The Experiences of Layoff Survivors: Navigating Organizational Justice in Times of Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1.

- What are the views of surviving employees regarding the fairness of layoff?

- RQ2.

- What are the challenges in a post-layoff environment perceived by surviving employees?

- RQ3.

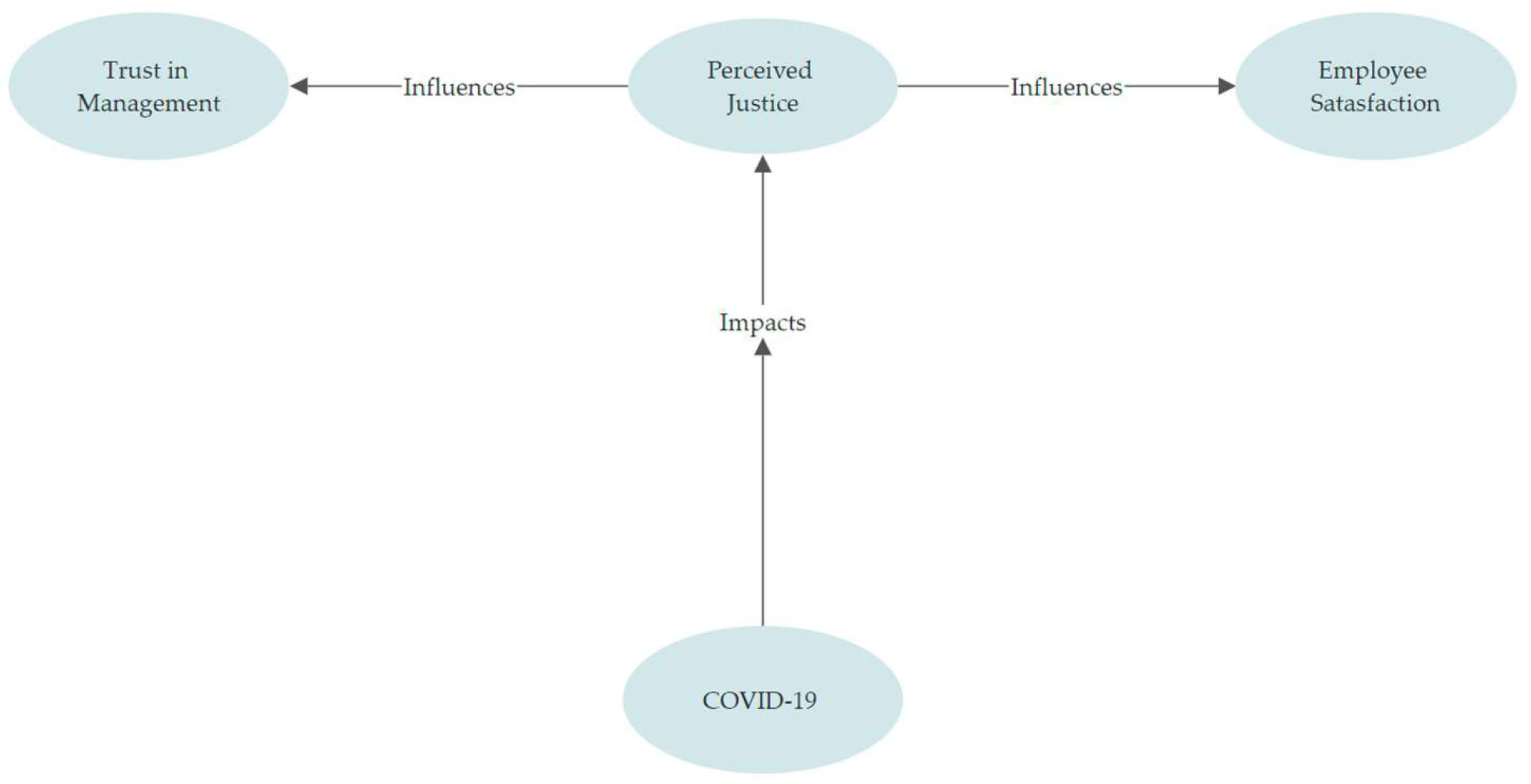

- How do layoffs impact job satisfaction and trust in management, as perceived by surviving employees?

