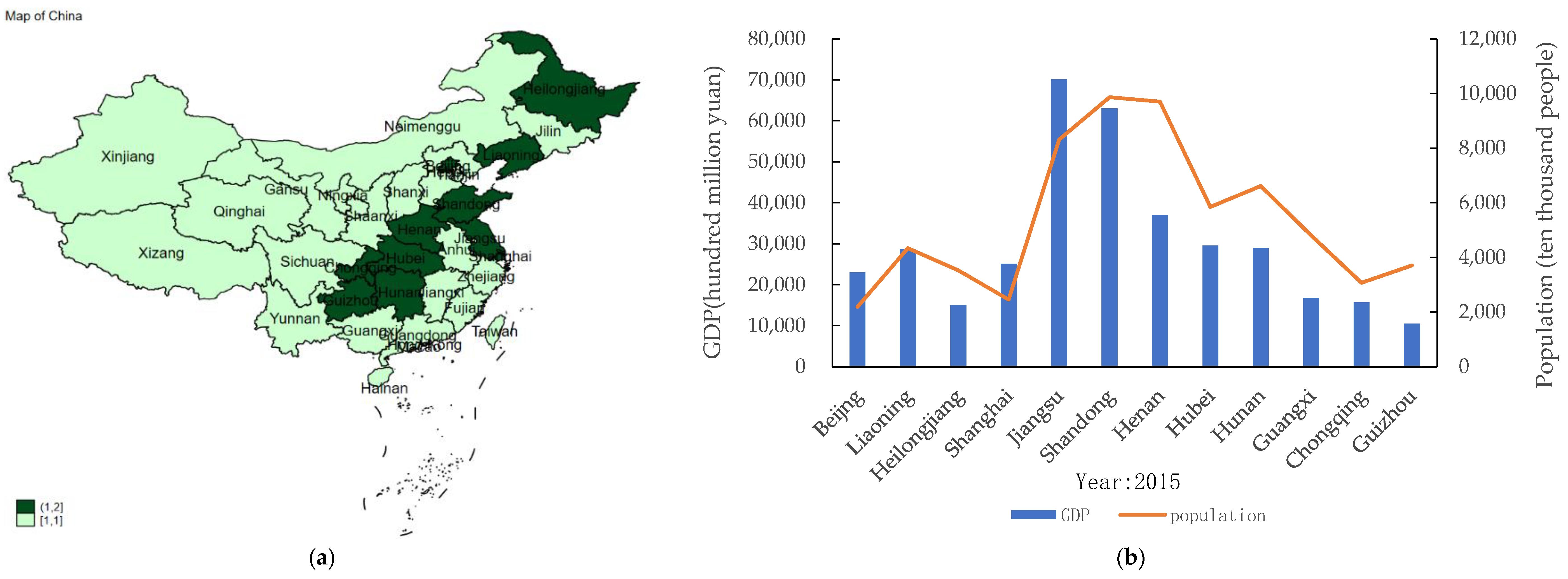

3.2. Data Source and Description

3.3. Construction of a Multidimensional Relative Poverty Index System

3.3.1. Income Dimension

3.3.2. Education Dimension

3.3.3. Health Dimensions

3.3.4. Living Standard Dimension

3.3.5. Employment Dimension

3.4. Relative Deprivation Cutoff

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Poverty Incidence of Each Dimensional Indicator

