Influential Factors Affecting Tea Tourists’ Behavior Intention in Cultural Ecosystem Services: An Affordance Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

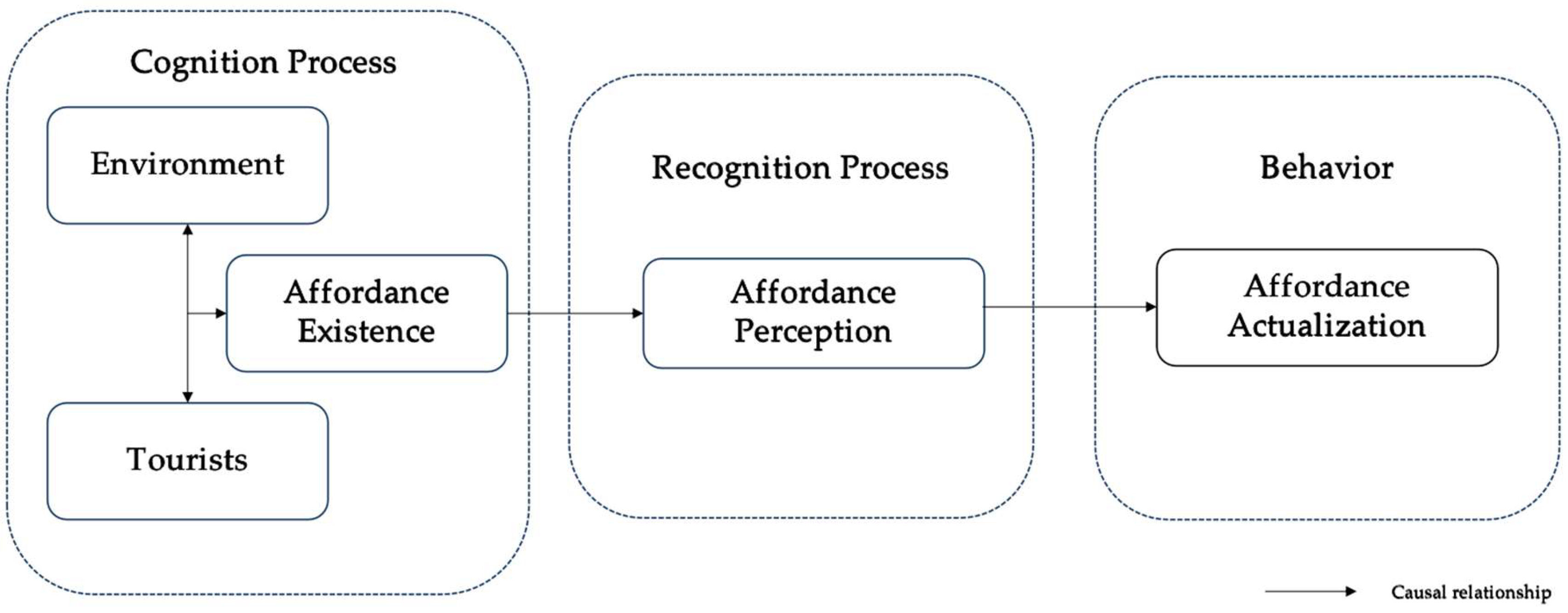

2.1. Affordance Theory in the Tourism Environment

2.2. Tourists’ Behavior in Tea Tourism and Its Influencing Factors

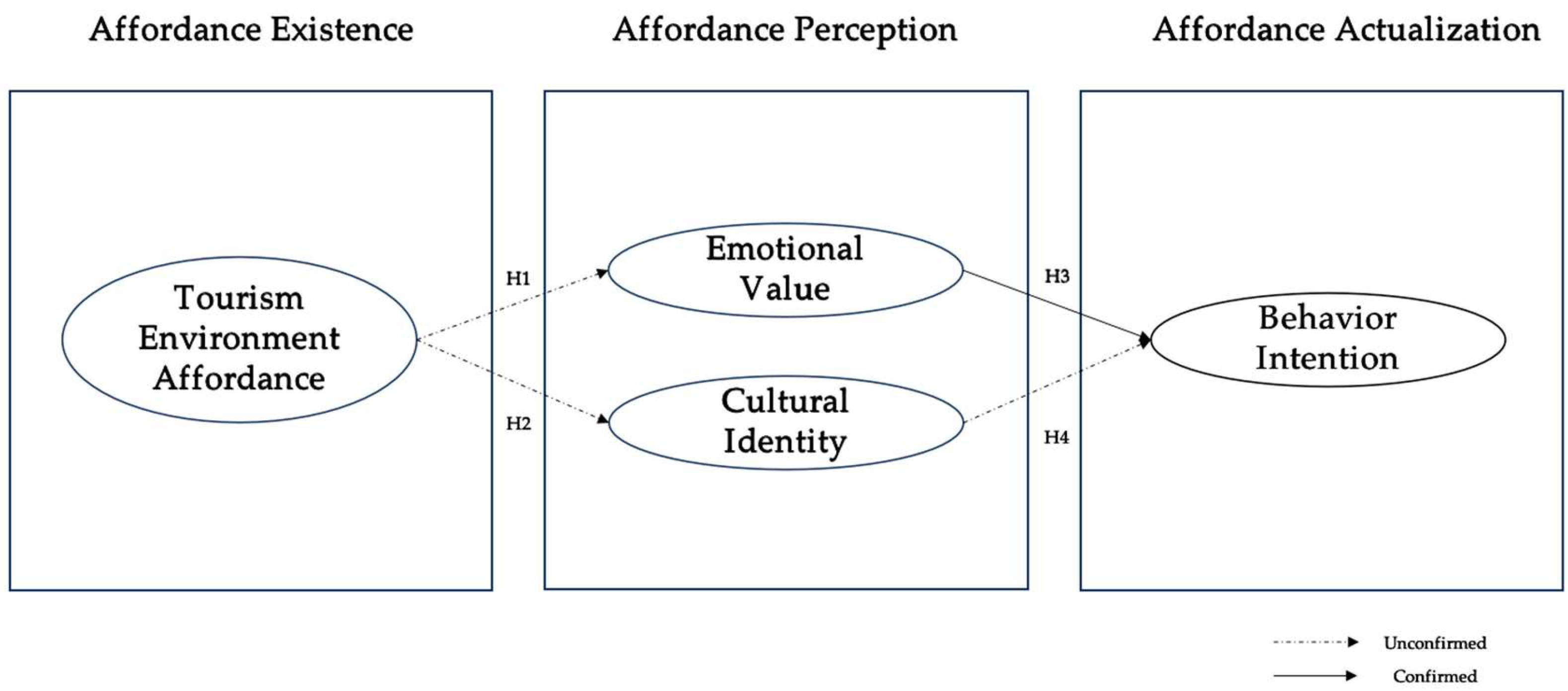

2.3. Hypothesis Development

2.3.1. Tourism Environment Affordance and Affordance Perception

2.3.2. Affordance Perception and Behavior Intention

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

3.2. Structural Equation Model Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Equation Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Applying Affordance Theory in Tea Tourism Context

