1. Introduction

In the context of non-financial reporting (NFR), the materiality concept acts as a filter that identifies what non-financial information (NFI) matters to the users of corporate non-financial reports (NFRs). Although this key role has led to a gradual increase in the importance of materiality since the beginning of this century, the concept remains somewhat ambiguous. Indeed, instead of a technical mechanism, it requires a social mechanism to be put into practice [

1]—one that takes into account the different ideas of social responsibility accepted pro tem [

2]. Assuming that information is material when its impact influences the decision-making processes of stakeholders, materiality takes a defined form when information, stakeholders, and impacts are defined [

3]. Thus, materiality is still an extremely controversial concept [

4], and is expected to remain so for a long time [

5].

The several international initiatives that in recent years have taken place in the crowded “contested arena” [

6] of the regulation of sustainability reporting differ from one another because they interpret the aforementioned three aspects (i.e., information, stakeholders, and impacts) differently, and not always clearly. These initiatives broadly divide into two main groups since they basically focus either on investors or on a wider pool of stakeholders. This polarization has contributed to splitting the current meanings of materiality into, respectively, “financial” and “impact” materiality. The European Union (EU), which belongs to the group that addresses the interests of a wide range of stakeholders, has even gone beyond the aforementioned dichotomy. Indeed, since 2014, the EU has increasingly adopted a third configuration of materiality named double materiality (DM). This materiality combines financial and impact materiality, which, in this way, become its “pillars”.

The sudden interest in DM expressed by the scientific community has given rise to various works debating the first critical issues encountered, whereas only a few empirical studies on its application and disclosure have emerged. The low level of empirical knowledge regarding how companies have concretely applied the concept in terms of measurement, locations, and methods of implementation gave rise to our research aim: to map pioneering experiences of DM in the NFRs of both European and non-European companies. To achieve this, an exploratory analysis was conducted on the NFRs of 58 sustainability-oriented companies operating in several industries and geographical areas over the period 2019–2021. Among the results that emerged, we found that few companies—not only European ones—have included DM in their NFRs, mainly in 2021. Moreover, we detected a wide range of varieties and distortions in the narratives that the NFRs have used to disclose DM. This foreshadows a worryingly fragmented landscape for what concerns the materiality analysis disclosures in the forthcoming NFRs.

In addressing the desire to intensify research on the concept of materiality and its application in NFR [

7], this article expands the literature on materiality disclosure in NFRs by specifically enriching the meager empirical research strand on DM. Specifically, this work contributes to the literature in three ways. First, we provide a pioneering survey that depicts the diffusion of the DM concept in the NFRs of companies operating in various countries and sectors in evolutionary perspective. Second, we offer an initial investigation of the different ways that both European and non-European companies have chosen to put DM into practice in their 2021 NFRs. In particular, 2021 was both the year in which there was greater evidence of DM emerging, and also the year of two relevant regulations involving materiality—namely, the EU’s proposal for a novel Directive on Corporate Sustainability Reporting [

8], and the new GRI 3 standard [

9]. Third, we investigate the first practices of DM implementation within the materiality assessment processes (MAPs) in both atomistic and summative perspectives, where the former perspective includes the examination of the relationships between DM and the GRI’s single materiality.

The article is structured as follows.

Section 2 outlines the EU’s path towards DM.

Section 3 presents the relevant literature, while

Section 4 describes the research design, materials and method.

Section 5 exposes the empirical results and is articulated in sub-sections according to the core phases of the analysis.

Section 6 discusses the main findings obtained.

Section 7 concludes with implications, limitations, and suggestions for further research.

2. Background: The European Union’s Path toward Double Materiality

The growing importance the materiality concept assumed in corporate NFI disclosure drove its increased centrality in NFR frameworks and the standards released, sometimes jointly, by various international bodies.

According to the number of stakeholders they address, these initiatives can be split into two groups [

7]. The first group includes the initiatives of the EU, GRI and the United Nations (UN). These initiatives are aimed at broad audiences of stakeholders, including investors. In materiality evaluations, they emphasize external impacts, such as those on the economy, environment and society. This materiality perspective is often called “impact materiality”. The second group includes the initiatives of the Financial Reporting Council (FRC), Taskforce of Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), and IFRS Foundation, that has recently incorporated the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), both recently merged into the Value Reporting Foundation (VFR) and the International Sustainability Standard Board (ISSB). These initiatives are mainly (or only) aimed at investors. In materiality evaluations, they emphasize the internal impacts—that is, those suffered by a company. This materiality perspective is often called “financial materiality”. Clearly, the aforementioned two groups of initiatives stem from the existence of two factions of actors who, in the area of sustainability reporting standard-setting, adopt methodological approaches to materiality different in substance and symbolism [

10].

Huston [

11] defines those initiatives that welcome a materiality assessment of NFI based on non-financial (i.e., external) impacts without delay as “radical”. Additionally, the author considers those initiatives to be “conservative”, including that of the ISSB, which, although sometimes acknowledging the future incorporation of non-financial impacts, adopts a (perhaps overly?) cautious and incremental attitude recognizing, at least in the present moment, only financial (i.e., internal) impacts. Moreover, observers are concerned about the ISSB’s initiative, since they presume it is motivated by the desire to defend its own standard-setting technical authority [

6]. Those observers fear that ISSB’s intervention in the sustainability reporting field will be able to drive migration from GRI’s to ISSB’s standards due to the “wrong signal” of the subordination of non-financial impacts to financial ones that its approach to materiality incorporates [

12].

The EU, while embracing the multi-stakeholder perspective, has embarked on a peculiar path consisting of a holistic fusion of the two materiality perspectives in the concept of DM, a concept which does not make the EU a competitor, but rather complementary, to other frameworks [

13]. The EU’s integration even goes beyond the idea of the complementary nature of the GRI and SASB Standards [

14]. This idea of considering the combined use of both series of Standards as a strong foundation for a comprehensive solution under the DM perspective [

15,

16] has led some authors to consider compliance with both Standards an empirical proxy of DM [

10].

In this particular context, the EU’s journey towards DM started with the so-called Non-Financial Disclosure Directive 2014/95/EU (NFDD), which amended the Accounting Directive 2013/34/EU as regards non-financial and diversity information provided by certain large companies and groups. Not without ambiguity [

2,

17], NFDD only substantially embraces the principle of materiality [

18] and broadens the traditional materiality evaluation of NFI based on financial impacts. The traditional assessment based on factors such as company performance, results and business situation is enlarged by including the external impact of the business activity. The non-binding guidelines of 2017, where materiality formally reappears, underline the external impact novelty [

19]. Such guidelines stress also means that, for the purposes of the materiality assessment, external impacts can be positive or adverse, as well as considered in a clear and balanced way. The 2019 update to the guidelines [

20], which focused on climate change, expressly uses the expression DM for the first time, a concept that the EU also uses in the context of sustainable finance regulation, specifically in the discipline on sustainability disclosures in the financial services sector (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088). According to the 2019 guidelines, NFDD’s materiality perspective covers both financial materiality, and environmental and social materiality. Specifically, financial materiality “is used here in the broad sense of affecting the value of the company, not just in the sense of affecting financial measure recognized in the financial statements” [

