Buying Behaviour towards Eco-Labelled Food Products: Mediation Moderation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

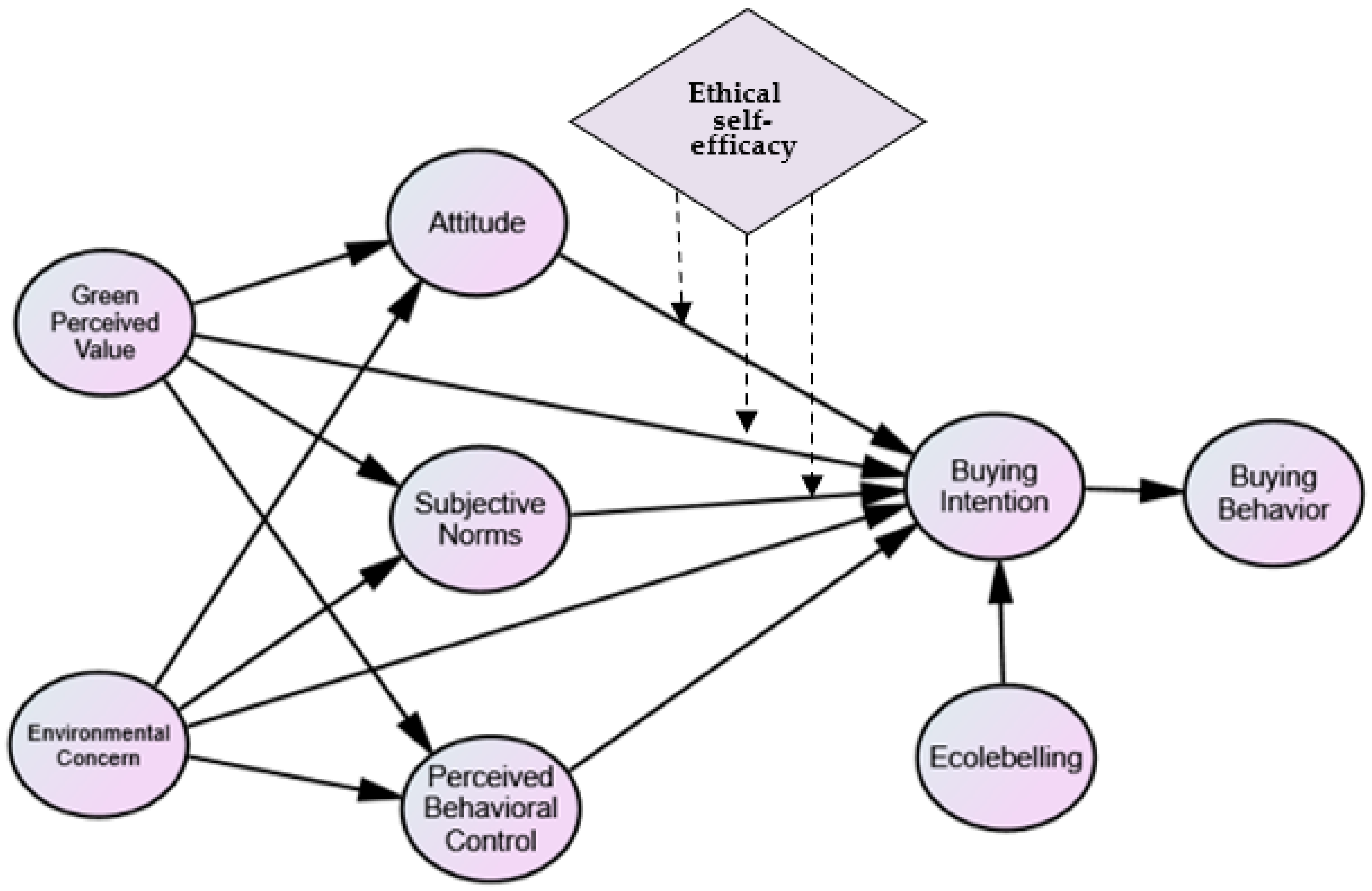

2. Underpinning Theories

2.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

2.2. Need for Extension TPB

3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Green Perceived Value

3.2. Environmental Concern

3.3. Effect of TPB Constructs on Buying Intention and Actual Behaviour

3.4. Eco-Labelling

3.5. Behavioural Intention

3.6. Mediating Effect of TPB

3.7. Moderating Role of Ethical Self-Efficacy

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample and Method

4.2. Measures

4.3. Common Method Bias

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Measurement Model (Reliability and Validity)

