The Application of a Process Approach to the National Governance System for Sustainable Development: A Case Study in Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Methodology used

- Novelty of thepaper

2. A Literature Review on the National Framework of Governance for Sustainable Development

- The publication of the “Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)”, entitled “Governance as an SDG Accelerator“ [9] illustrates the main ingredients of a whole-of-government approach to strategic visioning, priority setting, and implementation of the SDGs. In the authors’ view, SD governance involves the design, implementation, and effective delivery of public policies, and in this sense, three processes are carried out: (1) elaboration of strategies; (2) planning operational actions; and (3) monitoring and evaluation. The key role of robust coordination mechanisms is emphasized in ensuring policy coherence and successfully addressing the multi-dimensional policy challenges that characterize the SDGs. The authors also stress the need to develop an appropriate structure with a strong coordination body at a high level and refer distinctly to some governance processes, namely strategic planning and priority-setting; public procurement; and human resources, skills, and digital tools to support the SDGs implementation.

- The study of Niestroy et al. [10], carried out under the auspices of the European Parliament, examines the governance frameworks used to implement the SDGs in the “European Union (EU)” member states. The analysis model includes seven elements of SD governance, namely, (1) commitment and strategy; (2) leadership and horizontal coordination; (3) stakeholder participation; (4) monitoring and review; (5) knowledge and tools; (6) institutions for the long-term; and (7) activities of Parliaments for Agenda 2030.

- The book by Monkelbaan [11] is a complex study that includes theoretical considerations on essential elements for a global analysis of SD governance and several case studies. A distinct chapter refers to the key competences of governance for SDGs, which are structured in three pillars: (1) power (leadership; networking and stakeholder management; empowerment); (2) knowledge (knowledge cooperation; adaptiveness and resilience; reflexivity); and (3) norms and values (equity; creating horizontal and vertical trust; inclusiveness and pluralism).

- Comments on the national governance framework for SD are also made by Morita, Okitasari, and Masuda [12], which focus on the evaluation of national and local governance systems for achieving SDGs. Starting from the existing publications, the authors remark that there are not effective tools for analyzing governance systems that aim to implement SDGs. The solution adopted by the authors is the matrix tool of the “Governance System Analysis” proposed by Dale, Vella, and Potts [13], which includes five key structural components: (1) vision and objective settings; (2) research and assessment; (3) strategy development; (4) strategy implementation; and (5) monitoring, evaluation, and review. Furthermore, each component includes three key functions, namely, decision-making capacity, connectivity, and knowledge use. Following the comparative analysis of the governance systems for SDGs in Japan and Indonesia based on this model, the authors conclude the need to improve it in terms of the tools and indicators used to evaluate the real effects of governance.

- Villeneuve and Lanmafankpotin [14] propose a guiding model for the national SD governance evaluation, which was included in the UN Sustainability Acceleration Toolkit [15]. The main components of this model are as follows: (1) national institutional framework; (2) strategic coordination; (3) interaction with sub- and supra-national levels; (4) accommodating stakeholders; (5) monitoring and ongoing evaluation; (6) capacity-building for authorities and stakeholders. Each of these components includes several elements/criteria. As an example, the “National institutional framework” component is analyzed based on ten criteria: vision; principles; legal document; policy, strategy, or equivalent plans; horizontal integration; budgeting; national resources; greenhouse gas reduction target; development and implementation tools; government departments and agencies that help to implement the SD strategy.

- One such study was elaborated by Nestroy [16], which focused on the tools for SD integration. The author remarks that there are universal tools adopted by the UN that support the process of integrating SDGs into national governance, but they must be adapted to the context of each country, taking into account specific national realities and capacities. The expression “meta-governance approach” is used in connection with this contingent transformation. The paper focuses on the steps of governance transformations that need to be made at national level and refers to three major components of the SD governance system: (1) strategies; (2) institutional (organizational) arrangements; and (3) processes, including supporting tools. Particular attention is paid to national culture, and some interpretations are presented regarding the relationship between SD integration approaches/tools and the cultural context and the governance environment.

- A similar approach was taken by Meuleman and Niestroy [17] in their work, which focused on meta-governance combined with key governance principles as a mechanism to support the analysis, design, and management of SDG governance framework. The authors stress that the implementation of SDGs requires systemic thinking, comprehensive approaches (taking into account all relevant aspects), and, in addition, a holistic view.

- O-Connor et al. [18] examine the transformations in several OECD-developed countries aimed at implementing the 2030 Agenda. The case studies refer to some components of the governance for SD, namely (1) governmental structures and coordination; (2) SD strategy and objectives statement; (3) policy elaboration and coherence; (4) vertical communication with the sub-national levels; and (5) evaluation process and review of progress.

