The Influence of Influencer Marketing on the Consumers’ Desire to Travel in the Post-Pandemic Era: The Mediation Effect of Influencer Fitness of Destination

Abstract

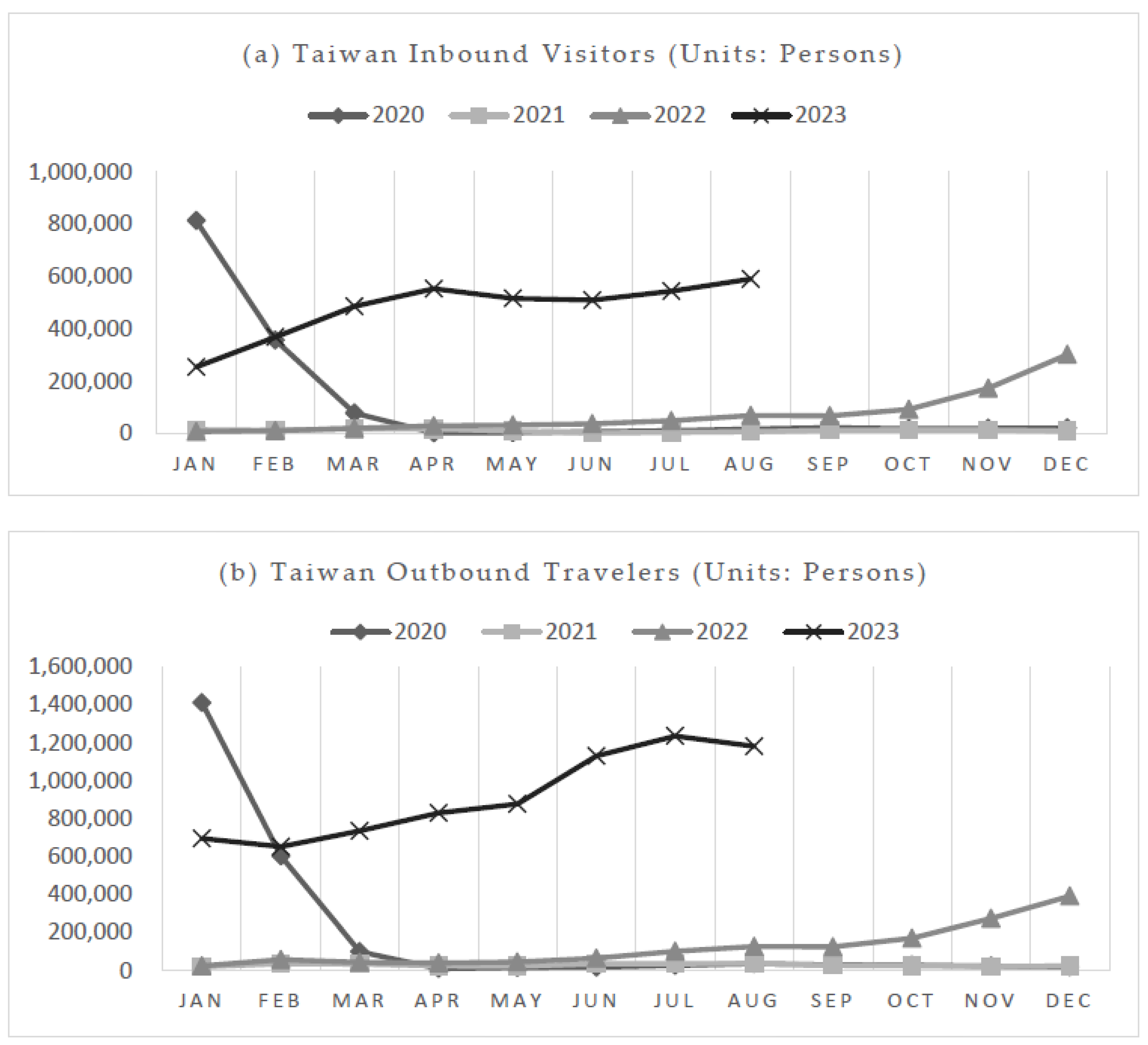

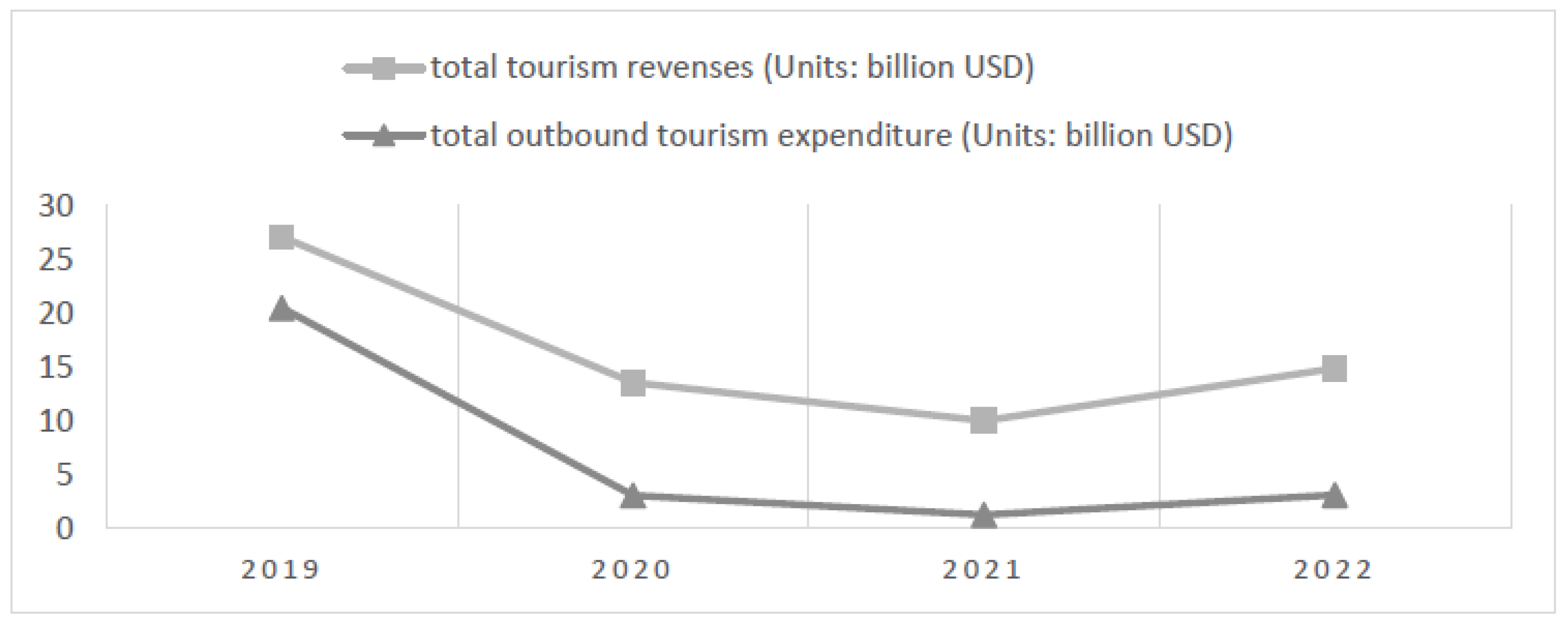

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Content