5.2. Testing Normality and Multicollinearity

5.3. Coefficient of Determination

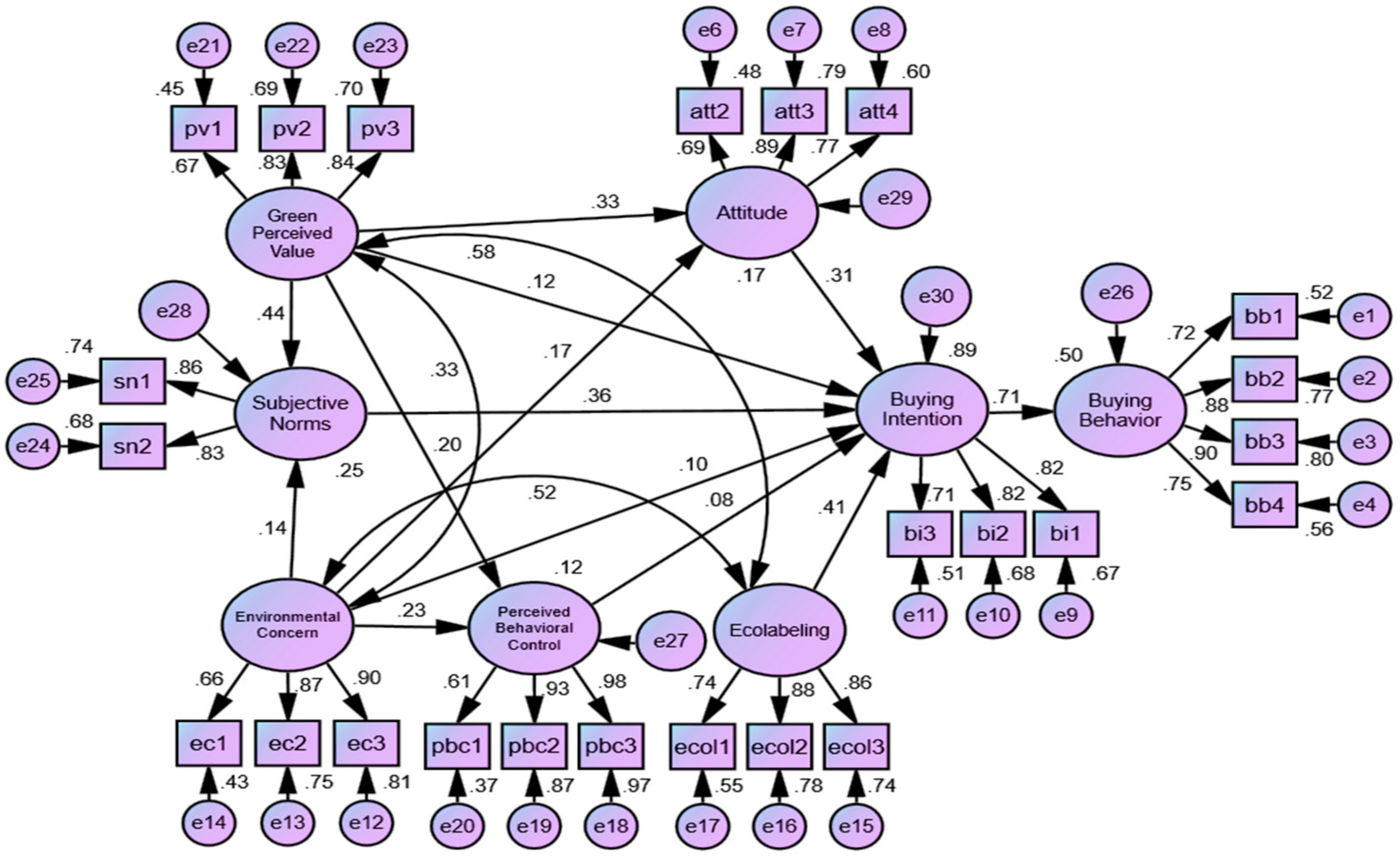

5.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.5. Structural Modelling

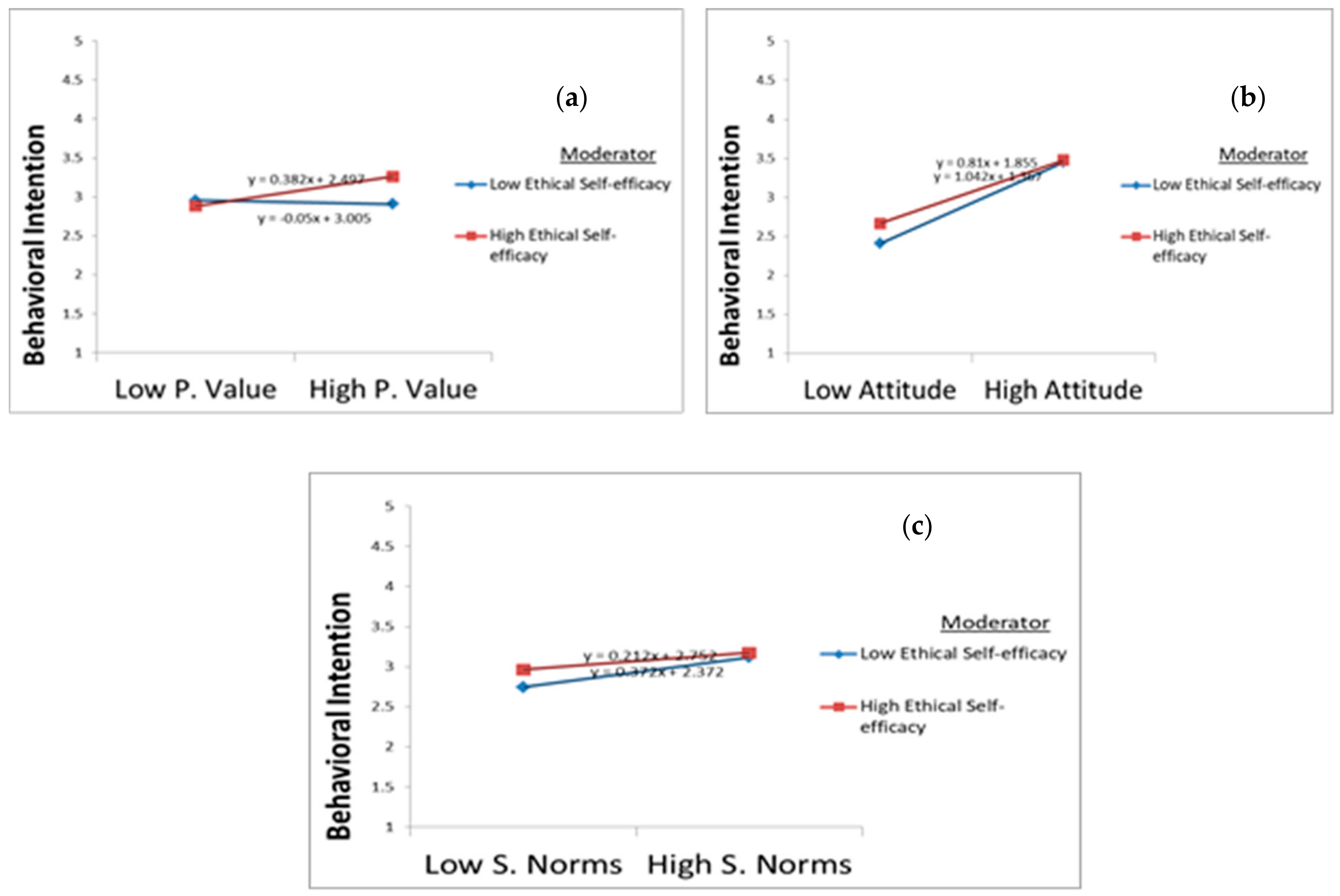

5.6. Mediation and Moderation Effect of TPB Constructs

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Implications

8.1. Managerial Implication

8.2. Policy Implications

8.3. Theoretical Contribution

9. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fransson, N.; Gärling, T. Environmental Concern: Conceptual Definitions, Measurement Methods, and Research Findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleda, M.; Valente, M. Graded Eco-Labels: A Demand-Oriented Approach to Reduce Pollution. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2009, 76, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.M. Factors That Influence Green Purchase Behaviour of Malaysian Consumers. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sammer, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. The Influence of Eco-labelling on Consumer Behaviour–Results of a Discrete Choice Analysis for Washing Machines. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2006, 15, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaysia Green Tech MyHijau Mark Directory. Available online: https://www.mgtc.my/our-services/myhijau-mark-directory/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Predict Consumers’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Exploring the Interaction Effects of Norms and Attitudes on Green Travel Intention: An Empirical Study in Eastern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Qin, H.; Wang, S. Young People’s Behaviour Intentions towards Reducing PM2. 5 in China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Mohamad, M.R.; Yaacob, M.R.B.; Mohiuddin, M. Intention and Behavior towards Green Consumption among Low-Income Households. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 227, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting Green Product Consumption Using Theory of Planned Behavior and Reasoned Action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grankvist, G.; Biel, A. Predictors of Purchase of Eco-Labelled Food Products: A Panel Study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Kast, S.W. Promoting Sustainable Consumption: Determinants of Green Purchases by Swiss Consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Leveraging Factors for Sustained Green Consumption Behavior Based on Consumption Value Perceptions: Testing the Structural Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 95, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A.; Rahman, S.U.; Salo, J. Antecedents of Green Behavioral Intentions: A Cross-country Study of T Urkey, F Inland and P Akistan. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daria, B.; Sara, K.S. The Influence of Eco-Labelled Products on Consumer Buying Behaviour-By Focusing on Eco-Labelled Bread. Ph.D. Thesis, Mälardalen University College, Västerås, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blend, J.R.; Van Ravenswaay, E.O. Measuring Consumer Demand for Ecolabeled Apples. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1999, 81, 1072–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarimoglu, E.; Gunay, T. The Extended Theory of Planned Behavior in Turkish Customers’ Intentions to Visit Green Hotels. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Ardekani, F.Z.; Pino, G.; Maleksaeidi, H. An Extended Model of Theory of Planned Behavior to Investigate Highly-Educated Iranian Consumers’ Intentions towards Consuming Genetically Modified Foods. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Explain the Effects of Cognitive Factors across Different Kinds of Green Products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, J.; Sun, A.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D. Residents’ Green Purchasing Intentions in a Developing-Country Context: Integrating PLS-SEM and MGA Methods. Sustainability 2020, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Consumers’ Intentions to Visit Green Hotels in the Chinese Context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2810–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting Green Hotel Behavioral Intentions Using a Theory of Environmental Commitment and Sacrifice for the Environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Perumal, S.; Ahmad, N. The Antecedents of Green Car Purchase Intention among Malaysian Consumers. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2019, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Harris, J.; Patterson, P.G. Customer Choice of Self-service Technology: The Roles of Situational Influences and Past Experience. J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An Investigation of Green Hotel Customers’ Decision Formation: Developing an Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting Consumers Who Are Willing to Pay More for Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Gender Differences in Egyptian Consumers’ Green Purchase Behaviour: The Effects of Environmental Knowledge, Concern and Attitude. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief; Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Application of the Extended VBN Theory to Understand Consumers’ Decisions about Green Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, L.; Huang, Y.K.; Hu, L. Green Attributes of Restaurants: What Really Matters to Consumers? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-C.; Lin, T.-H.; Lai, M.-C.; Lin, T.-L. Environmental Consciousness and Green Customer Behavior: An Examination of Motivation Crowding Effect. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courneya, K.S.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Arthur, K.; Bobick, T.M. Understanding Exercise Motivation in Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Prospective Study Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Rehabil. Psychol. 1999, 44, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior, 6th ed.; McGraw-hill Education: Milton Keynes, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Altawallbeh, M.; Soon, F.; Thiam, W.; Alshourah, S. Mediating Role of Attitude, Subjective Norm and Perceived Behavioural Control in the Relationships between Their Respective Salient Beliefs and Behavioural Intention to Adopt E-Learning among Instructors in Jordanian Universities. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, M.; Droms, C.M.; Craciun, G. The Impact of Attitudinal Ambivalence on Weight Loss Decisions: Consequences and Mitigating Factors. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.; David, P.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Self-efficacy or Perceived Behavioural Control: Which Influences Consumers’ Physical Activity and Healthful Eating Behaviour Maintenance? J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance Green Purchase Intentions: The Roles of Green Perceived Value, Green Perceived Risk, and Green Trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Spreng, R.A. Modelling the Relationship between Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions in a Business-to-Business, Services Context: An Empirical Examination. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doszhanov, A.; Ahmad, Z.A. Customers’intention To Use Green Products: The Impact Of Green Brand Dimensions And Green Perceived Value. In Proceedings of the SHS Web of Conferences, Kajang, SGR, Malaysia, 10 July 2015; Volume 5, p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, M.; Zuo, J.; Rameezdeen, R. Received vs. given: Willingness to Pay for Sponge City Program from a Perceived Value Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Jin, S.; Zhu, H.; Qi, X. Construction of Revised TPB Model of Customer Green Be-Havior: Environmental Protection Purpose and Ecological Values Perspectives. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Barcelona, Spain, 11–13 March 2018; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK; Volume 167, p. 12021. [Google Scholar]

