Entrepreneurship at the Bottom of the Pyramid: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

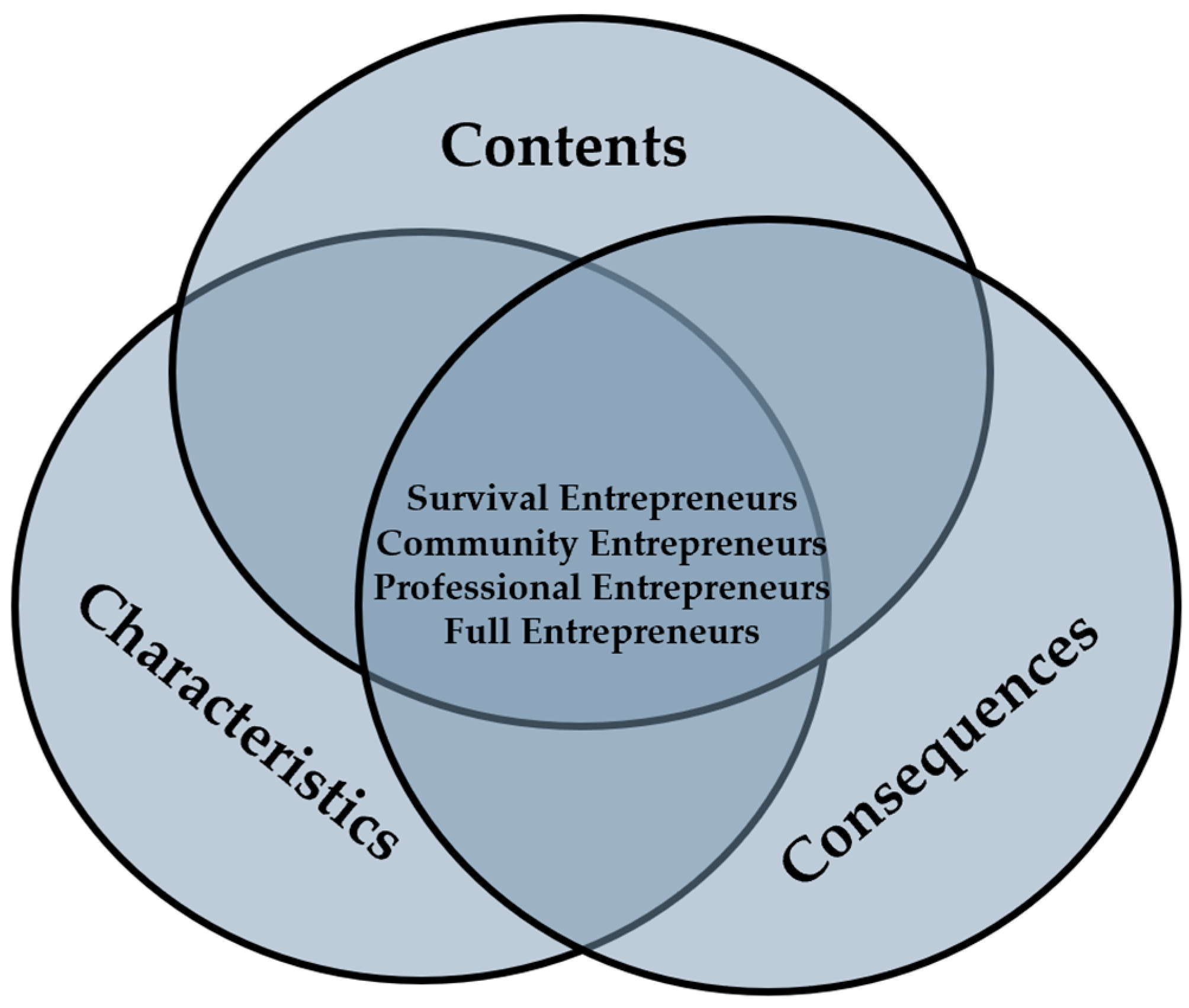

- What are the characteristics of local entrepreneurs at the BoP (characteristics)?

- What are the contents of entrepreneurial activities at the BoP (contents)?

- What are the consequences of entrepreneurial activities at the BoP (consequences)?