20]. Hence, the “financial” pillar is summarized in the orientation towards business value creation, an aspect that typically interests investors, while the “impact” pillar is defined as social and environmental materiality, a perspective that investors are increasingly interested in. Moreover, the 2019 guidelines offer a clarifying visual that, although focused on climate change NFI, highlights what the two opposite impact perspectives of materiality assessment mean. It also clarifies that the impacts that are socially and environmentally material could become financially material (

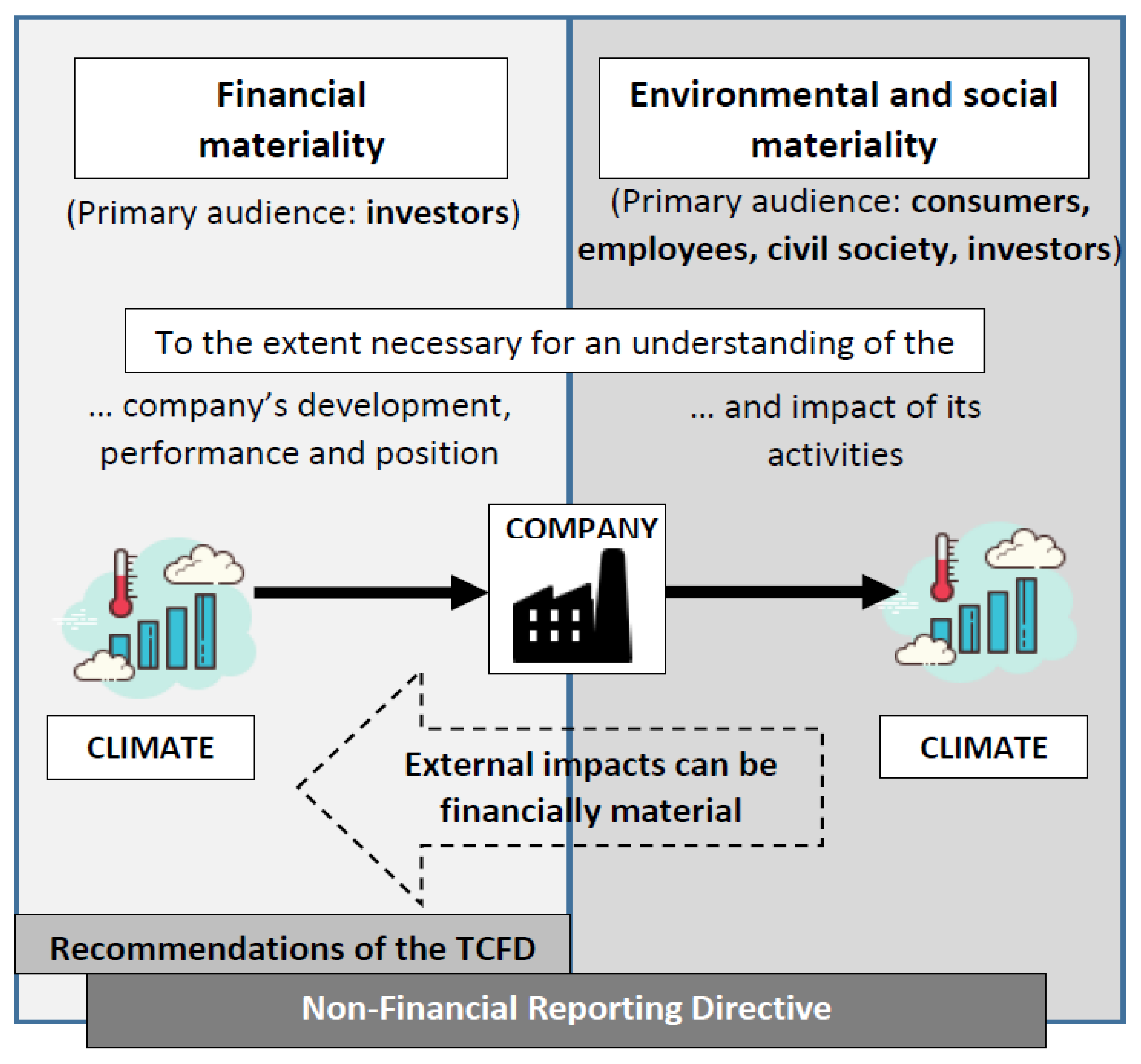

Figure 1).

On the European Commission’s mandate, in 2020 the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) and European Lab launched the Project Task Force on preparatory work for the elaboration of the EU’s non-financial reporting standards. The document that summarizes these preparatory works [

21] hopes for robust guidelines to operationalize materiality. These guidelines, besides establishing the direct and indirect levels of reporting the DM should be applied to (see EFRAG), aim to define and facilitate implementation of the impact and financial dimensions, without ignoring their interactions during the “key” process of materiality assessment. The summary report refers to the two DM perspectives as “impact” and “financial”, specifies the elements they must consider when identifying material sustainability issues, and stresses that “Financial materiality for sustainability reporting cannot be extrapolated from financial materiality for financial reporting” [

21]. Moreover, the report explicitly introduces the dynamic materiality concept. According to this, “Many impacts on people and the environment may be considered ‘pre-financial’ in the sense that they may become material for financial reporting purposes over time” [

