Study of Plans to Ensure the Sustainability of Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Necessity and Purpose of Our Research

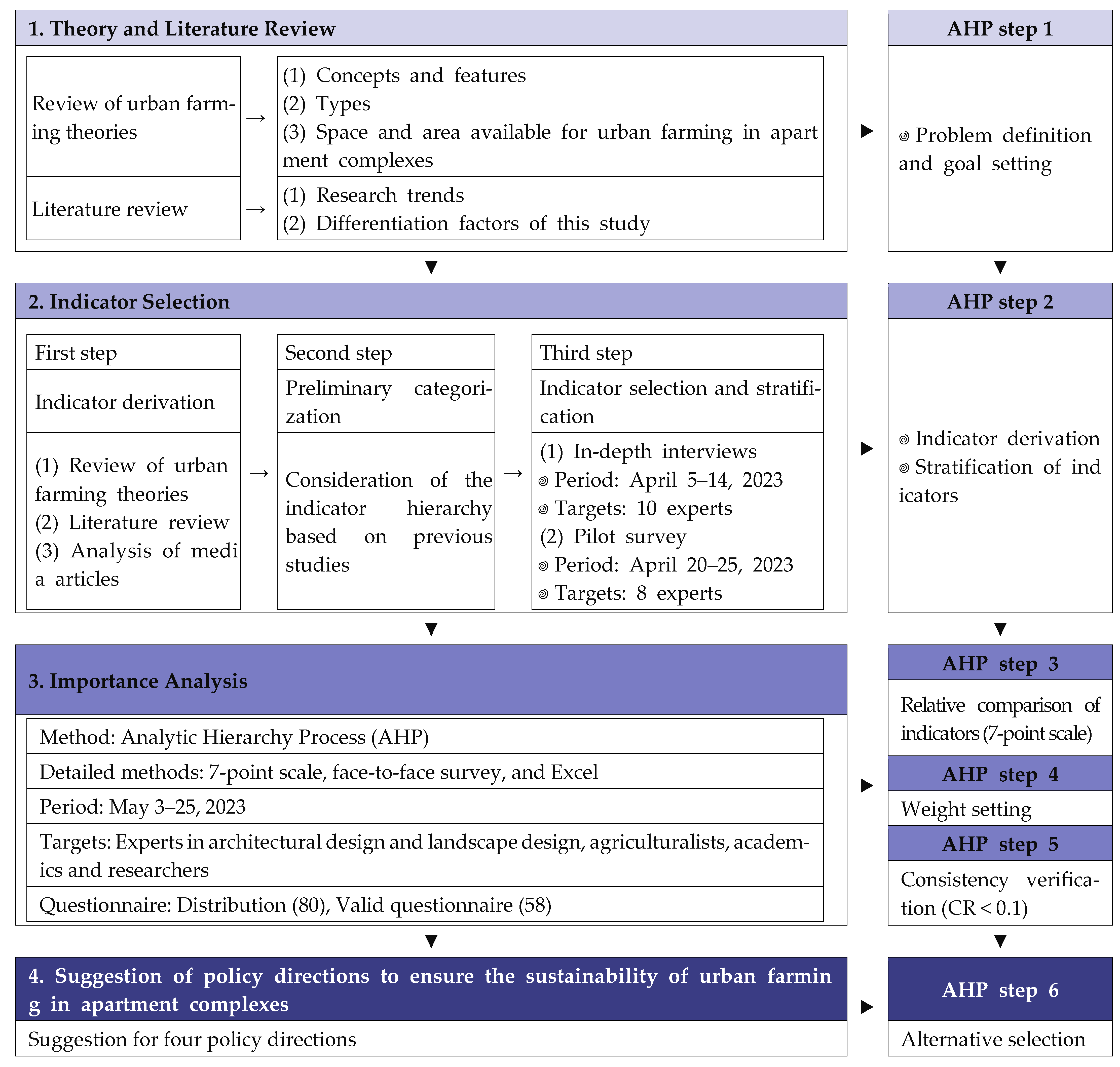

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scope of Our Study

2.1.1. Apartments

2.1.2. Metropolitan Cities

2.2. Methodology of Our Study

2.2.1. Development of the Study

2.2.2. AHP Research Methodology

3. Theory and Literature Review

3.1. Urban Farming

3.1.1. Concepts and Features of Urban Farming

3.1.2. Urban Farming Types

3.1.3. Estimation of the Available Area for Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes

3.1.4. Reviewing Urban Agriculture Practices in Apartment Complexes

3.1.5. The Current Status of the Program Promoting Urban Agriculture in Apartment Complexes

3.2. Literature Review

3.2.1. Research Trends in Previous Studies

- (1)

