Analysis for Conservation of the Timber-Framed Architectural Heritage in China and Japan from the Viewpoint of Authenticity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

2. Methodology

3. Case Studies

3.1. The Regulations of Conservation of Cultural Property in China and Japan

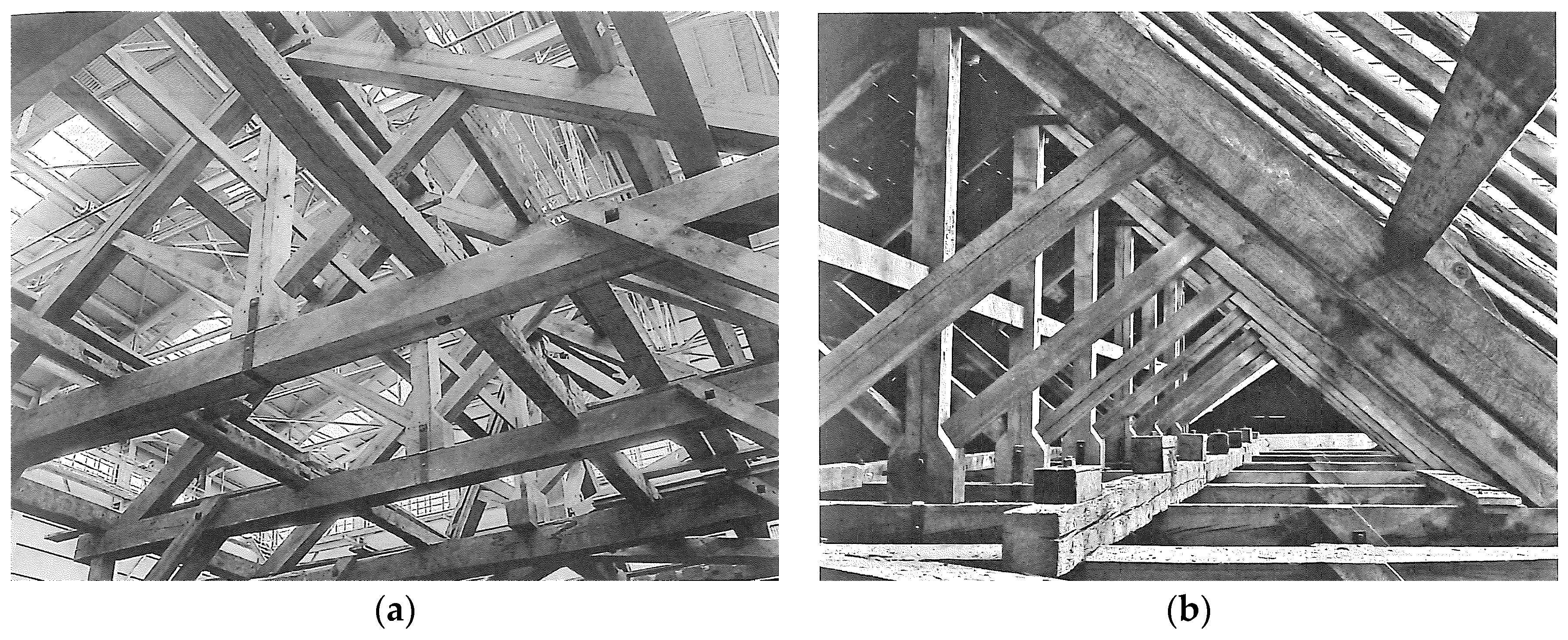

3.2. Restoration Cases in China

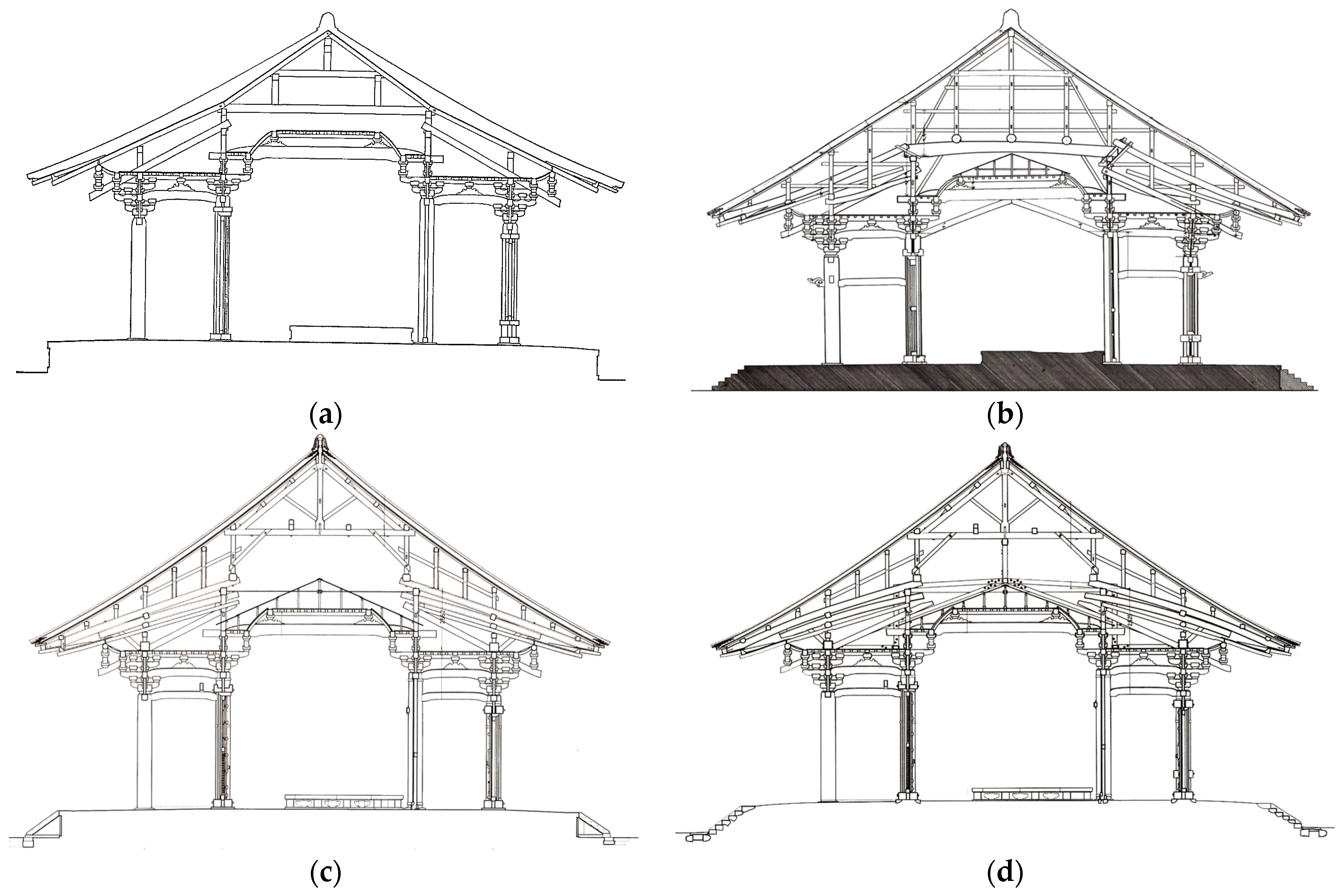

3.2.1. The Restoration of the Main Hall of Nanchan Temple

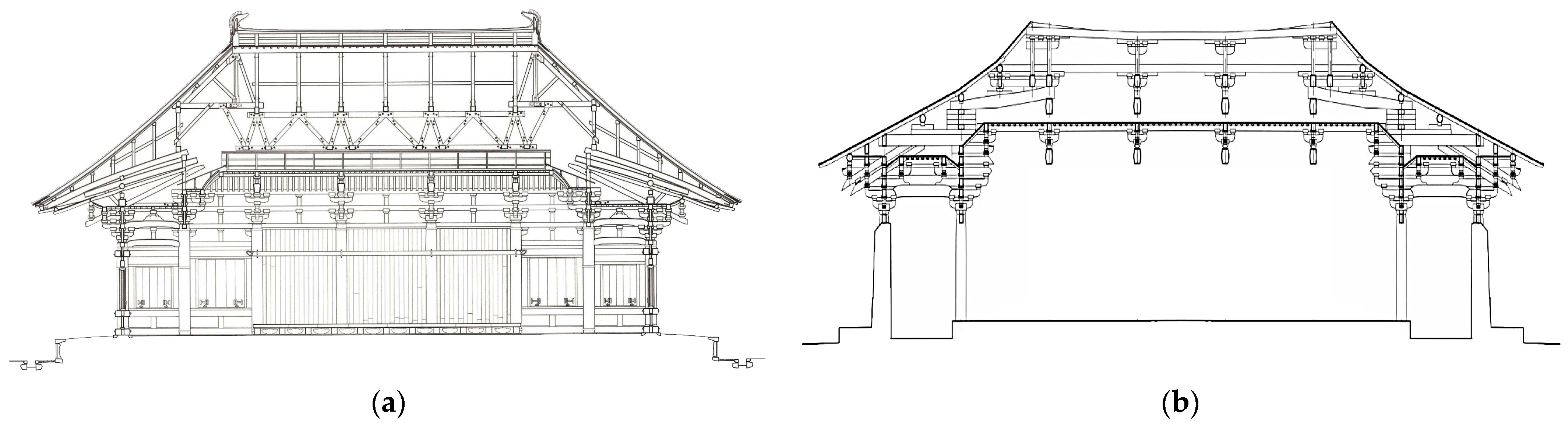

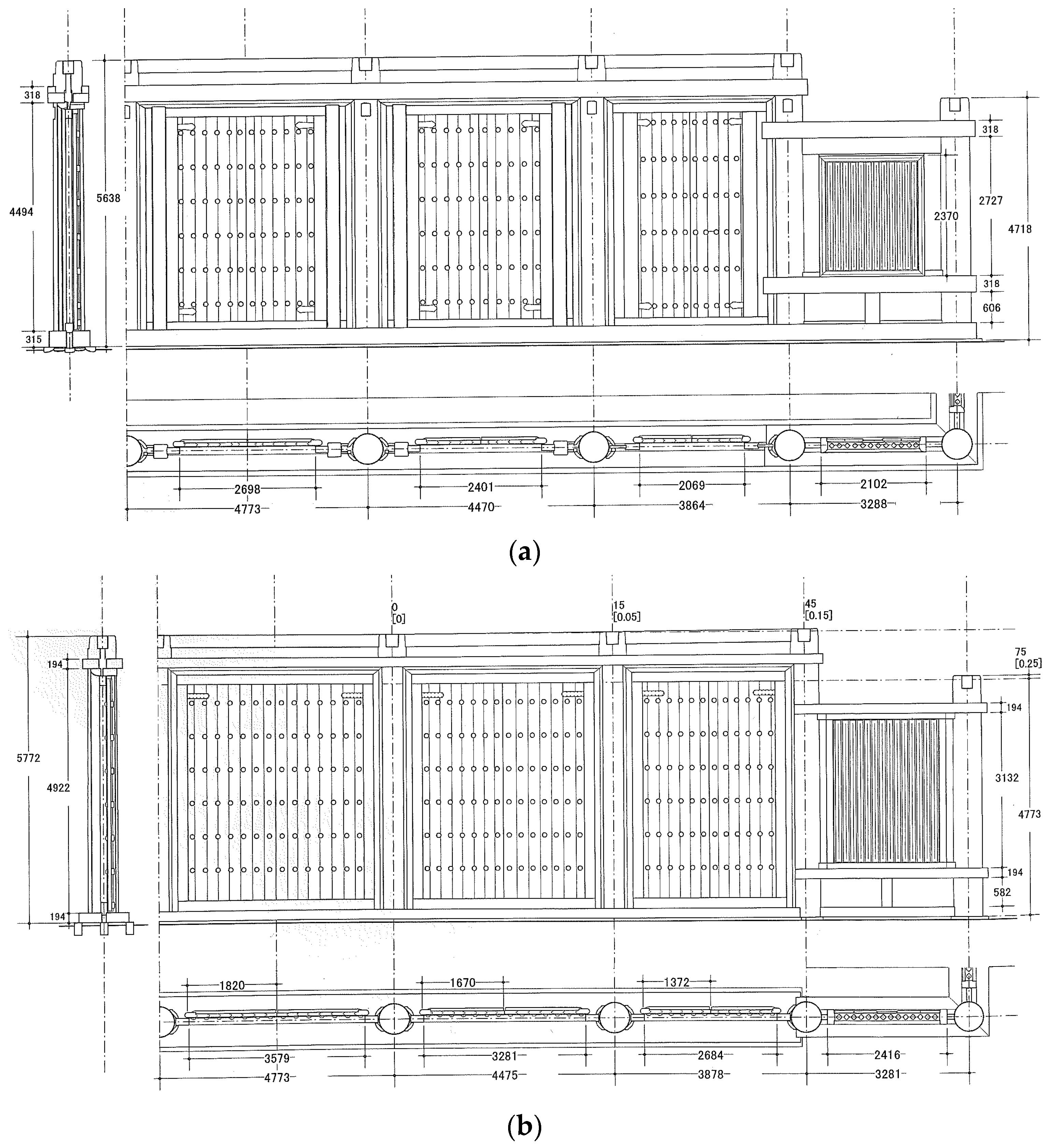