21]. Both pillars and their interaction are clarified through a devoted visual (

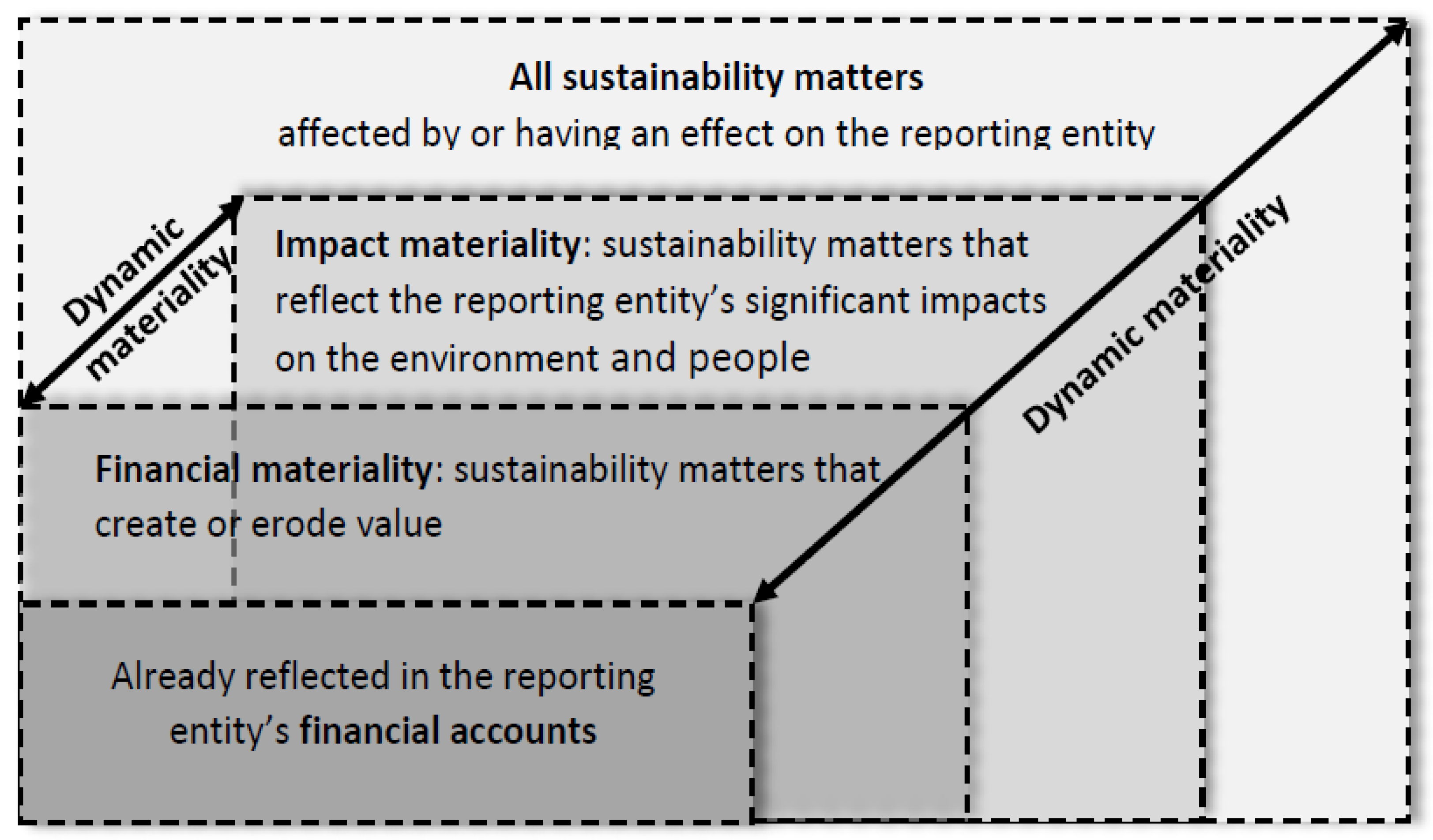

Figure 2). Finally, in addition to proposing a roadmap, the report requires that the draft version of the first series of standards, expected in 2022, includes the main conceptual guidelines aimed at making DM operative.

In the Proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) released in 2021 [

8] and twice revised in 2022, the European Commission welcomes this “double” syndicate of materiality. The proposal requires all the largest and listed companies, except those listed as micro-enterprises, to report on two orders of impacts—those suffered by companies in terms of performance and development (“outside-in” perspective), as well as those generated by companies on society and environment (“inside-out” perspective). Furthermore, the EC’s focus shifts from non-financial to sustainability information [

22], information that should be disclosed on the basis of one or both materiality perspectives.

In April 2022, EFRAG released a set of 13 exposure drafts of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRSs). The set includes two transversal standards (ESRS 1. General principles and ESRS 2. General disclosure requirements, strategy, governance and materiality assessment), plus 11 standards on three thematic areas (Environment, Society, and Governance). The exposure draft of ESRS 1 considers DM as a basic principle, namely, “the basis for disclosure of sustainability” [

23]. The exposure draft of ESRS 2 supports DM implementation by providing further indications.

The relevance of DM throughout the set of exposure drafts is specifically confirmed by questions 18–23. The latter are the questions that the online questionnaire of the public consultation process (period 29 April to 8 August 2022) devotes to DM (questions 18 and 19), impact materiality (questions 20 and 21), and financial materiality (questions 22 and 23). The summaries published online by EFRAG already highlighted interesting results [

24]. General data indicated that 49% of respondents believe the DM definition fosters the identification of sustainability information that would meet the needs of all stakeholders, while 46% did not agree. However, looking more closely at the data, one realizes that the respondents agree or not according to their nature. While the categories more heavily involved in materiality practices (i.e., non-financial companies and audit, assurance and accounting firms) are those that are mostly opposed to the definition of DM, the majority of the remaining categories welcome it.

Since the final drafting of the ESRSs is expected in November 2022, it will soon be possible to verify how the respondents’ feedback about DM will be included in the final version.

3. Relevant Literature: In Search of Double Materiality in International Research

In recent years, the development of the initiatives we referred to in the previous section has generated an increasing number of contributions on the subject of materiality applied to NFR.

These contributions range from reviews concerning definitions of materiality and/or declinations of the MAP [

7,

25,

26] to considerations on the theoretical impact of materiality [

27], from proposals for operational management of the MAP [

28,

29,

30] to studies carried out with a special view to assurance [

31,

32].

The literature stream devoted to the MAP disclosure investigated the determinants of such disclosure [

33,

34,

35] or focused on aspects such as stakeholder engagement [

36] and social constructs [

37] in integrated reporting.

Knowledge on the varieties and quality of materiality disclosures can also be gathered from other studies. These studies detected differences (e.g., the definition of what is material) and common aspects (e.g., the materiality matrix) [

1] in several versions of materiality disclosure [

38]. Moreover, regardless of the reporting context investigated, they found a plethora of gaps which undermined the quality of disclosure. Among these gaps, we list the following: (i) distortions in sustainability issues information [

39]; (ii) imprecision and lack of transparency in information on the MAPs [

40]; (iii) lack of detailed and comprehensive information on approaches used to define material topics [

41]; (iv) little information on materiality, stakeholders’ identification, and material topics identification [

42]. Guix et al. [

43] even found that managers interviewed about the opacity of the sustainability reports are reluctant to explain the decision-making processes and materiality criteria adopted.

It is striking that neither the literature on materiality disclosure has been inspired by the recent European materiality change, nor the inclusion of the “impact pillar”, has managed to make materiality one of the foci of research on NFDD [

44]. In the studies that examined NFI disclosure after the NFDD release, materiality was either not considered at all [

45,

46,

47], marginally considered, or considered as follows: (i) to score disclosure quality, both explicitly [

48] and implicitly, namely detecting impacts [

49]; (ii) as theme mentioned explicitly [

50] or implicitly, namely through impacts [

51] in the domestic implementations of NFDD [

52]; (iii) one of the quality indicators of sustainability reporting [

53]; (iv) one of the aspects encoded in the analysis protocol of a case study [

44].

The aforementioned considerations generate perplexities since the lack of clarity on the meaning of materiality, especially when considered with the different EU member states’ transpositions that the NFDD’s text allowed, has always been one of the main points of criticality in the provision [

18,

51]. Moreover, as a specific shaping of materiality, DM is studied within the EU regulation both in the context of sustainable finance reforms [

54,

55] and as an ambiguous [

2] outcome of the recent evolution of the meaning of NFI materiality [

56,

57].

However, “between the lines” of the more recent literature on NFR, more critical voices have started a debate on DM.

The real nature of the concept provided cues for its momentum. Indeed, since it needs practical application, its mere formal definition is not sufficient to define its content exactly [

5]. In the official EU documents, it is noted this content would remain ambiguous as it incorporates two conflicting perspectives of materiality—namely, those inspired by the GRI’s additive and the IIRC’s cumulative approaches [

2]. The ideological conflict between instances of investors and other stakeholders that DM expresses is therefore difficult to remedy [

58]. Likewise, the methodological question of the links among DM, financial objectives and risks still remains unresolved [

59]. Furthermore, DM conceals the potential of the financial capture of sustainability reporting capable of undermining the accountability that ISSB would seem to have fully grasped through its cautious incremental approach [

58]. Even if ISSB were to expand the range of requested information by inserting the so-called beta-information, it is pointed out that the accepted meaning of materiality would in any case configure a “sesquimateriality”, namely an intermediate materiality that does not reach the dignity of a full DM since it is still firmly related to the financial pillar only [

60].

