Addressing Agency Problem in Employee Training: The Role of Goal Congruence

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does training contribute to individual and organizational goals?

- Why do individuals and organizations make specific training choices?

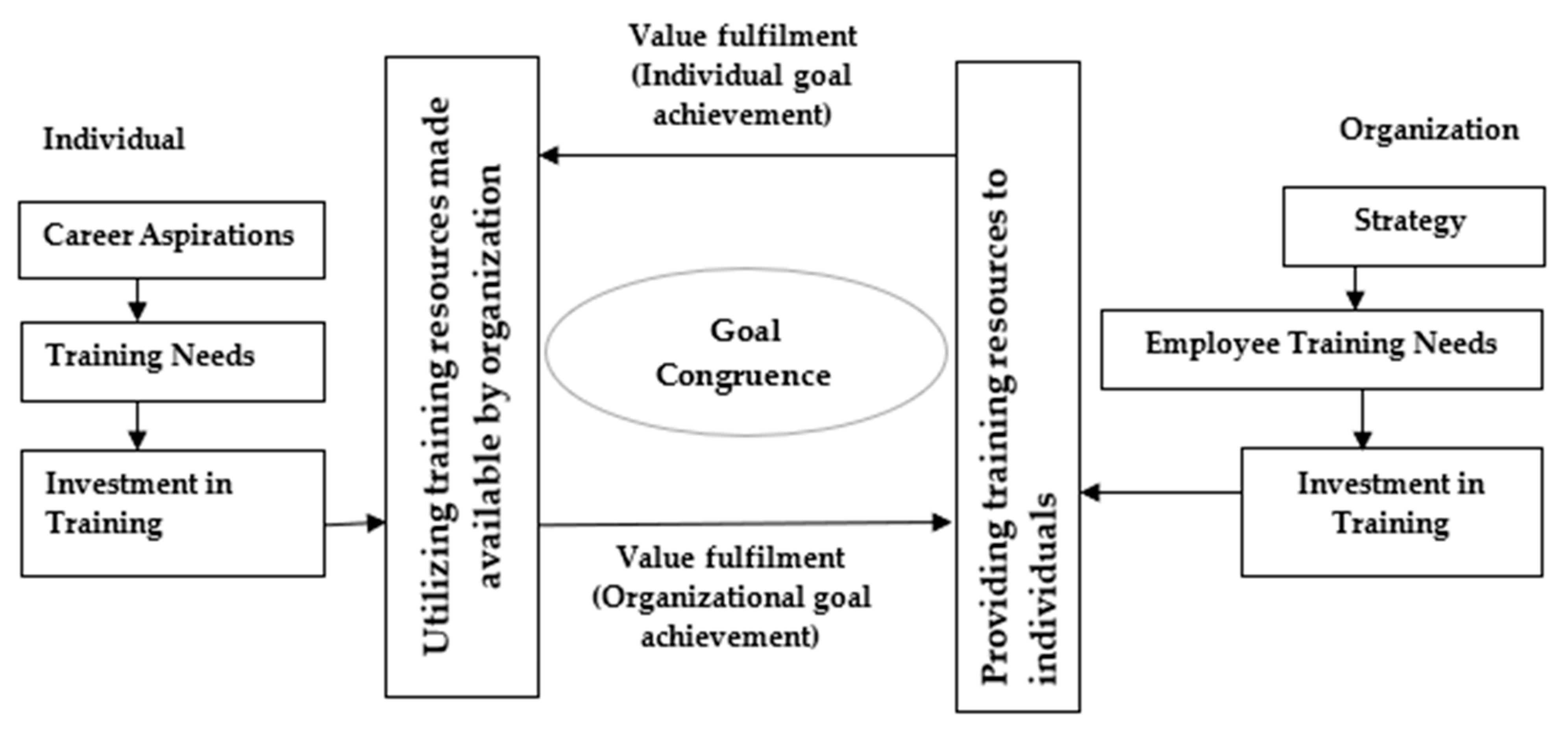

- How is the congruence of individual and organizational training goals achieved?