2.2. Fitness of Destination

2.3. Perceived Value

2.4. Desire to Travel

2.5. Theoretical Foundations

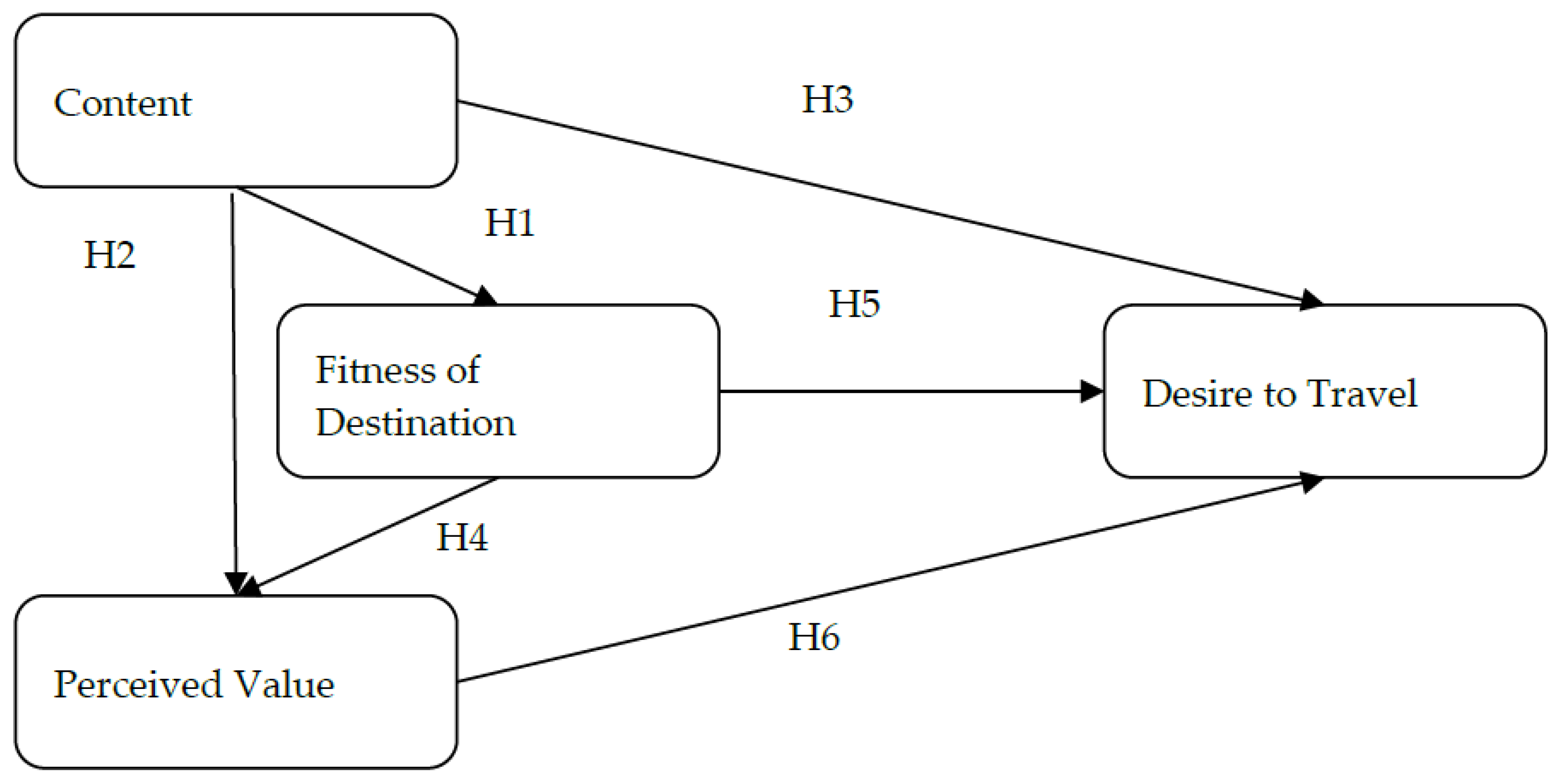

3. Research Framework and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Content and Fitness of Destination

3.2. Content and Perceived Value

3.3. Content and Desire to Travel

3.4. Fitness of Destination and Perceived Value

3.5. Fitness of Destination and Desire to Travel

3.6. Perceived Value and Desire to Travel

4. Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Demographics of Respondents

