Spirituality and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Word Frequency Analysis and an Agenda for Research in Pacific Island Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Social Context, Study Framework, and Intended Contribution

3. Methodology

- They address the government requirement that all registered Australian charities fulfil for purposes of government department accountability (Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission Act 2012);

- They are audited by a qualified entity in accordance with Australian Government requirements (Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission Act 2012);

- They address a growing global emphasis on corporate governance and disclosure norms;

- They may facilitate improvements in the quality of textual narratives in corporate reporting [21];

- They are publicly available documents and therefore readily accessible.

4. Results and Discussion

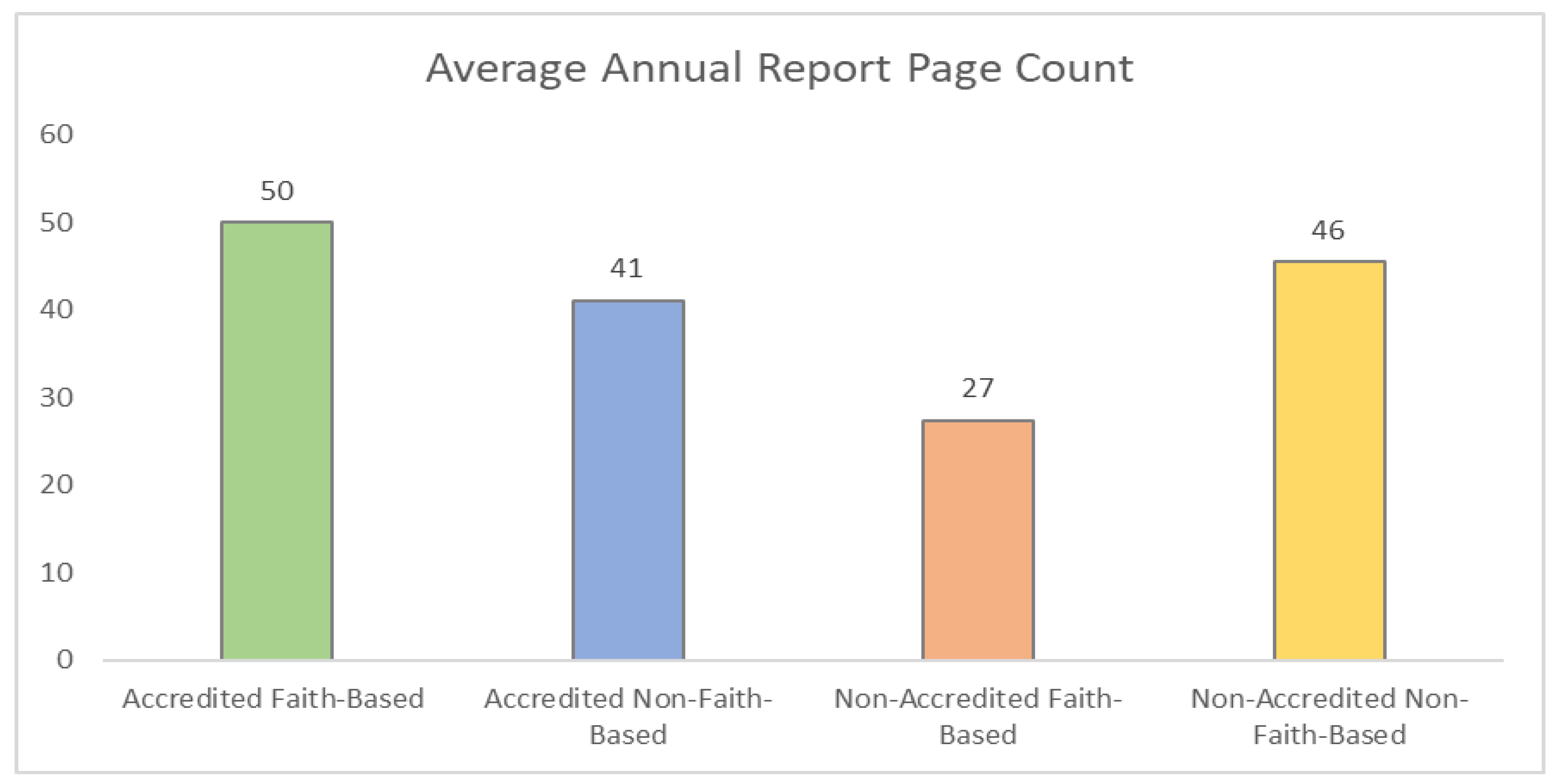

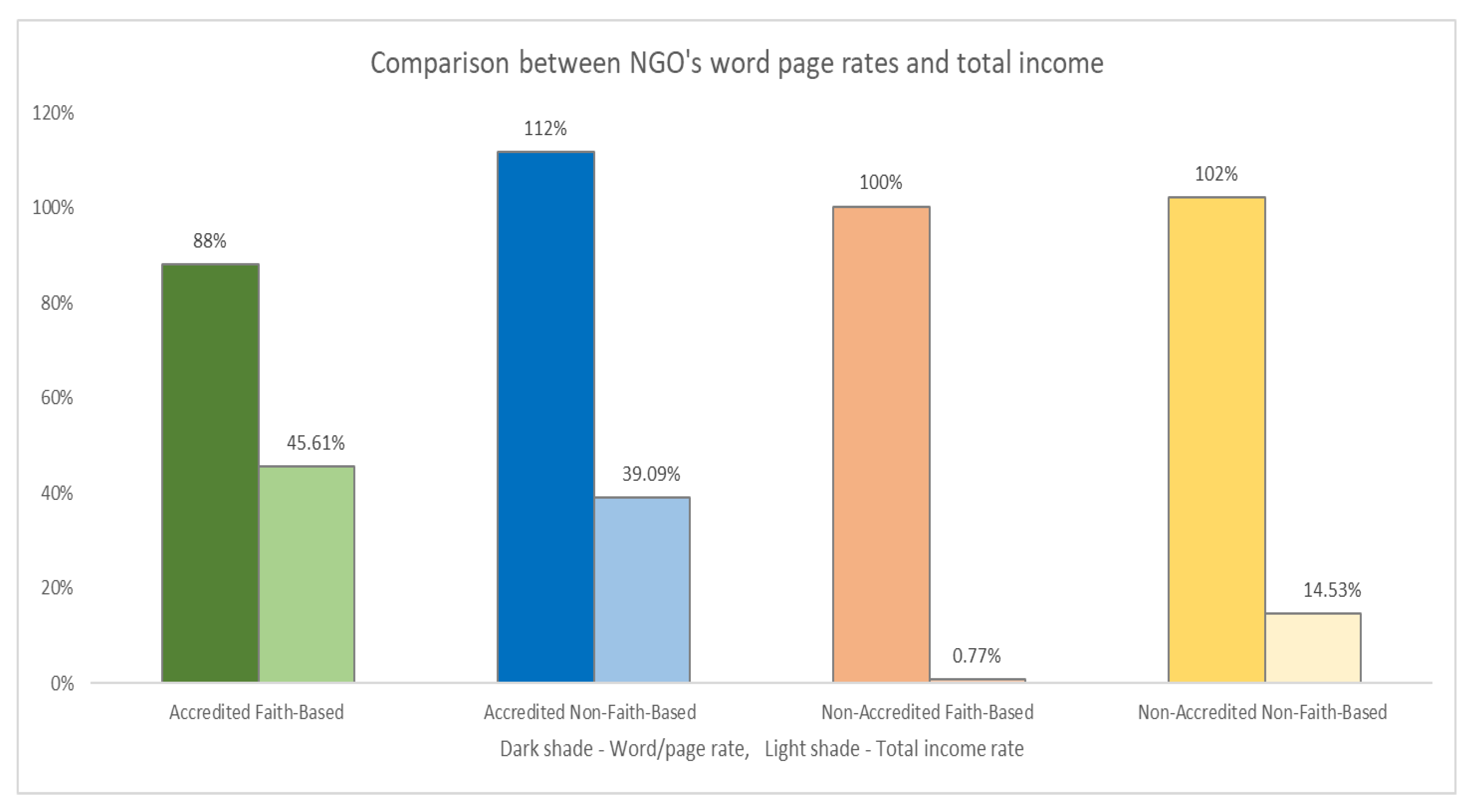

4.1. Report Lengths

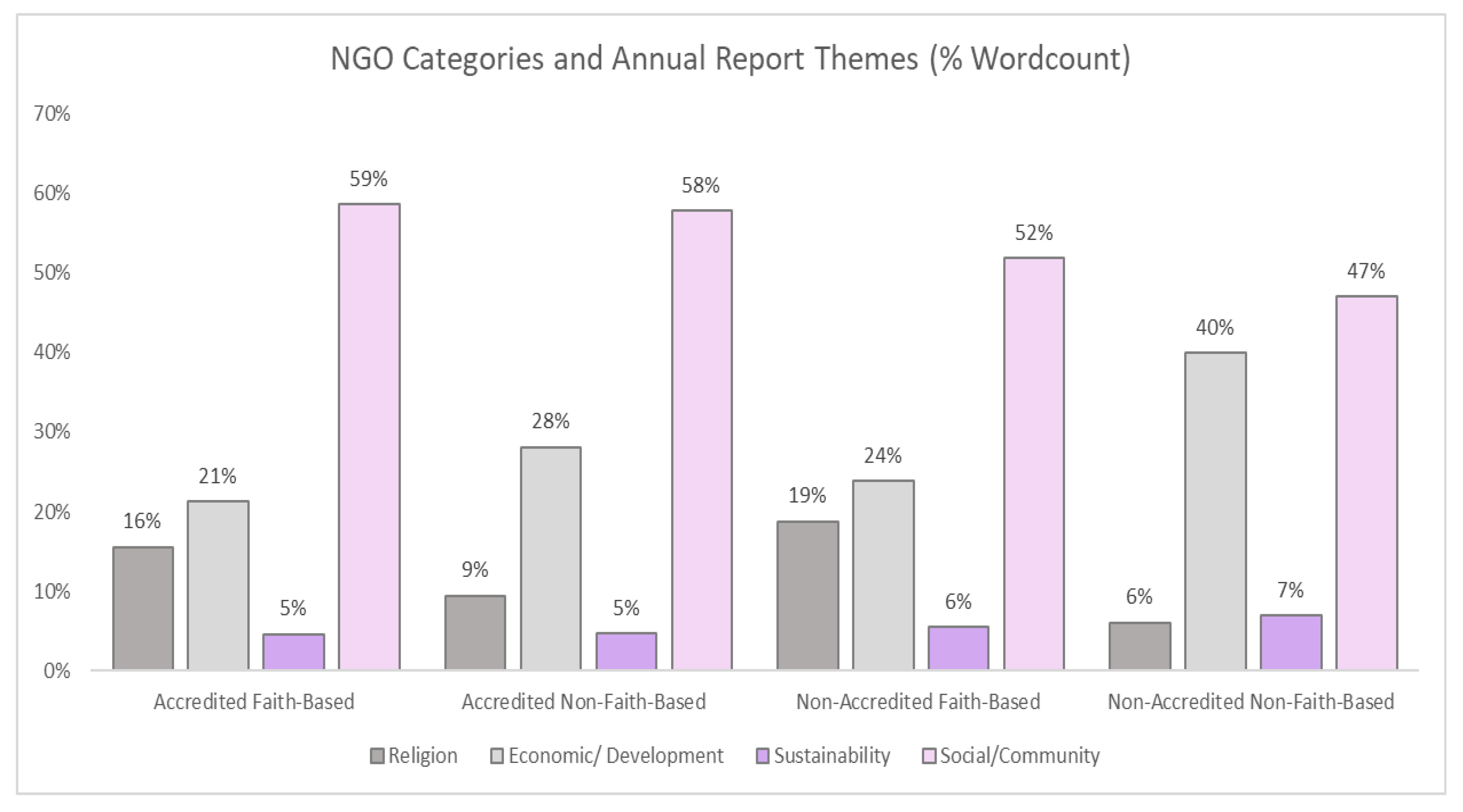

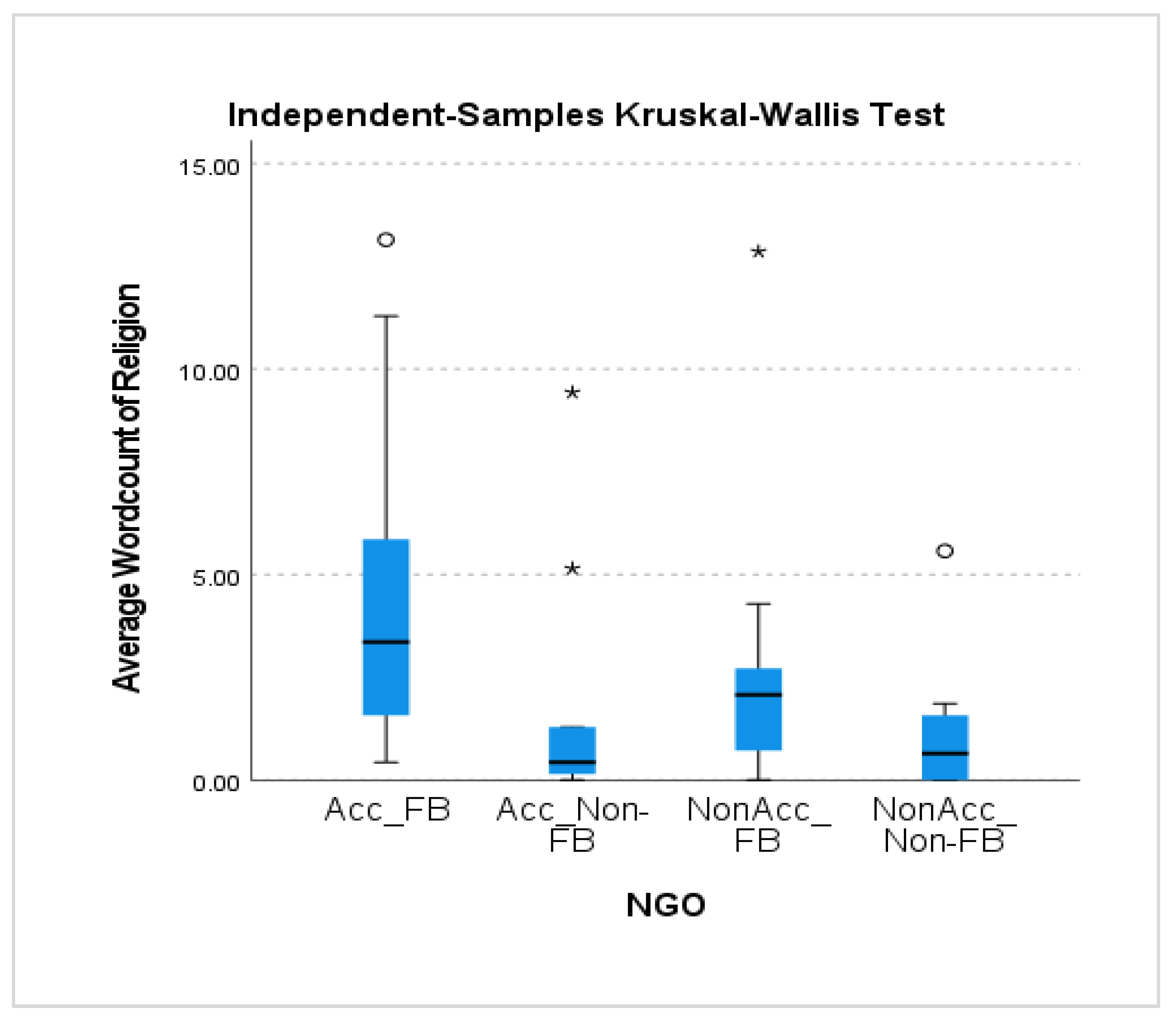

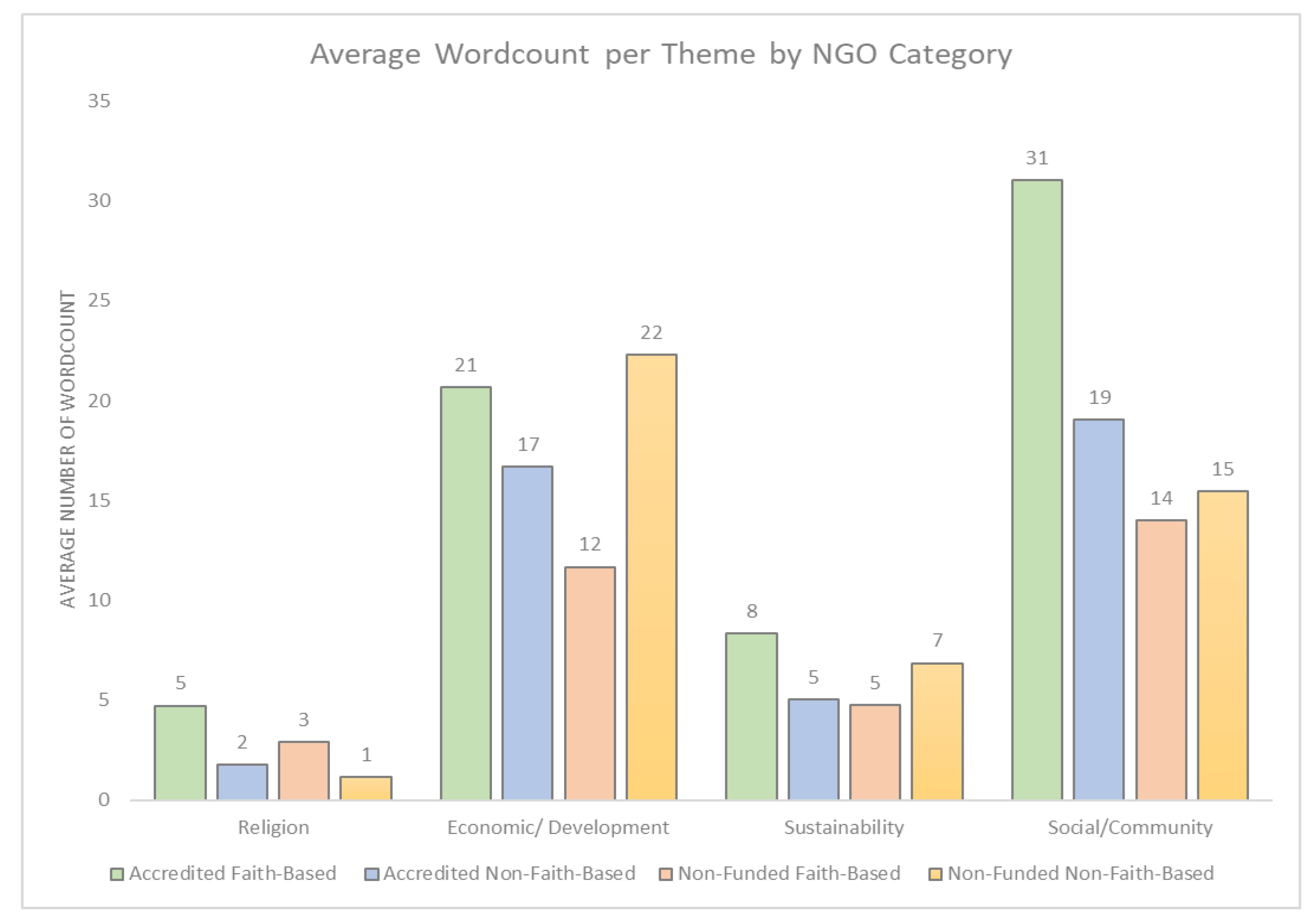

4.2. Reporting Areas

4.3. Critical Analysis: Limitations and Opportunities for Future Quantitative Research

4.4. Critical Analysis: Limitations and Opportunities for Future Qualitative Research

4.5. Synthesis: An Agenda for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luetz, J.M.; Nunn, P.D. Climate Change Adaptation in the Pacific Islands: A Review of Faith-Engaged Approaches and