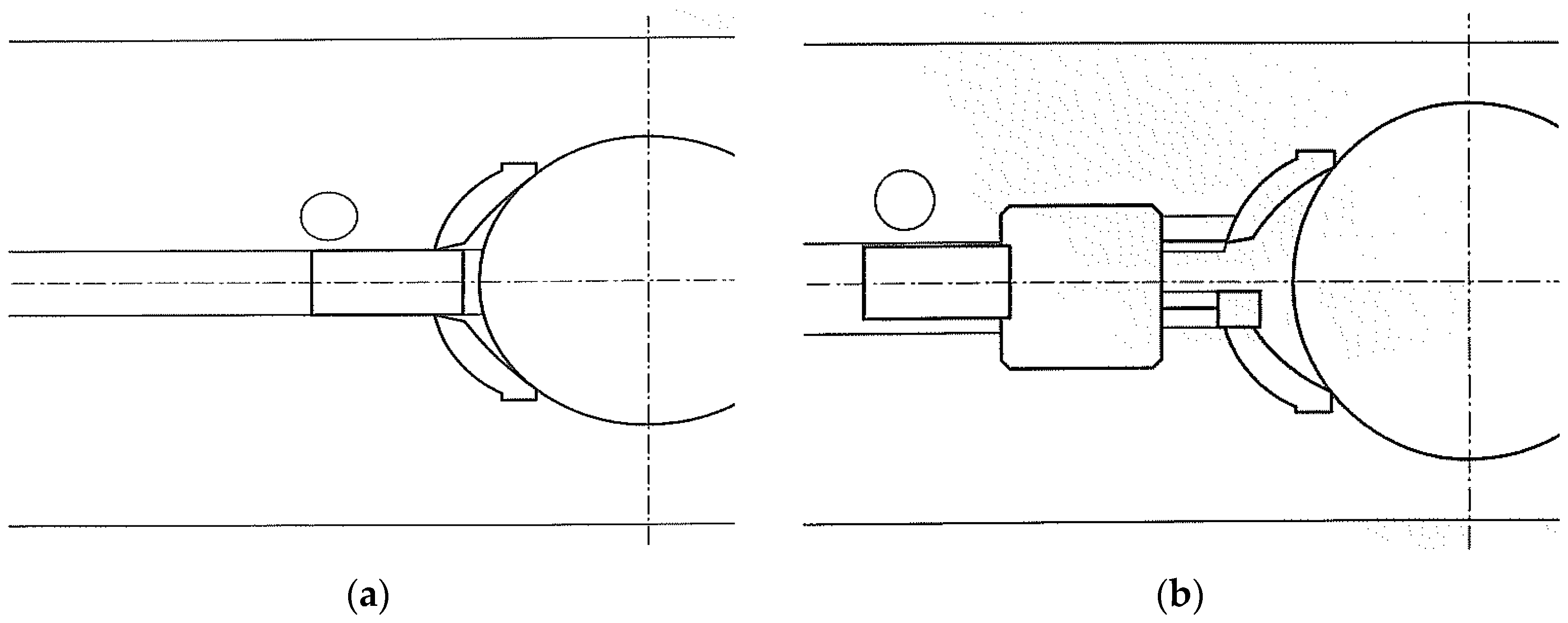

3.2.2. The Restoration of the East Main Hall of Fogaung Temple

3.3. Restoration Case in Japan

4. Results and Discussions

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W. Reflection of “Authorized Heritage Discourse” and Its Localization in China: Discussion on Some Keywords; Tianjin University: Tianjin, China, 2018; Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Dissertation/Article/10056-1022681542.nh.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese)