2. Theoretical Background

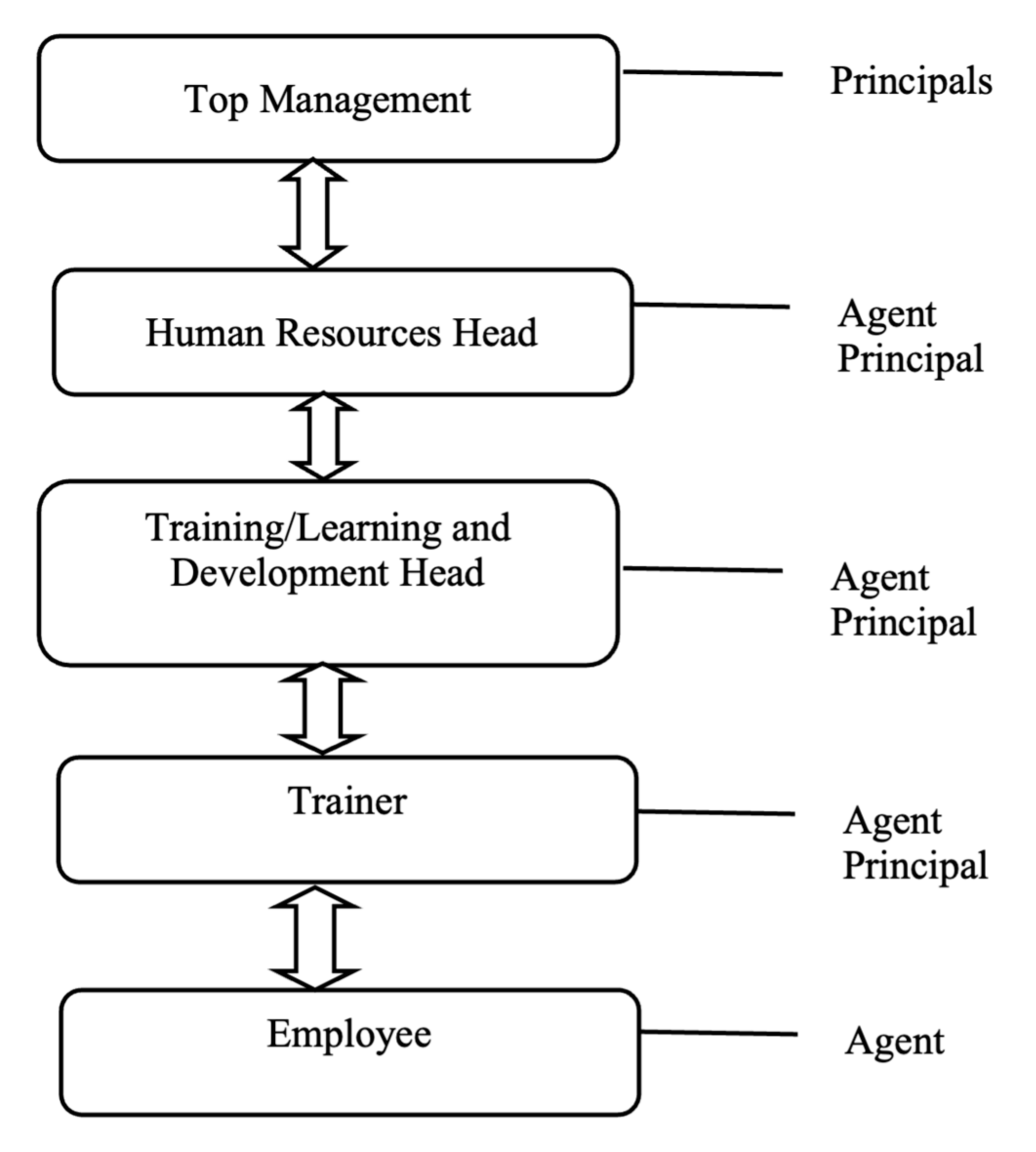

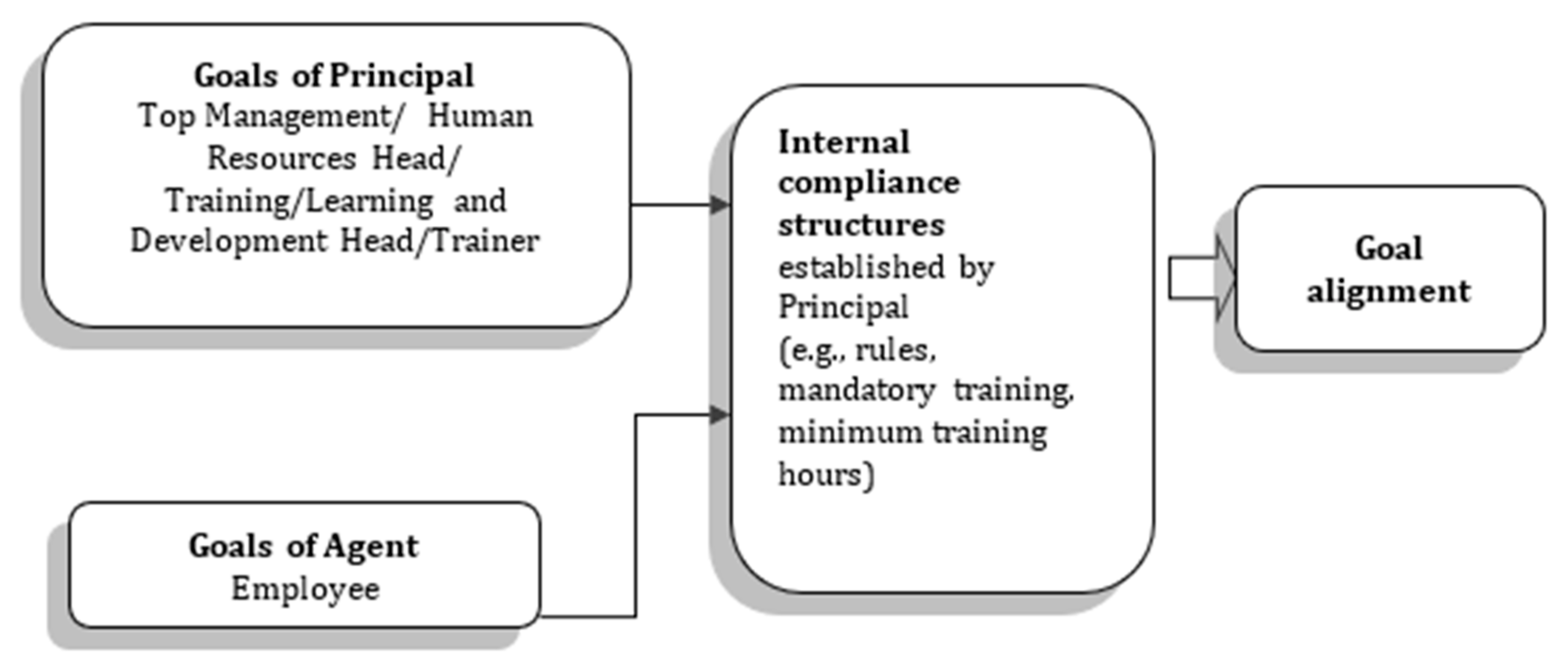

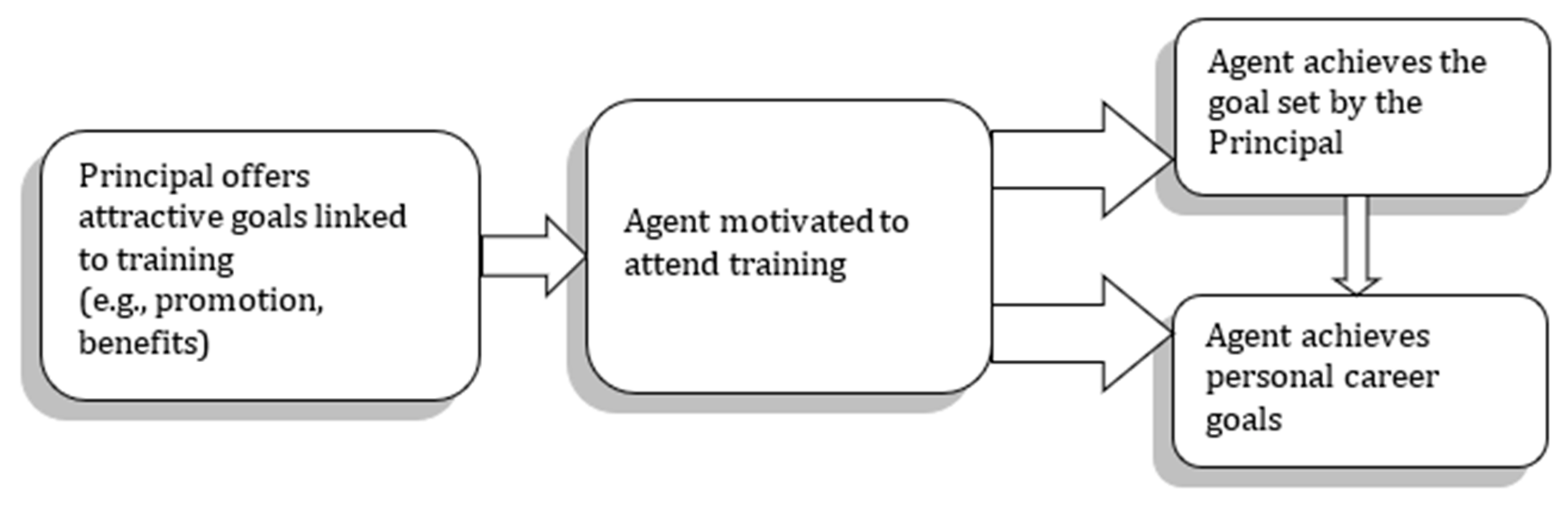

2.1. Agency Theory in Management and its Implications for Learning and Development

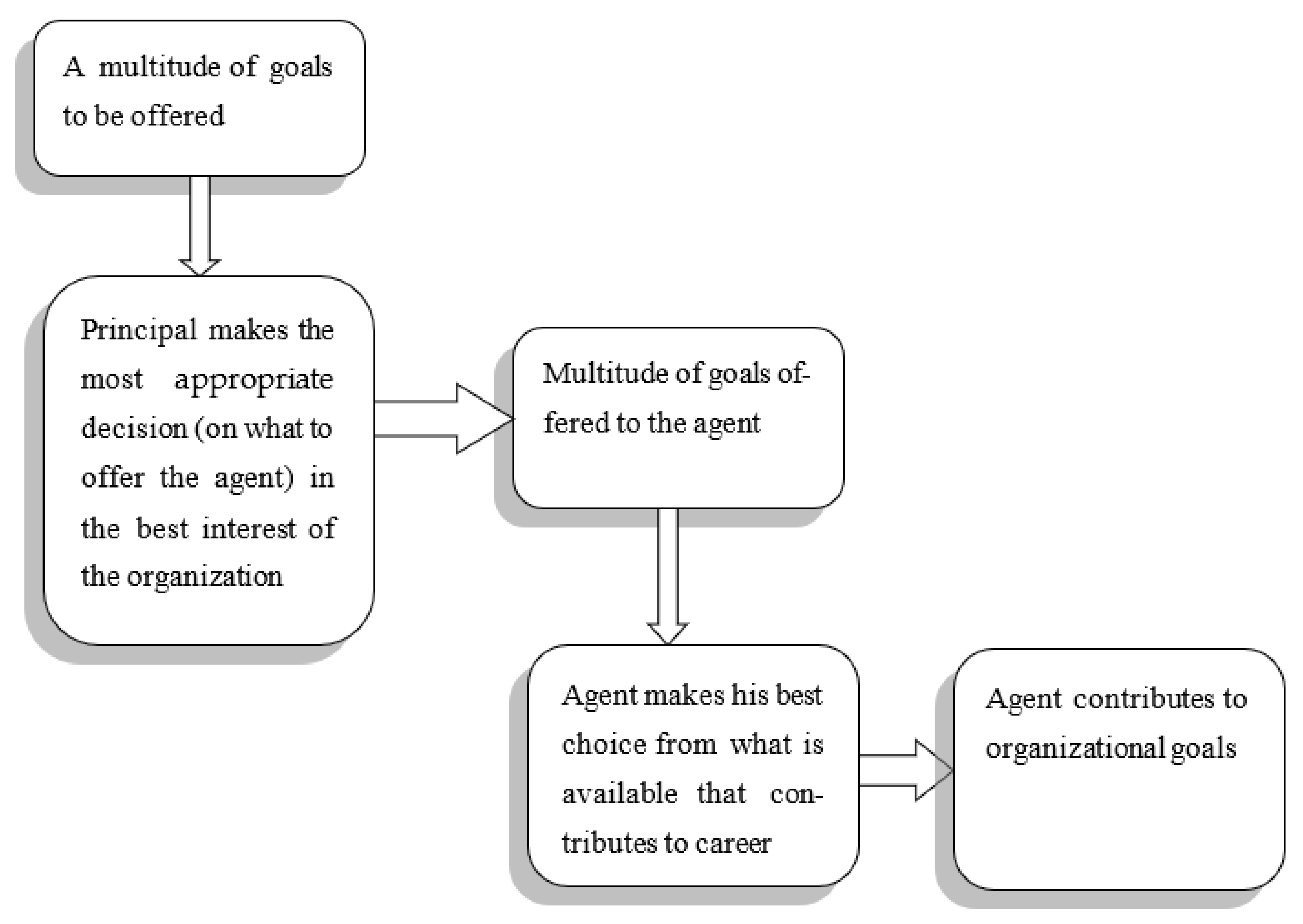

2.2. Individual and Organizational Goals

2.3. Training Motivation, Goal Choices and Bounded Rationality

3. Approach/Methodology

- How does employee learning happen in your organization?

- What are the challenges as far as learning is concerned?

- What are all the elements that motivate and attract people to participate in learning and development initiatives?

- How many learning decisions are made by the employees? When do you call training or learning effective?

4. Data Analysis

“We are structured in a way that we have separate focus groups on technology, industry, process leadership and culture. So, all of these give multiple options to learners. And they are again given avenues for creating learning paths required for their career outcomes.”

“[What is important is] how these learning opportunities incentivize them to grow within the organization. What is the learning path that they can take? Along with that, what kind of career options can they have?” one of the HR leaders who participated in our FGD opined.

“For teams that are outcome focused—teams such as research and development, leadership teams, strategy teams—their intrinsic motivation to learn is relatively higher because they have a much better visibility of how they would grow within the organization or the industry.”

“One key indicator of whether the training program was a success would be the people management score we will be getting in the employee satisfaction survey. So, we peg each of those programs to one of the outcomes. The clear indication of training success also reflects in the customer satisfaction scores taken after a specific period of time.”

“In an IT services industry, for the very core of survival, obviously learning is required. Because, if you see what we deliver to the customer hinges heavily on what we learn as an organization.”

“What kind of business strategies or objectives can we take or propose which will give us the edge over our competitors? So today, if you see, every other organization has a new strategy—yesterday it was agile, before that it was digital. Today we’re talking about virtual reality. Tomorrow it could be something else. Therefore, to be able to provide futuristic solutions to the customers, and to stay competitive beyond relevant, what kind of learning has to be implemented?”

“We give the [client] organization the confidence that our people are the best with respect to the various practices, the technologies, tools, and all that. Proficiency, capability, competence with respect to our business needs—that would be how generally, across the organization, I would explain the importance of training programs.”

