Travelers’ (in)Resilience to Environmental Risks Emphasized in the Media and Their Redirecting to Medical Destinations: Enhancing Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Environmental Risks and Tourists’ Intents to Visit Safer Medical Destinations

2.2. The Impact of the Media on How Tourists Behave

3. Methodology

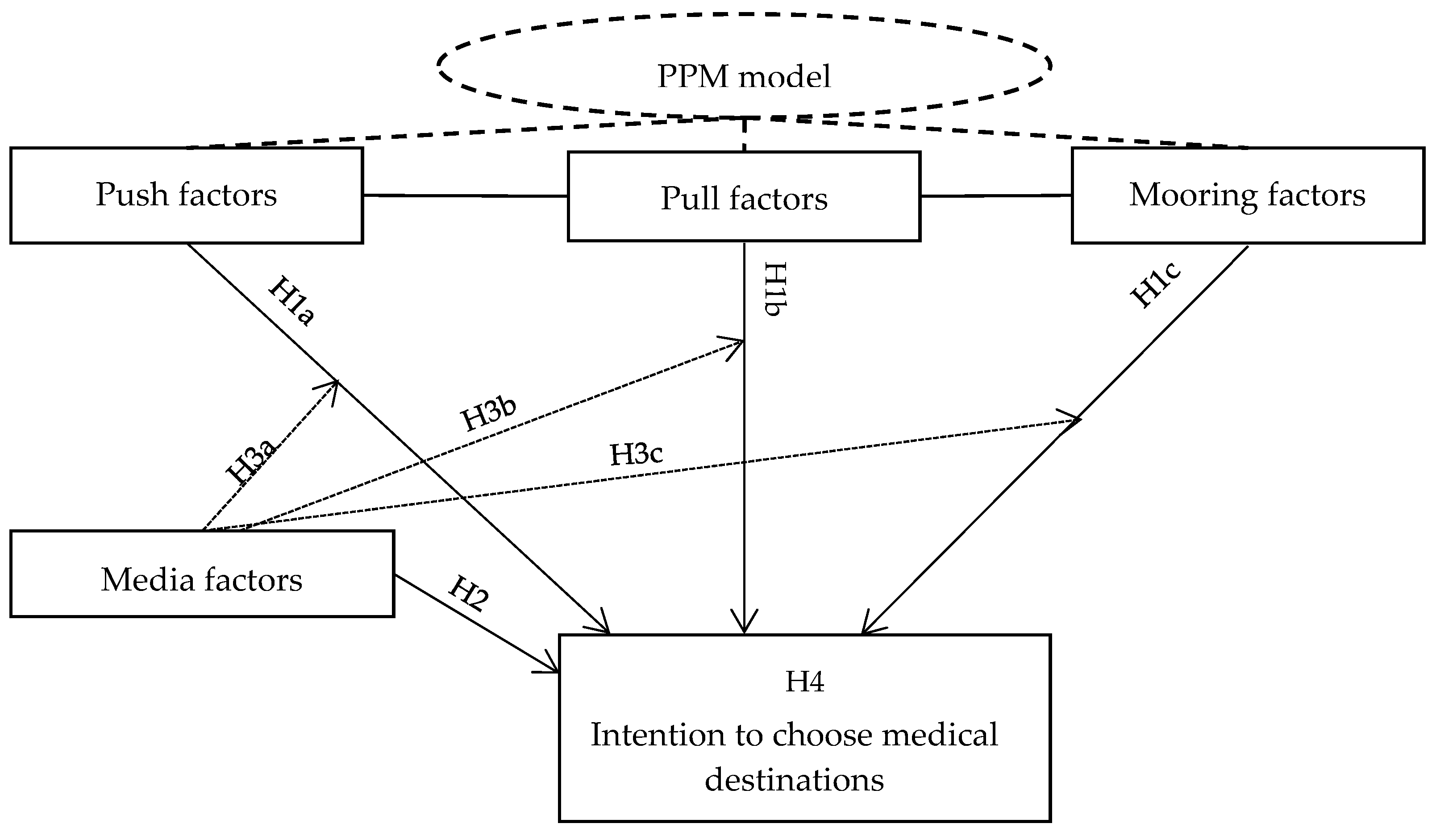

3.1. Modeling of Research Objectives and Hypotheses

3.2. Research Method and Questionaire Design

3.3. Measurements

3.4. Research Context: Spatial Setting and Participants

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

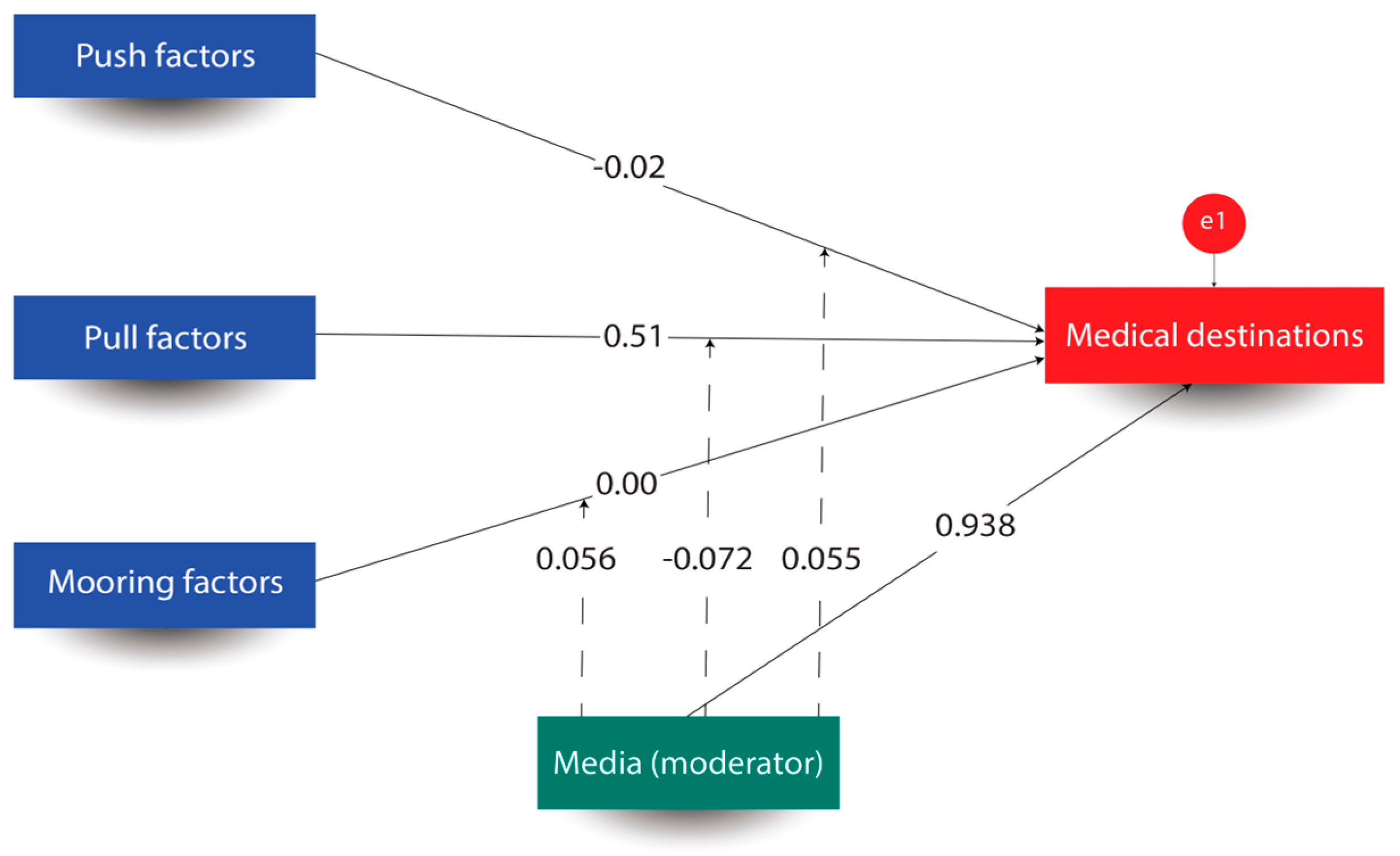

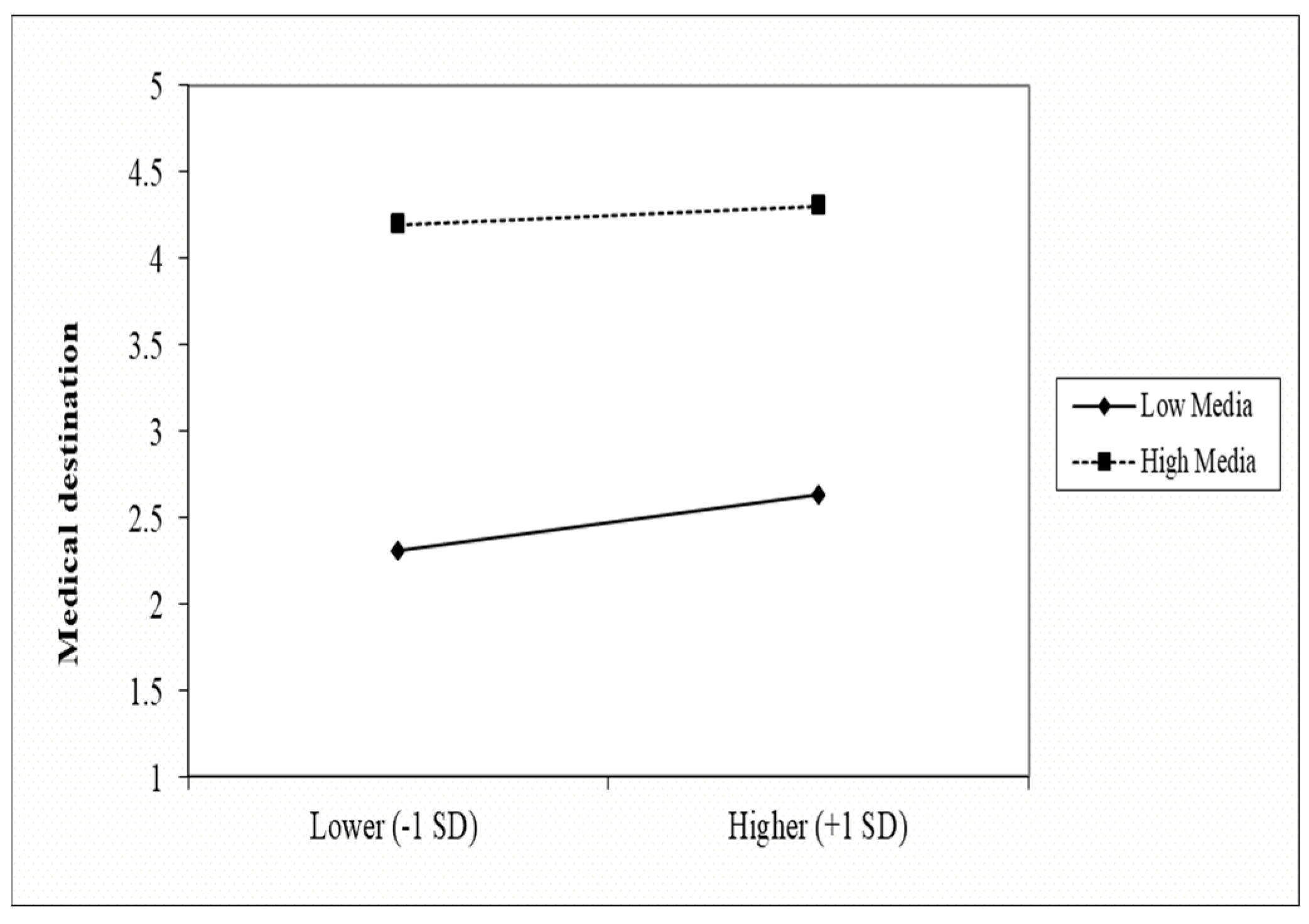

