1. Introduction

Modernist architecture of the twentieth century, which significantly shapes the identity of cities, underwent adaptation, evolution, and transformation influenced by local conditions and contexts. Hence, a discussion about modernist architectural heritage necessitates an appreciation of both universal and local guidelines. This study conducts a comparative analysis to examine how modernism was embraced and evolved within local contexts. The analysis centres on selected multi-storey houses, housing estates, and urban layouts constructed during the latter half of the twentieth century in two industrial, high-density regions: Izmir, Turkey, and Tychy, in the Upper Silesia Agglomeration, Poland.

These chosen examples exemplify how diverse local contexts could impact the reception of global modernism. Izmir’s context was characterised by political, social, economic, and lifestyle changes commencing in 1923, while Tychy’s context was marked by the communist and inter-war periods. The research problem underscores the significance of examining modernism under distinct local conditions and highlighting the disparities and commonalities in the application of universal principles within local contexts.

The research aimed to address the following questions:

What are the characteristics of twentieth-century housing estate architecture within the modern movement? How have these characteristics been influenced by local contexts?

How can housing architecture be effectively compared and analysed in terms of its various aspects? What are the commonalities and distinctions observed in local contexts?

This study sought to provide insights into these questions by examining the housing estate architecture of the modern movement in both Izmir and Tychy, exploring how universal principles were adapted and modified within each unique local context.

The research presented in this study serves as a pilot study with the aim of developing a methodology for future comparative analyses. It involves the comparison of specific cases and integrates theoretical concepts with collected data to draw conclusions. The analysis examines the similarities and differences between the selected representative cases using a shared theoretical framework, focusing on both urban and architectural aspects within their respective local contexts. By identifying the commonalities and distinctions in these conditions, this study highlights how modernist architecture takes on unique characteristics within local contexts. This comparative approach contributes to the existing literature on the subject and proposes a systematic method for organising information in future studies.

Over the years, numerous studies have delved into various aspects of housing estates constructed in the second half of the 20th century. The existing literature has explored their history, emergence, development, transformations, issues, and renewal programmes, continuously expanding the body of knowledge in this field. However, this study contributes to the existing understanding of housing estates by emphasising the following aspects:

It underscores the significance of considering local contexts within the broader international discourse on this topic. This contribution aims to reveal, define, and safeguard the values associated with the modernist heritage of housing estates, offering a more comprehensive perspective.

It introduces insights from the two case studies, Izmir and Tychy, which have not been extensively compared previously. This comparative analysis offers a fresh perspective on the subject.

By comparing two distinct local contexts and framing them within a global dimension, this proposed analysis sheds light on the architectural and urban values of housing estates, providing a broader understanding of the topic. It enables sustainable development of architectural heritage values by promoting knowledge in a systematic approach.

In summary, this study enriches the existing knowledge on housing estates by considering local contexts, offering novel insights from comparative case studies, and presenting a global perspective on the subject.

The present study comprises three main steps:

Theoretical background: This step involves providing the theoretical foundation for the subject matter.

Methods and materials: This section details the research methodology, including information about the case study, the analytical tools used, and the research procedure.

Comparative analysis in local contexts: The final step involves conducting the comparative analysis of the selected case studies.

The research scope encompasses a comprehensive review of the existing literature, archival research, the selection of relevant time periods, identification of case study sites, on-site observations, photography, documentation, and the comparative analysis of these local examples.

Comparative analysis is posited as an effective method for grasping housing transformations. By centring on the latter half of the twentieth century, this study offers a more structured framework for delving into architectural history.

2. Theoretical Background of Study

Modern-period housing and housing estates have been widely covered in the literature in a significant number of scientific studies and publications in different contexts. They are still a diverse resource that needs detailed research.

The literature addresses housing from perspectives of development, transformations, issues, and renewal programmes. Notably:

Hess et al. [

1] edited a book on the creation, social dynamics, and physical compositions of large European housing estates, detailing policy responses to challenges across 14 case studies.

Dekker et al. [

2] investigated determinants of housing satisfaction in post-World War II European city regions.

Wiest [

3] delved into the intricate socio-spatial dynamics of large-scale housing estates in Central and Eastern Europe.

Rowlands et al. [

4] analysed post-war European housing estate initiatives, concentrating on challenges, policies, and regeneration experiences.

Wassenberg’s [

5] dissertation chronicled the evolution of large housing estates and zoomed in on a specific case.

Dean and Hastings [

6] explored the stigma, reputation, and regeneration of three UK estates.

Hall [

7] contrasted inward- and outward-looking approaches and focused on the future of peripheral estate renewal policies in line with the outward-looking approach.

Power [

8] documented the trajectory of housing estates in five Northern European nations.

Turkington et al. [

9] curated insights on high-rise housing experiences across 15 European countries.

Muliuolytė [

10] assessed preventive measures against the decline of large estates in post-socialist cities, referencing Western European renewal strategies.

Despite various local and international studies on housing estates, the subject’s vastness and the diverse contexts across countries complicate systematic comparative research.

A pivotal study in this realm is the RESTATE project. It assessed the current state of 29 large housing estates in 10 European countries constructed post-Second World War and the policies countering their challenges. This project spurred multiple publications and fostered knowledge sharing among researchers. Building on these insights, Van Kempen et al. [

11] edited a book spotlighting the status, evolution, and issues of these post-war European housing estates.

The MCMH-EU project centred on middle-class mass housing built in Europe since the 1950s, an area often overlooked in urban and architectural studies. Seeking to fill the gap in the research, it offered a broader understanding, enriching existing studies that lack comparative and global insights. The project not only heightened awareness on the topic but also presented novel contributions to enhance current scientific methodologies [

12].

DOCOMOMO International, dedicated to documenting and conserving individual and urban-scale Modern Movement examples (including buildings, sites, and neighbourhoods), plays a significant role in this field. Its national and regional groups focus on the local needs of member countries [

13]. A notable contribution in this domain is the 2023 special issue of the Docomomo Journal. Linked to the MCMH-EU project, it delved into the exploration and comparison of middle-class mass housing in Europe from the latter half of the 20th century [

14]. Earlier, a 2008 special issue of the same journal tackled the complexities of post-war mass housing and the extensive intervention policies, emphasising documentation and conservation [

15]. Furthermore, the DOCOMOMO International Mass Housing Archive, a collaboration between the University of Edinburgh’s Scottish Centre for Conservation Studies and DOCOMOMO’s International Specialist Committee on Urbanism and Landscape, offered a digital collection of global housing estate project images [

16].

Despite varying political, social, cultural, and economic contexts, the potential of this typology, a major component of modern housing in Europe and beyond, remains ripe for exploration. Integrating housing estates into contemporary discourse enriches the dialogue on architectural strategies, urban designs, planning approaches, ideologies, and heritage significance.