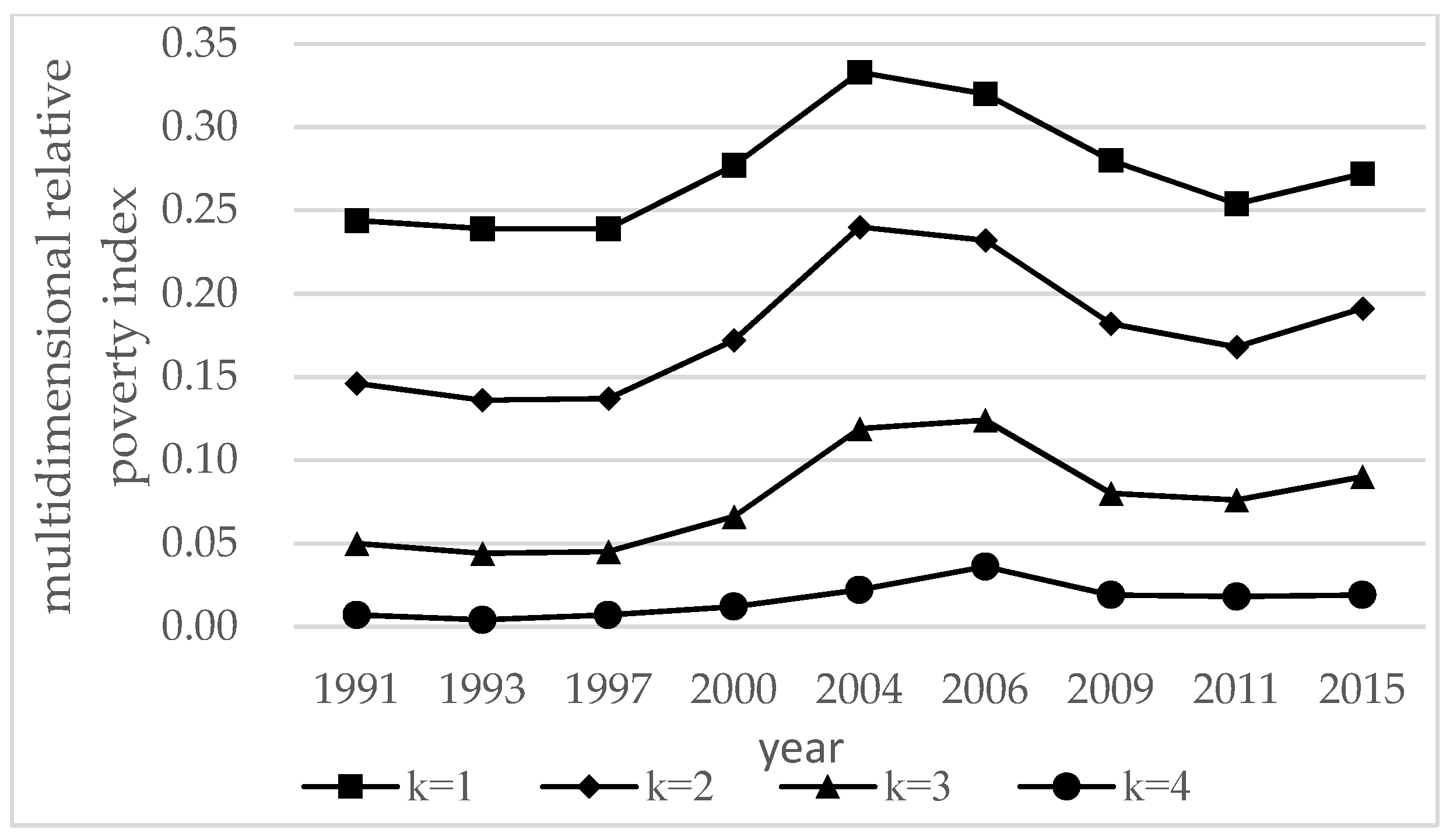

4.2. Measurement of Multidimensional Relative Poverty

4.3. Decomposition of the Multidimensional Relative Poverty Index ()

4.3.1. Decomposition by Sub-Indicator

4.3.2. Decomposition by Rural and Urban Areas

4.3.3. Decomposition by Region

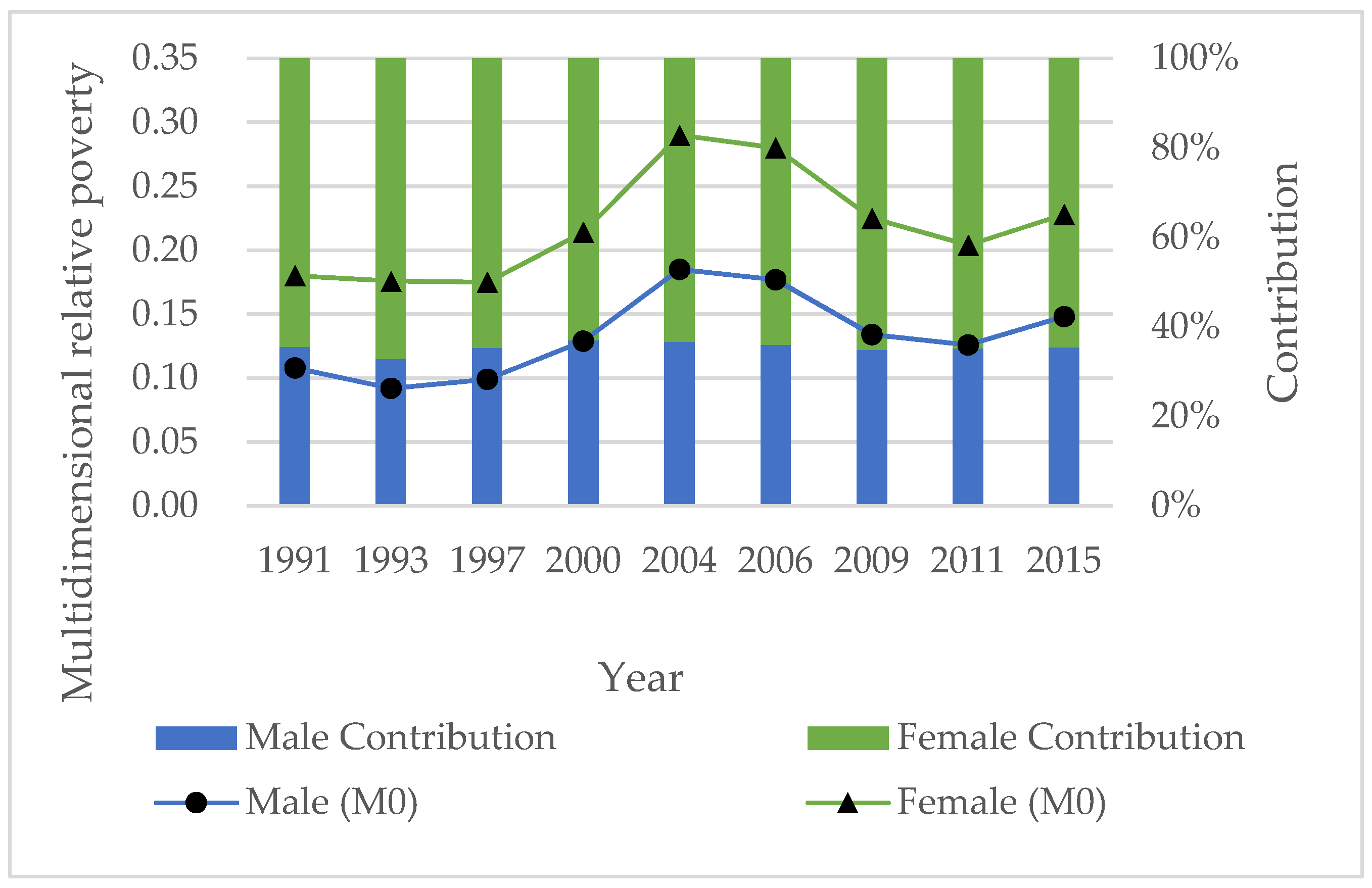

4.3.4. Decomposition by Gender

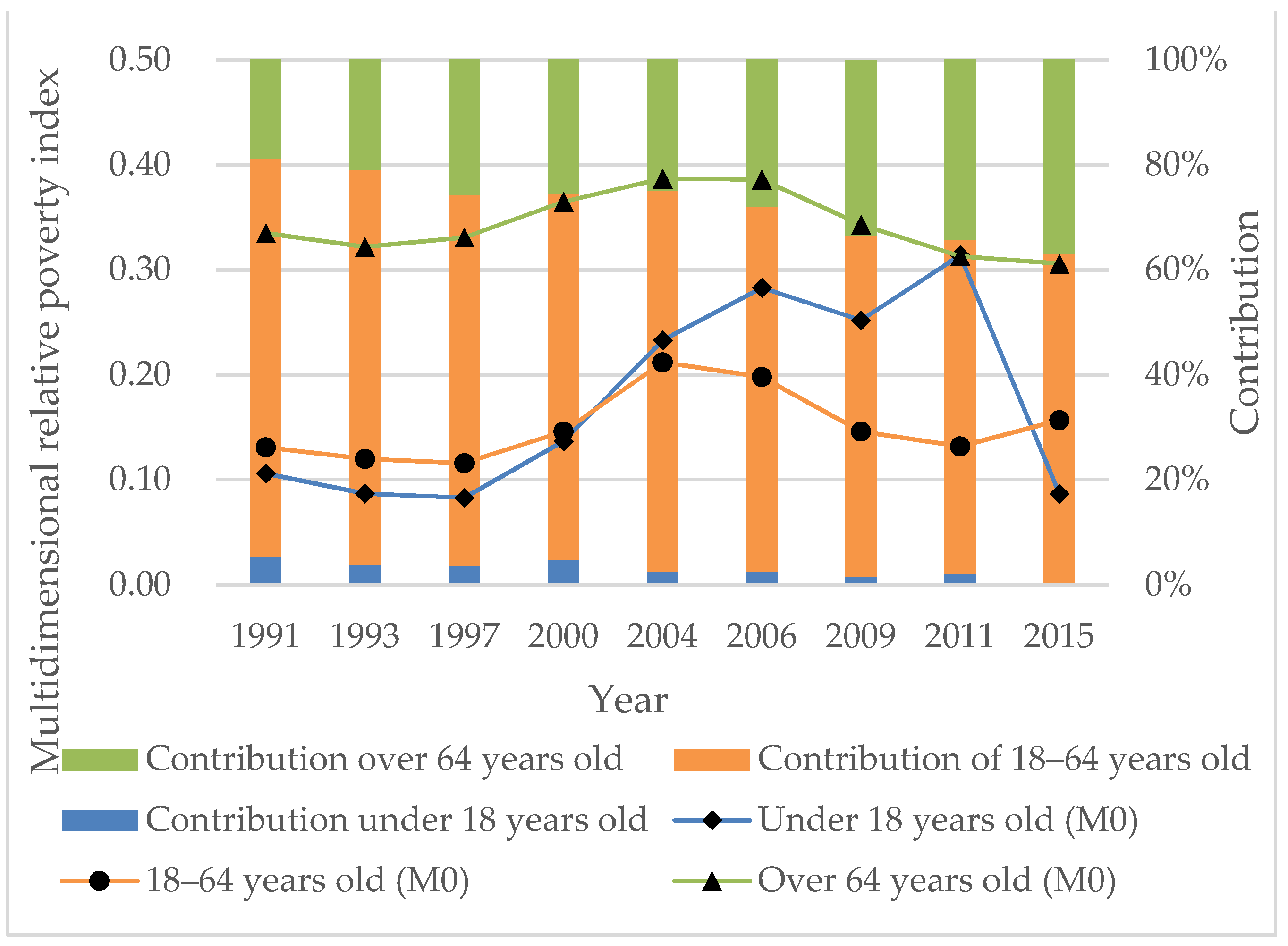

4.3.5. Decomposition by Age

4.4. Decomposition of Multidimensional Relative Poverty Changes

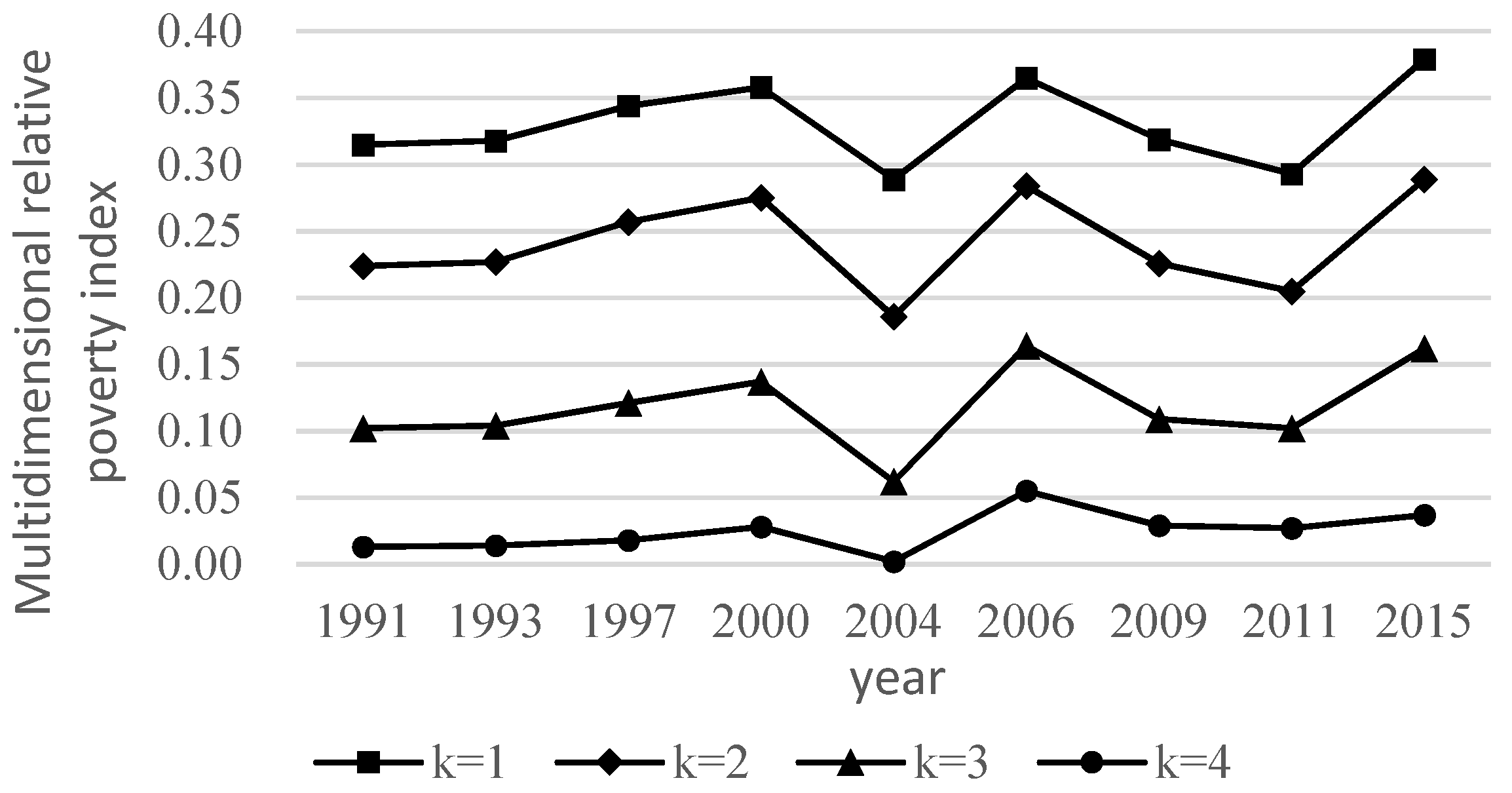

4.5. Robustness Test

4.5.1. Replacing the Indicator Weights

4.5.2. Replacing the Indicator Relative Deprivation Cutoff

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Poverty: An Ordinal Approach to Measurement. Econometrica 1976, 44, 219. Available online: https://are.berkeley.edu/courses/ARE251/fall2008/Papers/sen76.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Watts, H. An economic definition of poverty. In On Understanding Poverty; Moynihan, D.P., Ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 316–329. Available online: https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/dps/pdfs/dp568.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Hagenaars, A. A Class of Poverty Indices. Int. Econ. Rev. 1987, 28, 583–607. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2526568 (accessed on 12 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tsui, K.-Y. Multidimensional poverty indices. Soc. Choice Welf. 2002, 19, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.E.; Shorrocks, A.F. Subgroup consistent poverty indices. Econometrica 1991, 59, 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, F. The Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty. J. Econ. Inequal. 2003, 1, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M.E. Measuring Acute Poverty in the Developing World: Robustness and Scope of the Multidimensional Poverty Index. World Dev. 2014, 59, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, S. Eliminating poverty through development: The dynamic evolution of multidimensional poverty in rural China. Econ. Political Stud. 2022, 10, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchi, F.; Malerba, D.; Montenegro, C.E.; Rippin, N. Assessing Trends in Multidimensional Poverty during the MDGs. Rev. Income Wealth 2022, 68, S317–S346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xia, T. China’s Poverty Reduction Strategy and Post-2020 Relative Poverty Line Delineation—An Analysis Based on Theory, Policy and Data. China Rural. Econ. 2019, 10, 98–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, V. Redefining Poverty and Redistributing Income. Public Interest 1967, 8, 88–95. Available online: https://nationalaffairs.com/public_interest/detail/redefining-poverty-and-redistributing-income (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Atkinson, A.B. Poverty in Europe; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B. Statistical Inference for Poverty Measures with Relative Poverty Lines. J. Econ. 2001, 101, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Weakly Relative Poverty. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2011, 93, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Global Poverty Measurement When Relative Income Matters. J. Public Econ. 2019, 177, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yao, S.Q.; Song, S.T. Assessment of Weak Relative Poverty in China and Implications for Post-2020 Poverty Reduction Strategies. China Rural. Econ. 2021, 1, 72–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Lu, J. Measurement and Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Weak Relative Poverty in Rural and Urban China: 2012–2018. Popul. Econ. 2022, 1, 58–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Feng, H. Multidimensional relative poverty criteria in China after 2020: International experience and policy orientation. China Rural. Econ. 2020, 3, 2–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.; Wu, H.; Fan, J. Measurement and decomposition of multidimensional relative poverty of urban and rural households. Stat. Decis. 2021, 37, 68–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Shu, Y.; Cai, Z. Investigating the multidimensional relative poverty in China: Evidence from Nanling Yao ethnic group area. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, J. Relative Poverty Criteria, Measurement and Targeting in China after the Full Completion of Well-off Society—An Analysis Based on 2018 China Household Survey Data. China Rural. Econ. 2021, 3, 2–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Zhou, S. Research on multidimensional relative poverty measurement. Stat. Inf. Forum 2021, 36, 21–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Roche, J.M.; Vaz, A. Changes Over Time in Multidimensional Poverty: Methodology and Results for 34 Countries. World Dev. 2017, 94, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apablaza, M.; Yalonetzky, G. Decomposing Multidimensional Poverty Dynamics, Young Lives Working Paper 101. 2013. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/11797/Decomposing_Multidimensional-Poverty-Dynamics.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Roche, J.M. Monitoring progress in child poverty reduction: Methodological insights and illustration to the case study of Bangladesh. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorrocks, A.F. Decomposition procedures for distributional analysis: A unified framework based on the Shapley value. J. Econ. Inequal. 2012, 11, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP; OPHI. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2021—Unmasking Disparities by Ethnicity, Caste and Gender. United Nations Development Programme and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. 2021. Available online: https://ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/UNDP_OPHI_GMPI_2021_Report_Unmasking.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Bader, C.; Bieri, S.; Wiesmann, U.; Heinimann, A. A Different Perspective on Poverty in Lao PDR: Multidimensional Poverty in Lao PDR for the Years 2002/2003 and 2007/2008. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 126, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coromaldi, M.; Zoli, M. Deriving multidimensional poverty indicators: Methodological issues and an empirical analysis for Italy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 107, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlitz, J.-Y.; Apablaza, M.; Hoermann, B.; Hunzai, K.; Bennett, L. A multidimensional poverty measure for the Hindu Kush–Himalayas, applied to selected districts in Nepal. Mt. Res. Dev. 2015, 35, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanandita, W.; Tampubolon, G. Multidimensional Poverty in Indonesia: Trend Over the Last Decade (2003–2013). Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 128, 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Alkire, S. Multidimensional poverty measurement in China: Estimation and policy implications. China Rural. Econ. 2009, 12, 4–10+23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zou, W.; Fang, Y. A dynamic multidimensional study on poverty in China. China Popul. Sci. 2011, 6, 49–59+111. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Fang, Y. Dynamics of Multidimensional Poverty and Uni-dimensional Income Poverty: An Evidence of Stability Analysis from China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 25–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Q. Multidimensional methods and empirical application of poverty measurement in China. China Soft Sci. 2015, 7, 29–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Xia, Q. Analysis of the Relationship between Income Poverty and Multidimensional Poverty. Labor Econ. Res. 2015, 3, 38–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S. Synergies Among Monetary, Multidimensional and Subjective Poverty: Evidence from Nepal. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 125, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, M.L. Trends in Poverty in the United States 1967–1984. Rev. Income Wealth 1990, 36, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Monitoring Global Poverty: Report of the Commission on Global Poverty; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25141 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Yip, P.S.F.; Wong, J.H.K.; Li, B.Y.G.; Zhang, Y.; Kwok, C.L.; Ni Chen, M. Assessing the impact of population dynamics on poverty measures: A decomposition analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 134, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, F. The South African Labour Market: Theory and Practice, Revised, Revised 5th ed.; Van Schaik Publishers: Pretoria, South Africa, 2008; Available online: https://www.vitalsource.com/za/products/the-south-african-labour-market-revised-5th-f-barker-v9780627033384 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Vasishtha, G.; Mohanty, S.K. Spatial Pattern of Multidimensional and Consumption Poverty in Districts of India. Spat. Demogr. 