Digital Marketing’s Impact on Rural Destinations’ Image, Intention to Visit, and Destination Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Systematic Literature Review

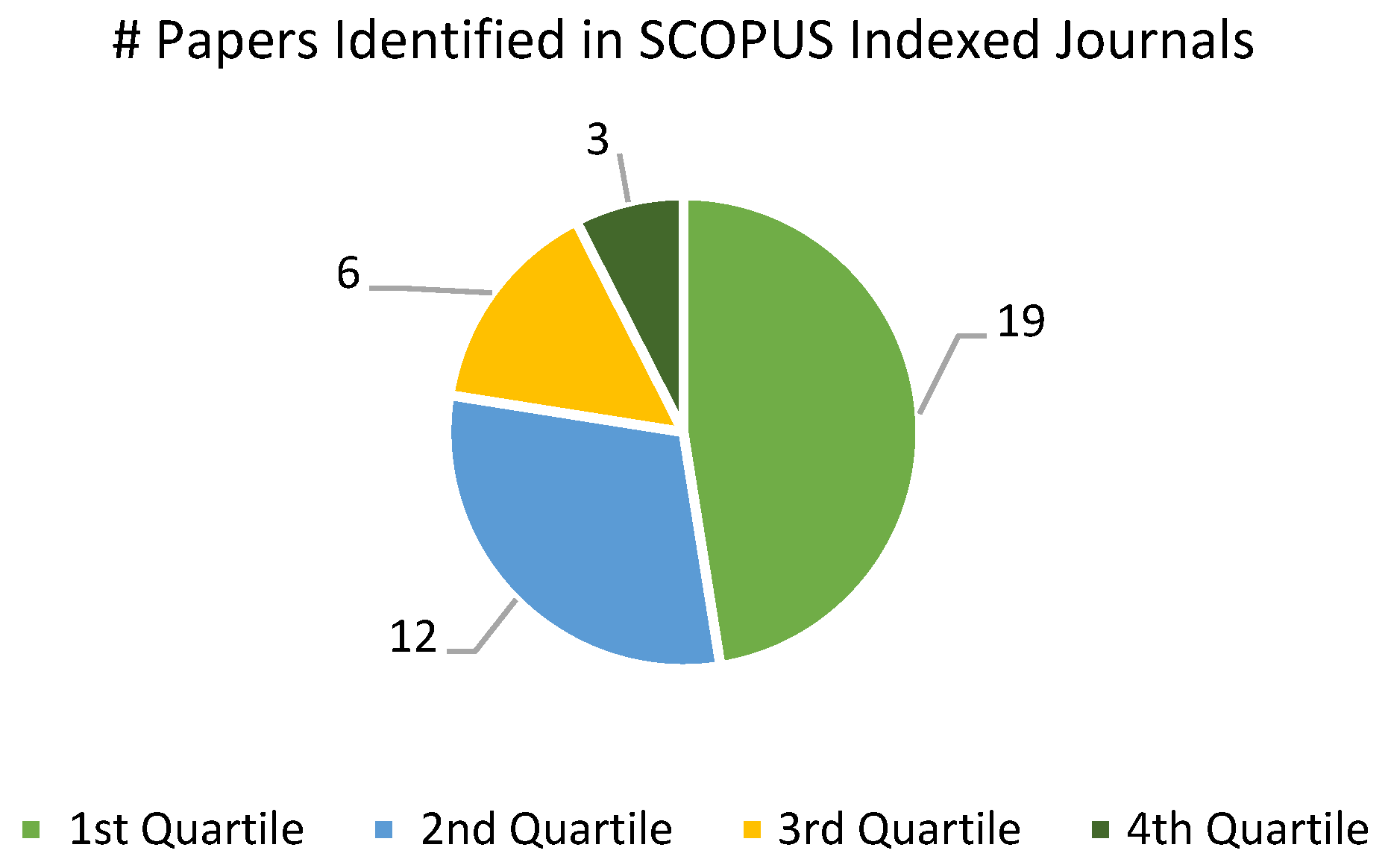

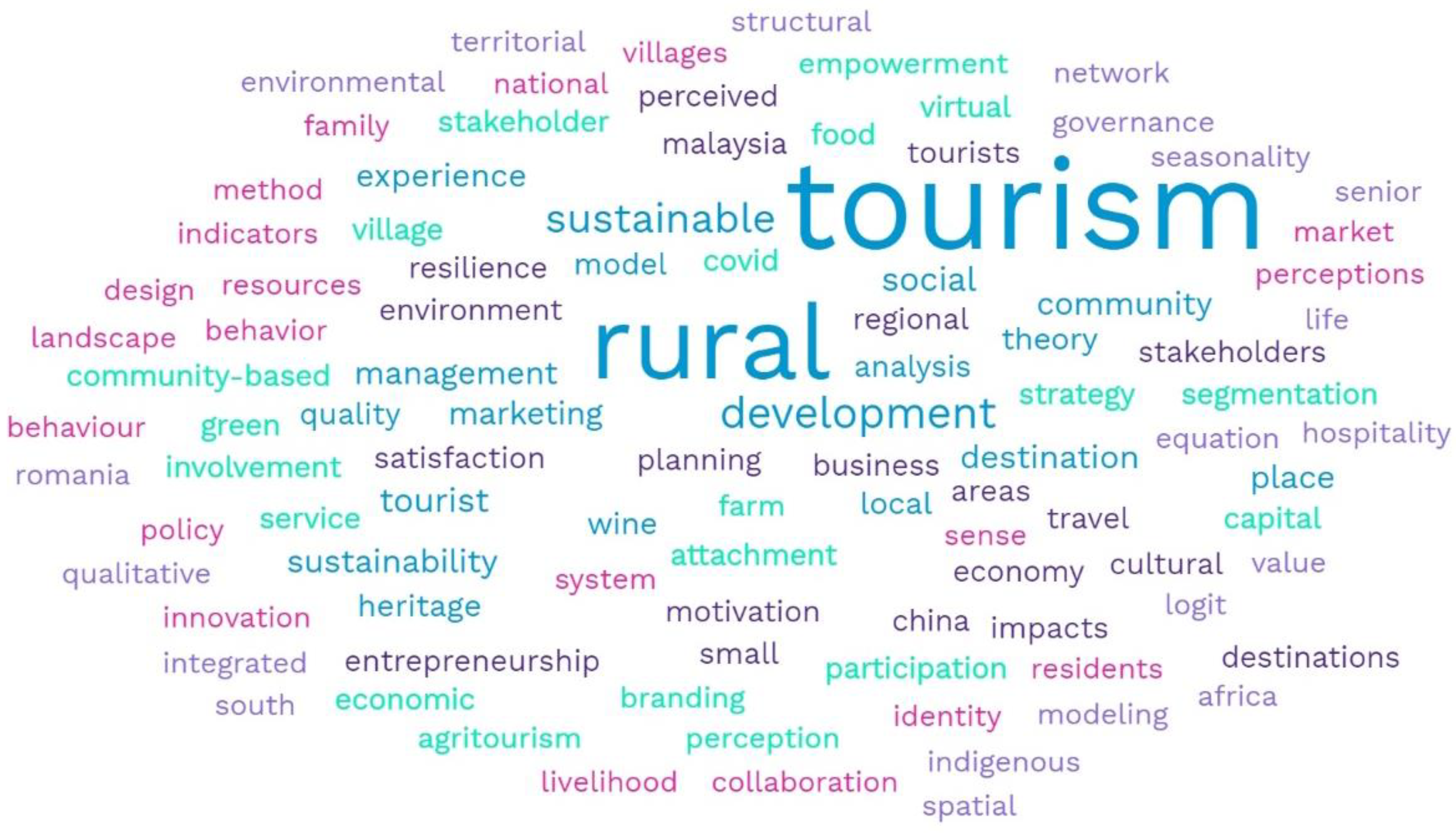

2.1. Initial Results

2.2. Rural Tourism

2.3. Digital Marketing—From Technology to Purpose

2.4. Tourism Destination Image

2.5. Tourists’ Perceived Intention to (re)Visit Tourism Destinations

2.6. Rural Destination Sustainability

3. Adoption and Use of ICT

3.1. The Information System Success Model

3.2. Destination Brand Equity Framework

3.3. Relationships between Destinations’ Familiarity, Image, and Tourists’ Visit Intentions

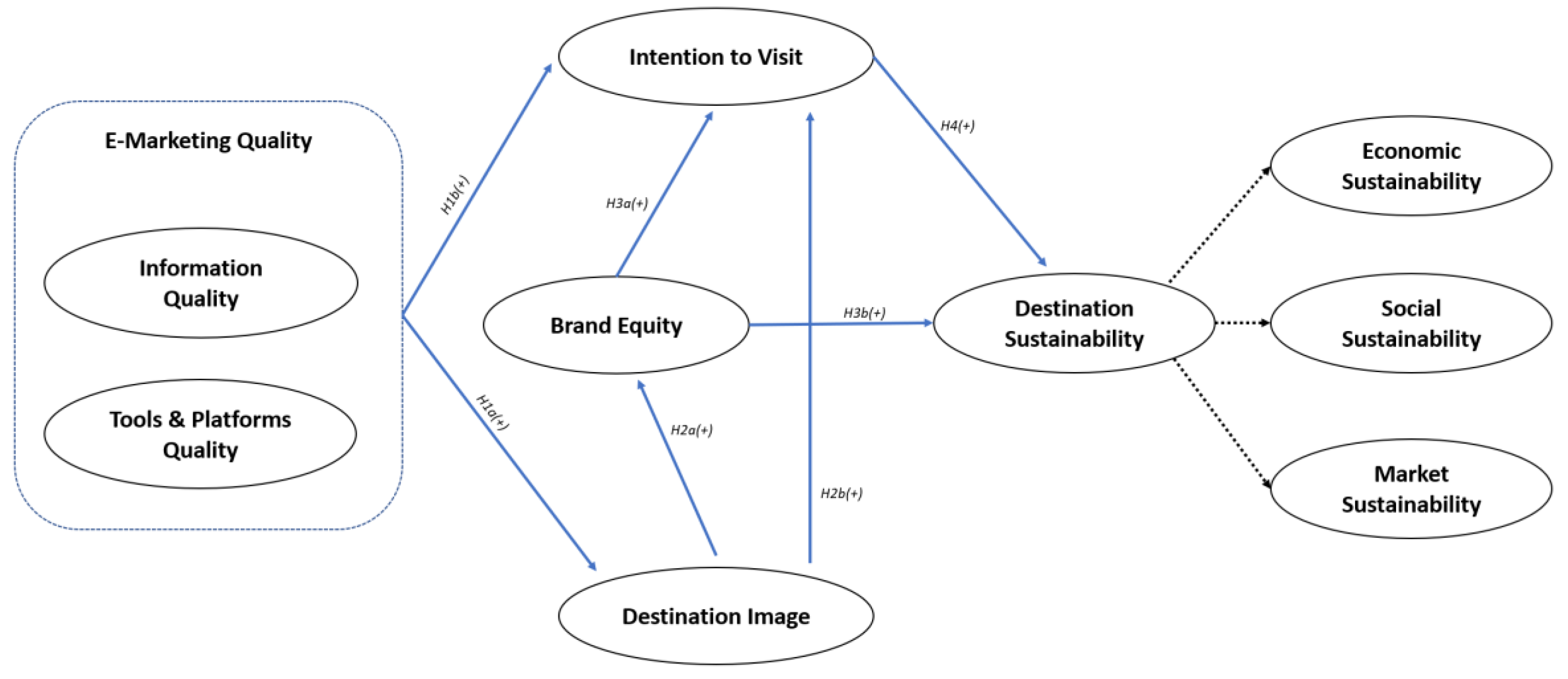

4. Conceptual Model

4.1. Hypothesis Model

4.1.1. e-Marketing Quality

4.1.2. Destination Image

4.1.3. Destination Brand Equity

4.1.4. Intention to Visit

4.2. Qualitative Validation of the Proposed Model—Online Focus Group

4.2.1. Context

4.2.2. Online Focus Group Characterisation

4.2.3. Participants Characterisation

4.2.4. Study Characterisation

4.2.5. Data Collection

4.3. Online Focus Group Results