Several comparative key studies, focusing on various scales and case studies, are outlined here. Caramellino and Zanfi [

17] offered an international perspective on post-war middle-class housing, presenting a comparative exploration of its construction, use, and transformation across 12 countries. Monclús and Díez Medina [

18] detailed the history of modernist housing estates, contrasting estates in the Eastern and Western Blocs, highlighting their similarities and differences. Urban [

19] delved into the history of modernist housing estates across seven cities. Scanlon et al. [

20] scrutinised social housing trends across nine European nations. Kovács and Herfert [

21] investigated the development of large housing estates in post-socialist cities through case studies. Drawing from the existing literature, Szafrańska [

22] examined the transformations in large housing estates in Central and Eastern Europe post-communism, emphasising social and spatial aspects.

These studies underscore the rich knowledge and complexity embedded in the heritage of modernist housing estates. Ongoing, multi-faceted research in comparative studies continues to unveil fresh contexts and perspectives, facilitating inter-country connections and moving the discussions to an international level.

2.1. An Overview of Modern Movement’s Housing Architecture

Since the late nineteenth century, factors such as increasing industrialisation, urbanisation, technological advances, political events, and population growth have profoundly influenced architecture and related disciplines. This shift from traditional values became apparent in evolving living conditions, daily realities, and urban environments, making the “modern” evident across various domains [

23]. Modern architecture, finding the appropriate solutions to the concerns of the Industrial Revolution, introduced new perspectives and approaches in architecture and urbanism [

24]. As society modernised, advancements across various sectors laid the groundwork for architectural designs that catered to new materials and incorporated scientific and technical innovations. Modern architecture means the liberation of the future from the past, as determined by particular cultures and times and reflected in a spectrum of buildings and ideas [

25].

Architects united under the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) to collaboratively address housing issues. Active from 1928 to 1959, CIAM was pivotal in propagating the Modern Movement worldwide. Its design tenets encompass modular construction, standardisation, varied plan solutions, and the optimisation of natural and topographical elements [

26,

27].

At CIAM 2 (Frankfurt, 1929) and CIAM 3 (Brussels, 1930), delegates addressed the “Existenzminimum” concept, which pertained to housing affordable on a minimum wage. This strategy was extensively used to tackle housing deficits, substandard living conditions, and to adjust to post-war societal shifts [

18,

28]. CIAM’s influential ideas and resolutions subsequently shaped housing projects globally [

27].

Following CIAM IV (1933), which set the “functional city” principles for urban planning, the Athens Charter of 1943 further articulated the core tenets for housing estates. The charter advocated for the partitioning of urban areas into functional zones and designing residential sectors based on topography, open spaces, climate, and greenery. It underscored the importance of enhancing urban living conditions and solidified the foundational ideology for housing estates [

29].

Post-World War II, there was a push for innovative approaches to comfort in design, construction, and stable living conditions [

30]. The “Hansaviertel”, showcased at the 1957 Interbau (International Construction Fair) in West Berlin, was a counter-response to East Berlin’s social realism. It epitomised modern living in high-rises set within a green and orderly urban framework, echoing the Athens Charter’s principles [

31].

Rapid, standardised housing construction and urban planning strategies emerged in Europe to swiftly address housing shortages, adhering to the Athens Charter principles [

18]. Housing production reached its zenith in the late 1960s and early 1970s, leading to larger-scale and taller housing estates. While large European housing estates initially followed similar design principles—like expansive block layouts and separated functions—clear distinctions emerged along certain design components [

2]. Notably, Eastern European housing estates were typically more expansive, uniform, and of lesser build quality due to economic constraints compared to their Western counterparts. The socialist ideas further contributed to the homogeneous urban aesthetic of Eastern European cities [

18].

In Western and Eastern European cities, several modern city planning examples based on CIAM principles stand out: Bijlmermeer in Amsterdam (1966–1972), Gropiusstadt in Berlin (1962–1975), Nowa Huta in Krakow (1958–1962), and Invalidovna in Prague (1950–1965). These projects, while diverse in typology, all embody radical modern principles. Notables are their functional urban architectural design achievements and the standardisation of solutions, serving as exemplary models, despite any differences among them [

18].

While modern architecture improved living standards and produced notable examples, it sometimes compromised the quality of architectural and urban designs. As the CIAM principles became increasingly radical and standardised, urban planning often lost its touch [

18]. In 1972, the Pruitt Igoe residential complex in St. Louis, designed by Minoru Yamasaki in 1955, was demolished due to issues such as severe poverty, crime, racism, and social decay. This event marked both the decline of large-panel construction in Western nations and symbolised the end of the modernist era. Pruitt Igoe stands as a poignant example of the limitations and miscalculations of modernist urban ideals when contrasted with real-world conditions. Yet its demolition also heralded the emergence of new architectural thought [

32,

33]. It is crucial to note that while some modernist housing projects faced challenges, many remain as treasured architectural assets. In our era of commercialised spaces, there is a renewed appreciation for the Modern Movement and its enduring architectural legacy that merits preservation.

2.2. Twentieth Century Modern Movement Housing Estate Architecture: Impacts in Turkey and Poland

To effectively compare two distinct regions, it is crucial to understand their historical developments. This context aids in grasping the evolution of modern architecture locally and the significance of housing both nationally and internationally. In addition, being aware of the existing background enables us to understand the risks and threats and promotes the sustainable and adaptive use of architectural heritage.

Turkey: In 1923, the founding of the Republic of Turkey catalysed significant urban shifts. This era, marked by foreign interventions, migrations, and economic flux, ushered in diverse societal transformations. Eager to establish an autonomous nation, Turkey embarked on holistic modernisation efforts spanning economic, social, institutional, and urban sectors [

34]. As cities rebounded from wartime devastation, the 1930s saw Turkey’s embrace of modern architecture. Western-inspired mass housing projects, cooperatives, and rental homes became pillars of the state’s modernisation vision [

35]. Established in 1926, Emlak & Eytam Bank bolstered construction efforts, while the 1930s heralded a surge in cooperative housing. By 1935, Bahçelievler in Ankara was initiated as the inaugural garden-city housing model, setting a precedent for subsequent cooperative developments [

36].

From 1923 to 1950, Turkey embraced an architectural approach that was both modern and nationalistic. This was in line with the state-centric development model, where modernisation was pursued by mirroring Western standards yet within the framework of national identity [

37].

After World War II, Turkey experienced heightened social mobility. Migration trends reshaped lifestyles, leading to a surge in the population of civil servants and workers inclined to apartment living in industrialised cities. The 1944 Civil Servants Law catalysed the creation of numerous housing estates [

38]. In 1946, the foundation of Emlak Kredi Bank boosted credit accessibility and tax incentives, paving the way for the emergence of housing projects with reinforced concrete slab block construction. The 1950s marked a significant shift as Turkey began opening up, integrating liberal policies and forging international connections. Despite its insular approach during World War II, Turkey began engaging globally [

39,

40]. This era was characterised by universalism and rationalism, highlighted by Turkey’s entry into the United Nations (1945), the adoption of a multi-party system (1946), endorsement of the Marshall Plan (1947), and NATO membership (1952) [

41]. From 1950 to 1980, the previous dominant state-centric policies began to transition towards liberalism, and with increased private sector involvement in industrialisation, rapid urbanisation ensued [

37].

