Abstract

Climate change issues are gradually gaining attention in the planning field, especially in urban regions due to high vulnerability caused by their dense population and complex networks. Communities depend on local policy tools to identify threats, determine goals, and implement strategies. Consequently, many cities around the world have developed climate adaptation plans to reduce climate impacts in the past decades. This study applied a plan evaluation framework to analyze and compare the plan quality of the latest climate adaptation plan in Taipei and Boston. The study examines key elements of adaptation plans to reveal strengths and weaknesses, and to compare and learn between adaptation plans internationally. Findings suggest that the framework provides comparable measures and analysis across international settings. We find that Taipei has a weak fact base and fails to address uncertainty, which importance in adaptation plans has been acknowledged only recently. We also identified shortfalls in public participation and implementation items in both cities. The study concludes by discussing results and giving recommendations to inform more effective approaches as practitioners develop or reevaluate climate adaptation plans.

1. Introduction

Climate change has been gaining attention in the past four decades [1] as climate-induced events severely impact the livelihood and well-being of human society [2]. Focusing on the present and potential interaction between human society and impacts brought by climate change, vulnerability is growing and will continue to grow due to society’s inability to adapt to the dynamic environment. Accumulating evidence recognizes that human influence is likely the dominant reason for Earth’s rapid warming [3,4,5]. Consequently, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) formed in 1988, introducing mitigation measures through greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction at the international level in the late 20th century [6].

Attention shifted to climate adaptation due to the realization that climate change impacts are unavoidable despite mitigation efforts [5,7,8], increased evidence that the human-induced climate change is impacting physical, biological, and social systems [2,3,4], and awareness of the existing physical and social environment’s lack of capacity to cope with the uncertainty of climate change impacts [9]. Threats from extreme weather events increase as vulnerabilities grow, especially in urban areas, where population are denser. In response, local entities have begun to incorporate climate adaptation strategies in planning and policy-making [10,11]. The interconnectedness and inseparable nature of urban systems calls for planning efforts that could address cities as a whole [12], and local planning holds the tools and power to stimulate and build adaptive capacity [7,13,14,15,16,17]. Thus, cities have started to establish plans and policies dedicated to the adaptation of climate change to reduce and prepare for climate impacts in the future.

However, local climate adaptation plans are largely under-developed [6] due to barriers such as insufficient resources or skills [18], inability to frame the issue, failing to identify actions, or lack of implementation [19,20]. Climate adaptation plans could become irrelevant and unused if future conditions diverge from projections, if strategies do not effectively address issues, or if no management process is established. To address this failure to implement climate adaptation plans, planners need to inspect the shortcomings of existing plans as well as formulate a systematic framework that guides plan-making. Thus, existing studies using plan quality evaluation for climate adaptation plans are introduced in the United States [21] and other developed countries [6]. Studies found that higher quality plans are more effective and better at addressing and achieving goals [22]. Existing studies on plan quality evaluation for climate adaptation plans are scarce and have never been done in Taiwan. Additionally, there is little research on plan evaluation that compares climate adaptation plans internationally. Therefore, this study aims to fill this research gap by providing a framework that can compare adaptation plans between Taiwan and the United States, in addition to analyzing Taiwan’s adaptation plan.

In this study, we utilize a climate adaptation plan quality evaluation framework to analyze and compare climate adaptation plans in Taipei, Taiwan and Boston, United States. The evaluation identifies critical elements in climate adaptations plans to provide recommendations and guidance on the improvement of adaptation planning in the two cities. We aim to answer the questions: (1) What are the strengths and weaknesses of climate adaptation plans in Taipei and Boston? (2) How do climate adaptation plans vary between Taipei and Boston? and (3) What are the opportunities to overcome barriers and improve future plans?

This study is the first to utilize the plan evaluation framework to compare the quality of climate adaptation plans internationally. The framework can be applied to countries with presidential and semi-presidential republic governance systems, which provides a quantifiable, systematic method across space and time. Applying the plan evaluation method, we assess whether plans match with criteria of best practices, identifying a plan’s strengths and weaknesses and allowing systematic plan comparison across time and space. Taking a closer look at the political and social environment of both countries and examining possible effects on the quality of CAPs, this study reveals barriers and policy implications on how local planners and local entities could improve on future climate adaptation planning. Results indicate that Boston and Taipei plans are weaker in providing details on public participation, management, and uncertainty. Further in the discussion, we dig deeper into how the cities’ current progress of the adaptation plans, the political environment, and past experience could affect their plan quality. Finally, the conclusion recognizes limitations and provides direction for future studies.

2. Literature Review: Climate Adaptation Planning and Plan Quality Evaluation

Climate adaptation can be traced back to the roots of adaptation to Darwin’s evolution theory and the development of human societies, as humans continuously adjust to changes their surroundings to increase positive impacts and decrease negative impacts received from the environment [12,23]. However, this biological adaptation differs from climate change adaptation through the level of planning, consciousness of adaptive actions, and time compression [12,24]. Adaptation to climate change focuses on building society’s adaptive capacity to adjust to climate change impacts specifically, proactively adapting to potential changes instead of reacting to environmental changes [12]. According to IPCC, adaptation to climate change is adjusting to any potential impacts, opportunities, and consequences due to change in climate. Literature presents different concepts and definitions to climate change adaptation, such as system adjustments in response to climate impacts [25,26] and vulnerability reduction [27]. These definitions often emphasize collective change in the entire system, rather than solely reducing impacts on part of the society or environment [12,28,29]. Additionally, short-term actions, such as engineering solutions that targets the reduction of impacts, are shown to be inflexible and even increase risks [30]. The variety in hazard type, climate predictability, social-political elements, and environmental conditions suggest the complexity of adaptation assessment, planning, policy-making, and implementation [18]. Many existing disciplines, including agriculture [31], disaster risk management, capital investment planning, engineering, and disaster risk management [32], have started to address climate change impacts by integrating adaptive actions into its decision-making process [33,34]. The extensiveness and interconnection of climate change effects on different aspects of the society increases the importance of coordination, collaboration, and mainstreaming of adaptation.

