Abstract

Empowering women is essential for poverty alleviation and open involvement of woman entrepreneurs in line for entrepreneurship development. Nonetheless, several woman-led enterprises and woman entrepreneurs have scarce opportunities to revitalize beyond the dearth of financial services to realize financial freedom. This article’s approach hinges on a bibliometric analysis to survey recent developments and trends in microfinancing woman-owned enterprises and how this field is expected to transform to recent financial technological progress over successive years. We review existing evidence from 402 published articles indexed in the Scopus database from January 2003 to March 2023 to explain the current research development and interrelated prospects for enhancing studies on microfinance for woman entrepreneurship. The results vividly indicate that access to a stream of microfinancing credit is fundamental to the prosperity of urban woman-led enterprises across all countries. Despite this, woman entrepreneurs still encounter several obstacles when starting new businesses or expanding existing ones. With a growing demand for substantial sums of external financing to transition to sustainable business practices, their contribution to sustainable development is most often unreachable. Thus, any financing strategies focused on allowing access to microfinance credit by woman entrepreneurs are necessary to enable this sector to receive the benefits of economic freedom. This study offers good insights for current and potential entrepreneurs to bridge the financing gaps in emerging economies as a strategy for strengthening the capability of woman entrepreneurs to pursue economic opportunities that can inspire sustainable business enterprises and contribute to sustainable development. Finally, the study provides a foundation for future research in the domain of entrepreneurial financing for MSMEs.

1. Introduction

In recent years, low-income nations have progressively gained interest in microfinance services as an antecedent for job creation and the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) [1,2]. The narrative among policymakers about women’s entrepreneurship is slowly shifting from merely focusing on the establishment of several start-ups to supporting women who are well positioned to lead growth-oriented enterprises. Research indicates that woman entrepreneurs can be agents of change and deliver innovative solutions to achieving sustainable development; however, they face multiple barriers to growing their businesses compared to their male counterparts [3]. Several studies state that woman-led businesses have the potential to grow with the right funding coupled with higher sales growth, profitability, and increasing investment returns [4,5]. Extending microfinance credit to woman entrepreneurs, especially through microfinance financial institutions (MFIs), is indispensable in a bid to realize financial freedom amongst women and the community at large [4,5,6,7]. According to [8], women constitute an estimated 80% of consumer purchasing choices, suggesting that woman-owned enterprises habitually produce improved products. Consequently, the number of borrowers is rising at 5.6% annually, with a growing loan portfolio of 15.6% annually. Notwithstanding increasing efforts from MFIs to expand financial inclusion, over 1.7 billion adults in developing countries are deprived of access to the traditional financial system [7,8]. Thus, the real effect of microfinance services on fostering the development of SMEs is frequently questioned [9].

In a similar manner, although the percentage of female entrepreneurs and woman-led enterprises is gradually increasing in the international corporate boardroom, the role of microfinance instruments in enhancing the performance and sustainable growth of this industry, especially in African countries, lacks extensive deliberations. Many traditional financial institutions are often hesitant to support woman-owned enterprises because they are perceived as risky ventures that fall short of good financial sense and business acumen. Furthermore, several woman-led enterprises and woman entrepreneurs have scarce opportunities to recover from dire financial circumstances to realize financial freedom [10,11]. SMEs in Africa account for 90% of the private sector and provide nearly 80% of jobs across the continent. On the contrary, woman-owned SMEs account for only 33.3% of all businesses in the global formal economy [12], yet they are integral to inspiring employment opportunities, improving the community livelihood of the productive poor, and achieving overall economic progress.

Thus, promising sustainable access to a series of microfinance credits to woman-led enterprises is crucial for fostering women’s economic freedom, the prosperity of community well-being, and poverty alleviation across developing countries [4,7], particularly towards achieving sustainable development goals (SGDs). Recent studies expose that women’s economic participation has been identified as a significant factor in this outcome [4]. Similarly, the Boston Consulting Group shares the view that the vast socio-economic contribution made by woman entrepreneurs across the world to the global economy yields higher returns and tends to be more financially fruitful than the contribution by their male counterparts, making woman entrepreneurs a safe bet for investors and funders. A survey [7] reveals that Africa is the only continent where more women choose to become entrepreneurs. To reinforce the later statement, [13] described that sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the higher rate of entrepreneurial activity among women than male entrepreneurs. However, the question that has been left unanswered is: “Why do female entrepreneurial firms receive inadequate equity funding compared to their male counterparts?”

Notwithstanding the several empirical studies on the importance of access to finance for firm growth [11,14,15,16,17,18], not many have attempted to explore the impact of microfinance credit on the performance and growth of woman-owned enterprises [18,19], and amongst these few, not a single study paints a good picture of the situation faced by woman-owned enterprises in East African countries. Although SMEs encounter a series of barriers to their survival and inclusive growth, prior studies have heightened access to external financing as the main obstacle, demanding critical attention, especially if these industries are to grow and generate more jobs leading to economic growth.

Evidence in the literature reveals that 51% of small businesses in sub-Saharan Africa need additional capital than is currently accessible [13]. Undeniably, short of consistent funding instruments, woman-led enterprises are inept at making the required investments desirable for growth, leading to inertia, yet microfinancing credit instruments can assist firms in closing this critical gap. At the outset, formal woman-owned enterprises tend to be few, since they tend to focus on less profitable businesses. This continues to be a global challenge including the developed countries, where woman entrepreneurs are strenuous in the sales, retail, and service sectors [20], with small contributions in high-growth or high-technology sectors. For that reason, recent surveys display that woman-owned enterprises have inferior overall sales turnover and profit dimensions than male-owned firms. Thus, supporting female entrepreneurs, expressly those in high-growth sectors, has the potential to create more new jobs, raise profits, boost millions out of poverty, and lead to greater socio-economic transformation of society.

Although policymakers and academics have attempted to understand this, the role of microfinance support to woman-owned SMEs has been ill-explained.

In an effort to achieve the study objective, bibliographic data from Scopus and a systematic literature review approach were used to analyze a total of 402 open-access scientific journal articles written in English and published from 2003 to 2022. The Scopus database brings together the superior excellence and attention of many accredited scholarly international articles as well as cutting-edge analytics and business management in one solution that can ably combat predatory publishing and protect the integrity of the scholarly record. We intended to map out recent research trends and correlate cutting-edge study opportunities on microfinancing for woman-led enterprises in emerging economies in Africa. In addition to traditional bibliometric indicators such as published articles, we further considered commercial citations including underlying and impactful authors grounded on the number of publications and total citations acknowledged on top of their individual h-index values.

Earlier scholars revealed that encouraging female-owned enterprises to seek microfinance solutions such as personal loans and microfinance credit on flexible terms instead of commercial banks is critical to supporting the resilience of economies and new sources of growth [21,22]. Moreover, microfinance instruments allow low-income woman entrepreneurs to build credit habits that would enable them to become more bankable. Considering the important role played by microfinance products, policymakers and academics have deliberated on new financing approaches for early-stage firms that articulate the strengths of microfinance loans in nurturing MSMEs exclusively in rural community settings [22]. Notably, the last two decades have witnessed several government-supported policies and programmatic solutions on gender-focused financing of MSMEs, financial inclusion, and education as pathways to achieving national economic prosperity [4,13,23] Despite all these efforts, the results differ vividly by nation, and overall, the untapped potential of woman entrepreneurs remains a lost opportunity for economic growth that the world can ill afford. Additionally, the benefits these firms offer have been inadequately documented and detailed in the current literature to account for women’s full economic contribution. Therefore, this article was inspired by the growing frustrations of a lack of woman-led enterprises to access external financing to uphold their growth and progress in the current fragile business environment.