The 1965 Condominium Ownership Law marked a pivotal shift towards the proliferation of apartment buildings. With a surge in housing demand, new zoning rights were granted, leading to a rise in multi-storey apartment developments [

39,

42]. Urban density increased through the 1960s and 1970s. The 1980s ushered in innovations in construction materials and technology. Following the military intervention, comprehensive transformations occurred across socio-cultural, economic, and political spheres. Legislation in 1981 and 1984 catalysed housing estate developments, favouring mass housing production and supporting major projects. This was in response to housing shortages and expanding informal settlements. A departure from national identity resulted in overbuilt urban environments [

37,

40,

43].

Poland: After World War I, Poland reclaimed its independence following 123 years of partition. The nation not only pursued modernisation and swift development but also sought its own architectural identity [

44]. Post-World War I reconstruction took precedence until the late 1920s, with a focus on creating new residential areas and especially public buildings. Emphasis was placed on rejuvenating major cities, establishing municipal centres, and forming housing estates [

45]. However, the onset of the Second World War interrupted this progress. Post-World War II, Poland’s political landscape transformed, coming under the Soviet Union’s influence as the Polish People’s Republic and joining the bloc of communist nations aligned with the USSR. This ushered in new borders, population shifts, a revamped communist political structure, and heightened ideological pursuits [

44].

From 1945–1949, the modernist architectural ideals from the pre-war era persisted. However, between 1950 and 1956, they were supplanted by “socialist realism”. This style, diverging from modern functionalism, was described as “national in form and socialist in essence” [

46]. Housing architecture was heavily influenced by Soviet templates and rigorous political oversight. Grand urban designs featuring expansive streets catered to the working class and heavily adorned monumental structures epitomised a communist society dominated by the proletariat [

33]. After the socialist realism era, architecture made a return to modernism and avant-garde influences. Despite the political backdrop, this era is referred to as “thaw”, as it is during this that architects began to experience relative freedom.

During the late 1960s and 1970s, architecture took on a utilitarian and economical character. To address the housing crisis, industrial and swift methods were essential. Housing designs became standardised, with the state overseeing the production of mass housing that bore striking similarities. This period marked the advent of industrial development, characterised by large slab technology [

33,

45]. Large-scale housing, typically of 5 to 11 storeys, was constructed using industrialised techniques [

47,

48]. By 1970, the production of these large housing estates peaked, being viewed as instruments of social change and enhanced living standards, particularly for the working class. While Western European nations regarded this typology with scepticism, it became prevalent in socialist countries due to systemic and political imperatives. This trend persisted until the fall of communism in the 1990s [

29,

49].

3. Materials and Methods

This research serves as a pilot study, with one of its goals being the refinement of the comparative analysis method for future investigations. It juxtaposes specific instances to draw more comprehensive insights.

Ragin and Rubinson [

50] view comparative research more as a perspective or orientation rather than just a method. This research approach intertwines theoretical concepts with empirical data. Though often classified as a research methodology, it leans towards qualitative analysis and employs various methods, including case study analysis. Even though comparative research can be seen as a distinct research design, its foundational principles are ingrained in numerous research endeavours, challenging its classification as an entirely separate method [

51,

52]. Pickvance [

53] categorised comparative analysis into two primary aspects: (1) an interest in understanding the reasons behind similarities and differences across cases and (2) an emphasis on gathering data within a shared framework. The primary drive for comparative analysis stems from a desire to delve deeper into the causal mechanisms that underscore relationships or events.

The relationships among the cases are understood in light of their present contextual backgrounds. When these cases are juxtaposed against varying processes within the chosen time frame, assumptions become clearer, and specific details are contextualised within a broader scope. This research intertwines theoretical insights with data from case study analyses, facilitating a deeper comprehension of individual cases and highlighting the parallels and differences between them.

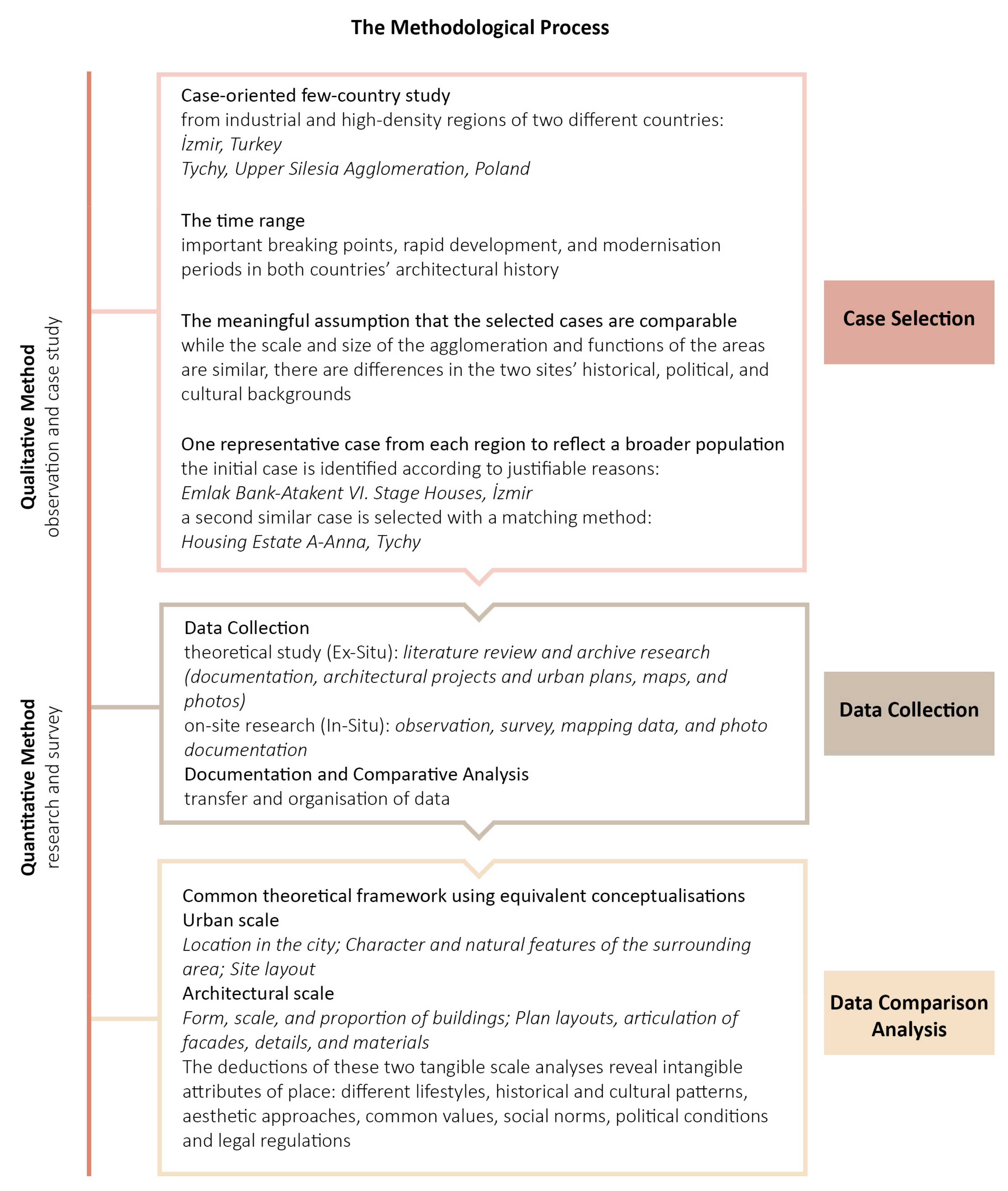

The procedure comprises sequential stages of case selection, data gathering, and comparative data analysis. A summary of this methodological process can be found at the end of this section in

Figure 1.