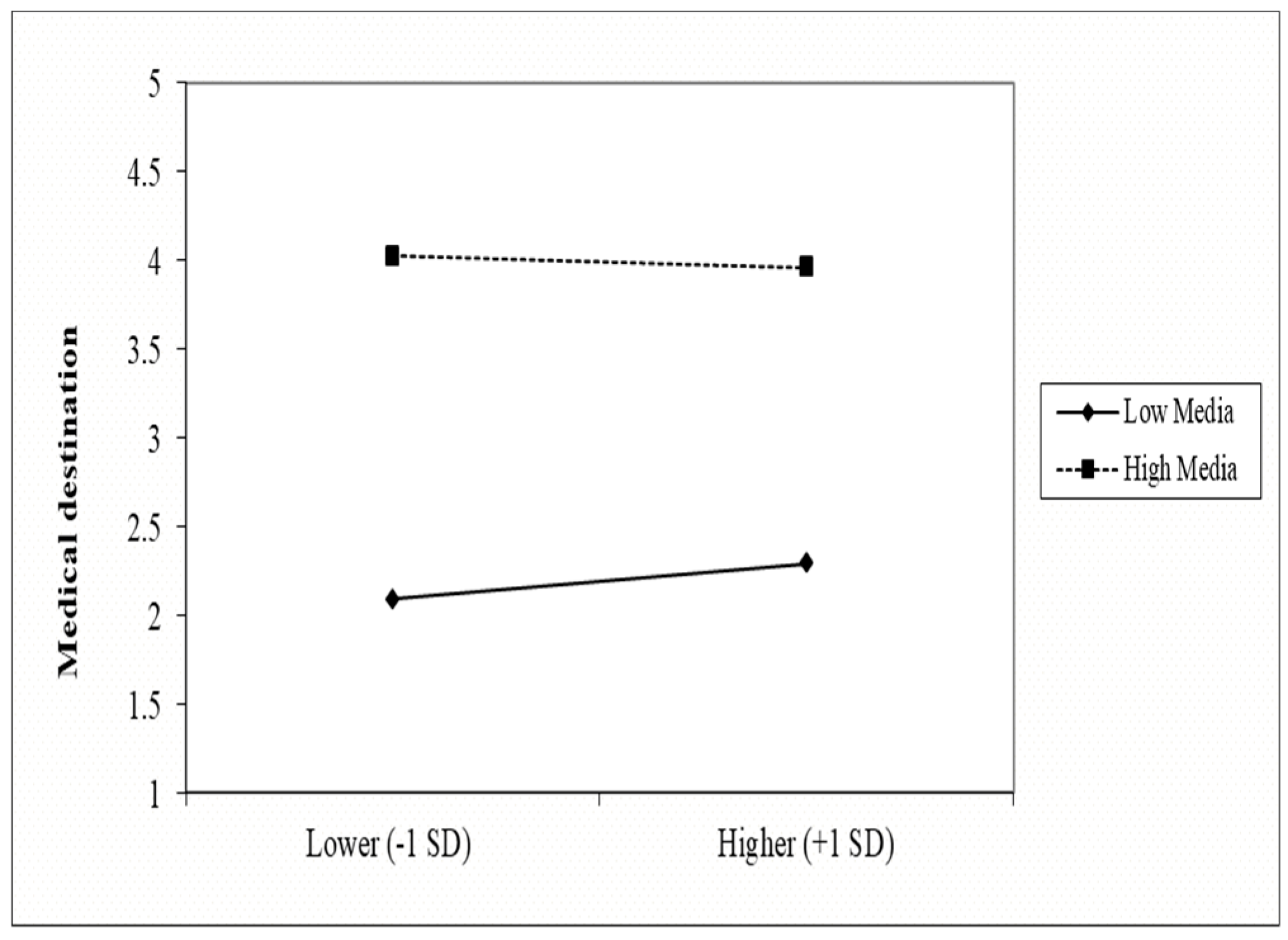

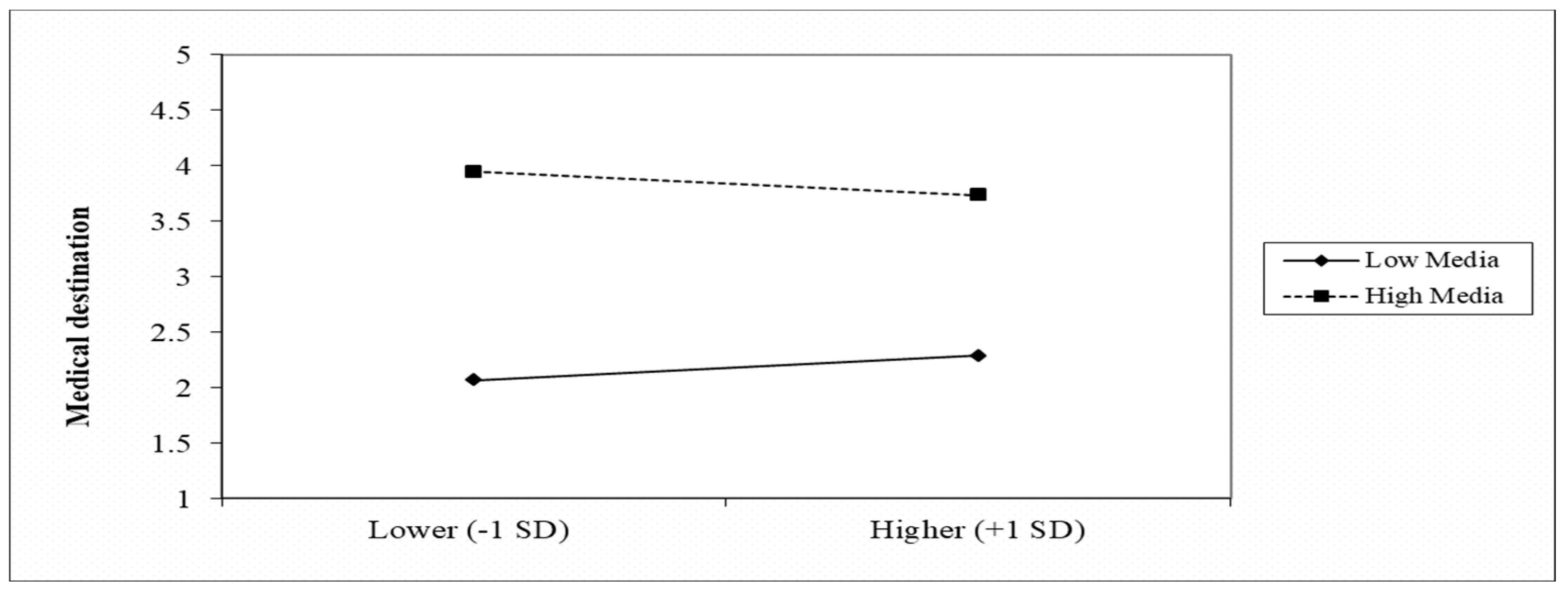

4.1. Results of Moderating Path Analysis

4.2. Results of Multinominal Logistic Regression

5. Discussion of Findings and Concluding Remarks

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Managerial Insights Focused on Sustainability