2. COVID-19 and the Hospitality Sector

3. COVID-19 Layoffs at Airbnb

4. Literature Review and Research Questions

4.1. Organizational Justice and Surviving Employees

4.2. Research Questions

5. Methods

5.1. Participants

5.2. Instruments and Procedures

5.3. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Broader Business Context

6.2. Challenges Faced by Surviving Employees

“I’m convinced the company handled the layoffs with a great deal of humaneness, unlike some organizations that employ more callous methods. Even though I wasn’t directly affected by layoffs, I observed how considerately the company dealt with those who were. Many companies announce layoffs via impersonal channels like emails or direct supervisors, often making for an abrupt and uncomfortable transition. Airbnb, on the other hand, was thoughtful even about the emotional toll on supervisors. Rather than having direct supervisors deliver the unfortunate news, Airbnb arranged for it to be done by a manager who wasn’t in the direct reporting line. This approach could lessen the emotional strain on everyone involved. In addition, laid-off employees were allowed to keep their company-issued MacBooks and cell phones. Most commendable, perhaps, was the creation of a Talent Directory on the corporate website to aid the departed employees in their job search, alongside other outreach efforts aimed at potential employers. This led to a less bitter exit experience for those who had to leave”.

6.3. Leadership Communication

7. Discussion

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

7.2.1. Workload Prioritization

7.2.2. Regular Check-Ins

7.2.3. Recognition of Survivors’ Struggles

7.2.4. Training and Development

7.2.5. Reaffirming the Purpose and Vision of the Company

7.3. Limitations

7.4. Future Research Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

- Can you describe your personal experience during the company’s layoffs, including your thoughts and feelings at that time?

- How did you interpret the reasons and motivations behind the layoffs as they were communicated to you?

- Can you share any moments or actions that particularly stood out for you?

- Did you get a sense of how decisions were being made about who was laid off?

- In response to the layoffs, how did you make sense of the situation and adapt to the changes in your work and life?

- Can you share any personal strategies or coping mechanisms you employed to navigate the challenges brought on by the layoffs?

- Can you describe any new pressures or responsibilities you’ve noticed since the layoffs?

- How does this impact your daily work-life balance?

- Can you talk about how your feelings toward your job have changed since the layoffs?

- Are there specific things that have made your work more or less enjoyable?

- How do you subjectively assess your job satisfaction and overall well-being now, compared to before the layoffs?

- What factors, both within and outside of work, do you believe contribute most to your sense of well-being in the current context?

- Has your view of the management team changed since the layoffs? In what ways?

- Are there things that could be done to rebuild or strengthen that trust?

- From your perspective, how has the company’s culture influenced your experiences and reactions during and after the layoffs?

- Can you share instances where trust or mistrust in the organization’s leadership played a role in your perceptions and actions?

- If so, can you describe how it has impacted you?

- Have your values, priorities, or perspectives on work and career changed in any way since the layoffs?

- Looking ahead, what are your hopes or aspirations for the future within the organization or beyond?