- In their paper, Fyson, Lindberg, and Morales [19] underline that implementing the 2030 Agenda represents a complex governance challenge and needs “to boost the capacity of governments to plan, to coordinate, to act, and to serve as a catalyst in support of SDGs implementation”. The authors refer to some enablers for accelerating progress on the SDGs, namely (1) vision and leadership (expressed at the highest levels and backed by strategies, policies, legislation, action plans, instructions and incentive, which are essential to pursue SDGs in a coherent manner); (2) coordinated actions (dedicated coordination mechanisms and tools, and collaborative partnership with all stakeholders and sub-national levels of governance); (3) impact (evaluation processes for assessing the progress toward the SDGs and the impact of the SD policies); (4) human resource (the capacity and leadership skills of civil servants to understand the complex relationships between the SDGs, and their ability to turn governance principles into actions).

- Finally, it must be said that two of the SDGs (numbers 16 and 17) from the 2030 Agenda [7] focus on governance systems, but the aspects they refer to do not provide a complete picture of NGS-SD. The SDG16 specific targets are associated with improving the decision-making process, efficient, responsible, and transparent institutions, and the professionalization of institutions. And SDG17 refers to policy coherence in SD, developing an action plan, and updating specific national indicators. Several official documents—guidelines and tools developed at the UN level and by other global and regional bodies—support the implementation of these SDGs. There are also studies that try to identify the influencing factors associated with the SDG17 achievement in relation with the UN’s seven categories of implementation means: resource mobilization, technology, capacity building, trade, policy and institutional coherence, multi-stakeholder partnerships, data, monitoring, and accountability [20,21]. These studies, as well as the official documents related to SDG 16 and 17, are undoubtedly useful, but they focus on analytical frameworks for the development of specific governance mechanisms and do not cover the entire governance system.

3. Process Architecture of the National Governance System for Sustainable Development

- (1)