Furthermore, although these results appear impressive, woman entrepreneurs still encounter several obstacles in starting new businesses or expanding existing ones. Among other things, woman-led enterprises are constantly deprived of external financing, which ultimately impedes their potential to contribute to inclusive and sustainable growth [24]. Moreover, research shows that this is the foremost factor that explains the increasing failure of woman-owned enterprises from business. A study [23] in Zimbabwe states that many SMEs are excluded from the financial system because of their size in terms of capital and annual turnover, especially in rural communities, where these firms are perceived to be unbanked by mainstream financial service providers. Moreover, [18] reveals that MSMEs in developing countries face more challenges in accessing debt and equity finance than those in developed countries. These results are consistent with other studies [25,26,27] that indicated a lack of access to finance as the topmost cited obstacle to enterprise growth and development. Recent works [27,28] support the latter view, where they contend that SMEs in Uganda are still disproportionately affected by insufficient funding.

Conversely, other studies [14,15,17,18,19] dispute the positive impact of microfinance, stressing that microfinance is commercialized and has become more of a profit-generating activity instead of uplifting the economically productive poor from the vicious circle of poverty. Studies [29,30,31] have revealed that women are less likely to access external capital than men. Such variances result in misrepresentations in circumstances where women’s entrepreneurial activities are under-resourced and undercapitalized, thus reducing their inclusive economic growth. This is consistent with [32] from their study in China on new financial alternatives in seed entrepreneurship. They did not find any significant relationship between the use of formal finance and firm growth. Consequently, there has not been a consensus from prior literature about the effect of external finance on MSME growth, particularly in emerging nations wherein the mortality rate of MSMEs is alarming, with five out of seven new start-ups closing business in their first year of operations. Although some scholars have made considerable progress in offering internationally comparable data, substantial knowledge gaps still exist. No studies have been conducted in Uganda or East Africa, in general, that articulate the role of access to microfinance credit for the performance and growth of woman-owned enterprises. Several of these empirical surveys tend to offer generic conclusions that may inadequately expound the potency of the MSME segment to women’s economic emancipation in Uganda.

This article expressly directs attention towards devoting a systematic review of literature fundamental to underpinning the extent to which microfinancing approaches impact woman-led enterprises from an emerging economy perspective with unique attention on increasing their access to economic activities. To deliberate on the current standpoint on the nexus between microfinance and the growth of woman-owned enterprises, we performed a bibliometric analysis grounded on Scopus bibliographic data that facilitated building an anatomy and review of the understanding of the research question. By doing so, we essentially addressed three significant research aims. The first was to highlight the primary trends of microfinance solutions in connection to the growth of woman-led enterprises by presenting a chronological distribution of publications such as annual research outputs and journal articles by outstanding authors. Furthermore, this article extensively debates the academic structures of microfinance research outcomes and offers good policy implications to assist entrepreneurs and investors minimize the risks of investing in unviable enterprises. Finally, it partially fills current literature gaps and delivers future directions for research with the aim of deepening our understanding of this topic.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The first section debates recent research trends and literature development on the role of microfinancing for woman-owned small and medium-sized enterprises and economic growth. This is followed by a discussion on the research methodology used, and lastly, the results are explained and a discussion highlighting emerging trends and publications on the subject ensues. Finally, we offer vital conclusions that can be drawn from our analysis, highlight the limitations of the study, and provide direction for future research.

2. Research Trends and Literature Development

2.1. Role of Woman-Owned Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Economic Growth

Woman entrepreneurship has drawn vast attention from scholars and experts, with a large body of studies in recent years. Criticism has been leveled against previous scholarships for a lack of focus on women’s entrepreneurship and their frequent dependence on traditional methodological perspectives that often neglect bibliometric analytical methods. SMEs play a major role in the global economy, and increasing access to finance for woman-owned MSMEs is a good strategy for nurturing entrepreneurship, as it is critical in supporting economic growth and development. In the United States, woman-owned SMEs constitute 23% of MSMEs and contribute nearly 3 trillion USD to the economy, while in Canada, women own 47% of small enterprises and account for 70% of new venture creations [13]. Women’s substantial contribution to these industrialized economies demonstrates the direction many emerging nations can take to increase business opportunities for woman entrepreneurs. Albeit the average growth rate of woman-owned businesses in emerging markets is significantly lower than that of men, their growth potential is becoming evident. A recent account by [13,33] estimates about 31–38% (8 to 10 million) of formal SMEs in emerging markets have at least one woman founder member. Precisely, woman-owned SMEs produce impressive revenues in excess of 100,000 USD per annum, matching positively with those in the US. A previous survey of 1228 women in Bahrain, Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia, and the UAE found that women made significant contributions to their economies by handling reputable businesses, revenue generation, and job creation. A related study in Pakistan posits that microfinance programs focused on woman entrepreneurs contribute positively to the growing income and consumption levels of female debtors and create opportunities for the entire local community [19]. In the long run, women are economically empowered to afford life’s basic needs, which are important factors for the sustainable development of communities.

While we identify the works of earlier scholars on microfinancing progress, numerous literature gaps persevere. To begin with, [30] divulged that female entrepreneurs hardly received an equal share in entrepreneurial activities owing to persistent discrimination in access to different funding sources. It is also argued that gender inequality and unfavorable socio-economic perceptions impede the financing opportunities for female-led enterprises [34,35]. In the same line of thought, [36] emphasize that a lack of women’s entrepreneurial efficacy and resilience to venture into new business avenues are significant obstacles that deter the tendency of women to pursue business work. In addition, more academics have documented comparable results in current years [24,37]. In contrast, [1,13,29] revealed that the financial services delivered by MFIs were suggestively insufficient and unable to enhance the livelihood and progress of businesses owned by underprivileged woman entrepreneurs [38]. Amidst these mixed reactions, there is evidence to confirm that woman entrepreneurs in developing countries encounter much greater difficulties than their male counterparts, thus limiting their potential access to different sources of capital [39]. To this end, we engaged in a bibliometric analysis to highlight recent trends in this arena as a measure to aid policymakers, investors, and academics in surveying the benefits and setbacks of microfinance and to categorize pertinent zones of involvement.

Regardless of many empirical studies on the importance of access to finance for firm growth [14,15,17,18], only a handful have attempted to explore the impact of microfinance credit on the performance and growth of woman-owned enterprises [18,19,20,39,40], and amongst these few, not a single study paints a good picture of the situation faced by woman-owned enterprises in Uganda. Whereas SMEs encounter a series of barriers to their survival and inclusive growth, prior studies have heightened access to external financing as the main obstacle demanding urgent attention, especially if these industries are to grow and generate more jobs leading to economic growth.

Previous research into the financing of woman-owned businesses in similar developing countries proposed that woman entrepreneurs finance their businesses differently from their male entrepreneurs [18,39,40,41]. Male-owned SMEs are found to create superior use of external sources of finance, such as bank and personal loans and venture capital [25]. However, small woman-owned firms prefer personal savings for establishing a new business [18]. Despite everything, a few studies clearly demonstrate the impact of differential access to finance, especially with a unique focus on small woman-owned enterprises. Until now, this is an area where data have been little accessible. Such knowledge gaps offer a great opportunity for future research on this subject.

Furthermore, research shows that woman entrepreneurs face higher prejudicial attitudes from loan officers [21], because conventional financial institutions often demand extra collateral on bank credit, which woman entrepreneurs commonly lack [18]. Such collateral may be spousal co-signatures and land titles required for the same nature of credit accessed by male counterparts [21]. Existing studies offer a polaroid of a given state of affairs and not its origin. The literature that can support specific firm-level performance and large-scale conclusions about the growth of MSMEs with a focus on the gender of the founders/owners in developing countries is inadequate. Therefore, the direction of future research in this field can offer additional insights into the importance of increasing access to finance for woman-owned enterprises, including suggestions to improve on the model.

In contrast, the portfolio of financing instruments (loans and microcredits) available in developing countries is substantially lower than the target market segment of woman-owned SMEs [40,42], and the reasons for underserving this market segment are inadequately studied. Earlier scholars [14,15,16,17,18] have offered anecdotal conclusions supporting several limits and features of small woman-owned businesses. There is a consensus that a perception of higher risk and educational prejudice towards woman-owned MSMEs hinders their opportunities to receive microfinance credits from banks and MFIs [4,19].

