Abstract

In the present study, we construct a model of greenwashing on employees’ environmental performance based on person–organization fit theory. Path analysis and hierarchical regression methods were used to examine randomly selected data collected from 269 employees in eight Chinese gas service and chemical production companies. The results of the analysis reveal that employees’ perceived person–organization values fit mediates the relationship between organizational greenwashing and employees’ environmental performance; employees’ environmental beliefs not only positively moderate the relationship between corporate greenwashing behavior and employees’ perceived person–organization values fit, but also positively moderate the indirect effect of employees’ perceived person–organization values fit between organizational greenwashing and employees’ environmental performance. We provide some theoretical contributions to organizational greenwashing, and practical implications are also offered.

1. Introduction

The progress of society has led to a greater consideration of sustainability in development, i.e., a greater concern for the balance between social and economic development and natural living conditions [1]. Related discussions are also related to corporate sustainability, where scholars expect to understand the impact of corporate environmental behavior on organizations, such as by exploring self-sustaining green development models, human resource system development models, etc. The goal of the above models is to help companies strike the best possible balance between effectiveness and sustainability [2,3]. However, in practice, companies may not be able to achieve the unity of efficiency and sustainability based on cost considerations, and in response to short-term efficiency pressures companies may generate more environmentally unethical behaviors such as greenwashing [4,5]. Greenwashing refers to the poor performance of an organization that deliberately disguise the facts that the company is polluting the environment to build a good environmental image [6]. Ample empirical evidence shows that greenwashing behavior has a persistent negative impact on organizations and their customers [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In order to better understand how greenwashing can have negative consequences for companies, research on the consequences of greenwashing is gradually increasing. The results show that greenwashing as a corporate unethical behavior can reduce organizational reputation [14], blame attributions [6], and brand reputation [15]. Synchronously, the increase in greenwashing will enhance consumers’ risk perception and reduce customer purchase intentions [7,16], and due to the increase in suspicion about the authenticity of companies’ green products, customers’ green brand trust repair will decrease accordingly [17].

Recently, scholars have begun to focus on the negative effects of greenwashing on members within organizations [18]. It has been noted that employees’ emotions and cognition, as important objects of daily organizational interaction, are also influenced by organizational behaviors [19]. Understanding the impact of greenwashing on members within an organization can help companies take a more holistic view of the potential internal harm [20] and increase their motivation to reduce greenwashing [21]. However, research on the impact of greenwashing on employees within organizations is still inadequate, mainly focusing on employee career satisfaction [20], green environmental behavior [22], and lacking the exploration of mechanisms and constraints on the impact of greenwashing on employees’ performance. Scholars have also shown that corporate ethical climate can influence employees’ perceived person–organization values fit and thus employee attitudes through corporate behavior [23]. Greenwashing behavior, as a behavior that is clearly characterized by negative value orientations, communicates or implies unethical environmental values to the organization [6], and employees who hold higher environmental beliefs in this contextual scenario may create a mismatch with the organization in terms of values.

In present research, more attention has been paid on the role of corporate greenwashing in reducing employees’ environmental performance. According to organizational behaviorists, employees’ environmental performance reflects employees’ work commitment towards the organization’s environmental goals, and high levels of environmental performance are effective at alleviating companies’ concerns about production processes that arise and have received academic attention [24,25,26]. We understand employees’ environmental performance to be those activities related to environmental protection that are defined and required by the firm, described in employee job descriptions, and monitored, authorized, and rewarded by the company [27]. Employee environmental performance is a reflection of employees’ ability to maintain clean production and also implies the ability of employees to identify and solve potential environmental problems at work [27]. More importantly, studies have pointed out that employee environmental performance is an important factor influencing the improvement in organizational environmental performance, and high levels of employee environmental performance can help organizations achieve their environmental goals [25]. Although studies have widely confirmed the contribution of corporate green human resource management, green ambidexterity, and corporate social responsibility to employees’ environmental performance [10,25,28,29], fewer have dealt with how organizational greenwashing negatively affects environmental performance.

According to person–organization (P–O) fit theory, individuals form perceptions of organizational values and behave accordingly by matching them with the organization [30]. High levels of perceived person–organization values fit promote positive work outcomes [14,31], whereas inconsistency in values is associated with negative work outcomes [32,33]. Corporate greenwashing is organizational unethical behavior with egoistic tendencies, and so the implied crisis of values and the inconsistency with the environmental work goals generally pursued by employees should cause a decline in perceived person–organization values fit. It has been noted that perceived person–organizational fit, as a result of individuals’ internalization of organizational values, can further influence subsequent work intentions and job performance [34,35,36]. For this reason, this study introduces perceived person–organization values fit as a mediating variable to uncover the role of corporate greenwashing behavior in influencing employees’ environmental performance “black box”.

Furthermore, according to P–O fit theory, the effect of corporate greenwashing on employees perceived person–organization values fit is not always the same and may also be influenced by certain factors relating to individuals [30], and individuals who uphold environmental beliefs may be more concerned about the negative effects of greenwashing behavior given the false environmental attributes specific to greenwashing [37]. Environmental beliefs are people’s general beliefs about the natural environment [38], and they not only constitute an individual’s perception of the reality of the natural environment of the planet they live on, but also tell individuals how to interact with this reality [39]. Individuals with high environmental beliefs have higher awareness of consequences [40], and are able to uncover more negative effects of unfriendly corporate behavior [41]. They are less tolerant of false environmental behaviors within the organization or in their lives [42], and are more likely to form negative perceptions of the organization [43]. We hypothesized that employees’ environmental beliefs may exacerbate employees’ reduced organizational fit caused by greenwashing. By examining the mediating effect of perceived person–organization values fit and the moderating effect of environmental beliefs, we can further reveal the conditions that influence the relationship between greenwashing and employees’ environmental performance.