“We can actually see any dip in productivity, quality, and adjust the needs of the organization with respect to training, and provide feedback to the training organization as well as to the departments and the various functions to ensure that necessary capability of being built into the organization.”

“Even though democratic learning opportunities are available, people coming forward and getting motivated themselves—we have a gap there. That is where we need to have this carrot and stick mechanism to drive people from behind and then get them into the learning experience.”

“When different aspects of training are involved over a particular period of time, we design certification in a way that they feel as if they have really earned it.”

“There are specific certifications and other things which the organization is looking at which we need to actually get.”

“So, someone who completes the training, I mean certification—anyone who attempts a certification gets a bronze badge, irrespective of whether they scored or not. … and it progresses to silver, gold and platinum. So, there are four badges, and the score for those badges are designed, and decided based on the industry-expected competence for each role.”

“Another consideration is how these learning opportunities incentivize us to grow within the organization. What is the learning path that I can take? Along with that, what kind of career options I can have.”

“In fact, we have created a place where they could view how they can go from one role to another, and what are those skills, capabilities and competencies or proficiency level of these competencies that will help them to move to the next level or the level that they aspire.”

“There are a lot of benefits like if you attend these training programs, you can definitely show it in the resume that you have completed so many.”

“If somebody is doing a training program on his own, maybe he will be more interested in [topics related to] whatever he is currently doing. But we also need to see their future roles, and for that, I think we are actually providing some motivation with respect to doing some programs.”

“For example, in the machine learning area at the third level of depth or proficiency, I may need 20 people to work on three different projects which are coming. So, this information will be available to the associates, and the associates will be able to come and voluntarily pick those learning opportunities. We will publish the learning calendar—we have a global learning calendar—and the associates who are interested in that area will come forward and enroll in those learning programs, and then in the next 3 months’ time they will be able to go through the learning program and graduate themselves to that particular competency proficiency level required for further business.”

“We gave the learner their right to learn—democratizing learning is the kind of buzzword today. So with the help of learning experience platforms (LXPs) and learning and performance platforms (LPPs), democratizing the learning has definitely happened.”

“We have online training in (vendor name). I mean, all those are open to us. Based on our relevant topics and free time, we can keep accessing it. Most of the time in the training tracker, we get classroom training. We get it on a monthly basis [announcing that] certain topics will be conducted for particular job levels on these dates. So, once we get the intimation, we will go to our portal and nominate ourselves for that particular training.”

“Our learning management system—there have been multiple options before us. One is that we have some internally developed platforms. Like we ourselves have something called ‘to share the best’ where our people do repeated training. We have an audio-visual version which has been stored into a repository, and anyone can access it.”

5. Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Policy Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Implications for Employees/Individuals

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, M. Learning to Choose, Choosing to Learn: The Key to Student Motivation and Achievement; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, U.; Patterson, M.; Kelly, C.; Mair, J. Organizations driving positive social change: A review and an integrative framework of change processes. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1250–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Garg, P. Learning organization and work engagement: The mediating role of employee resilience. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1071–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Pekovic, S. Organizational configurations for sustainability and employee productivity: A qualitative comparative analysis approach. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 216–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivathanu, B.; Pillai, R. Smart HR 4.0—How industry 4.0 is disrupting HR. Hum. Resour. Manag. Int. Dig. 2018, 26, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachová, K.; Papula, J.; Stacho, Z.; Kohnová, L. External partnerships in employee education and development as the key to facing industry 4.0 challenges. Sustainability 2019, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniuk, S.; Caganova, D.; Saniuk, A. Knowledge and skills of industrial employees and managerial staff for the industry 4.0 implementation. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Luthra, S.; Joshi, S.; Kumar, A. Accelerating retail supply chain performance against pandemic disruption: Adopting resilient strategies to mitigate the long-term effects. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021, 34, 1844–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Mihai, L.S. An integrated framework on the sustainability of SMEs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, B.J.; Blankemeyer, M. Future work self and career adaptability in the prediction of proactive career behaviors. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 86, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Huang, C.K. Employee turnover intentions and job performance from a planned change: The effects of an organizational learning culture and job satisfaction. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 42, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.; Doherty, A.; McGraw, P. Managing People in Sport Organizations: A Strategic Human Resource Management Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G.; Prahalad, C.K. Competing for the future. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1994, 72, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System. 1996. Available online: https://hbr.org/2007/07/using-the-balanced-scorecard-as-a-strategic-management-system (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Floyd, S.W.; Wooldridge, B. Building Strategy from the Middle: Reconceptualizing Strategy Process; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, C.A.; Carneiro, J.; Esteves, F. Conceptualizing and measuring the “strategy execution” construct. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 105, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaraja, M.; Shuck, B. Exploring organizational alignment-employee engagement linkages and impact on individual performance: A conceptual model. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.M.; Ngo, H.Y. The HR system, organizational culture, and product innovation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2004, 13, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Gupta, R.; Bates, R. Influence of organizational learning culture on knowledge worker’s motivation to transfer training: Testing moderating effects of learning transfer climate. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 36, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secara, C.G. Role of Training Courses in Motivating Human Resources in the Nuclear Research Subsidiary of Pitesti. Sci. Bull. Econ. Sci. 2014, 13, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Sun, L.Y.; Dong, Y. Innovating via building absorptive capacity: Interactive effects of top management support of learning, employee learning orientation and decentralization structure. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Martineau, J.W. Individual and situational influences in training motivation. In Improving Training Effectiveness in Work Organizations; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2014; pp. 205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, W.-T. Effects of Training Framing, General Self-efficacy and Training Motivation on Trainees’ Training Effectiveness. Pers. Rev. 2006, 35, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, A.; King, E.; Hebl, M.; Levine, N. The impact of the method, motivation, and empathy on diversity training effectiveness. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, R.A.; Kodwani, A.D. Employee Training and Development, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.J. What Motivates Trainees. Train. Dev. J. 1990, 44, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C.S.; Dobbins, G.H.; Ladd, R.T. Exploratory Field Study of Training Motivation: Influence of Involvement, Credibility, and Transfer Climate. Group Organ. Manag. 1993, 18, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; LePine, J.A.; Noe, R.A. Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozionelos, N.; Lin, C.H.; Lee, K.Y. Enhancing the sustainability of employees’ careers through training: The roles of career actors’ openness and of supervisor support. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, P.A.; Keating, L.A.; Ashford, S.J. How being in learning mode may enable a sustainable career across the lifespan. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaddar, S.; Nargundkar, S.; Daley, M. Inter-organizational information sharing: The role of supply network configuration and partner goal congruence. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 174, 744–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancouver, J.B.; Millsap, R.E.; Peters, P.A. Multilevel analysis of organizational goal congruence. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Mohammad Rahman, Z.; Belausteguigoitia, I. Task conflict and employee creativity: The critical roles of learning orientation and goal congruence. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Managerial influences on intraorganizational information technology use: A Principal-agent model. Decis. Sci. 1998, 29, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonck, M.; Greenaway, R.; Kennedy-Behr, A.; Askew, E. Student experiences of learning in a technology-enabled learning space. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2019, 56, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyal, S.; Barnes, B. “Agency” as a red herring in social theory. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2001, 31, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.M. The agency of the principal-agent relationship: An opportunity for HRD. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2019, 21, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.A. The economic theory of agency: The principal’s problem. Am. Econ. Rev. 1973, 63, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications: A Study in the Economics of Internal Organization. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship. 1975. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1496220 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Holmstrom, B. Moral hazard in teams. Bell J. Econ. 1982, 13, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnas, J. The normative theories of business ethics: A guide for the perplexed. Bus. Ethics Q. 1998, 8, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaney, R.C.; Lederer, A.L. Information systems project management: An agency theory interpretation. J. Syst. Softw. 2003, 68, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, A.H.; Pfaff, D. Agency theory, performance evaluation, and the hypothetical construct of intrinsic motivation. Account. Organ. Soc. 2002, 27, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, D.I.; Kim, S.K. When do incentives work in channels of distribution? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayezi, S.; O’Loughlin, A.; Zutshi, A. Agency theory and supply chain management: A structured literature review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, H.J.; Gupta, A.K. Impact of agency risks and task uncertainty on venture capitalist–CEO interaction. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1618–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, K.G.; Kenis, P. Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 18, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Sutton, R.I. Organizational behavior: Linking individuals and groups to organizational contexts. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1993, 44, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. The role of competence-based trust and organizational identification in continuous improvement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2004, 19, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Chae, C.; Han, S.J.; Yoon, S.W. Conceptual organization and identity of HRD: Analyses of evolving definitions, influence, and connections. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2017, 16, 294–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, H.; Churchill, R.Q. The role of employee training and development in achieving organizational objectives: A study of Accra Technical University. Arch. Bus. Res. 2018, 6, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sahinidis, A.G.; Bouris, J. Employee perceived training effectiveness relationship to employee attitudes. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2008, 32, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipboye, R.L. The Emerald Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, P.N.; Thacker, J.; Anand Ram, V. Effective Training Systems, Strategies, and Practices; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, T.M. The new economics of organization. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 1984, 28, 739–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, R. The theory of principal and agent: Part 2. Bull. Econ. Res. 1985, 37, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, C.M. An application of principal agent theory to contractual hiring arrangements within public sector organizations. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2016, 6, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenson, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, S.W. The effects of electronic commerce on the structure of intermediation. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2000, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.E.; Akdere, M. Examining agency theory in training & development: Understanding self-interest behaviors in the organization. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2011, 10, 399–416. [Google Scholar]

