Defining a Social Role for Ports: Managers’ Perspectives on Whats and Whys

Abstract

:1. Introduction

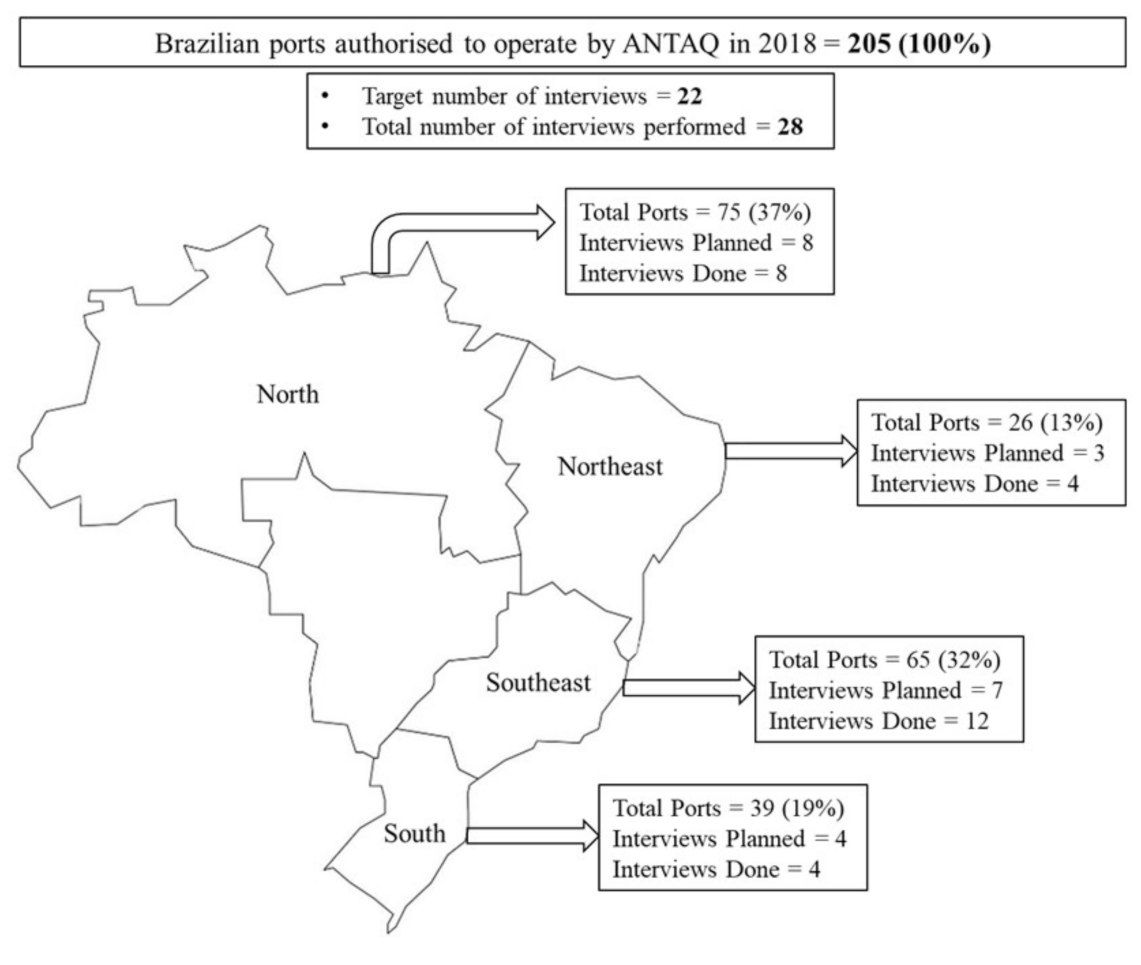

2. Review of the Literature

Q1—What are the social roles of ports?

Q2—Why should ports adopt a social role?

3. Methodology

4. Analysis Results

4.1. The Social Role of Ports

4.1.1. Port as a Regional Developer of the Social Environment

“ports must be connected to the region where they are, and they must become part of the social context of the region, allowing their existence to create value for the social environment where they are inserted.”