- Research before 2011

- (2)

- Research after 2011

- (3)

- Recent research trends

3.2.2. Differentiation Factors Associated with This Research

4. Results

4.1. Indicator Selection for Facilitating Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes

4.1.1. Indicator Derivation

- (1)

- Review of urban farming theories

- (2)

- Literature review

| First Step | Second Step | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Derivation | Literature Review 1 | Previous Studies 2 | Media Articles 3 | Preliminary Categorization |

| Absence/presence of main roads (environmental aspect) | ○ | Location condition | ||

| Vicinity of industrial areas (environmental aspect) | ○ | ○ | ||

| Size (number of households) | ○ | ○ | Complex condition | |

| Age of apartment building | ○ | |||

| Availability of rooftops for use | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Low floor area ratio | ○ | |||

| Security of water | ○ | ○ | Farming condition | |

| High sunlight | ○ | ○ | ||

| High greenspace rate | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Biotope area rate | ○ | ○ | ||

| Ease of securing cultivation soil | ○ | |||

| Presence of related specialized organizations within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | Technical and management support |

| Presence of related programs within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Presence of related case reports within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Presence of urban-farming-related NGOs within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Presence of relevant departments within administrative agencies | ○ | ○ | ○ | Public funding |

| Ordinance for administrative agency support and allocated budget | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Presence of similar support projects within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Proportion of people in their 40s or above | ○ | ○ | Status of residents | |

| Low social-activity rate | ○ | |||

| Ratio of people with high levels of experience in crop cultivation | ○ | |||

4.1.2. Indicator Selection and Stratification

- (1)

- In-depth interviews

- (2)