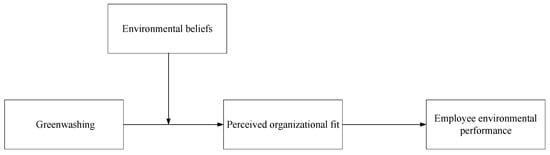

In summary, we attempt to systematically analyze how organizational greenwashing affects environmental performance through perceived person–organization values fit by hypothesizing and validating a mediated model that is moderated, providing three contributions to the study of corporate greenwashing (the theoretical model is shown in Figure 1). First, we advance the understanding of the individual-level consequences of greenwashing behavior by demonstrating that greenwashing behavior decreases employees’ perceived person–organization values fit and leads to a decrease in employees’ environmental performance [18], which is a further exploration of existing studies on the negative effects of greenwashing [20,22]. Second, unlike existing studies, we contribute to the individual environmental performance literature by introducing greenwashing as a negative organizational behavior and by focusing on the negative effects of organizational contextual factors on employees’ environmental performance, responding to the call of the academic community to expand the exploration of factors that influence employees’ environmental performance [25]. Finally, driven by P–O fit theory, we demonstrate that the effect of greenwashing on perceived person–organizational fit and environmental performance is influenced by employees’ environmental beliefs, emphasizing the importance of adopting a fit perspective to understand employees’ environmental commitment and revealing the process by which situational factors and employees jointly determine environmental performance.

Figure 1.

Research model.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Greenwashing and Perceived Person–Organization Values Fit

P–O fit theory is a part of person–environment fit theory [44]. In contrast to person–job fit, person–position fit, and person–person fit, P–O fit emphasizes the compatibility of employees with their organizations and focuses on the influence of the interaction of organizational and personal factors on the subsequent cognition and behavior of individuals [45,46]. This demonstrates that P–O fit is more in line with the findings of the study, and can better reveal the mechanism of the influence of corporate greenwashing on subsequent individual behavior. P–O fit theory states that the match between individuals and organizations involves three main aspects: the fit between individual and organizational values, the fit between individual needs and organizational supply, and the fit between organizational requirements and individual capabilities [33]. P–O fit theory emphasizes corporate behavior as a factor in employees’ perception of organizational climate, which influences their perception of person–organization values fit [47]. The daily behavior of the organization enables the construction of an overall perception of the company, which includes behavior attribution and evaluation of the organization’s implicit values, needs, and capabilities [7,48]. The results of the perceptions serve as a basis for employees to make comparisons of differences in value, further contributing to the formation of employees’ perceived person–organization values fit [49].

Greenwashing is often associated with selective disclosure or decoupling [7,32], and the difference can facilitate negative attributions to the organization by employees [50]. Greenwashing behavior reflects the inconsistency between the organizations’ green development claims and actual corporate activities [9], and highlights the lack of organizational focus on environmental concepts, implying that the organization uses environmental products and services more as a promotional tool, with the real aim of gaining positive responses from stakeholders and higher product sales [51]. Employees within this process need to participate in the formation and external publicity of products or services, so they will form a systematic cognition of the real purpose of corporate greenwashing [20]. Some companies may deliberately conceal the true characteristics of their products or services from employees, but employees can still pick up clues about the social impact of greenwashing from negative social or customer feedback [49]. Greenwashing behavior also reflects the tendency of egoism in organizations, which is contrary to the altruistic values commonly advocated within organizations [50]. Not only does this directly lead to a decrease in employees’ perceived person–organization values fit, but the inconsistency between organizational behavior and values can also lead to uncertain behavioral goals and increasing efforts to communicate with the organization. Furthermore, the unpredictability of organizational behavior reduces employees’ job satisfaction [52] and invites more negative public word-of-mouth [6], which also leads to a decline in employees’ social image and thus contributes to a decline in employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. In summary, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Greenwashing negatively affects employees’ perceived person–organization values fit.

2.2. Perceived Person–Organization Values Fit and Employees’ Environmental Performance

Previous studies have pointed out that perceived person–organization values fit reflects the difference between organizational values and personal values, which is not only affected by organizational factors, but also can significantly influence employees’ cognition and behavioral motivation [23,27,31]. We argue that the decrease in perceived person–organization values fit caused by greenwashing can negatively affect employees’ environmental performance. On the one hand, the decreasing fit caused by greenwashing is related to employees’ environmental values as a psychological process that reduces employees’ identification with the organization’s environmental policy [53]. High levels of fit are often associated with higher job support or positive organizational management [54,55], and the process of perceived person–organization values fit involves differences in expectations of organizational behavior and actual organizational behavior [56]. Smaller differences resonate better with employees [57,58], while larger differences signal deviations in organizational behavior [30], especially if employees perceive their own values or behaviors to be acceptable or socially accepted, and organizational deviant behavior can reduce employee recognition and subsequent work outcomes [56,59]. Considering the context of the present research, for individuals with a low level of perceived person–organization values fit, especially based on the low level of environmental values fit caused by greenwashing behavior, the environmental requirements of the organization will be correspondingly suspected as a false investment by the organization for the environmental performance of the company, which contradicts the true treatment of the environment and society upheld by employees with high environmental beliefs. The implementation of the organization’s environmental requirements will therefore not only be inconsistent with the employees’ environmental behavior expectations, but the public image of the environment that employees expect themselves to have will also be affected [17,32,60], which can further reduce employees’ identification with the organization and lower their expectations of participating in the organization’s environmental behavior [20,22].