- Salehzadeh, R.; Pool, J.K. Brand Attitude and Perceived Value and Purchase Intention toward Global Luxury Brands. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Zhang, Q. Green Purchase Intention: Effects of Electronic Service Quality and Customer Green Psychology. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X. Measuring Purchase Intention towards Green Power Certificate in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A Structural Equation Test of the Value-Attitude-Behavior Hierarchy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M. Investigating the Measurement of Consumer Ecological Behaviour, Environmental Knowledge, Healthy Food, and Healthy Way of Life. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 5, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green Purchasing Behaviour: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Investigation of Indian Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S.; Huang, D.-M. The Influence of Green Restaurant Decision Formation Using the VAB Model: The Effect of Environmental Concerns upon Intent to Visit. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8736–8755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Sayuti, N.M. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in Halal Food Purchasing. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2011, 21, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-C.P.; Chan, F. Surveying Data on Consumer Green Purchasing Intention: A Case in New Zealand. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2015, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Irianto, H. Consumers’ Attitude and Intention towards Organic Food Purchase: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behavior in Gender Perspective. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, G. How Stable Is the Value Basis for Organic Food Consumption in China? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Alfaro, J.A.; Mejía-Villa, A.; Ormazabal, M. ECO-Labels as a Multidimensional Research Topic: Trends and Opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Rosenthal, S. Signaling the Green Sell: The Influence of Eco-Label Source, Argument Specificity, and Product Involvement on Consumer Trust. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.-H.; Chin, C.-L.; Wong, W.P.-M. The Implementation of Green Marketing Tools in Rural Tourism: The Readiness of Tourists? J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.T.K. Understanding the Effects of Eco-Label, Eco-Brand, and Social Media on Green Consumption Intention in Ecotourism Destinations. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.U.; Aslam, S.; Murtaza, S.A.; Attila, S.; Molnár, E. Green Marketing Approaches and Their Impact on Green Purchase Intentions: Mediating Role of Green Brand Image and Consumer Beliefs towards the Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, O.J.; Ling, K.C.; Piew, T.H. The Antecedents of Green Purchase Intention among Malaysian Consumers. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, M.A.; Md Isa, F.; Al-Qasa, K. Young Consumers’ Intention towards Future Green Purchasing in Malaysia. J. Manag. Res. 2015, 7, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. Do Satisfied Customers Really Pay More? A Study of the Relationship between Customer Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cannière, M.H.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Geuens, M. Relationship Quality and Purchase Intention and Behavior: The Moderating Impact of Relationship Strength. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Service Quality, Profitability, and the Economic Worth of Customers: What We Know and What We Need to Learn. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.S.; Ariff, M.S.B.M.; Zakuan, N.; Tajudin, M.N.M.; Ismail, K.; Ishak, N. Consumers Perception, Purchase Intention and Actual Purchase Behavior of Organic Food Products. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014, 3, 378. [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh, D.N. Influence of Consumers’ Socio-Economic Characteristics and Attitude on Purchase Intention of Green Products. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 4, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Gopinath, C. Antecedents of Environmental Conscious Purchase Behaviors. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 14, 979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.-I.R.M.; Imlawi, J.; Al-Mashaqba, A.M. Investigating the Moderating Effects of Self-Efficacy, Age and Gender in the Context of Nursing Mobile Decision Support Systems Adoption: A Developing Country Perspective. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2018, 12, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doanh, D.C. Of of Entrepreneurship: Self-Efficacy The Moderating on the An Cognitive Empirical Role. Explor. Link Entrep. Capab. Cogn. Behav. 2021, 17, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Zainal, N.C.; Puad, M.H.M.; Sani, N.F.M. Moderating Effect of Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Knowledge, Attitude and Environment Behavior of Cybersecurity Awareness. Asian Soc. Sci. 2022, 18, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Yeh, C.-H.; Liao, Y.-W. What Drives Purchase Intention in the Context of Online Content Services? The Moderating Role of Ethical Self-Efficacy for Online Piracy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.L.; Rahim, S.A.; Pawanteh, L.; Ahmad, F. The Understanding of Environmental Citizenship among Malaysian Youths: A Study on Perception and Participation. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaver-Cohen, D. Moral Climate in Business Firms: A Conceptual Framework for Analysis and Change. J. Bus. Eth. 1998, 17, 1211–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Casual Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption and Use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Nhu, N.T.; Van My, D.; Thu, N.T.K. Determinants Affecting Green Purchase Intention: A Case of Vietnamese Consumers. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2019, 22, 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer Attitude–Behavioral Intention Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Eth. 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Al-Shaaban, S.; Nguyen, T.B. Consumer Attitude and Purchase Intention towards Organic Food: A Quantitative Study of China; Linnæus University, School of Business and Economics: Kalmar, Sweden, 2014; Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:723474/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Sethi, V. Determining Factors of Attitude towards Green Purchase Behavior of FMCG Products. IITM J. Manag. IT 2018, 9, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C. The Case for the Six-Point Likert Scale. 2018. Available online: https://www.quantumworkplace.com/future-of-work/the-case-for-the-six-point-likert-scale#:~:text=Asix-pointscaleencourages,helpsaccountforthisreality (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; ISBN 0226316521. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; D’Ambra, J.; Ray, P. Trustworthiness in MHealth Information Services: An Assessment of a Hierarchical Model with Mediating and Moderating Effects Using Partial Least Squares (PLS). J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Convergence of Structural Equation Modeling and Multilevel Modeling. In Handbook of Methodological Innovation in Social Research Methods; Williams, M., Vogt, W.P., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2011; pp. 562–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Kupper, L.L.; Muller, K.E. Applied Regression Analysys and Other Nultivariable Methods. In Applied Regression Analysys and Other Nultivariable Methods; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 1988; p. 718. [Google Scholar]