- Pilot survey

4.1.3. Details of the Questionnaire

4.2. Importance Analysis

4.2.1. Outline

4.2.2. Survey Results and Analysis

5. Policy Directions for Sustainable Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes

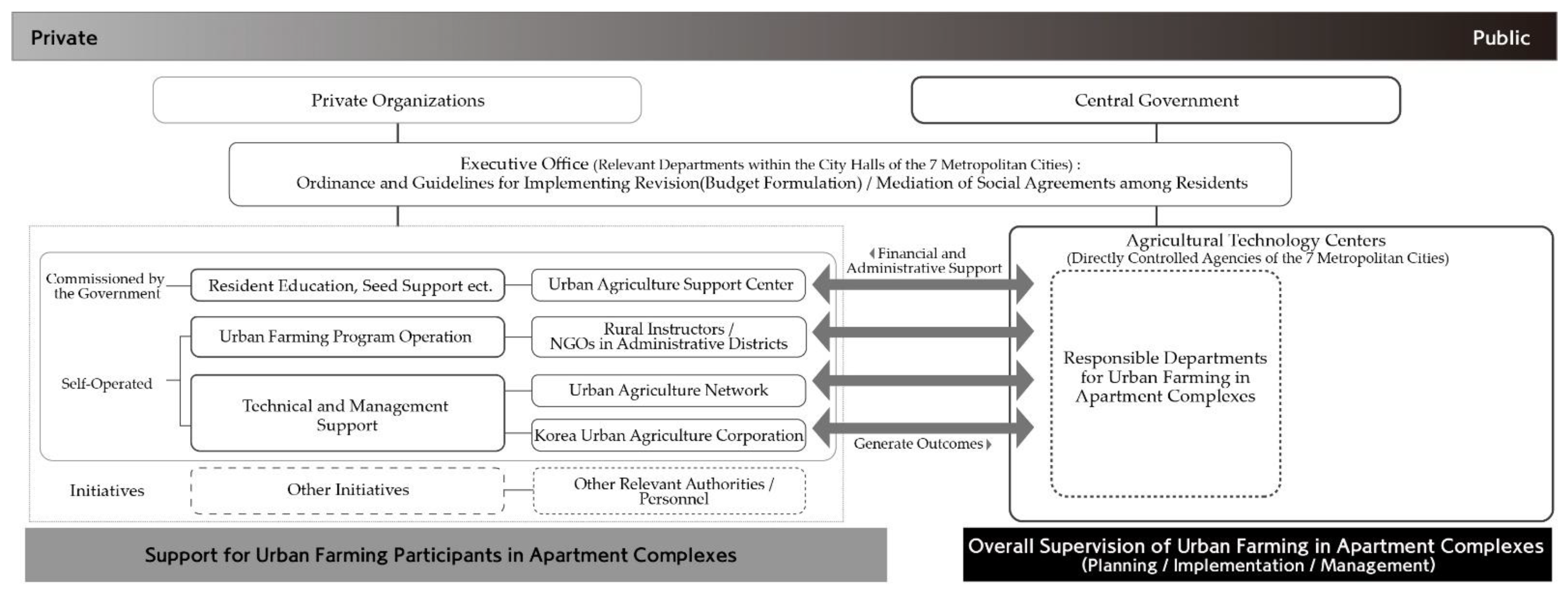

5.1. Plans to Prepare Departments in Charge of Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes

5.2. Revision of Ordinances in Support of Urban Farming and Budget Formulation

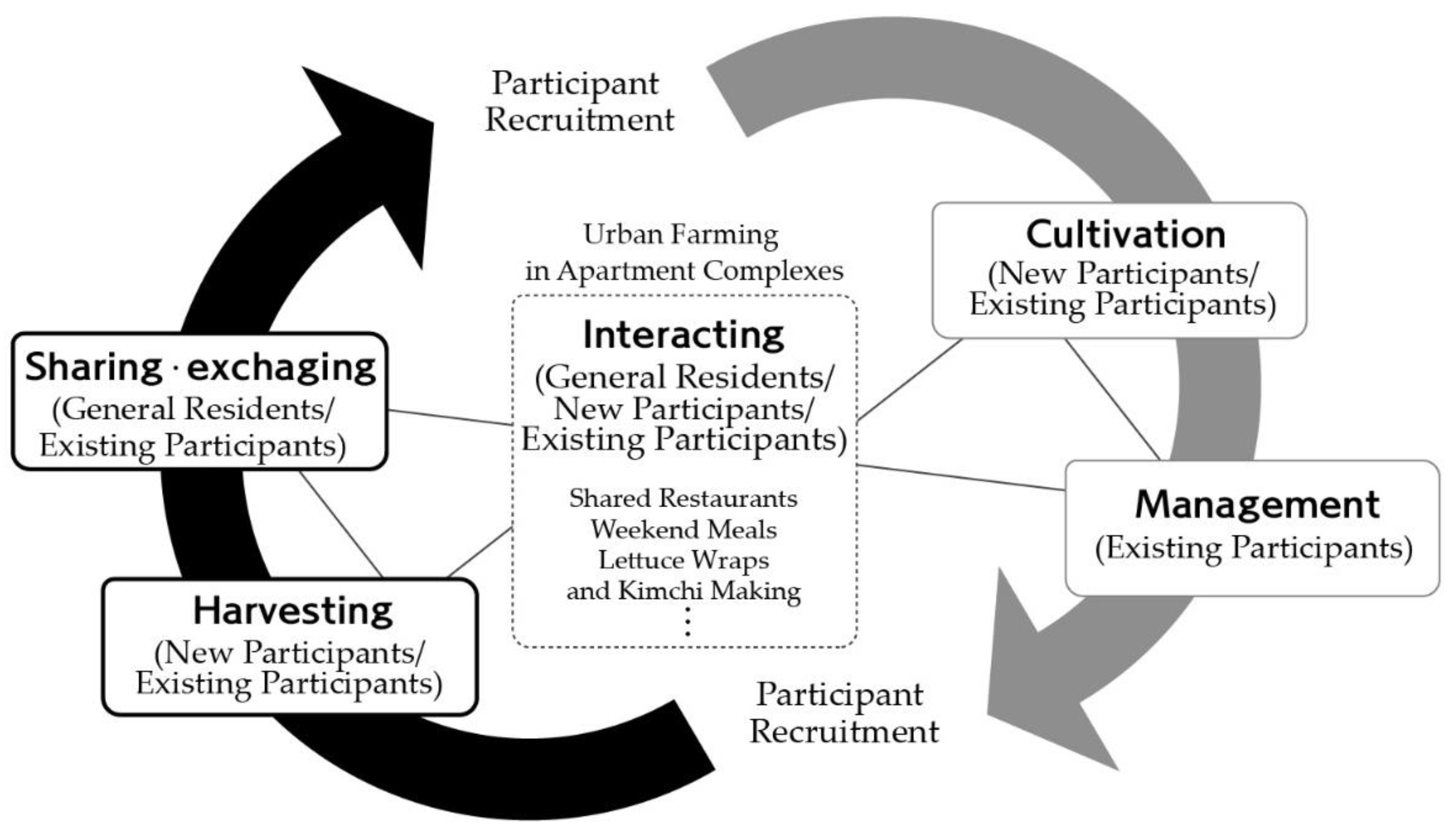

5.3. Urban-Farming Programs in Apartment Complexes

5.4. Technical and Management Support from the Public

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Study Implications

6.2. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yun, H.J.; Cho, M.K. The consideration of progressive urban park and the possibility of urban agricultural park. J. Korean Soc. Rural Plan. 2012, 18, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoang, V. Modern short food supply chain, good agricultural practices, and sustainability: A conceptual framework and case study in Vietnam. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, W.; Sulewski, P.; Mikolajczyk, J.; Król, K. Farming under urban pressure: Business models and success factors of peri-urban farms. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, M.; Clark, A.; Sherriff, G. Mainstreaming urban agriculture: Opportunities and barriers to upscaling city farming. Agronomy 2022, 12, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Clair, R.; Hardman, M.; Armitage, R.P.; Sheriff, G.S. Urban agriculture in shared spaces: The difficulties with collaboration in an age of austerity. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.S. A Study on the Landscape Architectural Way to Expand Green Space. Master’s Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.J. The study of securing urban farmland for vitalizing urban agriculture. J. Korean Urban Manag. Assoc. 2012, 25, 89–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, J.L.; Komisar, D. The integration of food and agriculture into urban planning and design practices. In Sustainable Food Planning: Evolving Theory and Practice; Viljoen, A., Wiskerke, J.S.C., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, B.G.; Choi, Y.J.; Hwang, J.I. Needs assessment for urban agricultural program. J. Korean Soc. Agric. Ext. 2011, 18, 511–529. [Google Scholar]

- Capotorti, G.; Lazzari, V.D.; Ortí, M.A. Local scale prioritisation of green infrastructure for enhancing biodiversity in peri-urban agroecosystems: A multi-step process applied in the metropolitan city of Rome (Italy). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homepage of Korean Statistical Information Service. Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_2KAA204 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Homepage of Korean Statistical Information Service. Available online: https://kosis.kr/search/search.do?query=%EB%86%8D%EA%B0%80%EC%9D%B8%EA%B5%AC (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Homepage of Korean Law Information Center. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/%EB%B2%95%EB%A0%B9/%EB%8F%84%EC%8B%9C%EB%86%8D%EC%97%85%EC%9D%98%EC%9C%A1%EC%84%B1%EB%B0%8F%EC%A7%80%EC%9B%90%EC%97%90%EA%B4%80%ED%95%9C%EB%B2%95%EB%A5%A0 (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Homepage of Korean Statistical Information Service. Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1EB001&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Homepage of Korean Statistical Information Service. Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1JU1501&vw_cd=&list_id=&seqNo=&lang_mode=ko&language=kor&obj_var_id=&itm_id=&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Homepage of Korean Law Information Center. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW//lsBylInfoPLinkR.do?lsiSeq=250719&lsNm=%EA%B1%B4%EC%B6%95%EB%B2%95+%EC%8B%9C%ED%96%89%EB%A0%B9&bylNo=0001&bylBrNo=00&bylCls=BE&bylEfYd=20230516&bylEfYdYn=Y (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Song, K.W.; Lee, Y. Re-scaling for improving the consistency of the AHP method. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 2013, 29, 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, K.K.; Lee, Y.J. The Effects of Urban Agriculture on Greenhouse Gases Reduction and Its Policy Proposals; Korea Environment Institute: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Homepage of Korean Law Information Center. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/lsSc.do?section=&menuId=1&subMenuId=15&tabMenuId=81&eventGubun=060101&query=%EA%B1%B4%EC%B6%95%EB%B2%95#undefined (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Homepage of Korean Law Information Center. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/DRF/lawService.do?OC=poweresca&target=ordin&MST=1840435&type=HTML&mobileYn= (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Kang, K.N.