References

- Alonso, A.D.; Kok, S.K.; Bressan, A.; O’Shea, M.; Sakellarios, N.; Koresis, A.; Solis, M.A.B.; Santoni, L.J. COVID-19, Aftermath, Impacts, and Hospitality Firms: An International Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Thompson, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Hospitality Sector: Challenges and Strategies for Recovery. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). Available online: https://wttc.org/news-article/coronavirus-puts-up-to-50-million-travel-and-tourism-jobs-at-risk-says-wttc (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Baum, T.; Hai, N.T.T. Hospitality, Tourism, Human Rights and the Impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-L.; McAleer, M.; Ramos, V. A Charter for Sustainable Tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F. Downsizing: What do we know? What have we learned? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1993, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dial, J.; Murphy, K.J. Incentives, Downsizing, and Value Creation at General Dynamics. J. Financ. Econ. 1995, 37, 261–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnigle, P.; Lavelle, J.; Monaghan, S. Weathering the Storm? Multinational Companies and Human Resource Management through the Global Financial Crisis. Int. J. Manpow. 2013, 34, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, H.; MacKenzie, R.; Forde, C. HRM and Performance: The Vulnerability of Soft HRM Practices during Recession and Retrenchment. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, P.; De Cieri, H.; Minbaeva, D.; Verbeke, A.; Zimmermann, A. International HRM Insights for Navigating the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Future Research and Practice. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Delage, C.; Labib, N.; Gault, G. The Survivor Syndrome: Aftermath of Downsizing. Career Dev. Int. 1997, 2, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.; Chau, V.S.; Cox, J. Managing the Survivor Syndrome as Scenario Planning Methodology…and It Matters! Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.; Anderson, R. Survivor Syndrome in the Hospitality Industry: A Case of Unintended Consequences. J. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 45, 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Hong, S.; Lee, B.G. Is There a Right Way to Lay Off Employees in Times of Crisis?: The Role of Organizational Justice in the Case of Airbnb. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, K.; Breslin, D. The COVID-19 Pandemic: What Can We Learn from Past Research in Organizations and Management? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.D.; Dasborough, M.T.; Gregg, H.R.; Xu, C.; Deen, C.M.; He, Y.; Restubog, S.L.D. Traversing the Storm: An Interdisciplinary Review of Crisis Leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2022, 34, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.; Anseel, F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Bamberger, P.; Bapuji, H.; Bhave, D.P.; Choi, V.K.; et al. COVID-19 and the Workplace: Implications, Issues, and Insights for Future Research and Action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Effect and Survival Strategy for Businesses. J. Econ. Bus. 2020, 3, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mansour, J.F.; Al-Ajmi, S.A. Coronavirus ‘COVID-19’—Supply Chain Disruption and Implications for Strategy, Economy, and Management. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. (JAFEB) 2020, 7, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, M.; Guenther, C.; Kritikos, A.S.; Thurik, R. Economic Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Entrepreneurship and Small Businesses. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibn-Mohammed, T.; Mustapha, K.B.; Godsell, J.; Adamu, Z.; Babatunde, K.A.; Akintade, D.D.; Acquaye, A.; Fujii, H.; Ndiaye, M.M.; Yamoah, F.A.; et al. A Critical Analysis of the Impacts of COVID-19 on the Global Economy and Ecosystems and Opportunities for Circular Economy Strategies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, L.J. Surf Tourism in Uncertain Times: Resident Perspectives on the Sustainability Implications of COVID-19. Societies 2021, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D.V.; Truong, T.T.K.; Duong, L.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Dao, G.V.H.; Dao, C.N. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impacts on Tourism Business in a Developing City: Insight from Vietnam. Economies 2021, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, F.R.; Omer, T.; Carley, K.M. COVID-19: Network Analysis of Effects on Organizational Staffing. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Burhan, M.; Salam, M.T.; Abou Hamdan, O.; Tariq, H. Crisis Management in the Hospitality Sector SMEs in Pakistan during COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morar, C.; Tiba, A.; Basarin, B.; Vujičić, M.; Valjarević, A.; Niemets, L.; Gessert, A.; Jovanovic, T.; Drugas, M.; Grama, V.; et al. Predictors of Changes in Travel Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Tourists’ Personalities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, M.; Johnson, P. Navigating Uncertainty: Hospitality Industry’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104315. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.; Young, T. A Crisis Unlike Any Other: Exploring the Challenges Faced by the Hospitality Industry during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102868. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, J.; Walters, K. The Importance of Training and Development in Employee Performance and Evaluation. World Wide J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2017, 3, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, L.; Lewis, G. The Human Side of Hospitality Management during a Pandemic: Exploring Emotional Labor and Well-Being. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 111, 102913. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A.; Scott, D. Employee Resilience in the Hospitality Sector amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2022, 95, 587–602. [Google Scholar]

- Boros, L.; Dudás, G.; Kovalcsik, T. The Effects of COVID-19 on Airbnb. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2020, 69, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurieff, K. Airbnb Is Laying Off about 25% of Its Employees. 2020. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/05/05/tech/airbnb-layoffs/index.html (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Airbnb’s CEO Shows All Businesses How to Conduct Layoffs. Available online: https://www.inc.com/suzanne-lucas/airbnbs-ceo-shows-all-businesses-how-to-conduct-layoffs.html (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Airbnb Lays Off 25% of Its Employees: CEO Brian Chesky Gives a Master Class in Empathy and Compassion. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2020/05/06/airbnb-lays-off-25-of-its-employees-ceo-brian-chesky-gives-a-master-class-in-empathy-and-compassion/ (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Hong, S.; Lee, S. Adaptive Governance and Decentralization: Evidence from Regulation of the Sharing Economy in Multi-Level Governance. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, S. Adaptive Governance, Status Quo Bias, and Political Competition: Why the Sharing Economy Is Welcome in Some Cities but Not in Others. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, S. Sharing Economy and Government. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Chen, H. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Airbnb’s Business Performance: An Empirical Study. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104272. [Google Scholar]

- Airbnb Lost Millions in Revenue due to The Coronavirus, IPO Filing Reveals. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2020/11/16/21570416/airbnb-coronavirus-pandemic-travel-hospitality (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Tu, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, H.-J. COVID-19-Induced Layoff, Survivors’ COVID-19-Related Stress and Performance in Hospitality Industry: The Moderating Role of Social Support. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisetsri, W.; Lourens, M.E.; Cavaliere, L.P.L.; Chakravarthi, M.K.; Nijhawan, G.; Nuhmani, S.; Rajest, S.S.; Regin, R. The Effect of Layoffs on the Performance of Survivors at Healthcare Organizations. Nat. Volatiles Essent. Oils J. 2021, 8, 5574–5593. [Google Scholar]

