1. Introduction

The people of China now live longer. The increased life expectancy is driven by healthy living, the elimination of infectious pathogens, and the treatment of non-communicable diseases [

1,

2]. These developments have been possible due to a colossal investment by the Chinese government into food security, medical advancement, and making available more affordable and accessible healthcare [

3,

4]. However, some of the policies of the government directed at improving the lives of Chinese people have induced structural population shifts [

5], with epidemiological and socio-economic implications [

1]. For instance, the spillover effects of the one-child policy are the looming low-fertility trap and rising dependency ratio (which reflects the number of elderly people per one hundred working-age adults) [

6]. Another is that the rapid economic development in urban centers has sped up rural–urban migration, creating left-behind children and elderly people with little support systems [

1,

6,

7]. At present, there are 267.36 million Chinese people aged 60 years and above, accounting for 18.9% of the population compared to 13.9% of the total population in 2010—just a little over a decade ago [

8]. More troubling is the fact that about 200.56 million of the aging population are at least 65 years old—the largest globally. The health of the elderly (aged 60 and above) in China is, therefore, a matter of national security with global implications that needs to be addressed.

Meeting the healthcare needs of the elderly is dependent on an intricate mix of fine insights into the physical and psychological health of the elderly, their socio-economic capital, and other critical support systems, including healthcare infrastructure. As China officially joins the “aging nations”, it is crucial to recognize her unique characteristics, such as getting old before getting rich, large regional wealth differences, family dependency, and, importantly, “being not ready to get old” [

6,

9]. How well the elderly live in China is a key question of scientific inquiry. Most often, the elderly’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL)—defined as “a multidimensional concept with both objective and subjective factors that refer to general satisfaction with life or its components” [

10]—has been used as an indicator of a good/bad life [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Findings from extant studies depict an inconsistent picture of the elderly’s HRQoL. Some studies show a rising HRQoL of the elderly (e.g., [

15]) whilst others indicate a falling trend (e.g., [

16]). Additionally, the HRQoL of the elderly in underdeveloped areas [

17,

18], and those in institutional care [

19,

20], is found to be poor. With rapid economic development lifting millions from rural poverty through “digital dividend” [

21] and consistent government investment in institutional care [

3,

4,

22], the nature of the evolution of the HRQoL of the elderly across care models and regions of domicile over the years is uncertain. Additionally, the rising dependency ratio implies that little time and attention may be dedicated to caring for the elderly [

23], particularly those in the home-based care model. There is therefore an urgent need to establish the patterns of change in the elderly’s HRQoL through time to put investment in intervention policies and programs [

3] geared toward improving the HRQoL of the elderly into perspective. Our research responds to this need. We therefore attempt to answer the following questions: (1) Is the HRQoL of the elderly in China rising or falling over the years (i.e., from 2000 to 2020)?; (2) To what extent does this change (rise or fall) differ across the different elderly care models adopted and the regions of domicile?; (3) Lastly, how does the rising dependency ratio impact the HRQoL of the elderly over the years?

To answer the aforementioned questions, we adopt a cross-temporal meta-analytic (CTMA) approach to examine the changing trends in the HRQoL of the elderly in China from 2000 to 2020, with age (publication year) as the independent variable. This approach is considered appropriate as traditional meta-analytic methods fail to account for the “age effect” of perceptual variables [

24]. That is, the CTMA technique eliminates measurement errors introduced by age effect (publication year) and can, thus, disentangle the nature of association between psychological variables and socio-economic indicators to explain how social and economic changes affect individual psychological development [

25]. The dynamic nature of the current socio-cultural and techno-economic developments necessitates continual evaluation of how these developments influence important life goals and psychological wellness [

26,

27,

28]. Therefore, CTMA has been utilized to reveal changes in social support systems for the elderly [

29] and the mental health of middle school students in China [

24,

28]. In addition to the within-scale variability assessment, we employ conventional meta-analytic techniques to examine the differences in HRQoL across groups of elderly people.