- Sannikov, Y. A continuous-time version of the principal-agent problem. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2008, 75, 957–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palan, R. Competency Management; PPM: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2007; pp. 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fallucchi, F.; Coladangelo, M.; Giuliano, R.; William De Luca, E. Predicting employee attrition using machine learning techniques. Computers 2020, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.J. The political evolution of principal-agent models. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2005, 8, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.P.; Martindale, E.T. Increasing Employee Participation in Voluntary Training: Issues and Solutions; ACET Research Division, University of Memphis: Memphis, TN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krawiec, K.D. Organization Misconduct: Beyond the principal-Agent Model. Fla. State Univ. Law Rev. 2005, 32, 571–614. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, M.D. Connecting key stakeholders: Sustainable learning opportunities. Dev. Learn. Organ. Int. J. 2009, 23, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, A.R.; Docherty, P. Learning by Design: Building Sustainable Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. CSR for HR: A Necessary Partnership for Advancing Responsible Business Practices; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Phalet, K.; Andriessen, I.; Lens, W. How future goals enhance motivation and learning in multicultural classrooms. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Organizational Behavior; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E.A. Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1968, 3, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafagatova, A.; Van Looy, A. A conceptual framework for process-oriented employee appraisals and rewards. Knowl. Process Manag. 2021, 28, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M.S.; Holton, E.; Swanson, R. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bohren, J.A.; Hauser, D.N. Bounded Rationality and Learning: A Framework and a Robustness Result. 2017. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2968460 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Herling, R.W. Bounded rationality and the implications for HRD. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2003, 5, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Rationality as process and as product of thought. Am. Econ. Rev. 1978, 68, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B. Political factors in decision making and implications for HRD. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2003, 5, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-Royo, C.; Chiclana, F.; Herrera-Viedma, E. Functional representation of the intentional bounded rationality of decision-makers: A laboratory to study the decisions a priori. Mathematics 2022, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, C. Greening HRD: Conceptualizing the triple bottom line for HRD practice, teaching, and research. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2015, 17, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, P. Qualitative Data Analysis Using a Dialogical Approach; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Madill, A.; Sullivan, P. Mirrors, portraits, and member checking: Managing difficult moments of knowledge exchange in the social sciences. Qual. Psychol. 2018, 5, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.D.; Loiselle, C.G. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus group interviewing. Handb. Interview Res. Context Method 2002, 141, 159. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Taylor, J.; Eley, N.; McKenna, K. Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: Findings from a randomized study. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, I.L. Groupthink; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, J.M.; Moreland, R.L. Group Processes; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 419–465. [Google Scholar]