- Turn Departing Employees into Loyal Alumni. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/03/turn-departing-employees-into-loyal-alumni (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- ‘Allow People to Leave the Company with Dignity’: How Airbnb CEO’s Pandemic Layoffs Stand in Stark Contrast to Meta and Twitter. Available online: https://fortune.com/2022/11/18/tech-layoffs-airbnb-versus-meta-twitter/ (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- The 21st-Century Corporation: A Conversation with Brian Chesky of Airbnb | McKinsey. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-21st-century-corporation-a-conversation-with-brian-chesky-of-airbnb (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Greenberg, J. Organizational Justice: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. J. Manag. 1990, 16, 399–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. The Social Side of Fairness: Interpersonal and Informational Classes of Organizational Justice. In Justice in the Workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management; Cropanzano, R.M., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Hill, E.T.; De Cremer, D. Forever Focused on Fairness: 75 Years of Organizational Justice in Personnel Psychology. Pers. Psychol. 2023, 76, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outlaw, R.; Colquitt, J.A.; Baer, M.D.; Sessions, H. How Fair versus How Long: An Integrative Theory-based Examination of Procedural Justice and Procedural Timeliness. Pers. Psychol. 2019, 72, 361–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Lowman, G.H.; Harms, P. Justice for the Crowd: Organizational Justice and Turnover in Crowd-Based Labor. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, H.K.; Aaron Johnson, J.; Martin, J.K.; Roman, P.M. Downsizing Survival: The Experience of Work and Organizational Commitment. Sociol. Inq. 2003, 73, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayton, B.A.; Yalabik, Z.Y. Work Engagement, Psychological Contract Breach and Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2382–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.G.; Nyberg, A.J.; Wright, P.M.; McMackin, J. Leading through Paradox in a COVID-19 World: Human Resources Comes of Age. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korman, K.; Mujtaba, B.G. Corporate Responses to COVID-19 Layoffs in North America and the Role of Human Resources Departments. Rep. Glob. Health Res. 2020, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe, É.; Vandenberghe, C.; Panaccio, A. Organizational Commitment, Organization-Based Self-Esteem, Emotional Exhaustion and Turnover: A Conservation of Resources Perspective. Hum. Relat. 2011, 64, 1609–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, B.G.; Senathip, T. Layoffs and Downsizing Implications for the Leadership Role of Human Resources. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2020, 13, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumpi, D. Rethinking the Strategic Management of Human Resources: Lessons Learned from COVID-19 and the Way Forward in Building Resilience. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2021, 31, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in Social Exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1965; Volume 2, pp. 267–299. ISBN 9780080567167. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, K.M.; Weathington, B.L. The Moderating Role of the Distributive Justice Cognitions in the Relationship between Job Insecurity and Withdrawal. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 2185–2209. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Tur, V.; Peiró, J.M.; Ramos, J.; Moliner, C. Justice Perceptions as Predictors of Customer Satisfaction: The Impact of Distributive, Procedural, and Interactional Justice 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W. Reshuffled Stratification Order and Perceptions of Distributive Justice and Social Problems in Urban China. In Social Inequality in China; World Scientific: Singapore, 2023; pp. 603–630. [Google Scholar]

- Clay-Warner, J.; Hegtvedt, K.A.; Roman, P. Procedural Justice, Distributive Justice: How Experiences with Downsizing Condition Their Impact on Organizational Commitment. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2005, 68, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H. Framing Effects, Procedural Fairness, and the Nonprofit Managers’ Reactions to Job Layoffs in Response to the Economic Shock of the COVID-19 Crisis. Voluntas Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2022, 33, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konovsky, M.A.; Brockner, J. Managing Victim and Survivor Layoff Reactions: A Procedural Justice Perspective. In Justice in the Workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management; Cropanzano, R.M., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bies, R.J.; Moag, J.S. Interactional Justice: Communication Criteria of Fairness. In Research on Negotiation in Organizations; Lewicki, R.J., Sheppard, B.H., Bazerman, M.H., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.L.H.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the Millennium: A Meta-Analytic Review of 25 Years of Organizational Justice Research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J. Making Sense of Procedural Fairness: How High Procedural Fairness Can Reduce or Heighten the Influence of Outcome Favorability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Folger, R. Retaliation in the Workplace: The Roles of Distributive, Procedural, and Interactional Justice. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Greenberg, J. The Impact of Layoffs on Survivors: An Organizational Justice Perspective. In Applied Social Psychology and Organizational Settings; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 45–75. ISBN 1-315-72837-0. [Google Scholar]