2. Evolvement of the Concept of BoP

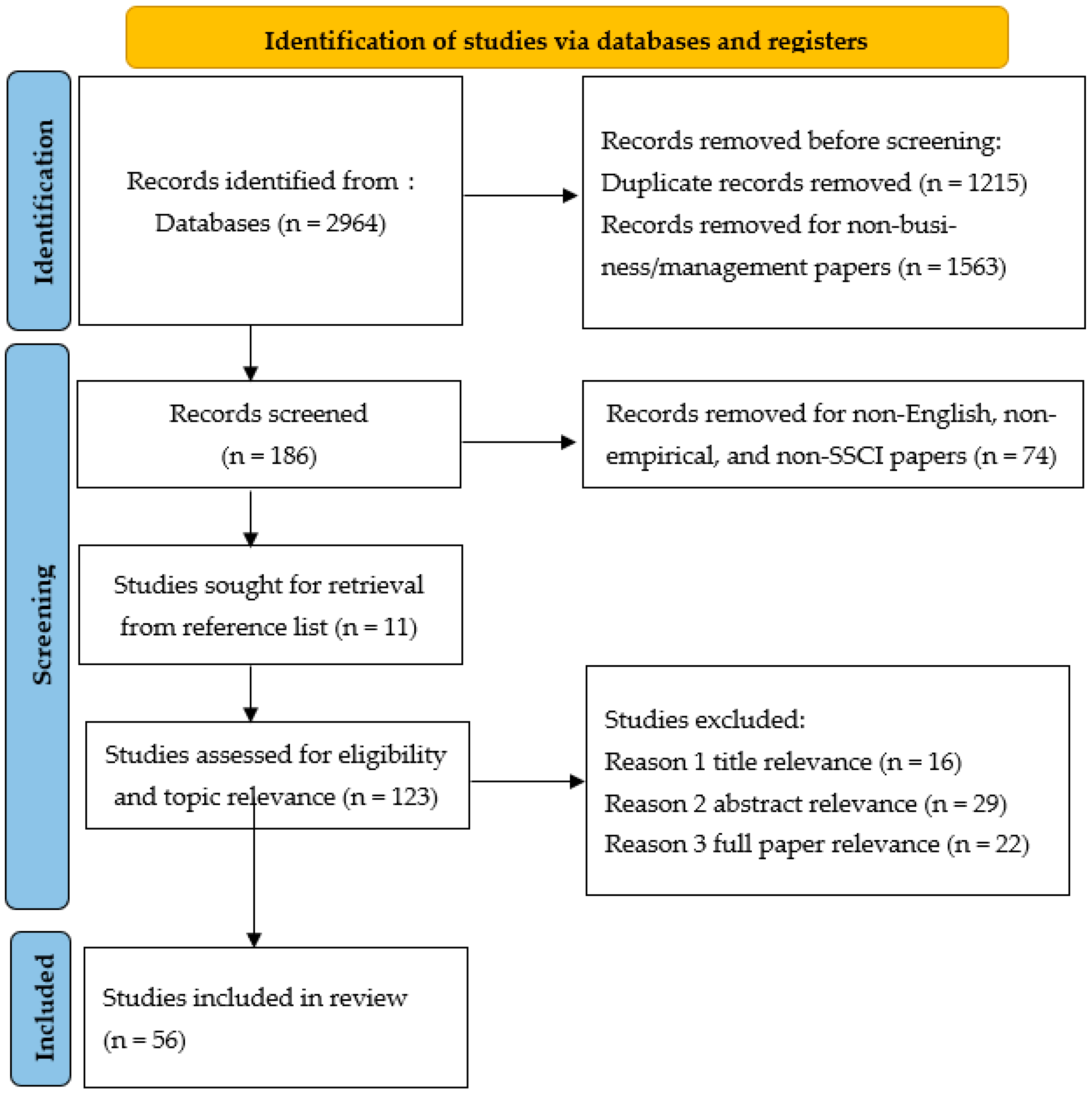

3. Methodology

- Stage 1: Planning the review

- Stage 2: Conducting the review

- Stage 3: Descriptive analysis and reporting

4. Findings

4.1. Research Question 1: Characteristics of BoP Entrepreneurship

4.1.1. Individual Characteristics

4.1.2. Business Characteristics

4.2. Research Question 2: Content of BoP Business

4.2.1. Food-Related Business

4.2.2. Manufactured Product Sales

4.2.3. Self-Made Product Sales

4.2.4. Services

4.2.5. Manufacturing

4.3. Research Question 3: Consequences of BoP Businesses

4.3.1. Personal Growth

4.3.2. Formalization of Businesses

4.3.3. Poverty Alleviation

5. Discussion

5.1. Types of Entrepreneurs

5.1.1. Survival Entrepreneurs

5.1.2. Community Entrepreneurs

5.1.3. Professional Entrepreneurs

5.1.4. Full Entrepreneurs

5.2. Emerging Topics for Four Types of Entrepreneurs

5.2.1. Survival Entrepreneurs

5.2.2. Community Entrepreneurs

5.2.3. Profession Entrepreneurs

5.2.4. Full Entrepreneurs

5.3. Implications and Limits of Findings

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- London, T.; Esper, H.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Kistruck, G. Connecting Poverty to Purchase in Informal Markets. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2014, 8, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hart, S.L. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Available online: https://www.strategy-business.com/article/11518 (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. The Economic Lives of the Poor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembek, K.; Sivasubramaniam, N.; Chmielewski, D. A Systematic Review of the Bottom/Base of the Pyramid Literature: Cumulative Evidence and Future Directions. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, S.; Vann, R.; Camacho, S.; Baker, C.; Leary, R.; Mittelstaedt, J.; Rosa, J. Subsistence Consumer-Merchant Marketplace Deviance in Marketing Systems: Antecedents, Implications, and Recommendations. J. Macromark. 2014, 34, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J. Profitable Business Models and Market Creation in the Context of Deep Poverty: A Strategic View. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivarajan, S.; Srinivasan, A. The Poor as Suppliers of Intellectual Property: A Social Network Approach to Sustainable Poverty Alleviation. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Si, S. Poverty Reduction through Entrepreneurship: Incentives, Social Networks, and Sustainability|SpringerLink. Asian Bus. Manag. 2018, 17, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G.; Bjørnskov, C. The Context of Entrepreneurial Judgment: Organizations, Markets, and Institutions. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 1197–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, A. Failure of the Libertarian Approach to Reducing Poverty. Asian Bus. Manag. 2010, 9, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, T.; Anupindi, R.; Sheth, S. Creating Mutual Value: Lessons Learned from Ventures Serving Base of the Pyramid Producers. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.; Chakrabarti, R.; Singh, R. Markets and Marketing at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Mark. Theory 2017, 17, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdakul, D.; Atik, D.; Dholakia, N. Redefining the Bottom of the Pyramid from a Marketing Perspective. Mark. Theory 2017, 17, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, S.; Maltz, E.; Viswanathan, M.; Gupta, S. Transformative Subsistence Entrepreneurship: A Study in India. J. Macromark. 2014, 34, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korosteleva, J.; Stępień-Baig, P. Climbing the Poverty Ladder: The Role of Entrepreneurship and Gender in Alleviating Poverty in Transition Economies. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Sridharan, S.; Ritchie, R.; Venugopal, S.; Jung, K. Marketing Interactions in Subsistence Marketplaces: A Bottom-Up Approach to Designing Public Policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2012, 31, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner, B.E.; Payne, D. Evolution and Implementation: A Study of Values, Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 41, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashitew, A.; Narayan, S.; Rosca, E.; Bals, L. Creating Social Value for the “Base of the Pyramid”: An Integrative Review and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumra, R.; Singh, R. Drivers, Barriers, and Facilitators of Entrepreneurship at BoP: Review, Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. J. Macromark. 2022, 42, 381–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumra, R.; Singh, R. Base of the Pyramid Producers’ Constraints: An Integrated Review and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Rivera-Santos, M.; Rufin, C. Reviewing a Decade of Research on the “Base/Bottom of the Pyramid” (BOP) Concept. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 338–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, S.; Khan, N.A.; Belal, A.R. Corporate Community Involvement In Bangladesh: An Empirical Study: Corporate Community Involvement In Bangladesh: An Empirical Study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrozo, E. Proposition of BoP 3.0 as an Alternative Model of Business for BoP (Base of Pyramid) Producers: Case Study in Amazonia. In The Challenges of Management in Turbulent Times: Global Issues from Local Perspective; Universid de Occidente: Escuintla, Mexico, 2015; Volume 189, pp. 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Simanis, E.; Hart, S. The Base of the Pyramid Protocol; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, C. The Nestlé Infant Formula Controversy and a Strange Web of Subsequent Business Scandals. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, N. A Critical Discourse Analysis to Explain the Failure of BoP Strategies. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2021, 17, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahi, T. Cocreation at the Base of the Pyramid: Reviewing and Organizing the Diverse Conceptualizations. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 416–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanis, E.; Duke, D. Profits at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, K. Ethical Concerns at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Where CSR Meets BOP. J. Int. Bus. Ethics 2009, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dembek, K.; Sivasubramaniam, N. Examining Base of the Pyramid (BoP) Venture Success through the Mutual Value CARD Approach. Oxf. Handb. Manag. Emerg. Mark. 2019, 240–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Rosa, J.; Ruth, J. Exchanges in Marketing Systems: The Case of Subsistence Consumer-Merchants in Chennai, India. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekambi, S.; Ingenbleek, P.; van Trijp, H. Integrating Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Producers with High-Income Markets: Designing Institutional Arrangements for West African Shea Nut Butter Producers. J. Public Policy Mark. 2018, 37, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, R.; Qureshi, I.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Jaikumar, S. Digitally Mediated Value Creation for Non-Commodity Base of the Pyramid Producers. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoso, J.; Cabrera, K. Managing Informal Service Organizations at the Base of the Pyramid (BoP). J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Santos, S.; Neumeyer, X. Entrepreneurship as a Solution to Poverty in Developed Economies. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; McLean, M. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review of the Concept. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Warren, L. The Entrepreneur as Hero and Jester: Enacting the Entrepreneurial Discourse. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creevey, D.; Coughlan, J.; O’Connor, C. Social Media and Luxury: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xheneti, M.; Madden, A.; Thapa Karki, S. Value of Formalization for Women Entrepreneurs in Developing Contexts: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchart, E.; Gruber, M. Darwinians, Communitarians, and Missionaries: The Role of Founder Identity in Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, D.L.; Michailova, S. Cultural Intelligence: A Review and New Research Avenues. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. Learning from Research: Systematic Reviews for Informing Policy Decisions; A Paper for the Alliance for Useful Evidence; Nesta: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Azmat, F.; Samaratunge, R. Exploring Customer Loyalty at Bottom of the Pyramid in South Asia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2013, 9, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKague, K.; Oliver, C. Enhanced Market Practices: Poverty Alleviation for Poor Producers in Developing Countries. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2012, 55, 98–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. Grassroots Entrepreneurs and Social Change at the Bottom of the Pyramid: The Role of Bricolage. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 30, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierenga, M. Uncovering the Scaling of Innovations Developed by Grassroots Entrepreneurs in Low-Income Settings. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, S.V.; SadreGhazi, S.; Duysters, G. On the Diffusion of Toilets as Bottom of the Pyramid Innovation: Lessons from Sanitation Entrepreneurs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, G.; Aman, A. Women Entrepreneurs: How Power Operates in Bottom of the Pyramid-Marketing Discourse. Mark. Theory 2017, 17, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S. The Business Model Canvas of Women Owned Micro Enterprises in the Urban Informal Sector. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, S.; Viswanathan, M.; Jung, K. Consumption Constraints and Entrepreneurial Intentions in Subsistence Marketplaces. J. Public Policy Mark. 2015, 34, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Shahid, M.S. Informal Entrepreneurship and Institutional Theory: Explaining the Varying Degrees of (in)Formalization of Entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016, 28, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Amran, A.; Ahmad, N.; Taghizadeh, S. Supporting Entrepreneurial Business Success at the Base of Pyramid through Entrepreneurial Competencies. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 1203–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Sergi, B.; Jaiswal, M. Understanding the Challenges and Strategic Actions of Social Entrepreneurship at Base of the Pyramid. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 418–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Praetorius, T.; Narayanamurthy, G.; Hasle, P.; Pereira, V. Finding Your Feet in Constrained Markets: How Bottom of Pyramid Social Enterprises Adjust to Scale-up-Technology-Enabled Healthcare Delivery. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, J.; Pant, A.; Pani, S. Building the BoP Producer Ecosystem: The Evolving Engagement of Fabindia with Indian Handloom Artisans. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, D.; Nilakantan, R.; Rao, S. On Entrepreneurial Resilience among Micro-Entrepreneurs in the Face of Economic Disruptions Horizontal Ellipsis A Little Help from Friends. J. Bus. Logist. 2021, 42, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson-Lartego, L.; Mathiassen, L. Microfranchising to Alleviate Poverty: An Innovation Network Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Echambadi, R.; Venugopal, S.; Sridharan, S. Subsistence Entrepreneurship, Value Creation, and Community Exchange Systems: A Social Capital Explanation. J. Macromark. 2014, 34, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Bakshi, M.; Mishra, P. Corporate Social Responsibility: Linking Bottom of the Pyramid to Market Development? J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. A Suitable Woman: The Coming-of-Age of the “third World Woman” at the Bottom of the Pyramid: A Critical Engagement. Hum. Relat. 2020, 73, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musona, J.; Sjögrén, H.; Puumalainen, K.; Syrjä, P. Bricolage in Environmental Entrepreneurship: How Environmental Innovators “Make Do” at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, L.; Muthuri, J.N. Engaging Fringe Stakeholders in Business and Society Research: Applying Visual Participatory Research Methods. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 131–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounhouigan, M.H.; Ingenbleek, P.T.M.; van der Lans, I.A.; van Trijp, H.C.M.; Linnemann, A.R. The Adaptability of Marketing Systems to Interventions in Developing Countries: Evidence from the Pineapple System in Benin. J. Public Policy Mark. 2014, 33, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilahiane, H. Catenating the Local and the Global in Morocco: How Mobile Phone Users Have Become Producers and Not Consumers. J. N. Afr. Stud. 2013, 18, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantz, A.; Kistruck, G.; Zietsma, C. The Opportunity Not Taken: The Occupational Identity of Entrepreneurs in Contexts of Poverty. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 416–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yessoufou, A.W.; Blok, V.; Omta, S.W.F. The Process of Entrepreneurial Action at the Base of the Pyramid in Developing Countries: A Case of Vegetable Farmers in Benin. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 30, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabisi, J.; Kwesiga, E.; Juma, N.; Tang, Z. Stakeholder Transformation Process: The Journey of an Indigenous Community. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, C.; Rajak, D. Remaking Africa’s Informal Economies: Youth, Entrepreneurship and the Promise of Inclusion at the Bottom of the Pyramid: The Journal of Development Studies: Vol 52, No 4. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavee-Geo, R.; Burki, U.; Buvik, A. Building Trustworthy Relationships with Smallholder(Small-Scale) Agro-Commodity Suppliers: Insights from the Ghana Cocoa Industry. J. Macromark. 2020, 40, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekambi, S.; Ingenbleek, P.; van Trijp, H. Integrating Producers at the Base of the Pyramid with Global Markets: A Market Learning Approach. J. Int. Mark. 2015, 23, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, C.; Roll, K. ASR FORUM: ENGAGING WITH AFRICAN INFORMAL ECONOMIES: Capital’s New Frontier: From “Unusable” Economies to Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Markets in Africa. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2013, 56, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Ramírez, L.; Toledo-López, A. Strategic Orientation in Handicraft Subsistence Businesses in Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 476–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.; Hall, J. An Exploratory Study of Entrepreneurs in Impoverished Communities: When Institutional Factors and Individual Characteristics Result in Non-Productive Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, A.; Blocker, C.P. The Contextual Value of Social Capital for Subsistence Entrepreneur Mobility. J. Public Policy Mark. 2015, 34, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Mason, K.; Chakrabarti, R. Managing to Make Market Agencements: The Temporally Bound Elements of Stigma in Favelas. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Matos, S.; Sheehan, L.; Silvestre, B. Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the Base of the Pyramid: A Recipe for Inclusive Growth or Social Exclusion? J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Lopez, A.; Diaz-Pichardo, R.; Jimenez-Castaneda, J.; Sanchez-Medina, P. Defining Success in Subsistence Businesses. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1658–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Webb, J.; Kistruck, G.; Ketchen, D.J.; Ireland, R.D. Transitioning Entrepreneurs from Informal to Formal Markets. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 420–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Kuratko, D.F.; Audretsch, D.B.; Santos, S. Overcoming the Liability of Poorness: Disadvantage, Fragility, and the Poverty Entrepreneur. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, E.; Gomez, G.; Knorringa, P. ‘Helping a Large Number of People Become a Little Less Poor’: The Logic of Survival Entrepreneurs. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2012, 24, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Agarwal, N.; Brem, A. Women Entrepreneurs as Agents of Change: A Comparative Analysis of Social Entrepreneurship Processes in Emerging Markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 157, 120067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacroix, E.; Parguel, B.; Benoit-Moreau, F. Digital Subsistence Entrepreneurs on Facebook. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.; Tang, C. Supply Chain Opportunities at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Decision 2016, 43, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Hahn, R.; Seuring, S. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in “Base of the Pyramid” Food Projects—A Path to Triple Bottom Line Approaches for Multinationals? Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, N.; Olabisi, J.; Griffin-EL, E. Understanding the Motivation Complexity of Grassroots Ecopreneurs at the Base of the Pyramid. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, S.; Viswanathan, M. Negotiated Agency in the Face of Consumption Constraints: A Study of Women Entrepreneurs in Subsistence Contexts. J. Public Policy Mark. 2020, 40, 074391562095382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Poor Markets: Perspectives from the Base of the Pyramid. Decision 2015, 42, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Fressoli, M.; Thomas, H. Grassroots Innovation Movements: Challenges and Contributions. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, S.; Mukherjee, V. Can Breakthrough Innovations Serve the Poor (Bop) and Create Reputational (CSR) Value? Indian Case Studies. Technovation 2014, 34, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Cazares, R.; Lawson-Lartego, L.; Mathiassen, L.; Quinonez-Romandia, S. Strategizing for the Bottom of the Pyramid: An Action Research into a Mexican Agribusiness. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020, 35, 1475–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z. How Is Entrepreneurship Good for Economic Growth? Innovation 2006, 1, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.M.; Fernandes, C.I.; Kraus, S. Entrepreneurship Research: Mapping Intellectual Structures and Research Trends. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Wood, G. A Model of Business Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Unni, J. Women Entrepreneurship: Research Review and Future Directions. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2016, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munton, S.C.; Ozkazanc-Pan, B. Feminist Perspectives on Social Entrepreneurship: Critique and New Directions. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2016, 8, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Geographical Spread of Studies | Author(s) and Publication Year |