Although such a link is well established, attention to the process of how entrepreneurs gain access to finance remains limited. In a rare instance, [43] identified strategies entrepreneurs employed to secure venture capital, demonstrating that success was closely aligned with the founders’ strong prior social network. While microfinance programs are focused on enhancing the recipient’s livelihood into a quality life through poverty alleviation, several disadvantaged women lack access to microcredit to start their own businesses. Consequently, current funding approaches seemingly do not address the principal purpose of alleviating poverty for a significant portion of poor women in emerging nations like Uganda.

Lately, microfinance models have drawn great attention from both policymakers and researchers, with some believing that they have substituted government programs as a main financing instrument for opening and fusing income-generating activities in nations with high microfinance support [44,45]. While policymakers and academics have attempted to understand microfinancing, the role of microfinance support to woman-owned MSMEs has been inadequately articulated. Moreover, while some scholars articulate the strength of the microfinance model for increasing access to funding for low-income woman entrepreneurs, existing funding techniques only address the demands of MSMEs that do not have much potential to contribute towards job opportunities or GDP per capita. Hence, microcredit to woman-owned SMEs in Uganda has remained grossly inadequate and disproportionate to market opportunities [29]. Therefore, future studies that attempt to contribute to knowledge in terms of increasing microfinance credit to woman entrepreneurs are an immediate necessity and must be accompanied by impact assessments of skills development that are essential to inspiring sustainable growth beyond microenterprise.

2.2. Influence of Microfinance on the Resilience and Growth of Woman-Owned Microenterprises

Many studies geared to specific countries explicate that offering continued financial access to woman-owned MSMEs and entrepreneurs positively impacts economic growth [13,21,27,41]. However, funding geared towards woman-owned MSMEs ought to be done with caution, since gender disparities in access to financial services have negative repercussions, not only for woman entrepreneurs but for the overall economy. Women’s participation in entrepreneurship has been at the forefront of aiding the growth of these economies as a measure to reduce social inequality as it relates to job creation, private sector development, and wealth creation, particularly in emerging economies categorized by restricted growth in employment [13,41]. Research shows that the creation and growth of small firms is smoothed in nations that deliver an enabling environment with relaxed access to finance [27,44,46]. It has been well documented that access to microfinance credit empowers existing firms to develop by taking advantage of growth and investment opportunities. Undeniably, access to capital can be critical for firm growth through the entry of new firms and the creation of a prosperous private sector with a well-organized supply of resources exclusively for small businesses.

2.3. Problems Facing Female Entrepreneurship and Woman-Owned Enterprise Development in East Africa

While there has been a growing interest in the external financing of woman-owned enterprises in recent years, policymakers and academics have raised serious concerns that the growth needs of woman-owned enterprises go beyond microfinance credits [44]. Research evidence demonstrates that some woman entrepreneurs typically have very good ideas; however, transforming such ideas into business reality necessitates higher loans, but again, female entrepreneurs are often discriminated against when seeking access to such loans [19,25], which negatively impacts their potential to create new MSMEs and grow sustainable businesses. Little evidence is available in the public domain to offer applied and theoretical solutions to this acute problem. This research thus attempts to contribute to the current literature with new datasets.

From this delineated literature, it appears essential to elucidate present academic concepts illuminating the exclusivity of the role of microfinance on woman-led enterprises as a self-determining study subject. Several scholars have voiced a strengthening call for microfinance instruments in addressing the financing gap of MSMEs as a reliable tool for reducing poverty. However, there is much criticism of the proficiency of microfinance loans in alleviating poverty. It is argued that microfinance loans are partially the broader problem rather than the solution because of unfavorable terms and high interest rates driving underprivileged communities into more economic pitfalls instead of prosperity [30]. In worst-case scenarios, it is alleged that microfinance borrowers may even commit suicide because of their inability to repay these loans. Specifically, the cost of serving a loan or microcredit in Uganda is sometimes 20–25% higher than in similar developing countries and about a fifth of SMEs in sub-Saharan Africa. High interest rates often deter SMEs from even applying for microfinancing loans [47]. This lack of affordable financing seriously hinders the growth of SMEs in Africa. In a bid to mitigate these challenges, a diversified financing model that creates an opening for venture capital, angel business, and crowdfunding would be a viable alternative approach to providing SMEs with access to the capital needed to grow.

In a nutshell, many woman entrepreneurs self-finance the growth of their business because they bootstrap through personal savings or receive investments from family and friends. These finance instruments are convenient for start-ups, but they are usually in limited supply. Although 75% of woman entrepreneurs struggle to seek equity financing, half of these women are often unsuccessful in receiving any financing from formal financial institutions [13,19]. From this perspective, it is important to evaluate how microfinance credits can be better exploited by female entrepreneurs to promote firm survival and prosperity.

3. Research Approach and Methodology

Data and Search Strategy

The primary source of our data was the Scopus database, with more than 27 million abstracts. It is currently the most used and widely accepted database in systematic bibliometric studies, with a highly reliable and consistent record in multidisciplinary research [45]. Bibliometric analysis is an interdisciplinary subject that applies data visualization procedures to create a quantitative analysis and summary of the indicators of authors, journals, countries, institutions, references, and keywords of worldwide literature in a certain field. We performed a bibliographic systematic search from the Scopus database in March 2023 for all articles published between January 2003 and March 2023, since they were considered valid sources of knowledge [48]. We applied keywords such as “microfinancing” AND “women” AND “entrepreneurship”, and then separated the articles based on titles, keywords, and abstracts to create a database of 4143 articles. Considering that this study was multidisciplinary, we limited the search to the fields of business management and accounting (35.6%), and econometrics, economics, and finance (29.4%) representing 65% of publications on microfinancing woman-owned enterprises globally.

On the other hand, we excluded all articles written in languages other than English, conference presentations, books, and thesis chapters. While this approach may pose a challenge where some critical scientific monographs were omitted, we are certain that this was the best approach to present excellent research of existing scientific contributions because it delivered robust and unwavering review procedures that are usually carried out in the academic arena [49]. This selection phase narrowed the field, producing a result of 402 scientific articles from the most influential authors on the subject and the most productive scientific journals with regard to the number of articles published. Briefly, the ultimate article collection was completed by means of the following inclusion standards.

- (1)

- We applied keywords such as “microfinancing” AND “women” AND “entrepreneurship”.

- (2)

- Select a search term, abstracts, title, and keywords.

- (3)

- Limit to economics, econometrics, and finance, as well as business management and accounting articles.

- (4)

- Open-access scientific journal articles from January 2003 to March 2023, written in English.

This approach allowed for the presentation of complex statistical data in a comprehensive visualization manner, essential for the exploration of any empirical data and for the communication of statistical results, such as the illustration of data comparisons, patterns, trends, and relationships.

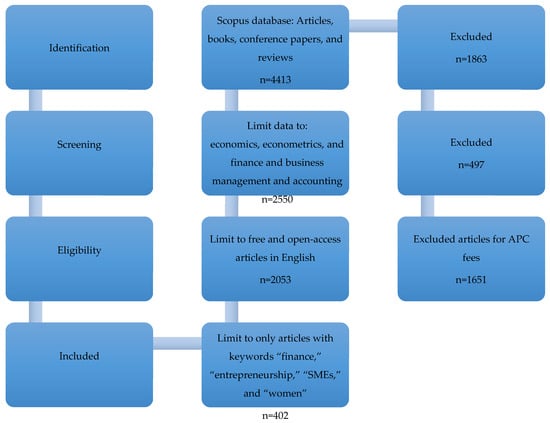

As can be seen in Figure 1, a total of 4413 publications, including journal articles, book chapters, conference papers, and reviews, were identified from the Scopus database from January 2003 to March 2023. The results revealed 2053 open-access articles published in English on the various themes of microfinancing. To narrow down our analysis to microfinancing and woman-owned enterprises, we excluded all keywords without a reflection of finance, small business enterprises, and entrepreneurship. However, keywords that indicated geographical regions and countries were included to identify countries with a footprint in microfinancing for woman entrepreneurship, which generated 402 keywords included in the bibliometric coupling analysis. Nearly all the open-access journal articles were written in English (2053 of 2092), implying that the analysis excluded any publications in languages other than English.