In response, local planning provides the need for including diverse strategies and collaborating among different disciplines. Local plans are a collection of policy tools that guide the development of communities, giving them the ability to significantly affect the community’s vulnerability to climate change impacts [35,36]. In recent years, the planning field has been developing plans with a focus on climate adaptation, demonstrating a systematic attention to climate change [11], with the expectation to limit negative impact under multiple projected future scenarios [20]. Adaptation planning started out at a national scale and has expanded to the local level in recent years due to an abundant of literature supporting that adaptation is local, recognizing local governments as the core and critical role in climate adaptation [7,10,14,16,17]. Climate impacts are experienced locally, and local government often has the legitimacy and policy tools to respond and manage while international- and national-level measures often fail to motivate local entities to respond to climate change [10]. Agrawal [13] concludes three ways the role of local institutions affects climate adaptation: (1) structuring strategies and responses to impacts, (2) shaping adaptation outcomes by mediating between individual and collective responses, and (3) facilitating adaptation through the access and delivery of resources. Further, literature accentuates the importance of the planning agencies and the roles of planners in climate adaptation planning [11,20,37,38]. Adaptation cannot solely rely on individual changes in the built environment but relies on regulations and policies to promote and enable these mechanisms for the long term [12]. Adaptation actions are dependent on the ability of organizations, government entities, individuals, communities, and such to act collectively, and this collective action is crucial to elevating adaptive capacity [39]. Consequently, local planning powers become the suitable tool to stimulate adaptation [10]. Planned adaptation assesses local context and information to prepare for potential future conditions through reviewing and updating current policies and practices [18]. This comprehensive process streamlines and includes an exhaustive fact base that informs the decision-making process of current conditions and various future projections and scenarios.

Taiwan’s climate adaptation planning efforts are fairly recent compared to the United States. Table 1 summarizes the timeline of Taiwan’s climate adaptation efforts.

Table 1.

Timeline of climate adaptation efforts in Taiwan.

The two main adaptation strategies in Taiwan are reactive and anticipatory adaptation [42]. Reactive strategies include groundwater conservation, soil retention, agriculture breed changes, emergency response improvement, seawall construction, etc. Anticipatory strategies include flood monitoring, research and development, early warning systems development, residential housing design, species monitoring, coastal management integration, coastal preservation policy-making, etc. Based on national strategies of the ASCCT, climate impacts are categorized into disasters, water resource, infrastructure, industry and energy supply, coast, agriculture and biodiversity, health, and land use. Lin [37] discussed the barriers to adaptation planning in Taiwan: (1) the lack of integration and coordination national and local level planning, (2) the inflexibility of early zoning impedes adaptation in spatial planning, (3) inconsistency of and failing to integrate strategies between sectors, and (4) adaptation is of low priority in policy implementation though the issue is viewed as high importance. While studies identify the overall barriers of adaptation planning in Taiwan, it does not give guidance on how these gaps could translate to the elements of the climate adaptation plans.

Climate adaptation planning in the United States is also in an early stage [38]. Climate adaptation emerged in the 2000s as a strategy in addition to climate mitigation. The first adaptation plan published in the United States was in 2007, and up to 2014, only 44 stand-alone, local adaptation plans were developed [20]. Climate adaptation plans in the United States are largely diversified. The decision and process of preparing the plan reflects local political will and leadership [14] since states do not mandate the development of a local climate adaptation plan. Adaptation strategies and actions are often traditional policies used in planning such as land use, transportation, building codes, etc. [14]. Studies have found that local climate adaptation plans are largely under-developed [6]. Since the United States do not mandate adaptation planning, barriers of developing an adaptation plan include insufficient resources, skills, or political will [18]. Moser & Ekstrom [19] identified three barriers that could emerge in the adaptation process: (1) understanding, which is the detection and framing of the problem, (2) planning, which involves the development of actions, and (3) management, the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation stages. In line with the barriers Moser identified in the adaptation planning process, plan quality evaluation methods are effective in assessing the weaknesses of climate adaptation plans in the United States. A plan quality evaluation study on 44 local climate adaptation plans found that climate adaptation plans in the United States elaborate more on its understanding and planning, or strategy development, but lacked information on how the policies and actions will be carried out and implemented [20]. Another weakness of the plans is failing to incorporate uncertainty, resulting in less flexibility of the plan.

To effectively identify barriers and guide improvement in adaptation planning, plan quality evaluation fills in the gap. Plan quality evaluation for adaptation is a recent development and previous studies mostly analyze adaptation plans using performance or logic framework methods [6,20,43]. Since adaptation is a dynamic social process that can be improved through continual learning [39], plan evaluation provides a systematic and comparable framework that allows us to understand the strengths, weaknesses, and identify barriers of a plan, to provide guidance on the improvement of adaptation plans. Alexander & Faludi observed that “if planning is to have any credibility as a discipline or a profession, evaluation criteria must enable a real judgment of planning effectiveness: good planning must be distinguishable from bad” [44]. While current studies focusing on Taiwan’s climate adaptation efforts uses logic framework [37,45] or policy argument methods [42] to identify barriers to planned climate adaptation and provide guidance on improvement, these methods do not allow comparison between plans. Plan evaluation is a systematic, quantitative, efficient method that defines plan quality, providing evidence of whether the plan reaches the desirable standards of quality [22,36]. Plan evaluation assesses whether plans match with agreed-on plan quality criteria, enabling the identification of a plan’s specific areas of strengths and weaknesses and, different from previous studies, allowing comparison of adaptation plans with other types of plans [20]. Using a uniform set of criteria to evaluate plan quality allows standard comparison of plans made across time and space. Baer [46] believes that formulating evaluation criteria is crucial to informing and creating better plan-making and studies have found that higher quality plans are more effective and better at addressing and achieving goals [22].