2021, 9, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Seth, S. Multidimensional Poverty Reduction in India between 1999 and 2006: Where and How? World Dev. 2015, 72, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP; OPHI. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2022: Unpacking Deprivation Bundles to Reduce Multidimensional Poverty. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford. 2022. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/2022-global-multidimensional-poverty-index-mpi#/indicies/MPI (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Statistics South Africa. The South African MPI: Creating a Multidimensional Poverty Index Using Census Data; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-08/Report-03-10-082014.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Fransman, T.; Yu, D. Multidimensional poverty in South Africa in 2001–16. Dev. S. Afr. 2019, 36, 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhongde, S.; Haveman, R. Multi-Dimensional Deprivation in the U.S. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 133, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, B. Multidimensional deprivation in the United States; US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dhongde, S.; Pattanaik, P.K.; Xu, Y. Well-being, poverty, and the great recession in the U.S.: A study in a multidimensional framework. Rev. Income Wealth 2019, 65, S281–S306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhongde, S.; Haveman, R. Spatial and Temporal Trends in Multidimensional Poverty in the United States over the Last Decade. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 163, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, Q. Long-term multidimensional poverty, inequality and poverty-causing factors. Econ. Res. 2016, 51, 143–156. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J. Multidimensional Poverty in China: Findings Based on the CHNS. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Sabina, A.; Zhan, P. Measurement and decomposition of multidimensional poverty in China. Nankai Econ. Res. 2018, 5, 3–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension (Weight) | Indicator (Weight) | Indicators Deprived of Relative Cutoff |

|---|---|---|

| Income (1/5) | Annual household income per capita (1/5) | 50% of the median yearly household income per capita |

| Education (1/5) | Years of education (1/5) | The median number of years of schooling per year |

| Health (1/5) | Illness (1/15) | Sickness or injury |

| BMI (1/15) | BMI non-18.5–24 range | |

| Medical Insurance (1/15) | Not participating in health insurance | |

| Living standards (1/5) | Drinking water source (1/25) | The median of annual sample distribution (“other”, “ice or snow”, “creek, spring, river, lake”, “open well water (≤5 m)”, “groundwater (>5 m)”, “water plant”, “bottle water”) |

| Toilet type (1/25) | The median of annual sample distribution (“no bathroom”, “other”, “earth open pit”, “cement open pit”, “no flush, outside house, public restroom”, “flush, outside house, public restroom”, “no flush, in-house”, “flush, in-house”) | |

| Cooking fuel (1/25) | The median annual sample distribution (“other”, “wood, sticks/straw, etc”., “charcoal”, “kerosene”, “coal”, “liquefied gas”, “electricity”, “natural gas”) | |

| Transportation (1/25) | The median number of assets in the annual sample (“tricycles”, “bicycles (including electric-assist bicycles)”, “motorcycles (including three-wheeled motorcycles)”, “automobiles”) | |

| Household appliances (1/25) | The median number of assets of annual samples (“color TV”, “washing machine”, “refrigerator”, “air conditioner”, “sewing machine”, “electric fan”, “DVD/VCD”, “microwave oven”, “rice cooker”, “pressure cooker”, “telephone”, “cell phone (non-smart)”, “smartphone”, “satellite dish”, “Computer”, “tablet computer”) | |

| Employment (1/5) | Working situation (1/5) | No job (excluding students, retired, too young to work) |