5.3. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, K.; Hou, Y.; Li, G. Threat of infectious disease during an outbreak: Influence on tourists’ emotional responses to disadvantaged price inequality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, J.I. The impacts of state growth management programmes: A comparative analysis. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 1959–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Prideaux, B.; Cheung, C.; Law, R. Achieving voluntary reductions in the carbon footprint of tourism and climate change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, L.; Di Virgilio, F.; Pantano, E. Social Network for the Choice of Tourist Destination: Attitude and Behavioural Intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2012, 3, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.Z. A hybrid Fifth Generation based approaches on extracting and analyzing customer requirement through online mode in healthcare industry. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 106, 108550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivac, T.; Blešić, I.; Kovačić, S.; Besermenji, S.; Lesjak, M. Visitors’ satisfaction, perceived quality, and behavioral intentions: The case study of exit festival. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic 2019, 69, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedova, N.N.; Minasyan, L.A.; Shchekin, G.Y.; Tabatadze, G.S.; Kostenko, O.V. Russian healthcare in the development of medical tourism. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 273, 09003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Feng, F.; Wu, Y. Exploring key factors of medical tourism and its relation with tourism attraction and revisit intention. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1746108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.G.; Zhang, Y.J. Medical tourism: Literature review and research prospects. Tour. Trib. 2016, 6, 113–126. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20163230879 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Skountridaki, L. Barriers to business relations between medical tourism facilitators and medical professionals. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Review on the definitions and concept of tourism currently popular in the world—Recognition of the nature of tourism. Tour. Trib. 2008, 23, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Symbiotic relationship or not? Understanding resilience and crisis management in tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Nørfelt, A.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G.; Tsionas, M.G. Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The Evolutionary Tourism Paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.N.; Farooq, A.; Dhir, A. Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A.D.A.M.; Borgers, A.W.J.; Timmermans, H.J.P. A semi-parametric hazard model of activity timing and sequencing decisions during visits to theme parks using experimental design data. Tour. Anal. 2002, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H.K.; Lee, T.J.; Yoon, Y.-S. Relationship between perceived risk, evaluation, satisfaction, and behavioral intention: A caseof local-festival visitors. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Ismail, A.R.; Islam, M.F. Tourist risk perceptions and revisit intention: A critical review of literature. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1412874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.H.; Wu, T.; Wall, G.; Linliu, S.C. Perceptions of tourism impacts and community resilience to natural disasters. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghavvemi, S.; Ormond, M.; Musa, G.; Isa, C.R.M.; Thirumoorthi, T.; Mustapha, M.Z.B.; Kanapathy, K.A.P.; Chandy, J.J. Connecting with prospective medical tourists online: A cross-sectional analysis of private hospital websites promoting medical tourism in India, Malaysia and Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.L.; Oviedo, N. Medical Tourism: A SWOT Analysis of Mexico and the Philippines. 2013. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2234866 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Amutha, D. Booming Medical Tourism in India. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2234028 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Wang, F.; Xue, T.; Wang, T.; Wu, B. The mechanism of tourism risk perception in severe epidemic—The antecedent effect of place image depicted in anti-epidemic music videos and the moderating effect of visiting history. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Milovanović, I.; Gajić, T.; Kholina, V.N.; Vujičić, M.; Blešić, I.; Ðoković, F.; Radovanović, M.M.; Ćurčić, N.B.; Rahmat, A.F.; et al. The Degree of Environmental Risk and Attractiveness as a Criterion for Visiting a Tourist Destination. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Pateli, A. Information technology-enabled dynamic capabilities and their indirect effect on competitive performance: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantopoulos, I.; Vicky, K.; Mary, G. A Supply Side Investigation of Medical Tourism and ICT Use in Greece. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Kamar, M.S.A.; Onjewu, A.K.E.; Soliman, M. Evaluating the Antecedents of Health Destination Loyalty: The Moderating Role of Destination Trust and Tourists’ Emotions. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2023, 24, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Koo, C. The Use of Social Media in Travel Information Search. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, R. Catastrophe of Environment: The Impact of Natural Disasters on Tourism Industry. J. Tour. Adventure 2018, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, E. Natural disasters and social capital formation: The impact of the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2021, 95, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtin, V.A. Ethnocultural aspects of improving the tourist support of medical tourism. Sociodynamics 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.; Crooks, V.A.; Ormond, M. Policy implications of medical tourism development in destination countries: Revisiting and revising an existing framework by examining the case of Jamaica. Glob. Health 2015, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X. Legal and policy suggestions on developing international medical tourism industry in China. Med. Jurisprud. 2012, 4, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikke, S.; Despena, A. American medical tourism in India: A retrospective health policy analysis. Int. J. Responsible Tour. 2015, 4, 33–50. Available online: https://findresearcher.sdu.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/120770452/15_health_tourism.