4. Discussion

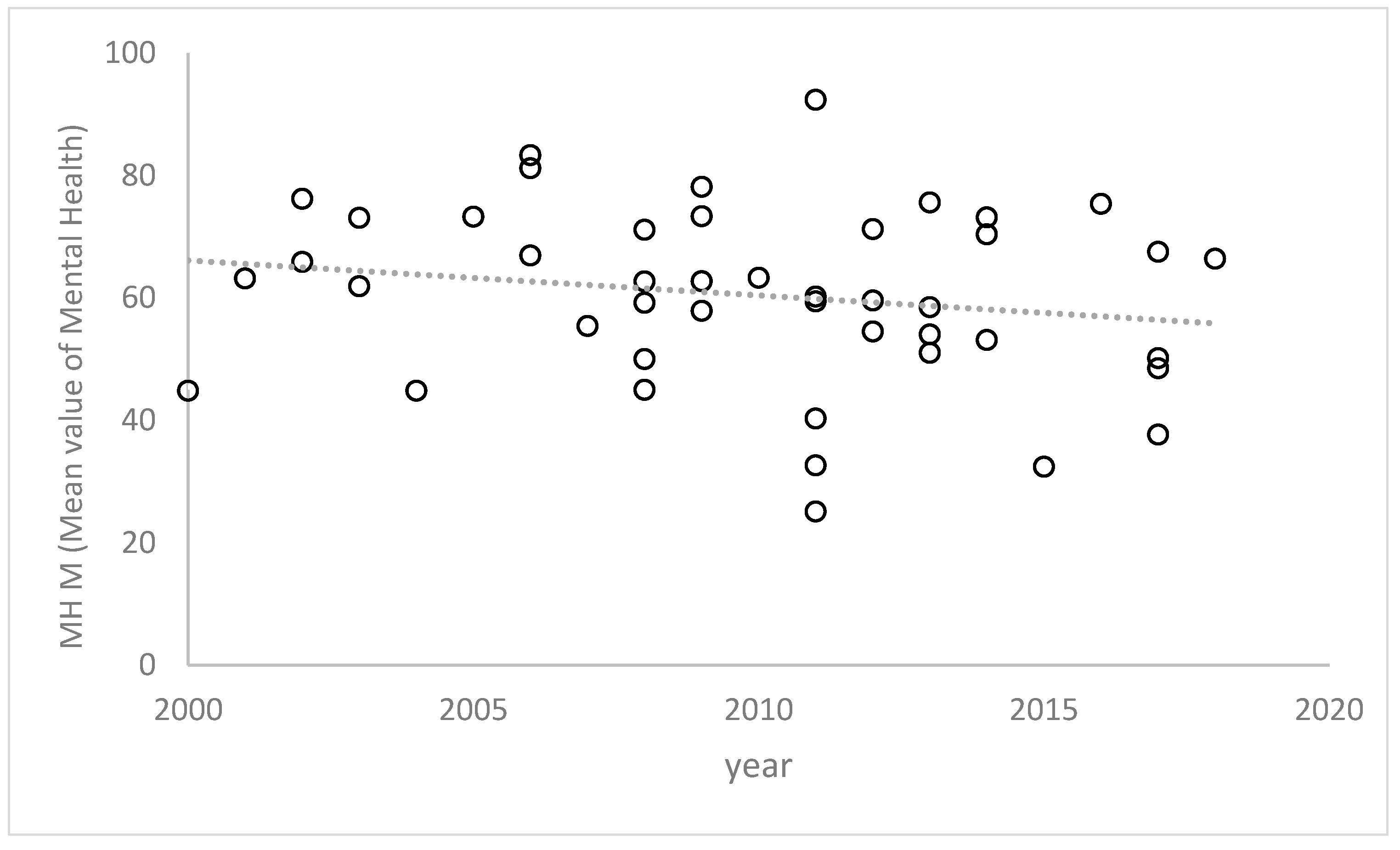

4.1. The HRQoL of the Elderly in China Has Risen in Some, but Fallen in Other, Indicators over 20 Years

In this study, we cross-temporally meta-analyzed 45 research reports on measuring the HRQoL of the elderly (36,352 subjects in total) in China with a SF-36 scale from 2002 to 2020. It was found that bodily pain, general health, vitality, and mental health decreased over the years, which may be related to the demographic and epidemiological shifts where the “inverted pyramid” family structure [

5] and the surge in non-communicable diseases [

4] degrade the HRQoL of the elderly. Urbanization has produced a large-scale rural–urban movement in China (a large number of young people move away from their homes to work in other places). This trend has also resulted in an increasing number of elderly people being left behind in rural areas. The rising number of “empty nesters” [

4] living alone [

38] further compromises the exercise of “filial piety” and, thus, the traditional Chinese intergenerational support system [

39]. The absence of children’s company may deplete the physical and mental health [

40,

41] and, therefore, the vitality and general health of the elderly.