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, M.H. Revitalization planning of urban farming based on vegetable gardens. J. Inst. Constr. Technol. 2007, 26, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J. A study on the legal system of small garden from the viewpoint of urban regeneration. JKRDA 2010, 22, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. A study on the development of Korean kleingarten model in terms of Japanese kleingarten. KSRP 2010, 16, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.I.; Choi, Y.J.; Jang, B.G.; Rhee, S.Y. Segmentation and characteristic analysis of urban farmers behavior. Korean J. Community Living Sci. 2010, 21, 619–631. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, J.N.; Kwon, H.H. A study on evaluation and preference of urban agriculture using contingent valuation method: The case of Seoul Metropolitan Area. Seouls 2014, 15, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.I.; Kwon, J.W. Strategy and basic planning for creating an urban agricultural park: Focusing on Gosangol Village in Daegu City. J. KILA 2017, 45, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.Y.; Min, K.M.; Yoon, Y.H.; Ju, J.H. Effects of companion planting with tagetes patula on the growth and pest control of brassica campestris in rooftop urban agriculture. JESI 2022, 31, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y.S. Development of multifunctional garden box for urban agriculture. KICPD 2022, 70, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dorr, E.; Goldstein, B.; Horvath, A.; Aubry, C.; Gabrielle, B. Environmental impacts and resource use of urban agriculture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 093002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Villarino, M.T.; Urquijo, J.; Gómez Villarino, M.; García, A.I. Key insights of urban agriculture for sustainable urban development. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 45, 1441–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J. Strategies for promoting urban agriculture in Gyeonggi-do. Policy Brief 2010, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rhim, J.H.; Yoon, I.S.; Yoon, E.J.; Kang, K.N.; Ahn, T. Planning Strategies for Urban Farming in the Development Project Areas; Land & Housing Institute: Deajeon, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C.H. Study on Participation Situation and Activating Strategies of Urban Agriculture as a Hobby; Rural Development Administration: Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Joinau, B.; Križnik, B.; Lee, H.J. Rethinking Community through Urban Agriculture: A Case of Urban Gardening in Seochon Area in Seoul; National Research Council for Economics, Humanities and Social Sciences: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Homepage of Seoul. Available online: http://ebook.seoul.go.kr/Viewer/TEUXPKKDVX59 (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Kim, T.G.; Park, M.H.; Heo, J.N. Vision and Assignment for the Agriculture; Korea Rural Economic Institute: Naju, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Homepage of Seoul Legal Administration Services. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/DRF/lawService.do?OC=poweresca&target=ordin&MST=1725251&type=HTML&mobileYn= (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Jang, D.H. Policy implication for improving urban agriculture. J. Ind. Econ. Bus. 2009, 22, 979–994. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.J.; Miller, P. Collaborative planning model for brownfield regeneration. J. KILA 2015, 43, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.E. Driving projects of urban agriculture for the energy independence. Korean J. Environ. Agric. 2010, 29, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.Z.; Koo, B.H.; Park, M.O.; Kwon, H.J. A comparative study on the recognition of urban agriculture between urban farmers and public officials. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 40, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Kim, E.O.; Jo, J.E. A study on the current situation of urban agriculture program and activating plan—Focused on Anyang City. J. Community Dev. Soc. 2010, 35, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, D.H.; Soh, S.Y. A Study on Management of Urban Agriculture. In Bulletin of the Agricultural College; Jeonbuk National University: Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2005; Volume 36, pp. 86–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.G.; Cho, S.H. The analysis on the preference of urban agriculture types in accordance with lifestyle. J. KILA 2016, 44, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.R.; So, E.J.; Park, B.M.; Park, Y.J. A study on the perception of and satisfaction with urban farming management. J. KIGD 2018, 4, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.W.; Heo, C.M. Factors influencing participation intention in urban agriculture -moderating effects of household type. KJOA 2020, 28, 289–313. [Google Scholar]