On the other hand, low matching also means decline of satisfaction and job acquisition, which further decrease employees’ motivation to work for the environment [58,61]. Hu (2022) stated that the generation of employee behavioral motivation is not only dependent on employee self-efficacy (self-perceived ability to work to be able to accomplish future tasks [62,63]), but is also related to subjective goal value [64]. For jobs with higher attainment value and lower expected costs, employees will have higher estimates of task value and thus higher motivation to work [65]. The low person–organization values fit caused by greenwashing means that employees perceive that their environmental competence is not valued by the organization, and may not receive a corresponding performance evaluation by completing organizational environmental tasks [22,66]. Maintaining a low level of commitment to environmental tasks can also increase the cost for employees to complete environmental tasks (for example, reducing the number of workers to clean up the production site leads to employees having to clean up the production waste themselves). The increase in environmental costs and the decrease in the importance of expected performance reduce the motivation of employees to work within the organization for environmental protection and further lead to the decline of employees’ environmental performance. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

Employees’ perceived person–organization values fit positively influences employees’ environmental performance.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Perceived Person–Organization Values Fit

The existing research already acknowledges the role of person–organization values fit as a mechanism that connects the organizational environment and employee performance [23]. We consider that person–organization values fit mediates the relationship between corporate greenwashing and employee environmental performance. Greenwashing reduces employees’ perception of person–organization values fit, which further reduces employees’ environmental performance. A large number of studies have shown that greenwashing inhibits organizational development because it adversely affects managerial decision making and employee behavior [22,67]. Greenwashing communicates lower environmental requirements to employees, and reduces the environmental integrity of the organization [37]. This organizational climate that deviates from social norms increases employees’ value deviation and reduces their willingness to work [22], especially as the production of environmental compliance behavior will be interpreted as active participation in the organization’s greenwashing, and this perception will further reduce employees’ environmental outcomes in the workplace. On the other hand, greenwashing is commonly treated as short-sighted behavior by the organization [7], which is inconsistent with employees’ individual development plans and further exacerbates the perceived mismatch, and employees are more inclined to level the gap between their work status and expectations by reducing their work inputs (e.g., lowering organizational environmental performance). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3:

The negative relationship between greenwashing and employees’ environmental performance is mediated by employees’ perceived person–organization values fit.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Employee Environmental Beliefs

According to P–O fit theory, employees’ judgment of organizational fit is also influenced by personal attitude [30]. In particular, attitudes associated with organizational behavior promote employees to pay more attention to the extent to which organizational behavior matches their expectation [46]. Corresponding to greenwashing, we argue that employees’ environmental beliefs, as personal environmental attitudes, are considered to amplify the impact of corporate greenwashing on employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. Environmental beliefs describe a set of behavioral standards and convictions that individuals uphold to promote good environmental development [37], which can facilitate individuals to pay more attention to the impact of their personal and organizational behavior on the environment [40], and may form more value-negative perceptions of greenwashing behavior in organizational business activities. With high environmental beliefs, employees not only need to be able to act on their own to protect the environment, but also want to contribute to positive social perceptions of the environment through their efforts [68], and they develop more positive feelings and organizational identity when their positive attitude toward the environment is recognized as useful to the organization [69]. However, greenwashing highlights that the actual needs of companies are not for corporate green practices or greener products [8]. Under the fog of green propaganda, employees perceive that companies are only pursuing short-term financial gains, and this divergence between needs and capabilities exacerbates perceptions of inconsistency.

Correspondingly, employees with low levels of environmental beliefs do not pay much attention to the consequences caused by environment-related behaviors in the organization and are unable to deeply comprehend the long-term impact that greenwashing has on the organization and individuals [22]. Environmental factors have less influence on the process of judging the fit between employees and organizational values, and employees are unable to internalize society’s pursuit of the environment as a personal concern for green jobs [70]. At the same time, the short-term impact of greenwashing on employees is often indirectly reflected through society such as through corporate reputation and brand image [16,71,72], which does not have an impact on employees’ personal work and performance in the short term. Employees are unable to make timely moral evaluations of organizational greening behavior, which further reduces the degree of organizational mismatch based on values considered by employees. Based on the above, the hypothesis is summarized as:

Hypothesis 4:

Environmental beliefs moderate the relationship between greenwashing and employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. Particularly, environmental beliefs will strengthen the negative relation between greenwashing and employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. The negative association will be stronger when environmental beliefs are high and will be weaker when environmental beliefs are low.

Integrating Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, we further construct an overall model with moderated mediation in the first stage. Specifically, when employees’ environmental beliefs are high, the lack of attention to environmental goals by the organization embodied by greenwashing behavior promotes a decrease in perceived person–organization values fit, which in turn negatively affects employees’ environmental performance. Greenwashing may not directly affect employees’ environmental performance, but it has been shown that greenwashing leads to persistent social and moral risks [32], and it may cost more to avoid business problems caused by negative social comments and a lower social image [67]. The negative results caused by corporate greenwashing are expected to reduce employees’ work attractiveness and organizational identity, especially in the context of high levels of environmental beliefs. The gap between organizational behavior and environmental beliefs is thus further widened, resulting in an increased negative impact on perceived person–organization values fit. Employees may maintain job acquisition by cutting back on work inputs or lowering job performance, especially environmental performance, within the organization [20].

It is assumed that ’hen employees’ environmental beliefs are low, the relationship between greenwashing through employees’ perceptions of person–organization values fit affecting environmental performance is weakened. It has been noted that low levels of employees’ environmental beliefs tend to negatively affect environmental support [40], awareness of consequence [42], and organizational citizenship behavior towards the environment [70]. Environmental beliefs, as an individual’s overall perception of natural vulnerability, can promote employees to develop more awareness of environmental crises and pay more attention to the negative environmental hazards of human activities [43]. Employees are then more motivated to identify and react to factors in their activities that are harmful to nature [40]. Conversely, employees who are devoid of environmental beliefs are insensitive to environmental cues around them [68], unable to fully realize the environmental threat of greenwashing behavior [70], and incapable of internalizing the social and moral crisis caused by greenwashing behavior as a contradiction to the beliefs they uphold [24]. Lower levels of environmental beliefs are likely to focus more on other aspects of the employee’s life and prevent them from developing negative perceptions of the organization’s values, which in turn will have a lower negative impact on perceived person–organization values fit. Further, decreased enthusiasm for environmental behavior will increase the negative impact on employees’ environmental performance. Employees who are devoid of environmental beliefs are insensitive to environmental cues around them [42,72], unable to fully realize the environmental threat of greenwashing behavior, and incapable of internalizing the social and moral crisis caused by greenwashing behavior as a contradiction to the beliefs they uphold. Lower levels of environmental beliefs are likely to focus more on other aspects of the employee’s job and prevent them from developing negative perceptions of the organization’s values, which in turn will have a lower negative impact on perceived organizational fit. Further, the negative impact on employees’ environmental performance will be simultaneously diminished. Taking the above together, we propose Hypothesis 5:

Hypothesis 5:

Environmental beliefs moderate the indirect negative effect of greenwashing on employees’ environmental performance through perceived person–organization values fit. Particularly, environmental beliefs will strengthen the indirect negative relation between greenwashing and employees’ environmental performance through employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. The negative association will be stronger when environmental beliefs are high and will be weaker when environmental beliefs are low.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

Questionnaires were used to collect dyad data on employees and leaders, covering a total of 8 gas service and chemical production companies in 3 cities. Researchers obtained the list of employees and their immediate superiors from the human resources departments of the investigated organizations. Researchers contacted the company’s human resources department and asked HR to randomly select 50 people from a list of front-line employees, most of whom were from the production department and were familiar with the workflow of the product or service. Then, a confidentiality statement and questionnaire were distributed through the company’s internal office system. The confidentiality statement guaranteed the confidentiality and use of the data. To reduce the impact of common method bias on the study results, following the recommendations of Paillé (2019) and Podsakoff (2003), this study conducted data collection at three-time points, each with an interval of three months [26,73]. At Time 1, we collected basic information about employees’ perceived corporate greenwashing and environmental beliefs. At Time 2, we focused on collecting employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. Time 3 point data collection objects were the leaders of employees who received feedback information from the previous two questionnaires. Questionnaires involved superiors’ evaluation of their subordinates’ environmental performance. Researchers, through on-site coaching and online responses, focused on the process of filling out questionnaires; the entire process of filling out questionnaires followed the principle of voluntary employees and leaders to ensure the authenticity and reliability of the data. At Time 1, a total of 400 questionnaires were distributed, and 347 valid questionnaires were collected after eliminating inappropriate questionnaires. At Time 2, questionnaires was administered to employees who had completed the questionnaire in Time 1, and 289 valid questionnaires were collected. At Time 3, some questionnaires were not filled out effectively due to leaders leaving or being on business trips, and finally 263 valid questionnaires were returned with an overall response rate of 65.75%. Among the final valid questionnaires, 150 respondents (57.00%) were male. Of the employees, 102 were between the ages of 19 and 30, 118 were between 31 and 40, and the rest were 40 years old. The average organizational tenure of the participants was 3.26 years (SD = 2.42), and the educational level of the participants was distributed as follows: associate college (41.1%), 4-year university (49.8%), and graduate school (9.1%). The demographic information for both leaders and employees is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information.

3.2. Measures

Given that the context of this study was China, all the assessments needed to be conducted through Chinese. In order to ensure the validity of the questionnaire items, we followed the translation–back translation procedure and invited two relevant experts and four PhD students to conduct an independent assessment of the questionnaire quality. The invited participants processed the content of the question items using two-way translation, then compared the different translation results, held a group discussion on the translation of the ambiguous question items, and then selected the agreed result as the accurate translation of the ambiguous question items. In addition to the control variables, five-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) were used.

A 3-item scale developed by Ong and Mayer (2018) was used for corporate greenwashing [74]. The scale is widely used in relevant research, with typical items such as “My organization has poor social and environmental performance but sells itself as socially responsible”. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.804.

A 6-item NEP scale developed by Gooch (1995), with some modifications, was used to measure employees’ environmental beliefs and contains 6 standard scoring items [75]. Sample items include “The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset by human activities”. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.797.

Perceived person–organization values fit was measured using Cable’s (1996) person–organization fit scale, which consists of three items [76], a sample item is “The things that I value in life are very similar to the things that my organization values”. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.851.

Employees’ environmental performance was measured using a scale developed by Janssen (2004), which consists of three items [77]. For the contextual background and purpose of this study, we adapted it to better fit the research topic. A sample item is “He/She completes the environmental duties specified in the job”. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.934.

Previous studies have demonstrated that demographic variables such as gender and age have an impact on employees’ environmental performance [78,79], so we controlled for gender, age, and education level. We further controlled for employees’ job tenure because employees need to participate in a certain number of company tasks to perceive the generation of greenwashing.

3.3. Method of Analysis

The statistical tools SPSS21.0 and Mplus8.3 were used to analyze the data. We used SPSS21.0 for descriptive statistical analysis of samples, factor analysis, reliability tests, inter-factor correlation analysis, and model direct and indirect effects analysis (using the hierarchical regression analysis provided by SPSS) involving Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2, Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 4. Mplus8.3 was used for confirmatory factor analysis and Hypothesis 5 (using MOME analysis provided by Mplus). Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the high and low standard deviation groups reporting indirect effects using bootstrapping to estimate 95% confidence intervals and determine the significance [80].

We used Cronbach’s alpha coefficients to assess the reliability of the scales. The Cronbach’s alpha for all constructs was between 0.797 and 0.934, which exceeds the recommended minimum standard value (above 0.7). Moreover, according to Table 2, the composite reliability (CR) of variables was more than 0.7, from 0.846 to 0.896. Therefore, the reliability of the measurements is acceptable.

Table 2.

Convergent Validity.

We measured the validity of the constructs in several ways, as well as the use of established scales and the use of a standardized translation-back translation procedure to ensure the content validity of the scales. To test discriminant validity, we calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) for each variable. Despite the low AVE values of some variables, their CR values were greater than 0.7, so their discriminant validity was still acceptable [81]. The results of the square root of AVEs ranged between 0.693 and 0.861, and the correlation coefficients between the constructs ranged between 0.007 and 0.539. The square root of the variables’ AVEs was greater than the correlation coefficients between the variables and other variables, thus confirming the discriminant validity, as shown in Table 3. The results of the loading factors for each variable showed that each item loaded onto the corresponding structure with a factor loading range between 0.630 and 0.887. Although the loading factors for most of the items were in the acceptable range (above 0.49), there were still some question items with low loading. We used the scales with complete question items in the subsequent analyses because they are the original measures of the scale and have undergone a complete and scientific psychometric process. Additionally, the results of the reliability analysis of the items showed that the present structure was adequate for the follow-up study [82] and was consistent with the results of other studies [83].