- Santosa, P.I.; Wei, K.K.; Chan, H.C. User Involvement and User Satisfaction with Information-Seeking Activity. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2005, 14, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; ISBN 0962262846. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; ISBN 1483276481. [Google Scholar]

- Holbert, R.L.; Stephenson, M.T. Structural Equation Modeling in the Communication Sciences, 1995–2000. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 531–551. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Skokie, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and Practice in Reporting Structural Equation Analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Testing Structural Equation Models. In Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Quantifying and Testing Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models When the Constituent Paths Are Nonlinear. Multivariate Behav. Res. 2010, 45, 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.; Tang, D.; Wu, G.; Lan, J. Understanding Intention and Behavior toward Sustainable Usage of Bike Sharing by Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. An Application of Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Young Indian Consumers’ Green Hotel Visit Intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawan, A.; Noermijati, N.; Sunaryo, S.; Aisjah, S. Green Product Buying Intentions among Young Consumers: Extending the Application of Theory of Planned Behavior. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G. Ecological Concerns about Genetically Modified (GM) Food Consumption Using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Shang, R.-A.; Lin, A.-K. The Intention to Download Music Files in a P2P Environment: Consumption Value, Fashion, and Ethical Decision Perspectives. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Tan, J.; Park, S.H. From Voids to Sophistication: Institutional Environment and MNC CSR Crisis in Emerging Markets. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sources | Survey Method | Sample Size/Country | Analysis Tools | Additional Constructs beyond TPB | Dependent Variable/ R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | Face-to-face interviews of people more than 23 of age. | 400/ Turkey | SEM, AMOS | Environmentally friendly activities, overall image, willingness to pay, satisfaction, and loyalty | Green customer behaviour 0.411 Intention to use-0.457 |

| [20] | Questionnaires from residents | 552/ China | PLS SEM | Environmental concern | Intention- 0.567 |

| [18] | Highly-educated consumers | 372/ Iran | SEM-AMOS | Corporate Social Responsibility, Trust | Intention- 0.638 |

| [19] | Online website survey | 223/China | PLS- SEM | Cognitive factor: environmental concern | Intention 0.319 |

| [21] | Questionnaire survey | 324/ China | SEM AMOS | Perceived consumer effectiveness and environmental concern | Intention 0.68 |

| [22] | Questionnaire survey | 620/ India | SEM AMOS | Perceived value and willingness to pay the premium (WPP) | Actual buying behaviour |

| [23] | Web-based survey through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk | 400/ U.S.A. | SEM AMOS | Consumer’s willingness to sacrifice for the environment | Intention --- |

| [33] | Web-based survey among teenage respondents Via Qualtrics.com. | 382/ U.S.A. | SEM LISREL | Environmentally focused attributes | Behavioural Intention --- |

| [32] | Web-based survey consumers (faculty members) | 428/among the U.S.A. | SEM AMOS | Personal norms of consumer | Green customer behaviour 0.265 |

| [34] | Hotel guests | 458/Taiwan | SEM- SPSS | Consumer’s environmental protection consciousness | Green customer behaviour -- |

| [6] | Web-based survey among consumers via My3q.com. | 559/Taiwan | SEM-AMOS | Perceived moral obligation | Consumer intention -- |

| Aspects | Classification | % | Aspects | Classification | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 39.40 | Marital status | Married | 65.0 |

| Female | 60.60 | Single | 35.0 | ||

| Total | 100 | Total | 100 | ||

| Age | 25 to 35 years | 52.0 | Educational level | SPM/O-Level | 8 |

| 35–45 years | 27.0 | STPM/A-Level | 20 | ||

| 45–55 years | 14.0 | Diploma | 28 | ||

| Above 55 years | 8.0 | Undergraduate | 27 | ||

| Total | 100 | Masters | 14 | ||

| Occupation | Public sector | 30.0 | PhD | 3 | |

| Private sector | 61.0 | Total | 100 | ||

| Self-employed | 09.0 | Religion | Muslim | 58.0 | |

| Total | 100 | Buddhist | 17.0 | ||

| Ethnicity | Chinese | 51.65 | Hindu | 3.0 | |

| Malays | 44.35 | Christian | 21.0 | ||

| Indians | 3.0 | Others | 1.0 | ||

| Others | 1.0 | Total | 100 | ||

| Total | 100 |

| Constructs | Item Loading | Alpha α | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buying Behaviour | 0.890 | 0.924 | 0.753 | ||

| When product qualities are similar, I choose eco-label food products over non-green products. | 0.821 | ||||