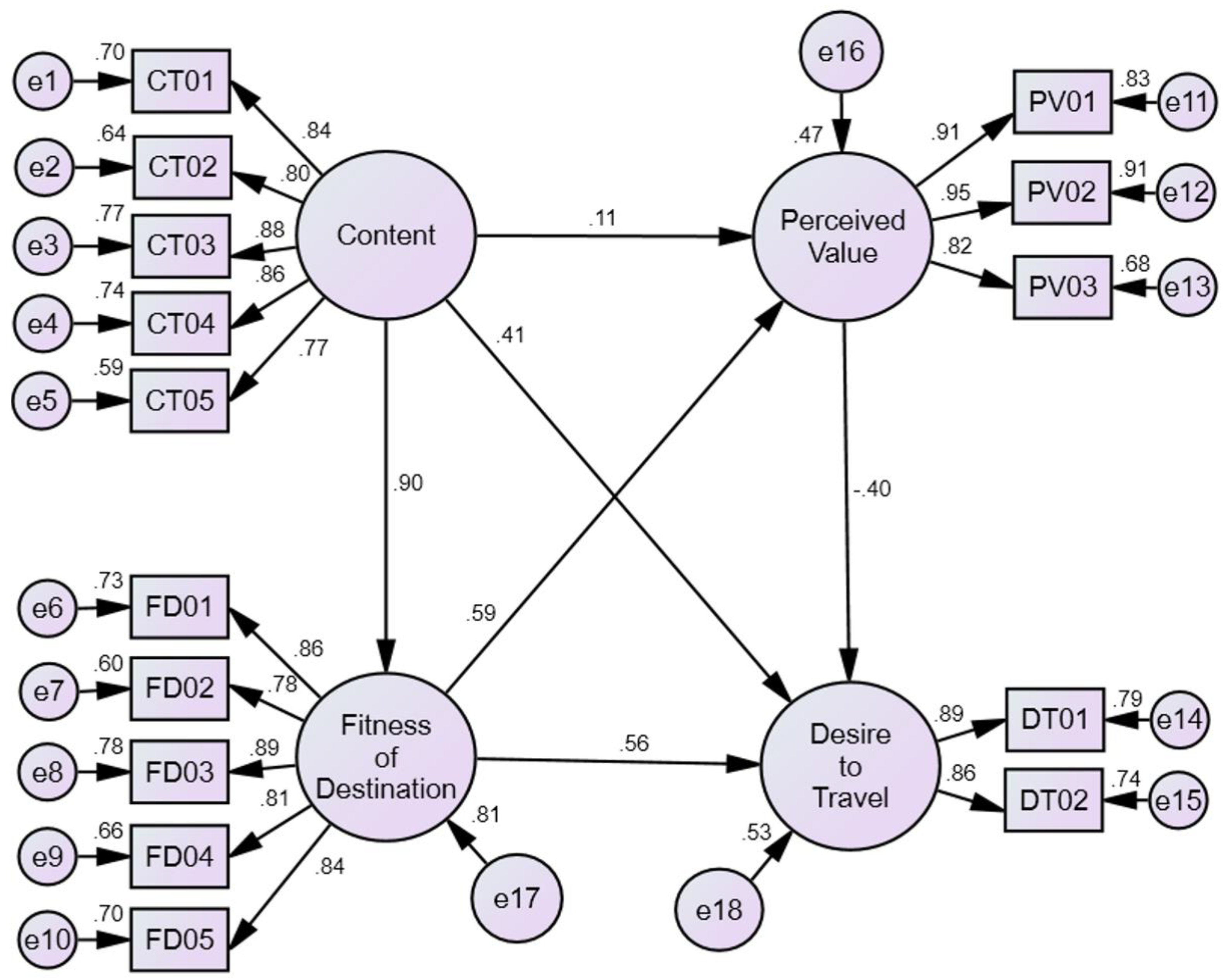

5.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.3. Pearson Correlation and Discriminant Validity