| Dimension | Indicator | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Annual per capita household income (yuan) | 1390 | 1433 | 1862 | 2318 | 2852 | 3167 | 4706 | 6524 | 8533 |

| Education | Years of education | 6 years of elementary school | 6 years of elementary school | 6 years of elementary school | 2 years of junior high school | 3 years of junior high school | 3 years of junior high school | 3 years of junior high school | 3 years of junior high school | 3 years of junior high school |

| Health | Illness | Illness | Illness | Illness | Illness | Illness | Illness | Illness | Illness | Illness |

| BMI | <18.5 or >24 | <18.5 or >24 | <18.5 or >24 | <18.5 or >24 | <18.5 or >24 | <18.5 or >24 | <18.5 or >24 | <18.5 or >24 | <18.5 or >24 | |

| Medical Insurance | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | |

| Living standard | Drinking water source | Open well water (≤5 m) | Open well water (≤5 m) | Open well water (≤5 m) | Open well water (≤5 m) | Groundwater (>5 m) | Groundwater (>5 m) | Groundwater (>5 m) | Groundwater (>5 m) | Groundwater (>5 m) |

| Type of toilet | Cement open pit | Cement open pit | Cement open pit | Cement open pit | Flush, outside house, public restroom | No flush, in-house | Flush, in-house | Flush, in-house | Flush, in-house | |

| Cooking fuel | Coal | Coal | Coal | Coal | Coal | Liquefied gas | Liquefied gas | Electricity | Electricity | |

| Transportation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Household appliances | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Employment | Working situation | No job | No job | No job | No job | No job | No job | No job | No job | No job |

| Dimension | Indicator | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Annual per capita household income (yuan) | 19.97 | 20.86 | 20.05 | 24.18 | 24.44 | 26.32 | 23.54 | 24.28 | 26.65 |

| Education | Years of education | 45.17 | 43.02 | 41.11 | 48.64 | 47.88 | 45.07 | 45.36 | 39.40 | 35.70 |

| Health | Illness | 10.74 | 6.32 | 7.64 | 8.81 | 16.73 | 13.61 | 15.65 | 17.54 | 14.01 |

| BMI | 28.93 | 29.91 | 33.87 | 39.09 | 42.3 | 43.43 | 46.23 | 49.77 | 54.62 | |

| Medical Insurance | 68.87 | 73.76 | 75.28 | 78.44 | 72.61 | 50.18 | 8.91 | 4.91 | 2.58 | |

| Living standard | Drinking water source | 21.55 | 19.08 | 10.14 | 12.83 | 48.98 | 45.17 | 42.92 | 33.84 | 34.44 |

| Toilet type | 33.05 | 30.26 | 26.94 | 22.25 | 46.37 | 49.50 | 48.69 | 36.54 | 30.58 | |

| Cooking fuel | 38.07 | 39.21 | 37.52 | 28.85 | 25.27 | 49.88 | 34.37 | 45.50 | 44.00 | |

| Transportation | 17.37 | 16.15 | 21.83 | 21.32 | 25.78 | 28.02 | 26.99 | 27.46 | 28.36 | |

| Household appliances | 38.40 | 32.81 | 39.26 | 40.02 | 47.00 | 38.30 | 38.54 | 36.28 | 42.10 | |

| Employment | Working situation | 9.68 | 11.19 | 13.34 | 16.61 | 27.05 | 27.49 | 26.94 | 23.55 | 33.67 |

| Deprivation of Dimension | Year | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.578 | 0.573 | 0.572 | 0.636 | 0.705 | 0.671 | 0.622 | 0.563 | 0.580 | ||

| 0.422 | 0.417 | 0.417 | 0.436 | 0.473 | 0.477 | 0.45 | 0.452 | 0.469 | ||

| 0.244 | 0.239 | 0.239 | 0.277 | 0.333 | 0.320 | 0.28 | 0.254 | 0.272 | ||

| 0.267 | 0.248 | 0.25 | 0.305 | 0.41 | 0.388 | 0.312 | 0.285 | 0.321 | ||

| 0.547 | 0.547 | 0.55 | 0.563 | 0.585 | 0.598 | 0.583 | 0.587 | 0.596 | ||

| 0.146 | 0.136 | 0.137 | 0.172 | 0.24 | 0.232 | 0.182 | 0.168 | 0.191 | ||

| 0.073 | 0.064 | 0.065 | 0.094 | 0.165 | 0.171 | 0.111 | 0.104 | 0.124 | ||

| 0.682 | 0.678 | 0.694 | 0.697 | 0.719 | 0.725 | 0.721 | 0.727 | 0.727 | ||

| 0.050 | 0.044 | 0.045 | 0.066 | 0.119 | 0.124 | 0.080 | 0.076 | 0.098 | ||

| 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.025 | 0.042 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.022 | ||

| 0.856 | 0.851 | 0.845 | 0.851 | 0.889 | 0.863 | 0.859 | 0.851 | 0.843 | ||

| 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.022 | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.019 |

| Dimension | Indicator | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Annual per capita household income | 0.206 | 0.213 | 0.202 | 0.211 | 0.172 | 0.188 | 0.200 | 0.222 | 0.218 |

| Education | Years of education | 0.328 | 0.321 | 0.316 | 0.316 | 0.281 | 0.272 | 0.291 | 0.281 | 0.253 |

| Health | Illness | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.018 | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.030 | 0.023 |

| BMI | 0.046 | 0.052 | 0.054 | 0.056 | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.061 | 0.064 | 0.065 | |

| Medical insurance | 0.116 | 0.118 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.105 | 0.076 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.004 | |

| Living standard | Drinking water source | 0.029 | 0.022 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.046 | 0.042 | 0.040 | 0.035 | 0.032 |

| Type of toilet | 0.041 | 0.036 | 0.033 | 0.028 | 0.046 | 0.047 | 0.045 | 0.038 | 0.034 | |

| Cooking fuel | 0.040 | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.030 | 0.025 | 0.048 | 0.034 | 0.042 | 0.039 | |

| Transportation | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.027 | 0.023 | |

| Household appliances | 0.050 | 0.044 | 0.050 | 0.048 | 0.049 | 0.042 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.045 | |

| Employment | Working situation | 0.100 | 0.118 | 0.136 | 0.141 | 0.174 | 0.186 | 0.218 | 0.210 | 0.265 |

| Deprivation Dimension | Region | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban () | 0.147 | 0.153 | 0.163 | 0.187 | 0.221 | 0.218 | 0.185 | 0.152 | 0.145 | |

| Contribution | 0.197 | 0.187 | 0.197 | 0.189 | 0.204 | 0.209 | 0.205 | 0.251 | 0.214 | |

| Rural () | 0.291 | 0.274 | 0.269 | 0.312 | 0.383 | 0.366 | 0.322 | 0.328 | 0.357 | |

| Contribution | 0.803 | 0.813 | 0.803 | 0.811 | 0.796 | 0.791 | 0.795 | 0.749 | 0.786 | |

| Urban () | 0.075 | 0.080 | 0.090 | 0.105 | 0.140 | 0.143 | 0.114 | 0.089 | 0.081 | |

| Contribution | 0.168 | 0.172 | 0.189 | 0.171 | 0.179 | 0.19 | 0.194 | 0.222 | 0.170 | |