3.1. Case Selection

Selecting the appropriate case for comparison is fundamental in conducting a comparative analysis. This ensures that the analysis is structured systematically. Landman [

54] categorises comparative studies into three types: multi-country, few-country, and single-country. Single-country and few-country studies are typically case-centric, making it essential to select cases that are genuinely comparable [

55,

56].

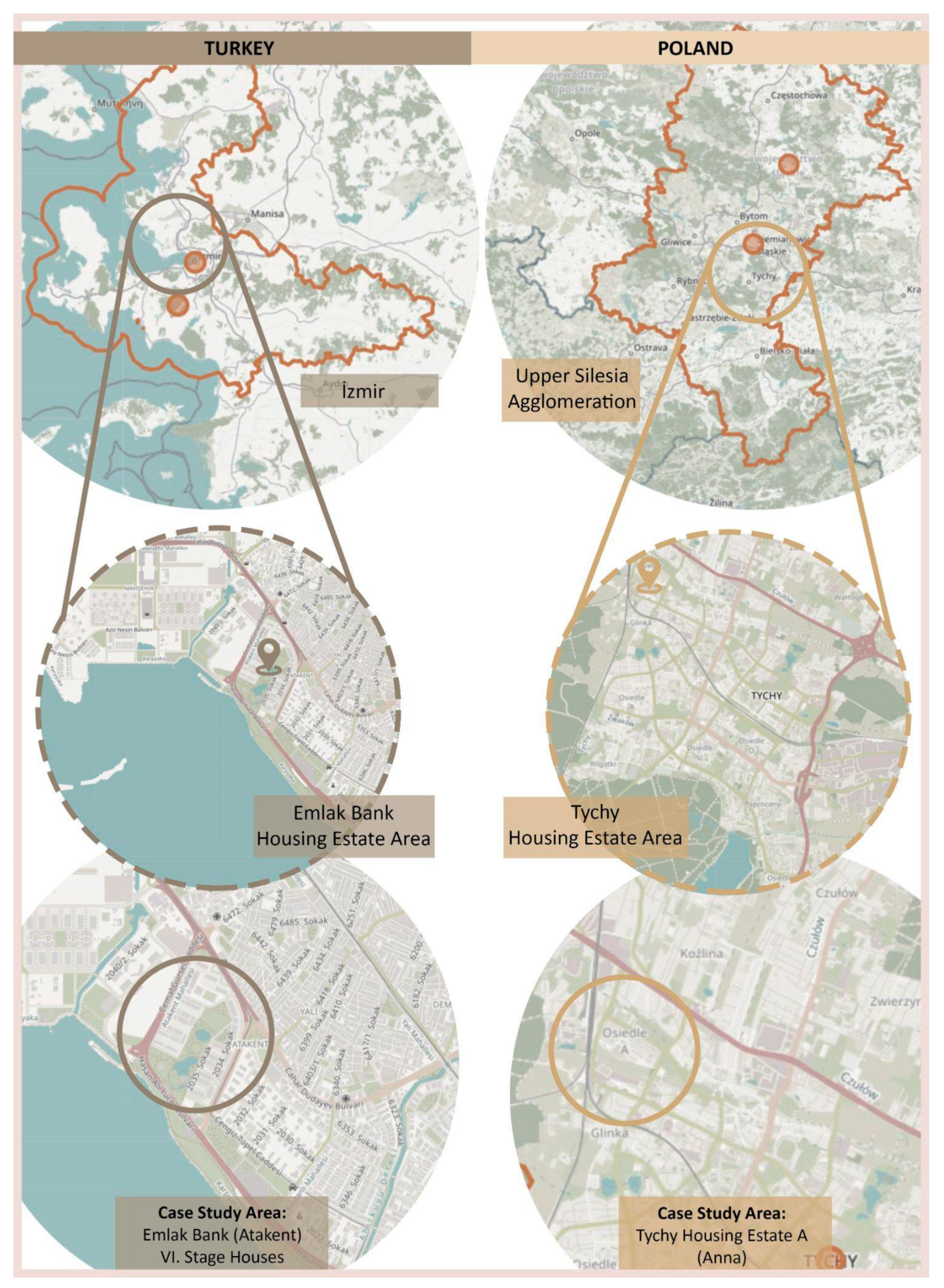

This study examines multi-storey houses, housing estates, and their urban designs in Izmir, Turkey, and Tychy, Upper Silesia Agglomeration, Poland, constructed between 1945 and 1990. The selected regions are industrialised, high-density areas from two distinct countries. The timeframe for this investigation captures significant milestones, rapid growth, and modernisation phases in both Turkish and Polish architectural narratives.

Azarian [

57] posits that every comparative analysis presupposes that the chosen cases are analogous. While the agglomeration’s scale, size, and functions are akin for both sites, they differ in their historical, political, and cultural contexts. This study hypothesises that despite modernism being seen as an International Style, these variations have influenced the unique nature of modernist architecture in local settings, particularly evident in urban residential zones. Through comparative analysis, this study seeks to highlight this distinct architectural character as a significant value.

The rationale for selecting Izmir and Tychy for this comparative analysis includes:

Similarities in the scale and size of the agglomeration and functions of both areas.

Both locales have been directly influenced by their unique socio-historical, economic, political, and cultural contexts.

Both represent high-density, industrialised regions within distinct countries.

There is a notable gap in comprehensive studies focusing on housing—particularly multi-storey homes, housing estates, and their urban layouts—in both places.

The existing literature is scant on direct comparisons between these two areas.

Both sites showcase a rich diversity of quality housing that warrants documentation and analysis.

The selected housing typologies in both regions are facing rapid changes due to several factors: evolving societal needs, renovation endeavours, city policies, a lack of recorded data, and limited conservation awareness.

As highlighted by Gerring [

58], a case study deeply examines a single unit to gain insights into a broader set of similar units. In this study, we have selected a specific site from both regions to conduct an in-depth comparative analysis. Esser and Vliegenthart [

59] emphasise the importance of precisely delineating case boundaries. These constraints can be influenced by factors like geography, time, culture, structure, or function. Picking a case that exemplifies a broader group is challenging [

60]. The process of selecting a case comes with limitations, such as resource constraints and the availability of data. Hence, the researcher’s role becomes pivotal in determining the data selection process, as well as setting the criteria for the inclusion or exclusion of potential cases [

61].