Figure 1.

Research approach to data screening (source: articles retrieved from Scopus database March 2023).

VOSviewer Version 1.6.19 software was used for data analysis, and search-term abstracts, titles and keywords were selected during the search for relevant data relating to the subject area of microfinancing and woman-owned enterprises, with a minimum co-occurrence of five keywords used. This type of analysis was chosen to contract a continuously expanding body of knowledge based on three major criteria—measurement of a specific scientific activity, its effects as carried by the total quantity of article citations, and the links amongst articles [50]—hence outlining the framework of the current understanding in a research arena regarding a specific theme. VOSviewer Version 1.6.19 software version 1.6.10 allowed for an extensive bibliometric graphic representation, identification, and classification of groups in an associated strategic matrix based on similarities and differences [51]. The analysis was carried out using descriptive statistics and meta-analysis to define the general landscape of woman-owned enterprises and economic growth arising from increasing access to microfinance credit in Uganda.

Although a qualitative analysis of the works might be prejudiced by the bias of the researchers, this technique has the proficiency to address these hurdles [52,53]. The approach to using specific keywords to search the data was to minimize the selection of biased data for the study. Moreover, the extensive data analysis using graphs and meta-analysis allowed us to obtain an in-depth understanding of the correlations between the variables, thus creating a better grasp of previous works in this research field.

4. Bibliometric Analysis

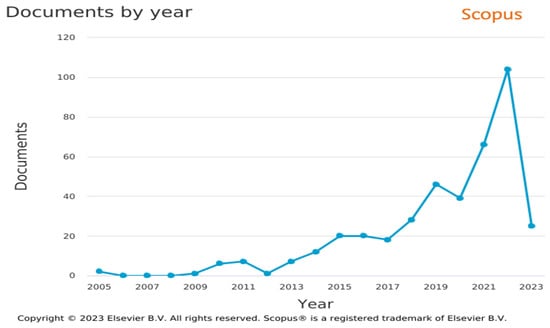

This section presents the results of the bibliometric analyses of the published articles from the different journals at the front line, using VOSviewer Version 1.6.19 data analytics software. Bibliometric analysis is an important research technique that plays a critical role in assisting researchers in identifying the academic structure of a definite ground of research, such as an opportunity to perform an extensive and structured literature analysis including editing of imported data from various databases [51,53], such as Scopus and Web of Science, among others. Reflecting on the content analysis results from January 2003 to March 2023 (Figure 2), there is evidence of linear growth in connection to microfinancing and woman entrepreneurship research.

Figure 2.

Published Scopus articles on microfinancing per year (2003–2023).

As can be seen in Figure 2, of the 402 open-access published articles in our screened dataset, the VOSviewer Version 1.6.19 software deduced that research on microfinancing for woman-owned enterprises seemingly started in 2005 with two peer-reviewed articles. We observed a slow progression of publications between 2005 and 2010, with merely 17 articles from the 402 analyzed. However, subsequent periods ranging from January 2010 to March 2023 indicate a skyrocketing growth in publications, with 385 articles (96.6%), largely in the spectra of economics, finance, business management, and accounting. The largest growth of publications was seen in 2022, with 104 articles published, while only two articles were published in 2005. Moreover, the first quarter of 2023 (January–March 2023) presented impressive results of 25 articles, suggesting an expected increase by the year’s end. We observed that the number of published papers was increasing year on year. These results are sufficient evidence to share the view that research on financing women’s entrepreneurship has drawn large attention from scholars.

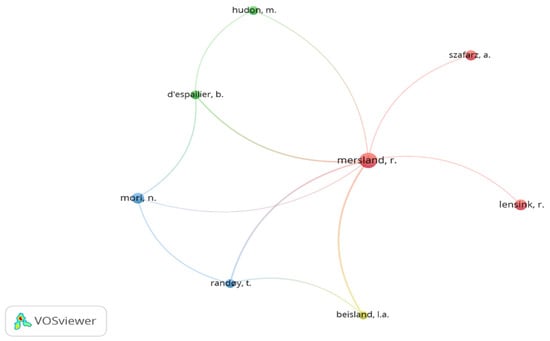

The bibliometric search for coauthors indicated 53 prolific authors from the 4517 authors who met the threshold, because many authors had low-link connection strengths. Moreover, only 8 of 53 revealed a strong network linking to the role of microfinancing instruments on woman-owned enterprises, as illustrated in Figure 3. Mersland produced the highest number of publications, with a total of 17 items connected and a total link strength of 17. The point to make is that these articles had a strong positive connection with the rest of the authors. Further analysis of the publications revealed that most of these authors were connected to emerging countries outside Africa.

Figure 3.

Analysis of connection of coauthors.

Bibliometric Co-Occurrence Analysis of the Nexus between Microfinancing and Woman Entrepreneurship

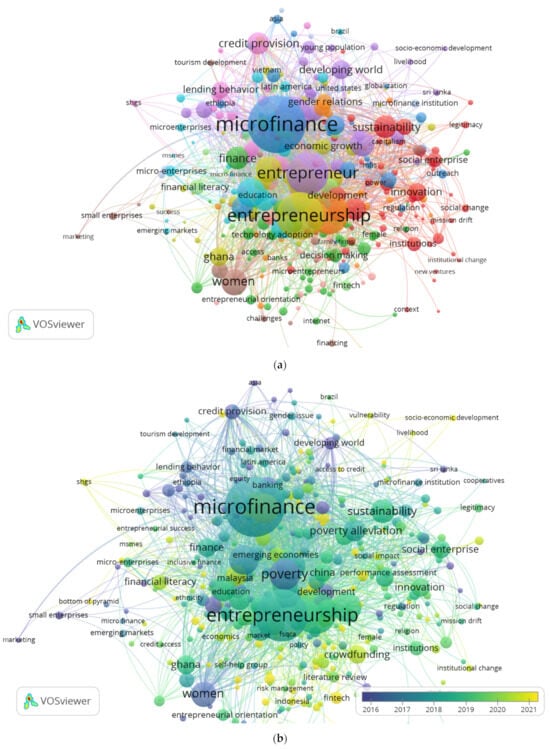

We used search terms such as “microfinancing” AND “women” AND “entrepreneurship” as our strategy to seek related data on the subject. Using a co-occurrence analysis approach, we limited the occurrence to a minimum of five keywords applied for data screening. This method generated a total of 398 full-strength works of 7050 that met the criteria. The downloaded articles embodied a vanguard of different published articles relating to the subject, categorized into five broad clusters as green, yellow, red, blue, purple, and brown.

As can be seen, network visualization mapping identified 12 clusters of journal articles using different colors in the visualization shown in Figure 4a. However, we ignored the small clusters and mainly focused on the six dominant themes illustrated by the larger circles and larger fonts of keywords, suggesting that the larger the nodes, the higher the frequency of occurrence. Additionally, red nodes and circles denote publications about sustainability and innovation approaches in the entrepreneurship ecosystem. The yellow clusters indicate studies based largely on entrepreneurship for economic growth, the blue nodes show topics on microfinance and access to credit financing, while the green circles demonstrate publications on financing female entrepreneurship with a strong network association with technology adoption, microentrepreneurial, and fintech firms. Similarly, the brown circles reveal networks of publications on women’s small enterprises. This means that these topics were the most debated by scholars from January 2003 to March 2023. Conversely, the unidentified keywords that did not have a strong network of association demonstrate potential fields for new research topics. It is also verified that the shorter the distance between the nodes, the larger the quantity of co-occurrence of keywords in the same publication. The blue cluster indicates that the topic “microfinancing” attracted the highest number of publications, while the yellow cluster illustrates various topics on entrepreneurship.