Past attempts to define the criteria of high-quality plans by identifying elements that are most likely to lead to implementation, which are those that most influence decisions of the local government [47]. Kaiser et al. [48] identified 3 basic characteristics to a high-quality plan: (1) a fact base that identifies existing conditions and issues of the community, (2) goals that addresses community demand, issues, and shared values, and (3) policies that guides the implementation of the goals. Consequently, Godschalk et al. [49] developed a more comprehensive list of plan quality criteria that includes implementation, monitoring, inter-organizational coordination, and public participation in addition to the 3 characteristics. Similarly, Berke & Godschalk [22] identified 7 internal characteristics of plan quality criteria including (1) vision, (2) goals, (3) fact base, (4) policies, (5) implementation, (6) monitoring and evaluation and, (7) internal consistency. From 1994 to 2012, more than 45 research papers utilized plan quality evaluation methods with a variety of principles and indicators [50]. Though plan quality evaluation methods have started gaining attention, few studies focus on the plan quality evaluation of climate adaptation plans. Woodruff & Stults established an evaluation framework that includes 7 principles, introducing the assessment of uncertainty in climate adaptation plans [20]. This was the first and only plan evaluation framework to date that evaluated uncertainty in planning. While Woodruff & Stults evaluated 44 adaptation plans in the United States, no studies evaluating the quality of climate adaptation plans have been done in Taiwan. This study aims to fill the gap by using plan evaluation methods to better examine the quality of Taiwan’s adaptation plan, evaluate the difference of plans between countries, and identify best practices to guide improvement.

3. Methodology: Plan Quality Evaluation

3.1. Selection of Cities

We perform a plan quality evaluation on two climate adaptation plans by selecting a city from the United States and another from Taiwan. The criteria for selecting climate adaptation plans are (1) local-scale plans at the city level, (2) stand-alone plans dedicated solely on climate change adaptation, (3) plans that have relatively or potentially good quality in the context of their country, and (4) the first climate adaptation plan produced by the city. Climate Ready Boston Adaptation Plan is Boston’s first stand-alone climate adaptation plan following the City’s 2007, 2011 update, and 2014 update of the Climate Action Plan [51]. Boston’s past efforts on climate change planning build up its potential to produce a high-quality adaptation plan [52]. Taipei City Climate Change Adaptation Plan is the first local climate adaptation plan in Taipei and Taiwan [53]. Taipei City, the capital of Taiwan, is the first local government to establish a local adaptation plan. Taipei City Climate Change Adaptation Plan is funded by Council for Economic Planning and Development, the national agency of Taiwan which is responsible for drafting plans for economic development. We argue that Taipei City has the largest capacity since it is the capital of Taiwan, making it the most resourceful and most populous city in Taiwan. We believe that this implies a greater potential in the development of a high-quality climate adaptation plan. Another criterion is the similarity of the two cities in their geographic location and climate impacts. Both Boston and Taipei are geographically located in coastal, flood-vulnerable areas. Boston has a population of 656,000 with an area of 89.63 square miles and Taipei has a population of 2,639,064 with an area of 104.56 square miles. Both cities are one of the most densely populated cities in their country, with 7319 and 25,239 people per square miles, respectively. The types of climate impacts identified are also similar as shown in Table 2, increasing comparability between the two cities.

Table 2.

Climate impacts identified in Taiwan and Boston adaptation plans.

3.2. Plan Evaulation Framework

Using the plan evaluation framework, we scored Taipei and Boston’s climate adaptation plan. The framework includes 6 plan quality principles that are commonly used in past studies—(1) purpose, goals, and objectives provides a vision and guidance of the community’s desired future; (2) public participation describes the techniques and involvement of stakeholders; (3) coordination describes the engagement of various entities in the planning process; (4) fact base, informs existing conditions, data, and projected risks; (5) strategies establishes and prioritizes actions for adaptation; and (6) implementation and monitoring ensures methods are in place to carry out the plan and evaluate progress. In addition to the 6 principles, uncertainty is added as a principle to address the uncertainties in climate change projections [20]. Each principle includes several indicators to assess the extent to which adaptation plans address it. There are a total of 119 indicators scored in this study, including 6 indicators for purpose, goals, and objectives, 9 indicators for public participation, 8 indicators for coordination, 44 indicators for fact base, 23 indicators for strategies, 16 indicators for implementation and monitoring, and 13 indicators for uncertainty.

This plan evaluation framework is based on an adaptation of the 7 plan evaluation principles for climate adaptation plans within the U.S as described in Woodruff & Stults’ study [20]. To ensure applicability of the framework, each indicator is carefully compared against the political organization and cultural background of Taiwan. As a result, an indicator of the Coordination principle—“coordination of state agencies”, is deleted from the evaluation criteria because Taiwan does not have the state level of government and Taipei a Yuan-controlled municipality, meaning that it is under direct control of the central government. Similarly, “federal agencies” are reframed as highest level of government, or central government. In addition, an indicator of the Fact Base principle that evaluates whether the plan illustrates a city’s experience of “presidentially declared disaster”, is reframed as “declared disaster” since Taiwan’s disasters are declared according to regulations of the Central Emergency Operation Center instead of by the president. As such, the framework can be utilized in presidential and semi-presidential republic governance systems.

The main methodological limitation of this framework is evaluating implementation success and possible modifications after plan adoption. While the framework identifies the importance of including monitoring requirements, evaluations metrics and methods, and updating plans, it does not discuss the actual changes, failures, and success during practice. The discussion briefly mentions current progress of the adaptation plans; however, future studies could fill the gap by tracking progress as the plans are implemented to their horizon.