Table 3.

Correlation and the square roots of AVEs.

In the current study, we used Mplus 8.3 to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on greenwashing, employees’ environmental beliefs, perceived person–organization values fit, and employees’ environmental performance. Judging from the indicator values of RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in Table 4, the model in this study has a better fit compared to the other three alternative models, and the results of the analysis show that the scales have better construct validity.

Table 4.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis (N = 263).

Due to greenwashing, environmental beliefs, and perceived person–organization values fit in our study being all self-reported by participants, there may be a possibility of common method bias. Thus, in addition to reducing the effect of bias by collecting paired data across three-time points, we also applied Harman’s one-factor method according to the suggestion of Cooper [84]. Results showed that the variance explained by the first-factor rate was 34.559%, which was less than the critical value of 40%, indicating that the common method bias is within the normal range.

4. Statistical Analysis and Results

Table 5 shows the correlation coefficients, means, and standard deviations of the main study variables. Corporate greenwashing was only significantly negatively correlated with employees’ perceived person–organization values fit (b = −0.155, p < 0.05). Conversely, employees’ environmental performance was significantly positively correlated with employees’ perceived person–organization values fit (b = 0.539, p < 0.01). The results of the correlation analysis were consistent with the theoretical hypotheses and provided the basis for the subsequent analysis.

Table 5.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for variables (N = 263).

This study used hierarchical regression analysis to test hypotheses, and the results of the regression analysis are shown in Table 6. Hypothesis 1 suggests that greenwashing negatively affects employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. According to model 1 and model 2 in Table 6, it can be seen that greenwashing negatively affects employees’ perceived person–organization values fit (b = −0.147, p< 0.01). Hypothesis 1 is supported. Hypothesis 2 predicts that perceived person–organization values fit positively affects employees’ environmental performance. As shown in model 5, perceived person–organization values fit is significantly and positively related to environmental performance (b = 0.481, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 2 is supported. In addition, we tested the direct relationship between greenwashing and employees’ environmental performance, although we did not formulate a relevant hypothesis. Model 6 of Table 6 shows that the direct relationship between greenwashing and employees’ environmental performance is not significant (b = −0.024, p = 0.523).

Table 6.

Analysis of mediating and moderating effects (N = 263).

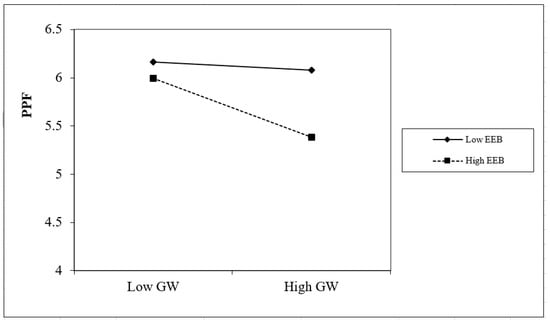

Hypothesis 4 proposes that employees’ environmental beliefs play a moderating role in greenwashing and employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. From model 3 in Table 6, the interaction between greenwashing and environmental beliefs is significantly negatively related to perceived person–organization values fit (b = −0.212, p < 0.01). To more visually demonstrate the moderating effect of employees’ environmental beliefs, we classified different levels of environmental beliefs and moderated the effect by using the mean plus or minus one standard deviation mapping. As shown in Figure 2, the results of the simple slope test indicate that for employees with high environmental beliefs, there is a negative effect of corporate greenwashing on perceived person–organization values fit. Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Figure 2.

The interaction between corporate greenwashing and employees’ environmental beliefs on employees’ perceived person–organization values fit.

Further, in order to test Hypothesis 3, we adopted the suggestion of Hayes (2017) and Lv (2023) to test the mediation effect using bootstrapping method, and the test results are shown in Table 7. It is clear that person–organization values fit has a significant mediating effect on the impact of greenwashing on employees’ environmental performance. The indirect effect is −0.0594 and the 95% confidence interval is [−0.1186, −0.009], and Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Table 7.

Results of mediating effect.

Hypothesis 5 predicts that employees’ environmental beliefs amplify the indirect effect of corporate greenwashing affecting employees’ environmental performance through employees’ perceived person–organization values fit. To test this moderated mediating effect, we used Mplus8.3 to obtain interval values for the difference between the moderated mediating effects through Bootstrap 5000 sampling. Results are presented in Table 8. It shows that the mediating effect of the model under high employees’ environmental beliefs is able to reach a statistically significant level (b = −0.140, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.204, −0.087], excluding 0), while the mediating effect of perceived person–organization values fit under low levels of environmental beliefs is unable to reach a statistically significant level (b = −0.020, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.088, 0.038], including 0). We provide a preliminary discussion of this interesting result in the discussion section. The verification results of Hypothesis 4 show that the indirect effect of corporate greenwashing on employees’ environmental performance through perceived person–organization values fit is more significant when employees’ environmental beliefs are at a high level, and there are significant differences in indirect effects of the model at different levels of environmental beliefs (DIFF = −0.120, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.203, −0.045]. Hypothesis 5 is valid.

Table 8.

Results of moderated mediation effect.

5. Discussion

Recently, the drive of sustainability for corporate development has received continuous attention from the academic community. Studies have revealed the negative impact of greenwashing on corporate sustainability [1,2,3], while the negative impact of greenwashing on employees’ work output is also a topic for discussion, as employees’ work performance is an important indicator of corporate sustainability [22].