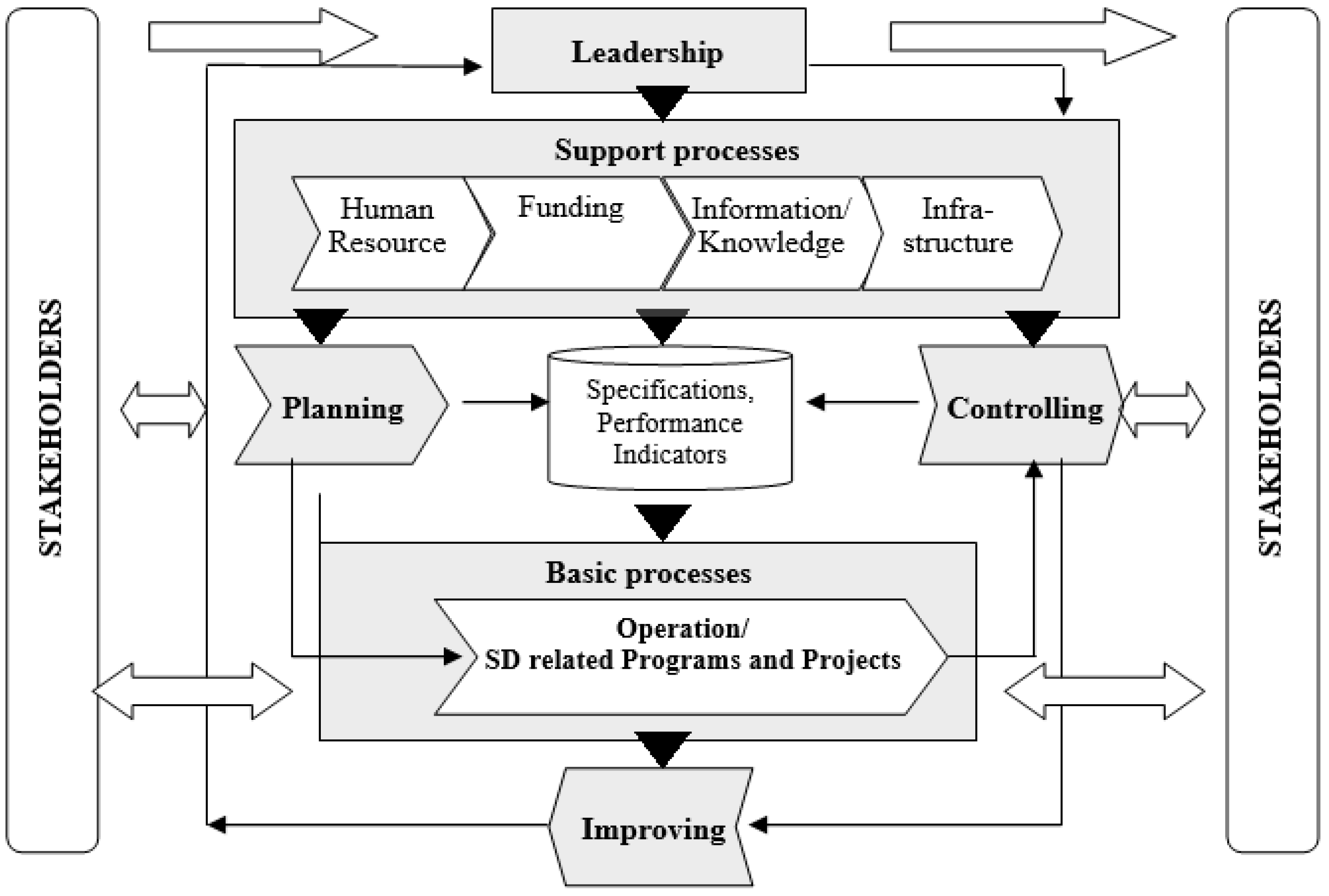

- The “Leadership” process plays a key role in the creation of the overall action framework for SD governance, performing several functions:, including defining principles and policies on SD; developing national strategy, objectives, and axes of action; establishing responsibilities/structures; communication and developing the SD culture; NGS-SD management; and SD regulation management. Establishing responsibilities refers to the creation of specific SD bodies and functions at the national level of governance. Developing coherent policies and national strategies represents activities/sub-processes that aim to ensure the establishment of the long-term SD direction and objectives, as well as the behavioral changes necessary for the SD to be integrated into daily life at the national level. In this regard, communication on SD values and strategy is a very important process, contributing to the development of SD culture.

- (2)

- The planning/control/improvement processes define the cycle of management actions aimed at developing national SD plans, controlling activities and results, and improving performance. The major issues in SD planning are the establishment of national SD indicators and the prioritization of actions, taking into account their impact and existing resources. The control aims to measure and evaluate the results and progress in the field of SD from the perspective of the SDGs and the evaluation of the governance system. The assessment is performed at the government level, but the regular reporting of SD actions resulting in higher levels of multi-level governance is also included in this process. According to Niestroy et al. [10] (p. 28), a robust monitoring and review framework is crucial for an effective and operational strategy. The improvement is based on the results provided by the control and implies the elimination of deficiencies in terms of the SDGs and the way of governance, as well as the transition to new levels of performance through innovation. According to Meuleman [8] (p. 7), “SD is a laboratory for governance innovation (how will the goals be achieved?) but also for policy innovation (which concrete goals need to be set in a specific situation?)”.

- (3)