- Natunann, S.E.; Bies, R.J.; Martin, C.L. The Roles of Organizational Support and Justice during a Layoff. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 1995; Volume 1995, pp. 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dierendonck, D.; Jacobs, G. Survivors and Victims, a Meta-analytical Review of Fairness and Organizational Commitment after Downsizing. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Gavin, M.B.; Bunce, L.W. Perceived Fairness of Layoffs among Individuals Who Have Been Laid off: A Longitudinal Study. Pers. Psychol. 1999, 52, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovsky, M.A. Understanding Procedural Justice and Its Impact on Business Organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, A.; Skarlicki, D.P. Personality and Perceived Justice as Predictors of Survivors’ Reactions Following Downsizing. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 1306–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, S.E.; Bennett, N.; Bies, R.J.; Martin, C.L. Laid off, but Still Loyal: The Influence of Perceived Justice and Organizational Support. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 1998, 9, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.S.; Karau, S.J. Preserving Employee Dignity during the Termination Interview: An Empirical Examination. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharahsheh, H.H.; Pius, A. A Review of Key Paradigms: Positivism VS Interpretivism. Glob. Acad. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 2, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1-5063-8671-7. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1-5063-3019-3. [Google Scholar]

- McChesney, K.; Aldridge, J. Weaving an Interpretivist Stance throughout Mixed Methods Research. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2019, 42, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.T.M. Qualitative Approach to Research a Review of Advantages and Disadvantages of Three Paradigms: Positivism, Interpretivism and Critical Inquiry; University of Adelaide: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 4th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2007; Volume 6, pp. 1–268. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.; Thornhill, A. Organisational Justice, Trust and the Management of Change: An Exploration. Pers. Rev. 2003, 32, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianson, M.K.; Barton, M.A. Sensemaking in the Time of COVID-19. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S.; Sonenshein, S. Sensemaking in Crisis and Change: Inspiration and Insights from Weick (1988). J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 551–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.; Tsoukas, H. Making Sense of the Sensemaking Perspective: Its Constituents, Limitations, and Opportunities for Further Development. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, S6–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderifar, M.; Goli, H.; Ghaljaie, F. Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 2017, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. Pros and Cons of Different Sampling Techniques. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2017, 3, 749–752. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W.; Donnelly, J. Qualitative and Unobtrusive Measures. In The Research Methods Knowledge Base; Atomic Dog: Mason, OH, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic Methodological Review: Developing a Framework for a Qualitative Semi-structured Interview Guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 1-4522-8586-1. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Qualitative Research. In Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hollweck, T.; Robert, K.Y. Case Study Research Design and Methods. Can. J. Program Eval. 2015, 30, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, W.; Brown, A. Working with Qualitative Data; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 1-4462-0249-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M. Analytical Methods Used in Contemporary IS Research. In Information Systems Research: Foundations, Design and Theory; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- King, N.; Horrocks, C. An Introduction to Interview Data Analysis. In Interviews in Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 142, p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Bergin, T. An Introduction to Data Analysis: Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–296. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 1-5297-5599-9. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, M.K.B.; Bin Amir, M.Z. COVID-19 Pandemic: Socio-Economic Response, Recovery and Reconstruction Policies on Major Global Sectors. 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3629670 (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Gulyas, A.; Pytka, K. The Consequences of the COVID-19 Job Losses: Who Will Suffer Most and by How Much? Covid Econ. 2020, 1, 70–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bilotta, I.; Cheng, S.K.; Ng, L.C.; Corrington, A.R.; Watson, I.; King, E.B.; Hebl, M.R. Softening the Blow: Incorporating Employee Perceptions of Justice into Best Practices for Layoffs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. Policy 2020, 6, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Zacher, H. The COVID-19 Generation”: A Cautionary Tale of the Long-Term Effects of Layoffs. Work Aging Retire. 2020, 6, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. COVID-19 Is Also a Reallocation Shock; Brookings Papers on Economic Activity; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 163–237. [Google Scholar]

- Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Meyer, B.H. COVID-19 Is a Persistent Reallocation Shock. In AEA Papers and Proceedings; American Economic Association: Nashville, TN, USA, 2021; Volume 111, pp. 287–291. [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker, E.W.; Meyer, P.B.; Piacentini, J.; Schultz, M.; Sveikauskas, L. Employment Recovery in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mon. Lab. Rev. 2020, 143, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Horst, M.; Seo, H. Employment Insecurity in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Who Are the Most at Risk and Why? Econ. Ind. Democr. 2020, 42, 686–701. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner, J. Managing the Effects of Layoffs on Survivors. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1992, 34, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noer, D.M. Healing the Wounds: Overcoming the Trauma of Layoffs and Revitalizing Downsized Organizations; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Rodell, J.B. Measuring Justice and Fairness. In The Oxford Handbook of Justice in the Workplace; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner, J.; Wiesenfeld, B.M. An Integrative Framework for Explaining Reactions to Decisions: Interactive Effects of Outcomes and Procedures. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 120, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Blader, S.L. The Group Engagement Model: Procedural Justice, Social Identity, and Cooperative Behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 7, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macky, K.A. Organisational Downsizing and Redundancies: The New Zealand Workers Experience. N. Z. J. Employ. Relat. 2004, 29, 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner, J.; Spreitzer, G.; Mishra, A.; Hochwarter, W.; Pepper, L.; Weinberg, J. Perceived Control as an Antidote to the Negative Effects of Layoffs on Survivors’ Organizational Commitment and Job Performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Grover, S.; Reed, T.; Dewitt, R.L. Layoffs, Job Insecurity, and Survivors’ Work Effort: Evidence of an Inverted-U Relationship. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 35, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hammali, M.A.; Habtoor, N.; Heng, W.H. Effect of Forced Downsizing Strategies on Employees’ Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Manag. Hum. Sci. 2021, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, G.; Estabrooks, C.A. The Effects of Hospital Restructuring That Included Layoffs on Individual Nurses Who Remained Employed: A Systematic Review of Impact. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2003, 23, 8–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.I.; Ahmad, M.; Saif, M.I.; Safwan, M.N. Relationship of Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and Layoff Survivor’s Productivity. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2010, 2, 200–211. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. Trust in Leadership: Meta-Analytic Findings and Implications for Research and Practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Mishra, A.K. To Stay or to Go: Voluntary Survivor Turnover Following an Organizational Downsizing. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 707–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Kim, D.H. Factors Affecting Stayers’ Job Satisfaction in Response to a Coworker Who Departs for a Better Job. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 1659–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The Impact of Job Crafting on Job Demands, Job Resources, and Well-Being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, D.E.; Cropanzano, R. The Mediating Effects of Social Exchange Relationships in Predicting Workplace Outcomes from Multifoci Organizational Justice. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2002, 89, 925–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costen, W.M.; Salazar, J. The Impact of Training and Development on Employee Job Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Intent to Stay in the Lodging Industry. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 10, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, A.M.; Murphy, C.; Clark, J.R. A (Blurry) Vision of the Future: How Leader Rhetoric about Ultimate Goals Influences Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1544–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Objective | Research Questions | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|

| Understand how COVID-19 layoffs affected employee perceptions of fairness at Airbnb | What are the views of surviving employees regarding the fairness of layoff processes? | H1: Layoff survivors perceive a significant decline in organizational fairness due to COVID-19 layoffs. |

| Identify the challenges faced by employees who survived the layoffs | What are the challenges in a post-layoff environment perceived by surviving em-ployees? | H2: Surviving employees face multiple challenges, including increased workload and survivor syndrome. |

| Assess the impact of layoffs on job satisfaction and trust in management | How do layoffs impact job satisfaction and trust in management from the perspective of surviving employees? | H3: Layoffs negatively impact job satisfaction and trust in management among surviving employees. |

| Participants | Age | Gender | Marital Status | Years in Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | 37 | Female | Single | 12 |

| Participant 2 | 35 | Male | Married | 10 |

| Participant 3 | 43 | Male | Married | 18 |

| Participant 4 | 43 | Male | Married | 15 |

| Participant 5 | 35 | Male | Married | 10 |

| Participant 6 | 35 | Female | Single | 10 |

| Participant 7 | 41 | Female | Married | 14 |

| Participant 8 | 31 | Female | Single | 7 |

| Participant 9 | 30 | Male | Single | 5 |

| Participant 10 | 37 | Female | Single | 11 |

| Participant 11 | 33 | Male | Single | 8 |

| Participant 12 | 31 | Female | Married | 6 |

| Participant 13 | 32 | Female | Single | 7 |

| Participant 14 | 33 | Female | Single | 8 |

| Participant 15 | 31 | Male | Married | 6 |

| Research Inquiry | Illustrative Quotes | First-Order Codes | Creation of Conceptual Categories through Code Consolidation | Main Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding the Layoff Experience | I somewhat expected the layoffs due to my role in vendor and contractor management. They were impacted early on, and I saw a significant reduction in contractors. I thought if the economy didn’t recover soon, Airbnb employees would also be affected. So, the news wasn’t that surprising. (Participant 1) | Predictability and Awareness | Prediction of Layoff | Unique Circumstances Brought by COVID-19 |