| I buy eco-label food products, although it is expensive compared to non-green products. | 0.903 | ||||

| If any product is non-environmentally friendly, I do not want to buy it. | 0.915 | ||||

| I buy a product which clearly states the environmental effect on eco-label. | 0.828 | ||||

| Attitude | 0.826 | 0.896 | 0.741 | ||

| I like eco-label food products because they will balance nature. | 0.840 | ||||

| I have a favourable attitude toward buying eco-label food products. | 0.901 | ||||

| I like eco-label food products as humans are severely abusing the environment. | 0.841 | ||||

| I would use eco-label food products because humans need to adapt to the natural environment. | 0.834 | ||||

| Buying Intention | 0.867 | 0.919 | 0.791 | ||

| I would like to use eco-label food products. | 0.926 | ||||

| I will buy eco-label food products if I happen to see them in a store. | 0.895 | ||||

| I would actively seek out eco-label food products in a store to purchase them. | 0.845 | ||||

| Environmental Concern | 0.833 | 0.923 | 0.857 | ||

| I pay much attention to the environment. | 0.934 | ||||

| The environmental aspect is crucial in my product choice. | 0.917 | ||||

| I am emotionally involved in environmental protection issues. | 0.902 | ||||

| Eco-Labelling | 0.874 | 0.941 | 0.888 | ||

| I am familiar with the term eco-labelling. | 0.946 | ||||

| I can recognize the eco-label seal. | 0.939 | ||||

| Environmental protection-related information is provided on the eco-label package. | 0.933 | ||||

| Perceived Behavioural Control | 0.870 | 0.920 | 0.794 | ||

| Buying eco-label food products regularly is entirely up to me. | 0.825 | ||||

| Buying eco-label food products is entirely within my control. | 0.912 | ||||

| If I wanted to, it would be easy for me to buy eco-label food products. | 0.933 | ||||

| Green Perceived Value | 0.715 | 0.838 | 0.634 | ||

| For me, the eco-label food product provides good value and meets expectations. | 0.782 | ||||

| I purchase eco-labelled food products because they focus more on environmental concerns than other products. | 0.803 | ||||

| I buy eco-labelled food products because they have higher environmental benefits than other products. | 0.803 | ||||

| Ethical Self-efficacy | 0.723 | 0.867 | 0.765 | ||

| During the necessity for consumption, I am confident to refuse non-eco-label food products. | 0.846 | ||||

| I am confident I will convince my friends/colleagues to refrain from using non-eco-label food products, even if they are necessary for them. | 0.903 | ||||

| Subjective Norms | 0.833 | 0.923 | 0.857 | ||

| People who influence my behaviour think that I should buy the eco-label food product. | 0.923 | ||||

| People who are important to me think I should buy the eco-label food product. | 0.928 | ||||

| BB | ATT | BI | EC | Eco | PBC | PV | ESE | SN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buying Behaviour | 0.868 | ||||||||

| Attitude | 0.334 | 0.861 | |||||||

| Buying Intention | 0.549 | 0.615 | 0.889 | ||||||

| Environmental Concern | 0.422 | 0.316 | 0.523 | 0.926 | |||||

| Eco-labelling | 0.796 | 0.467 | 0.649 | 0.285 | 0.942 | ||||

| Perceived Behavioural Control | 0.480 | 0.410 | 0.514 | 0.176 | 0.349 | 0.891 | |||

| Green Perceived Value | 0.483 | 0.389 | 0.569 | 0.249 | 0.385 | 0.488 | 0.796 | ||

| Ethical Self-efficacy | 0.392 | 0.373 | 0.630 | 0.269 | 0.368 | 0.542 | 0.431 | 0.875 | |

| Subjective Norms | 0.456 | 0.416 | 0.658 | 0.258 | 0.356 | 0.737 | 0.495 | 0.351 | 0.926 |

| Mean | 3.399 | 3.878 | 3.277 | 3.798 | 3.208 | 3.251 | 3.638 | 3.059 | 3.379 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.789 | 0.639 | 0.814 | 0.701 | 0.913 | 0.725 | 0.744 | 0.766 | 0.821 |

| Skewness | −0.274 | −0.416 | −0.220 | −0.400 | −0.257 | 0.147 | −0.628 | −0.028 | −0.335 |

| Kurtosis | 0.388 | 0.363 | −0.354 | 1.039 | −0.110 | −0.475 | 1.195 | −0.687 | −0.302 |

| BB | ATT | BI | EC | Eco | PBC | PV | ESE | SN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buying Behaviour | -- | ||||||||

| Attitude | 0.377 | -- | |||||||

| Buying Intention | 0.623 | 0.722 | -- | ||||||

| Environmental Concern | 0.488 | 0.374 | 0.615 | -- | |||||

| Eco-labelling | 0.898 | 0.539 | 0.743 | 0.593 | -- | ||||

| Perceived Behavioural Control | 0.543 | 0.472 | 0.585 | 0.400 | 0.586 | -- | |||