| Rural () | 0.180 | 0.158 | 0.157 | 0.198 | 0.284 | 0.271 | 0.212 | 0.225 | 0.265 | |

| Contribution | 0.832 | 0.828 | 0.811 | 0.829 | 0.821 | 0.810 | 0.806 | 0.778 | 0.830 | |

| Urban () | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.029 | 0.037 | 0.059 | 0.076 | 0.052 | 0.039 | 0.032 | |

| Contribution | 0.147 | 0.148 | 0.184 | 0.160 | 0.152 | 0.189 | 0.201 | 0.215 | 0.143 | |

| Rural () | 0.063 | 0.053 | 0.051 | 0.077 | 0.146 | 0.145 | 0.093 | 0.102 | 0.129 | |

| Contribution | 0.853 | 0.852 | 0.816 | 0.840 | 0.848 | 0.811 | 0.799 | 0.785 | 0.857 | |

| Urban () | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.023 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.004 | |

| Contribution | 0.179 | 0.167 | 0.249 | 0.140 | 0.106 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.186 | 0.095 | |

| Rural () | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.028 | 0.042 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 0.028 | |

| Contribution | 0.821 | 0.833 | 0.751 | 0.860 | 0.894 | 0.807 | 0.807 | 0.814 | 0.905 |

| Deprivation Dimension | Region | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern () | 0.204 | 0.208 | 0.214 | 0.226 | 0.272 | 0.261 | 0.218 | 0.172 | 0.187 | |

| Central () | 0.251 | 0.261 | 0.234 | 0.302 | 0.361 | 0.350 | 0.301 | 0.309 | 0.335 | |

| Western () | 0.285 | 0.248 | 0.269 | 0.296 | 0.370 | 0.354 | 0.332 | 0.325 | 0.329 | |

| Eastern Contribution | 0.297 | 0.308 | 0.218 | 0.252 | 0.278 | 0.279 | 0.268 | 0.293 | 0.287 | |

| Central Contribution | 0.373 | 0.394 | 0.466 | 0.478 | 0.457 | 0.450 | 0.459 | 0.379 | 0.395 | |

| Western Contribution | 0.330 | 0.298 | 0.316 | 0.271 | 0.265 | 0.271 | 0.273 | 0.328 | 0.318 | |

| Eastern () | 0.121 | 0.113 | 0.117 | 0.125 | 0.170 | 0.166 | 0.120 | 0.093 | 0.115 | |

| Central () | 0.148 | 0.156 | 0.135 | 0.202 | 0.275 | 0.265 | 0.204 | 0.217 | 0.249 | |

| Western () | 0.173 | 0.137 | 0.160 | 0.177 | 0.277 | 0.267 | 0.231 | 0.234 | 0.241 | |

| Eastern Contribution | 0.295 | 0.295 | 0.207 | 0.224 | 0.241 | 0.246 | 0.227 | 0.239 | 0.252 | |

| Central Contribution | 0.369 | 0.414 | 0.467 | 0.515 | 0.484 | 0.472 | 0.481 | 0.403 | 0.418 | |

| Western Contribution | 0.336 | 0.290 | 0.326 | 0.261 | 0.275 | 0.282 | 0.292 | 0.358 | 0.331 | |

| Eastern () | 0.040 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.040 | 0.071 | 0.079 | 0.044 | 0.036 | 0.052 | |

| Central () | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.043 | 0.086 | 0.147 | 0.146 | 0.096 | 0.103 | 0.120 | |

| Western () | 0.062 | 0.042 | 0.053 | 0.062 | 0.138 | 0.147 | 0.105 | 0.109 | 0.115 | |

| Eastern Contribution | 0.286 | 0.310 | 0.207 | 0.188 | 0.204 | 0.220 | 0.189 | 0.206 | 0.242 | |

| Central Contribution | 0.364 | 0.414 | 0.459 | 0.572 | 0.520 | 0.489 | 0.511 | 0.423 | 0.425 | |

| Western Contribution | 0.350 | 0.275 | 0.334 | 0.240 | 0.276 | 0.291 | 0.300 | 0.371 | 0.333 | |

| Eastern () | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.022 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.011 | |

| Central () | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.030 | 0.050 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.028 | |

| Western () | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.033 | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.020 | |

| Eastern Contribution | 0.301 | 0.285 | 0.250 | 0.141 | 0.207 | 0.210 | 0.170 | 0.204 | 0.244 | |

| Central Contribution | 0.429 | 0.570 | 0.481 | 0.607 | 0.575 | 0.569 | 0.496 | 0.393 | 0.481 | |

| Western Contribution | 0.271 | 0.145 | 0.269 | 0.251 | 0.218 | 0.221 | 0.334 | 0.403 | 0.275 |

| Deprivation Dimension | Gender | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male () | 0.202 | 0.193 | 0.195 | 0.234 | 0.283 | 0.270 | 0.232 | 0.212 | 0.231 | |

| Female () | 0.283 | 0.282 | 0.281 | 0.319 | 0.378 | 0.365 | 0.322 | 0.291 | 0.307 | |

| Male Contribution | 0.395 | 0.389 | 0.400 | 0.416 | 0.405 | 0.396 | 0.394 | 0.391 | 0.390 | |

| Female Contribution | 0.605 | 0.611 | 0.600 | 0.584 | 0.595 | 0.604 | 0.606 | 0.609 | 0.610 | |

| Male () | 0.108 | 0.092 | 0.099 | 0.129 | 0.185 | 0.177 | 0.134 | 0.126 | 0.148 | |

| Female () | 0.180 | 0.176 | 0.175 | 0.214 | 0.290 | 0.280 | 0.225 | 0.204 | 0.228 | |

| Male Contribution | 0.356 | 0.328 | 0.353 | 0.370 | 0.367 | 0.360 | 0.349 | 0.352 | 0.355 | |

| Female Contribution | 0.644 | 0.672 | 0.647 | 0.630 | 0.633 | 0.640 | 0.651 | 0.648 | 0.645 | |

| Male () | 0.033 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.046 | 0.080 | 0.087 | 0.055 | 0.050 | 0.064 | |

| Female () | 0.066 | 0.059 | 0.062 | 0.085 | 0.154 | 0.156 | 0.103 | 0.098 | 0.113 | |

| Male Contribution | 0.315 | 0.302 | 0.296 | 0.343 | 0.321 | 0.331 | 0.323 | 0.310 | 0.323 | |

| Female Contribution | 0.685 | 0.698 | 0.704 | 0.657 | 0.679 | 0.669 | 0.677 | 0.690 | 0.677 | |

| Male () | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.025 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.011 | |

| Female () | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.044 | 0.046 | 0.026 | 0.025 | 0.025 | |

| Male Contribution | 0.238 | 0.197 | 0.230 | 0.260 | 0.288 | 0.330 | 0.270 | 0.262 | 0.281 | |

| Female Contribution | 0.762 | 0.803 | 0.770 | 0.740 | 0.712 | 0.670 | 0.730 | 0.738 | 0.719 |

| Deprivation of Dimension | Age Group | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 18 years old () | 0.208 | 0.183 | 0.181 | 0.241 | 0.326 | 0.377 | 0.362 | 0.385 | 0.165 | |