Figure 4.

(a) Bibliometric analysis of co-occurrence of keywords (dominant topics) on microfinancing and entrepreneurship (source: VOSviewer Version 1.6.19; Waltman and Van Eck, 2013) [50]. (b) Overlay visualization mapping for network strengths of the keywords about microfinancing and women enterprises.

Figure 4b reveals the network strength mapping of the different trends according to the keywords used. The nodes reveal the published articles extending from green, yellow, and purple colors. We observed that several studies that were recently published focused mainly on microfinancing approaches inclined towards enhancing entrepreneurship development, poverty alleviation, and sustainability, which are represented in a dominant green color. The purple circles reveal studies that were conducted with a definite linkage to microfinancing, such as poverty alleviation, women, and credit provisions. The point to make here is that since poverty is next to microfinance and entrepreneurship, these studies examined how microfinancing can enhance poverty alleviation and entrepreneurship in developing countries such as Ghana, Ethiopia, Malaysia, India, and Sri Lanka, among others.

The bibliometric overlay visualization illustrates the keywords associated with microfinancing publications, particularly those that co-occurred more than 10 times in the Scopus database, and were included in the final analysis. The magnitude of the circles denotes the frequency of co-occurrence. Of the 8487 keywords, 306 met the threshold. The dominant keywords in the analysis were “microfinance” (total link strength 2649), “entrepreneurship” (total link strength 2024), and poverty and empowerment (total link strength 1987). These conveyed a strong link to the field of microfinancing. Other topics like female entrepreneurship, innovation, sustainability, poverty alleviation, and economic development were also areas of concern, as they revealed a total link strength of more than 250 (Figure 4b). The distance between the two circles shows their correlation. Therefore, according to the results displayed in the network map, it is evident that more studies focused on entrepreneurship, microfinance, poverty alleviation, emerging markets, finance, sustainability, and women. Large circles represent researchers that have many publications, while small circles represent researchers with only a few publications in the subject area. It is evident that most of the articles were published in 2018 and 2019 (a total of 25 articles), and other articles were published in 2020.

Further analysis was conducted using the VOSviewer Version 1.6.19 fractional accounting approach to recognize the utmost influential occurrence of keywords to discover the most dominant topics relating to microfinance and women’s enterprises. These keywords were carefully chosen from the title and the abstract of each article or obtained directly from the keyword list of articles [51].

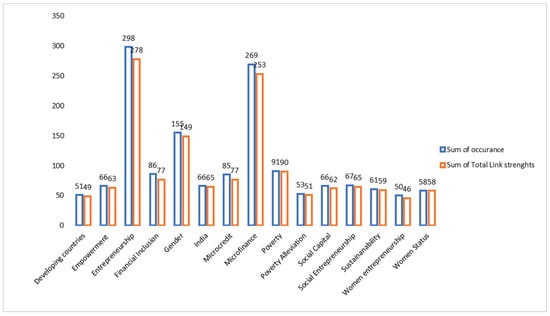

Figure 5 illustrates the most influential keywords in the 306 articles carefully chosen from the published articles from January 2003 to March 2023 that registered at least five occurrences. The graph demonstrates the total sum of occurrences for the dominant keywords matched to the total link strength. Our quick analysis revealed that entrepreneurship (298 occurrences) and microfinance (269 total keyword occurrences) were the most studied topics in the last two decades. It is evident that microfinance (253 total strength links) is highly linked to entrepreneurship (278 sum total strength links), gender (149 sum total strength links), poverty (90 sum total strength links), and microcredit and financial inclusion (77 sum total strength links).

Figure 5.

Analysis of dominant topics and total link strengths of keywords using the fractional accounting method between January 2003 to March 2023 (source: author compilation, 2023).

These findings illustrate the researchers’ efforts in examining the influence of microfinancing on entrepreneurship growth, access to microfinance based on gender equity, microcredit, financial inclusion, and poverty alleviation. All in all, the most influential topics included entrepreneurship, microfinance, ownership of SMEs in terms of gender, and poverty alleviation. This gives the impression that academics are paying significant attention to the nexus between entrepreneurship and microfinancing, particularly focusing on microcredit as an important instrument for encouraging female entrepreneurship with the latent empowerment of women from poverty.

We can thus conclude that microfinancing is a significant instrument in addressing these issues in emerging economies. However, topics that revealed a low occurrence of keywords and sum total link strengths presented potential areas for future research. These topics include, for instance, woman-owned enterprises (46 sum total link strength), microfinance studies in developing countries (49 sum total link strength), poverty alleviation (51 sum total link strength), and women’s reputation status in SMEs (58 sum total link strength).

5. Discussion of Results

5.1. Role of Woman-Owned Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Economic Growth

According to the Scopus dataset analysis results (Figure 2), there has been increasing growth in the number of published articles on the role of microfinancing instruments on new venture creation and sustainable growth of woman-owned small and medium-sized enterprises in the last two decades [24,28,54,55,56,57]. We observed that the period between 2005 and 2010 had few publications on microfinancing, with only 17 out of 402 articles published in the same period, topmost scholars included. Subsequently, the period ranging from 2010 to March 2023 saw skyrocketing growth in studies examining the influence of microfinancing on SME growth, with 385 articles (96.6%), largely in the spectra of economics, finance, business management, and accounting. The largest number of publications was 104 articles published in 2022. The first quarter of 2023 (January–March 2023) yielded 25 articles, a clear justification that research on microfinancing for woman-owned enterprises is increasingly gaining attention. We observed that the number of published papers was growing year on year.

Lately, growth in microfinancing of woman-led enterprise studies in emerging economies in Africa has drawn increasing attention from scholars, the business sector, and government organs. Thus, promising sustainable access to a series of microfinance credits to woman-led enterprises is crucial for fostering women’s economic freedom, the prosperity of community well-being, and poverty alleviation across developing countries [7,13,27,29,41,52,53], particularly towards achieving the sustainable development goals (SGDs). Recent studies expose that women’s economic participation has been identified as a significant factor in this outcome [13,57]. Similarly, the Boston Consulting Group shares the view that the vast socio-economic contribution made by woman entrepreneurs across the world to the global economy yields higher returns and tends to be more financially fruitful than the contribution by their male counterparts, making woman entrepreneurs a safe bet for investors and funders. A survey [7,13] reveals that Africa is the only continent where more women choose to become entrepreneurs. Although policymakers and academics have attempted to understand this, the role of microfinance support to woman-owned SMEs has been ill-explained.

Notwithstanding the several empirical studies on the importance of access to finance for firm growth [14,15,18], not many have attempted to explore the impact of microfinance credit on the performance and growth of woman-owned enterprises [18,19,20,40], and amongst these few, not a single study paints a good picture of the situation faced by woman-owned enterprises in East Africa countries. Although SMEs encounter a series of barriers to their survival and inclusive growth, prior studies have heightened access to external financing as the main obstacle, demanding critical attention, especially if these industries are to grow and generate more jobs leading to economic growth.

Evidence in the literature reveals that 51% of small businesses in sub-Saharan Africa need more capital than is currently accessible. Undeniably, short of consistent funding instruments, woman-led enterprises are inept at making the required investments desirable for growth, leading to inertia. For this reason, denying women SMEs access to reliable microcredit is certainly a huge barrier to creating employment, alleviating poverty, and growing the economy, yet microfinancing credit instruments can assist firms in closing this critical gap.