5.4. Structural Equation Model

6. Discussion and Managerial Implications

6.1. Discussion of Findings

6.2. Managerial Implications

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tourism Statistics Database of the Tourism Administration, MOTC. Available online: https://stat.taiwan.net.tw/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Tourism Administration, MOTC. Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/businessinfo/FilePage?a=14032 (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Opening Government Data Platform (Data.gov.tw). Available online: https://data.gov.tw/dataset/151521 (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Financial Statistical Database. Available online: https://web02.mof.gov.tw/njswww/WebMain.aspx?sys=100&funid=defjspf2 (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Kemp, S. Digital in 2018: World’s Internet Users Pass the 4 Billion Mark; We Are Social: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://wearesocial.com/blog/2018/01/global-digital-report-2018 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Pachucki, C.; Grohs, R.; Scholl-Grissemann, U. Is nothing like before? COVID-19–evoked changes to tourism destination social media communication. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Fang, C.; Lin, H.; Chen, J. A framework for quantitative analysis and differentiated marketing of tourism destination image based on visual content of photos. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boto-García, D.; Baños-Pino, J.F. Social influence and bandwagon effects in tourism travel. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 93, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Bruning, P.F.; Swarna, H. Using online opinion leaders to promote the hedonic and utilitarian value of products and services. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVeirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, R.; Iacobucci, S.; Pagliaro, S. The effect of influencer-product fit on advertising recognition and the role of an enhanced disclosure in increasing sponsorship transparency. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, L.; Dou, W.; Liang, L. Post, eat, change: The effects of posting food photos on consumers’ dining experiences and brand evaluation. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 46, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräve, J.-F. Exploring the perception of influencers vs. traditional celebrities: Are social media stars a new type of endorser? In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Social Media & Society, Toronto, ON, Canada, 28–30 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and Youtube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Theokary, C. The superstar social media influencer: Exploiting linguistic style and emotional contagion over content? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Be creative, my friend! Engaging users on Instagram by promoting positive emotions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, P.L.; Liebers, N.; Abt, M.; Kunze, A. The perceived fit between Instagram influencers and the endorsed brand: How influencer-Brand fit affects source credibility and persuasive effectiveness. J. Advert. Res. 2019, 59, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.-Y. Influencer advertising on social media: The multiple inference model on influencer-product congruence and sponsorship disclosure. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosanuy, W.; Siripipatthanakul, S.; Nurittamont, W.; Phayaphrom, B. Effect of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) and perceived value on purchase intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of ready-to-eat food. Int. J. Behav. Anal. 2021, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N.; Dini, B.; Manzari, P.Y. Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination, and travel intention: An integrated approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, C.; Cownie, F. An investigation into viewers’ trust in and response towards disclosed paid-for-endorsements by YouTube lifestyle vloggers. J. Promot. Commun. 2017, 5, 110–136. [Google Scholar]

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitan, S.; van Esch, P.; Soma, V.; Kietzmann, J. Influencer Marketing and authenticity in content creation. Australas. Mark. J. 2021, 30, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Belanche, D.; Fernández, A.; Flavián, M. Influencer marketing on TikTok: The effectiveness of humor and followers’ hedonic experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, C.; Holmes, G.; Strutton, D. Exploring the relationship between celebrity endorser effects and advertising effectiveness: A quantitative synthesis of effect size. Int. J. Advert. 2008, 27, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.; Vieira, I.; Pedro, M.I.; Caldas, P.; Varela, M. Patient satisfaction with healthcare services and the techniques used for its assessment: A systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.P.; Sutton, S.; Hennings, S.J.; Mitchell, J.O.; Wareham, N.J.; Griffin, S. The importance of affective beliefs and attitudes in the theory of planned behavior: Predicting intention to increase physical activity. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 1824–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipka, M. Selecting the Right Influencers: Three Ways to Ensure Your Influencers Are Effective. Forbes, 2017. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2017/11/17/selecting-the-right-influencers-three-ways-to-ensure-your-influencers-are-effective/#773b08677b47(accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Campbell, M.C.; Warren, C. A risk of meaning transfer: Are negative associations more likely to transfer than positive associations? Soc. Influ. 2012, 7, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.; Ferreira, D.; Pedro, M.I. The satisfaction of healthcare consumers: Analysis and comparison of different methodologies. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2022, 30, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.; Soares, R.; Pedro, M.I.; Marques, R.C. Customer satisfaction in the presence of imperfect knowledge of data. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 30, 1505–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.; Marques, R.C.; Nunes, A.M.; Figueira, J.R. Customers satisfaction in pediatric inpatient services: A multiple criteria satisfaction analysis. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 78, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depoux, A.; Martin, S.; Karafillakis, E.; Preet, R.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Larson, H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Esch, P.; Cui, Y.; Jain, S.P. The effect of political ideology and message frame on donation intent during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, P.A.; Gomes, L.F.; Caldas, P.; Varela, M.; Ferreira, D.C. Assessing the traveling risks perceived by south african travelers during pandemic outbreaks: The case of COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Marques, R.; Nunes, A.; Figueira, J. Patients’ satisfaction: The medical appointments valence in Portuguese public hospitals. Omega 2018, 80, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappi, S.; Montanari, F. The role of social identification and hedonism in affecting tourist re-patronizing behaviours: The case of an Italian festival. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Sun, J.; Asswailem, A. Attractive females versus trustworthy males: Explore gender effects in social media influencer marketing in Saudi restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 103, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Rastegar, R.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Hall, C.M. A framework for understanding media exposure and post-COVID-19 travel intentions. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 48, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; de Kerviler, G.; Guidry Moulard, J. Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | CT01 | 0.839 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.918 |