Moreover, fearing that stakeholders’ opinions and interests in DM could be manipulated in favour of investors, namely toward practices that would be incompatible with the expected accountability function, it is questioned whether DM is sufficient for a European reform of the NFR aimed at focusing on accountability [

61]. Therefore, it is hoped that the standard setters will intensify the focus on dialogic responsibility to the extent of defining a type of materiality that even goes “beyond” the DM [

61]. The concepts of “stakeholder materiality” and “comprehensive materiality” [

62] could perhaps answer this need. Indeed, by specifying and/or expanding stakeholders, with interests and expectations considered, they go beyond the boundaries of the DM.

Others ask whether the distinction between sustainable and financial materiality even makes sense, which ultimately means wondering if a DM exists [

56]. Some experts answer that inevitably, in the long term, many aspects that are currently evaluated as material using the impact materiality perspective will flow into those evaluated as material using the financial materiality perspective. Those that then adopt this approach largely deem that the aforementioned question could be simply declassified by reducing it to the easier question of the time horizon to be considered in order to assess materiality [

56]. This dynamic materiality, indeed, only postpones DM [

13]. Both paths towards financial materiality [

63] and the exhaustion of the financial materiality [

64] of certain sustainability issues have been examined in the literature.

Despite the highlighted criticalities, the preference for DM was expressed by many categories of subjects, such as professional bodies and banking associations [

57] and users of NFRs [

65]. The preference for DM was also expressed in the context of the adoption of global sustainability standards in developing economies [

66].

Unlike what was found above by examining theoretical contributions, few empirical studies are interested in DM.

These few studies intended DM as a general framework for investigating changes in the CSR reporting practices of German savings banks [

67] or as a guiding concept for overcoming the weak sustainability disclosure found in Ghanaian companies’ reporting [

66]. The empirical study of the DM application has so far been mainly entrusted to sporadic works published in international outlets [

10], domestic languages [

68], or in mere abstract form [

69]. Notably, DM is among the aspects that Pizzi et al. [

10] detected when the relationship between financial and sustainability materiality is analyzed. In particular, the authors investigate the adoption of GRI’s and SASB’s standards by considering the integration of the SASB and GRI standards as a proxy of DM. In addition, Pavlović and Miler [

68] include DM among the aspects studied in order to investigate the current state of climate reporting by Croatian companies. On the basis of previous studies conducted on NFRs of large, listed EU companies, the authors set the hypothesis that the state of NFR in Croatia are lacking in terms of quality, scope and comparability in relation to the requirements of the NFDD. They tested the hypothesis by using both an anonymous survey and an analytical review of NFRs. Finally, DM is the approach to materiality that Zhongming et al. [

69] have detected by examining the NFR system of a company group operating in Asia. Through a case study, the authors investigate the most recent reporting practices, including new reports, that the company has recently adopted to communicate the company’s strategy in 2021, the turbulent landmark year of the pandemic.

Table 1 offers further details on the five empirical studies that, among those mentioned above, considered DM as one of the analyzed aspects rather than a framework or guiding concept. The table summarizes both some general aspects and the main findings that have been specifically detected regarding DM.

It is therefore interesting to underline that the existing few empirical contributions on DM focus on both European and non-European countries, thus expanding the potential scope of the DM. Furthermore, it is evident that, probably due to the too-recent introduction of the DM concept in the EU’s regulation, the scientific literature on the subject is still in an embryonic and almost entirely theoretical state, which still fails to provide any picture of the existing one. Although, to date, no knowledge is available about the possible solutions for implementing DM in MAPs (e.g., grafting by addition of DM, complete reconfiguration of MAPs, etc.), the debate on DM has already taken shape. However, such a debate will probably not fade away in the short term, because the first practices that gradually emerge will certainly provide new impetus to further development.

4. Research Design and Method

In light of the EU’s path towards sustainability reporting described above, we wondered what attitude towards DM the companies had shown in the most recent reporting practices. We aimed to understand whether they had been waiting for the emanation of ESRSs to definitely apply DM or had been proactive and applied DM prior to this step on the basis of prior EU guidelines that had already been released. Moreover, in case of early application, we aimed to discover whether the NFRs had been conservative or tended to radically overturn their model of materiality analysis disclosure.

The lack of empirical contributions on DM suggested we had to investigate the first experiences of DM adoption traceable in the NFRs of companies. Two arguments in particular led us to believe that it was interesting as well as important to fill the empirical gap by proposing a work that maps the recent NFR practices in search of pioneering experiences of DM and its disclosure. First, if it is true that the two pillars of DM increasingly collided when they began to be applied separately in practice [

65], then the need to explore what happens in companies’ NFRs becomes even more compelling in cases of joint application under the aegis of DM. Second, we felt the need to provide a concrete substratum to the extensive debate that has already developed, since history teaches us that business practices can overwhelm early theoretical arguments, leaving out critical issues and best practices that theoretical debates fail to grasp. Practical experience, indeed, often engulfs the debating arguments, as it makes it compulsory to bring unprecedented perspectives and solutions for dealing with problems not yet envisaged.

Therefore, in order to reveal commonalities and emerging differences between the pioneering adoptions and disclosure of DM, this article aims to study evolution, breadth and implementation methods of the DM concept in the NFRs of both European and non-European companies.

Indeed, although the DM has become mandatory in the EU, it seemed important to evaluate its impact all over the world by assigning a territorial scope wider than the strictly European one to our research objective. The following explains why.

Until a few years ago, with the exception of the few well-known pioneer experiences of single countries (e.g., South Africa’s 2009 King’s Code of Governance; French 2010 Grenelle Act II), NFR regulation was scarce and the drafting of NFRs was largely left to voluntary companies’ initiatives in most of the world. However, over the last 15 years, several national NFR provisions, both voluntary and mandatory, have spread across all continents [

70]. These provisions differ in type (public laws and/or regulations, self-regulations, codes and/or guidance, standards and/or guidelines, actions plans and/or programmes), issuer (governmental agencies, financial market regulators, stock exchanges, industry bodies), disclosure scope (information on more or less environmental, social and governance aspects such as, for example, climate-related financial risks, slavery, gender), recipients (listed companies, financial companies, large companies, public interest companies), and degree of obligation (voluntary vs. mandatory). In terms of the volume of reporting provisions issued in the period 2006–2020, Europe is the most active continent while Asia, contrary to what may be expected, is a close follower. Remaining continents show a much smaller number of provisions and, among these continents, North America is less active in the field [

70].

Remarkably, these provisions include a shift toward mandatory NFR.

For example, in Europe, a large proportion of recent provisions involve the countries that have implemented the NFDD through national measures since 2016 [

70], including the United Kingdom. After Brexit, this country still requires both large companies and specific industries to report on social and environmental performances [

71], while in 2018, the country revised its Corporate Governance Code by including reporting obligations. Moreover, outside the EU, Switzerland, a non-EU country where guidelines and standards for non-financial reporting are voluntary, in 2021 obligated large private and listed companies to make certain key information related to corporate governance available to investors. Even Norway, again not part of the EU, amended the Norwegian Accounting Act in 2017 in order to align reporting obligations of large private and listed companies to NFDD [

72].