| 18—64 years old () | 0.230 | 0.225 | 0.218 | 0.254 | 0.308 | 0.290 | 0.246 | 0.220 | 0.241 | |

| Over 64 years old () | 0.425 | 0.415 | 0.429 | 0.453 | 0.464 | 0.461 | 0.427 | 0.394 | 0.377 | |

| Contribution under 18 years old | 0.062 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.051 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.006 | |

| Contribution of 18–64 years old | 0.794 | 0.800 | 0.762 | 0.753 | 0.760 | 0.735 | 0.715 | 0.698 | 0.673 | |

| Contribution over 64 years old | 0.143 | 0.154 | 0.192 | 0.196 | 0.216 | 0.242 | 0.269 | 0.285 | 0.321 | |

| Under 18 years old () | 0.106 | 0.087 | 0.083 | 0.137 | 0.233 | 0.283 | 0.252 | 0.314 | 0.087 | |

| 18–64 years old () | 0.131 | 0.120 | 0.116 | 0.146 | 0.212 | 0.198 | 0.146 | 0.132 | 0.157 | |

| Over 64 years old () | 0.335 | 0.322 | 0.331 | 0.365 | 0.387 | 0.386 | 0.343 | 0.313 | 0.306 | |

| Contribution under 18 years old | 0.053 | 0.039 | 0.037 | 0.047 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.004 | |

| Contribution of 18–64 years old | 0.758 | 0.751 | 0.705 | 0.699 | 0.726 | 0.695 | 0.65 | 0.636 | 0.626 | |

| Contribution over 64 years old | 0.189 | 0.211 | 0.258 | 0.255 | 0.251 | 0.280 | 0.333 | 0.343 | 0.370 | |

| Under 18 years old () | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.054 | 0.115 | 0.144 | 0.158 | 0.191 | 0.015 | |

| 18–64 years old () | 0.041 | 0.035 | 0.032 | 0.046 | 0.094 | 0.091 | 0.052 | 0.047 | 0.062 | |

| Over 64 years old () | 0.163 | 0.145 | 0.156 | 0.203 | 0.253 | 0.277 | 0.205 | 0.194 | 0.186 | |

| Contribution under 18 years old | 0.036 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.048 | 0.024 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.002 | |

| Contribution of 18–64 years old | 0.696 | 0.677 | 0.601 | 0.581 | 0.646 | 0.599 | 0.526 | 0.502 | 0.522 | |

| Contribution over 64 years old | 0.305 | 0.295 | 0.371 | 0.370 | 0.330 | 0.377 | 0.450 | 0.470 | 0.476 | |

| Under 18 years old () | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.044 | 0.046 | 0.056 | 0 | |

| 18–64 years old () | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.02 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.010 | |

| Over 64 years old () | 0.050 | 0.036 | 0.044 | 0.064 | 0.067 | 0.112 | 0.069 | 0.058 | 0.049 | |

| Contribution under 18 years old | - | - | 0.015 | 0.027 | 0.014 | 0.024 | 0.029 | 0.034 | - | |

| Contribution of 18–64 years old | 0.376 | 0.272 | 0.326 | 0.339 | 0.509 | 0.455 | 0.329 | 0.376 | 0.394 | |

| Contribution over 64 years old | 0.624 | 0.728 | 0.659 | 0.635 | 0.478 | 0.521 | 0.642 | 0.590 | 0.606 |

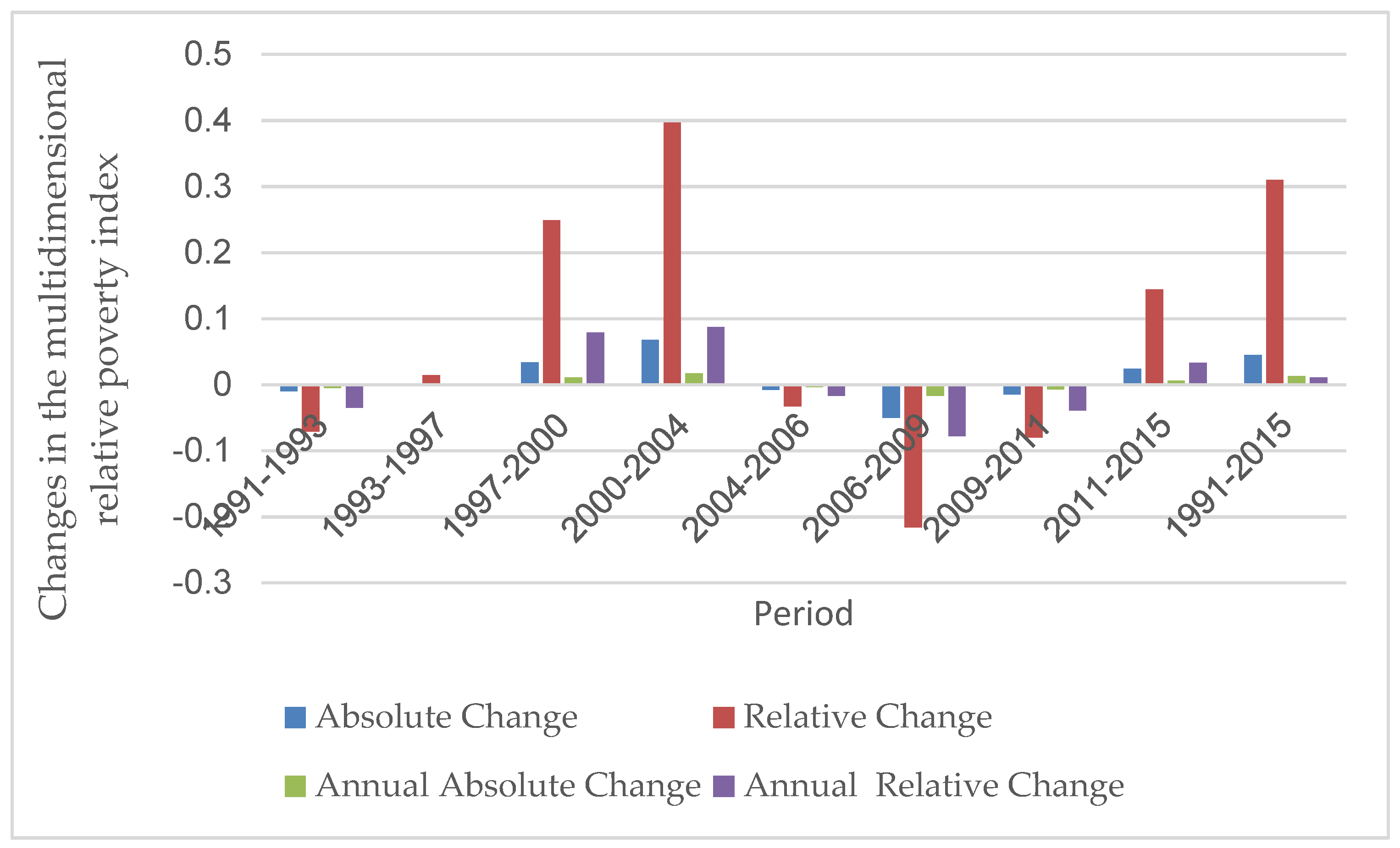

| Period | Absolute Change | Relative Change | Annual Absolute Change | Annual Relative Change | Poverty Incidence Effect | Intensity of Poverty Effect | Shapley Decomposition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poverty Incidence Effect Contribution | Intensity of Poverty Effect Contribution | |||||||