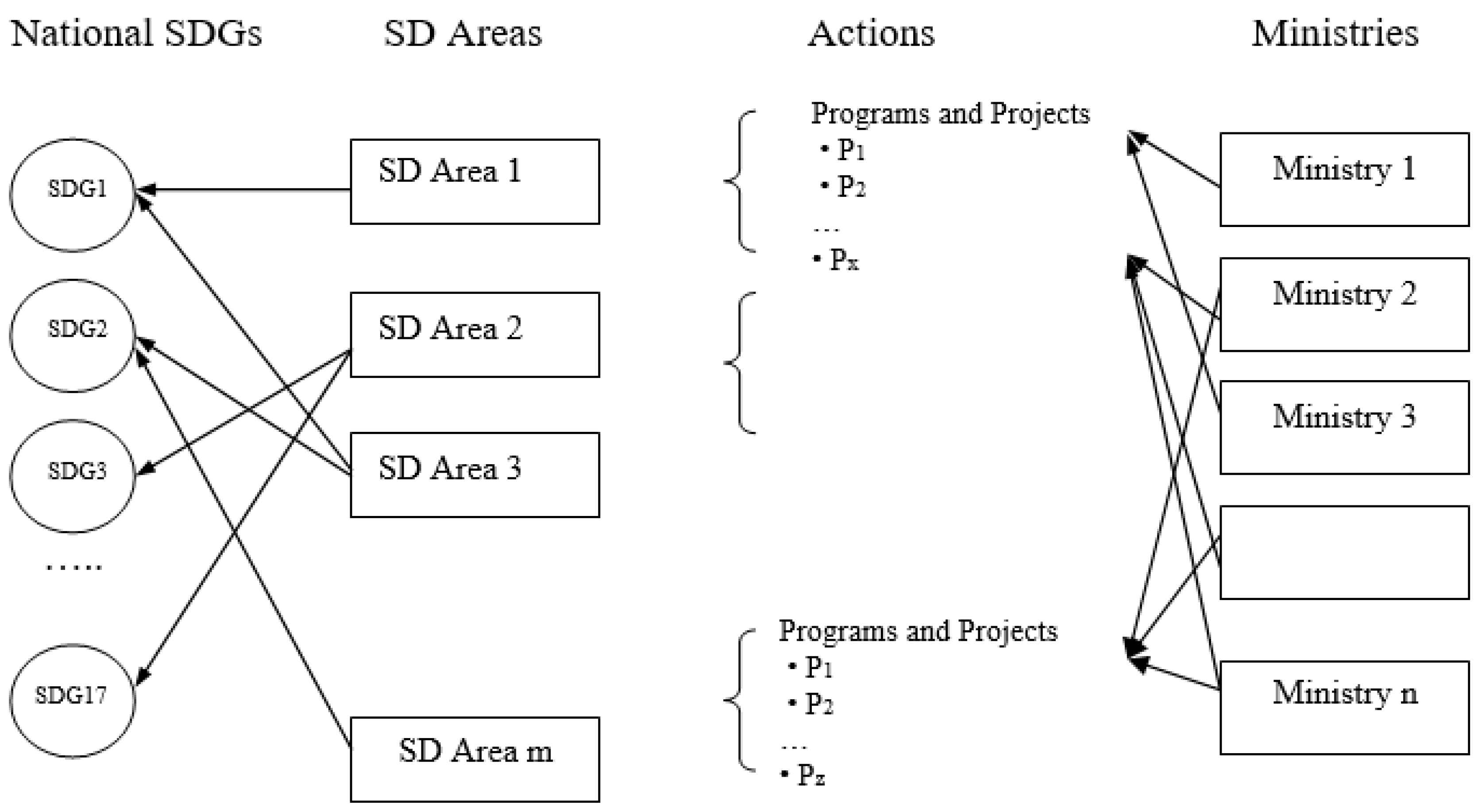

- The basic processes (“operation”) define the actions with direct effects on the overall results. In the case of NGS-SD, the operation process takes the form of development programs and projects with specific SD objectives, coordinated by the line ministries or inter-ministries. The key areas of action are defined by the national policies, strategies, and plans for SD, which are based on horizontal integration, but they are also harmonized with those adopted at higher levels of SD governance. Currently, the reference points are the 2030 Agenda and the 17 SDGs, with which thematic areas are associated.

- (4)

- The support processes refer to providing the necessary resources for SD. The processes in this category are the same as those of the UN governance system for SD, namely “Human Resource”, “Financing”, and “Information Management”. The process of “Infrastructure” could be added to better control the way that the infrastructure for national SD governance is developed. Particular aspects regarding the accomplishment of these processes are presented in the case study performed in Romania.

4. Case Study in Romania

- (1)