| Green Perceived Value | 0.598 | 0.483 | 0.709 | 0.484 | 0.665 | 0.402 | -- | ||

| Ethical Self-efficacy | 0.494 | 0.485 | 0.803 | 0.472 | 0.547 | 0.553 | 0.581 | -- | |

| Subjective Norms | 0.529 | 0.498 | 0.775 | 0.426 | 0.580 | 0.404 | 0.573 | 0.854 | -- |

| BB | ATT | BI | PBC | SN | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buying Behaviour | 0.50 | |||||

| Attitude | 1.569 | 0.17 | ||||

| Buying Intention | 1.875 | 0.89 | ||||

| Environmental Concern | 1.280 | 1.446 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Eco-labelling | 2.115 | |||||

| Perceived Behavioural Control | 1.401 | 1.638 | 0.12 | |||

| Green Perceived Value | 1.385 | 1.826 | ||||

| Ethical Self-efficacy | 1.709 | 1.973 | ||||

| Subjective Norms | 2.784 | 0.25 |

| Fit Indices | Measurement Values for CFA | Meas. Values for Structural Model | Standards with Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 2.501 | 2.742 | <3 | [92] |

| IFI | 0.942 | 0.922 | >0.900 | [93] |

| NFI | 0.921 | 0.912 | >0.900 | [93] |

| CFI | 0.933 | 0.911 | >0.900 | [94] |

| GFI | 0.913 | 0.903 | >0.900 | [93] |

| AGFI | 0.921 | 0.916 | >0.900 | [95] |

| TLI | 0.934 | 0.927 | ≥0.90 | [96] |

| SRMR | 0.045 | 0.066 | <0.080 | [93] |

| RMSEA | 0.067 | 0.071 | <0.080 | [96,97] |

| Hypotheses | STD Beta | STD Error | t-Values | p-Values | Significance (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: PV → ATT | 0.325 | 0.040 | 5.698 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2: PV → BI | 0.117 | 0.042 | 2.660 *** | 0.008 | Supported |

| H3: PV → SN | 0.440 | 0.060 | 7.555 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4: PV → PBC | 0.198 | 0.057 | 3.908 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5: EC → ATT | 0.165 | 0.032 | 3.182 *** | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6: EC → SN | 0.141 | 0.046 | 2.772 *** | 0.006 | Supported |

| H7: EC → PBC | 0.226 | 0.048 | 4.601 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H8: EC → BI | 0.096 | 0.029 | 2.729 *** | 0.006 | Supported |

| H9: ATT → BI | 0.313 | 0.048 | 8.810 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H10: SN → BI | 0.358 | 0.035 | 9.492 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H11: PBC → BI | 0.084 | 0.024 | 3.004 *** | 0.003 | Supported |

| H12: Eco → BI | 0.414 | 0.033 | 9.526 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H13: BI → BB | 0.706 | 0.053 | 13.34 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H14: EC → ATT → BI | 0.109 | 0.014 | 2.998 *** | 0.002 | Supported |

| H15: EC → SN → BI | 0.138 | 0.016 | 2.668 *** | 0.007 | Supported |

| H16: EC → PBC → BI | 0.043 | 0.006 | 2.520 ** | 0.011 | Supported |

| H17: ESE×PV → BI | 0.108 | 0.047 | 2.300 ** | 0.021 | Supported |

| H18: ESE×ATT → BI | −0.056 | 0.034 | −1.676 | 0.094 | Not Supported |

| H19: ESE×SN → BI | −0.040 | 0.042 | −0.154 | 0.878 | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, S.S.; Wang, C.-K.; Masukujjaman, M.; Ahmad, I.; Lin, C.-Y.; Ho, Y.-H. Buying Behaviour towards Eco-Labelled Food Products: Mediation Moderation Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032474

Alam SS, Wang C-K, Masukujjaman M, Ahmad I, Lin C-Y, Ho Y-H. Buying Behaviour towards Eco-Labelled Food Products: Mediation Moderation Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032474

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Syed Shah, Cheng-Kun Wang, Mohammad Masukujjaman, Ismail Ahmad, Chieh-Yu Lin, and Yi-Hui Ho. 2023. "Buying Behaviour towards Eco-Labelled Food Products: Mediation Moderation Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032474

APA StyleAlam, S. S., Wang, C.-K., Masukujjaman, M., Ahmad, I., Lin, C.-Y., & Ho, Y.-H. (2023). Buying Behaviour towards Eco-Labelled Food Products: Mediation Moderation Analysis. Sustainability, 15(3), 2474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032474