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Almeida, M.A.P. Territorial Inequalities: Depopulation and Local Development Policies in the Portuguese Rural World. Territ. Inequalities Depopulation Local Dev. Policies Port. Rural. World 2017, 22, 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing Traditional Villages through Rural Tourism: A Case Study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghetti, V.; Buhalis, D. Digital Divide in Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2009, 49, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, L.; Williams, F. Remote Rural Home Based Businesses and Digital Inequalities: Understanding Needs and Expectations in a Digitally Underserved Community. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, W.; Rader, S.; Lanier, C. The “Digital Divide” for Rural Small Businesses. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2017, 19, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K. Forgotten Agritourism: Abandoned Websites in the Promotion of Rural Tourism in Poland. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P.K.; Li, H. “Alice” Digital Marketing: A Framework, Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2017, 34, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, R.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Z. The Effects of Motivation, Destination Image and Satisfaction on Rural Tourism Tourists’ Willingness to Revisit. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pratt, S. Social Media Influencers as Endorsers to Promote Travel Destinations: An Application of Self-Congruence Theory to the Chinese Generation Y. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 958–972. [Google Scholar]

- Christou, P.; Sharpley, R. Philoxenia Offered to Tourists? A Rural Tourism Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.; Martín, J.; Fernández, J.; Mogorrón-Guerrero, H. An Analysis of the Stability of Rural Tourism as a Desired Condition for Sustainable Tourism. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Della Lucia, M. Engaging Destination Stakeholders in the Digital Era: The Best Practice of Italian Regional DMOs. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 43, 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, G.; Trudel, M.-C.; Jaana, M.; Kitsiou, S. Synthesizing Information Systems Knowledge: A Typology of Literature Reviews. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Pires, R. Technological Innovation in Hotels: Open the “Black Box” Using a Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Education Excellence and Innovation Management: A 2025 Vision to Sustain Economic Development during Global Challenges, Seville, Spain, 1–2 April 2020; pp. 6770–6779. [Google Scholar]