| Classification | Average | Seoul | Busan | Daegu | Incheon | Gwangju | Daejeon | Ulsan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) | 776 | 605 | 771 | 885 | 1067 | 501 | 540 | 1063 |

| Population (×1000) | 3149 | 9419 | 3309 | 2357 | 2978 | 1426 | 1445 | 1106 |

| Percentage living in apartments 1 | 67% | 60% | 69% | 75% | 66% | 81% | 75% | 74% |

| Types | Details |

|---|---|

| Housing use | Urban farming using the interior, exterior, railings, and rooftops of buildings such as houses and multi-unit dwellings, or land around buildings such as houses and multi-unit dwellings |

| Neighborhood living area | Urban farming using land located in neighborhood living areas around houses and multi-unit dwellings |

| Urban | Urban farming using the interior, exterior, and rooftops of high-rise buildings in the city center or land near high-rise buildings in the city center |

| Farm/park | Urban farming using farms or city parks |

| School | Urban farming using school land and buildings for the purpose of student learning and experience |

| Categories | Space in Use | |

|---|---|---|

| Residential spaces | Interior | Entrance, Patio, Kitchen, etc. |

| Exterior | Flowerbeds of a building entrance, Rooftop, Garden, etc. | |

| Commercial & Industrial spaces | Interior | Lobby, Office, Corridor, Lounge, etc. |

| Exterior | Rooftop etc. | |

| Public land | City parks, Privately-owned public spaces, Schools, Hospitals, Welfare facilities, etc. | |

| Street spaces | Fruit trees, Roadside trees, Roadside, Traffic island, etc. | |