Opportunities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetz, J.M.; Nunn, P.D. Beyond Belief; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, K.E.; Clissold, R.; Westoby, R.; Piggott-McKellar, A.E.; Kumar, R.; Clarke, T.; Namoumou, F.; Areki, F.; Joseph, E.; Warrick, O.; et al. An assessment of community-based adaptation initiatives in the Pacific Islands. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Ulluwishewa, R.; Abubakar, I.R.; Mifsud, M.; LeVasseur, T.J.; Correia, V.; Consorte-McCrea, A.; Paço, A.; Fritzen, B.; et al. Linking sustainability and spirituality: A preliminary assessment in pursuit of a sustainable and ethically correct world. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; O’Neill, S. Maladaptation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; O’Neill, S.J. Minimising the risk of maladaptation. In Climate Adaptation Futures; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Nalau, J. (Eds.) Limits to Climate Change Adaptation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, B. Remembrance of the Colonial Past in the French Islands of the Pacific: Speeches, Representations, and Commemorations. Contemp. Pac. 2015, 27, 337–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D.; Mulgrew, K.; Scott-Parker, B.; Hine, D.W.; Marks, A.D.G.; Mahar, D.; Maebuta, J. Spirituality and attitudes towards Nature in the Pacific Islands: Insights for enabling climate-change adaptation. Clim. Chang. 2016, 136, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, H. Three stories of Noah: Navigating religious climate change narratives in the Pacific Island region. Geo: Geogr. Environ. 2018, 5, e00068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertana, A. The Impact of Faith-Based Narratives on Climate Change Adaptation in Narikoso, Fiji. Anthr. Forum 2020, 30, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Agrawal, R. Sustainable development and spirituality: A critical analysis of GNH index. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1919–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson-Nolte, J.; Nunn, P.D.; Millear, P. Influence of spiritual beliefs on autonomous climate-change adaptation: A case study from Ono Island, southern Fiji. In Beyond Belief—Opportunities for Faith-Engaged Approaches to Climate-Change Adaptation in the Pacific Islands; Luetz, J.M., Nunn, P.D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 345–375. [Google Scholar]