However, with the advancement in information and communication technologies (ICTs) [

42], the “empty nesters” or the elderly people living alone can stay connected with their children and have relatively stable socio-emotional support. The use of smartphones by older people has a significant positive impact on subjective health, especially on mental health [

43]. Leveraging the strength of ICT as an enabler of family support and real-time connectivity may promote the social functioning and the emotional wellness of the elderly. Empirical studies have found that the use of mobile Internet applications (Apps), including WeChat, WeChat Moments, and mobile payment, can effectively promote the physical and mental health of the elderly. Further evidence shows that the elderly with lower education levels even benefit more from the use of these apps [

43].

Despite the inspiring results of the support of ICT for the elderly’s everyday lives, it is important to consider that the elderly may have some difficulties in using smart devices, such as smartphones, especially alone. Additionally, regional differences in ICT infrastructure development may also limit how beneficial ICT is to the elderly. Therefore, further study is necessary to first identify the challenges that the elderly living alone face in using ICT products, such as mobile phones and apps, to inform ways to address them. Second, research analysis of information technology infrastructure development, such as the Internet, especially in remote areas, is urgently needed. The findings of such studies may accelerate the transformation of the benefits of smartphones for the elderly by improving infrastructure in underserved areas to encourage ICT usage, thereby enhancing the elderly’s social functioning and emotional roles over time.

4.2. The Increasing Dependency Ratio of the Elderly Weakens Their HRQoL

As a social indicator, the dependency ratio of the elderly significantly correlates with the HRQoL of the elderly negatively. That is, the rising dependency ratio of the elderly in China implies a decline in the elderly’s HRQoL. This indicates that the social and family pension burden is heavier. Specifically, the implementation of the family planning policy (only-child policy) in the late 1970s has generated an aging population far larger than the population they depend on [

44]. Many families have a situation where one young family needs to raise children whilst supporting four elderly people. This may lead to two potential outcomes—first, the family’s support for the elderly may further decline and, second, institutional care may be chosen for the elderly. Either way, the HRQoL of the elderly, as evidenced in this meta-analysis, would be worse off.

To address this structural problem, the high dependency ratio of the elderly must be reduced to improve the HRQoL of the elderly. The adjustment in family planning in China is a step in the right direction. That is, the shift in the Government of China’s advocacy for “fewer and better” births to the current relaxation of childbirth, including the introduction of “two children” for couples who are the only children of their parents, to “two children” even if only one of the couple is the only child of his/her parents, and then to the universal “two-child policy”, regardless of whether a couple comprises only children or not, right to the current universal “three-child birth policy”, may remedy the rising dependency ratio. In this way, the support of the elderly can be shared by the children, and the life pressure on the children can be alleviated. This will be helpful in improving not only the HRQoL of the elderly but also that of the people they depend on. Future research that analyses whether the current birth policy is achieving the intended results is needed to forecast the dependency ratio for the foreseeable future and mitigation strategies.

4.3. The HRQoL of the Elderly under Home Care Is Higher Than That of Those under Institutional Care

Our findings indicate that the HRQoL of the elderly under home care mainly shows an improvement over time. This may be mainly because the elderly live with their children and/or spouses. The family economic conditions in China are better now than before. Therefore, families can now afford to nourish the elderly in terms of their bodies and make available relevant entertainment technologies for their emotional and mental well-being, improving their HRQoL [

45]. However, due to the “over-care” of the family, the subjective feelings of the elderly may be ignored and the energy of the elderly will be reduced, making them prone to fatigue [

46]. This is mainly reflected in the fact that the three factors of physical pain, vitality, and mental health show a downward trend over time. Family and environment play an important role in the care of the elderly in China [

47]. Since the development of institutional care for the elderly, the facilities have not been adequate, the relevant systems have been lacking, and the institutions have only been able to provide basic living services without family care. These basic services are too poor in quality and quantity to be able to cater to the mental and emotional needs of the elderly [

3,

4]. Therefore, we notice that all of the indicators of the HRQoL of the elderly who are under institutional care have greatly declined over time. These results are consistent with prior research that the aged who live with their family are less depressed than those who do not [

38].