- Leadership

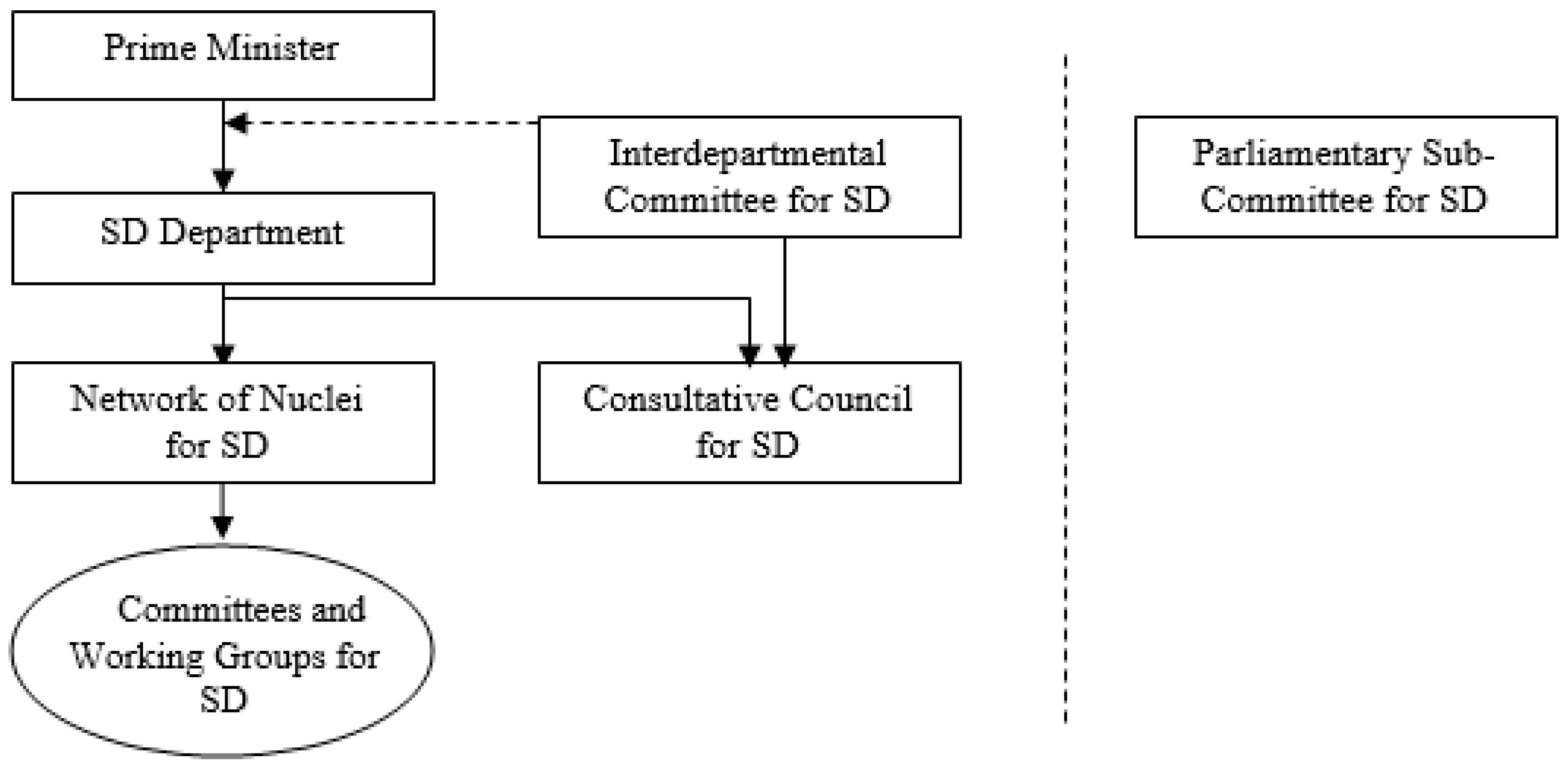

- The development of an adequate national structure for implementing SD in Romania in the context of the 2030 Agenda was one of the priority actions of the government. Currently, the central SD structure includes several ministerial entities (Figure 3) and other independent organizations.

- Elaborating strategies for SD is a key process in the effective governance of SD at all levels. The “National strategy for SD of Romania (NSSDR)” 2030 was adopted by the Romanian Government in 2018 [32]. The NSSDR has three parts, which refer to the following: SD-related vision and engagement; the evaluation of the first decade of implementation of the SD strategy approved by the Romanian government in 2008 and the new strategic objectives and targets for the 17 SDGs, in line with the 2030 Agenda and relevant EU provisions; the strategy implementation and monitoring.

- The “Communication” process refers to government actions to promote SD values, policies, and strategies and other SD issues at the country level.

- The process of “NGS-SD Management” must be coordinated by the Prime Minister and the SD Department. Aspects related to the SD governance system are integrated into SDG16 and SDG17 of NSSDR, but they are also distinctly approached in the plan of action for NSSDR implementation [38]. A picture of the NGS-SD global architecture does not exist, but there are management tools related to different components of the governance for SD, which are discussed in the analysis of processes to which they refer.

- Regarding the process of managing SD regulations, it is worth noting that the SD Department made the first analysis on SD legislation in Romania from the perspective of NSSDR implementation within the project “Sustainable Romania” [39] (pp. 57–79). The project pursued the creation of databases with the relevant SD normative acts and their mapping on the 17 SDGs of NSSDR. Some deficiencies were highlighted, e.g., redundant regulations, uneven coverage of the SDGs, etc. What is important are the proposals formulated by the authors, namely the creation of a unique database with normative acts relevant to the NSSDR; the development of a distinct module for the management of documents of strategic importance; inclusion in all legislative documents of an explicit section describing the link and relevance to the NSSDR. To these aspects related to SD regulations, there are added the general requirements regarding the quality of the legislative process, which are associated with QoG.

- Processes on “policy coherence”, “stakeholders engagement”, and “partnership management”.

- (2)

- Management cycle of the planning/control/improvement processes.

- Planning refers to the actions required to achieve the 17 SDGs, and it consists of establishing the portfolio of SD programs and projects, taking into account the alignment of the national budget with SD objectives and national SD indicators. Planning, as well as the monitoring of results and the assessment of progress in SD areas, is based on a set of national indicators of SD. In 2022, in Romania, a new set of SD indicators was launched, including 291 indicators (99 main and 192 additional indicators), harmonized with those established at the UN and EU levels. The new national SD indicator set was integrated into the online open data platform “Aggregator Sustainable Romania” [48], which was launched in November 2022. The platform automatically collects the national and European official statistical data from the databases of the National Institute of Statistics and the “Statistical Office of the EU (Eurostat)”.

- The “Control” process has multiple materializations, including the monitoring and evaluation actions related to the following: achieving the SDGs; measurement of the national SD indicators and evaluation of progress; assessment of the governance system for SD, etc. The Prime Minister and SD Department are responsible for this process.