| I believed there could have been better alternatives than layoffs, like salary cuts. However, the industry’s downturn was evident. While I’m sad, I understand the need for drastic measures. (Participant 7) | Understanding and Acceptance | Prediction of Layoff | ||

| The timing of the layoff seemed predictable. The week before, all contractors were let go globally. As employees, we thought, if contractors are gone, we might be next. There was fear and nervousness. (Participant 9) | Predictability and Fear | Prediction of Layoff | ||

| Post-Layoff Challenges and Coping Mechanisms | It was difficult. Not even knowing who the victims were, I still feel bad about their situation, and it also caused me significant personal stress. Some people I used to work closely with were directly impacted by the layoffs, and I had a hard time watching their situation right next to mine. I think the hardest part was witnessing my closest colleagues losing their jobs suddenly. There were no clear criteria regarding who was laid off. It wasn’t a matter of people with longer or shorter tenure being laid off; it seemed more random. Even individuals with over 5 years of tenure were laid off suddenly. (Participant 13) | Emotional Stress, Uncertainty, Random Layoffs | Uncertainty | Survivor Syndrome |

| What I felt was that it’s an incredibly heart-wrenching process to let go of people who were closer than family. I’ve been crying for the past three weeks and have been mentally unstable. My top priority was to help the victims find new jobs as soon as possible. However, on the other hand, I learned a lot during the process. Would I have been able to make such a decision if I were the CEO? So, I think this is why many people, including HR managers, also view the recent layoffs as a best practice. It was an inevitable decision made in a difficult situation, but, you know, business has its ups and downs. I really learned a great deal through the recent layoffs about how to handle a difficult situation in the least painful way (Participant 4) | Emotional Stress, Learning Experience, Best Practice | Emotional Stress | ||

| The layoff occurred after COVID, during a period when we saw a surge in the number of projects executed on a global scale. We became even busier than before, and the restructuring made things worse by significantly increasing our workload. That’s what I can say in terms of job satisfaction. Not only has the atmosphere become more tense, but the actual workload has also skyrocketed. This increase is due to the layoffs, but it’s also because HQ initiated numerous projects in response to the COVID situation. (Participant 2) | Increased Workload, Tension, COVID-19 Response | Increased Workload | Increased Workload | |

| After the layoffs, the workload increased significantly, and I can’t say I’m happy about the situation. I believe this has been the most stressful part. (Participant 5) | Workload Stress | Increased Workload | ||

| At first, we were all deeply affected by the layoffs but tried to maintain our spirits and give our best despite the increased workload. However, I began to perceive this as unjust for the survivors. While I do sympathize with the victims, the workload for the survivors has surged dramatically, and it feels like we’re being pushed to our limits to compensate for the manpower loss and cost-cutting measures. This became one of my primary concerns about the current situation. (Participant 10) | Injustice, Sympathy, Workload Concerns | Increased Workload | ||

| After the layoffs, my workload increased significantly, and I no longer see a clear vision for this team. These are the two most significant changes. Additionally, I’m still uncertain about whether I should continue with the company or consider other options. (Participant 12) | Increased Workload, Uncertainty, Job Continuation | Increased Workload | ||

| We have offices across the globe, including Europe, the US, and Asia. The US was hit the hardest, while Asia was relatively less affected. Even though the company assured us that there wouldn’t be any more layoffs after the initial wave that saw 25% of the entire workforce being let go, employees had different concerns. We constantly felt anxious and worried that there might be another round of layoffs unless the COVID situation stabilized, and that those who had survived the first wave could also be affected at any moment. I felt uneasy every time I received an email in the morning, and for quite some time, I actively searched for news about Airbnb on the internet. Among the survivors, there were various opinions, and we shared information we had gathered from different sources. (Participant 11) | Anxiety, Predictability, Information Sharing | Information Sharing | Information Sharing | |