The findings of Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2, and Hypothesis 3 respond to the call of scholars to expand research on the negative effects of greenwashing on employees [20]. The analysis revealed that greenwashing negatively affects employees’ environmental performance, and complements extant research in which greenwashing behavior predicts negative employee outcomes such as career satisfaction, organizational pride, affective commitment, and green behavior [20,22]. Further, this study shows that greenwashing does not directly affect employees’ environmental performance. The effect of greenwashing on environmental performance needs to be mediated through perceived person–organization values fit, suggesting that the effect of organizational behavior represented by greenwashing on employees’ environmental performance is confounded by personal and contextual factors. This is consistent with the existing studies on environmental performance [25,26,27], emphasizing the role of employee perception in organizational behavior affecting employee environmental performance. The findings of Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 4 show that employees’ environmental beliefs reinforce the negative effect of corporate greenwashing on perceived person–organization values fit and environmental performance. Interestingly, only high environmental beliefs reinforces the indirect effect of corporate greenwashing on environmental performance through perceived person–organization values fit. One possible explanation for this result is that, with low environmental performance, employees do not focus on the positive effects of their personal behavior on the environment compared to employees with high environmental performance. Employees with low environmental beliefs tend to ignore the negative effects of enterprises’ non-environmental behaviors, and do not add to their own moral burden as a result of corporate greenwashing. Therefore, it may result in less change in their perception of P–O fit.

In the section below, the theoretical and practical implications of these findings will be discussed, and some limitations and opportunities for future research will be noted.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, we reveal the negative impact of corporate greenwashing on employees’ environmental performance, extending the research on the impact of corporate greenwashing on the micro-level within firms. Given the diverse and long-lasting consequences of greenwashing on society [6,32,37], it is logical to anticipate that corporate greenwashing can elicit unfavorable responses from personnel. We provide evidence for the negative impact of corporate greenwashing on employees’ organizational performance through an empirical analysis within the framework of P–O fit theory. Specifically, we present a theoretical model that explains why corporate greenwashing negatively affects employees’ environmental performance. The result not only responds to the call to extend research on the negative impact of greenwashing but also extends research on the factors affecting employees’ environmental performance.

Second, we improved the research on the influence of greenwashing on employees’ environmental performance by proving the mediator effect of perceived person–organization values fit, an employee cognitive factor, in the influence of corporate greenwashing on environmental performance. This is an innovative attempt in the research on the influence mechanism of corporate greenwashing, and reveals the negative impact of corporate greenwashing on employee cognition and expands the exploration of organizational behaviors that influence employees’ environmental performance [10,25,78].

In addition, we have provided a new theoretical framework for the study of corporate greenwashing and P–O fit theory [35,53,56]. The citation of this theory not only explains the process by which corporate greenwashing influences perceived person–organization values fit and clarifies the mechanism of greenwashing affecting employees’ environmental performance, but also identifies the moderating role of employees’ environmental beliefs in this impact process, which provides a theoretical basis for subsequent corporate greenwashing. We highlight the impact of environmental beliefs on workers’ job perceptions and behaviors by addressing this topic and providing a theoretical foundation for future research on employees’ environmental cognition.

5.2. Practical Implications

For organizations that need to increase their environmental competitiveness by means of improving the environmental performance of their employees, our study offers two practical implications of relevance. First, organizations should minimize greenwashing behavior, which this paper shows can lead to a mismatch between employee and organizational values. Organizations can reduce greenwashing by adopting the science of information disclosure and strong environmental information transfer within the organization. On the one hand, a third-party team containing industry experts and user representatives can be hired to audit the information disclosed by the organization and reduce public skepticism about the disclosed information. On the other hand, companies can ensure the transmission of true environmental information through efficient internal communication, such as by using departmental meetings, internal discussions, or leadership–subordinate two-way communication to collect employees’ views on inconsistent environmental information in service implementation or product sales, and respond to them in a timely manner to improve employees’ work motivation and environmental identity.

Second, considering the important role of environmental beliefs in employees’ perception of person–organization values fit, organizations should enhance employees’ environmental beliefs and positive feedback on organizational environmental behavior through continuous investment. Organizations can strengthen employees’ environmental awareness by creating a positive environmental climate. Regular environmental training and community environmental activities should be conducted to enhance employees’ environmental knowledge and concerns, replace safer and environmentally friendly production equipment to reduce environmental hazards and increase environmental safety in the workplace, and post environmental advocacy and examples of environmental protection within the organization in the workplace to enhance employees’ sense of agency. Simultaneously, organizations should encourage employees to take the initiative to implement environmentally friendly behaviors. They should incorporate employees’ environmental opinions and the role they play in departmental planning decisions into incentives as a measurement factor in employee promotions or performance evaluations.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

The main research limitations of the current study are as follows: First, although factors that influence employees’ environmental performance include both in-role and extra-role environmental behaviors [85], this study only focuses on the environmental performance dominated by in-role environmental behavior. In fact, we believe that, compared to in-role environmental behavior, extra-role environmental behavior is also influenced by person–organizational value fit and greenwashing. Follow-up studies should more comprehensively consider the differences in the effects of organizational behavior on employees’ in-role environmental behavior and extra-role environmental behavior to extend the depth of related research.

Secondly, although we collected data across several time points, it was not possible to determine the causal relationships between the variables, and future research could deepen the study through experiments or more rigorous longitudinal research methods.

Thirdly, individual environmental beliefs may vary greatly across countries or cultural values, and the perception of corporate greenwashing behavior varies across cultures and societies. Finally, individual environmental beliefs may differ greatly in different countries or different cultural values, and there are also differences in the cognition of enterprises’ greenwashing behavior in different cultures and societies. The samples of this study were mainly from Chinese enterprises, which limited the universality of the research results. Future studies can improve the universality of research conclusions by collecting data from different countries and cultural backgrounds. Additionally, both traditional and emerging industries currently emphasize development sustainability [86,87], and the manifestation of greenwashing behavior may vary among industries. A study of them may further reveal differences in the impact of greenwashing.

Finally, subsequent studies may try to reveal the promotion of greenwashing behavior on employees’ positive behaviors while greenwashing can have a negative impact on employees. Based on trait activation theory, the activation of employee traits requires certain organizational climate cues, and considering the unethical nature of greenwashing, research on its stimulation of employee traits may reveal the positive effects of greenwashing.