While the figure appears to be inspiring, articles that particularly focused on microfinancing for woman-owned enterprises were limited [17,23,54,56,58]. Even though the results give the idea that microfinancing has attracted significant interest from scholars across the globe, several of these studies were conducted in emerging countries outside Africa, and the results seem inconclusive on this topic [14,16,17,58], hence widening the literature gap in Africa. Particularly, the East African region revealed insufficient research efforts, with merely 7 of the 19 articles published between 2013 and March 2023. Ref. [28] investigated the financial inclusion and growth of small and medium-sized enterprises in Uganda, but did not offer a clear focus on female entrepreneurship. Ref. [14] also explored SME finance in Africa, but this also lacked special focus on woman-owned enterprises. Then again, [59] deliberated on enhancing climate change resilience through microfinance by redefining the climate finance paradigm to promote inclusive growth in Africa. It is, therefore, evidenced that these studies inadequately address the role of woman-owned small and medium-sized enterprises in economic growth, creating a fascinating direction for future research. Against this backdrop, these results are sufficient to conclude that the role of woman-owned small and medium-sized enterprises in economic growth is understudied. Therefore, researchers have a duty to explore this field of study and advance existing knowledge with respect to microfinancing and woman-owned enterprises.

5.2. Influence of Microfinance on the Sustainable Development of Woman-Owned Microenterprises

Bibliometric analysis and clustering methods were used to categorize data grounded on the subject classification of the literature and the development trends in microfinancing and woman-owned enterprises. To reduce inconsistencies arising from new data updates, we exported and saved data as RIS files. We identified high-frequency keywords as research hotspots, which are denoted by bigger fonts and green, as shown in Figure 4b using an overlay visualization mapping for network strengths on microfinancing and women enterprises. Previous scholars document that increasing access to microfinancing instruments has a positive impact on woman-owned enterprises [30,40,56,60,61].

While our search for data (authors and coauthors, co-occurrence of keywords) was protracted, from January 2003 to March 2023, we did not find any peer-reviewed articles published earlier than 2006. Additional publications were recorded from the year 2012 with evidence of 12 individual articles published. This phenomenon indicates that research on microfinancing for woman-owned enterprises has attracted extra consideration from academics in recent years, with more results being realized in this regard [17,37,40,44,45]

Therefore, woman entrepreneurship by itself attracted increasing scientific research in 2018, with a record of 12 individual peer-reviewed articles [57,62,63,64,65,66,67] and a continuous growth in subsequent years from January 2019 to March 2023 that recorded a total of 74 published articles. The main attention was directed to examining financial inclusion and the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises for poverty reduction in developing countries [4,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,29,41,42], while some scholars determined the impact of microfinance on microenterprise performance [19,40,43,60]. Unquestionably, these are considerable outcomes underpinning the effect of microfinancing on the growth of small firms. Nevertheless, our major interest was to diagnose how microfinancing instruments had shaped woman-owned enterprises, specifically in East Africa, for which earlier studies had seemingly neglected. Limited studies have attempted to investigate this subject, for instance, [60] examined the empowerment of women through microfinance banks in rural areas of Pakistan, while [40] analyzed the impact of microfinance on the performance of woman-owned microenterprises in Indonesia. Moreover, the results from attempts by earlier scholars are inconclusive on this subject.

While microfinance lending is progressively gaining attention as an appealing form of finance for young high-growth companies seeking growth, still, major hindrances to adapting this financing model persist [34,64]. Against this backdrop, accelerating sustained access to microfinancing is a do-or-die role in fostering the long-term growth of women small firms in developing economies. Earlier scholars confirm that easy access to finance solutions relates to significant prosperity in financial market growth, innovation, new venture creation, creation of new jobs, and internalization of companies [13,17,29,41].

In emerging countries, microfinancing has been observed as a significant puzzle and the biggest hindrance to high growth in entrepreneurship development [1,2,3,4,5,6]. SMEs have more significant problems compared to their counterparts, the large firms fluctuating from inapt technology, restricted worldwide markets, regulatory rules that impede growth, and most importantly, access to financial sources through the traditional banking system [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Consequently, a restricted quantity of SMEs including woman-led enterprises transform effectively into high-growth firms [17].

It is reported in current research that the necessary level of microfinancing in East Africa is still inadequate when compared to developed nations. This is attributable to the less developed financial sectors of countries in sub-Saharan Africa except South Africa [25,26,27,46]. South Africa is endowed with the most developed financial markets in the region. Nonetheless, there appears to be a mismatch when compared with its entrepreneurship and small-enterprise sector, which is manifested in the increasing fallout of SMEs in business. Such a trend contradicts the concept of a developed financial market often associated with financial independence and the creation of high-growth entrepreneurship, for example, in the US, Germany, the UK, and Switzerland.

Similarly, Kenya appears to boast much more developed financial markets in the East Africa region [27,29], but again, in Uganda and Rwanda, more work needs to be done to improve their securities markets. Specifically, Uganda has only 17 companies listed on the securities exchange, and 8 of 17 are cross-listed on the Nairobi securities exchange [65], comprising 9 locally listed and 8 cross-listed from the Nairobi Stock Exchange in Kenya. The findings of [66] exposed that only four companies were listed on the Kigali securities market in 2013. Surprisingly, both Rwanda and Uganda have not registered any initial public offering exits from VC financing. To this end, government and private sector efforts that are geared towards increasing microfinancing options for the HGFs cannot be overlooked.

Several attempts have been made to introduce other alternative financing sources to bridge the equity gap of SMEs, such as crowdfunding commonly, hailed as a favorable funding approach to early-stage firms [32]. It is alleged that small firms that have received crowdfunding in their early stages are likely to attract VC firms and business angels. All the same, small firms face challenges in an attempt to bridge the financing gap in later stages of growth and expansion [34,35,36]. The prevailing consensus in the research field is that VC constitutes an essential part of the ecosystem for young and innovative start-ups [68]. Hence, an exploration of alternative innovative financing options for SMEs to help bridge the financial gap is more important than ever. As a result, these firms must get a chance to be funded by VC firms to assist them in realizing their growth and market internationalization [52].

5.3. Problems Facing Female Entrepreneurship and Woman-Owned Enterprise Development in East Africa

This section presents publication trends on microfinancing regarding female entrepreneurship. Whereas the results in the preceding sections depict a substantial growth in the annual scholarship on microfinance and SME growth, several hindrances have been observed and are accountable for the miserly growth of woman-owned enterprises [4,10,18,33,40,69]. This growing trend in publications may be elucidated by collective concerns around enhancing access for female entrepreneurship through microfinance. Especially, significant research consideration is preceded on varied reasons: first, the general consensus amongst scholars is that female-founded start-ups have lesser access to financing alternatives than male-owned firms which is attributable to several issues in common with gender partiality in undertaking funding choices, limited female role models with viable companies, gender-based stereotypes, and few female business entrepreneurs with dependable entrepreneurial skills [5,18,28,70].

Furthermore, we also discovered from an analysis of recent literature that the proportion of women who select to start and generate their own firms or contribute to business processes at a board level regrettably remains small when compared with their male counterparts [71,72]. Several prior scholars document gender-based bias in investment decision-making as one of the primary justifications for why female-founded firms are less attractive to venture capitalists, microfinance, and bank loan investors [73]. Empirical studies have exposed that male investors are more likely to invest in male-led start-ups, notwithstanding the viability of the business plan. Certainly, such unsubstantiated bias stands to elucidate why female-founded start-ups are repeatedly unnoticed or not granted similar levels of funding and mentorship as male-founded start-ups. It is also expected that this kind of inequitable funding approach grounded on gender instead of entrepreneurial experience and performance may result in the skepticism of female entrepreneurs when seeking funding, hence, deterring their likelihood of receiving entrepreneurial finances.