|---|---|

| Asia | [7,10,14,16,31,33,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] |

| Africa | [32,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73] |

| Central & South America | [5,34,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] |

| Mixed places or others | [3,11,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

| Category | Coding Results | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | Social status | Under USD 2/day; lack of a safety net; scarcity of poorness; low income; part of self-help group (SHG) network; involuntary entrepreneurs; from lower social class; struggle to survive; multiple occupations; a business and a laborer’s job; self-employment; motivated by survival needs and few possibilities for upward mobility |

| Gender | Female majority; urban poor women; member of a women’s SHG affiliated with a non-profit organization; women in the majority | |

| Education | Low literacy; literacy gaps; non-literate; low level of education; lesser knowledge, information, and skills base; low-to-moderately-literate population; low formal education; illiteracy | |

| Capabilities | Extremely poor and weak; resource-poor; lack efficient means of communication; limited access to complementary infrastructure; lack the skills, vision, creativity, and drive of an entrepreneur; financial constraints; no specialized skills; acute resource constraints; digital | |

| Psychological factors | Myopic/alert; lack of a safety net; intense non-business pressures; resource scarcity | |

| Beliefs | Survivalist; collectivism; fatalism; little or no social responsibility concerns | |

| Business characteristics | Legitimacy | Not registered; do not pay any taxes; obligation to share a high perceived level of public sector corruption; not subject to any taxes or even minimum-wage restrictions; tax rates perceived as too high; low tax morality; high resistance against the state; do not perceive it risky to run an unregistered business |

| Nature | Rural areas; rural areas with scant infrastructure; embeddedness in social relations; ease of entry; street businesses; self-employed in agriculture; low capital, skills, and technology requirements; part of a diversification strategy, often run by idle labor, with interruptions, and/or part-time; sole-owned; no brand capital; low public visibility; raise capital; too small a scale; no paid staff; few assets; low entry barriers; too much competition; low productivity | |

| Operations | Consumer–merchant; owns some land; the residual claimants of earnings; meagre earnings that cannot lift their owners out of poverty |

| Category | Specific BoP Business | Entrepreneurial Initiative | Managerial Skill Requirement | Resource Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foods | Natural Agri-foods drinking water; shea nut butter; chicken; fruits; vegetables; flowers; fish; pooja items (e.g., coconuts); coffee; plants; avocados; milk; raw lemons; vegetable wholesaler; shrimp; shea butter; mango; dairy; cocoa; shea oil; maize; okra; rice; beans | BoP entrepreneurs identify the market needs for natural food products | None | Low |