6. Conclusions

Based on P–O fit theory, we explored the relationship between greenwashing and employees’ environmental performance. Data for the study were obtained from employees at three times involving eight gas service and chemical production companies in three cities. The findings suggest that greenwashing negatively affects employees’ environmental performance through perceived person–organization values fit. In addition, employees’ environmental beliefs moderate the indirect relationship between greenwashing and environmental performance through perceived person–organization values fit. Previous studies have focused more on the negative effects of greenwashing behavior on organizations’ and customers’ contextual background. However, scholars have suggested that the negative impact of greenwashing exists not only outside the organization but also inside the organization, and the present study has explored the influence of greenwashing on roles inside the organization based on employee perspectives. This study also discusses the implications for expanding negative research on greenwashing, highlighting the importance of and ways to focus on employees’ environmental beliefs and enhance employee value matching in practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.W. and G.M.; methodology, G.M.; software, G.M.; validation, F.W., G.M. and G.C.; formal analysis, G.M.; investigation, F.W.; resources, G.C.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.; writing—review and editing, F.W.; visualization, F.W.; supervision, A.K.D.; project administration, F.W.; funding acquisition, A.K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the correspondence author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ehnert, I. Sustainability and human resource management: Reasoning and applications on corporate websites. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 3, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green human resource management: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Harry, W. Recent developments and future prospects on sustainable human resource management: Introduction to the special issue. Manag. Rev. 2012, 23, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.; Ramey, W. Look how green I am! An individual-level explanation for greenwashing. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2011, 12, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzetti, M.; Gatti, L.; Seele, P. Firms Talk, suppliers walk: Analyzing the locus of greenwashing in the blame game and introducing ‘vicarious greenwashing’. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 170, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Bernard, S.; Rahman, I. Greenwashing in hotels: A structural model of trust and behavioral intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimonenko, T.; Bilan, Y.; Horák, J.; Starchenko, L.; Gajda, W. Green brand of companies and greenwashing under sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, Z. The Influence of Green Marketing on Brand Trust: The Mediation Role of Brand Image and the Moderation Effect of Greenwash. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 6392172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Hyder, Z.; Imran, M.; Shafiq, K. Greenwash and green purchase behavior: An environmentally sustainable perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13113–13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesenheimer, J.S.; Greitemeyer, T. Greenwash yourself: The relationship between communal and agentic narcissism and pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 75, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabieh, S. The impact of greenwash practices over green purchase intention: The mediating effects of green confusion, Green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ji, X.; Cai, L. Greenwash, moral decoupling, and brand loyalty. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cooman, R.; Mol, S.T.; Billsberry, J.; Boon, C.; Den Hartog, D.N. Epilogue: Frontiers in person–environment fit research. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cordero, E.; Cabrera-Sánchez, J.P.; Cepeda-Carrión, I.; Ortega-Gutierrez, J. Measuring Behavioural Intention through the Use of Greenwashing: A Study of the Mediating Effects and Variables Involved. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, C.; Huang, S. The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: The mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Li, C.B.; Tao, L. Timely or considered? Brand trust repair strategies and mechanism after greenwashing in China—From a legitimacy perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 72, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, C.; Foerstl, K.; Schleper, M.C. Antecedents of green supplier championing and greenwashing: An empirical study on leadership and ethical incentives. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 152, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q. Socially responsible human resource management and hotel employee organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A social cognitive perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Coelho, A.; Marques, A. Does Greenwashing Affect Employee’s Career Satisfaction? The Mediating Role of Organizational Pride, Negative Emotions and Affective Commitment. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.B.L.; Sirsly, C.A.T. Determinants and consequences of employee attributions of corporate social responsibility as substantive or symbolic. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, R.; Athar, M.R.; Afzal, A. The impact of greenwashing practices on green employee behaviour: Mediating role of employee value orientation and green psychological climate. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1781996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Martínez-Cañas, R.; Fontrodona, J. Ethical culture and employee outcomes: The mediating role of per-son-organization fit. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, S. The nature of environmental activism among young people in Britain in the twenty-first century. Political Ecol. Environ. Br. 2020, 89–109. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03279388/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Naz, S.; Jamshed, S.; Nisar, Q.A.; Nasir, N. Green HRM, psychological green climate and pro-environmental behaviors: An efficacious drive towards environmental performance in China. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Meija-Morelos, J.H. Organisational support is not always enough to encourage employee environmental performance. Moderating Role Exch. Ideol. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Shahbaz, M.; Huynh, T.L.D.; Usman, M. Managing environmental challenges: Training as a solution to improve employee green performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 269, 110781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.Z.; waqas Kamran, H.; Scholz, M.; Han, H. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: The mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Úbeda-García, M.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P.C.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E.; Poveda-Pareja, E. Green ambidexterity and environmental performance: The role of green human resources. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L. Perceived applicant fit: Distinguishing between recruiters’ perceptions of person-job and person-organization fit. Pers. Psychol. 2000, 53, 643–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; Youngs, P. Person-organization fit and first-year teacher retention in the United States. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 97, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.D.L. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.H.; Huang, M.L. Hospitality employees’ spirituality and deviance in the workplace: Person–organization fit as a mediator. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2022, 50, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Woehr, D.J. A quantitative review of the relationship between person–organization fit and behavioral outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.W.; Pan, S.Y. A multilevel investigation of missing links between transformational leadership and task performance: The mediating roles of perceived person-job fit and person-organization fit. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, K.; Kumar, A. Employer brand, person-organisation fit and employer of choice: Investigating the moderating effect of social media. Personnel Review 2019, 48, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, S.; Webster, J. Perceived greenwashing: The effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. The effects of environmental and luxury beliefs on intention to patronize green hotels: The moderating effect of destination image. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 904–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, K.; Saad, C.S.; Kim, H.S. Religiosity moderates the link between environmental beliefs and pro-environmental support: The role of belief in a controlling god. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 47, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, M.; Delevoye-Turrell, Y.N. The cognitive load of physical activity in individuals with high and low tolerance to effort: An ecological paradigm to contrast stepping on the spot and stepping through space. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 58, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young travelers’ intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Collado, S.; Profice, C.C. Measuring Brazilians’ environmental attitudes: A systematic review and empirical analysis of the NEP scale. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.J.; Kristof-Brown, A. Toward a multidimensional theory of person-environment fit. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chu, F.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y. Authentic leadership, person-organization fit and collectivistic orientation: A moderated-mediated model of workplace safety. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Williams, K.A.; Ramayah, T.; Aldieri, L.; Vinci, C.P. Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: The moderating role of person–organization fit. Pers. Rev. 2020, 50, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano Archimi, C.; Reynaud, E.; Yasin, H.M.; Bhatti, Z.A. How perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee cyni-cism: The mediating role of organizational trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, N. Research on the impact of career management fit on career success. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 59, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topal, İ.; Nart, S.; Akar, C.; Erkollar, A. The effect of greenwashing on online consumer engagement: A comparative study in France, Germany, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.; Pizzetti, M.; Seele, P. Green lies and their effect on intention to invest. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 127, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, S.; Dutta, T.; Ghosh, P. Linking employee loyalty with job satisfaction using PLS–SEM modelling. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1695–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.; Elsetouhi, A.; Negm, A.; Abdou, H. Perceived person-organization fit and turnover intention in medical centers: The mediating roles of person-group fit and person-job fit perceptions. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 863–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J.K.; Bawole, J.N. Testing the mediation effect of person-organisation fit on the relationship between talent management and talented employees’ attitudes. Int. J. Manpow. 2018, 39, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saether, E.A. Motivational antecedents to high-tech R&D employees’ innovative work behavior: Self-determined moti-vation, person-organization fit, organization support of creativity, and pay justice. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2019, 30, 100350. [Google Scholar]