| I believe there are two distinct types of stress. One is the emotional strain stemming from the loss of my colleagues, while the other is work-related stress resulting from the increased workload caused by a smaller workforce. I realized that there’s little I can do about emotional stress, so I decided to accept reality, and this approach significantly helped alleviate it. Regarding work-related stress, fortunately, the company was willing to discuss what kind of additional support we needed after the layoffs, so the impact wasn’t as significant as initially feared. Nevertheless, it became each team’s responsibility to make things work, and I imagine the leadership team must have been under tremendous stress, likely working day and night. I heard that some individuals even had to work on weekends to optimize the workload under the new system. (Participant 15) | Emotional Stress, Work-Related Stress, Leadership Support | Leadership Support | Open Communication by Leadership | |

| Impacts on Job Satisfaction and Trust in Management | CEO said that it was no one’s fault. He also said that when the company recovers from the situation, he wants to bring back the people who were impacted first. The company made a talent directory and made people voluntarily upload their resumes and made sure that the information is shared with many recruiters. Everyone, including the impacted and survivors share the directory through LinkedIn. There were many victims in my team; for instance, some were people that were ranked number one in Asia in terms of performance. Just by that, we can see that performance was not the main criterion when deciding who would be impacted. So, the company really provided good support in supporting these people to find new jobs. The package was also generous. The company allowed the victims to keep the company computers and cell phones. The remaining recruiters are also providing career coaching and resume building services to the impacted. (Participant 4) | CEO Communication, Support, Generous Package | Organizational Support for victims | |

| Airbnb did not simply lay off employees but kindly held one-on-one sessions with each victim, so the company told us that if you received a Google Calendar invite, you would most likely be laid off. This kept us from focusing on work all day long, and I remember looking at the Google Calendar all day. In the big picture, I think this is the best way the company could deal with the situation. Because the layoff started off from an extremely understandable background, I think no one could really argue against the necessity of a layoff from the company’s perspective. Although I am not a victim, I would like to say that the company’s approach to each victim was actually commendable. On top of that, I heard that the severance package was also quite generous. Overall, I think Airbnb really cared about the victims compared to other companies. (Participant 9) | Communication, Layoff Approach, Generosity | Open Communication | ||

| I am sure that the company treated us with dignity. Some companies take a really inhumane approach in laying people off. However, Airbnb treated everyone in a very humanitarian manner. Although I was not laid off, the way the company treated people that were impacted was so humane. I heard that some companies simply notify the layoff through email or simply make the direct supervisor hold one-on-one sessions to notify the victim to stop coming to work from the next week. However, Airbnb even put into consideration how the supervisor would feel. Just think about how it would feel when a supervisor has to notify his/her team member of the bad news. Airbnb structured the process in a way that an indirect supervisor would be the one conveying the news. So, a manager who is not a direct reporting line of the impacted would notify the victim through a video conference. I believe this can minimize the pain in the process. (Participant 5) | Humanitarian Approach, Layoff Notification | Communication | ||

| The CEO reported to employees on the situation on a weekly basis, and everyone was aware that the travel industry was in a downturn and that layoffs were inevitable. People to be laid off were selected not based on work performance but based on the assessment of the need of the company for a specific function after the COVID situation. If the function is no longer in need after the situation, people were cut off from the team. (Participant 3) | Layoff Rationale, Functional Assessment | Regular Check-in | Regular Check-in | |

| Although not explicitly announced, the leadership team understood that it was a hard time for everyone, so they gave us some time to mourn. I think it was also communicated well because the leadership team told us not to focus too much on delivering work on time. They also told us to try to stay true to what’s immediately in front of us and to relax. The company gave us one extra day off called the wellness holiday. Even before the layoff, the CEO held virtual check-in sessions with all the employees and told us that he is also extremely sad about the situation and that there won’t be additional layoffs going forward. I think that kind of effort helped us in focusing and getting back to work. I personally did not feel an extreme amount of tension. Of course, there were discussions around the fear that I could be laid off next, but after the latest check-in by the CEO, everyone was somewhat relieved. (Participant 15) | Leadership Support, Company Efforts, Relief | Regular Check-in |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Hong, S.; Shin, W.-Y.; Lee, B.G. The Experiences of Layoff Survivors: Navigating Organizational Justice in Times of Crisis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416717

Lee S, Hong S, Shin W-Y, Lee BG. The Experiences of Layoff Survivors: Navigating Organizational Justice in Times of Crisis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416717

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sanghyun, Sounman Hong, Won-Yong Shin, and Bong Gyou Lee. 2023. "The Experiences of Layoff Survivors: Navigating Organizational Justice in Times of Crisis" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416717

APA StyleLee, S., Hong, S., Shin, W.-Y., & Lee, B. G. (2023). The Experiences of Layoff Survivors: Navigating Organizational Justice in Times of Crisis. Sustainability, 15(24), 16717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416717