3.3. Data Analysis

To perform the plan evaluation, a rater goes through each indicator, evaluating the plan to identify whether it includes the elements that the indicator describes. Each indicator is coded ‘0’ or ‘1’ to represent an absence or presence of the criteria within the plan. ‘0’ means that the plan does not include the indicator and ‘1’ means that the plan includes the indicator. After all indicators are coded, the indicators that are coded ‘1’ are added and then calculated as a percentage of the total score. To ensure the reliability of the data, the plans are scored by two researchers independently [36,54]. After coding each indicator independently, the coders come together to discuss and agree upon a score. The scores coded by these two researchers have an intercoder reliability of a 98.3% agreement. Each of the 7 principles identifies sections of weakness and strengths as well as compare between the two cities. We analyze using descriptive statistics and qualitative reasoning of detailed criterion in the next section. Table 3 demonstrates examples of the coding process.

Table 3.

Example of coding indicators for climate adaptation plans.

4. Results

4.1. Plan Quality between Taipei and Boston

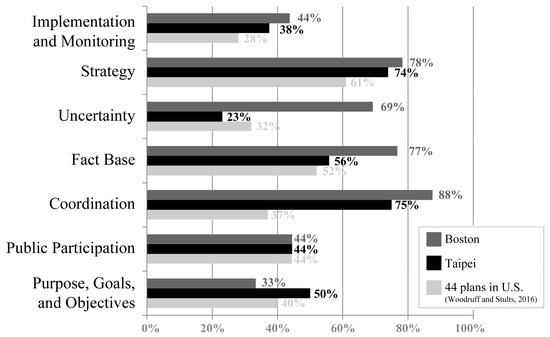

Results from the plan evaluation framework indicate that Boston’s climate adaptation plan has higher quality than Taipei’s climate adaptation plan. Boston scored 62% and Taipei scored 51%. Closer inspecting the scores of the 7 principles, Boston and Taipei has similar variance, with Boston’s score range of 54% and standard deviation of 0.21 and Taipei’s score range of 51% and a 0.19 standard deviation. As shown in Figure 1, Climate Ready Boston Adaptation Plan has a substantially higher score in coordination, fact base, and uncertainty. Scores for public participation, strategy, and implementation and monitoring are similar, and Taipei City Climate Change Adaptation Plan has a higher score in articulating the plan’s purpose, goals, and objectives. The section with the lowest score of the Taipei’s climate adaptation plan is uncertainty (23%), implementation and monitoring (38%), and public participation (44%). Other sections scored higher than 50% and the strategy section has the highest score of 74%. Boston’s lowest scores lie in its articulation of purpose, goals and objectives (33%), public participation (44%), and implementation and monitoring (44%). Other sections have high scores, with coordination as the highest-scored principle (88%).

Figure 1.

Comparison of Boston and Taipei’s scores [20].

Taipei is better at articulating its purpose, goals, and objectives compared to Boston. Taipei has 3 of the indicators out of 6 (50%) and Boston has 2 (33%). The difference is that Taipei clearly states its goals, while Boston steps straight from the City’s vision to its strategies.

4.2. Barriers to Innovation

Innovation refers to the “intentional and proactive process that involves the generation, practical adoption, and spread of new and creative ideas which aim to produce a qualitative change in a specific context” [55]. Both Boston and Taipei have high coordination scores, which allows new cooperative knowledge, information, and mobility in capacity and resources [56]. On the contrary, the low scores in the public participation section become barriers to inclusive planning, impeding the generation of new ideas and local learning [56]. Lastly, Taipei has a low fact base score, failing to include information on adaptive capacity and details on present status, which hinders the development of strategies reflecting local circumstances [14].

In the coordination section, Taipei scored 75% and Boston scored 88%. Boston does not include federal agencies while Taipei does not include nonprofits and neighboring jurisdictions in the planning process. Taipei’s working group that is responsible for pushing forward the planning process consists of researchers and specialists, government entities representation, and the vice-mayor. Forums include government agencies as representatives of each discipline. The businesses involved in the plan-making process are related to the infrastructure and public services of the city, such as Taiwan Power Company and Great Taipei Gas Cooperation. Taipei’s plan has a detailed description of the involvement and coordination process of these agencies and organization. Compared to Boston, Taipei failed to include neighboring jurisdictions and nonprofits in its plan; however, Taipei’s plan recognizes that neighboring jurisdictions should be included in future plan updates. Not including nonprofits compound with little public participation, resulting policies and actions could be counterproductive or even hurt the rights of marginalized groups and vulnerable populations. On the other hand, Boston does not include higher entities in the plan-making process, thus its plan failed to incorporate and utilize possible resources and knowledge provided by federal agencies.

Both Boston and Taipei scored 44% on public participation and both plans include the same indicators. Taipei’s plan does not include public engagement in the planning process. Boston’s plan does include workshops, but it was only mentioned in a sentence and without the process or documentation of how the plan integrates public feedback. Though both plans lack public participation, their strategies recognize the importance of engaging the public, and the strategies include actions for the public at a community level. Their approach to public engagement is very different. Strategies in Taipei’s plan aims to educate the public to avoid and react to hazards, while Boston’s strategies encourage community members to provide insight in addition to education. Boston’s approach can establish a two-way communication path between the public and plan-makers, while Taipei modes a top-down approach.

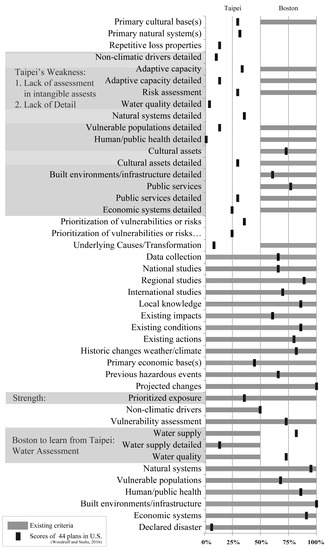

Overall, Taipei’s fact base covers a comprehensive assessment of physical infrastructure, though it has is less detailed and evidently lacks the assessment of the software, or more intangible items, of the city. Figure 2 shows the comparison between Taipei and Boston’s fact base. One of the strengths of Taipei’s fact base is the prioritization of exposure. A working group identifies three key areas before analyzing vulnerability. This is helpful for identifying areas that are most at stake so more efforts and resources can be concentrated on it. Another strength is the assessment of water supply and water quality, which Boston lacks. Taipei’s plan does not address the adaptive capacity of the community (D21), identify cultural assets (D34), and public services (D38). Though the plan recognizes Taipei’s lack of adaptive capacity, it does not elaborate on the extent or areas with gaps. Lack of identification of cultural assets could be due to society differences, since culture and recreation is often thought of as a luxury item instead of a necessity. Nevertheless, locating understanding the community’s ability to respond to future impacts, etc., are all information that is helpful in fostering new ideas during the decision-making process.

