When there is a large amount of information in the external environment but limited cognitive resources for entrepreneurs, their environmental scanning activities show the following characteristics [

31]: entrepreneurs will selectively scan environmental information in different fields; alternatively, entrepreneurs will appropriately allocate cognitive resources to environmental scanning activities, which is reflected in the entrepreneurs’ effort and sustainability level compared with other work when they carry out environmental scanning activities. Both of these characteristics will be analyzed in the following paragraphs.

2.3.1. The Mediating Effect of Environmental Scanning Field

The dominant business model with institutional attributes is the authority in the entrepreneurs’ minds, which means that the dominant model is representative of the correct model [

8], making environmental scanning activities containing cognitive biases based on this appropriate. If there are more various general schemas, the entrepreneur will pay more attention to the familiar information related to the dominant model when designing the business model and think less about whether the information is valuable. Unfamiliar information means high uncertainty [

28]. Entrepreneurs cannot judge whether it is a threat or an opportunity according to the existing cognitive schema. Therefore, they tend to ignore unfamiliar information that is difficult to effectively control. In addition, the institutional attributes of the dominant business model require entrepreneurs to carefully understand the model to ensure that the design competition pursued is “legal” [

7], which drives entrepreneurs to widely collect information about the dominant model. When they have rich-enough general schemas, they will find that the dominant business model is not fixed, and, on the contrary, it should be partially adjusted continuously to maintain its superiority [

14]. Such partial adjustment presents a tipping point in cognitive change at the cognitive level. Before reaching the tipping point, entrepreneurs need to consider how to better adapt to the dominant model, which requires them to collect information within the industry to continuously enrich the information base of the dominant model and improve its effectiveness [

21].

Accordingly, a hypothesis is proposed in this paper as follows:

Hypothesis 2a. General cognitive schemas negatively affect unfamiliar field scanning.

Hypothesis 2b. General cognitive schemas negatively affect outside industry field scanning.

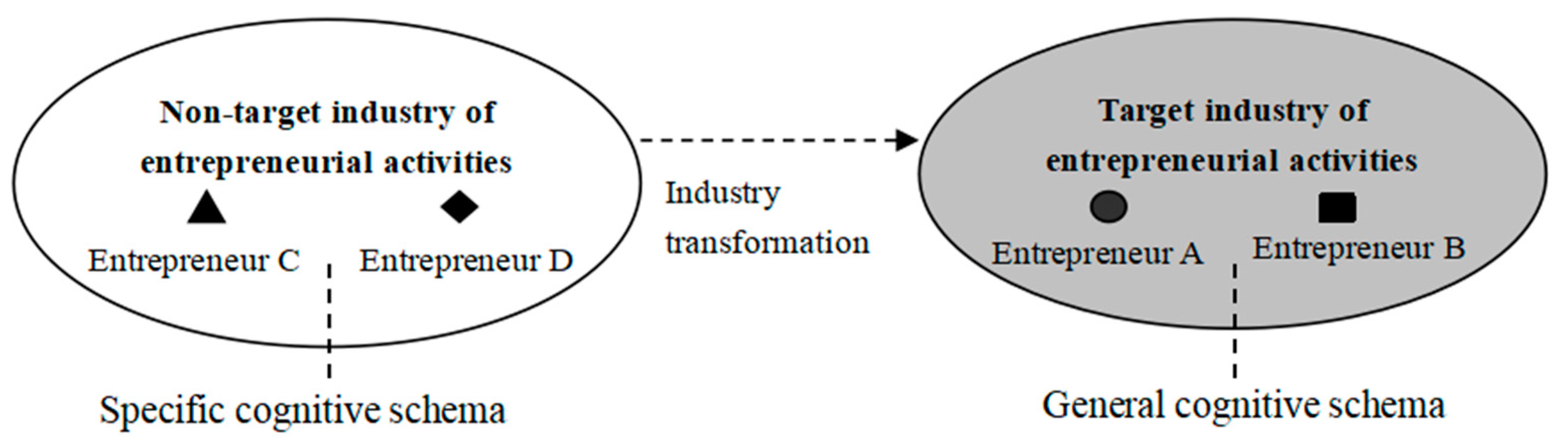

The business model designs that specific cognitive schemas bring to entrepreneurs are not from, or even may not be suitable for, the current entrepreneurial activities in the target industry. These designs also have institutional attributes, and entrepreneurs are very familiar with and have benefited from them for a long time so that they will not give them up easily [