- The “Improvement” process refers to the systematic actions aiming to improve the results concerning the SDGs as well as the SD governance processes and tools. The EU mechanisms, namely the European Semester and Country Recommendations, are important in this regard. The tool that is currently used in the EU member states is the NPRR, introduced after the COVID-19 crisis, which comprises reforms and investments aiming to assure an inclusive and sustainable recovery. The NPRR represents a good opportunity for Romania’s SD. The general objective of the NPRR [54] of Romania is the development of Romania by carrying out essential programs and projects that support resilience, preparedness for crisis situations, adaptability, and growth potential through major reforms and key investments supported by European Funds. Romania’s NPRR is structured on fifteen components covering the next six pillars: green transition; digital transformation; smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth; social and territorial cohesion; health; as well as economic, social, and institutional resilience; and policies for the new generation. The implementation of the proposed projects will generate improvements in most SD objectives, given the specificity of the European recovery and resilience mechanism through which they are funded and which has a strong component of greening, climate change, and digitalization.

- (3)

- Operation processes

- (4)

- Support processes

- The “Human Resource (HR)” process refers to the specific actions of HR management with effects on performance in SD [6]. The most important component of this process is the educational one.

- Funding process

- SD information/knowledge process

- Infrastructure/computerization process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meadowcroft, J. Who is in Charge here? Governance for Sustainable Development in a Complex World. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, U.; Lange, L.; Berger, B. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Governance for SD Principles, Approaches and Examples in Europe; ESDN Quarterly Report No 38; European Sustainable Development Network: Vienna, Austria, 2015; Available online: https://www.esdn.eu/fileadmin/ESDN_Reports/2015-October-The_2030_Agenda_for_Sustainable_Development.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future (Brundtland Report); Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Available online: https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/media/publications/sustainable-development/brundtland-report.html (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Mulholland, E.; Berger, G. Multi-Level Governance and Vertical Policy Integration: Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at All Levels of Government; ESDN Quarterly Report 43; ESDN Office: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allain-Dupré, D. The Multi-level Governance Imperative. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2020, 22, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Mandru, L. A Model for Process Approach in the Governance System for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Meulement, L. Metagovernance for Sustainability. A Framework for Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals; Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Governance as an SDG Accelerator. Country Experiences and Tools; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirth, E.H.E.; Zondervan, R. Europe’s Approach to Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals: Good Practices and the Way Forward; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Monkelbaan, J. Governance for the Sustainable Development Goals. Exploring an Integrative Framework of Theories, Tools, and Competencies; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019; Available online: http://www.ru.ac.bd/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2019/03/408_09_00_Monkelbaan-Governance-for-the-Sustainable-Development-Goals-2019.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Morita, K.; Okitasari, M.; Masuda, H. Analysis of National and Local Governance Systems to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals: Case Studies of Japan and Indonesia. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Potts, R. Governance Systems Analysis: A Framework for Reforming Governance Systems. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2013, 3, 162–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Villeneuve, C.; Lanmafankpotin, G. The Governance of Sustainable Development Governance. Records User’s Guide; Université du Québec à Chicoutimi: Chicoutimi, QC, Canada, 2017; Available online: http://ecoconseil.uqac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Governance-Records-User%E2%80%99s-Guide_17juil17_VA.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Group. United Nations Sustainability Acceleration Toolkit. Available online: https://sdgintegration.undp.org/sdg-acceleration-toolkit#:~:text=The%20SDG%20Acceleration%20Toolkit%20is,identifying%20risks%20and%20building%20resilience (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Niestroy, I. Governance Approaches and Tools for Sustainable Development Integration: Good Practice (What Has Worked Where and Why) at National Level. In Proceedings of the UN DESA/UNEP Technical Capacity Building Workshop Sustainable Development Integration Tools, Geneva, Switzerland, 14–15 October 2015. Available online: https://www.ps4sd.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2015-SDIT_gov-context_Niestroy_NOV2015_final.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Meuleman, L.; Niestroy, I. Common but Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernance Approach to Make the SDGs Work. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12295–12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.; Mackie, J.; Van Esveld, D.; Kim, H.; Scholz, I.; Weitz, N. Universality, Integration, and Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development: Early SDG Implementation in Selected OECD Countries; Working Paper; World Resource Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.wri.org/publication/universality_integration_and_policy_coherence (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Fyson, S.; Lindberg, C.; Morales, E.S. Governance for the SDGs—How Can We Accelerate Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals? Dubai Policy Review. Available online: https://dubaipolicyreview.ae/governance-for-the-sdgs-how-can-we-accelerate-achieving-the-sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Bowen, K.J.; Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Koch, F.; Patterson, J.; Häyhä, T.; Vogt, J.; Barbi, F. Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: Towards Addressing Three Key Governance Challenges—Collective Action, Trade-Offs, and Accountability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford-Smith, M.; Griggs, D.; Gaffney, O.; Ullah, F.; Reyers, B.; Kanie, N.; Stigson, B.; Shrivastava, P.; Leach, M.; O’Connell, D. Integration: The Key to Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, L.M.; Newig, J. Governance for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How Important Are Participation, Policy Coherence, Reflexivity, Adaptation and Democratic Institutions? Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9000; Quality Management Systems—Fundamentals and Vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Council of the European Union. A Sustainable European Future: The EU Response to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—Council Conclusions (20 June 2017); Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/23989/st10370-en17.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- OECD. Romania: OECD Scan of Institutional Mechanisms to Deliver on the SDGs; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. Available online: https://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Romania-Institutional-Scan_final.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Government of Romania. Decision no. 313 of 11 May 2017 Regarding the Establishment, Organization and Operation of the Department for Sustainable Development; Official Monitor no. 356 of 15 May 2017; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2017.

