Why International Conciliation Can Resolve Maritime Disputes: A Study Based on the Jan Mayen Case

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Jan Mayen Conciliation

2.1. Background of the Dispute and the Establishment of the Conciliation Commission

2.2. Dispute Investigation and Resolution

2.2.1. Conciliation Commission Conducts Independent Investigation

2.2.2. Commission Recommendations and Dispute Resolution

3. Why Conciliation Could Be the Option for Disputing Parties

3.1. The Parties Have Dominant and Final Decision-Making Power over the Settlement of Disputes

3.2. The Commission Can Apply Law and Procedural Rules in A More Flexible Way

3.3. The Commission Provides Independent Third-Party Recommendations

3.4. The Political and Time Costs of Dispute Settlement Are Relatively Low

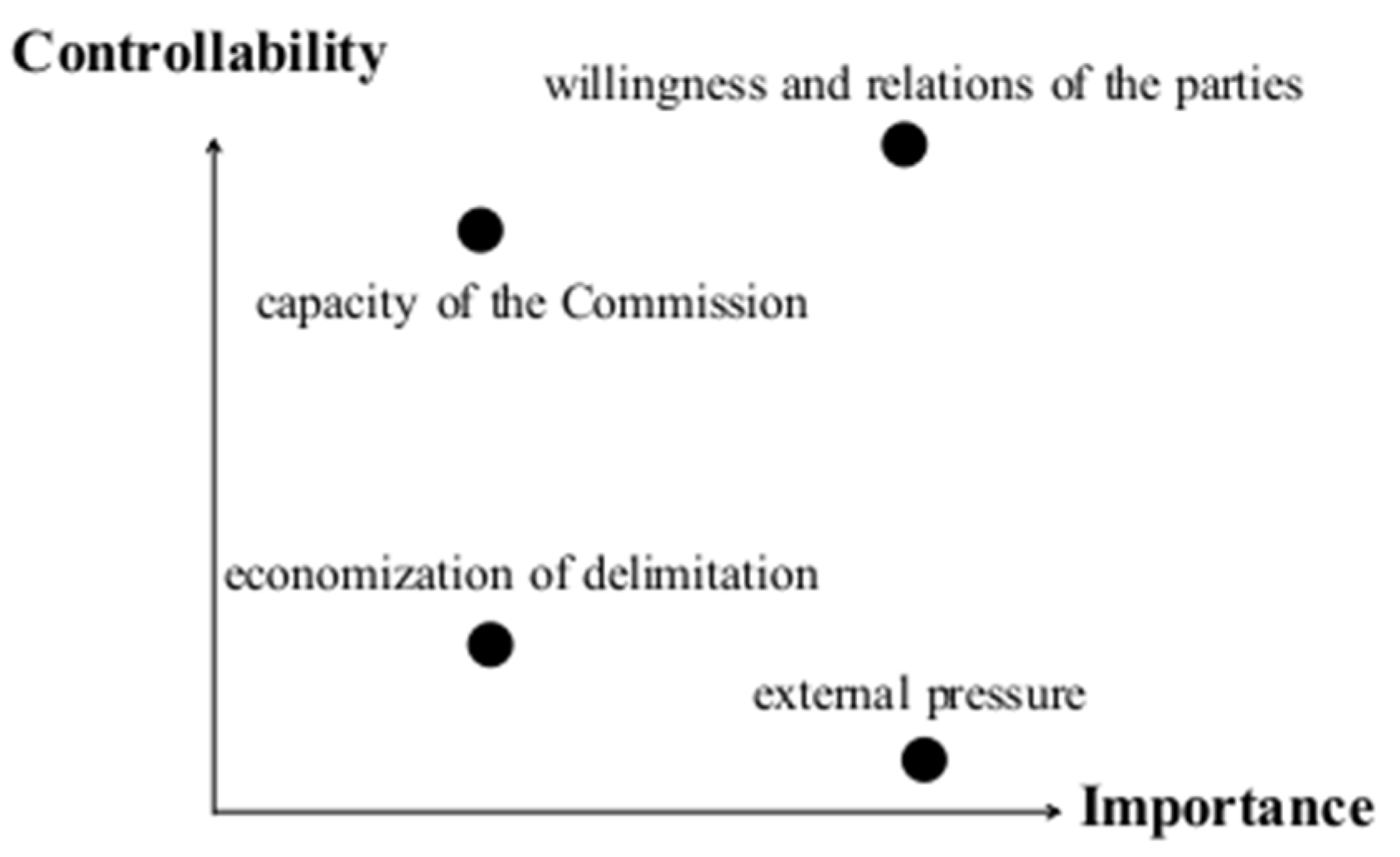

4. Key Factors Affecting the Success of Conciliation

4.1. The Willingness and Diplomatic Relations of Disputing Parties

4.2. External Pressure

4.3. Economization of Maritime Delimitation

4.4. Composition and Coordination Capacity of the Commission

5. Systemic Effect of Resolving Maritime Disputes through Conciliation

5.1. Direct and Intentional Effects: Resolved Disputes, Maintained Interests, and Good Relations

5.2. Direct but Unintentional Effects: Promoting the Stability of the Regional Power Structure

5.3. Indirect but Intentional Effects: Laying the Foundation for Resource Development and Governance in Disputed Sea Area