- Agar, M.; MacDonald, J. Focus groups and ethnography. Hum. Organ. 1995, 54, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R.; Wutich, A.; Ryan, G.W. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lindlof, T.R.; Taylor, B.C. Qualitative Communication Research Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, M.; Schellens, P.J. Focus groups or individual interviews?: A comparison of text evaluation approaches. Tech. Commun. 1998, 45, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger, F.N.; Lee, H.B. Foundations of Behavioral Research; Hardcourt College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, K.R. The relationship between training and organizational commitment: A study in the health care field. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2001, 12, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Pract. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzmann, T.; Ely, K. A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: What we know and where we need to go. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M. Modern Learning Environments; CORE Education: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dachner, A.M.; Ellingson, J.E.; Noe, R.A.; Saxton, B.M. The future of employee development. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 31, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegenfurtner, A.; Könings, K.D.; Kosmajac, N.; Gebhardt, M. Voluntary or mandatory training participation as a moderator in the relationship between goal orientations and transfer of training. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2016, 20, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.E.; Akdere, M. Agency theory: Implications for human resource development. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of the Academy of HRD (Asia Chapter), Bangkok, Thailand, 3–6 November 2008; Boonsathorn, W., Osman-Gani, A.M., Akaraborworn, C.T., Eds.; Academy of Human Resource Development: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2008; pp. 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, R.E.; Akdere, M. The economics of utility, agency theory, and human resource development. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2008, 10, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.B. Aligning Stockholder and Manager Interests. J. Compens. Benefits 2000, 16, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilakant, V.; Rao, H. Agency theory and uncertainty in organizations: An evaluation. Organ. Stud. 1994, 15, 649–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, E.J.; Westphal, J.D. The costs and benefits of managerial incentives and monitoring in large US corporations: When is more not better? Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.L.; Heracleous, L. Rethinking agency theory: The view from law. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 294–314. [Google Scholar]

- Barette, J.; Lemyre, L.; Corneil, W.; Beauregard, N. Organizational learning facilitators in the Canadian public sector. Int. J. Public Adm. 2012, 35, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, S.; Di Milia, L. Organisational support for employee learning. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper, N.; Notelaers, G.; De Witte, H. Transitioning between temporary and permanent employment: A two-wave study on the entrapment, the stepping stone and the selection hypothesis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaakobi, G.E. Effects of Early Employment Experiences on Anticipated Psychological Contracts. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, L.; Lyons, S. The market within: A marketing approach to creating and developing high-value employment relationships. Bus. Horiz. 2008, 51, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaile, A.; Sumilo, E. The needs that individuals and organizations seek to fulfil by contemporary employment agreements: The case of Latvia. Manag. Organ. Syst. Res. 2015, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Beale, D.; Hoel, H. Workplace Bullying and the Employment Relationship: Exploring Questions of Prevention, Control and Context. Work. Employ. Soc. 2011, 25, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyombi, C. A Response to the Challenges Posed by the Binary Divide between Employee and Self-employed. Int. J. Law Manag. 2015, 57, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E. The Effects of Relationship Bonds on Emotional Exhaustion and Turnover Intentions in Frontline Employees. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdere, M.; Azevedo, R. Agency theory from the perspective of human resource development. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2005, 5, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdere, M.; Azevedo, R.E. Organizational development, agency theory, and efficient contracts: A research agenda. In Proceedings of the Midwest Academy of Management 2005 Annual Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 5–10 August 2005; Moorman, R.H., Kruse, K.D., Eds.; Midwest Academy of Management: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Akdere, M.; Azevedo, R.E. Agency theory implications for efficient contracts in organization development. Organ. Dev. J. 2006, 24, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Akdere, M.; Yilmaz, T. Team performance-based compensation plans: Implications for human resources and quality improvement from agency theory perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2006, 6, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, E.F., III; Naquin, S. A critical analysis of HRD evaluation models from a decision-making perspective. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2005, 16, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, C. The Functions of Executive; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A.; Lal, R.; Srinivasan, V.; Staelin, R. Sales force compensation plans: An agency theoretic perspective. Mark. Sci. 1985, 4, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Tosi, H.; Hinkin, T. Managerial control, performance, and executive compensation. Acad. Manag. J. 1987, 30, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalo, S. When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Get Incentives. Pharm. Exec. 2003, 23 (Suppl. 5), 8–11. [Google Scholar]