- Ovčjak, B.; Heričko, M.; Polančič, G. Factors Impacting the Acceptance of Mobile Data Services—A Systematic Literature Review. Comput. Human Behav. 2015, 53, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Sánchez, A.; Álvarez-García, J.; del Río-Rama, M.C.; Rosado-Cebrián, B. Science Mapping of the Knowledge Base on Tourism Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Miskon, S.; Alkanhal, T.A.; Tlili, I. Modeling of Business Intelligence Systems Using the Potential Determinants and Theories with the Lens of Individual, Technological, Organizational, and Environmental Contexts-a Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keele, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Technical Report, Version 2.3 EBSE Technical Report; EBSE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda, S.; Cravero, A.; Cachero, C. Requirements Modeling Languages for Software Product Lines: A Systematic Literature Review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2016, 69, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paresishvili, O.; Kvaratskhelia, L.; Mirzaeva, V. Rural Tourism as a Promising Trend of Small Business in Georgia: Topicality, Capabilities, Peculiarities. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2017, 15, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Correia, R.F.; Martins, J. Digital Marketing Impact on Rural Destinations Promotion: A Conceptual Model Proposal. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Chaves, Portugal, 23–26 June 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzigeorgiou, C.; Christou, E. Promoting Agrotourism Resorts Online: An Assessment of Alternative Advertising Approaches. Int. J. Technol. Mark. 2020, 14, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Gonçalves, R.; Martins, J.; Branco, F. The Social Impact of Technology on Millennials and Consequences for Higher Education and Leadership. Telemat. Informatics 2018, 35, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, K.K.; Kalro, A.D.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, P. A Typology of Viral Ad Sharers Using Sentiment Analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, M.; Verma, D. A Critical Review of Digital Marketing. Crit. Rev. Digit. Mark. Int. J. Manag. IT Eng. 2018, 8, 321–339. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffey, D.; Ellis-Chadwick, F. Digital Marketing; Pearson: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 1292241624. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu, D.; Militaru, G.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Niculescu, A.; Popescu, M.A. A Perspective Over Modern SMEs: Managing Brand Equity, Growth and Sustainability Through Digital Marketing Tools and Techniques. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.A. Vacationscape: Designing Tourist Regions; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 0442226799. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, S.; González, F. The Importance of Quality, Satisfaction, Trust, and Image in Relation to Rural Tourist Loyalty. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Zehrer, A.; Müller, S. Perceived Destination Image: An Image Model for a Winter Sports Destination and Its Effect on Intention to Revisit. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelt, N.G.; Benito, J.A.D. The Social Construction of the Image of Girona: A Methodological Approach. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Oom do Valle, P.; da Costa Mendes, J. The Cognitive-Affective-Conative Model of Destination Image: A Confirmatory Analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.L.; Lee, J.-S. Toward the Perspective of Cognitive Destination Image and Destination Personality: The Case of Beijing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kim, J.; Jang, H.; Lee, S. The Roles of Categorization, Affective Image and Constraints on Destination Choice: An Application of the NMNL Model. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 750–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cai, L.A.; Lehto, X.Y.; Huang, J. A Missing Link in Understanding Revisit Intention—The Role of Motivation and Image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination Image and Tourist Behavioural Intentions: A Meta-Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, N.; Skinner, H. The Importance of Destination Image Analysis to UK Rural Tourism. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S. The Role of the Rural Tourism Experience Economy in Place Attachment and Behavioral Intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacob, S.; Johannes, J.; Qomariyah, N. Visiting Intention: A Perspective of Destination Attractiveness and Image in Indonesia Rural Tourism. Sriwij. Int. J. Dyn. Econ. Bus. 2019, 3, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbarian, B.; Pool, J.K. The Impact of Perceived Quality and Value on Tourists’ Satisfaction and Intention to Revisit Nowshahr City of Iran. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.; Abdullah, S.K.; Islam, F.; Neela, N.M. An Integrated Model for Examining Tourists’ Revisit Intention to Beach Tourism Destinations. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 716–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Correia, R.