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Rosselló, J.; Becken, S.; Santana-Gallego, M. The effects of natural disasters on international tourism: A global analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 79, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prüss-Ustün, A. Environmental risks and non-communicable diseases. BMJ 2019, 365, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roudini, J.; Khankeh, H.; Witruk, E. Disaster mental health preparedness in the community: A systematic review study. HealthPsychol. Open 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Mitsche, N.; Hwang, Y.H.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Tell me who you are and I will tell you where to go: Use of travel personalities in destination recommendation systems. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2004, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Sutherland, L.A. Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism: Implications for the design of powerful interpretive experiences. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Gajić, T.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A.; Radovanović, M.; Popov-Raljić, J.; Yakovenko, N.V. How the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Can be Applied in the Research of the Influencing Factors of Food Waste in Restaurants: Learning from Serbian Urban Centers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeyeva, A.M.; Omirzakova, M.Z.; Zhakuda, G.N.; Telekeshov, K.A. Territorial image and branding as tools for developing western Kazakhstan as a tourist destination. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic 2021, 71, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J. Current issue in tourism: The evolution of travel medicine research: A new research agenda for tourism? Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryglova, K.; Vajcnerova, I.; Sacha, J.; Stojarova, S. The quality of competitive factor of the destination. J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yin, X.; Pengue, W.; Benetto, E.; Huisingh, D.; Schnitzer, H.; Wang, Y.; Casazza, M. Environmental accounting: In between raw data and information use for management practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1056–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adina, S.S.; Dars, A.; Memon, K.; Kazi, A.G. A Study of Factors Affecting Travel Decision Making of Tourists. J. Econ. Inf. 2020, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K.C.; Lin, H.H.; Lin, J.W.; Chen, I.S.; Hsu, C.H. Under the COVID-19 Environment, Will Tourism Decision Making, Environmental Risks, and Epidemic Prevention Attitudes Affect the People’s Firm Belief in Participating in Leisure Tourism Activities? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Every, D.; McLennan, J.; Reynolds, A.; Trigg, J. Australian householders’ psychological preparedness for potential natural hazard threats: An exploration of contributing factors. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 38, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Hasim, S.M. Factors and competitiveness of Malaysia as a tourist destination: A study of outbound Middle Eat Tourist. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khazai, B.; Mahdavian, F.; Platt, S. Tourism Recovery Scorecard (TOURS)—Benchmarking and monitoring progress on disaster recovery in tourism destinations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chiu, Y.-h.; Tian, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q. Safety or Travel: Which Is More Important? The Impact of Disaster Events on Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Firtko, A.; Edenborough, M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masser, B.M.; White, K.M.; Hamilton, K.; McKimmie, B.M. An examination of the predictors of blood donors’ intentions to donate during two phases of an avian influenza outbreak. Transfusion 2011, 51, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Liu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Duan, J.; Li, J. An overview of tourism risk perception. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 643–658. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11069-016-2208-1 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Poon, P.; Xie, L. Enhancing users’ well-being in virtual medical tourism communities: A configurational analysis of users’ interaction characteristics and social support. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuningtyas, D.; Ariwibowo, D.A. The strategic role of information communication technology in succeeding medical tourism. Enfermería Clínica 2020, 30, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Hu, X. The public needs more: The informational and emotional support of public communication amidst the Covid-19 in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 84, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of Social Media in Online Travel Information Search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleicher, F.; Petty, R.E. Expectations of reassurance influence the nature of fearstimulated attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 28, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolničar, S. Understanding barriers to leisure travel: Tourist fears as a marketing basis. J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Al-Ansi, A.; Lee, M.J.; Han, H. Impact of health risk perception on avoidance of international travel in the wake of a pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, A.S.; Mohammadi, Z.; Agarwal, M.; Kamble, Z.; Donough-Tan, G. Motivating or manipulating: The influence of health-protective behaviour and media engagement on post-COVID-19 travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2088–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Petrović, D.M.; Blešić, I.; Radovanović, M.; Syromjatnikowa, J. The Power of Fears in the Travel Decisions: COVID-19 vs. Lack of Money. J. Tour. Futures 2020, 9, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Gerritsen, R. What Do We Know about Social Media in Tourism? A Review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 10, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, J.M.; Porter, K.J.; Chen, Y.; Hedrick, V.E.; You, W.; Hickman, M.; Estabrooks, P.A. Predicting sugar-sweetened behaviours with theory of planned behaviour constructs: Outcome and process results from the SIP smart ER behavioural intervention. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Țuclea, C.E.; Vrânceanu, D.M.; Năstase, C.E. The Role of Social Media in Health Safety Evaluation of a Tourism Destination throughout the Travel Planning Process. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F.; Mitsopoulou, E.; Moustaka, E.; Kamariotou, M. User-Generated Content behavior and digital tourism services: A SEM-neural network model for information trust in social networking sites. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Maumbe, K.; Deng, J.; Selin, W.S. Resource-based destination competitiveness evaluation using a hybrid analytical hierarchy process (AHP): The case study of West Virginia. Tour. Manag. 2015, 15, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, A.E.; Hobbs, M.J.; Newby, J.M.; Williams, A.D.; Sunderland, M.; Andrews, G. The Worry Behaviors Inventory: Assessing the behavioral avoidance associated with generalized anxiety disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 203, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Kang, S.; Song, H. Applying protection motivation theory to understand international tourists’ behavioural intentions under the threat of air pollution: A case of Beijing, China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeh, J.K.; Au, N.; Law, R. Do We Believe in TripAdvisor?” Examining Credibility Perceptions and Online Travelers’ Attitude toward Using User-Generated Content. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Khan, F.; Amin, S.; Chelliah, S. Perceived risks, travel constraints, and destination perception: A study on sub-saharan African medical travellers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafi, A. The influence of social media on destination choice of Omani pleasure travelers. Int. J. Qual. Res. Serv. 2018, 3, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thananusak, T.; Zhu, R.; Punnakitikashem, P. Response of an Online Medical Tourism Facilitator Platform. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 204, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güneralp, B.; Güneralp, I.; Liu, Y. Changing global patterns of urban exposure to flood and drought hazards. Glob. Environ.Chang. 2015, 31, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blešić, I.; Ivkov, M.; Tepavčević, J.; Popov Raljić, J.; Petrović, M.; Gajić, T.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Aleksić, M.; et al. Risky Travel? Subjective vs. Objective Perceived Risks in Travel Behaviour—Influence of Hydro-Meteorological Hazards in South-Eastern Europe on Serbian Tourists. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, I.C.; Novani, S.; Suryana, L.A. Tourists’ Intentions During COVID-19: Push and Pull Factors in Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2022, 30, 699–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta Zanin, G.; Gentile, E.; Parisi, A.; Spasiano, D.A. Preliminary Evaluation of the Public Risk Perception Related to the COVID-19 Health Emergency in Italy. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, B.; Ahmed, B.; Vogt, J. Living with the Risks of Cyclone Disasters in the South-Western Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Environments 2017, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, A.; Mair, J.; Croy, G. Social media influence on tourists’ destination choice: Importance of context. Tour. Recreat. Resarch 2020, 45, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachinger, G.; Renn, O.; Begg, C.; Kuhlicke, C. The risk perception paradox—Implications for governance and communicationof natural hazards. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, D.B.; Zobov, A.M.; Degtereva, E.A. The nexus between tourism and regional real growth: Dynamic panel threshold testing. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic 2022, 72, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, J.; Lukić, T.; Besermenji, S.; Blešić, I. Creating a literary route through the city core: Tourism product testing. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic 2021, 71, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanovć, M.M.; Ðoković, F.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Kovačić, S.; Jošanov Vrgović, I.; Tretyakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A. Stereotypes and Prejudices as (Non) Attractors for Willingness to Revisit Tourist-Spatial Hotspots in Serbia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.; Taylor, E.C.; Cloonan, S.A.; Dailey, N.S. Psychological Resilience During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Sun, J.; Wei, D.; Qiu, J. Recover from the adversity: Functional connectivity basis of psychological resilience. Neuropsychologia 2019, 122, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Bonanno, G.A. Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, G.; Pfister, H.R. Tourism in the Face of Environmental Risks: Sunbathing under the Ozone Hole, and Strolling through Polluted Air. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 11, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, S.; Jovanović, T.; Miljković, Ð.; Lukić, T.; Marković, S.B.; Vasiljević, Ð.A.; Vujičić, M.D.; Ivkov, M. Are Serbian tourists worried? The effect of psychological factors on tourists’ behavior based on the perceived risk. Open Geosci. 2019, 11, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J.; Hinton, C.F.; Sinclair, L.B.; Silverman, B. Enhancing individual and community disaster preparedness: Individuals with disabilities and others with access and functional needs. Disabil Health J. 2018, 11, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turconi, L.; Faccini, F.; Marchese, A.; Paliaga, G.; Casazza, M.; Vojinovic, Z.; Luino, F. Implementation of Nature-Based Solutions for Hydro-Meteorological Risk Reduction in Small Mediterranean Catchments: The Case of Portofino Natural Regional Park, Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.; Mair, J.; Ritchie, B. Understanding the tourist’s response to natural disasters: The case of the 2011 Queensland foods. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 21, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.Y. An Investigation of Factors Influencing the Risk Perception and Revisit Willingness of Seniors. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2021, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.; Siegrist, M. Differences in Risk Perception between Hazards and between Individuals. In Psychological Perspectiveson Risk and Risk Analysis: Theory, Models, and Applications; Raue, M., Lerner, E., Streicher, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Poku, G.; Boakye, K.A.A. Insights into the safety and security expressions of visitors to the Kakum National Park: Implications for management. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Dai, S.; Xu, H. Predicting tourists’ health risk preventative behaviour and travelling satisfaction in Tibet: Combining the theory of planned behaviour and health belief model. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Jang, S.S. Why do customers switch? More satiated or less satisfied. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Duarte, P.; Henriques, C. Travelers’ use of social media: A clustering approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinoni, J.; Vogt, J.V.; Naumann, G.; Barbosa, P.; Dosio, A. Will drought events become more frequent and severe in Europe? Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 1718–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, F.; Tipu Sultan, M.; Badulescu, D.; Badulescu, A.; Borma, A.; Li, B. Sustainable destination marketing ecosystem through smartphone-based social media: The consumers’ acceptance perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.H.; Gretzel, U.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Trust in Travel-Related Consumer Generated Media. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2009; Höpken, W., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2009; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, A.; Pennington-Gray, L. The Role of Social Media in International Tourist’s Decision Making. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.T.; Sharmin, F.; Badulescu, A.; Stiubea, E.; Xue, K. Travelers’ Responsible Environmental Behavior towards Sustainable Coastal Tourism: An Empirical Investigation on Social Media User-Generated Content. Sustainability 2021, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaosiri, Y.N.; Fiol, L.J.C.; Tena, M.Á.M.; Artola, R.M.R.; García, J.S. User-Generated Content Sources in Social Media: A New Approach to Explore Tourist Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.; Martynyshyn, Y.; Khlystun, O.; Chukhrai, L.; Kliuchko, Y.; Savkiv, U. Optimisation of the Educational Environment Using Information Technologies. IJCSNS Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2021, 21, 80–83. Available online: https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO202121055697013.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Shah, S.M.; Liu, G.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Casazza, M.; Agostinho, F.; Lombardi, G.V.; Giannetti, B.F. Emergy-based Valuation of Agriculture Ecosystem Services and Dis-services. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 575, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Lee, B.C.; Byun, H.J. In the COVID-19 Era, When and Where Will You Travel Abroad? Prediction through Application of PPM Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotis, J.; Buhalis, D.; Rossides, N. Social Media Impact on Holiday Travel Planning: The Case of the Russian and the FSU Markets. Int. J. Online Mark. 2011, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, A. Online User-Generated Content for Travel Planning—Different for Different Kinds of Trips? Rev. Tour. Res. 2012, 10, 76–85. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20133261159 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Van Hoof, H. Social Media in Tourism and Hospitality: A Literature Review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Prayag, G.; Moital, M. Consumer Behaviour in Tourism: Concepts, Influences and Opportunities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 872–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. Tourist destination risk perception: The case of Israel. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2006, 14, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mehraliyev, F.; Liu, C.; Schuckert, M. The roles of social media in tourists’ choices of travel components. Tour. Stud. 2020, 20, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, A.C.; Shiau, W.L. Understanding Facebook to Instagram migration: A push-pull migration model perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 33, 272–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Amin, I.; Santos, C.; Antonio, J. Tourist’s motivations to travel: A theoretical perspective on the existing literature. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 24, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, H.; Roy, D.; Mia, R. Influence of Social Media on Tourists’ Destination Selection Decision. Sch. Bull. 2019, 5, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusby, C. Benefits and threats of travel and tourism in a globalized cultural context. World Leis. J. 2021, 63, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, T. An Analysis of the connotation of Tourist Destination Competitiveness and Its Conceptual Model: The Perspectives of Language, Logic and Epistemology. Tour. Sci. 2013, 3, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S.; Zhao, L.; Chen, A.; Huang, H. Understanding the antecedents of customer loyalty in the Chinese mobile service industry: A push–pull–mooring framework. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2014, 12, 551–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-97932-000 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Klenosky, D.B. The “pull” of tourism destinations: A means-end investigation. J. Travel Res. 2002, 40, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, C.K.; Klenosky, D.B. The influence of push and pull factors at Korean national parks. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phau, I.; Lee, S.; Quintal, V. An Investigation of Push and Pull Motivations of Visitors to Private Parks: The Case of Araluen Botanic Park. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A.; Alsawafi, A.M. Exploring Attitudes of Omani Students towards Vacations. Anatolia-Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 22, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Oom do Valle, P.; Moço, C. Modeling Motivations and Perceptions of Portuguese Tourists. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M.; Laguna, M.; Palacios, A. The Role of Motivation in Visitor Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence in Rural Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. A note on the multiplying factors for various χ2 approximations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1954, 16, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, P.; Walker, S.N. Theoretical and methodological differentiation of moderation and mediation. Nurs. Res. 1993, 42, 276–279. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8415040/ (accessed on 15 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.; Johnson, B. Media Amplification of Environmental Risks and Tourist Behavior. J. Tour. Stud. 2019, 40, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. Sensationalism and Alarmism: Media Narratives During Environmental Crises. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlberg, A.A.F.; Sjoberg, L. Risk perception and the media. J. Risk Res. 2000, 3, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S. An analysis of the social media practices for sustainable medical tourism destination marketing. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2017, 7, 222–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Push Factors | Pull Factors | Mooring Factors | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | m | λ | Items | m | λ | Items | m | λ | ||||||||||||||