5.4. Indirect and Unintentional Effects: Promoting Development of International Conciliation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cot, J.-P. Conciliation. In The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law; Wolfrum, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 577–578. [Google Scholar]

- Tomuschat, C.; Mazzeschi, R.P.; Thürer, D. (Eds.) Conciliation in International Law: The OSCE Court of Conciliation and Arbitration; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, S. Conciliation and the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Ocean. Dev. Int. Law 2013, 44, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law No. 41 of 1 June 1979 Concerning the Territorial Sea, the Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf. Article 3, 5, 7. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/ICSP15/SEAFO-ICSP15Contribution.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Royal Decree of 31 May 1963 Relating to the Sovereignty of Norway over the Sea-Bed and Subsoil outside the Norwegian Coast. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/NOR_1963_Decree.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Institute of International Law, International Conciliation. 1961. Available online: https://www.idi-iil.org/app/uploads/2017/06/1961_salz_02_en.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Article 121. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Richardson, E.; Andersen, H.; Evensen, J. Report and Recommendations to the Governments of Iceland and Norway. Int. Leg. Mater. 1981, 20, 801–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, E. The Delimitation of the Continental Shelf of Jan Mayen. Arch. Völkerrechts 1983, 21, 495. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthau, H.J. Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, 7th ed.; Peking University Press: Beijing, China; McGraw-Hill Education (Asia) Co.: Singapore, 2005; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of International Law, Regulations on the Procedure of International Conciliation. 1961. Articles 1–2. Available online: https://www.idi-iil.org/app/uploads/2017/06/1961_salz_02_en.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- United Nations Model Rules for the Conciliation of Disputes between States. Articles 1–2. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/203620 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- PCA Optional Conciliation Rules. Available online: https://docs.pca-cpa.org/2016/01/Permanent-Court-of-Arbitration-Optional-Conciliation-Rules.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Chongli, X. Political and Legal Solutions to International Disputes. J. Int. Stud. 2018, 2, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, S.M.G. Diplomatic Dispute Settlement: The Use of Inter-State Conciliation; T. M. C. Asser Press: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Lauterpacht, H. The Function of Law in the International Community; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, M. Rapport du Conseil Fédéral à l’Assemblée Fédérale Concernant Les Traités Internationaux d’arbitrage. Feuille Fédérale Suisse 1919, 5, 809–826. [Google Scholar]

- ICJ. Maritime Delimitation in the Area between Greenland and Jan Mayen (Denmark v. Norway), Judgment, 14 June 1993, para. 86. Available online: https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/78 (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Cot, J.-P. International Conciliation; Europa Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K.-c. Some Special Approaches for Reaching Equitable Solutions of Ocean Boundary Disputes. Natl. Taiwan Univ. Law J. 1986, 16, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Agreement on the Continental Shelf between Iceland and Jan Mayen. 1981. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/TREATIES/ISL-NOR1981CS.PDF (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- ICJ. Questions Relating to the Seizure and Detention of Certain Documents and Data (Timor-Leste v. Australia), Application Instituting Proceedings. 17 December 2013, Paras. 4–11. Available online: https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/156 (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Annex V of United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Article 7. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Annuaire-Yearbook of ICJ. Available online: https://www.icj-cij.org/en/publications (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- ITLOS. Available online: https://www.itlos.org/en/main/cases/list-of-cases/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- PCA. Available online: https://pca-cpa.org/en/services/arbitration-services/unclos/ (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf. Article 1. Available online: https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/8_1_1958_continental_shelf.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Østreng, W. Reaching Agreement on International Exploitation of and Mineral Resources (With Special References to the joint development area between Jan Mayen and Iceland. Energy 1985, 10, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorhallsson, B. (Ed.) Iceland and European Integration: On the Edge; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen, J. La Délimitation entre la Norvège et L’Islande du Plateau Continental dans le Secteur de Jan Mayen. Annu. Fr. Droit Int. 1981, 27, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.J. Norwegian Security Policy for the 1980s. Coop. Confl. 1982, 17, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Congress of the United States. The U.S. Sea Control Mission: Forces, Capabilities, and Requirements; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1977; p. IX.