5.2. Implication for Tea Tourism

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.; Whitford, M.; Arcodia, C. Development of Intangible Cultural Heritage as a Sustainable Tourism Resource: The Intangible Cultural Heritage Practitioners’ Perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, G.; Dixit, S.K. Analyzing Tea Tourism Products and Experiences from India and Turkey: Supply Proclivities. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2023, 71, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Chinese Tea Culture; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, I. Tea for Tourists: Cultural Capital, Representation, and Borrowing in the Tea Culture of Mainland China and Taiwan. Acad. Tur.-Tour. Innov. J. 2018, 11, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICHChina. Basking in the Radiant Spring Light: Embarking on a Journey to the Tea Mountains. 2022. Available online: https://www.ihchina.cn/news_1_details/27040.html (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Milcu, A.I.; Hanspach, J.; Abson, D.; Fischer, J. Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Literature Review and Prospects for Future Research. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Tengö, M.; McPhearson, T.; Kremer, P. Cultural Ecosystem Services as a Gateway for Improving Urban Sustainability. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, L. Tea and Tourism: Tourists, Traditions and Transformations; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y. Integrating Tea and Tourism: A Sustainable Livelihoods Approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1591–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zheng, X.; Meng, F.; Zhang, X. The Evolution of Cultural Space in a World Heritage Site: Tourism Sustainable Development of Mount Wuyi, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhu, K.; Kang, L.; Dávid, L.D. Tea Culture Tourism Perception: A Study on the Harmony of Importance and Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Samaddar, K. Exploring the Current Issues, Challenges and Opportunities in Tea Tourism: A Morphological Analysis. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 15, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, Q. Destination Image, Nostalgic Feeling, Flow Experience and Agritourism: An Empirical Study of Yunling Tea Estate in Anxi, China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 954299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-H.; Lai, I.K.W. Tea Tourism: Designation of Origin Brand Image, Destination Image, and Visit Intention. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 29, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.I.; Lim, X.-J.; Hall, C.M.; Tee, K.K.; Basha, N.K.; Ibrahim, W.S.N.B.; Naderi Koupaei, S. Time for Tea: Factors of Service Quality, Memorable Tourism Experience and Loyalty in Sustainable Tea Tourism Destination. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanin, Y.; Boonying, K. Sustainable Livelihood and Revisit Intention for Tea Tourism Destinations: An Application of Theory of Reasoned Action—ProQuest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/81188ead2cb9285d53d65d7fe6d6b0f6/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29726 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Raymond, C.M.; Kyttä, M.; Stedman, R. Sense of Place, Fast and Slow: The Potential Contributions of Affordance Theory to Sense of Place. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohne, H. Uniqueness of Tea Traditions and Impacts on Tourism: The East Frisian Tea Culture. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 15, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Cros, H. A New Model to Assist in Planning for Sustainable Cultural Heritage Tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Sustainability of Heritage Tourism: A Structural Perspective from Cultural Identity and Consumption Intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Chemero, A. An Outline of a Theory of Affordances. Ecol. Psychol. 2003, 15, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkoff, O.; Strong, D.M. Critical Realism and Affordances: Theorizing It-Associated Organizational Change Processes. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, E.; Recker, J.; Burton-Jones, A. Understanding the Actualization of Affordances: A Study in the Process Modeling Context. In ICIS 2013 Proceedings, Milan, Italy, 15–18 December 2023; AIS eLibrary: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi, G.; Pigni, F.; Vitari, C. Affordance Theory in the IS Discipline: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature. In AMCIS 2014 Proceedings, Savannah, GA, USA, 7–9 August 2014; HAL Open Science: Lyon, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, Q. A Review of Application of Affordance Theory in Information Systems. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2018, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Akhoundogli, M. Tourism Affordances as a Research Lens. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiddu, F.; Carlo, M.D.; Piccoli, G. Social Media Affordances: Enabling Customer Engagement. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.I.; Wang, D.; Law, R. Perceived Technology Affordance and Value of Hotel Mobile Apps: A Comparison of Hoteliers and Customers. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Leung, W.K.S.; Munelli, F. Gamification in OTA Platforms: A Mixed-Methods Research Involving Online Shopping Carnival. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareither, C. Capture the Feeling: Memory Practices in between the Emotional Affordances of Heritage Sites and Digital Media. Mem. Stud. 2021, 14, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Tourism, Technology and ICT: A Critical Review of Affordances and Concessions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azinuddin, M.; Mohammad Nasir, M.B.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Mior Shariffuddin, N.S.; Kamarudin, M.K.A. Interlinkage of Perceived Ecotourism Design Affordance, Perceived Value of Destination Experiences, Destination Reputation, and Loyalty. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarn, J.L.M. The Effects of Service Quality, Perceived Value and Customer Satisfaction on Behavioral Intentions. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1999, 6, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience Quality, Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions for Heritage Tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesenmaier, D.R.; Xiang, Z. Introduction to Tourism Design and Design Science in Tourism. In Design Science in Tourism: Foundations of Destination Management; Tourism on the Verge; Fesenmaier, D.R., Xiang, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to the Visual Perception of Pictures. In The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, D.M.; Volkoff, O.; Johnson, S.A. A Theory of Organization-EHR Affordance Actualization. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/jais/vol15/iss2/2/ (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Norman, D.A. The Design of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, J. Two Visual Systems and Two Theories of Perception: An Attempt to Reconcile the Constructivist and Ecological Approaches. Behav. Brain Sci. 2002, 25, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M. Affordances of Children’s Environments in The Context of Cities, Small Towns, Suburbs and Rural Villages in Finland and Belarus. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Shi, Y.; Chen, R. Environmental Affordances and Children’s Needs: Insights from Child-Friendly Community Streets in China. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 12, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Weaven, S.; Wong, I.A. Linking AI Quality Performance and Customer Engagement: The Moderating Effect of AI Preference. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Gong, X. Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Platform Affordance: Scale Development and Empirical Investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 922–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Benckendorff, P.; Wang, J. Travel Live Streaming: An Affordance Perspective. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2021, 23, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Ren, G.; Hong, T.; Nam, K.; Koo, C. An Exploratory Analysis of Travel-Related WeChat Mini Program Usage: Affordance Theory Perspective. In Proceedings of the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, Nicosia, Cyprus, 30 January–1 February 2019; Pesonen, J., Neidhardt, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva, K.; Kane, G.C. Relational Affordances of Information Processing on Facebook. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wei, S.; Davison, R.M.; Rice, R.E. How Do Enterprise Social Media Affordances Affect Social Network Ties and Job Performance? Inf. Technol. People 2020, 33, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, T. Social Tie Formation in Chinese Online Social Commerce: The Role of IT Affordances. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 42, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bærenholdt, J.O.; Haldrup, M.; Urry, J. Performing Tourist Places; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Tang, X.; Luo, Y. Affordances of Scenic Cycleways: How Recreational Cyclists Interact with Different Environments. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, J.W. Meaning-Making in the Course of Action: Affordance Theory at the Pilgrim/Tourist Nexus. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghini, S.; Sherry, J.F.; Joy, A. Attachment to and Detachment from Favorite Stores: An Affordance Theory Perspective. J. Consum. Res. 2021, 47, 890–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Hu, J.; Fox, D.; Zhang, Y. Tea Tourism Development in Xinyang, China: Stakeholders’ View. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 2–3, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimanche, F.; Havitz, M.E. Consumer Behavior and Tourism: Review and Extension of Four Study Areas. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1995, 3, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; La, S. What Influences the Relationship between Customer Satisfaction and Repurchase Intention? Investigating the Effects of Adjusted Expectations and Customer Loyalty. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Lee, C.-K.; Choi, Y. Examining the Role of Emotional and Functional Values in Festival Evaluation. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0047287510385465 (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Tomej, K.; Xiang, Z. Affordances for Tourism Service Design. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu Quynh, N.; Tran Chi, T. Factors Affecting Tourist Satisfaction with Traditional Craft Tea Villages in Thai Nguyen Province. J. Econ. Dev. 2019, 21, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Nguyen, H.V.; Chou, T.P.; Chen, C.-P. A Comprehensive Model of Consumers’ Perceptions, Attitudes and Behavioral Intention toward Organic Tea: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Han, H. Role of Halal-Friendly Destination Performances, Value, Satisfaction, and Trust in Generating Destination Image and Loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Lee, C.-K.; Park, J.A.; Hwang, Y.H.; Reisinger, Y. The Influence of Tourist Experience on Perceived Value and Satisfaction with Temple Stays: The Experience Economy Theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavluković, V.; Armenski, T.; Alcántara-Pilar, J.M. Social Impacts of Music Festivals: Does Culture Impact Locals’ Attitude toward Events in Serbia and Hungary? Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J.; Calcagni, F.; Baró, F. Mapping the Intangible: Using Geolocated Social Media Data to Examine Landscape Aesthetics. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C. Tourism and the Symbols of Identity. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.C. Rukai Indigenous Tourism: Representations, Cultural Identity and Q Method. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vena-Oya, J.; Castañeda-García, J.A.; Rodríguez-Molina, M.Á.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M. How Do Monetary and Time Spend Explain Cultural Tourist Satisfaction? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volo, S. The Experience of Emotion: Directions for Tourism Design. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The Role of Tourists’ Emotional Experiences and Satisfaction in Understanding Behavioral Intentions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Cristóvão Veríssimo, J.M.; de Oliveira, J.C.L. Memorable Tourism Experiences, Perceived Value Dimensions and Behavioral Intentions: A Demographic Segmentation Approach. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 1472–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Rather, R.A.; Hall, C.M. Investigating the Mediating Role of Visitor Satisfaction in the Relationship between Memorable Tourism Experiences and Behavioral Intentions in Heritage Tourism Context. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, G.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Morrison, A.M. Red Tourism in China: Emotional Experiences, National Identity and Behavioural Intentions. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 1037–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.; Correia, A.; Filipe, J.A. Modelling Wine Tourism Experiences. Anatolia 2019, 30, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism Applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Kang, Y.; Hong, L.; Huang, Y. Can Cultural Tourism Experience Enhance Cultural Confidence? The Evidence from Qingyuan Mountain. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1063569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural Tourism: An Analysis of Engagement, Cultural Contact, Memorable Tourism Experience and Destination Loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistics Notes: Cronbach’s Alpha. BMJ 1997, 314, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, N. A Mathematical Analysis of the Evolution of Human Mate Choice Traits: Implications for Evolutionary Psychologists. J. Evol. Psychol. 2011, 9, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. E-Collab. Ijec 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and Validity Assessment; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Eisinga, R.; Grotenhuis, M.T.; Pelzer, B. The Reliability of a Two-Item Scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Song, Y.M.; Gim, G.Y. Factors Affecting the Intention to Use Artificial Intelligence-Based Recruitment System: A Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligence Science, Durgapur, India, 24–27 February 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, W.; Cundy, A.B.; Chang, A.C.; Jiao, W. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Public Perception in Contaminated Site Management: Simulation by Structural Equation Modeling at Four Sites in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 210, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, T.-H.T. Comparing Happiness Determinants for Urban Residents a Partial Least Squares Regression Model. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 9, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Wang, E.T. Understanding Web-Based Learning Continuance Intention: The Role of Subjective Task Value. Inf. Manage. 2008, 45, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, S.J. Book Review: Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications: By Bruce Thompson Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2004, 195 Pp., $49.95 (Hardcover) ISBN 1-59147-093-5. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 2007, 31, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jafar, R.M.S.; Morley-Bunker, M.; Lin, C.; Chen, L.; Wu, R.; Zhuang, P. On the Marketing Mix of Fujian Tea Tourism; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.; Callarisa, L.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Moliner, M.A. Perceived Value of the Purchase of a Tourism Product. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-C. Tea for Well-Being: Restaurant Atmosphere and Repurchase Intention for Hotel Afternoon Tea Services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Toppinen, A.; Wang, L. Cultural Motives Affecting Tea Purchase Behavior under Two Usage Situations in China: A Study of Renqing, Mianzi, Collectivism, and Man-Nature Unity Culture. J. Ethn. Foods 2021, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Amri, D.; Akrout, H. Perceived Design Affordance of New Products: Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Ben-Nun, L. The Important Dimensions of Wine Tourism Experience from Potential Visitors’ Perception. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, L.-H.; Su, P.; Morrison, A.M. The Right Brew? An Analysis of the Tourism Experiences in Rural Taiwan’s Coffee Estates. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Qiu, H.; King, B.E.; Huang, S. Understanding the Wine Tourism Experience: The Roles of Facilitators, Constraints, and Involvement. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Jian, Y.; Fu, H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M. Vernacular or Modern: Transitional Preferences of Residents Living in Varied Stages of Urbanisation Regarding Rural Landscape Features. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, J.A. Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Hinch, T.; Ingram, T. Cultural Identity and Tourism. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2002, 4, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Wang, Z.; Jie, H.; Wang, L. Emotional Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Urban Park Users: A Case Study of South China Botanical Garden and Yuexiu Park. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao 2021, 57, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation: Environment, Place and Space; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe, J. The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brochado, A.; Stoleriu, O.; Lupu, C. Wine Tourism: A Multisensory Experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, H. Producing an Ideal Village: Imagined Rurality, Tourism and Rural Gentrification in China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Berbekova, A.; Uysal, M.; Wang, J. Emotional Solidarity and Co-Creation of Experience as Determinants of Environmentally Responsible Behavior: A Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory Perspective. J. Travel Res. 2022, 00472875221146786. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/00472875221146786 (accessed on 4 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. The Role of the Rural Tourism Experience Economy in Place Attachment and Behavioral Intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism Environment Affordance | 0.878 | 0.590 | ||