“Often, the regional development role is miscomprehended with the role of the public entities that should be in charge of the welfare of the city inhabitants. The port tries to offer help and becomes solely responsible for matters such as school education or health assistance. Therefore, a clear separation of the social role of the port does not create a dependency that the business later cannot sustain. In this case, once resources become scarce, it becomes the port’s responsibility if people do not have schools or health services available. “

4.1.2. Adapting Ports’ Processes to Achieve Social Objectives

“managers (of ports) need to be absolutely aware of the transformations they are creating in the surroundings, and they need to respect those who live in the area and adapt the port processes to do what is expected by stakeholders.”

“the port needs to grow, become productive and respect the stakeholders and the natural environment where they are located. This transformational mentality has to come from the highest levels of the organisation and be cascaded to the lower levels.”

“the port or any other organisation must understand the impact that it causes on the surrounding society. These can be economic, environmental, or anything disturbing the region’s social balance. This is the biggest role that the port has in the social dimension. Once these impacts are known, the port can adapt its actions to cope with the stakeholders’ demands.”

4.1.3. The Improvement of the Economic Status of the Region

4.1.4. The Leadership Role

“The port is part of the production chain that includes many other industries. Especially in the case where the port is a cluster of different enterprises, I see the social role of the port as a leader to promote solutions for the common problems that affect the stakeholders around it. “

4.1.5. Maximise the Port’s Economic Capabilities to Provide Social Betterment

“Considering the function of the port to concentrate cargo, the high traffic of vessels and vehicles created by its activities can affect the stakeholders negatively. Therefore, it is necessary to optimise the way the port operates to ensure that no risks are created for the community in terms of the safety of people and the protection of the natural environment. So the level of services has to match the requirements that balance the economic, environmental and social benefits created. “

4.2. Reasons for Adopting a Social Role

4.2.1. The Social Accountability of the Port

“It is inevitable. Every enterprise, considering its size, creates impacts that affect the stakeholders around it. These impacts can occur differently and modify how people around the port leave. Fixing this disturbance becomes, therefore, part of the port’s responsibility.”

“Impacts created by the port are significant, and they refer to the land use, impact on the region’s economic activities, and impact on stakeholders’ quality of life. The port transforms the region where it is installed, and this transformation can echo far away to the regions connected by the port activity. Therefore, the port is accountable for ensuring that these changes can mutually benefit all those linked to its activities.”

4.2.2. The Need for Stakeholders’ Support

“we must have the overall stakeholders, internal and external, supporting the organisation. It must be avoided that they have a negative opinion about the business. Otherwise, the organisation can be affected during licensing processes and, for example, face barriers with plans to expand the port activities in the region’.”

“In the past, the social dimension was considered a pro-forma aspect of the business, oriented to compliance with laws and regulations. Today, the support of stakeholders helps with the legal licenses to operate but also ensures that the port can exist with the consent of those affected by its activities. “

4.2.3. Strategic Development

“looking at what happened in the last years, the adoption of the social roles shifted from a pro-forma approach to a survival need. The former model in which we needed to comply with regulations is in the past. Nowadays, we can only survive in the long run if stakeholders issue the enterprise’s social license to operate.”

4.2.4. Prevention of Problems Escalation

“If you do not have the social dimension of business managed initially, the port operations will be impacted and suffer the consequences in a later stage. It can occur in the form of interruptions to the operations caused by public demonstrations that block access to the port, legal interruptions imposed by local authorities or even the reduction in investments caused by the negative image of the business. Overall, no problem or issue should be ignored; otherwise, the risk of becoming unmanageable is too high.”

4.2.5. Compliance with Laws and Regulations

4.2.6. Return for the Exploitation of Resources

“the company uses natural resources that belong to the state, in other words, to society, and transforms that into profit to a certain group of stakeholders. This is unacceptable unless the benefits are shared with the overall people affected by the port activity.”

5. Discussion of Findings

5.1. The Social Accountability of Ports

“expanding the richness of human life rather than simply the richness of the economy in human beings live. It is an approach that is focused on people and their opportunities and choices [97].”