- The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (UNESCO, 1977). Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/content/900491036.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- The Nara Document on Authenticity (ICOMOS, 1994). Available online: https://icomosjapan.org/static/homepage/charter/declaration1994.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- The Venice Charter (ICOMOS, 1964). Available online: https://icomosjapan.org/static/homepage/charter/charter1964.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- The General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Issued the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (UNESCO, 1972). Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Charter for the Protection and Management of Archaeological Heritage (ICOMOS, 1990). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/arch_e.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- The Burra Charter (ICOMOS, 1999). Available online: https://icomosjapan.org/static/homepage/charter/others1981.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Principles for the Preservation of Historic Timber Structures (ICOMOS, 1999). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/wood_e.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- The Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage (ICOMOS, 1999). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/vernacular_e.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage (ICOMOS, 2003). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/structures_e.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- International Symposium on the Concepts and Practices of Conservation and Restoration of Historic Buildings in East Asia (ICOMOS, 2007). Available online: http://www.icomoschina.org.cn/uploads/download/20210312144359_download.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Niglio, O.; Valencia Mina, W. Reducción Del Riesgo Sísmico Para El Patrimonio Arquitectónico. Una Com-paración Entre Experiencias de Colombia y Japón. Apuntes. Rev. Estud. Sobre Patrim. Cult. 2015, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakayam, K. A study of Conservation and Maintenance Methods for Japanese Heritage Buildings; Tsinghua University: Beijing, China, 2013; Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Dissertation/Article/10003-1015007150.nh.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese)

- Chang, Q. A critique of “authenticity” in the restoration of historic buildings. ARCH Educ. 2009, 3, 118–121. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/SDJZ200903020.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Lu, Y.Y. The confusion of historic preservation and authenticity. J. Tongji Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2006, 5, 24–29. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/TJDS200605004.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Zou, Q. A theoretical discussion on the “principle of authenticity” in the conservation of architectural and historical heritage. South. Const. 2008, 2, 11–13. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/NFJZ200802005.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Lv, Z. Revision of the Guidelines for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage Sites in China and the Development of Cultural Heritage Conservation in China. Chin. Cult. Herit. 2015, 2, 4–24. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/CCRN201502002.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Lv, Z. A review of Chinese legislation on the protection of heritage buildings since 1949. Essays Hist. Archit. 2002, 3, 152–162+276–277. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z. The value of heritage buildings and its conservation. Sci. Decis. Mak. 1997, 4, 38–41. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/KXJC199704007.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Chen, Z.H. International Charter for the Conservation of Heritage Buildings and Historic Areas. Wordle Arch. 1986, 3, 13–14. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/SJZJ198603003.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Zhu, Y.J. Cultural effects of authenticity: Contested heritage practices in China. Int. J. Asian Stud. 2015, 21, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, R. Monitoring of Deformation of The Foguang Temple’s East Main Hall Under the Concept of Preventive Conservation. In Proceedings of the 27th CIPA International Symposium “Documenting the Past for a Better Future”, Ávila, Spain, 1–5 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, N.S. The Tang Architectural Icon and the Politics of Chinese Architectural History. AR Bull. 2004, 86, 228–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, L.M.; Bill, L.C.; Li, S.S. The Evolution of the Timber Structure System of the Buddhist Buildings in the Regions South of the Yangtze River from 10th–14th Century Based on the Main Hall of Baoguo Temple. Inter. J. Arch. Herit. 2019, 13, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrichsen, C. Authenticity in Japan. Authenticity in Architectural Heritage Conservation; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.J.; Huang, J. Analysis of the Differences Between Chinese and Japanese Traditional Wooden Architecture. EAR Environ. Sci. 2020, 510, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Traditional Wooden Architecture has Far-reaching Influence (Light of Inheritance). Available online: https://m.gmw.cn/baijia/2022-04/02/1302878806.html (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Tsinghua University Architectural Design and Research Institute, Beijing Tsinghua Institute of Urban Planning and Design, Institute of Cultural Heritage Conservation. Report on the Architectural Survey of the East Main Hall of Foguang Temple; Antiquities Press: Beijing, China, 2011. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wu, C. Examining the Object of Preservation of Chinese Culture Heritage and the Historical Changes from Late Qing to the Republic. J. Arch. 2018, 7, 95–98. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/JZXB201807020.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Qi, Y.T.; Chai, Z.J. The main hall of Nanchan Temple restoration. Artifacts 1980, 1, 63–75. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/WENW198011006.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Zha, Q. Early conservation practices of Chinese cultural heritage (1). Chin. Cult. Herit. 2018, 1, 78–86. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/CCRN201801012.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Qi, Y.T.; Du, X.Z.; Chen, M.D. Newly Discovered Ancient Buildings in Shanxi Province in the Past Two Years. Herit. Ref. Collect. 1954, 11, 37–42. Available online: https://wap.cnki.net/touch/web/Journal/Article/WENW195411000.html (accessed on 16 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Office of Cultural Assets Preservation, the Board of Education in Nara Prefecture. Report on the Restoration Work at the TOSHODAI-JI KONDO, a National Treasure (Five Volumes in Total); Nara Prefecture, Board of Education: Nara, Japan, 2009. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