As for the Asia-Pacific, in 2021 China updated disclosure rules related to the environmental and social responsibilities of large private listed companies. It is noteworthy that, in this country, mandatory rules on CSR information reporting systems of state-owned companies have existed since 2008. In South Korea, a series of regulations on NFI disclosure were issued in 2012, 2013, and 2015. In 2021, in order to encourage publishing transparent and comparable disclosures among large private and listed companies, the Guidelines on Disclosure of Corporate Governance were issued. Singapore also moved toward new rules for sustainability reporting of listed companies in 2018 and introduced a phased approach to mandatory climate reporting in 2021 [

73].

In Australia, despite the lack of a compulsory NFR as such, the current legal requirements for certain entities in terms of disclosing NFI are related to specific federal acts on Modern Slavery (2021), Workplace Gender Equality (2012), and National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (2007) [

74].

As for Africa and the Middle East, various countries have begun to implement NFR practices. Among them, it is worthwhile to mention Morocco, that in 2019 introduced non-financial disclosure requirements for ESG measures in annual reports of large private and listed companies; Tunisia, that in 2017 enacted the CSR Law; and Israel, that is playing a very active role in this area, activating various mandatory NFR tools [

75]. Moreover, in South Africa, the previous NFR obligations, which applies to all organizations regardless of their sector, size, and type, were updated in 2016 by removing explicit references to any standards. Moreover, a single national reporting system for the transparent reporting of greenhouse gas emissions was introduced in 2017.

In South America, a rigorous legal NFR framework has not yet been established and only Chile, which in 2021 set out obligations to report on ESG factors, adopts the most rigorous mandatory regulations. Remaining relevant initiatives throughout South America, although mandatory and CSR-related, do not include reporting obligations involving companies (e.g., the 2020 Colombia update of the National Action Plan).

Finally, in North America, the United States still imposes fewer regulations in this respect than other countries. However, although NFR is not mandatory yet, public companies must disclose relevant information on ESG risks and opportunities to key stakeholders, because companies are required to disclose any information that shareholders would reasonably need to make an informed assessment of an entity’s operations and business strategies. Moreover, the NFR topic has formed a part of the public debate since the November 2020 elections [

74]. In Canada, recent regulation includes topic-specific reporting provisions, such as those related to modern slavery [

70]. For more details on each country mentioned in this section, please consult the website

https://www.carrotsandsticks.net (accessed on 6 December 2022) [

75].

Hence, companies that compete in a globalized context face an increasingly fragmented NFR regulatory environment compared with the past. Each regulation that emerges can represent an obligation, if the company is directly involved as a recipient, or a benchmark, if the company deems it convenient to draw up NFRs that comply with rules that are in force in certain territories. Furthermore, each time a country introduces a new mandatory regulation on NFR and/or social performance measurement, a “domino effect” in other geographical areas is expected [

76,

77,

78]. Then, the extension of our research aims to non-EU countries seemed useful to evaluate the influence of the EU’s regulation on DM outside the Union. In summary, it seemed important that our aim makes it possible to verify whether and to what extent the EU’s DM can cross the borders of the Union.

To achieve the aforementioned research goal, an exploratory investigation was conducted through a document analysis of NFRs. This analysis was carried out employing a two-fold perspective—the qualitative perspective of the textual analysis, and the quantitative perspective of the measurement of the extent of feature occurrences.

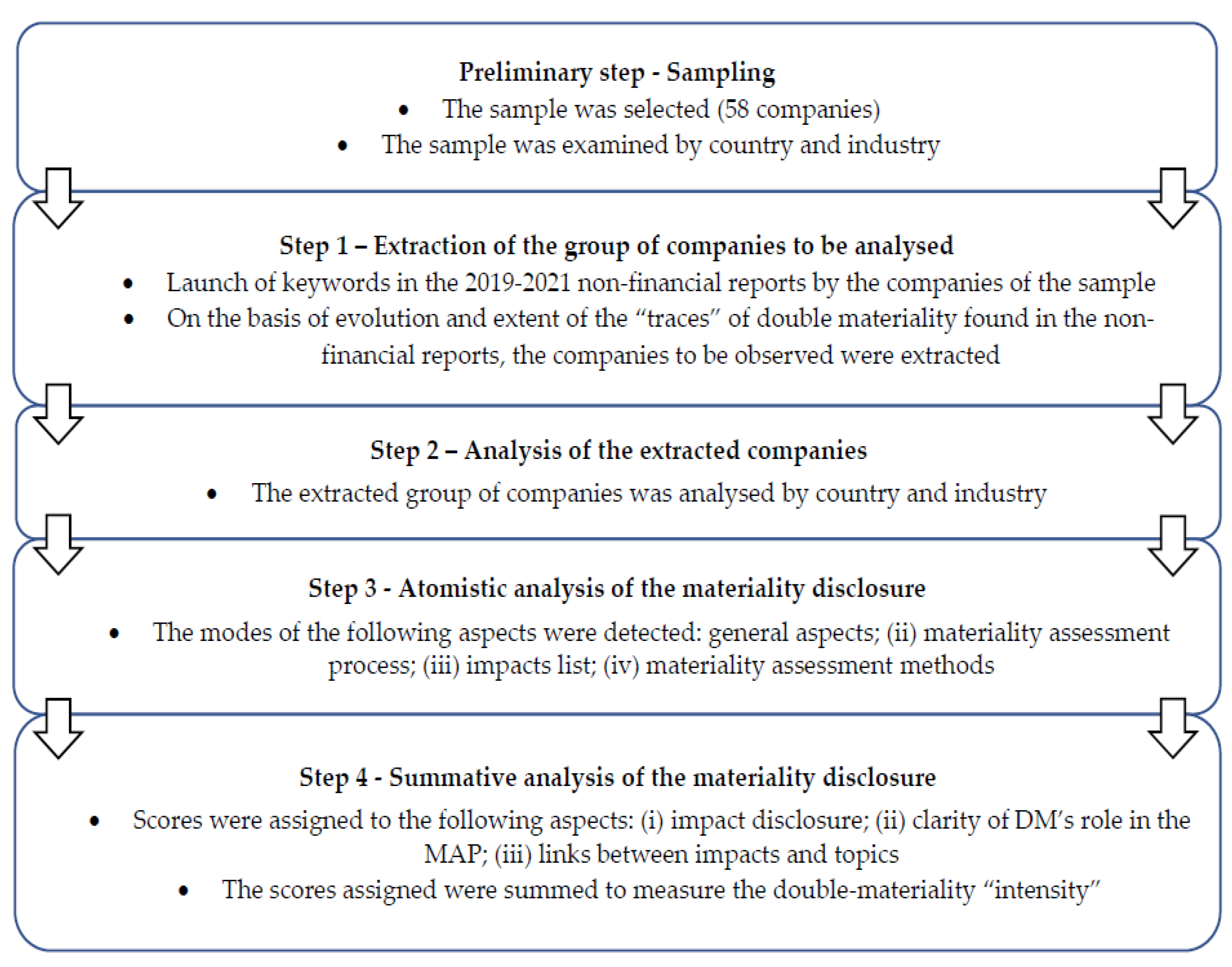

Figure 3 graphically summarizes the research process which we describe below.

During the preliminary phase of the research, we selected the group of companies to analyze.

In order to increase the likelihood of finding companies publishing NFRs to examine, we searched for a sample composed of “sustainability-oriented” companies. For this purpose, we deemed the Robeco Yearbooks a suitable data source fitting our research needs.