8]. They have to work hard to find the entry point to effectively apply these designs through collecting unfamiliar information from the industry. Entrepreneurs collect information about the industry just to know about the industry, but they do not agree with the dominant business model in the industry. Cliff argued that to question the dominant business model is the beginning of the development of new models, which is usually initiated by entrepreneurs with experience outside the industry [

20]. However, despite knowing that they need to “get rid of the constraint of the dominant business model”, entrepreneurs do not have a specific ultimate goal to “create a new business model” [

29]. It is difficult for them to precisely locate the key information and determine how to use the information from different sources. Therefore, they have to refer to the business model design logic of multiple industries to conduct experimental activities, and to validate relevant hypotheses requires more industries to be scanned [

4].

Accordingly, a hypothesis is proposed in this paper as follows:

Hypothesis 2c. Specific cognitive schemas positively affect unfamiliar field scanning.

Hypothesis 2d. Specific cognitive schemas positively affect outside industry field scanning.

New information and knowledge from unfamiliar and outside industry fields provide entrepreneurs with a new perspective on business models, which provides them with the opportunity to extensively know about the business models of other industries, identify the deficiencies in the dominant business model in the target industry and the opportunities for correction question the rationality of the dominant model and remove its “mythical” status [

20]. With the input of new information and knowledge, entrepreneurs tend to use creative methods, such as analogical reasoning and the connectivity concept, to connect the new information and knowledge to the existing knowledge structure to build a highly innovative business model that can replace the dominant business model in the target industry [

22,

31]. However, when entrepreneurs focus on the familiar information within their industry, it is difficult for them to learn information about business models in other industries, so that they cannot develop a feasible alternative to the dominant business model in the target industry. Moreover, with the continuous increase in experience in the industry, entrepreneurs will excessively rely on and apply the familiar cognitive schemas related to the dominant business models in the industry and form cognitive inertia, which will restrict the willingness and ability of entrepreneurs to design highly innovative business models [

30].

Accordingly, a hypothesis is proposed in this paper as follows:

Hypothesis 3a. Unfamiliar field scanning positively affects business model innovativeness.

Hypothesis 3b. Outside industry field scanning positively affects business model innovativeness.

Combined with the above analysis, from the perspective of cognitive schemas, entrepreneurs with more general cognitive schema are more likely to design low innovative business models, and tend to carry out fewer environmental scanning activities in unfamiliar and outside industry fields, while entrepreneurs with more specific cognitive schema are more likely to design highly innovative business models and tend to carry out more environmental scanning activities in unfamiliar and outside industry fields. From the perspective of environmental scanning, entrepreneurs who tend to carry out environmental scanning activities in unfamiliar and outside industry fields are more likely to design highly innovative business models and vice versa. Based on this, the mediating effect hypothesis is proposed in this paper as follows:

Hypothesis 4a. Unfamiliar field scanning plays a mediating role between general cognitive schema and business model innovativeness.

Hypothesis 4b. Outside industry field scanning plays a mediating role between general cognitive schema and business model innovativeness.

Hypothesis 4c. Unfamiliar field scanning plays a mediating role between specific cognitive schema and business model innovativeness.

Hypothesis 4d. Outside industry field scanning plays a mediating role between specific cognitive schema and business model innovativeness.

2.3.2. The Mediating Effect of Environmental Scanning Intensity

General cognitive schema prevents entrepreneurs from investing a lot of time and energy in environmental scanning activities, which is mainly due to the isomorphism mechanism of institutional attributes of dominant business models. On the one hand, combined with the mimetic isomorphism mechanism, new ventures usually face high uncertainty in the early stage of establishment. Imitating the business model of the incumbents is an effective means to reduce uncertainty because the incumbents’ business model is the dominant model in the industry, which means entrepreneurs do not have to collect additional information to confirm its legality. On the other hand, combined with the coercive isomorphism mechanism and normative isomorphism mechanism, the business model designed by entrepreneurs should meet the expectations of stakeholders in this industry and social culture [

21]. It means that there is a common standard, namely the dominant business model in the industry, to measure whether the new ventures’ business model is suitable or not. This means that it is safe to develop a business based on the dominant business model. General cognitive schemas make entrepreneurs more willing to accept the standard and not too proactive in collecting new information to challenge the dominant business model.