5.2. The Capacity to Use the Best of the Port’s Skills in the Social Dimension

“Ports can hire professionals that can offer a different understanding of the social dimension. These professionals can bring new ideas on board and educate the organisation about what needs to be done in the social dimension. The biggest challenge in this sense is to ensure that funds and resources are secured to guarantee that this can become a sustained action carried out by the organisation. “

5.3. The Strategic Reasoning for Adopting Social Roles

“The question now is not if ports will need to look at the social dimension of businesses but how they will lead the initiative and put together financial and human resources to manage the social impacts created. From a strategic point of view, the proactive approach can prevent authorities and other stakeholders from overreacting if an issue affects them. In other words, it is better to build strategic alliances in advance than wait and see what can happen.”

5.4. The Moral Responsibility Motivation

5.5. The Compulsory Reasons to Adopt a Social Role

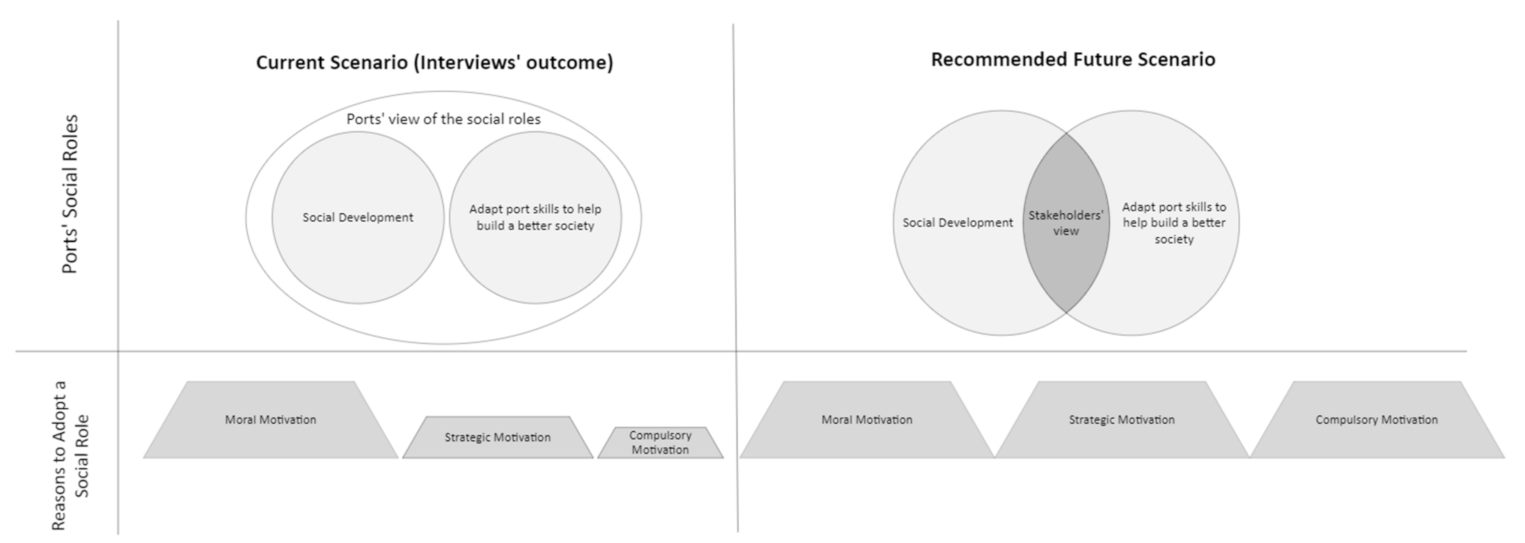

5.6. Current and Future Scenarios Analysis

6. Conclusions and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bosak, J. Social Roles. In Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science; Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate Social Performance Revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodaghi, A.; Oliveira, J. The theater of fake news spreading, who plays which role? A study on real graphs of spreading on Twitter. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 189, 116110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, S.; Kujala, J. Stakeholder Engagement in Humanizing Business. In Humanising Business: What Humanities Can Say to Business; Dion, M., Freeman, R.E., Dmytriyev, S.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Pettit, S.; Abouarghoub, W.; Beresford, A. Port sustainability and performance: A systematic literature review. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2019, 72, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanelslander, T. Port CSR: Innovation for economic, social and environmental objectives. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciaro, M. Corporate responsibility and value creation in the port sector. Int. J. Logist.-Res. Appl. 2015, 18, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, S.; Becker, A.; Ng, A.K.Y. Seaport adaptation for climate change—The roles of stakeholders and the planning process. In Climate Change and Adaptation Planning for Ports; Adolf, K.Y., Ng, A.B., Cahoon, S., Chen, S.-L., Earl, P., Yang, Z., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; Chapter 2; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Aerts, G.; Dooms, M.; Haezendonck, E. Stakeholder management practices found in landlord port authorities in Flanders: An inside-out perspective. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2015, 7, 597–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.S.L.; Li, K.X. Green port marketing for sustainable growth and development. Transp. Policy 2019, 84, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooms, M. Stakeholder Management for Port Sustainability: Moving From Ad-Hoc to Structural Approaches. In Green Ports; Rickard Bergqvist, J.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, M.H.; Yang, Z.; Notteboom, T.; Ng, A.K.Y.; Heo, M.W. Revisiting port performance measurement: A hybrid multi-stakeholder framework for the modelling of port performance indicators. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 103, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notteboom, T.; Winkelmans, W. Dealing with Stakeholders in the Port Planning Process. Across the Border: Building upon a Quarter of Century of Transport Research in the Benelux; De Boeck: Antwerp, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Geerts, M.; Dooms, M. Sustainability Reporting for Inland Port Managing Bodies: A Stakeholder-Based View on Materiality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Carpenter, A.; Sammalisto, K. Analysing Organisational Change Management in Seaports: Stakeholder Perception, Communication, Drivers for, and Barriers to Sustainability at the Port of Gävle. In European Port Cities in Transition: Moving Towards More Sustainable Sea Transport Hubs; Carpenter, A., Lozano, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, D.; Slack, B. Rethinking the Port. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 38, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.T.W.; Wu, J.Z.; Suthiwartnarueput, K.; Hu, K.C.; Rodjanapradied, R. A Comparative Study of Key Critical Factors of Waterfront Port Development: Case Studies of the Incheon and Bangkok Ports. Growth Chang. 2016, 47, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, H.; Michalska-Szajer, A.; Dąbrowski, J. Corporate social responsibility of the Ports of Szczecin and Świnoujście. Sci. J. Marit. Univ. Szczec. 2020, 61, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, B.-M. Economic Contribution of Ports to the Local Economies in Korea. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2011, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.J.; Costa, J.P. Touristification of European Port-Cities: Impacts on Local Populations and Cultural Heritage. In European Port Cities in Transition: Moving Towards More Sustainable Sea Transport Hubs; Carpenter, A., Lozano, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sakalayen, Q.; Chen, P.S.L.; Cahoon, S. The strategic role of ports in regional development: Conceptualising the experience from Australia. Marit. Policy Manag. 2017, 44, 933–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogué-Algueró, B. Growth in the docks: Ports, metabolic flows and socio-environmental impacts. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, R.O. Economic policies and ports: The economic functions of ports. Marit. Policy Manag. 1990, 17, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Lugt, L.M.; De Langen, P.W.; Hagdorn, L. Value capture and value creation in the ports’ business ecosystem. In Proceedings of the IAME 2007 Conference Proceedings, Athens, Greece, 4–6 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Lugt, L.M.; De Langen, P.W.; Hagdorn, L. Strategic beliefs of port authorities. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 412–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marner, T.; Klumpp, M. Employment effects and efficiency of ports. Int. J. Comput. Aided Eng. Technol. 2020, 12, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, E.; Benacchio, M.; Ferrari, C. Ports and Employment in Port Cities. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 2000, 2, 283–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Soberon, A.M.; Monfort, A.; Sapina, R.; Monterde, N.; Calduch, D. Automation in port container terminals. Xi Congr. De Ing. Del Transp. 2014, 160, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, X.Q.; Vu, V.H.; Hens, L.; Van Heur, B. Stakeholder perceptions and involvement in the implementation of EMS in ports in Vietnam and Cambodia. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chao, Y.; Yang, D. Port recentralization as a balance of interest. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 34, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangan, J.; Cunningham, J. Irish Ports: Commercialisation and Strategic Change. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2008, 11, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, R.; Ferretti, M.; Musella, G.; Risitano, M. Evaluating the economic and environmental efficiency of ports: Evidence from Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, J.P.; Comtois, C.; Slack, B. The Geography of Transport Systems; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Panayides, P.M.; Song, D.W. Port integration in global supply chains: Measures and implications for maritime logistics. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2009, 12, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Nguyen, H.O.; Cahoon, S.; Sakalayen, Q. Regional port development: The case study of Tasmanian Ports, Australia. In Proceedings of the International Association of Maritime Economists 2012 Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 6–8 September 2012; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, D. Spatial Restructuring of Port Cities: Periods from Inclusion to Fragmentation and Re-integration of City and Port in Hamburg. In European Port Cities in Transition: Moving Towards More Sustainable Sea Transport Hubs; Carpenter, A., Lozano, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, N. Os desafios da regulação do setor de transporte no Brasil. Rev. Adm. Pública 2000, 34, 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon, S.; Pateman, H.; Chen, S.-L. Regional port authorities: Leading players in innovation networks? J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 27, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paixão, A.C.; Bernard Marlow, P. Fourth generation ports—A question of agility? Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2003, 33, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciaro, M.; Renken, K.; El Khadiri, N. Technological Change and Logistics Development in European Ports. In European Port Cities in Transition: Moving Towards More Sustainable Sea Transport Hubs; Carpenter, A., Lozano, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bichou, K. Port Operations, Planning and Logistics; Informa Law from Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.M.P.; Salvador, R.; Guedes Soares, C. A dynamic view of the socio-economic significance of ports. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2017, 20, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gripaios, P.; Gripaios, R. The impact of a port on its local economy: The case of Plymouth. Marit. Policy Manag. 1995, 22, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooms, M.; Haezendonck, E.; Verbeke, A. Towards a meta-analysis and toolkit for port-related socio-economic impacts: A review of socio-economic impact studies conducted for ports. Marit. Policy Manag. 2015, 42, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalayen, Q.; Chen, P.S.L.; Cahoon, S. Investigating the strategies for Australian regional ports’ involvement in regional development. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2016, 8, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalayen, Q.; Chen, P.S.L.; Cahoon, S. A place-based approach for ports’ involvement in regional development: A mixed-method research outcome. Transp. Policy 2022, 119, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.J.; Ducruet, C. New port development and global city making: Emergence of the Shanghai-Yangshan multilayered gateway hub. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 25, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terenteva, K.; Vagizova, V.; Selivanova, K. Transport Infrastructure as a Driver of Sustainable Development of Regional Economic Systems. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 15, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bottasso, A.; Conti, M.; Ferrari, C.; Tei, A. Ports and regional development: A spatial analysis on a panel of European regions. Transp. Res. Part A-Policy Pract. 2014, 65, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.; Merkii, O.; Bottasso, A.; Conti, M.; Tei, A. Ports and Regional Development: A European Perspective; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.L.; Van Geenhuizen, M. Port infrastructure investment and regional economic growth in China: Panel evidence in port regions and provinces. Transp. Policy 2014, 36, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowska, I.; Mańkowska, M.; Pluciński, M. Socio-economic Costs and Benefits of Port Infrastructure Development for a Local Environment. The Case of the Port and the City of Świnoujście. In European Port Cities in Transition: Moving Towards More Sustainable Sea Transport Hubs; Carpenter, A., Lozano, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Merk, O.; Hilmolai, O.P.; Dubarle, P. The Competitiveness of Global Port-Cities: The Case of Helsinki, Finland; OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 8; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, S.H. The economic-social performance relationships of ports: Roles of stakeholders and organisational tension. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, S.; Geerlings, H.; El Makhloufi, A. Port governance revisited: How to govern and for what purpose? Transp. Policy 2019, 77, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Zhou, L. Evaluation of Ship Pollutant Emissions in the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Langen, P.W. Towards a Better Port Industry: Port Development, Management and Policy; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M. El impacto sociocultural de las transformaciones en el puerto de Barcelona. Revista Transporte y Territorio 2015, 12, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.; Rosello, M. Fisheries and maritime security: Understanding and enhancing the connection. In Maritime Security and the Law of the Sea; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Ports Primer: 2.1 The Role of Ports. 2017. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ports-initiative/ports-primer-21-role-ports (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Oliveira, L.; Cepik, M.; Brites, P. O pré-sal e segurança do Atlântico Sul: A defesa em camadas e o papel da integração sul-americana. Capa-Revista Da Egn 2016, 20, 139–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kopela, S. Tackling maritime security threats from a port state’s perspective. In Maritime Security and the Law of the Sea; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, G.-T.; Pak, J.-Y.; Yang, Z. Analysis of dynamic effects on ports adopting port security policy. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 49, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.; Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Method Research; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Vaus, D. Research Design in Social Research; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, V.-W. Using Industrial Key Informants: Some Guidelines. Mark. Res. Soc. J. 1994, 36, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F. Working with Corporate Social Responsibility in Brazilian Companies: The Role of Managers’ Values in the Maintenance of CSR Cultures. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, S.E.; Jimmieson, N.L. Middle managers’ uncertainty management during organisational change. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2006, 27, 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, O.C. Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2013, 11, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.A.; Stuart, A. An Experimental Study of Quota Sampling. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A-Stat. Soc. 1953, 116, 349–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Turner, L.A. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2016, 1, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.D.; Zhou, Q.Y. Exploring the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Leadership Identity Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, W.S. Strategies for conducting elite interviews. Qual. Res. 2011, 11, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.A.; Miller, M.K. Phone interviewing as a means of data collection: Lessons learned and practical recommendations. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2001, 2, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, S.A.; Furgerson, S.P. Writing interview protocols and conducting interviews: Tips for students new to the field of qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2012, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazeley, P.; Jackson, K. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo; Sage Publications Limited: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M.; Delahunt, B. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J All Irel. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2017, 9, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, J. Qualitative Researching; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data; Sage Publication Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G. Analysing Qualitative Data; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M.; Barroso, J. Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qual. Health Res. 2003, 13, 905–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desantis, L.; Ugarriza, D.N. The concept of theme as used in qualitative nursing research. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2000, 22, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L.M. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Temple, B.; Young, A. Qualitative research and translation dilemmas. Qual. Res. 2004, 4, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Liu, J. Sustainable port cities with coupling coordination and environmental efficiency. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 205, 105534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’amico, G.; Szopik-Depczynska, K.; Dembinska, I.; Ioppolo, G. Smart and sustainable logistics of Port cities: A framework for comprehending enabling factors, domains and goals. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouili, T.A. Impact of Port Infrastructure, Logistics Performance, and Shipping Connectivity on Merchandise Exports. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2019, 19, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, L.Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.L.; Xu, H.F.; Li, L. The role of ports in the economic development of port cities: Panel evidence from China. Transp. Policy 2020, 90, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalayen, Q. The Strategic Role of Australian Regional Ports in Regional Development. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Burskyte, V.; Belous, O.; Stasiskiene, Z. Sustainable development of deep-water port: The case of Lithuania. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2011, 18, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, J. Social Development: Theory and Practice; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program U.N.D.P. What Is Human Development. 2022. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/about/human-development (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Markota Vukić, N.; Omazić, M.A.; Pejic-Bach, M.; Aleksić, A.; Zoroja, J. Leadership for Sustainability: Connecting Corporate Responsibility Reporting and Strategy. In Research Anthology on Developing Socially Responsible Businesses; Information Resources Management Association, Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Styliadis, T.; Angelopoulos, J.; Leonardou, P.; Pallis, P. Promoting Sustainability through Assessment and Measurement of Port Externalities: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Paths. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Laxe, F.; Martin Bermúdez, F.; Martin Palmero, F. Good Practices in Strategic Port Performance. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2022, 11, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezcan, Ö.; Kuleyin, B. A New Perspective on Selecting Port Managers. In Handbook of Research on the Future of the Maritime Industry; Senbursa, N., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Felício, J.A.; Batista, M.; Dooms, M.; Caldeirinha, V. How do sustainable port practices influence local communities’ perceptions of ports? Marit. Econ. Logist. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentchev, N.A. Corporate social performance as a business strategy. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 55, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Katuwawala, H.C.; Bandara, Y.M. System-based barriers for seaports in contributing to Sustainable Development Goals. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Caldwell, M.R. Stakeholder perceptions of seaport resilience strategies: A case study of gulfport (Mississippi) and providence (Rhode Island). Coast. Manag. 2015, 43, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.P. A Positive Theory of Moral Management, Social Pressure, and Corporate Social Performance. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 7–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendtorff, J.D. The Concept of Business Legitimacy. In Responsibility and Governance; Crowther, D., Seifi, S., Wond, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Strapazzon, C.L.; Wandscheer, C.B. Brazilian Legal Time of Sustainable Development: A Short Term View in Contrast with Agenda 2030. In Universities and Sustainable Communities: Meeting the Goals of the Agenda 2030; Leal Filho, W., Tortato, U., Frankenberger, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.J. Measuring Corporate Social Performance: A Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 50–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Social Role | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Regional developer | Care about regional development and the impact created on stakeholders. | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| Consider the impact of the sustainability performance approach on the development of the region | [21,22] | |