Indeed, as an international investment company that focuses on sustainability investments [

79], its research team develops the methodology for the annual corporate sustainability assessment that is used to determine the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. As such, Robeco (formerly RobecoSAM), analyzes companies along sustainability metrics since 1995 and has developed one of the largest global corporate sustainability databases.

Among the several activities carried out, Robeco annually publishes a Yearbook that reports on the results of the previous year’s corporate sustainability assessment, lists the companies that have been assessed, shows the sustainability performance of the world’s largest companies, and rewards the most virtuous of them with virtual medals. Therefore, we decided to focus on units that consistently show high sustainability performances—that is, companies that have over time performed better according to the Robeco assessment.

Then, in order to focus on steady “sustainability-oriented” companies, the period that was chosen to extract the group of companies to be observed was 2014–2021. This group was extracted through a funnelling process of gradual reduction of the units selected (

Table 2).

Among the companies that Robeco listed in its Yearbooks over the selected period, we focused initially on the companies permanently awarded with Robeco’s virtual annual medals and then on companies that, by our cut-off date (22 August 2022), had published online a PDF version of NFRs drafted in English language. This process led to a group of 58 companies, representing 5.64% of the initial list. Hereinafter we refer to this group as “the sample”, although it is a statistical sub-population not randomly extracted.

The sample was composed of 58 companies operating in 39 industries and whose headquarters were located in 21 countries.

When we examined how many companies operated in each industry, the following frequencies emerged: one company in 26 sectors; 2 companies in 10 sectors; 3 companies in 10 sectors; 6 companies in the Electric Utilities sector.

When we examined the geographical provenance, it emerged that 29 companies operated in 11 European countries as follows: single companies operated in Belgium, Finland, Portugal, and Sweden, 2 companies operated in France, Italy, and the Netherlands, 3 companies operated in the United Kingdom, 4 companies operated in Germany, and 6 companies operated in Spain and Switzerland. The remaining 29 companies operated in Asia (15 companies in 5 countries), America (10 companies in 4 countries) and Oceania (4 companies in one country, Australia).

Table 3 examines the geographical provenance by continent.

Europe and the rest of the world each represent exactly 50% of the sample.

After the sample selection, the NFRs of the 58 companies were analyzed by four subsequent research steps.

The first step searched for “clues” of DM in the NFRs that the 58 companies of the sample published over the three-year period 2019–2021. This three-year period was chosen because 2019 was deemed the beginning of a very relevant era for the expansion of DM. Indeed, as previously highlighted in

Section 2, in 2019 the European Commission explicitly introduced the expression “DM”, thus giving new impetus and substance to a concept that had (and has) not yet been fully developed. During this step, the search for the mention of the DM was carried out by the computerized launch of the following keywords: double materiality, financial materiality, financially material, and inward. In case of failed launches, we further focused on the materiality sections of the NFRs. Specifically, in order to be sure that no important clues had been lost, we launched the keyword “impact” in those sections. Despite the emergence of three additional companies, we did not extract them since they use the term impact only as “impact on the company” (i.e., financial materiality), and they never use the “impact materiality” expression. Hence, after devoted discussion, we decided to focus only on units explicitly showing a minimum of reference to DM and/or its pillars. Indeed, we deemed this search more consistent with our research aim that substantially stems from the EU’s concept of DM. We assumed that a precise mention of the fundamental terms that describe a specific concept introduced by a regulation is not only a formal proof of its adoption but also a substantial one, since it denotes an intentional and aware adoption.

In the second step we started the core analysis and studied the evolution, extent, geographical distribution and sectors of activity of the units whose NFRs presented “traces” of DM.

The third step examined the NFRs of the units whose NFRs showed traces of DM. Only the reports of the year in which more non-financial reports showed traces of DM were observed. In-depth reading of the sections dedicated to materiality made it possible to analyze separately a large series of aspects. The aspects investigated through this atomistic analysis can be grouped as follows:

- (a)

information on general aspects, such as DM description, reference to European regulatory sources or institutions involved in DM, and mention of dynamic materiality;

- (b)

information on the materiality analysis process (MAP), namely the existence of graphic or narrative schematization of MAP’s phases, links between phases, inclusion of the GRI’s issue prioritization phase, and materiality matrices;

- (c)

information on impacts in the list of topics, namely indication of the impact nature, intensity, direction, and level; and

- (d)

methodological information on MAP, namely information on data sources to identify issues and/or impacts, methods used to weight impacts and combine the pillars, data management tools and digitalization.

Finally, in the fourth step, we carried out a summative analysis aiming at experimenting with an initial transversal reading of some aspects identified in the previous step. This analysis attempted to weigh the “strength” of DM adoption/disclosure by qualitatively evaluating the following three aspects: (i) the mention of the two types of impacts (scores: 0/1/2); (ii) the clarity of the role played by the DM in the MAP (scores: 0/1); and (iii) the indication of links between themes and impacts (scores: 0/1). The scores assigned were then added and the resulting sums expressed by the following qualitative scale: very strong (4); strong (3); medium (2); weak (1).

6. Discussion

Our investigation has shown that only a few companies, about 17% of the sample, have introduced DM into their 2021 NFRs and that even fewer explicitly referred to DM (unit B) or to a DM’s pillar (unit H) in the two previous years. This means that, although the NFDD substantially established the dual perspective in 2014, the companies have delayed the implementation of the DM until 2021, when DM implementations significantly increased. Moreover, the pioneering companies we observed are not only European. This shows how the DM has also taken root outside the EU, both in geographical Europe, as in the case of the Swiss company (unit J), and in other continents (units C, D, F, and H).

The general aspects we researched provided interesting results that are summarized in

Table 24. In particular, our investigation highlighted that few companies introduce DM to the readers of their NFRs by supporting their understanding through visual aids or mentions of EU regulations or institutions. Regarding visuals, only two companies draw a devoted graph (unit F) or icons devoted to the impacts and their combinations (unit B). As for the EU, only 50% refer to its NFR framework or involved institutions. This provides evidence of the scarce aptitude toward the explanation of DM to stakeholders, although it represents the main novelty on materiality that recently emerged in the EU regulation. Moreover, the few references to dynamic materiality confirm that the explanation of the DM considered in its entirety, not only as a combination of pillars, is still in its initial stages and is provided only by the three virtuous units (A, B, and F).

The subsequent atomistic analysis on the disclosure about MAP’s phases, impacts, and methodological aspects provided interesting results that we further comment on below.