Evidence of data extracted from the Scopus database revealed 93 individual articles published from January 2003 to March 2023. On the contrary, a large class of woman entrepreneurship attracted the least surveys in the 20 years. Previous research claims that most female entrepreneurs are “unbankable” because of the high risks involved. Many woman-owned enterprises lack good financial records to inspire lenders, especially MFIs, looking to maximize profits through high interest rates. Moreover, and the worst scenario, even the banks do not have trust in such informal sectors. As a result, woman entrepreneurs received less attention than their men counterparts. Furthermore, unlike male entrepreneurs, female entrepreneurs in emerging economies, Uganda inclusive, often participate in MSMEs that mostly do not mature into established high-growth firms based on their inability to attract the different streams of microfinancing. Refs. [30,74,75] highlighted the difficulties faced in finding alternative support from financial institutions coupled with the fear of business failure and unfavorable social perceptions as important barriers that hinder the propensity of women to pursue a business career. Other authors [5,18,28] have reached similar conclusions in recent years. Ref. [60] contend that empowering women through microfinance support centers, especially in rural settings, is central to economic growth and development. However, woman entrepreneurs seemingly have limited knowledge about business and financial resources, thus proving it difficult to create and run businesses efficiently.

Evidence from the bibliometric analysis revealed that previous research focused on financing SMEs at large, and gender-focused microfinancing had not received great attention. Cognizant of the important role woman entrepreneurs play in creating jobs and their immense contribution to society’s well-being, particularly in increasing the family’s disposable income, there is enough evidence to claim that increasing microfinancing supply to woman-owned enterprises and entrepreneurs is a reliable pathway to realizing society’s economic freedom and poverty alleviation [18,21,40,44,76].

In spite of the vibrant and immense business prospects for investing in early-stage enterprises, the economic potential of female entrepreneurs and business leaders remains unresolved. One of the outstanding obstacles to their success is that female entrepreneurs have less access to finance than their male counterparts. In developing economies, woman-owned SMEs have a financing gap of about 1.5 trillion USD [6]. On account of this, mentorship and increasing access to microfinancing credit is essential to nurture women in entrepreneurship. In recent years, the demand to empower women and fight poverty in a bid to contribute to the SDGs has provoked the interest of political and international development partners along with encouraging women to become independent entrepreneurs [21].

6. Conclusions and Future Research Agenda

Woman entrepreneurs have been recognized for the central role they play in economic growth and development. This article hinges on a bibliometric approach to elucidate the recent developments and trends in financing woman-owned enterprises and how the field is anticipated to transform into new financial technological progress over successive years. The knowledge maps attained through VOSviewer Version 1.6.19 offer an outstanding basis of knowledge from the documents published and deliver future research pathways to imminent academics concerned with the aforesaid field. The key findings expose that microfinancing support services for woman entrepreneurs are fundamental for the uninterrupted productivity and growth of woman-owned enterprises since a large number of these firms lack access to sustainable funding mechanisms when compared to male-owned firms. This concept has received strong support from primary authors from Asia (for instance, [33,43,69,70,77] and a limited number of scholarships from Africa [18,28,40]. Therefore, it is important that financial institutions and international development agencies pay great attention to increasing access to finance for woman-led businesses along with distinguishing the role women play in contributing to the SDGs, particularly economic empowerment and global climate change to fragility.

From a different standpoint, some authors have found microfinancing loans detrimental to nurturing woman-owned enterprises. Specifically, [30] relayed that MFIs extort large sums of money from microcredit recipients (woman entrepreneurs) in the form of high interest rates. Thus, many woman-owned enterprises that acknowledged this nature of financial support have realized nominal business prosperity. Similarly, leading scholars from China, Pakistan, and Nepal have offered comparable results, yet these articles offer remarkable research records in impact journals and among the articles which have drawn enormous citations globally.

Whereas microfinancing institutions have been hailed for contributing towards poverty alleviation and economic growth in emerging economies, a large number of woman entrepreneurs cannot afford microcredit due to the unfavorably high interest rates and a lack of mentorship prior to accessing microfinancing resources [78]. To guarantee apt loan refunds to the bank, employees and loan recipients impose intense pressure on women clients. This matter is specifically severe in the developing economies of Africa; yet the continent presents the highest populace of underprivileged women desperately in need of economic empowerment. Worse still, inadequate information about business and financial materials makes it extremely challenging for woman entrepreneurs to start and run businesses efficiently. To avert this trend, there is a growing demand for the mentorship of woman entrepreneurs, as well as financial inclusion, to ensure that the women’s business sector is not overlooked amidst fast changes in technology. Even though IFC has recognized the role of woman-led SMEs, and mobilized funding of over 4 billion USD as of January 2023, including providing technical expertise to 154 financial institutions in 68 countries to launch profitable value propositions for women customers, the results are yet to be seen.

All in all, while microfinance services are considered an entry point or a vehicle toward empowering women, MFIs extort money from poor women through high interest rates, causing increased social pressure and in some cases leading to domestic violence [30]. Microfinance services have been, and are increasingly becoming, a popular intervention against poverty in developing countries, generally targeting poor women. It has been considered an effective vehicle for women’s empowerment [79]. The empowerment of women is a global challenge since traditionally women have been marginalized and subjected to the control of men. About 70% of the world’s poor are women [19] and approximately 60% of women in Tanzania live in abject poverty where they have no access to credit and other financial services. In addition, due to their low education level, their knowledge and skills on how to manage their work is generally low.

Furthermore, we also discovered from the analysis that the proportion of women who start and generate their own firms or contribute to business processes at a board level, regrettably, remains small when compared to that of men [80]. Several prior scholars document that gender-based bias in investment decision-making is one of the primary justifications for why female-founded firms are less attractive to venture capitalists, microfinance, and bank loan investors [73]. Empirical studies have exposed that male investors are more likely to invest in male-led start-ups, regardless of the feasibility of the business plan. Certainly, such unsubstantiated bias stands to elucidate why female-founded start-ups are repeatedly unnoticed or not granted similar levels of funding and mentorship as male-founded start-ups. It is also expected that this kind of inequitable funding approach grounded on gender instead of entrepreneurial experience and performance of the potential entrepreneurs may result in the skepticism of female entrepreneurs when looking for funding, hence deterring their likelihood of receiving entrepreneurial finances.

While the figure appears to be inspiring, the articles that particularly focused on microfinancing for woman-owned enterprises were limited [23,24,54,56,58,81]. Even though the results give the idea that microfinancing has attracted significant interest from scholars across the globe, several of these studies were conducted from emerging countries outside Africa. Even those few studies are seemingly inconclusive on this topic [15,16,58], hence widening the literature gap in Africa. Particularly, the East African region revealed inadequate research efforts, with merely 7 of the 19 articles published between January 2013 to March 2023. Moreover, we also discovered that many surveys about woman-led enterprises were merely restricted to CEOs of multinational corporations, and hence female leaders of early-stage enterprises are eliminated in this context. Consequently, an expansion beyond referring to women’s leadership would assist in capturing many woman-led enterprises that are regularly not studied.

As we conclude, the bibliometric results obtained from the co-occurrence and overlay visualization maps demonstrated a strong relationship between microfinancing mechanisms and nurturing woman-owned enterprises on top of entrepreneurship and poverty alleviation, for which the economic role is enduring. Thus, the growing interest in methodical studies confirms linear progress in microfinancing as a pathway to women’s entrepreneurship development. We trust that our analysis may offer great openings for scholars to identify the utmost existing trends in the literature on woman entrepreneurship frontiers.

7. Limitations and Future Research Direction

Notwithstanding the vast citations from Scopus and Web of Science databases that are broadly used in bibliometric research, they are exposed to numerous limitations, for instance, inter alia, restricted or prejudiced topical attention, partial subject indexing sustenance, publication bias by choosing journals and publishers alleged to be of “high impact”. Precisely, although the bibliographic analysis was led using the Scopus database involving over 27 million citation databases of peer-reviewed literature, including scientific journals, books, and conference proceedings, the study only focused on open-access peer-reviewed journals in English, yet the availability of open-access databases is commonly expensive, due to high subscription costs and compliance issues which makes it hardly affordable for organizations to subscribe to both commercial citation indexes. On account of the insufficient availability of high-quality open-access bibliographic databases for research articles, the opportunity to synthesize data delivered by small organizations is hampered. Despite the biases and limitations linked to these databases, Scopus and Web of Science are the most well-structured commercial citation indexes, largely accessible and trusted by several authors [53]; thus, these limitations do not inexorably weaken the authority of the findings. We, therefore, advocate for the expansion of open-source catalogs or the availability of databases to enable evidence synthesis and to decrease bias in how data are indexed and found. In addition, we also propose that future research conducts an extensive bibliometric analysis by means of both Scopus and Web of Science databases to complement these results.