Figure 2.

Fact base comparison between Taipei and Boston [20].

4.3. Incorporation of Uncertainty

Taipei has a weak uncertainty section, including only 3 of the 13 indicators (23%). Boston, on the other hand, has a high score of 69%, missing 4 indicators related to the provision of details for strategies. Uncertainty is a weakness in many U.S. adaptation plans, with an average of 32% in the 44 plans in the Woodruff & Stults study [20]. Taipei’s plan acknowledges that there are uncertainties in future scenarios but does not give information on multiple scenarios. The term “no-regret” is only mentioned once in the introduction and does not contribute to plan. Taipei does not include indicators, including multiple scenarios, robust and flexible strategies, and multiple time frames. Overall, it is clear that uncertainty is not considered in Taipei’s plan and Taipei failed to integrate uncertainty in its fact base, strategies, and implementation. It is important that uncertainty is considered throughout the plan to make an effective and adaptive plan [21].

4.4. Weak Management of Adaptation Plans

Taipei and Boston scored high in strategy identification, 74% and 78%, respectively. Taipei has a wide variety of strategies, including strategies that focus on infrastructure, building codes, land use, research, and such. Two types of strategies that are not included are advocacy and policy and legislation. Since Taipei’s plan is under the framework of the national climate adaptation plan, advocacy such as encouraging higher entities might not be necessary. A weakness of Taipei’s plan is that it neither identifies the cost of each strategy nor the cost of inaction of the strategies. Estimating the cost of actions provides motivation to implement the plan. In short, Taipei has a variety of strategies but lacks elements that help the strategies translate into implementation.

Implementation and monitoring is a weakness in many adaptation plans, and unsurprisingly, both Taipei and Boston’s plan also lack in this section. Taipei scored 38% and Boston scored 44%, both missing similar criteria. Both plans include mainstreaming, implementation responsibilities and possible barriers to implementation and fail to identify funding sources, plan updates, monitoring, reporting, and evaluation methods. However, Boston has a separate funding plan. Additionally, Taipei does not include a timetable for implementation.

5. Discussion

The plan evaluation framework proves to be applicable to cities in Taiwan and the United States. The framework provides guidance on plan-making best practices and identifies insufficient planning efforts to establish an effective and implementable adaptation plan. Findings suggest that Boston has a higher quality climate adaptation plan than Taipei. This is a foreseen result since Boston has adopted several climate action plans before this first adaptation plan. From the results, Table 4 compares the Taipei and Boston’s plans under the categories (1) barriers to innovation, (2) incorporation of uncertainty, (3) management of adaptation plans, and (4) plan documentation.

Table 4.

Comparison between Taipei and Boston’s adaptation plans.

Since Taipei’s climate adaptation plan focuses on a formulated process under the framework of the ASCCT, every step of the planning process is clearly documented and streamlined. From Taipei’s high score in articulating purpose, goals, and objectives, and overall average scores of each principle, we can see the stiff structure of the plan. While a clear guidance for planning is often helpful for building a comprehensive plan, it could also create issues due to its rigidness [57] such as the limitation of innovative strategies due to standardization [14]. Since the planning framework is set by the nation and the production of the plan mandated, it is harder to think out of the box. This could also cause little innovation in the fact base, which only includes basic background, projections, and physical vulnerabilities, and is missing assessment of intangible concepts or fails to use methods, such as overlaying data, to gain new perspective. The absence of community motivation can also cause possible barriers to implementation of the plan [58,59]. Further, in combination with lack of public participation and consideration of uncertainty, Taipei developed few innovative strategies. Though some strategies and actions are directed to the public, such as education on climate change and response, communication pathways seem one-sided with the plan providing information to the public. Best practice recognizes the importance of integrating comments and feedback from citizens, not only to make innovative plans but also increase feasibility through the support and commitment of the community. Since the formation of Taipei’s plan is from the requirement of a higher government agency, it is easy to fall into the trap of doing just enough instead of aiming for a higher goal. However, while Bunnell & Jepson [57] found that mandated plans could be more rigid, they did not find evidence of mandates significantly affecting the quality of plans. Berke & French [47] found that mandates measurably affect plans and suggested that plan quality is largely affected by the context of the mandate itself. In the case of Taipei’s plan, updates could become more informed and to the ground by planning the responsibilities of reporting, monitoring, and evaluating progress. This can stop the vicious cycle of making plans for the sake of making plans.

While Taipei’s adaptation plan is not as mature as Boston’s plan, is complete and streamlined. Taipei’s adaptation plan calls for the greatest improvement in the “management” phase and is the most developed in its “planning” phase [19]. “Planning” indicates the development of strategies and the decision-making process, which is very clear in Taipei’s plan. “Management” includes implementation, monitoring, and evaluation, which Taipei lacks. Since jurisdictions in Taiwan have similar climate impacts as Taipei, and plans regularly borrow from one another, we argue that this result could be expanded to provide suggestions and policy implications to other climate adaptation plans in Taiwan.