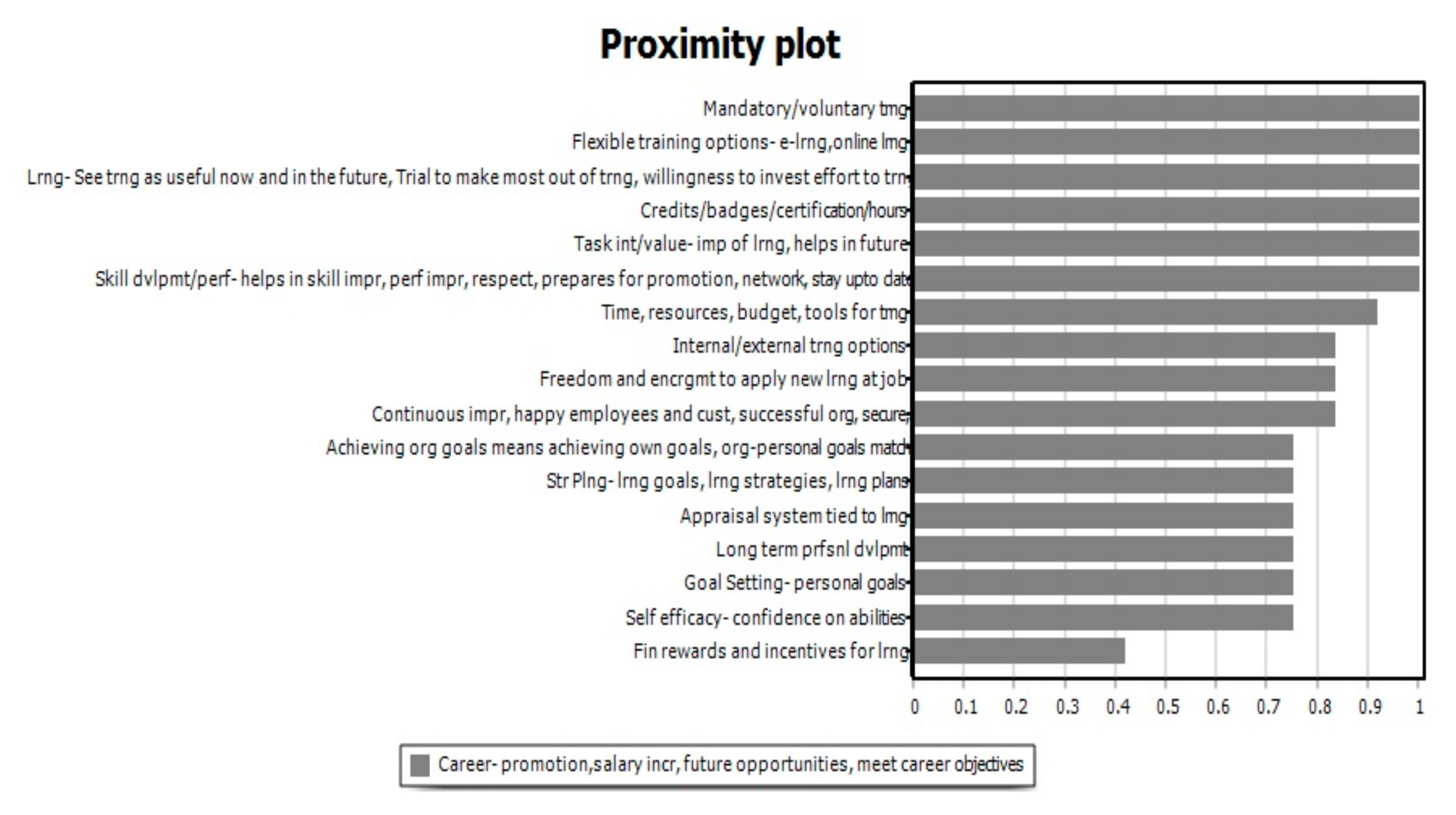

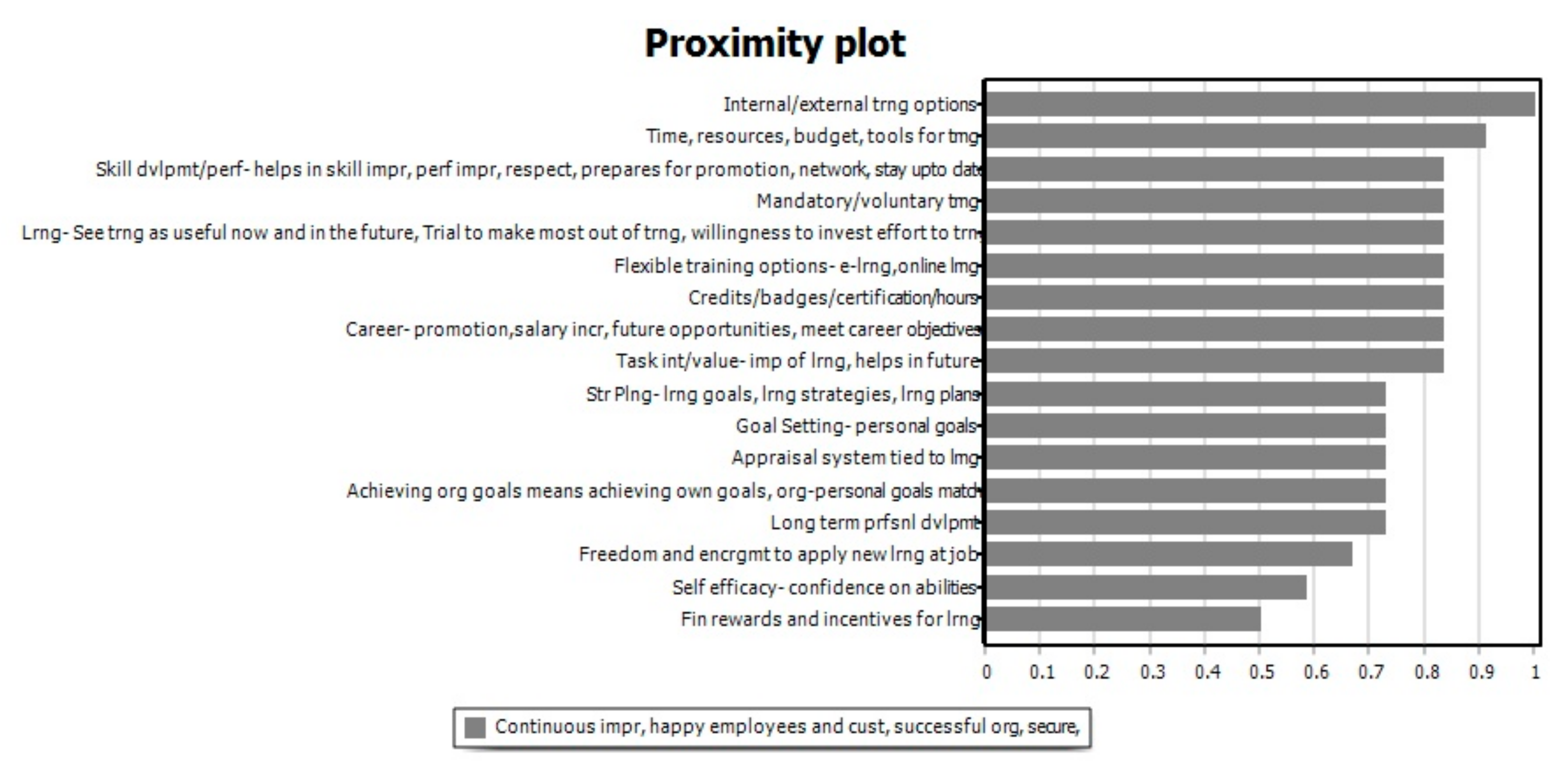

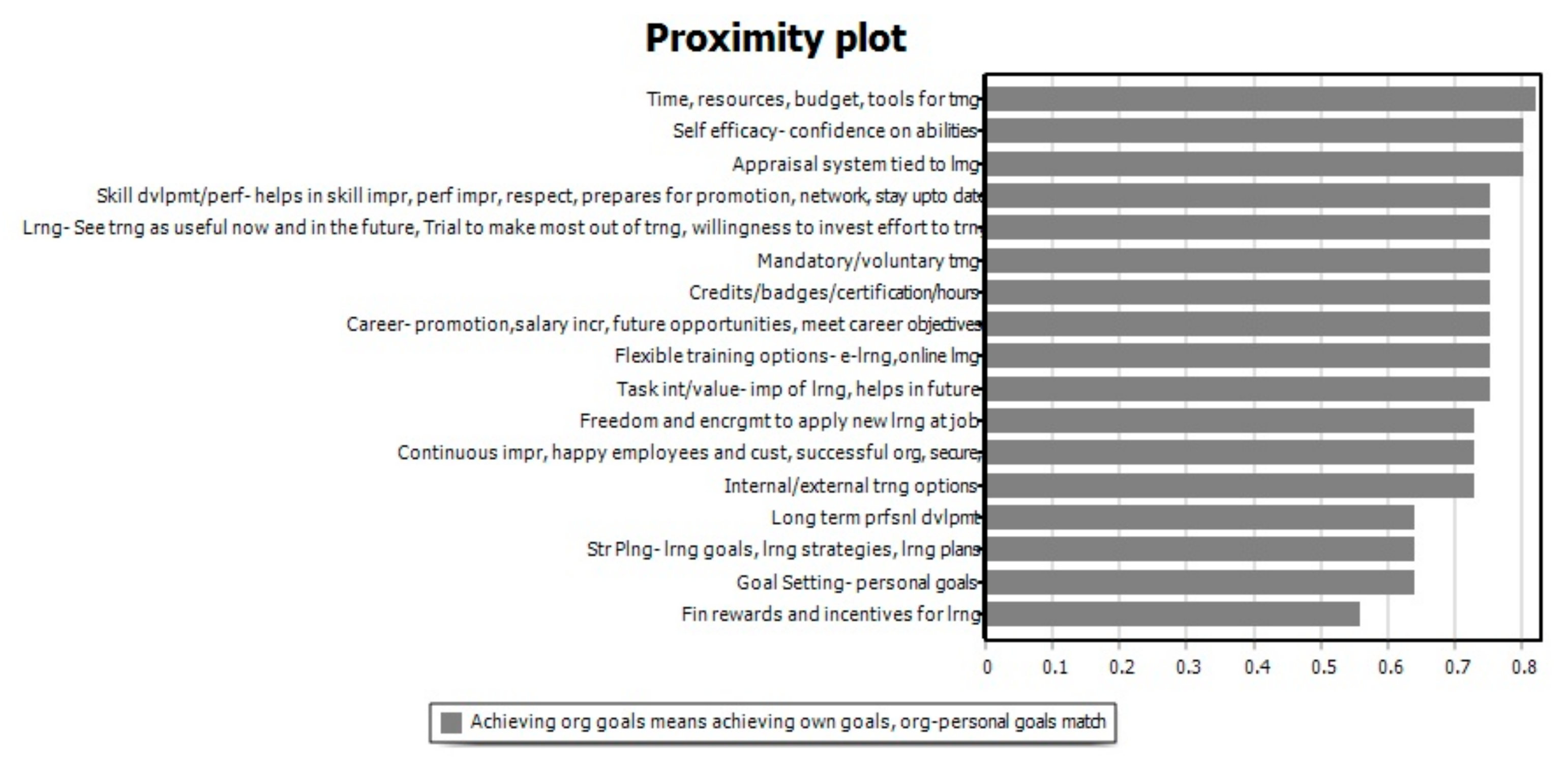

| Championed By | Core Themes | Sub Themes | Interview | Rank | FGD | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | Access to training | The company has a training policy on the amount and type of training that the employees can avail | 53 | 4 | 25 | 2 |

| Goal congruence | Achieving organizational goals means achieving own goals; organizational and personal goals match | 15 | 17 | 30 | 1 | |

| Agent | Individual goal achievement | Skill development/performance goal achievement—Training helps in skill improvement, performance improvement, helps in gaining respect, prepares for promotion, improves network, helps in staying up to date | 72 | 1 | 23 | 3 |

| Learning goal achievement—The long-term perspective of viewing training as useful for the present and the future; intention to make the most out of training, willingness to invest the effort in training | 58 | 2 | 14 | 6 | ||

| Career goal achievement—Training contributes to promotion, salary increase, opens up future opportunities, helps meet career objectives | 25 | 12 | 17 | 5 | ||

| Principal | Organizational goal achievement | Organization shows continuous improvement; employees are happy; customers are happy; organization is successful and has a secure future | 50 | 6 | 23 | 3 |

| Principal | Organizational learning support | Time, resources, budget, tools adopted for training | 53 | 4 | 10 | 9 |

| Flexible training options madeavailable to employees—e-learning, online learning | 42 | 7 | 14 | 6 | ||

| Internal/external training options provided to employees | 28 | 11 | 2 | 19 | ||

| Freedom and encouragement to apply new learning at the job | 24 | 13 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Long term professional development plans for employees | 18 | 15 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Appraisal system tied to learning of employees | 13 | 18 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Financial rewards and incentives for learning | 5 | 19 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Principal | Organizational training assignment | Credits/badges/certification/hours recommended by the organization | 39 | 9 | 6 | 12 |

| Mandatory training and voluntary training options for employees | 30 | 10 | 4 | 18 | ||

| Agent | Self-Regulated Learning | Task interest/value—the importance of learning to the individual, the perceived utility of learning in future | 54 | 3 | 7 | 11 |

| Strategic Planning—Individual’s long-term learning goals, learning strategies and learning plans | 40 | 8 | 12 | 8 | ||

| Goal Setting—personal goals set by the individual | 20 | 14 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Self-efficacy—the individual’sconfidence in their abilities | 17 | 16 | 5 | 17 |

| JUNIOR LEVEL | MID LEVEL | SENIOR LEVEL |

|---|---|---|