Gerring [

62] categorises case selection techniques into nine distinct methods: typical, diverse, extreme, deviant, influential, crucial, pathway, most similar, and most different. The “most similar” method, frequently employed in case selection, picks cases that seem similar on the surface but result in different outcomes [

62]. Typically, an initial case is identified, and a subsequent case resembling the first is selected based on certain criteria [

63].

In complement to Gerring’s theory, Pavone [

64] introduced a methodology wherein the most similar case is identified inductively after a single case has been chosen. In this approach, the researcher believes there are sound reasons behind the initial case selection and works towards contextualising the results they obtain. This inductive strategy strives to capture a more expansive empirical and theoretical understanding in the case study, addressing the question of why a particular case should be examined prior to drawing broader causal generalisations.

Nielsen [

63] proposes various “matching” techniques for selecting cases in the most similar case analysis. These methods aid analysts in drawing justifiable conclusions within their case study. By employing matching techniques, researchers can identify cases with sufficient similarities, thereby strengthening the case for their comparability. The primary advantage of these matching methods is their ability to assist analysts in identifying a subset of units with notable similarities.

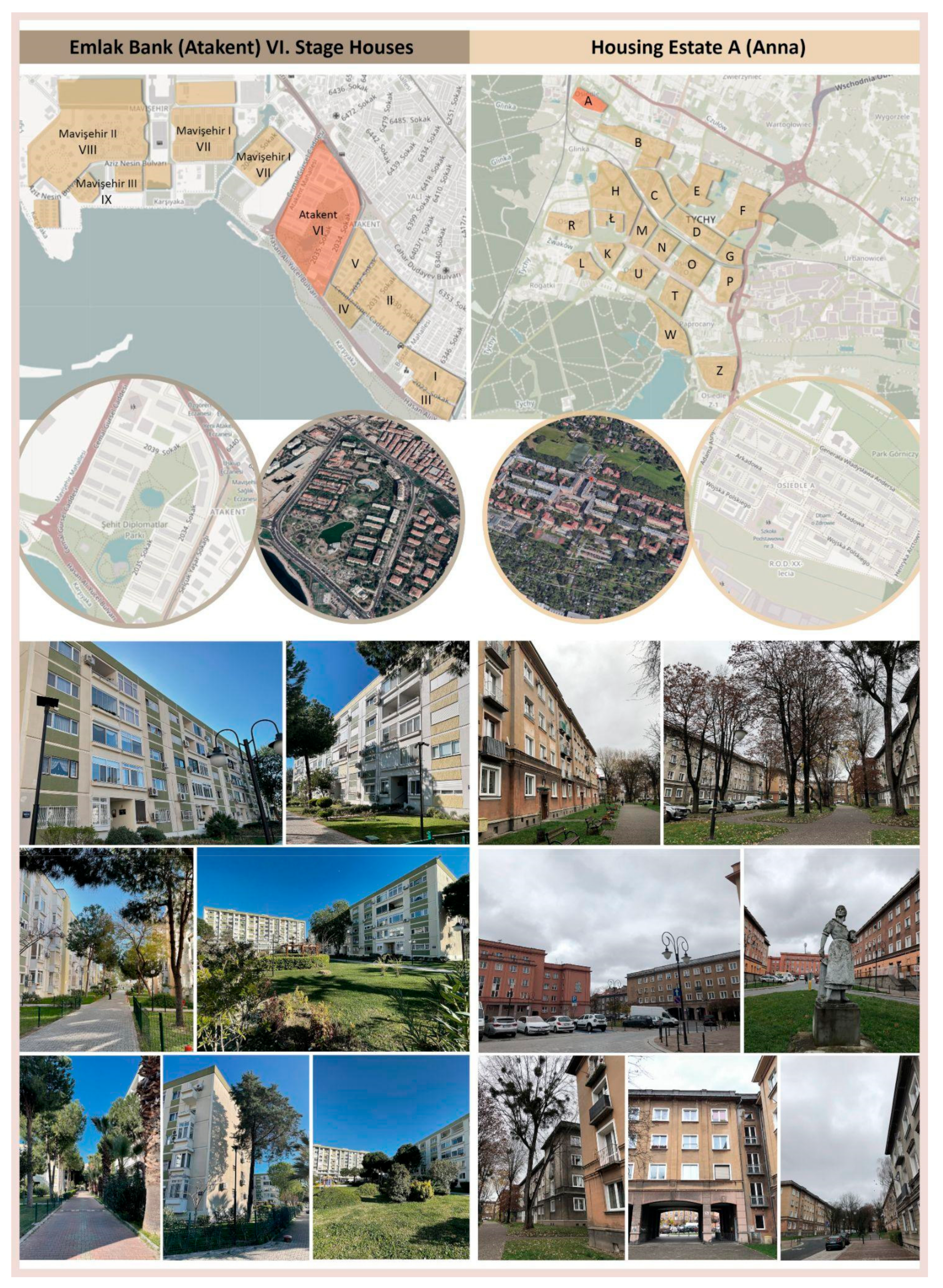

After determining the first case from Izmir (i.e., Emlak Bank-Atakent VI. Stage Houses), the process to identify a comparable case from Tychy was initiated. This first representative case was chosen with reference to post-1980, a major breaking point with new developments, material technologies, production, and accessibility. This corresponds to a period in which various housing estate laws and social, economic, and political transformations changed the urban space.

The matching method was employed to find a corresponding site in Tychy that exhibited similar characteristics in terms of scale, urban layout, and overall design form yet differed in the local influences exerted by the region’s unique historical, political, socio-economic, and cultural contexts. The goal was to identify a case in Tychy that, while adhering to the principles of modernist architecture (reflecting the International Style), also showcased how local specificities influenced the architectural and urban design outcomes. The aim was not merely to find structural or visual similarities but to discern how local contingencies in Tychy (like the influence of Soviet architecture, political mandates, or socio-economic changes) might have diverged from those in Izmir, despite operating under a broader modernist umbrella.

Through this methodological approach, the comparative study would unearth how two different regions responded to overarching modernist principles while navigating their local conditions. The juxtaposition of these two cases would allow for a deeper understanding of the intersections between global architectural trends and local specificities.

The choice of “A” Anna Estate in Tychy as a counterpart to the Emlak Bank-Atakent VI. Stage Houses in Izmir is pivotal for this study. It accentuates the essence of the comparative method; that is, to juxtapose two cases with apparent similarities in design, form, scale, and urban layout, but which were born out of contrasting historical, political, and economic contexts.

Based on the research assumptions, the reason for the selection of the two locations can be categorised into the following urban planning and architectural aspects, as well as selected social characteristics:

Urban planning and architectural aspects:

Reflecting the prevailing architectural trends of the period.

Originality in terms of architectural details, materials, and construction technologies.

Incorporating different facilities and natural features.

Maintaining the original form and design principles from the period in which they were constructed.

Comprising various residential patterns with distinct building shapes, floor heights, facade characteristics, details, innovations, and technological developments.