For the home-based care model, children should pay more attention to their physical pain, vitality, and mental health, such as by providing better medical services, improving the energy of the elderly, and caring for the spiritual needs of the elderly, so as to improve the quality of life of the elderly. For the institutional pension model, the government actively supports and supervises, promotes the elderly care institutions to continuously strengthen hardware and software investment, and improves the level of elderly care services. Elderly care institutions themselves should take the initiative to improve their hardware and software levels to promote the high-quality development of elderly care services. It is also necessary to build a comprehensive talent training and service quality evaluation system for elderly care institutions. Considering the differences in the elderly HRQoL between the elderly under institutional care and those in the home-based care model, future research that examines the details of how the elderly live under these two models may reveal insights that may be beneficial for improving HRQoL of the elderly.

4.4. The Elderly’s HRQoL Indicators Have All Declined in Underdeveloped Areas but Show Mixed Results in Developed Ones

The results of our CTMA also support the literature evidence that the HRQoL of the elderly varies across regions—developed and underdeveloped [

23,

48]. The findings show that physical functioning, role-physical, overall health, and social functioning in developed areas are on an upward trend. With continuous investments, the medical conditions in economically developed areas are getting better and better; however, the medical resources in economically underdeveloped areas are relatively scarce [

4]. The elderly in economically developed areas have better medical treatments, relatively complete service facilities, and social networks [

15,

23]. The elderly in economically developed areas typically have the capacity to meet their material needs; so, they pay more attention to their emotional and mental health needs [

15]. However, all factors in underdeveloped areas show a downward trend over time. This may be because the rural family structure is undergoing structural changes with the rural–urban migration [

18,

49].

Due to the restrictions of the household registration system and the high cost of health and education services in cities, most migrant workers leave their children in their hometowns to be taken care of by their parents. However, when the left-behind elderly live with their grandchildren, they not only have to farm but also undertake the tasks of care and education for their grandchildren, which increases the physical and mental burden of the elderly. Moreover, most of the elderly people in economically underdeveloped areas are generally not well educated and, therefore, lack awareness of modern educational methods. They often feel inadequate in educating their grandchildren and feel worried that they may be blamed for their grandchildren’s failure to make it in life. In addition, because children are no longer around for a long time, the elderly often lack the tender care of their children. Lack of family comfort leads to a strong sense of loneliness [

50], which affects the HRQoL of the elderly. Therefore, the rural areas in economically underdeveloped areas mainly pay attention to survival-oriented old-age resources while the elderly in rural areas in economically developed areas mainly pay attention to development-oriented resources for the age. Future research that explores the intricate details of the specific activities, events, resources, and access that condition differences in elderly HRQoL in developed and underdeveloped areas would be a useful starting point in helping those in underdeveloped areas.

5. Limitations

In spite of the theoretical and practical implications of this study, a number of limitations are worth mentioning. First, our results on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of the elderly in China over a 20-year period were obtained through a cross-temporal meta-analysis of 45 studies that used the SF-36 scale. This scale assesses individual physical and mental factors but does not cover individual cognition, consciousness, etc. The dimensional limitation of this scale limits the scope of generalizability of the research results. Therefore, there is a need to examine other scales that measure other dimensions of elderly quality of life, including the PERMA or PANAS models. Second, our analysis did not account for key demographic characteristics of the elderly that may be informative, such as the economic status of the elderly, whether they are single, and whether they are migrant elderly following their children. This limits the contextual relevance of our analytical results beyond the general trends. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies should pay attention to how the quality of life of the elderly differs across socio-demographic characteristics. Such a deep analysis may reveal ways interventions may be most effective and useful.