| 1991–1993 | −0.010 | −0.071 | −0.005 | −0.035 | −0.010 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| 1993–1997 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.595 | 0.405 |

| 1997–2000 | 0.034 | 0.249 | 0.011 | 0.079 | 0.031 | 0.004 | 0.895 | 0.105 |

| 2000–2004 | 0.068 | 0.397 | 0.017 | 0.087 | 0.060 | 0.008 | 0.885 | 0.115 |

| 2004–2006 | −0.008 | −0.033 | −0.004 | −0.017 | −0.013 | 0.005 | 1.663 | −0.663 |

| 2006–2009 | −0.050 | −0.216 | −0.017 | −0.078 | −0.045 | −0.005 | 0.895 | 0.105 |

| 2009–2011 | −0.015 | −0.080 | −0.007 | −0.039 | −0.016 | 0.001 | 1.082 | −0.082 |

| 2011–2015 | 0.024 | 0.144 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.021 | 0.003 | 0.886 | 0.114 |

| 1991–2015 | 0.045 | 0.310 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.031 | 0.014 | 0.682 | 0.318 |

| Deprivation Indicators | Year | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.914 | 0.924 | 0.946 | 0.957 | 0.970 | 0.965 | 0.949 | 0.945 | 0.953 | ||

| 0.330 | 0.317 | 0.314 | 0.324 | 0.398 | 0.393 | 0.343 | 0.326 | 0.331 | ||

| 0.302 | 0.293 | 0.297 | 0.310 | 0.386 | 0.379 | 0.326 | 0.308 | 0.315 | ||

| 0.770 | 0.787 | 0.804 | 0.830 | 0.881 | 0.862 | 0.821 | 0.799 | 0.816 | ||

| 0.375 | 0.357 | 0.354 | 0.360 | 0.429 | 0.429 | 0.382 | 0.369 | 0.371 | ||

| 0.289 | 0.281 | 0.284 | 0.298 | 0.378 | 0.370 | 0.314 | 0.295 | 0.303 | ||

| 0.616 | 0.618 | 0.612 | 0.646 | 0.756 | 0.736 | 0.661 | 0.617 | 0.638 | ||

| 0.423 | 0.405 | 0.408 | 0.410 | 0.469 | 0.471 | 0.431 | 0.425 | 0.424 | ||

| 0.260 | 0.250 | 0.249 | 0.265 | 0.355 | 0.347 | 0.285 | 0.262 | 0.270 | ||

| 0.456 | 0.439 | 0.430 | 0.453 | 0.610 | 0.587 | 0.490 | 0.444 | 0.462 | ||

| 0.476 | 0.459 | 0.465 | 0.469 | 0.517 | 0.522 | 0.486 | 0.484 | 0.481 | ||

| 0.217 | 0.201 | 0.200 | 0.212 | 0.315 | 0.306 | 0.238 | 0.215 | 0.222 | ||

| 0.303 | 0.262 | 0.265 | 0.282 | 0.463 | 0.436 | 0.326 | 0.292 | 0.304 | ||

| 0.532 | 0.523 | 0.528 | 0.533 | 0.565 | 0.577 | 0.548 | 0.546 | 0.542 | ||

| 0.161 | 0.137 | 0.140 | 0.150 | 0.262 | 0.251 | 0.178 | 0.160 | 0.165 | ||

| 0.168 | 0.130 | 0.138 | 0.152 | 0.301 | 0.297 | 0.188 | 0.170 | 0.174 | ||

| 0.595 | 0.592 | 0.595 | 0.600 | 0.625 | 0.633 | 0.616 | 0.612 | 0.608 | ||

| 0.100 | 0.077 | 0.082 | 0.091 | 0.188 | 0.188 | 0.116 | 0.104 | 0.106 | ||

| 0.065 | 0.048 | 0.054 | 0.063 | 0.164 | 0.173 | 0.096 | 0.083 | 0.084 | ||

| 0.673 | 0.671 | 0.673 | 0.676 | 0.691 | 0.697 | 0.684 | 0.681 | 0.675 | ||

| 0.044 | 0.032 | 0.036 | 0.043 | 0.113 | 0.120 | 0.066 | 0.057 | 0.056 | ||

| 0.021 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.070 | 0.080 | 0.037 | 0.031 | 0.029 | ||

| 0.750 | 0.747 | 0.751 | 0.754 | 0.764 | 0.767 | 0.759 | 0.756 | 0.747 | ||

| 0.016 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.053 | 0.061 | 0.028 | 0.024 | 0.022 | ||

| 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.029 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.006 | ||

| 0.844 | 0.840 | 0.851 | 0.833 | 0.840 | 0.838 | 0.840 | 0.831 | 0.827 | ||

| 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.005 | ||

| 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 0.919 | 0.932 | 0.920 | 0.909 | 0.921 | 0.916 | 0.923 | 0.909 | 0.909 | ||

| 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Deprivation Dimension | Year | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.694 | 0.695 | 0.741 | 0.751 | 0.681 | 0.721 | 0.671 | 0.618 | 0.751 | ||

| 0.454 | 0.458 | 0.465 | 0.477 | 0.424 | 0.506 | 0.476 | 0.473 | 0.505 | ||

| 0.315 | 0.318 | 0.344 | 0.358 | 0.289 | 0.365 | 0.319 | 0.293 | 0.379 | ||

| 0.402 | 0.405 | 0.456 | 0.479 | 0.349 | 0.465 | 0.380 | 0.342 | 0.467 | ||

| 0.556 | 0.560 | 0.564 | 0.573 | 0.533 | 0.612 | 0.595 | 0.600 | 0.619 | ||

| 0.224 | 0.227 | 0.257 | 0.275 | 0.186 | 0.284 | 0.226 | 0.205 | 0.289 | ||

| 0.150 | 0.153 | 0.175 | 0.194 | 0.092 | 0.222 | 0.149 | 0.140 | 0.220 | ||

| 0.682 | 0.681 | 0.695 | 0.705 | 0.675 | 0.736 | 0.729 | 0.730 | 0.738 | ||

| 0.102 | 0.104 | 0.121 | 0.137 | 0.062 | 0.164 | 0.109 | 0.102 | 0.162 | ||

| 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.063 | 0.033 | 0.031 | 0.043 | ||

| 0.860 | 0.863 | 0.866 | 0.868 | 0.871 | 0.870 | 0.859 | 0.855 | 0.848 | ||

| 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.018 | 0.028 | 0.002 | 0.055 | 0.029 | 0.027 | 0.037 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, W.; Cheng, X.; Fan, Z.; Yin, W. Multidimensional Relative Poverty in China: Identification and Decomposition. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064869

Zou W, Cheng X, Fan Z, Yin W. Multidimensional Relative Poverty in China: Identification and Decomposition. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):4869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064869

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Wei, Xiaopei Cheng, Zengzeng Fan, and Wenxi Yin. 2023. "Multidimensional Relative Poverty in China: Identification and Decomposition" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 4869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064869

APA StyleZou, W., Cheng, X., Fan, Z., & Yin, W. (2023). Multidimensional Relative Poverty in China: Identification and Decomposition. Sustainability, 15(6), 4869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064869