Exhibiting different proportions and scales in terms of urban layout and placement within the city.

Featuring varying population densities in relation to communication systems.

Social aspects:

Reflecting the living conditions, social dynamics, cultural influences, economic factors, and political contexts of the period in which the sites were built.

Actively used by city residents and fostering a strong connection between residents and their living environment, contributing to a sense of identity.

Leaving a lasting imprint in the architectural and public memory of the city.

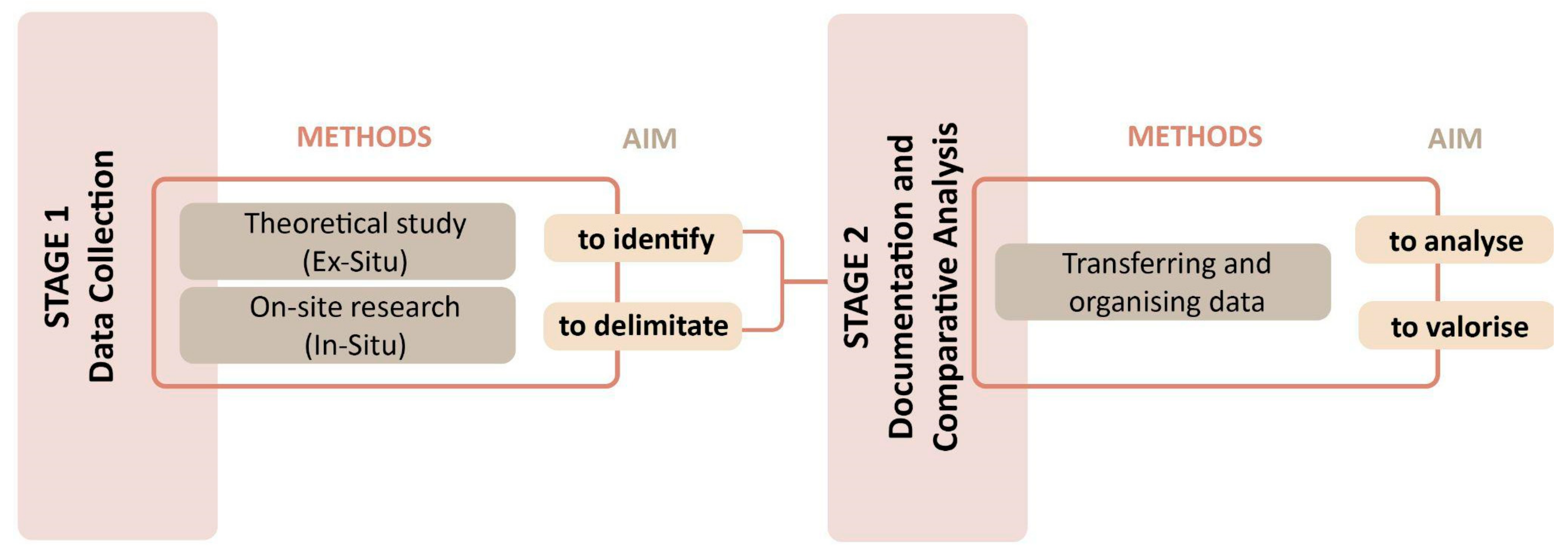

3.2. Data Collection

This study is structured in two primary phases: (1) data collection and (2) documentation combined with a comparative analysis of the data, as illustrated in

Figure 2. This approach facilitates the systematic gathering, organisation, and interpretation of information, serving as an effective means to record, convey, and manage data.

In the first stage, both ex situ and in situ research methods are employed. The ex situ component encompasses a literature review and archival research, which dives into documentation, architectural blueprints, urban planning designs, maps, and photographs. The in situ component involves direct on-site investigations, including observations, surveys, data mapping, and photographic documentation. The latter visually captures the layout, environment, and exterior designs of the chosen residences. All gathered written and visual data are then digitised, paving the way for in-depth architectural and urban evaluations. The objective of this stage is to amass information that pinpoints and demarcates specific areas for case study scrutiny.

The second stage revolves around the systematic transfer and organisation of these data, laying the groundwork for in-depth analysis and valorisation. Hence, the instruments and methodologies chosen for each stage are tailored to support data collection, their subsequent analysis, and final value assessment.

3.3. Data Comparison Analysis

To derive meaningful insights from a comparative analysis, it is imperative that cases are evaluated within a unified theoretical framework, ensuring uniform conceptualisations and methodologies [

59]. Cities possess distinct identity markers shaped by the interplay of natural, social, and built elements [

65]. This study proposes a comprehensive theoretical framework that encompasses urban and architectural scales, integrating facets of natural identity, individual and societal identities, and artefact-driven identity. By examining housing estates in Izmir and Tychy—each embodying international architectural trends and nuanced local modernism—the analysis sheds light on their commonalities and distinctions, rooted in their respective modernist contexts. This data-driven scrutiny relies heavily on objective findings from literature reviews and archival research, further enriched by on-ground observations and documentation.

The urban and architectural analyses are broken down as follows:

Urban scale analyses:

City placement: understanding where the estate is situated within the urban landscape.

Surrounding character and natural features: examining landscape attributes and the relationship the estates share with green or open spaces.

Site layout: analysing the composition of the estate, including elements such as principal axes, urban interiors, dominant structures, scale, density, typology of buildings, and transportation infrastructure like roads and pedestrian pathways.

Architectural scale analyses:

Building form, scale, and proportion: these elements indicate the prevailing architectural approach of the specific era and locale.

Plan layouts and facade articulation: Investigating the building’s internal configuration and how its exterior presents itself in terms of design elements, features, and materials. This can shed light on innovations and technological advancements of the time.

These aspects provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating and comparing the selected case studies in both urban planning/architectural and social dimensions. Comparative analysis delves beyond the tangible facets of housing estates and their urban configurations, offering insights into intangible dynamics. These include the diverse lifestyles they accommodate, the historical and cultural narratives they echo, aesthetic paradigms they adhere to, shared values they promote, societal norms they reflect, and crucially, the overarching political landscapes and legal frameworks they operate within. Additionally, the analysis probes into both spatial and societal elements of the two sites, spotlighting communal spaces that nurture local community growth and engender the intangible attributes of a place. By organising the comparison into these categories, the research can elucidate the interplay between design decisions and their socio-cultural implications. These tangible and intangible facets to be obtained have the potential to be widely accepted as fertile ground for sustainable development.

4. Case Study and Collected Data

Izmir, ranking as Turkey’s third-most populous city, stands as a linchpin in historical, economic, and socio-cultural contexts. Strategically positioned, it has historically flourished as a pivotal settlement. The transformations and socio-cultural and economic shifts witnessed in Izmir’s history have largely mirrored the broader trends and developments in Turkey.

The comprehensive timeline of Izmir’s urban and architectural evolution can be segmented into the following phases:

1923–1930: Following the devastating fire of 1922, there was a strong desire to transform Izmir into a modern city. Initial planning focused on rebuilding the fire-ravaged areas. During this period, the First National Architectural Movement emerged. Urban and architectural developments in Izmir during the Early Republican Era mirrored the parallel trends in the country.