Furthermore, the bibliographic data collection for the study was also confined to cited references as evidence of research articles existing in the fields of business management and accounting (35.6%) and econometrics, economics, and finance (29.4%) since microfinancing for woman-owned enterprises is closely related to business orientation. The propensity to choose research articles that support the authors’ own standpoint, particularly where the study took the direction of the aforementioned research fields, may lead to a disturbed assessment of the extant works. This study’s approach may eliminate merely beneficial journal articles, books, and conference proceedings in the fields of social sciences, psychology, and agricultural sciences given that microfinancing is a multidisciplinary subject cutting across various study settings. That said, to engender effective and consistent findings, it was inevitable to draw a line and eliminate journal articles that failed to meet our criteria. But, as mentioned, this approach was based on the authors’ personal judgment which sometimes may be associated with bias. Nonetheless, our results were largely supported by a flourishing co-occurrence of keywords like “microfinancing,” “microcredit,” and “entrepreneurship” from the methodical literature retrieved from bibliographic databases, justifying our categorical choice to investigate microfinancing and female-led enterprises through the lens of business management and accounting, econometrics, economics, and finance.

From a different standpoint, the process of retrieving data from the different databases may also depend on the content openness limits and readiness to download and export data. We observed that Scopus searchable bibliographic databases are restricted largely to previously published articles. In view of the comparatively meagre coverage of books and conference proceedings by Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholars arising from their primary devotion to journal articles, wherein Scopus generated over 4143 documents but only 4% accounted for books, conference papers, book chapters and the rest were journal articles, which is a clear justification of biased publications in commercial large databases. Such databases tend to limit the number of reproducible results (e.g., reviews, books, book chapters, conference proceedings reviews, editorials) and ultimately restrict access to this kind of data. While the orthodox narrative analysis commonly suffers from a lack of systematic means of circumventing bias, popular end-users of bibliometric databases seemingly are not typically conscious of these limitations and how they can affect the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of their findings. A good number of bibliometric users lack the required capability to select the most suitable choice amongst the different databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar Extra. For this reason, authors expecting to use a bibliometric analysis approach ought to empirically gauge and prudently select the most suitable bibliometric indicators essential for generating consistent and reliable results [53,60,61].

To conclude, this study submits to a positive future research direction such as microfinancing as an instrument for the economic empowerment of women and poverty alleviation in rural communities as a pathway to achieving the SDGs. Since the current study is restricted to the Scopus database, we trust that future studies can engage bibliometric analysis through an integration of both Scopus and Web of Science databases to generate comparable results about the reputation of this subject between emerging countries in Africa and developed economies. Furthermore, this study might serve as an impetus to interest scholars to conduct further studies in the continuum of microfinancing for female-led enterprises and their implications for community well-being in emerging economies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the College of Economic and Management Science Research Ethics Review Committee of the University of South Africa on 22 March 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found using VOSviewer version 1.6.19, in the domain of Economics, Finance, and Business management using keywords like microfinance AND entrepreneurship.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abebe, A.; Kegne, M. The role of microfinance institutions on women’s entrepreneurship development. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermes, N.; Hudon, M. Determinants of the Performance of Microfinance Institutions: A Systematic Review. In Contemporary Topics in Finance: A Collection of Literature; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 297–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubfal, D.J. What Works in Supporting Women-Led Businesses? 2023. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/38564 (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Cabrera, E.M.; Mauricio, D. Factors affecting the success of women’s entrepreneurship: A review of literature. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2017, 9, 31–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, E.; Dhakal, C.; Love, I. Female Entrepreneurs: How and Why Are They Different? World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cull, R.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. The Microfinance Business Model: Enduring Subsidy and Modest Profit. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2018, 32, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Access to Finance for Female-Led Micro, Small & Medium-Sized Enterprises in Bosnia and Herzegovina March 2018; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Investment Bank Report, Funding Women Entrepreneurs: How to Empower Growth European Investment Bank. 2021. Available online: https://www.eib.org/en/press/all/2020-167-new-report-funding-women-entrepreneurs-how-to-empower-growth (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Glennerster, R.; Kinnan, C. The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2015, 7, 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekola, P.O.; Olawole-Isaac, A. Hindrances to women entrepreneurship and development in Nigeria: Eradicating feminization of poverty among Nigerian women. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2014, Valencia, Spain, 13–14 May 2014; Volume 1, pp. 3196–3207. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S.; Uddin, M.H.; Tajuddin, A.H. Knowledge mapping of microfinance performance research: A biblio-metric analysis. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2021, 48, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Moid, S. Closing the Credit Gap in Women-Owned SMEs for Societal Transformation: A Theoretical Assessment of Indian Scenario. Aweshkar Res. J. 2017, 22, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- IFC. Strengthening Access to Finance for Women-Owned SMEs in Developing Countries; ‘IFC’ World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.; Cull, R. SME Finance in Africa. J. Afr. Econ. 2014, 23, 583–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donou-Adonsou, F.; Sylwester, K. Financial development and poverty reduction in developing countries: New evidence from banks and microfinance institutions. Rev. Dev. Finance 2016, 6, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahn, D.; Lecuna, A.; Chavez, G.; Barros, S. Drivers of growth expectations in Latin American rural contexts. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Guin, B.; Kirschenmann, K. Microfinance Banks and Financial Inclusion. Rev. Finance 2016, 20, 907–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wokabi, V.W.; Fatoki, O.I. Determinants of Financial Inclusion in East Africa. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 7, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Khan, F.A.; Violinda, Q.; Aasir, I.; Jian, S. Microfinance Facility for Rural Women Entrepreneurs in Pakistan: An Empirical Analysis. Agriculture 2020, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L. Measuring financial inclusion: Explaining variation in use of financial services across and within countries. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2013, 2013, 279–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. New Approaches to SME and Entrepreneurship Financing: Broadening the Range of Instruments; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavitis, C.; Filatotchev, I.; Kamuriwo, D.S.; Vanacker, T. Entrepreneurial finance: New frontiers of research and practice: Editorial for the special issue Embracing entrepreneurial funding innovations. Ventur. Cap. 2017, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoni, N.; Mwai, R.; Redda, T.; van der Zijpp, A.J.; Van der Lee, J. White Gold: Opportunities for Dairy Sector Development Collaboration in East Africa (No. 14-006); Centre for Development Innovation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Diebolt, C.; Perrin, F. From Stagnation to Sustained Growth: The Role of Female Empowerment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, F.; Krylova, Y.; Ramalho, R. Women’s Entrepreneurship: How to Measure the Gap between New Female and Male Entrepreneurs? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah, M.A. Determinants of SME growth: An empirical perspective of SMEs in the Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. J. Bus. Dev. Areas Nations 2021, 14, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, A.I.; Tsoka, G.E. Impact of venture capital financing on small- and medium-sized enterprises’ performance in Uganda. South. Afr. J. Entrep. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eton, M.; Mwosi, F.; Okello-Obura, C.; Turyehebwa, A.; Uwonda, G. Financial inclusion and the growth of small medium enterprises in Uganda: Empirical evidence from selected districts in Lango sub-region. J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Kratzer, J. Empowering women through microfinance: Evidence from Tanzania. J. Entrep. Perspect. 2013, 2, 31–59. [Google Scholar]