The largest performance difference of the 7 principles is uncertainty. While “no-regret” and “uncertainty” are articulated in Taipei’s plan, there is no substantial information that elaborates on the data, methods, or process taken to understand or integrate uncertainty in the plan. Uncertainty should be considered throughout the planning process to ensure that the plan is effective and adaptive in various future scenarios. Recognition of uncertainty is a good first step. Methods of integrating uncertainty can be drawn from the indicators such as adding multiple scenarios in the fact base (E3), adding no-regret (E12) and robust strategies (E10), and developing strategies for both short- and long-term (E7). Boston gives a good example on assessing multiple scenarios by using high, medium, and low emission scenarios for its projections. This allows the development of flexibility and adaptability strategies, such as robust initiatives to build high ground-floor ceilings in buildings that could be raised as sea level rise over time.

Boston and Taipei perform best in engaging multiple agencies in the planning process and integrating extensive strategies. In the plan Taipei provided detailed documentation of the plan-making process, including the time, chair, representatives, context, such as consensus on decision or recommendation, and responsibilities of every meeting and forum. We can see that Taipei coordinates and brings together sectors and agencies throughout the planning process. Boston also includes consulting companies, nonprofits, state and regional jurisdictions, the University of Massachusetts, and city departments in the planning process. Strong strategy identification is common in climate adaptation plans. However, while strategies can be comprehensive and address all identified climate impacts at different levels, translation of these actions to the ground is commonly a shortfall in plans.

The results reveal that Boston and Taipei both lack public participation and implementation and monitoring elements. Climate adaptation plans in the United States commonly perform weaker in integrating implementation and monitoring elements [20]. Public participation and integration of community input are important, especially plans that require every sector of the community to take action. Communities are more likely to stand behind and implement actions that incorporate their thoughts and efforts. Boston included local involvement in the decision-making process but did not describe the method of engagement nor detail the input received. Thus, we are unable to see how public input is incorporated into the plan. Regarding implementation and monitoring, missing evaluation methods and monitoring responsibility could lead to barriers such as misperception of capacity, resources, and political and social structure [19], which could result in a plan that cannot be implemented thoroughly. The lack of monitoring can undermine success and misguide decision-makers [19].

To connect discussions with current plan implementation progress of both cities, we look at the City of Boston’s Climate Action Fiscal Year 2021 Report and Taipei’s 2021 Taipei City Voluntary Local Review. Boston released a progress report to promote transparency and track progress of all 11 strategies and 39 initiatives outlined in its climate adaptation plan. The 2021 Report categorizes the status of each initiative as not started, in progress, delayed, ongoing, or complete, and provides a detailed description of its progress [60]. While Boston does not include evaluation methods or monitoring responsibility in its adaptation plan, the annual report provides effective tracking of implementation progression. In addition, while funding sources are not detailed in Boston’s climate adaptation plan, Boston developed a stand-alone funding plan for initiatives identified in the adaptation plan. Overall, even without including all implementation and monitoring indicators within its plan, Boston is smoothly carrying out its plan through reporting progress. On the other hand, Taipei has not been acting on its climate adaptation plan according to the city’s 2021 Review report. Taipei’s Review report is dedicated to the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established in 2016 rather than the climate adaptation plan. According to the 2021 Review, the climate adaptation plan is a foundation to adaptation actions, however, the SDGs that were developed later to reorganize and provide guidance on sustainability actions [61]. To prevent failure of implementing plans in the future, Taipei can incorporate a timeline for actions, funding sources, and evaluation methods to ensure that the adaptation plan can be clearly followed.

6. Conclusions

This study recognizes the rising attention on climate change adaptation, particularly the recent development of climate adaptation plans in response to the inevitable future climate impacts and aims to evaluate the quality of adaptation plans for improvements. It provides a framework to quantify and allow comparison between climate adaptation plans in different cities around the world. Despite political, cultural, and environmental disparities, the framework gives cities the ability to recognize a plan’s strengths and shortfalls, which then provides guidance for improvement. Comparison between plans allows a city to reference from successful plans.

From evaluating adaptation plans from two countries, we recognize several opportunities to overcome barriers and improve future plan updates. First, cities should engage the public and involve multiple entities in the plan-making process. Representative stakeholders, planning committees, nonprofits, government agencies, neighboring jurisdictions, and private organizations should be included in the plan-making process. Public participation includes involvement during both the plan preparation and planning process, and participation techniques should be established to ensure effective and meaningful engagement. This is especially crucial to Taipei since the development of innovative policies requires the perspectives of diverse groups [14]. Next, plans should incorporate uncertainty in their adaptation strategies. In addressing uncertainty, Taipei should consider multiple future scenarios and develop strategies that are robust or low-regret to fill the gap of the inaccuracy of projections. Even though Boston’s plan has a higher score in uncertainty, the plan can still be improved by identifying actions as no-regret, low-regret, and robust. Uncertainty is an inevitable element, especially in adaptation planning since it allows adjustment to help plans remain relevant and effective in the different scenarios [43]. Lastly, a detailed implementation plan could be helpful for carrying out the plan. Most importantly, taking action and monitoring progress after plan adoption is crucial. Consequently, planners and planning departments play a crucial role to facilitate, coordinate, and streamline between groups and agencies to work side by side on taking actions.

From these discussions, we identify 3 main policy implications for cities looking to improve their climate adaption plans: (1) to strengthen the engagement process, planners should reach out to the public as soon as the city decides to plan for adaptation, create a platform to collect public feedback during the planning process, and integrate the comments into the plan; (2) to increase flexibility and adaptiveness of the plan, the task force that provides information for the fact base should include multiple projections and scenarios so robust strategies could be developed; (3) to ensure translation of the plan to the ground, planners should establish metrics and specific timelines for each strategy or action to evaluate and monitor the progress towards goals and objectives.