| Spread benefits of its operational functions beyond the area close to the ports | [33,34,35,36] | |

| Promote a collaborative and innovative environment | [6,13,37,38,39,40] | |

| Transfer knowledge | [53] | |

| Overall regional development | [35,45,46,47,48,49,50] | |

| Mitigate negative social impacts | [51] | |

| Economic enabler | Socio-economic role related to job creation | [5,23,24,25,26,27,28] |

| Create wealth for the region | [41] | |

| Supply-chain connector | Serve as a connection point for regions around the globe | [13,29,30] |

| Strive to become an efficient functional organisation | [29,31,32] | |

| Contribute to different supply chains development | [42] | |

| Corporate citizenship | Contribute to different supply chains development | [42] |

| Adopt a leadership position concerning social development | [54,55,56] | |

| Develop managers to act in the social dimension | [9,56] | |

| Preserve the cultural heritage | [20,57,58] | |

| Support the security of the coastal region | [60,61,62,63] |

| ID | Region | Gender | Designation | Academic Background /Highest Level | Type of Cargo Handled | Port Ownership Nature | Experience (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tint_01 | S | male | Chief Executive Officer | Merchant Marine Academy/MBA | Container, grains | Private | 19 |

| Tint_02 | SE | male | Social Communication Coordinator | Business Administration/Master’s degree | General cargo | Public | 7 |

| Tint_03 | S | male | HSE and Sustainability Corporate Manager | Mechanical Engineer/Business specialisation | Container, general cargo | Private | 11 |

| Tint_04 | S | male | Safety Health Environment Manager | Environmental and Sanitary Engineer/Business specialisation | General cargo/container/bulk | Public | 6 |

| Tint_05 | S | male | Institutional and Environmental Management | Business Administration/Master’s degree | General cargo/container/bulk | Private | 17 |

| Tint_06 | SE | male | Institutional Relations Manager | Business Administration/Business specialisation | Solid bulk | Private | 11 |

| Tint_07 | SE | female | Social Responsibility and Licensing Manager | Chemical Engineer/Master’s degree | Solid bulk | Private | 10 |

| Tint_08 | NE | female | Chief Compliance Officer | Degree in Education/PhD | General cargo/container/bulk | Public | 4 |

| Tint_09 | N | male | Safety Health Environment Manager | Forest Engineer/Master’s degree | Solid bulk | Private | 23 |

| Tint_10 | NE | male | Port Executive Manager | Metallurgical Engineering/MBA | Solid bulk | Private | 19 |

| Tint_11 | SE | male | Sustainability and Legal Director | Law degree/Business specialisation | General cargo/bulk/support | Private | 1 |

| Tint_12 | SE | male | Corporate Communications Coordinator | Degree in Journalism/MBA | Container, general cargo | Private | 6 |

| Tint_13 | SE | female | Port Superintendent Director | Business Administration/MBA | Solid bulk | Private | 14 |

| Tint_14 | SE | male | Human Rights Manager | Economy Degree/Masters | Solid bulk | Private | 9 |

| Tint_15 | SE | male | Social responsibility and Institutional Relations Manager | Degree in Law/MBE | General cargo/bulk/support | Private | 5 |

| Tint_16 | SE | male | Health and Safety, Environmental and Quality Manager | Degree in Oceanography/Master’s degree | Liquid bulk | Private | 10 |

| Tint_17 | N | male | Operations General Manager (Port) | Metallurgical Engineering/Business specialisation | Solid bulk | Private | 1 |

| Tint_18 | SE | male | Port Operations Manager | Industrial Engineer/MBA | Solid bulk, liquid bulk | Private | 12 |