1930–1950: This era was marked by a juxtaposition of realism and idealism in housing, reflecting Izmir’s aspiration to embody a modern and new national identity. The 1940s saw the introduction of the city’s first apartment buildings and reinforced concrete structures. Coinciding with burgeoning nationalist narratives, the Second National Architectural Movement emerged during this time [

66].

1950–1965: Political shifts significantly influenced housing production during this period. The burgeoning urban population led to a surge in housing demand, mirroring a universalist and rationalist modern architectural language. The imprints of the Early Republican Period, which saw the city’s reconstruction, started to wane. The national discourse and populist strategies gave way to the adoption of the International Style [

37].

1965–1980: The introduction of the Condominium Law in 1965 spurred the construction of high-rise apartment buildings, particularly along the city’s coastal regions [

66]. This era saw rapid urbanisation, the emergence of populist zoning policies, and rising rent concerns. It was marked by significant alterations to the city’s fabric, with extensive demolition and reconstruction in line with legal stipulations [

37].

Post-1980: The city experienced a significant population surge due to migration, leading to expansive urban sprawl. Economic and socio-cultural disparities became more pronounced [

37,

39]. To address the rising housing demands and burgeoning informal settlements, there was a shift towards large-scale housing production, with housing estate strategies being implemented [

66].

Tychy, situated within the Upper Silesia Agglomeration in southern Poland, has experienced its urban and architectural evolution under the influences of shifting borders, political upheavals, and economic fluctuations. These factors have significantly shaped the architectural and urban planning landscape of the entire Upper Silesia region.

The urban and architectural progression of Upper Silesia can be segmented into the subsequent periods:

1921–1945: During this time, the Upper Silesia region was partitioned between two nations: a portion was under German control, while the other was part of the Polish Republic. In the German-controlled sector from 1921–1933, the modernist architectural style flourished under the Weimar Republic’s influence. However, from 1933–1945, under the Third Reich, a more nationalistic architectural style was predominant. Meanwhile, in the Polish section from 1921–1939, the architecture reflected the modern style of the newly reestablished Polish state.

1945–1949: Post-WWII brought significant geopolitical shifts, resulting in the entire Upper Silesia region falling under the jurisdiction of the Polish People’s Republic, which operated under a communist system.

1950–1956: The era of “Socialist-Realism” dominated architectural and urban planning. This approach, which promoted a fusion of “national in form and socialist in essence,” marked a departure from avant-garde trends. The designs featured classic architectural elements, mirroring the ideology of Soviet socialism, and embraced monumental urban layouts.

1957–1970: During this period of political “thaw,” modern architectural trends re-emerged prominently. This era witnessed the creation of several outstanding examples of avant-garde architecture.

1970–1980: This decade was marked by swift economic growth and the country’s increased openness to the West, leading to a remarkable surge in industrial, sports, service, and residential construction projects.

1980–1989: The decade was characterised by an economic downturn and a lull in construction activities, compounded by the beginnings of an economic transition and the disintegration of state-run design offices.

Post-1989: With the onset of economic reforms, there was a resurgence in private investments and a noticeable shift towards post-modern architectural influences.

The selected case of Tychy in Upper Silesia serves as an ideal reflection of the spatial developmental changes observed during the specified periods.

Tychy, a city conceived in 1950 due to state political decisions, was meticulously designed from scratch. Each district, constructed consecutively, offers a clear representation of the evolving phases of Polish architecture and urban planning. Consequently:

1951–1956—Estate “A”: A compact cluster of structures featuring a classically inspired urban layout, traditional construction techniques, and a harmonious building scale.

1956–1959—Estates “B” and “C”: Designed on the scale of a smaller city, these estates showcase picturesque street and square layouts.

1959–1970—Estates “E”, parts of “D”, and “F”: Representing the city’s most avant-garde developmental phase, these areas have varied multi-family housing styles ranging from terraced and atrium designs to larger complexes.

Post-1970—Marked by the swift construction of high-rise edifices using large-panel technologies, known colloquially as “house factories”.

1982–1983—The era began to show the first indications of a looming crisis and subsequent stagnation [

67].

Emlak Bank Atakent Houses, situated in Karşıyaka, Izmir (refer to

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), represent the sixth phase of the Emlak Bank housing estate initiative. As Izmir experienced swift urbanisation due to increased migration, Emlak Kredi Bank set out to regulate this rapid construction while addressing the housing deficit. Starting in 1969, the bank established a cooperative housing zone in Karşıyaka-Bostanlı, developed in nine successive stages. With the progression of industrialisation and technological advancements in the 1980s, Emlak Kredi Bank revised its housing construction approach. The bank opted to create satellite city-style settlements, encompassing landscaping, social, cultural, and commercial amenities. The VI. phase showcases the adaptations in the bank’s housing construction policy, designed to cater to the evolving societal needs [

69,

70].

Housing Estate A (Anna), situated in Śródmieście, Tychy (refer to

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), represents the inaugural project of the newly envisioned city. Constructed between 1951 and 1956, this period saw modernist architectural expressions being overshadowed by the politically mandated style of socialist realism. The project was the brainchild of Professor Tadeusz Teodorowicz-Todorowski and his collaborative team [

71]. Despite being schooled in modernist architectural principles, Teodorowicz-Todorowski had to navigate and comply with political mandates. Notwithstanding these constraints, he adeptly merged the demands of the dominant style, producing a housing estate that was well scaled and simple in architecture, devoid of the monumental traits commonly associated with socialist realism structures. As a continuation of this initiative, subsequent housing estates were developed, each named after the initial letter of a female name, such as B, C, D, and so forth [

72].

Post-1956, after the era of socialist realism had ended, more housing estates sprouted in Tychy. This city’s growth was embedded in the deglomeration strategy for Upper Silesia, inspired by global urbanisation trends and the significant population surge in post-WWII Europe. The Upper Silesia deglomeration blueprint was bifurcated into two zones: A, earmarked as the industrial nucleus, and B, enveloping Zone A, earmarked for residential estates. Drawing from the garden-city paradigm and grounded in a socialist economic framework, the strategy aimed at urban revitalisation and reconfiguring existing industrial zones. The decision to refurbish and expand the city was crystallised in 1950, with a city design competition that drew in prominent architects to submit their visions, culminating in the selection of the final city plan [

71].

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of selected local contexts (elaborated by the authors).

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of selected local contexts (elaborated by the authors).

| | Emlak Bank (Atakent) VI. Stage Houses | Housing Estate A (Anna) |

|---|

| Urban Scale |

| Location in the city | | |

| Character and natural features of the surrounding area | | |

Functional classification

- ○

Residential buildings density in the surroundings because of the proximity of both sites to other housing estate areas. - ○

Commercial, education, retail, local, and health facilities.

Accessibility

- ○

Readily accessible via public transportation.

- ■

In Atakent VI. Stage Houses, the district has various bus and tram stops. - ■

In Housing Estate A, the district has various bus stops and a train station stop.