To conclude, future research could focus on the reasons behind strategies that are implemented and barriers that impede those that are not implemented. This would give an in-depth understanding of how planners should approach and develop strategies in climate adaptation plans, thus enhancing adaptation efforts. This would also provide insight on how the plan evaluation method correlates to the translation of climate adaptation plans to the ground. In addition, to further understand the discrepancy between adaptation planning and implementation in Taiwan, future studies should also extend the evaluation of plans to all local climate adaptation plans in Taiwan as well as conduct interviews with planning agencies. This would provide a more exhaustive overview of Taiwan’s plan quality holistically to avoid bias when guiding improvement. Additional research could also be directed in understanding the context of Taiwan’s national mandate to identify barriers due to political, cultural, and social issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T.; methodology, S.T.; validation, S.Y.; formal analysis, S.Y.; resources, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.; visualization, S.T.; supervision, S.Y.; project administration, S.T.; funding acquisition, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to show their gratitude to Sierra Woodruff for insights and comments on the early stages of research conceptualization and her previous work on the development of the plan quality evaluation framework used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Moser, S.C. Communicating climate change: History, challenges, process and future directions. WIREs Clim. Change 2010, 1, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Casassa, G.; Karoly, D.J.; Imeson, A.; Liu, C.; Menzel, A.; Rawlins, S.; Root, T.L.; Seguin, B.; Tryjanowski, P. Assessment of observed changes and responses in natural and managed systems. In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Parry, M., Canziani, O., Palutikof, J., van der Linden, P., Hanson, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 79–131. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ar4-wg2-chapter1-1.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Hegerl, G.C.; Zwiers, F.W.; Braconnot, P.; Gillett, N.P.; Luo, Y.; Marengo Orsini, J.A.; Nicholls, N.; Penner, J.E.; Stott, P.A. Understanding and Attributing Climate Change. In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Solomon, S., Qin, M.D., Manning, Z., Chen, M., Marquis, K.B., Averyt, M., Tignor, M., Miller, H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA,, 2007; pp. 665–745. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ar4-wg1-chapter9-1.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/ (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- UNFCCC. Fact Sheet: Climate Change Science-the Status of Climate Change Science Today. Paper Presented at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2011. Available online: https://unfccc.int/files/press/backgrounders/application/pdf/press_factsh_science.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Preston, B.L.; Westaway, R.M.; Yuen, E.J. Climate adaptation planning in practice: An evaluation of adaptation plans from three developed nations. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2011, 16, 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füssel, H.-M.; Klein, R.J.T. Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments: An Evolution of Conceptual Thinking. Clim. Change 2006, 75, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehl, G.A.; Stocker, T.F.; Collins, W.D.; Friedlingstein, P.; Gaye, A.T.; Gregory, J.M.; Kitoh, A.; Knutti, R.; Murphy, J.M.; Noda, A.; et al. Global Climate Projections. In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K., Tignor, M., Miller, H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA,, 2007; pp. 749–845. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ar4-wg1-chapter10-1.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Hallegatte, S. Strategies to adapt to an uncertain climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measham, T.G.; Preston, B.; Smith, T.; Brooke, C.; Gorddard, R.; Withycombe, G.; Morrison, C. Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: Barriers and challenges. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 2011, 16, 889–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.M. State and Municipal Climate Change Plans: The First Generation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2008, 74, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, E.L.F. Climate change adaptation and development: Exploring the linkages. Tyndall Cent. Clim. Change Res. Work. Pap. 2007, 107, 13. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228391167_Climate_change_adaptation_and_development_Exploring_the_linkages (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Agrawal, A. The Role of Local Institutions in Adaptation to Climate Change; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28274 (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Bassett, E.; Shandas, V. Innovation and Climate Action Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Kates, J.; Malecha, M.; Masterson, J.; Shea, P.; Yu, S. Using a resilience scorecard to improve local planning for vulnerability to hazards and climate change: An application in two cities. Cities 2021, 119, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, L.O.; Bang, G.; Eriksen, S.; Vevatne, J. Institutional adaptation to climate change: Flood responses at the municipal level in Norway. Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.F.; Preston, B.; Brooke, C.; Gorddard, R.; Abbs, D.; McInnes, K.; Withycombe, G.; Morrison, C.; Beveridge, B.; Measham, T.G. Managing coastal vulnerability: New solutions for local government. In Integrated Coastal Zone Management; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Füssel, H.-M. Adaptation planning for climate change: Concepts, assessment approaches, and key lessons. Sustain. Sci. 2007, 2, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; Ekstrom, J.A. A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22026–22031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, S.C.; Stults, M. Numerous strategies but limited implementation guidance in US local adaptation plans. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, S.C. Planning for an unknowable future: Uncertainty in climate change adaptation planning. Clim. Change 2016, 139, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Berke, P.; Godschalk, D.R. Searching for the Good Plan. J. Plan. Lit. 2009, 23, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithers, J.; Smit, B. Human adaptation to climatic variability and change. Glob. Environ. Change 1997, 7, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olshansky, R.B.; Hopkins, L.D.; Johnson, L.A. Disaster and Recovery: Processes Compressed in Time. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2012, 13, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, N. Vulnerability, Risk and Adaptation: A Conceptual Framework. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research. Working Paper No. 38. University of East Anglia. 2003. Available online: https://www.climatelearningplatform.org/sites/default/files/resources/Brooks_2003_TynWP38.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Smith, B.; Burton, I.; Klein, R.J.; Wandel, J. An Anatomy of Adaptation to Climate Change and Variability. Clim. Change 2000, 45, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Wandel, J. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Nightingale, A.J.; Eakin, H. Reframing adaptation: The political nature of climate change adaptation. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA,, 2014; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/ (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Lawrence, J.; Sullivan, F.; Lash, A.; Ide, G.; Cameron, C.; McGlinchey, L. Adapting to changing climate risk by local government in New Zealand: Institutional practice barriers and enablers. Local Environ. 2013, 20, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Burke, M.B.; Tebaldi, C.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L. Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation Needs for Food Security in 2030. Science 2008, 319, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, M.; Tangney, P.; Reis, K.; Grant-Smith, D.; Heazle, M.; Bosomworth, K.; Burton, P. Towards networked governance: Improving interagency communication and collaboration for disaster risk management and climate change adaptation in Australia. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 58, 757–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, L.M.; Anderson, C.J.; Samaras, C. Framework for Incorporating Downscaled Climate Output into Existing Engineering Methods: Application to Precipitation Frequency Curves. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2017, 23, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, R.; Arnold, J.; Pulwarty, R.; Lempert, R.; Gordon, K.; Greig, K.; Hoffman, C.H.; Sands, D.; Werrell, C.; Lazarus, M.A. Reducing Risks Through Adaptation Actions. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II; Reidmiller, D.R., Avery, C., Easterling, D., Kunkel, K., Lewis, K., Maycock, T., Stewart, B., Eds.; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1309–1345. Available online: https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/28/ (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Berke, P.; Yu, S.; Malecha, M.; Cooper, J. Plans that Disrupt Development: Equity Policies and Social Vulnerability in Six Coastal Cities. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 13, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Brand, A.D.; Berke, P. Making Room for the River. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2020, 86, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T. The Gap of Climate Adaptation Development of the Spatial Planning System in Taiwan: How the Multilevel Planning Agencies Respond to Climate Risk. In Book of Proceedings: AESOP 29th Annual Congress 2015 “Definite Space-Fuzzy Responsibility”; Czech Technical University: Prague, Czech Republic, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lyles, W.; Berke, P.; Overstreet, K.H. Where to begin municipal climate adaptation planning? Evaluating two local choices. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 61, 1994–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 79, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for Economic Planning and Development. Adaptation Strategy to Climate Change in Taiwan. 2012. Available online: https://ws.ndc.gov.tw/Download.ashx?u=LzAwMS9hZG1pbmlzdHJhdG9yLzEwL3JlbGZpbGUvNTU2Ni83MDgwLzAwMTcxMjRfNi5wZGY%3d&n=5rCj5YCZ6K6K6YG3LeS4reaWh%2beJiHMyLnBkZg%3d%3d&icon=..pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- EPA. National Climate Change Adaptation Action Plan; Environmental Protection Administration, Executive: Yuan, Taiwan, 2019.