- Government of Romania. Decision no. 272/2019 Regarding the Establishment of the Interdepartmental Committee for Sustainable Development; Official Monitor no. 363 of 10 May 2019; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2019.

- Government of Romania. Decision no. 114 of 4 February 2020 Regarding the Establishment of the Consultative Council for Sustainable Development; Official Monitor no. 100 of 11 February 2020; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2020.

- Consultative Council for Sustainable Development. The Sustainable Development of Romania in a European Context: From Vision to Action; UEFISCDI Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2023. Available online: http://romania-durabila.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Publicatia-CCDD-04.04.2023_electronic.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Department of Sustainable Development. Available online: https://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/cautare/rapoarte (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Embassy of Sustainability in Romania. Available online: www.ambasadasustenabilitatii.ro (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Government of Romania. Decision No. 877 of November, 2018 Regarding the Adoption of the National Strategy for Sustainable Development of Romania; Official Monitor no. 985 of 21 November 2018; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2018.

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. Communication from the Commission, COM(2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640&qid=1687843330460 (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Lafortune, G. (Coordinator); Europe Sustainable Development Report 2021: Transforming the European Union to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals; Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) Europe: Paris, France; Institute for a European Environmental Policy (IEEP): Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2021/Europe+Sustainable+Development+Report+2021.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Transformations for the Joint Implementation of Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development and the European Green Deal. A Green and Digital, Job-Based and Inclusive Recovery from the COVID-19 Pandemic; UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://irp-cdn.multiscreensite.com/be6d1d56/files/uploaded/SDSN_EGD%20Mapping%20Study_2021_final.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Charveriat, C.; Bodin, E. Delivering the Green Deal: The Role of a Reformed Semester within a New Sustainable Growth Strategy for the European Union; The Institute for European Environmental Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Romania. Report of the Government of Romania on the Implementation of Sustainable Development Objectives 2017–2021; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2022. Available online: https://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/files/public/14745850/ddd_raport_parlament_2021.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Government of Romania. Decision no. 754 of 8 June 2022 regarding the National Plan of Action for the Implementation of National Strategy for Sustainable Development of Romania 2030; Official Monitor no. 606 bis of 21 June 2022; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Sustainable Development. Evaluation Report of Policies, Plans and Sectoral Action Strategies in Relation to the Objectives of the National Strategy for the Sustainable Development of Romania 2030. Report within the Project, Sustainable Romania, Financed from the Operational Program Administrative Capacity. 2021. Available online: http://agregator.romania-durabila.gov.ro/doc/raport/Raport-de-evaluare-politici.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- OECD. Recommendation of the Council on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development; OECD/LEGAL/0381; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/pcsd/recommendation-on-policy-coherence-for-sustainable-development-eng.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- OECD. Taking Stock of Progress in Enhancing PCSD: Opportunities and Challenges in Implementing Romania’s National Action Plan for the National Strategy for Sustainable Development of Romania 2030; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. Available online: https://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/taking-stock-of-progress-in-enhancing-policy-coherence-for-sustainable-development-in-romania-opportunities-and-challenges-in-nap-implementation-11893430 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- OECD. Romania: Institutional Scan to Enhance Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/pcsd/romania-institutional-scan-key-findings.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Directorate for Public Governance. SDG Budgeting in Romania. Linking Policy Planning and Budgeting to Support the Implementation of the SDGs; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/oecd-review-of-sdg-budgeting-in-romania.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Ministry on Environment. Romania’s Voluntary National Review 2018; Ministry on Environment: Bucharest, Romania, 2019; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/19952Voluntary_National_Review_ROMANIA_with_Cover.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- United Nations & The Partnering Initiative. The SDG Partnership Guidebook. A Practical Guide to Building High Impact Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for the SDGs; Partnership Accelerator 2030 Agenda for, SD; The Partnering Initiative: Oxford, UK; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Sustainable Development. Activity Report, 2022; Department for Sustainable Development: Bucharest, Romania, 2022. Available online: https://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/raport-de-activitate-departamentul-pentru-dezvoltare-durabila-2022-14003476 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- General Secretariat of Government (Coordinator). Sustainable Romania: Development of the Strategic and Institutional Framework for the Implementation of the National Strategy for Sustainable Development of Romania 2030. General Secretariat of Government, 2019. Project Co-Financed from the European Social Fund through the Administrative Capacity Operational Program 2014–2020. Available online: http://romania-durabila.gov.ro/proiect/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Aggregator Sustainable Romania. Available online: http://romania-durabila.