| Skill development/performance goal achievement—Training helps in skill improvement, performance improvement, helps in gaining respect, prepares for promotion, improves network, helps in staying up to date | Skill development/performance goal achievement—Training helps in skill improvement, performance improvement, helps in gaining respect, prepares for promotion, improves network, helps in staying up to date | Organization shows continuous improvement; employees are happy; customers are happy; organization is successful and has a secure future |

| The company has a training policy on the amount and type of training that the employees can avail | Credits/badges/certification/hours recommended by the organization | Skill development/performance goal achievement—Training helps in skill improvement, performance improvement, helps in gaining respect, prepares for promotion, improves network, helps in staying up to date |

| Learning goal achievement- The long-term perspective of viewing training as useful for the present and the future; intention to make the most out of training, willingness to invest the effort in training | Learning goal achievement—The long-term perspective of viewing training as useful for the present and the future; intention to make the most out of training, willingness to invest the effort in training | The company has a training policy on the amount and type of training that the employees can avail |

| Task interest/value—the importance of learning to the individual, the perceived utility of learning in future | Task interest/value—the importance of learning to the individual, the perceived utility of learning in future | Time, resources, budget, tools adopted for training |

| Flexible training options made available to employees—e-learning, online learning | Flexible training options made available to employees—e-learning, online learning | Learning goal achievement—The long-term perspective of viewing training as useful for the present and the future; intention to make the most out of training, willingness to invest the effort in training |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madhavan, V.; Venugopalan, M.; Gupta, B.; Sisodia, G.S. Addressing Agency Problem in Employee Training: The Role of Goal Congruence. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043745

Madhavan V, Venugopalan M, Gupta B, Sisodia GS. Addressing Agency Problem in Employee Training: The Role of Goal Congruence. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043745

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadhavan, Vandana, Murale Venugopalan, Bhumika Gupta, and Gyanendra Singh Sisodia. 2023. "Addressing Agency Problem in Employee Training: The Role of Goal Congruence" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043745

APA StyleMadhavan, V., Venugopalan, M., Gupta, B., & Sisodia, G. S. (2023). Addressing Agency Problem in Employee Training: The Role of Goal Congruence. Sustainability, 15(4), 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043745