- Ke, W.-C. Argumentation on Adaptation Policy. J. Law Political Sci. 2018, 27, 41–85. Available online: https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=10232230-201807-201901020011-201901020011-41-85 (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Haasnoot, M.; Kwakkel, J.H.; Walker, W.E.; ter Maat, J. Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: A method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.R.; Faludi, A. Planning and plan implementation: Notes on evaluation criteria. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1989, 16, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.C. Exploring Community Adaptation Mechanism to Climate Change: A comparison between Taiwan and Vietnam. Taiwan J. Southeast Asian Stud. 2017, 12, 5–28. Available online: https://www.AiritiLibrary.com/Publication/Index/18115713-201704-201901220007-201901220007-5-28 (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Baer, W.C. General Plan Evaluation Criteria: An Approach to Making Better Plans. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1997, 63, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.R.; French, S.P. The Influence of State Planning Mandates on Local Plan Quality. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1994, 13, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, E.J.; Godschalk, D.R.; Chapin, F.S. Urban Land Use Planning; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1995; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Godschalk, D.; Beatley, T.; Berke, P.; Brower, D.; Kaiser, E.J. Natural Hazard Mitigation: Recasting Disaster Policy and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lyles, W.; Stevens, M. Plan Quality Evaluation 1994–2012: Growth and Contributions, Limitations, and New Directions. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2014, 34, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Boston. Climate Ready Boston Adaptation Plan. 2016. Available online: https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/embed/2/20161207_climate_ready_boston_digital2.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Vogel, J.; Carney, K.M.; Smith, J.B.; Herrick, C.; Stults, M.; O’Grady, M.; Juliana, A.S.; Hosterman, H.; Giangola, L. Climate Adaptation: The State of Practice in US Communities. Ontario Centre for Climate Impacts and Adaptation Resources. 2016. Available online: http://kresge.org/sites/default/files/library/climate-adaptation-the-state-of-practice-in-us-communities-full-report.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Council for Economic Planning and Development. Taipei City Climate Change Adaptation Plan. 2012. Available online: https://www-ws.gov.taipei/Download.ashx?u=LzAwMS9VcGxvYWQvMzYzL3JlbGZpbGUvMTY5NTIvMTEyMzczLzUzY2ViZTQ5LTZmYjQtNDAyZi04YTlhLTUyMDIxOTg2ZjA3MC5wZGY%3d&n=6Ie65YyX5biC5rCj5YCZ6K6K6YG36Kq%2f6YGp6KiI55WrLnBkZg%3d%3d&icon=..pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Stevens, M.R.; Lyles, W.; Berke, P.R. Measuring and Reporting Intercoder Reliability in Plan Quality Evaluation Research. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2014, 34, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Enhancing Collaborative Innovation in the Public Sector. Adm. Soc. 2011, 43, 842–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinson, R.; Chu, E. Learning pathways and the governance of innovations in urban climate change resilience and adaptation. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2018, 21, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnell, G.; Jepson, E.J., Jr. The Effect of Mandated Planning on Plan Quality. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2011, 77, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, W.; Berke, P.; Smith, G. Local plan implementation: Assessing conformance and influence of local plans in the United States. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2015, 43, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Malecha, M.; Berke, P. Examining factors influencing plan integration for community resilience in six US coastal cities using Hierarchical Linear Modeling. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 215, 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Boston. Climate Action Fiscal Year 2021 Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2021/10/FY21%20Boston%20Climate%20Action%20Report_3.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Taipei City. 2021 Taipei City Voluntary Local Review. 2021. Available online: https://www-ws.gov.taipei/Download.ashx?u=LzAwMS9VcGxvYWQvMzYzL3JlbGZpbGUvNDExMzIvODQ1ODY1Ni9lNGMzZTQwYi04NzcyLTQzNDItYTliZS0zZmIzNDdiNDcwODUucGRm&n=MjAyMeiHuuWMl%2bW4guiHqumhmOaqouimluWgseWRii5wZGY%3d&icon=..pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).