| Undeveloped lands | Withholding of development, Unused land | |

| Other | Spare space in the city, New space created through wall removal | |

| Categories | Scoring Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential spaces | Detached housing areas | Green areas on sites | Area × 0.5 |

| The rooftop | Area × 0.3 | ||

| Apartment housing areas | Green areas on sites | Area × 0.5 | |

| Indoor areas | 1 m2 per household | ||

| Commercial & Business spaces | Green areas on sites | Area × 0.5 | |

| The rooftop | Area × 0.3 | ||

| Residential & Commercial spaces | Green areas on sites | Area × 0.5 | |

| The rooftop | Area × 0.3 | ||

| Classification | Organizations | Departments | Dedicated Personnel (No.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Name of Departments | ||||

| Central government | Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs | × | 1 | ||

| Rural Development Administration | × | 0 | |||

| Local governments | Seoul | Seoul Metropolitan Government | Relevant department | Agricultural Support Team | 1 |

| Agricultural Technology Center | Responsible department | Department of Agricultural Education | 7 | ||

| Busan | Busan Metropolitan Government | Responsible department | Urban Agriculture Team | 4 | |

| Agricultural Technology Center | Responsible department | Civic Agricultural Team | 7 | ||

| Daegu | Daegu Metropolitan Government | Responsible department | Urban Agriculture Team | 3 | |

| Agricultural Technology Center | Responsible department | Department of Urban Agriculture | 12 | ||

| Incheon | Incheon Metropolitan Government | × | 0 | ||

| Agricultural Technology Center | Responsible department | Department of Urban Agriculture | 8 | ||

| Gwangju | Gwangju Metropolitan Government | × | 0 | ||

| Agricultural Technology Center | Responsible department | Urban Agriculture Team | 5 | ||

| Daejeon | Daejeon Metropolitan Government | × | 0 | ||

| Agricultural Technology Center | Responsible department | Urban Agriculture Team | 3 | ||

| Ulsan | Ulsan Metropolitan Government | × | 0 | ||

| Agricultural Technology Center | Relevant department | Department of Urban Agriculture | 2 | ||

| Private organizations | Commissioned by the government | Urban Agriculture Support Center (5 in Seoul and 1 in Incheon) | N/A | ||

| Self-operation | Urban Agriculture Network (1 in Seoul, 1 in Busan, 2 in Incheon, and 1 in Ulsan) | ||||

| Korea Urban Agriculture Corporation (1 in Seoul, 1 in Gwangju, and 1 in Daejeon) | |||||

| Urban Farmers Co., Ltd. (1 in Seoul and 2 in Incheon) | |||||

| Urban Farmer (5 in Seoul and 4 in Incheon) | |||||

| Other weekend farms, weekend vegetable gardens, etc. | |||||

| Types | Program | Seoul | Busan | Daegu | Incheon | Gwangju | Daejeon | Ulsan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School | Urban farming exchange experience (between cities, provinces, and institutions) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Urban farming fair/exhibition | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Urban farming tour (experience campaign) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Horticultural therapy (healing) program (farm) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Nature-experience school and nature learning center for citizens | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| Home Horticultural Plant Hospital (General Plant Hospital) | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| Urban farming expert training | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Educational program for farmers | ○ | |||||||

| Urban farming program (for the general public) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Education for female farmers | ○ | |||||||

| Green U-turn training (for those returning to rural areas) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||

| Education for farming tips (by location and crop) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Overseas training for farmers | ○ | |||||||

| Urban farming startup support | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Operation of the information support center for urban farming | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| Publication of urban agriculture books | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Pilot project of farm work safety model | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| Support for research group initiation | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Pest monitoring and technical guidance | ○ | |||||||

| Educational donation (youth psychology, emotional stability) | ○ | |||||||

| Farm/park | Urban family weekend farmer | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| School farm | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Silver farm | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| Farm for households with more than three children | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| LED plant factory | ○ | |||||||

| Sale of vegetable garden | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Housing use | Apartment-building porch (green curtain) project | ○ | ||||||

| Rooftop garden | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Community garden | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Neighborhood living area | Rooftop garden | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Urban | Community garden | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Others | Urban farming for local food production | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||

| Rental of urban farming equipment | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Category | Reference | Keywords | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before 2011 | [21] | Definition of urban farming concepts, Overseas cases, Legislative measures | Review of relevant laws, Literature review, Survey |

| [22] | Klein Garten, Common vegetable gardens, Operational systems, Institutionalization methods | Overseas case study (Vegetable gardens, system of relevant laws) A case study in Korea (Actuality of utilization, survey) | |