| Year | Regulations Issued |

|---|---|

| 1906 | The measures for the promotion of the preservation of antiquities were formulated, and all provinces were ordered to implement them. |

| 1928 | The government of the Republic of China established the Central Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities and, in the same year, the Ministry of Internal Affairs issued the Regulations on the Preservation of Places of Interest and Antiquities. |

| 1930 | Conservation of antiquities. |

| 1931 | Antiquities Preservation Act Enforcement Regulations. |

| 1961 | The State Council promulgated the Interim Regulations on the Protection and Administration of Cultural Relics, Interim Regulations on the Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage. |

| 1982 | Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics. |

| 2000 | Guidelines for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage Sites in China. |

| 2015 | Guidelines for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage Sites in China (Revised Edition). |

| Year | Regulations Issued |

|---|---|

| 1871 | The Preservation of Ancient Articles and Antiquities Law, the first preservation regulations in Japan, are issued. |

| 1897 | Ancient Temples Preservation Act released. |

| 1929 | National Treasure Preservation Act released. |

| 1950 | Law on the Protection of Cultural Property released. |

| 1996 | The Law on the Protection of Cultural Property is amended to add the registration of tangible cultural property. |

| 2004 | Amendment to the Law on the Protection of Cultural Property, addition of cultural landscapes, folklore technology protection system, extension of the registration system. |

| Year | Affiliations | Main Participants | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 | Society for Research in Chinese architecture | Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, Mo Zongjiang and Ji Yutang | Photographs, mapping, discovery reports. |

| 1951 | Yanbei Heritage Study Group | Mo Zongjiang et al. | Information on the Yanbei Heritage Expedition. |

| 1964 | State Administration of Cultural Heritage Shanxi Provincial Cultural Heritage Working Committee | Luo Zhewen, Meng Fanxing | A Tang Dynasty wall painting on the girdle of the Buddha’s throne in the center of the door panel was found to be inscribed. |

| 1973 | Central and local heritage practitioners | Qi Yingtao, Luo Zhewen et al. | Not available. |

| 2004 | Shanxi Institute of Ancient Building Conservation | Qiao Yunfei, Shi Guoliang, Chang Yaping et al. | Photographs, mapping drawings, survey reports, restoration designs. |

| 2005 | Taiyuan Huanzhong Geotechnical Survey Co. | Qin Jinsheng et al. | Report on the Geological Survey of the Foguang Temple. |

| 2006 | Institute of Architectural Design and Research, Tsinghua University, Institute of Cultural Heritage Protection, Tsinghua Institute of Urban Planning and Design, Beijing | Liu Chang, Wei Qing, Zhang Rong et al. | The Foguang Temple Survey Study Report, The Foguang Temple Conservation Plan. |