| Food Stand tea and tiffin (light meal); snack; bread snacks; sweet peanuts; readymade food; provision shop; small snack shop; small eatery; tea and food; homemade pickle; dawadawa cake; appalam (snack); idli (food); porridge; restaurateurs; forestry | BoP entrepreneurs provide food-related products made by themselves to make a living | |||

| Product sale | Manufactured goods wedding cards; pillow, table and sofa cover; jewelry; perfume; leather bags; reading glasses; wearable accessories; foam puppets; female clothes; decorative rugs; propane gas; purses; candies; umbrellas; small vessels; pajamas; sunglasses; utensils; Coca-Cola; eyeglasses; chess classes; world cup merchandise; cleaning powder; saree; costume; toys; fabric; sanitation; pharmaceutical products; second-hand clothes; children’s items; embroidered items; pottery; textiles; Unilever’s consumer packaged goods | BoP entrepreneurs accommodate their products to local demand and flexibly adjust their selling strategies to various buyers | Medium | Low |

| Handcrafted items wood carving and metalwork; traditional outfits; Pattachitro painting on umbrella; beer mug; painting on jute bag; earrings made of fabric cloth; handmade jute pouch bags; hand embroidery on cushion cover; wood handicraft; display board; hand-sewn goods; handmade party decorations; worship items | BoP entrepreneurs may create or improve their self-made products to adapt to the market needs and explore new markets enabled by digital platforms | Relatively high | Medium | |

| Service | Labor service helper in ration shop; small repair shops; tour operator; fishing guide; “kirana” (grocery) shop; neighborhood small store owner; balloon shooting on beach; SHG member; scrap dealer; tailor; seamstress; plumbers; carpenters; electricians; fishermen; porter; mining; goldsmith; construction; contract gardener; colored cotton co-op; cotton farmers in cooperative; tile laying masters; skilled construction workers; locksmith; maids; hairdresser; plumbing; laundry; handloom | BoP entrepreneurs provide services with the intention to operate the business with the minimum capital input and absorb the knowledge, information, and skills outside BoP | None | Low |

| Professional services Art-related: arts and crafts producers and sale; painter; artisan; craft worker; music producer; DJ; photographer Healthcare: primary care; health clinics Finance: financier; petty shop; diwali fund operator; chit fund operator; pawn broker ICT: community information centers; telecom-related services (cybercafe; telephone cabins); telephone booths; computer center Transport: taxi(tuk-tuk) driver; daily flower delivery; vegetable transportation; milk delivery | High | Medium | ||

| Manufacturing | sanitary napkin machine; affordable and no electricity cooling machine; reversible reduction gearbox; manufacturing shoes, toys, and local savory items; clay pot manufacturer | BoP entrepreneurs leverage the capital they can access and cooperate with economic and social stakeholders to start a formal business | Very high | High |

| Type | Characteristics | Content (Business Sector) | Consequences | Emerging Topics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival entrepreneur | Survival mindset Self-sufficiency | Natural foods Manufactured goods Labor service | Remain as micro-business | Ethical issues Psychological drivers |

| Community entrepreneur | Business alertness and identity Local needs exploration Local resource exploitation | Food stand Manufactured goods Handcrafted items Profession service | Informal businesses within communities | Female entrepreneurs |

| Professional entrepreneur | External knowledge and skill dependent Knowledge and skill entrepreneurship | Art-related goods/service Professional service | Establish formal business | Migrant worker |

| Full entrepreneur | Risk-taking Resource integration and configuration Stakeholder seeking and management | Manufacturing. | Large-scale businesses Emerging industries | Stakeholder management Resource configuration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y. Entrepreneurship at the Bottom of the Pyramid: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032480

Yu K, Zhang Y, Huang Y. Entrepreneurship at the Bottom of the Pyramid: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032480

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Kaidong, Yameng Zhang, and Yicong Huang. 2023. "Entrepreneurship at the Bottom of the Pyramid: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032480

APA StyleYu, K., Zhang, Y., & Huang, Y. (2023). Entrepreneurship at the Bottom of the Pyramid: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 15(3), 2480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032480