| Escape from daily routine | 2.10 | 0.780 | Experience | 2.16 | 0.751 | Safer during environmental risks | 3.68 | 0.755 | ||||||||||||||

| Escape from the pressure of work | 2.93 | 0.684 | Events | 2.05 | 0.623 | Affordable destinations | 3.86 | 0.729 | ||||||||||||||

| Relax and rest | 2.24 | 0.718 | Special gastronomy | 2.47 | 0.635 | Less social risk | 3.04 | 0.757 | ||||||||||||||

| Recharge mental and physical health | 3.15 | 0.726 | CHSE | 4.28 | 0.684 | Absence of terrorism | 3.24 | 0.796 | ||||||||||||||

| Enjoy time with family and friends | 2.16 | 0.731 | Comfortable place | 2.11 | 0.805 | Safer to stay after the pandemic | 3.56 | 0.818 | ||||||||||||||

| Factor measurements | Factor measurements | Factor measurements | ||||||||||||||||||||

| m | α | CR | AVE | %Variance | M | α | CR | AVE | %Variance | m | α | CR | AVE | %Variance | ||||||||

| 2.51 | 0.772 | 0.874 | 0.684 | 46.226 | 2.62 | 0.761 | 0.890 | 0.633 | 11.768 | 3.47 | 0.810 | 0.940 | 0.762 | 5.666 | ||||||||

| Media Factors | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Items | m | λ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Exaggerate information about ER and increase fear among tourists | 3.88 | 0.871 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Presents real information after ER | 3.57 | 0.767 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Creates a sense of security after ER | 3.06 | 0.863 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Factor measurements | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| m | A | CR | AVE | %Variance | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.50 | 0.885 | 0.872 | 0.697 | 3.973 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gender | Frequency of Traveling to a MD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 47.7% | I have never traveled to a MD * | 22.1% |

| Female | 52.3% | I have traveled once a year | 49.3% |

| I have traveled several times a year | 28.6% | ||

| Education | Earning | ||

| High school | 24% | Low (≤500 Euros) | 1.8% |

| Faculty degree | 59% | Average (500–1.000 Euros) | 66.9% |

| MSc, PhD | 17% | High (>1.000 Euros) | 31.3% |

| Age | Country of residence N = 1.361 | ||

| 18–30 | 10% | Russian Federation | 935 |

| 31–55 | 63% | Republic of Serbia | 426 |

| >56 | 37% | ||

| Influences | β | t | p | Confirmation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | <-- | Push factors | −0.02 | −1.075 | 0.282 | H1a |  |

| MD | <-- | Pull factors | 0.51 | 3.338 | *** | H1b |  |

| MD | <-- | Mooring factors | 0.00 | 0.083 | 0.934 | H1c |  |

| MD | <-- | Moderator | 0.938 | 52.143 | *** | H2 |  |

| MD | <-- | Moderation-pull factors | −0.072 | −4.609 | *** | H3a |  |

| MD | <-- | Moderation-push factors | 0.055 | 3.333 | *** | H3b |  |

| MD | <-- | Moderation-mooring factors | 0.056 | 0.394 | 0.04 | H3c |  |

| X2 | Df | p | Deviance | McFadden | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21.863 | 134 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.325 | |

| Parameter Estimates for choosing destinations | 95% Confidence Interval for Exp(B) | ||||

| β | p | Exp(B) | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| MD | −0.111 | 0.039 | 0.895 | 0.806 | 0.994 |

| RD | 0.117 | 0.054 | 0.895 | 1.011 | 1.250 |

| Classification statistics of determined group memberships predicted by the model | |||||

| MD | RD | UD | |||

| 70.8% | 46.5% | 5.3% | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gajić, T.; Minasyan, L.A.; Petrović, M.D.; Bakhtin, V.A.; Kaneeva, A.V.; Wiegel, N.L. Travelers’ (in)Resilience to Environmental Risks Emphasized in the Media and Their Redirecting to Medical Destinations: Enhancing Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115297

Gajić T, Minasyan LA, Petrović MD, Bakhtin VA, Kaneeva AV, Wiegel NL. Travelers’ (in)Resilience to Environmental Risks Emphasized in the Media and Their Redirecting to Medical Destinations: Enhancing Sustainability. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115297

Chicago/Turabian StyleGajić, Tamara, Larisa A. Minasyan, Marko D. Petrović, Victor A. Bakhtin, Anna V. Kaneeva, and Narine L. Wiegel. 2023. "Travelers’ (in)Resilience to Environmental Risks Emphasized in the Media and Their Redirecting to Medical Destinations: Enhancing Sustainability" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115297

APA StyleGajić, T., Minasyan, L. A., Petrović, M. D., Bakhtin, V. A., Kaneeva, A. V., & Wiegel, N. L. (2023). Travelers’ (in)Resilience to Environmental Risks Emphasized in the Media and Their Redirecting to Medical Destinations: Enhancing Sustainability. Sustainability, 15(21), 15297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115297