The transportation system is easily accessible by car or on foot.

- ○

Wide vehicle roads. - ○

Pedestrian roads. - ○

Parking lots.

Ecological aspects of the area

- ○

Large green areas, parks, and open spaces.

|

| Site layout | The design centres around a large green space, with three distinct housing zones situated around it. Buildings are arranged in a distinct layout.

| The site follows a geometric and axial design, anchored by a central square. While some buildings stand independently, they are thoughtfully designed to complement and relate to one another.

|

|

| Architectural Scale |

| Form, scale, proportion of buildings and building complexes | The design prominently features multi-storey apartments with cubic, symmetrical facades, a style prevalent along Izmir’s coast after 1950. These structures embody modern architectural principles like prismatic compositions, symmetrical facade designs, flat roofs, unbroken sill lines, and horizontal windows. While Stage VI includes buildings of varying heights, the studied area predominantly consists of five-storey structures.

| Housing Estate Anna exemplifies socialist realistic architecture, illustrating a departure from modernism and a return to classical design models. With three or four floors, the buildings are not particularly tall compared to other housing estates in Tychy.

|

|

| Plan layouts, articulation of facades, details, materials | For the Stage VI houses, the building facades exhibit a straightforward architectural approach: vertical lines, prismatic forms, and clean geometric shapes.

- ○

Linearity and consistency are achieved through floor slabs and balconies designed as a continuous surface on the front facade.

Because of the standardisation stemming from construction technology, various room counts and floor plans were devised to cater to diverse needs across the housing estate. Local materials and methods were melded with a minimalist modernist aesthetic on an architectural scale. The tunnel formwork, an industrialised construction method, was employed.

| In Housing Estate Anna, the building facades showcase a plethora of architectural elements, including cornices, pilaster strips, rustication, attics, columns, balustrade balusters, coffering beneath the roof eaves, and arcades.

- ○

The facades, entrances, and surroundings are adorned with sculptures, reliefs, and sgraffito that represent the residents’ professions, such as miners, metallurgists, and masons, along with motifs of folk traditions—a characteristic feature of the Soc-Realism period. At stair entrances, plaques are installed, serving not only as decorative elements but also as navigational aids within the site. These plaques predominantly depict zoomorphic designs, but they also feature botanical elements like mushrooms or flower bouquets [ 72].

The initial apartments in this area feature spacious floor plans, which pre-date the standard introduced in the 1960s that reduced apartment sizes [ 72]. The entire estate was constructed using traditional brickwork technology.

|

| | The facades exhibit a harmonious interplay of horizontal and vertical elements, punctuated by rhythmic window openings. The designs are characterised by a blend of rationalist, functionalist, and national styles, both in plan layout and facade aesthetics.

|

| Spatial–Social Selected Aspects |

| Intangible aspects of the interconnected public and communal areas | Both sites incorporate semi-private and public recreation areas.

- ○

The inward-facing positioning of buildings creates inner courtyards, forming semi-private spaces. - ○

Main squares, open areas, and pedestrian pathways within the sites serve as public spaces, fostering a social atmosphere and serving as gathering spots for residents.

Both sites feature landscaping to enhance the quality of living.

- ○

Buildings are arranged around the central square. - ○

Parks and green spaces within the sites encourage public interaction.

Both housing estates are cherished by their residents for their spatial and cultural values, contributing to socially vibrant spaces and the growth of local communities. These conclusions are drawn from on-site observations of residents’ behaviour and their dedication to their homes and shared areas.

|

5. Results and Discussion

This section seeks to enrich the existing theories and prior literature by juxtaposing two local case studies. In assessing the housing estates from the modernism era at a local level, we have incorporated a theoretical historical backdrop to contextualise the broader narrative. This integration is crucial for aligning local practices with the international discourse on modernist architectural heritage. By tapping into universal values for local discussions on modern housing estates, this analysis furthers our understanding of urban strategies. Additionally, the synthesis of both local and international historical contexts enables us to identify parallels and disparities when comparing these two local examples.

Above, in

Table 1, we juxtapose the characteristics of the two selected settlements at both urban and architectural scales. The urban scale examines elements like the site’s placement within the city, surrounding characteristics, the development’s urban layout, and the configuration of public spaces. The architectural scale contrasts features such as building form and size, plan layout, facades, materials, and details. The table’s final row highlights the spatial and social facets of the two settlements, emphasising pro-social areas that nurture local community development and the fostering of intangible place values.

The table uses separate cells to highlight differences between the two study areas. Shared cells emphasise their similarities, referencing the Modern Movement’s principles.

6. Conclusions

Multi-storey buildings, housing estates, and the urban layouts they embody have evolved as products of accumulated societal experiences. Economic, social, cultural, and political forces within society have played a pivotal role in shaping and diversifying architectural perspectives. These multi-storey structures, housing estates, and their associated urban designs have endured through time and hold significance in the realm of urban identity and architectural culture to this day. This study introduced a unique comparative analysis approach for Izmir and Tychy, aiming to enhance our understanding of architectural heritage from the latter half of the twentieth century, with a specific focus on housing estates and their urban designs. Two main research questions were posed to shed light on the characteristics of Modern Movement housing estates in the twentieth century and how various local factors, including spatial, social, economic, and political elements, influenced them. Through this comparative analysis, this study facilitated the exploration of heritage effects in two distinct representative areas within both universal and local contexts. This approach was effective in uncovering, defining, and promoting the sustainability of values by enabling the exchange of international knowledge within local contexts. Although the findings can be generalised to similar settings, they also highlight that the process operates differently based on local variables.

The second research question focused on the methodology for comparing housing architecture and the specific aspects from which this comparison can be made, aiming to identify similarities and differences within local contexts. The theoretical framework, which encompassed elements at both urban and architectural scales and integrated universal and local principles, elucidated the variables that influence the reception of modernist housing in two distinct local contexts. This framework enabled the generation of new insights while adhering to the initial research assumptions.

By concentrating on the comparative analysis of architectural heritage from the second half of the 20th century within local contexts, this study introduces a more systematic approach to architectural history research. It underscores the significance of residential Modernism’s heritage in terms of values and conservation. The insights derived from this comparative analysis, comprising physical and archival evidence, can be instrumental in conservation initiatives. Additionally, on a broader scale, the gleaned knowledge from local contexts has the potential to serve as a reference in urban and architectural planning endeavours.

Undertaking such research aims to address the gaps in the literature pertaining to modern housing. It seeks to unveil, delineate, and safeguard the heritage values associated with modernist housing estates. The proposed analysis serves as a means to identify the unique attributes that form the identity of specific locales, offering a foundation for their preservation. By shedding light on the values derived from the comparative analysis, it fosters awareness regarding the conservation of these buildings’ heritage.

The analysis outlined in this study provides a foundation for future research development. It serves as an initial step towards a comparative analysis aimed at assessing twentieth-century housing architecture within the context of cultural heritage. Through comparative findings, this research has the potential to delineate local values and enhance discourse within the global framework. Subsequent studies can build upon these insights to further enrich our understanding of modernist housing heritage.