| [23] | Klein Garten, Family park, Regional regeneration policy, Case study of Japan | Literature review Present-condition investigation Interview | |

| [24] | Urban farming status survey, Urban farming categorization, Participant characteristics | Literature review Cluster analysis (logistic regression) | |

| After 2011 | [25] | Participation survey, Value evaluation, Public support | Participation survey Contingent valuation method |

| [26] | Sustainability, Spatial programs, Basic design | Reviews on theories and previous studies Analysis of target-site status Resident survey Design | |

| Recent trends | [27] | Biological control, Companion planting ratio, Green roofs | Experiment Statistical analysis |

| [28] | Garden box, Edible plants, Injection mold, Air pollution | Case study Empirical study | |

| [29] | Urban agriculture, Life cycle assessment, Environmental impacts, Sustainable agriculture | Life cycle assessment Literature search Meta-analysis | |

| [30] | Urban agriculture, Urban agroecology, Ecosystem services, Sustainability | Literature review |

| Interviewee | Answer | Application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fields | Affiliation | Position | ||

| Architectural design | U Urban Planning & Architecture | CEO | “High greenspace rate” and “biotope area rate” should be integrated because they are similar concepts. | Integration |

| M Architects | Director | Convenient transport, represented as, e.g., “distance from the city center, sub-center, and metropolitan connection points”, is important. | Addition | |

| Landscape design | S Landscape | Manager | “Drainage facility” and “security of water” in farming conditions are similar concepts that should be integrated. | Integration |

| C Engineering | Team manager | If a “wind path” is blocked, then crops within apartment complexes may not grow well. | Addition | |

| Agriculture | D.G. Agricultural Technology Center | Rural development officer | If water is not properly circulated within apartment complexes, it not only has a negative impact on the durability of the building, but also results in mold and moss, damaging the aesthetics of the apartments. “Drainage facility” was added. | Addition |

| D.S. Agricultural Technology Center | Rural development officer | Areas vulnerable to “flood damage” should be avoided. | Addition | |

| Urban Agriculture Service Center | Rural development officer | “Revitalization of community” within apartment complexes is important. | Addition | |

| Academia/Research | L Research Institute | Research fellow | “Absence/presence of main roads” and “Vicinity of industrial areas” are similar indicators that should be integrated into “Separation from industrial zones”. “Presence of relevant programs within administrative districts” and “case reports” in the category “technical and management support” should be integrated. | Integration |

| A&U Research Institute | Research fellow | In apartments, repairs are carried out according to the management period after the completion of construction. “Repair time” is more important than “age of apartment building” because satisfying the physical conditions of urban farming in line with the timing of apartment repairs can increase efficiency. | Modification | |

| The presence or absence of “persons in charge of urban farming in apartment maintenance offices” is important. | Addition | |||

| K University | Professor | Regarding resident status, the “proportion of people in their 40s or older” is important, but the “proportion of women” is also crucial. | Modification | |

| Photos of Interviews | ||||

|    | |||

| Fields | Primary Indicators | a | b | c | Final Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a-1 | a-2 | a-3 | b-1 | b-2 | ||||

| A | Absence/presence of main roads (environmental aspect) | ○ | ● | ● | Separation from industrial zones (environmental aspect) | |||

| Vicinity of industrial areas (environmental aspect) | ○ | ○ | ● | |||||

| Distance from the city center, sub-center, and metropolitan connection points | ▲ | △ | △ | High accessibility (traffic) | ||||

| Non-flooded area | ▲ | ▲ | Non-flooded area | |||||

| B | A certain size (number of households) | ○ | ○ | ○ | Size (number of households) | |||

| Age of apartment building | ○ | △ | △ | Apartment repair/renovation time | ||||

| Availability of rooftop use | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | Availability of rooftop use | |||

| Low floor area ratio | ○ | ○ | Low floor area ratio | |||||

| C | Security of water | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | Security of water/Drainage facility | ||

| Drainage facility | ▲ | |||||||

| High sunlight | ○ | ○ | ○ | High sunlight | ||||

| High greenspace rate | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | High greenspace rate/biotope area rate | ||

| Biotope area rate | ○ | ○ | ● | |||||

| Ease of securing cultivation soil | ○ | ○ | Ease of securing cultivation soil | |||||

| Wind path | ▲ | × | × | - | ||||

| D | Presence of related specialized organizations within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | Presence of related specialized organizations within administrative districts | ||

| Presence of related programs within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | Presence of relevant programs within administrative districts (cases) | ||

| Presence of related case reports within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ||||

| Presence of apartment maintenance-office managers | ▲ | ▲ | Presence of apartment maintenance-office managers | |||||