| CT02 | 0.800 | ||||

| CT03 | 0.879 | ||||

| CT04 | 0.863 | ||||

| CT05 | 0.769 | ||||

| Fitness of Destination | FD01 | 0.855 | 0.92 | 0.70 | 0.919 |

| FD02 | 0.776 | ||||

| FD03 | 0.886 | ||||

| FD04 | 0.814 | ||||

| FD05 | 0.836 | ||||

| Perceived Value | PV01 | 0.914 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.923 |

| PV02 | 0.954 | ||||

| PV03 | 0.822 | ||||

| Desire to Travel | DT01 | 0.889 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.865 |

| DT02 | 0.859 |

| Content | Fitness of Destination | Perceived Value | Desire to Travel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | (0.831) | |||

| Fitness of Destination | 0.800 *** | (0.837) | ||

| Perceived Value | 0.634 *** | 0.682 *** | (0.900) | |

| Desire to Travel | 0.656 *** | 0.652 *** | 0.240 *** | (0.872) |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Content (CT) → Fitness of Destination (FD) | 0.900 | 0.56 | 16.673 | *** |

| H2: Content (CT) → Perceived Value (PV) | 0.107 | 0.153 | 0.791 | 0.429 |

| H3: Content (CT) → Desire to Travel (DT) | 0.405 | 0.150 | 2.905 | 0.004 ** |

| H4: Fitness of Destination (FD) → Perceived Value (PV) | 0.586 | 0.149 | 4.288 | *** |

| H5: Fitness of Destination (FD) → Desire to Travel (DT) | 0.559 | 0.155 | 3.717 | *** |

| H6: Perceived Value (PV) → Desire to Travel (DT) | −0.398 | 0.065 | −5.819 | *** |

| Effects | Estimate | p Value | BC 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content (CT) → Fitness of Destination (FD) → Perceived Value (PV) | |||

| Indirect effect | 0.527 | 0.001 ** | 0.311~0.772 |

| Direct effect | 0.107 | 0.541 | −0.155~0.348 |

| Total effect | 0.634 | 0.001 ** | 0.534~0.715 |

| Content (CT) → Fitness of Destination (FD) → Desire to Travel (DT) | |||

| Indirect effect | 0.250 | 0.089 | 0.013~0.491 |

| Direct effect | 0.405 | 0.019 * | 0.149~0.663 |

| Total effect | 0.656 | 0.001 ** | 0.577~0.728 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsai, C.-M.; Hsin, S.-P. The Influence of Influencer Marketing on the Consumers’ Desire to Travel in the Post-Pandemic Era: The Mediation Effect of Influencer Fitness of Destination. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014746

Tsai C-M, Hsin S-P. The Influence of Influencer Marketing on the Consumers’ Desire to Travel in the Post-Pandemic Era: The Mediation Effect of Influencer Fitness of Destination. Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014746

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsai, Chih-Ming, and Shih-Peng Hsin. 2023. "The Influence of Influencer Marketing on the Consumers’ Desire to Travel in the Post-Pandemic Era: The Mediation Effect of Influencer Fitness of Destination" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014746

APA StyleTsai, C.-M., & Hsin, S.-P. (2023). The Influence of Influencer Marketing on the Consumers’ Desire to Travel in the Post-Pandemic Era: The Mediation Effect of Influencer Fitness of Destination. Sustainability, 15(20), 14746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014746