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F.; Martins, J. e-Marketing Influence on Rural Tourism Destination Sustainability: A Conceptual Approach BT. In Information Systems and Technologies; Rocha, A., Adeli, H., Dzemyda, G., Moreira, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 449–461. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable Tourism Development: A Critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; McKercher, B.; Suntikul, W. Identifying Core Indicators of Sustainable Tourism: A Path Forward? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.F.B.; Virto, N.R.; Manzano, J.A.; Miranda, J.G.-M. Residents’ Attitude as Determinant of Tourism Sustainability: The Case of Trujillo. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 35, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Andrades-Caldito, L.; Sánchez-Rivero, M. Is Sustainable Tourism an Obstacle to the Economic Performance of the Tourism Industry? Evidence from an International Empirical Study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturas, B. Models of Acceptance and Use of Technology: Research Trends in the 21st Century. In Proceedings of the CAPSI 2019, Lisbon, Portugal, 11–12 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Malhotra, N.K. A Longitudinal Model of Continued IS Use: An Integrative View of Four Mechanisms Underlying Postadoption Phenomena. Manage. Sci. 2005, 51, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Measuring E-Commerce Success: Applying the DeLone & McLean Information Systems Success Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2004, 9, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bédard, F.; Louillet, M.C.; Verner, A.; Joly, M.-C. Implementation of a Destination Management System Interface in Tourist Information Centres and Its Impact. Inf. Commun. Technol. Tour. 2008, 220–231. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, P. The Effect of Brand Engagement and Brand Love upon Overall Brand Equity and Purchase Intention: A Moderated–Mediated Model. J. Promot. Manag. 2021, 27, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.H.; Kim, S.S.; Elliot, S.; Han, H. Conceptualizing Destination Brand Equity Dimensions from a Consumer-Based Brand Equity Perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C.; Ruzzier, M.K. Tourism Destination Brand Equity Dimensions: Renewal versus Repeat Market. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Sánchez, M.I.; Sánchez, J. Tourism Image, Evaluation Variables and after Purchase Behaviour: Inter-Relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A Model of Destination Branding: Integrating the Concepts of the Branding and Destination Image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-K.; Wu, C.-E. An Investigation of the Relationships among Destination Familiarity, Destination Image and Future Visit Intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumer, S.; Maier, C.; Weitzel, T. Information Quality, User Satisfaction, and the Manifestation of Workarounds: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study of Enterprise Content Management System Users. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-E.; Lee, K.Y.; Shin, S.I.; Yang, S.-B. Effects of Tourism Information Quality in Social Media on Destination Image Formation: The Case of Sina Weibo. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotoua, S.; Ilkan, M. Tourism Destination Marketing and Information Technology in Ghana. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.-S. Tourism Destination Image Modification Process: Marketing Implications. Tour. Manag. 1991, 12, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladou, S.; Kehagias, J. Assessing Destination Brand Equity: An Integrated Approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G. Measuring Empowerment: Developing and Validating the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS). Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.; Oliveira, T. Understanding the Impact of M-Banking on Individual Performance: DeLone & McLean and TTF Perspective. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 61, 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, J.; Branco, F.; Gonçalves, R.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Oliveira, T.; Naranjo-Zolotov, M.; Cruz-Jesus, F. Assessing the Success behind the Use of Education Management Information Systems in Higher Education. Telemat. Informatics 2019, 38, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, O.; Abdullah, Z.; Ramayah, T.; Mutahar, A.M. Factors Determining User Satisfaction of Internet Usage among Public Sector Employees in Yemen. Int. J. Technol. Learn. Innov. Dev. 2018, 10, 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; Kao, C.-Y. Website Quality and Customer’s Behavioural Intention: An Exploratory Study of the Role of Information Asymmetry. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2005, 16, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S.; Wiitala, J.; Fu, X. The Impact of Country Image and Destination Image on US Tourists’ Travel Intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faircloth, J.B.; Capella, L.M.; Alford, B.L. The Effect of Brand Attitude and Brand Image on Brand Equity. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2001, 9, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; López-Sánchez, Y. Perception of Sustainability of a Tourism Destination: Analysis from Tourist Expectations. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2014, 13, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, M.; Zulhan, O.; Aliffaizi, A.; Mohd, F. Brand Equity and Customer Behavioural Intention: A Case of Food Truck Business. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2017, 9, 561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, S.; Pradhan, S.; Bashir, M.; Roy, S.K. Customer-Based Place Brand Equity and Tourism: A Regional Identity Perspective. J. Travel Res. 2021, 61, 0047287521999465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S.; Martins, J.; Branco, F.; Zolotov, M. An Online Focus Group Approach to E-Government Acceptance and Use. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, Naples, Italy, 27–29 March 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, R.; Martins, J.L.; Branco, F.; Perez Cota, M.; Oliveira, M.A.-Y. Increasing the Reach of Enterprises through Electronic Commerce: A Focus Group Study Aimed at the Cases of Portugal and Spain. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2016, 13, 927–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.E.; Gandha, T.; Culbertson, M.J.; Carlson, C. Focus Group Evidence: Implications for Design and Analysis. Am. J. Eval. 2014, 35, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Martins, J.; Branco, F.; Gonçalves, R.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Moreira, F. A Theoretical Analysis of Digital Marketing Adoption by Startups. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Process Improvement, Zacatecas, Mexico, 18–20 October 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, D.W.; Shamdasani, P. Online Focus Groups. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Branco, F.; Martins, J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Moreira, F.; Gonçalves, R.; Perez-Cota, M.; Jorge, F. Main Factors in the Adoption of Digital Marketing in Startups an Online Focus Group Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Caceres, Spain, 13–16 June 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ghauri, P.; Grønhaug, K.; Strange, R. Research Methods in Business Studies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; ISBN 1108802745. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017; ISBN 1442268867. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobeva, D.; Scott, I.J.; Oliveira, T.; Neto, M. Adoption of New Household Waste Management Technologies: The Role of Financial Incentives and pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeiros, H.; Oliveira, T.; Thomas, M.A. The Impact of IoT Smart Home Services on Psychological Well-Being. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 1009–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Zolotov, M.; Turel, O.; Oliveira, T.; Lascano, J.E. Drivers of Online Social Media Addiction in the Context of Public Unrest: A Sense of Virtual Community Perspective. Comput. Human Behav. 2021, 121, 106784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Araujo, B.; Tam, C. Why Do People Share Their Travel Experiences on Social Media? Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgado-Armenteros, E.M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J.; Vega-Zamora, M. Differences between Online and Face to Face Focus Groups, Viewed through Two Approaches. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 7, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawardani, I.G.A.O.; Wiranatha, A.S. Digital Marketing in Promoting Events and Festivities. A Case of Sanur Village Festival. J. Bus. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 2, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, H.; Shaw, B.R.; Spartz, J.T. Promoting Economic Development with Tourism in Rural Communities: Destination Image and Motivation to Return or Recommend. J. Ext. 2015, 53, 2FEA6. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.; Weaver, P.A. Customer-based Brand Equity for a Destination: The Effect of Destination Image on Preference for Products Associated with a Destination Brand. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwel, S.; Lingqiang, Z.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. The Influence of Destination Image on Tourist Loyalty and Intention to Visit: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumail, T.; Qeed, M.A.A.; Aburumman, A.; Abbas, S.M.; Sadiq, F. How Destination Brand Equity and Destination Brand Authenticity Influence Destination Visit Intention: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. J. Promot. Manag. 2022, 28, 332–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Determinant | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Information quality | Information quality, which is defined as the value of the information that a specific system is capable of keeping, supplying, or generating, is one of the most common dimensions along which information systems are developed. The quality of the information affects how satisfied a user is with the system as well as how likely they are to use it, which in turn affects how the system can benefit both the user and the company. According to a number of scholars, the factors of relevance, opportunity, interest, completeness of the material, and the calibre of the content development process are all important components of tourism-related marketing information’s overall quality. | [59,60,61] |