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/INDD_tinte2030_14febr2022.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Government of Romania. Decision no.427/2022 for the Approval of the Methodology for the Elaboration, Monitoring, Reporting and Revision of Institutional Strategic Plans; Official Monitor, Part I, no. 301 of 29 March 2022; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Romania. Voluntary National Review Romania 2023, Implementing the 17 SDGs, Report to the UN High-Level Political Forum for Sustainable Development, New York, 2023; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2023; Available online: https://hlpf.un.org/sites/default/files/vnrs/2023/VNR%202023%20Romania%20Report.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- United Nations. Romania Environmental Performance Reviews, Third Review—Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/ECE.CEP_.NONE_.20211.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Eurostat. Sustainable Development in the European Union—Monitoring Report on Progress towards the SDGs in the European Union Context. 2023 Edition; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/15234730/16817772/KS-04-23-184-EN-N.pdf/845a1782-998d-a767-b097-f22ebe93d422?version=1.0&t=1684844648985 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- European Sustainable Development Network. Available online: https://www.esdn.eu/country-profiles/review (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Ministry of Investments and European Projects. National Plan for Recovery and Resilience of Romania. Government of Romania; Ministry of Investments and European Projects: Bucharest, Romania, 2021. Available online: https://mfe.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/facada6fdd5c00de72eecd8ab49da550.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Ministry of Investments and European Projects. Available online: https://mfe.gov.ro/category/anunturi-pnrr/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Government of Romania. Emergency Ordinance Regarding the Establishment of Simplification and Digitization Measures for the Management of European Funds Related to the Cohesion Policy 2021–2027; Official Monitor of Romania, Part I, No. 319/13.IV.2023; Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of Europe. Regulation (EU) 2021/1.060 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2021. Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, L 231, 159–706. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32021R1060 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Government of Romania. Available online: https://data.gov.ro/organization/mfe (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development. A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Council of Europe. Council Recommendations of 16 June 2022 on Learning for the Green Transition and Sustainable Development (2022/C 243/01). Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, C 243, 1–9. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022H0627(01) (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- National Qualifications Authority. Decision no. 49/2021, Occupational Standard Sustainable Development Expert. Available online: http://romania-durabila.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/SO_expertdezvoltaredurabila-1.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- European Commission. Reflection Document: Towards a Sustainable Europe until 2030, COM(2019) 22 from January, 30, 2019; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2019-02/rp_sustainable_europe_ro_v2_web.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Ministry of Investments and European Projects. Sustainable Development Program. Available online: https://oportunitati-ue.gov.ro/program/programul-dezvoltare-durabila/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). Sustainable Finance Roadmap 2022–2024; ESMA: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma30-379-1051_sustainable_finance_roadmap.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Department for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/# (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- European Parliament; European Council. Decision (EU) 2022/2481 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022, Establishing the Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030. Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, L 323, 4–26. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022D2481&qid=1688231911971 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/en/ict4d/Go (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- European Commission. Digital Economy and Society Index 2022. Report/Study|Publication 28 July 2022. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2022 (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Authority for the Digitization of Romania. Available online: https://www.adr.gov.ro/ (accessed on 3 July 2023).

| Process | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership |

|

|

| Planning, Control, and Improvement |

|

|

| Operation |

|

|

| Support |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popescu, M.; Mandru, L. The Application of a Process Approach to the National Governance System for Sustainable Development: A Case Study in Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14885. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014885

Popescu M, Mandru L. The Application of a Process Approach to the National Governance System for Sustainable Development: A Case Study in Romania. Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14885. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014885

Chicago/Turabian StylePopescu, Maria, and Lidia Mandru. 2023. "The Application of a Process Approach to the National Governance System for Sustainable Development: A Case Study in Romania" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14885. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014885

APA StylePopescu, M., & Mandru, L. (2023). The Application of a Process Approach to the National Governance System for Sustainable Development: A Case Study in Romania. Sustainability, 15(20), 14885. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014885