| Tint_19 | SE | male | CEO and COO | Metallurgical Engineering/Master’s degree | Solid bulk | Private | 12 |

| Tint_20 | N | male | Sustainability and Institutional Relations Manager | Business Administration/MBA | Solid bulk | Private | 36 |

| Tint_21 | N | male | Sustainability Manager | Business Administration/Business specialisation | Solid bulk | Private | 3 |

| Tint_22 | N | female | Communication and Community Relations Coordinator | Business Administration/MBA | Solid bulk | Private | 5 |

| Tint_23 | N | male | Sustainability Manager | Civil Engineering Degree/PhD | Solid bulk | Private | 8 |

| Tint_24 | SE | male | Port Operations Manager | Mechanical Engineer/Business specialisation | Solid bulk | Private | 30 |

| Tint_25 | N | male | Port general Manager | Business Administration/Master’s degree | Liquid bulk | Private | 5 |

| Tint_26 | N | male | Logistics General Manager | Mechanical Engineer/MBA | Solid bulk | Private | 10 |

| Tint_27 | NE | female | Social Responsibility Analyst | Degree in Social Service/MBA | Energy production | Private | 6 |

| Tint_28 | NE | male | Environment and Safety General Manager | Environmental Control Technology/Business specialisation | Solid bulk | Private | 11 |

| ID | Theme Description | Coding | Participants’ References (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SR.1 | Develop the regional social environment | To leverage the regional development To support the development of the region To leverage the regional development To connect with its region to generate value To act as the vector of regional development To develop the strong points of the region To contribute to the social development To take care of the region where the port is To create shared value | 9 |

| SR.2 | Adapt ports’ processes to achieve social objectives | To have experts in the social area To operate in a sustainable way To match investments with the real demand in the social area To grow sustainably To act proactively in managing external and internal stakeholders To act with respect and proactivity To understands the impacts caused by its operations To respond to demands arising from its operations | 8 |

| SR.3 | Improve the economic status of the region | To generate income and wealth To generate income for those involved in the port activity To create indirect jobs To generate wealth for the region where it is installed | 4 |

| SR.4 | Act as a leader in the social dimension | To act as a society leader To connect companies and actions in the social area To lead by example | 3 |

| SR.5 | Maximise port’s economic capabilities to provide social betterment | To act as an efficient and safe supply chain link To act as an efficient hub in the region where it operates To generate benefits for stakeholders based on cargo flow efficiency | 3 |

| ID | Theme | Coding | Participants Reference (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M.1 | Social accountability | Because it is not acceptable to refuse social participation Because ports are part of people’s lives Because ports have great strategic importance and influence power Because ports impact societies, change their behaviour and must minimise impacts Because the port is essential in the supply chain development Because this should be part of the natural behaviour of the company | 22 |

| M.2 | Stakeholders’ support | Because it is necessary to have society on your side in difficult moments Because the port needs the social license | 6 |

| M.3 | Strategic development | Because it improves the port image and reputation Because it promotes higher engagement from employees Because this is necessary for survival Because there is a trend for more demand for social performance | 5 |

| M.4 | Prevention of problems escalation | Because external factors can become a problem Because society complaints can turn into more significant problems Because there is a risk that social problems escalate to something bigger | 4 |

| M.5 | Compliance with laws and regulations | Because there is law enforcement in place | 2 |

| M.6 | Return for the exploitation of resources | Because the company needs to return to society the profit from the exploration of natural resources Because the wealth must be shared | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batalha, E.; Chen, S.-L.; Pateman, H.; Zhang, W. Defining a Social Role for Ports: Managers’ Perspectives on Whats and Whys. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032646

Batalha E, Chen S-L, Pateman H, Zhang W. Defining a Social Role for Ports: Managers’ Perspectives on Whats and Whys. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032646

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatalha, Eduardo, Shu-Ling Chen, Hilary Pateman, and Wei Zhang. 2023. "Defining a Social Role for Ports: Managers’ Perspectives on Whats and Whys" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032646

APA StyleBatalha, E., Chen, S.-L., Pateman, H., & Zhang, W. (2023). Defining a Social Role for Ports: Managers’ Perspectives on Whats and Whys. Sustainability, 15(3), 2646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032646