- Kempf, W. Introduction: Climate Change and Pacific Christianities. Anthr. Forum 2020, 30, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. DFAT and NGOs: Effective development partners, Commonwealth of Australia; Office of Development Effectiveness, Evaluation of the Australian NGO Cooperation Program Annexes: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn, P. Responding to the challenges of climate change in the Pacific Islands: Management and technological imperatives. Clim. Res. 2009, 40, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D. The end of the Pacific? Effects of sea level rise on Pacific Island livelihoods. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2013, 34, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaught, R.; McGregor, K.; Kensen, M.; Hales, R.; Nalau, J. Visualising the invisible: Collaborative approaches to local-level resilient development in the Pacific Islands region. Commonw. J. Local Gov. 2022, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalau, J.; Handmer, J.; Dalesa, M.; Foster, H.; Edwards, J.; Kauhiona, H.; Yates, L.; Welegtabit, S. The practice of integrating adaptation and disaster risk reduction in the south-west Pacific. Clim. Dev. 2015, 8, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haj, M.; Alves, P.; Rayson, P.; Walker, M.; Young, S. Retrieving, classifying and analysing narrative commentary in unstructured (glossy) annual reports published as PDF files. Account. Bus. Res. 2019, 50, 6–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.; Tooley, S.; Fatseas, V.; Brown, A. An Analysis of the Qualitative Characteristics of Management Commentary Reporting by New Zealand Companies. Australas. Account. Bus. Finance J. 2011, 5, 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J.; Petty, R.; Yongvanich, K.; Ricceri, F. Using content analysis as a research method to inquire into intellectual capital reporting. J. Intellect. Cap. 2004, 5, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, P.; Bouten, L.; Van Liedekerke, L.; De Moor, L.; Christiaens, J. Voluntary Disclosure of Corporate Social Responsibility by Belgian Listed Firms: A Content Analysis of Annual Reports; HUB Research Paper 2007/29; Production Planning and Control; Hogeschool—Universiteit Brussel, Faculteit Economie en Management: Brussels, Belgium, 2007; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, P.; Stanton, J. Corporate annual reports: Research perspectives used. Accounting, Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 478–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; McInnes, B.; Fearnley, S. A methodology for analysing and evaluating narratives in annual reports: A comprehensive descriptive profile and metrics for disclosure quality attributes. Account. Forum 2004, 28, 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westergren, A.; Edin, K.; Christianson, M. Reproducing normative femininity: Women’s evaluations of their birth experiences analysed by means of word frequency and thematic analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAMOGGIA, A.; Riedel, B.; Ruggeri, A. Social media exploration for understanding food product attributes perception: The case of coffee and health with Twitter data. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3815–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetz, J.M.; Walid, M. Social Responsibility Versus Sustainable Development in United Nations Policy Documents: A Meta-Analytical Review of Key Terms in Human Development Reports; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 301–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creative Cloud. Adobe Acrobat PRO DC; Continuous Release, Version 2022.002.20191; Adobe Systems Incorporated: San Jose, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, R.G. How to Run a Kruskal-Wallis Test in SPSS? SPSS Tutorials: Nonparametric Tests. 2023. Available online: https://www.spss-tutorials.com/kruskal-wallis-test-in-spss/ (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, D.N.; Hedstrom, L.J.; Hughes, L.L.; Leaf, J.A.; Saunders, C. Toward a Humanistic-Phenomenological Spirituality. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1988, 28, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawawi, N.F.M.; Wahab, S.A. Organisational sustainability: A redefinition? J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S. The Ethical and Ecological Limits of Sustainability: A Decolonial Approach to Climate Change in Higher Education. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 35, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telleria, J. Power relations? What power relations? The de-politicising conceptualisation of development of the UNDP. Third World Q. 2017, 38, 2143–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Ha’Apio, M.O.; Lütz, J.M.; Li, C. Climate change adaptation as a development challenge to small Island states: A case study from the Solomon Islands. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 107, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetz, J.; Havea, P.H. “We’re Not Refugees, We’ll Stay Here Until We Die!”—Climate Change Adaptation and Migration Experiences Gathered from the Tulun and Nissan Atolls of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggott-McKellar, A.E.; McNamara, K.E.; Nunn, P.D.; Sekinini, S.T. Moving People in a Changing Climate: Lessons from Two Case Studies in Fiji. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, H.R.; Sutton, A.J.; Borenstein, M. (Eds.) Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Choudry, A. Against the Flow: Maori Knowledge and Self-Determination Struggles Confront Neoliberal Globalization in Aotearoa/New Zealand. In Indigenous Knowledge and Learning in Asia/Pacific and Africa; Kapoor, D., Shizha, E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickford, J.R.; King, S. Language and linguistics on trial: Hearing Rachel Jeantel (and other vernacular speakers) in the courtroom and beyond. Language 2016, 92, 948–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saft, S. Language and Social Justice in Context: Hawai’i as a Case Study, 1st ed.; Springer International/Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Punch, K.F. Social Research: Quantitative & Qualitative Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, K.; Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVIVO, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber, S.N. The Practice of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M.; Maxwell, K.; Nuunoq; Pedersen, H.; Greeno, D.; Jingwas, N.; Blair, J.G.; Hugu, S.; Mustonen, T.; Murtomäki, E.; et al. Empowering her guardians to nurture our Ocean’s future. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2021, 32, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.C.; Gauthier, N.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Bird, R.B.; Boivin, N.; Díaz, S.; Fuller, D.Q.; Gill, J.L.; Kaplan, J.O.; Kingston, N.; et al. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, R.A.; Nunn, P.D. Integration of indigenous knowledge and disaster risk reduction: A case study from Baie Martelli, Pentecost Island, Vanuatu. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2012, 3, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Matandirotya, N.R.; Lütz, J.M.; Alemu, E.A.; Brearley, F.Q.; Baidoo, A.A.; Kateka, A.; Ogendi, G.M.; Adane, G.B.; Emiru, N.; et al. Impacts of climate change to African indigenous communities and examples of adaptation responses. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunkaporta, T. Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World; Text Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luetz, J.M.; Nichols, E.; du Plessis, K.; Nunn, P.D. Spirituality and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Word Frequency Analysis and an Agenda for Research in Pacific Island Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032201

Luetz JM, Nichols E, du Plessis K, Nunn PD. Spirituality and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Word Frequency Analysis and an Agenda for Research in Pacific Island Countries. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032201

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuetz, Johannes M., Elizabeth Nichols, Karen du Plessis, and Patrick D. Nunn. 2023. "Spirituality and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Word Frequency Analysis and an Agenda for Research in Pacific Island Countries" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032201

APA StyleLuetz, J. M., Nichols, E., du Plessis, K., & Nunn, P. D. (2023). Spirituality and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Word Frequency Analysis and an Agenda for Research in Pacific Island Countries. Sustainability, 15(3), 2201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032201