- National Security Decision Memorandum 137. Available online: https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nsdm-nixon/nsdm-137.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Jóhannesson, G.T. Sympathy and Self-Interest: Norway and the Anglo-Icelandic Cod Wars; Institutt for Forsvarsstudier: Oslo, Norway, 2005; pp. 83–84, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, C. The North as a Multidimensional Strategic Arena. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1990, 512, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóhannesson, G. The Jan Mayen Dispute between Iceland and Norway 1979–1981, A Study in Successful Diplomacy? Arctic Frontiers. 24 January 2013. Available online: http://gudnith.is/efni/jan_mayen_dispute_24_jan_2013 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Fairlamb, J.R. Icelandic Threat Perceptions. Nav. War Coll. Rev. 1981, 34, 71. [Google Scholar]

- 1945 US Presidential Proclamation No. 2667. Available online: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-2667-policy-the-united-states-with-respect-the-natural-resources-the-subsoil (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Article 77. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Kadagi, N.I.; Okafor-Yarwood, I.; Glaser, S.; Lien, Z. Joint Management of Shared Resources as an Alternative Approach for Addressing Maritime Boundary Disputes: The Kenya-Somalia Maritime Boundary Dispute. J. Indian Ocean. Reg. 2020, 16, 348–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankes, N. The Regime for Transboundary Hydrocarbon Deposits in the Maritime Delimitation Treaties and Other Related Agreements of Arctic Coastal States. Ocean. Dev. Int. Law 2016, 47, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E. Jan Mayen in Perspective. Am. J. Int. Law 1988, 82, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jervis, R. System Effects: Complexity in Political and Social Life; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 29–67. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, R.R. Maritime Delimitation in the Jan Mayen Area. Mar. Policy 1985, 9, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydenlund, K. Lille Land—Hva Nå? Refleksjoner om Norges Utenrikspolitiske Situasjon; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 1982; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Østreng, W. Norwegian Petroleum Policy and Ocean Management: The Need to Consider Foreign Interests. Coop. Confl. 1982, 17, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J. Strengthening the NATO Alliance: Toward a Strategy for the 1980s. Nav. War Coll. Rev. 1981, 34, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson, G. Icelandic Security Policy: Context and Trends. Coop. Confl. 1982, 17, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østreng, W. The Politics of Continental Shelves: The South China Sea in a Comparative Perspective. Coop. Confl. 1985, 20, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergesen, H.O. ‘Not Valid for Oil’: The Petroleum Dilemma in Norwegian Foreign Policy. Coop. Confl. 1982, 17, 107, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memorandum of Understanding between Norway and USA Governing Prestockage and Reinforcement of Norway. 16 January 1981. Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/TRAKTATEN/traktat/1981-01-16-2/KAPITTEL_1#%C2%A71 (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Zakheim, D. NATO’s Northern Front: Developments and Prospects. Coop. Confl. 1982, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingimundarson, V. Iceland’s Security Dilemma: The End of a U.S. Military Presence. Fletcher Forum World Aff. 2007, 31, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Agreement on the Continental Shelf between Iceland and Jan Jan Mayen. 1981. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/TREATIES/isl-nor1980fcs.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- The National Energy Authority of Iceland and Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. Geology and Hydrocarbon Potential of the Jan Mayen Ridge. 1985. Available online: https://nea.is/oil-and-gas-exploration/exploration-areas/research-publications/nr/137 (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- The National Energy Authority of Iceland. Dreki—Strategic Environmental Assessment. Available online: https://nea.is/oil-and-gas-exploration/the-exploration-area/dreki---sea/ (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Parlow, A.L. Toward Distributive Justice in Offshore Natural Resources Development: Iceland and Norway in the Jan Mayen. Ocean. Coast. Law J. 2018, 23, 162–163. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/occoa23&div=7&id=&page= (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Pétursson, J.S. Technical Challenges, Viability, and Potential Environmental Impacts of Oil Production in the Dreki and Jan Mayen Ridge Region. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, 2013; pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- The National Energy Authority of Iceland. CNOOC Iceland ehf. og Petoro Iceland AS Gefa Eftir Sérleyfi til Rannsókna og Vinnslu á Kolvetni á Drekasvæðinu Milli Íslands og Jan Mayen. Available online: https://orkustofnun.is/orkustofnun/frettir/nr/1911 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Proelss, A. (Ed.) United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: A Commentary; Hart Publishing: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1841, 2321–2366. [Google Scholar]

- PCA. Report and Recommendations of the Compulsory Conciliation Commission between Timor-Leste and Australia on the Timor Sea. 9 May 2018, para. 69–70, 90, 124, 164. Available online: https://pcacases.com/web/sendAttach/2327 (accessed on 27 May 2022).

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | |

|---|---|---|

| Intentional Effects | Disputes are resolved; the interests of both parties and friendly relations are maintained | Lays the foundation for cooperation in resource development and governance in the disputed sea area |

| Unintentional Effects | The stability of the regional power structure is promoted | Promotes the practice and development of international conciliation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, L. Why International Conciliation Can Resolve Maritime Disputes: A Study Based on the Jan Mayen Case. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031830

Dong L. Why International Conciliation Can Resolve Maritime Disputes: A Study Based on the Jan Mayen Case. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031830

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Limin. 2023. "Why International Conciliation Can Resolve Maritime Disputes: A Study Based on the Jan Mayen Case" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031830

APA StyleDong, L. (2023). Why International Conciliation Can Resolve Maritime Disputes: A Study Based on the Jan Mayen Case. Sustainability, 15(3), 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031830