| Tool and platform quality | E-marketing tool and platform quality is considered decisive for the assessment of a given initiative’s quality, as they tend to impact how the initiative generates added value. High-quality tools and platforms are often the basis for high-quality e-marketing initiatives. Hence, when transposing this to the promotion of tourism destinations, it is also essential to assess the positive impacts that the structural quality of an e-marketing initiative might have on both the tourism destination and its tour operators. | [60,62] |

| Destination image | The main subjects of study are how the idea of a tourism destination affects travellers’ choices and how it relates to marketing strategies. This idea has been prevalent in the literature for a number of decades. We can characterise the image of a tourism destination as being built in three distinct moments: (a) pre-visit, (b) during the visit, and (c) post-visit. | [32,63] |

| Brand wquity | A number of elements make up the concept of destination brand equity, including image, awareness, loyalty, and overall quality. It is related to customer brand knowledge and has also been the subject of numerous authors’ studies. Tourists’ behavioural intention to travel might be affected if there is a favourable perception of the brand equity of a particular tourism destination. | [53,64] |

| Intention to visit | The relationship between visitors’ views of a location and the value of those perceptions has a significant impact on their intention to travel there. A rural tourism destination’s chances of inciting people to visit and recommend it again are generally boosted when it can effectively communicate its worth. | [38,40] |

| Destination sustainability | A destination’s sustainability can be viewed as a collection of various elements, including market, social, and economic sustainability. The literature also discusses the direct effects of these three factors—which are outlined as the fundamental tenets of sustainable tourism—on the economy, society, and environment. | [46,65] |

| Activity Sector | Experience (Years) | Academic Degree | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSSTHE | Public Sector | Private Sector | 0–5 | 5–10 | >10 | Degree | Master’s Degree | PhD |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Determinant | 1 (Not Important) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 (Very Important) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information quality | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.5% | 12.5% | 50.0% | 25.0% |

| Tool and platform quality | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37.5% | 50.0% | 12.5% |

| Destination image | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.5% | 37.5% | 50.0% |

| Destination brand equity | 0 | 0 | 12.5% | 37.5% | 25.0% | 25.0% | 0 |

| Intention to visit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37.5% | 37.5% | 25.0% |

| Hypothesis | 1 (Not Adequate) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 (Very Adequate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 62.5% | 37.5% |

| H1b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 62.5% | 37.5% |

| H2a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.5% | 75.0% | 12.5% |

| H2b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.5% | 75.0% | 12.5% |

| H3a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0 |

| H3b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0 |

| H4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37.5% | 62.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, S.; Correia, R.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F.; Martins, J. Digital Marketing’s Impact on Rural Destinations’ Image, Intention to Visit, and Destination Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032683

Rodrigues S, Correia R, Gonçalves R, Branco F, Martins J. Digital Marketing’s Impact on Rural Destinations’ Image, Intention to Visit, and Destination Sustainability. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032683

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Sónia, Ricardo Correia, Ramiro Gonçalves, Frederico Branco, and José Martins. 2023. "Digital Marketing’s Impact on Rural Destinations’ Image, Intention to Visit, and Destination Sustainability" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032683

APA StyleRodrigues, S., Correia, R., Gonçalves, R., Branco, F., & Martins, J. (2023). Digital Marketing’s Impact on Rural Destinations’ Image, Intention to Visit, and Destination Sustainability. Sustainability, 15(3), 2683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032683