Based on the above analysis, a hypothesis is proposed in this paper as follows:

Hypothesis 5a. General cognitive schema negatively affects the effort level of scanning.

Hypothesis 5b. General cognitive schema negatively affects the sustainability level of scanning.

A specific cognitive schema makes entrepreneurs disagree with the dominant business model in the industry and try to revise and even subvert the model. Changing the dominant business model is an institutional change action, which is not easy. Entrepreneurs need to collect and understand a large amount of information inside and outside the industry to form new knowledge to prove to stakeholders the disadvantages of the dominant model and the advantages of the new model [

30]. For example, Denicolai believed that to realize business model innovation, enterprises should not only pay attention to the accumulation of their own experience and knowledge but also need to constantly acquire new knowledge from the outside, and then connect all of this in novel ways [

32]. According to the neo-institutional theory of organization, institutional change cannot be achieved overnight, and it will go through crucial links, such as de-institutionalization, pre-institutionalization, theorization, diffusion and strengthening institutionalization. Actors need to pay attention to different environmental information in different links and carry out different reform activities [

29]. According to such a view, the highly innovative business model design process also includes more sub-processes, which are usually known as the different phases of learning in business model research. Each phase has a specific task in knowledge accumulation, and the lack of any phase will produce huge damage to the overall design process, which means that environmental scanning activities must be carried out for a long time.

Accordingly, a hypothesis is proposed in this paper as follows:

Hypothesis 5c. Specific cognitive schemas positively affect the effort level of scanning.

Hypothesis 5d. Specific cognitive schemas positively affect the sustainability level of scanning.

The high level of effort and sustainability of entrepreneurial scanning means that they will allocate more attention resources to environmental scanning activities, which can reduce the cognitive bias due to limited attention resources [

31]. The reduction in cognitive bias makes it possible for entrepreneurs to develop a variety of feasible business model designs after systematically analyzing information from different sources. With an increase in available options, entrepreneurs are more likely to design highly innovative business models [

4]. For example, research from Chesbrough (2010) [

8] suggests that highly innovative business models come from the experimental process. Because they do not figure out “whether to innovate” or “how to innovate”, and take the uncertainty of innovation results and the resistance stakeholders possibly develop into consideration, entrepreneurs usually experiment with varieties of business models at the same time and then choose the new final one according to the experimental results. Further, continuous environmental scanning activities also help entrepreneurs improve their capabilities to creatively process information, making them more likely to design highly innovative business models.

Accordingly, a hypothesis is proposed in this paper as follows:

Hypothesis 6a. The effort level of scanning positively affects business model innovativeness.

Hypothesis 6b. The sustainability level of scanning positively affects business model innovativeness.

Combined with the above analysis, from the perspective of cognitive schemas, entrepreneurs with a more general cognitive schema are more likely to design low innovative business models and tend to devote much less effort to environmental scanning activities, and the scanning activities are also not sustained. Entrepreneurs with a more specific cognitive schema are more likely to design highly innovative business models and will be very diligent and persistent in carrying out environmental scanning activities. From the perspective of environmental scanning, entrepreneurs who tend to carry out environmental scanning activities diligently and persistently are more likely to design highly innovative business models and vice versa. Based on this, the mediating effect hypothesis is proposed in this paper as follows:

Hypothesis 7a. The effort level of scanning plays a mediating role between general cognitive schema and business model innovativeness.

Hypothesis 7b. The sustainability level of scanning plays a mediating role between general cognitive schema and business model innovativeness.

Hypothesis 7c. The effort level of scanning plays a mediating role between specific cognitive schema and business model innovativeness.

Hypothesis 7d. The sustainability level of scanning plays a mediating role between specific cognitive schema and business model innovativeness.

The research model is shown in

Figure 2.