| Presence of urban-farming-related NGOs within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | Presence of urban-farming-related NGOs within administrative districts | |||

| E | Presence of relevant departments within administrative agencies | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | Presence of relevant departments within administrative agencies | ||

| Ordinance for administrative agency support and allocated budget | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | Presence of administrative agency support, ordinance and budget | |||

| Presence of similar support projects within administrative districts | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | Presence of similar support projects within administrative districts | |||

| F | Proportion of people in their 40s or above | ○ | ○ | △ | △ | High proportion of women in their 40s or older | ||

| Low social-activity rate | ○ | ○ | Low social-activity rate | |||||

| Percentage of people with high levels of crop-cultivation experience | ○ | ○ | Percentage of people with high levels of crop-cultivation experience | |||||

| Revitalization of community | ▲ | ▲ | Revitalization of community | |||||

| A: Location condition B: Complex condition | C: Farming condition D: Technical and management support | E: Public funding F: Status of residents | ||||||

| a: Indicator derivation a-1: Literature review a-2: Previous studies a-3: Media articles | b: Indicator categorization b-1: In-depth Interviews b-2: Pilot survey | c: Final indicator selection | ||||||

| Fields | Selection Criteria for Urban Farming Experts | Available Questionnaires | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation | Career | Degree | a | b | c | |

| Architectural design | U Urban Planners & Architects M Architects S Architects & Engineers W Architects | More than 5 years | More than Bachelor’s degree | 20 | 15 | 75% |

| Landscape design | S Landscape Designers C Engineers H Architects | More than 5 years | 20 | 14 | 70% | |

| Agriculture | D.G. Agricultural Technology Center S Agricultural Technology Center D.S. Agricultural Technology Center Urban Agriculture Service Center | More than 7 years | 20 | 12 | 60% | |

| Academia/ Research | National Institute of Agricultural Sciences A&U Research Institute L Research Institute K University | More than 5 years | More than Master’s degree | 20 | 17 | 85% |

| Total | 80 | 58 | 73% | |||

| Fields | Importance | Indicators | Importance | Ranking | Priority Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.089 | A1 | Separation from industrial zones (environmental aspect) | 0.039 | 12 |  |

| A2 | High accessibility (traffic) | 0.026 | 17 |  | ||

| A3 | Non-flooded area | 0.024 | 18 |  | ||

| B | 0.126 | B1 | Size (number of households) | 0.024 | 18 |  |

| B2 | Apartment repair/renovation time | 0.028 | 16 |  | ||

| B3 | Availability of rooftop use | 0.058 | 7 |  | ||

| B4 | Low floor area ratio | 0.016 | 22 |  | ||

| C | 0.131 | C1 | Security of water/Drainage facility | 0.032 | 15 |  |

| C2 | High sunlight | 0.035 | 13 |  | ||

| C3 | High greenspace rate/Biotope area rate | 0.041 | 11 |  | ||

| C4 | Ease of securing cultivation soil | 0.023 | 20 |  | ||

| D | 0.219 | D1 | Presence of related specialized organizations within administrative districts | 0.045 | 10 |  |

| D2 | Presence of relevant programs within administrative districts (cases) | 0.065 | 5 |  | ||

| D3 | Presence of apartment maintenance office managers | 0.050 | 9 |  | ||

| D4 | Presence of urban-farming-related NGOs within administrative districts | 0.059 | 6 |  | ||

| E | 0.249 | E1 | Presence of relevant departments within administrative agencies | 0.067 | 4 |  |

| E2 | Presence of administrative agency support ordinance and budget | 0.108 | 1 |  | ||

| E3 | Presence of similar support projects within administrative districts | 0.074 | 3 |  | ||

| F | 0.186 | F1 | High proportion of women in their 40s or above | 0.019 | 21 |  |

| F2 | Low social activity rate | 0.033 | 14 |  | ||

| F3 | Ratio of people with high crop cultivation experience | 0.057 | 8 |  | ||

| F4 | Revitalization of community | 0.077 | 2 |  | ||

| 6 fields | 1.000 | 22 indicators | 1.000 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.; Sim, H. Study of Plans to Ensure the Sustainability of Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416797

Kim D, Sim H. Study of Plans to Ensure the Sustainability of Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416797

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Donghyun, and Hyunnam Sim. 2023. "Study of Plans to Ensure the Sustainability of Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416797

APA StyleKim, D., & Sim, H. (2023). Study of Plans to Ensure the Sustainability of Urban Farming in Apartment Complexes. Sustainability, 15(24), 16797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416797