Regarding MAP’s phases (

Table 25), after having found that almost all the units (90%) explain the MAP’s phases using various textual and graphic proposals, we realized that the prioritization phase, typically ascribed to the GRI’s single materiality, is still present in 70% of cases. Additionally, 60% of the group publish a materiality matrix, a typical element of the GRI’s single materiality. The matrices found are always partially different from the original GRI’s proposal or are even used in a “DM way” where the two axes indicate internal and external impacts (unit D). All these findings demonstrate that the DM can be implemented both with (units A and B) and without (units F and J) full single materiality. In the first case, namely when the MAP includes both DM and single materiality (A and B), DM is performed after a single materiality assessment, the latter releases a materiality matrix, and the list of themes is considered the main output of the process. Moreover, both single materialities depart from the original GRI’s prioritization based on the binomial “influence on stakeholders-external impacts” because it analyzes the relevance (or the priority) of issues for the pair “stakeholders-company”. When DM is the focus of the MAP (units F and J), the materiality matrix is not drawn so that the reports expressly state their shift from a matrix-format to a table-type diagram in communicating key issues (unit F) or their abandonment of the topic prioritization (unit J). In the middle of these two extremes, a range of different solutions emerges. We can split such intermediate solutions into two groups. The first group (units D, G, and I) variously merge DM and single materiality so that the following cases were found: (i) single materiality incorporates DM, the latter being a tool for drawing the materiality matrix, namely the final MAP’s output whose axes once again represent relevance for the pair “stakeholder-company” (unit I); (ii) DM is the MAP’s focus, so that the axes of the materiality matrix presented represent DM’s pillars; additionally, the influence on stakeholders, namely a typical feature of GRI’s single materiality, can be found both in the text and in the diagram’s dots (unit D); (iii) as in the previous case, the two materialities are merged in a step that adopts three perspectives (the two DMs’ pillars and the stakeholders’ one), while the materiality matrix is not presented at all (unit G). The second group (units C, E, and H) offers contradictory narratives that do not allow us to precisely understand what the relationship between double and single materiality is. Not even the materiality matrix can act as proof of the presence of the single materiality. Sometimes it is not presented (unit C), and when it is, the same distortion found above with respect to the GRI approach is repeated (unit E). In addition, sometimes (unit H) the label of the “distorted” axis (business impact) is not very clear since the text also introduces the concept of “business (financial) impact”.

What has been said above on the MAP’s phases disclosure calls for urgent standard setters’ clarifications, especially the GRI’s. Indeed, the removal of the materiality matrix from 2021 GRI 3 has evidently not been sufficient to completely remove its use and the same distortions that previous studies detected. Moreover, a report (unit D) even presents the internal and external impacts in the form of a matrix, indicating the degree of influence on the stakeholders for each theme (y-axis in the GRI’s matrix). This could even be an example of pioneering practice that explains the new DM in a matrix format to foster readability of accustomed stakeholders to visualize materiality information in this graphic form.

Furthermore, the offered narrative on the DM role in the MAP is sometimes confused, ambiguous, and even incorrect. We found confusion when a lot of sources and reporting standards were described without clarifying phases of the MAP at all (unit I). Moreover, we found ambiguity when the NFR stated, on one side, that the DM permeates the MAP prioritization and that, on the other side, the prioritization matrix drawn is based on a dual analysis of internal/external relevance rather than impacts (unit E). An incorrect reference is even provided by a company that ascribes the DM to GRI 3 (unit I). Moreover, to be truly core to MAP, DM should support the issue rating and not only the issue listing, such as the one we found in a report where, despite judging the DM’s intensity as strong, the rating is first entrusted to the company and subsequently only validated by the stakeholders (unit J).

In addition, the atomistic analysis of the disclosure of the impacts in the issue list provided interesting results (

Table 26).

Results obtained showed that apart from a large variety of more or less detailed modes of providing information about links existing between topics and impacts, a lack of disclosure on intensity, direction, and level of the impacts emerge. However, when information on impacts exists, it does not automatically mean that a good disclosure exists. When a report indicates the GRI ambits (economy, environment, society) each topic impacts on, it is not sufficient to refer to the external pillar (i.e., the GRI perspective), because the economic impacts, if not specified, could be also internal (financial) impacts. Hence, the three-fold economy-environment-society type of information cannot be conveyed if it is presented by merging external and internal impacts (unit J). Moreover, information on the stakeholder categories each topic impacts on (units D, E and G) should be better clarified according to the DM’s intensity and the role of the GRI’s single materiality in the MAP. Specifically, where the DM is “weak” (C, H, and I), it is not always clear whether the issue list aims to summarize the synthetic judgment traditionally expressed by the y-axis of the GRI’s materiality matrix (i.e., traditional single materiality perspective), or whether the list refers to external impacts described by stakeholders’ categories (ex-DM). Therefore, it seems that imaginative narratives and taxonomies are enough for some companies to “dress up” in DM and obscure the bare information on the links between the impacts and the topics they provide.The last aspect we atomistically analyzed was the methodological information provided (

Table 27).The results highlighted a striking contrast between the many textual narratives, sometimes even excessive, devoted to data sources, and the absence of clarifications regarding measurement and final convergence of the impacts. Disclosure on data management tools is also lacking. Despite being consistent with the deficiencies that previous studies on materiality disclosure detected [

40,

41], the widespread reticence on criteria and tools we found now appears even more incomprehensible, since it is unlikely the DM did not request or require (now and hereinafter) the adaptation of the technological supports previously used (e.g., software), or even the introduction of more advanced tools of data collecting and analysis (e.g., platforms).

Finally, through the systemic analysis performed we provide evidence of very different intensities of DM applications (

Table 28).

The range of intensities we obtained allowed us to observe that only 40% of laudable cases of very high (units A and B, that score 20%) and medium (units F and J, that score 20%) disclosure of DM and its links with the MAP exist. Cases of low (units D, E, and G) and very low disclosure (units C, H, and I) are the majority. These latter groups score 30% each. The weakest cases, when studied in depth, reveal a “lame” (unit H), hidden (unit C) or opaque (unit I) DM. This prevents a detailed check of how DM was implemented and sometimes, when the company seems to consider only the financial pillar (unit H), even casts a shadow on the possibility of affirming that the DM has really been implemented. In this case, similar to the ISSB’s conservative paradigm [

11], the DM language has been captured by the NFR of unit H. However, a pillar is not enough to affirm that the DM has been partially applied, and nor is the financial pillar that cannot transform the information for (solicited or impacted?) stakeholders into the impact pillar. In sum, DM requires not only another pillar, but also the combination of the two pillars.

7. Conclusions

The discrepancy between the early debate on DM, considered as the meaning of materiality accepted by the EU regulation on the NFR subject, and the few empirical scientific contributions dedicated to DM disclosure, has oriented our research interest towards the investigation of the most recent pioneering experiences of DM of a sample of both European and non-European companies operating in several industries.

Our investigation of 2019–2021 NFRs has shown that only a limited number of companies, mainly European and operating in service industries, showed a proactive attitude towards DM, and largely in 2021 NFRs. Such companies have explicitly and consciously approached DM, albeit with different variants and intensities. However, most companies we observed still neglect the new approach to materiality. It is likely that, in order to proceed towards more solid implementations, they are awaiting further developments of the newest European sustainability reporting framework based on ESRSs, and the entry into force of GRI 3, expected in 2023.

The analysis of the 2021 NFRs for the ten companies that showed signs of DM has highlighted a wide variety of solutions proposed by practitioners to insert DM in their MAPs, as well as to report on these aspects through graphic and textual narratives. As regards MAP, for example, the following solutions emerged: renewed MAPs only oriented to DM, the addition of a “DM phase” to previous single materiality phases, and the merger of single materiality and DM in certain MAPs’ phases. As for narratives chosen, apart from effective and aware solutions that in several aspects could already represent benchmark practices, unconvincing or unnecessary prolix narratives emerged that often accompanied timid or unclear DM implementations. For most companies, the weakest disclosure usually referred to dynamic materiality as well as the binomials “impact-issues” and “criteria-tools”. This means that our study provided evidence both of best practices that already can be appreciated, and large uncovered areas of information that companies could look at. In the next few years, both aspects can become an opportunity to draw comprehensive and transparent sections of NFRs devoted to materiality.