- Sørlie, H.O.; Hetland, J.; Bakker, A.B.; Espevik, R.; Olsen, O.K. Daily autonomy and job performance: Does person-organization fit act as a key resource? J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 133, 103691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, K.Y.; Hsu, H.H.; Thomas, C.L.; Cheng, Y.C.; Lin, M.T.; Li, H.F. Motivating employees to speak up: Linking job autonomy, PO fit, and employee voice behaviors through work engagement. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 41, 7762–7776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.S.; Mansor, N.N.A.; Saufi, R.A. Does organizational reputation matter in Pakistan’s higher education institutions? The mediating role of person-organization fit and person-vocation fit between organizational reputation and turnover intention. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2021, 18, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.; Xin, C.; Peng, X.; Siyal, A.W.; Ahmed, W. Why do high-performance human resource practices matter for employee outcomes in public sector universities? The mediating role of person–organization fit mechanism. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020947424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Huynh, T.L.D.; Santos, C. Greening hotels: Does motivating hotel employees promote in-role green performance? The role of culture. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. Available online: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/31750/ (accessed on 22 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Greguras, G.J.; Diefendorff, J.M. Different fits satisfy different needs: Linking person-environment fit to employee com-mitment and performance using self-determination theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Jimmieson, N.L.; White, K.M. Understanding compliance with safe work practices: The role of ‘can-do’and ‘reason-to’factors. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2022, 95, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Marsh, H.W.; Parker, P.D.; Morin, A.J.; Dicke, T. Extending expectancy-value theory predictions of achievement and aspirations in science: Dimensional comparison processes and expectancy-by-value interactions. Learn. Instr. 2017, 49, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, F.; Tsai, Y.M.; Eccles, J.S. Math-related career aspirations and choices within Eccles et al.’s expectancy–value theory of achievement-related behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R.; Balluchi, F.; Lazzini, A. Greenwashing and environmental communication: Effects on stakeholders’ percep-tions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrón-Vílchez, V.; Valero-Gil, J.; Suárez-Perales, I. How does greenwashing influence managers’ decision-making? An experimental approach under stakeholder view. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 860–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, C.N.T. Impact of environmental belief and nature-based destination image on ecotourism attitude. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz, U.; Ali, Y.; Petrillo, A.; De Felice, F. Identifying the critical factors of green supply chain management: Environmental benefits in Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; McGinley, S.; Choi, H.M.; Agmapisarn, C. Hotels’ environmental leadership and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.D.T.; Huluba, G.; Beldad, A.D. Different shades of greenwashing: Consumers’ reactions to environmental lies, half-lies, and organizations taking credit for following legal obligations. J. Bus. Technol. Commun. 2020, 34, 38–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D.; Matthes, J.; Naderer, B. Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect–reason–involvement ac-count of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, M.; Mayer, D.M.; Tost, L.P.; Wellman, N. When corporate social responsibility motivates employee citizenship behavior: The sensitizing role of task significance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2018, 144, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooch, G.D. Environmental beliefs and attitudes in Sweden and the Baltic states. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Judge, T.A. Person—organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O.; Van Yperen, N.W. Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Ashraf, Z.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, R.G.; Channa, N.A. Promoting environmental performance through green human resource management practices in higher education institutions: A moderated mediation model. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Chen, J.; Del Giudice, M.; El-Kassar, A.N. Environmental ethics, environmental performance, and competitive advantage: Role of environmental training. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Mono-Graphs 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.W. Impact of competitiveness on salespeople’s commitment and performance. J. Bus. Res Lam Earch 2012, 65, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar, E.F.; Lew, D.K.; Wallmo, K. The importance of survey content: Testing for the context dependency of the New Ecological Paradigm Scale. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 51, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, B.; Eva, N.; Fazlelahi, F.Z.; Newman, A.; Lee, A.; Obschonka, M. Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 121, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Killmer, A.B.C. Corporate greening through prosocial extrarole behaviours–a conceptual framework for employee motivation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Neto, G.C.; da Silva, P.C.; Tucci, H.N.P.; Amorim, M. Reuse of water and materials as a cleaner production practice in the textile industry contributing to blue economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 305, 127075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.G.; da Silva, V.H.C.; Pinto, L.F.R.; Centoamore, P.; Digiesi, S.; Facchini, F.; Neto, G.C.D.O. Economic, environmental and social gains of the implementation of artificial intelligence at dam operations toward Industry 4.0 principles. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).