| TAE1: There are events, shows, performances of tea-related culture. | 4.088 | 0.749 | ||

| TAE2: The experience stimulated my curiosity about tea. | 4.041 | 0.781 | ||

| TAE3: The environment showed attention to detail design. | 3.784 | 0.763 | ||

| TAE4: The staff were professional. | 3.818 | 0.749 | ||

| TAE5: The transportation and facilities there are convenient. | 4.047 | 0.800 | ||

| Emotional Value | 0.849 | 0.737 | ||

| EV1: Visiting the tea tourism site was pleasurable. | 3.855 | 0.859 | ||

| EV2: Tea tourism experience is one that I would feel relaxed. | 3.838 | 0.859 | ||

| Cultural Identity | 0.846 | 0.733 | ||

| CI1: I am proud of our Chinese tea culture. | 3.720 | 0.857 | ||

| CI2: Our country has a profound history of tea. | 3.649 | 0.857 | ||

| Behavior Intention | 0.843 | 0.729 | ||

| BI1: I tent to revisit this tea tourism site in the future. | 3.713 | 0.854 | ||

| BI2: I would like to purchase tea-related products and services. | 3.767 | 0.854 |

| Tourism Environment Affordance | Behavior Intention | Cultural Identity | Emotional Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism Environment Affordance | 0.699 | |||

| Behavior Intention | 0.357 | 0.689 | ||

| Cultural Identity | 0.248 | 0.534 | 0.686 | |

| Emotional Value | 0.288 | 0.560 | 0.521 | 0.678 |

| Name | Judgment Criterion | Results |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | <3 | 1.063 |

| RMR | <0.10 | 0.033 |

| RMSEA | <0.10 | 0.009 |

| IFI | >0.9 | 0.998 |

| TLI | >0.9 | 0.996 |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.997 |

| NFI | >0.9 | 0.960 |

| NNFI | >0.9 | 0.996 |

| Name | Judgment Criterion | Results |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | <3 | 2.776 |

| RMR | <0.10 | 0.985 |

| RMSEA | <0.10 | 0.078 |

| IFI | >0.9 | 0.928 |

| TLI | >0.9 | 0.900 |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.926 |

| NFI | >0.9 | 0.920 |

| NNFI | >0.9 | 0.900 |

| Model Path | Coefficient | SE | CR | p | Standardized Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAE→EV | 0.549 | 0.096 | 5.723 | *** | 0.502 |

| TAE→CI | 0.358 | 0.088 | 4.057 | *** | 0.367 |

| EV→BI | 0.617 | 0.103 | 5.976 | *** | 0.639 |

| CI→BI | 0.543 | 0.105 | 5.182 | *** | 0.501 |

| TAE1←TAE | 1 | 0.669 | |||

| TAE2←TAE | 1.08 | 0.106 | 10.2 | *** | 0.717 |

| TAE3←TAE | 1.112 | 0.113 | 9.848 | *** | 0.686 |

| TAE4←TAE | 1.079 | 0.111 | 9.731 | *** | 0.676 |

| TAE5←TAE | 1.114 | 0.107 | 10.39 | *** | 0.735 |

| EV1←EV | 1 | 0.677 | |||

| EV2←EV | 1.067 | 0.142 | 7.529 | *** | 0.712 |

| CI1←CI | 1 | 0.584 | |||

| CI2←CI | 1.461 | 0.25 | 5.839 | *** | 0.811 |

| BI1←BI | 1 | 0.624 | |||

| BI2←BI | 1.033 | 0.131 | 7.894 | *** | 0.681 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, L.; Xiong, C.; Xu, M. Influential Factors Affecting Tea Tourists’ Behavior Intention in Cultural Ecosystem Services: An Affordance Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115503

Fu L, Xiong C, Xu M. Influential Factors Affecting Tea Tourists’ Behavior Intention in Cultural Ecosystem Services: An Affordance Perspective. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115503

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Lingbo, Chengyu Xiong, and Min Xu. 2023. "Influential Factors Affecting Tea Tourists’ Behavior Intention in Cultural Ecosystem Services: An Affordance Perspective" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115503

APA StyleFu, L., Xiong, C., & Xu, M. (2023). Influential Factors Affecting Tea Tourists’ Behavior Intention in Cultural Ecosystem Services: An Affordance Perspective. Sustainability, 15(21), 15503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115503