The output of the systemic analysis performed also showed differences in intensity of DM application. While the strongest intensities we detected provided evidence of a handful of few proactive companies that have embraced DM in a clear and effective way, the low intensities cast a shadow on the possibility of affirming that DM has really been implemented in all these cases.

This work has implications for international organizations and standard setters involved in NFR, scholars, and businesses. For the EU, it provides evidence of the extent of the spread of DM in the world, in Europe and in the EU, as well as providing a measure of European companies’ reactivity to the EU’s regulation on NFR. In addition, it suggests EU institutions prioritize the importance of operational guidelines on their agenda, since the forthcoming increase in the number of NFRs will exacerbate the flourishing of a plethora of solutions whose comparability must be fostered now [

80]. Likewise, the study demonstrates the need for a more precise description of GRI’s materiality, especially focusing on its differences to DM. GRI should clarify how much its impact materiality is close to the DM’s external pillar. The more they overlap, the more the GRI’s single materiality assessments will be included in DM-oriented MAPs. On the other hand, the more they diverge, the more DM and single materiality will represent the steps of separate MAPs. Moreover, our analysis provides evidence to GRI that the removal of the materiality matrix from GRI 3 has not yet implied its removal from NFRs. Companies that still draw a materiality matrix continue their practices of changing the original GRI’s axes. Instead, we incidentally found an extensive use of the Cartesian axes to disclose stakeholder engagement outcomes in the materiality sections. This use for purposes different to those of the materiality matrix, besides the case of DM pillars represented through Cartesian axes, demonstrates how much the companies are accustomed to the matrix visual format the GRI denied in 2021. Furthermore, this study offers motivations to continue investigating the companies’ narratives on DM. Indeed, there is the risk that the increasing complexity detected in MAPs generates confusion in the disclosure. Finally, the contribution allows companies to know the most recent behaviour of their peers in terms of DM. Additionally, this study provides practitioners with a basic set of best (such as DM and MAP graphical visualizations) and worst (such as unclear and contradictory textual narratives) practices.

The study presents two main sets of limitations. The first group involves the sample itself. Its small size, although originated through a process of extracting a statistical subpopulation, did not allow for effective descriptions through percentages, and precluded both the clustering of DM patterns and statistical associations. The multiple sectors of activity also prevented industry-based conclusions. The second group stems from the type of analysis techniques that were used. The use of keywords to search for traces of DM can risk undersizing the phenomenon. Indeed, there may be cases of substantial application of the DM that are not accompanied by a narrative that includes the terms we have selected. However, since it was an initial pioneering survey concerning the EU’s DM, the work focused on searching for cases that were explicitly compliant with EU regulation. Including other cases would have been equally risky since, in compliance with specific indications coming from the technical bodies of the EU, it would have implied making assumptions about proxies of substantial application of the DM, even in the absence of the use of the expected terminology. However, even these assumptions would have been risky as they may have oversized the phenomenon. Therefore, we have preferred to assume the first of the two risks by isolating the cases of conscious and formalized adoption of the EU’s DM. Moreover, the textual analysis of the NFRs was a “soft” content analysis that generated outputs (i.e., codes) of equal hierarchical rank for each aspect, rather than a complex output of hierarchically-organized codes. Further, latent patterns among codes were limited to our explorative summative analysis. In addition, the latter analysis ranked DM intensity on the basis of only three aspects, which were mostly evaluated on a dichotomous basis.

Future studies on the disclosure of the DM could overcome these limitations. Indicatively, the first group of limitations could be overcome by conducting further exploratory and descriptive analyses on larger groups of companies, as well as on samples focused on specific geographical areas and/or industries. These investigations can be subservient to the needs of both the practice, when revealing models and best practices, and standard setting processes, when revealing distortions and worst practices. Furthermore, through careful monitoring of the substantial orientations expressed by the MAPs, it will also be possible to understand which contenders, in the sustainability reporting arena, will be the real “winners”. However, the path traced by the EU in terms of materiality delineates an obligatory “two-pillar” path which thousands of companies will inevitably soon have to deal with. As for the techniques of analysis, investigation of additional aspects of DM adoption and disclosure, such as information on the links with risks, could make the framework of the knowledge on DM practices more complete. Moreover, further more sophisticated summative analyses based on indexes could be carried out in order to discover underlying models of DM that certain narratives could hide.

Therefore, while waiting to verify the innovative solutions companies will give to a concept which is abstract in nature [

5], this work has already detected specific shortcomings in the DM information that are added to those that existing studies on materiality disclosure have outlined so far [

25]. Although, on the one hand, “pre-financial” evaluation exercises of dynamic materiality, on the other, the nature, direction, level and intensity of the impacts, are two among several novel aspects introduced by the EU’s approach to materiality, we found several weaknesses in their disclosure that provide a special warning for all subjects involved in forthcoming European NFRs. It is also surprising that, in an increasingly digitalized world, even the technology applied to the MAP constitutes a weakness of the NFRs, as well as that of institutional documents [

81].

Upon the conclusion of this article, both the European Parliament (on 10 November 2022) and the European Council (on 28 November 2022) formally adopted the CSRD. In light of this, further guidance [

82] on the ongoing Directive is a good opportunity to better explain what “adopting the DM” from the EU point of view means. Indeed, it would be very useful to clarify whether, to be compliant with the EU regulation of the Directive, it will be mandatory to adopt specific rules (for example those of the expected ESRSs) or whether another kind of substantial DM will also be admitted, such as, for example, that of compliance with two sets of standards, each inspired by a distinct pillar of the DM. This would be particularly relevant, among many aspects, for both theoretical and practical reasons. From a theoretical point of view, the more the European concept of materiality admits “minor” forms of compliance (i.e., the parallel application of non-EU NFR standards focused on each of the two DM pillars separately), the more the holistic view of the EU’s DM would be weakened. In this aim, the dynamic materiality could represent a fundamental distinctive element of this DM. By better circumscribing dynamic materiality, the EU would give DM a synergistic trait that would decisively distinguish it from the application, albeit perfect, of two series of standalone standards (financial-oriented and impact-oriented) that release unrelated informative results. From a practical point of view, the question of the best definition of the EU’s DM is relevant in light of the mandatory assurance that the new Directive introduces. We wonder how assurers can operate without having precise indications on the rules that a report must comply with. From a strictly operational point of view, it will be important to clarify whether the EU’s DM obliges the integration of the two pillars or if it admits their mere juxtaposition. Indeed, the latter case would imply the acceptance of the separate adherence to individual standards dedicated to one pillar each. As a consequence, in this case, the selection of the material information to be reported on would take place on the basis of outputs resulting from uncorrelated materiality assessments oriented to unconnected pillars.

Hence, if the clarity of the definitions of materiality and the quality of the devoted guidelines does not improve, the conceptual issues that have arisen around DM (even before its application) will not be solved. DM currently represents another version of materiality, coexisting with at least two other versions, namely GRI’s and ISSB’s, and the NFR scenario can only get increasingly complicated. In the meantime, we await the operative declinations of DM and the choices of their disclosure that the NFR practice will offer us in light of the expected completion of the European regulation of sustainability reporting.