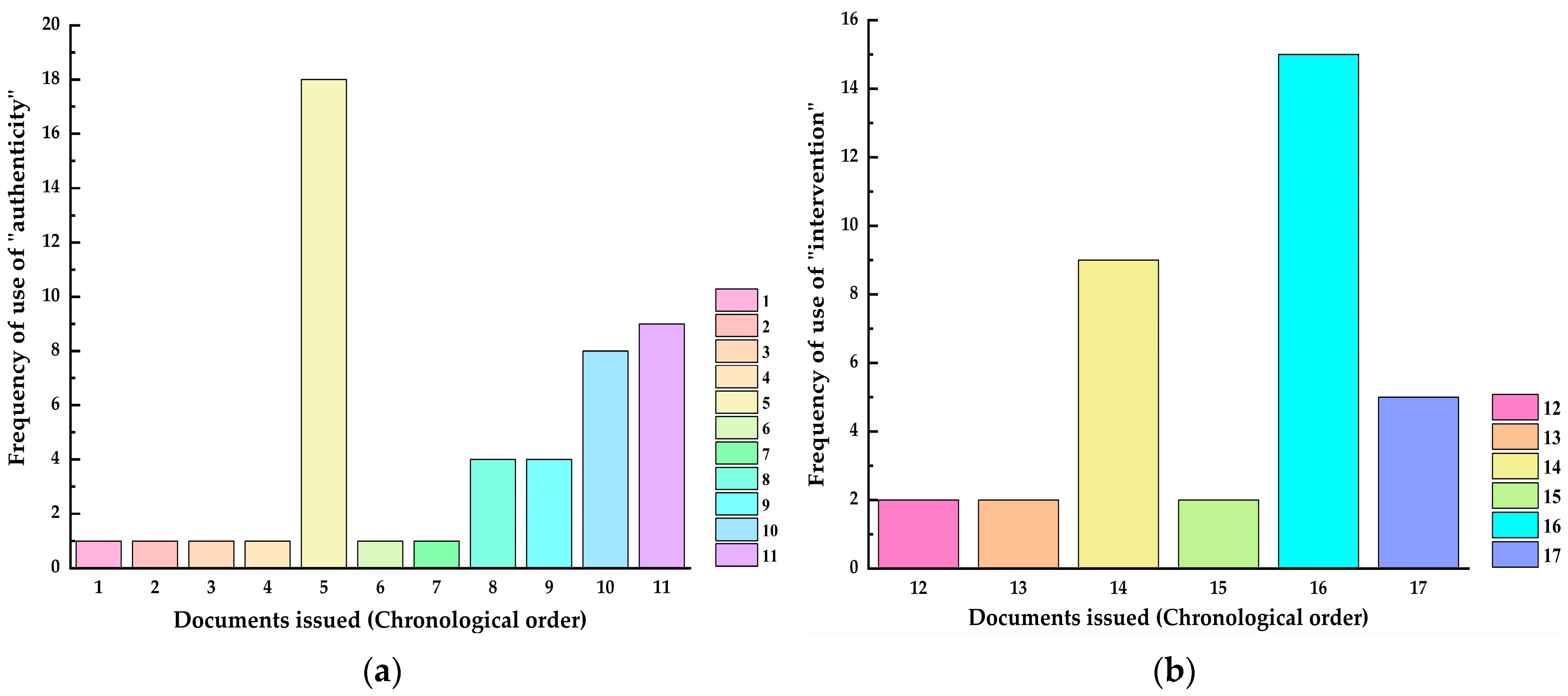

| No. | Year | Documents Issued | Times |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1964 | The Venice Charter | 1 |

| 2 | 1987 | The Washington Charter | 1 |

| 3 | 1990 | Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage | 1 |

| 4 | 1993 | Guidelines for Education and Training in the Conservation of Monuments, Ensembles and Sites | 1 |

| 5 | 1994 | The Nara Document on Authenticity | 18 |

| 6 | 1999 | Principles for the Preservation of Historic Timber Structures | 1 |

| 7 | 2003 | Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage | 1 |

| 8 | 2005 | Xi’an Declaration on the Conservation of the Setting of Heritage Structures, Sites and Areas | 4 |

| 9 | 2007 | International Symposiums on the Concepts and Practices of Conservation and Restoration of Historic Buildings in East Asia | 8 |

| 10 | 2008 | The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes | 19 |

| 11 | 2008 | Beijing Memorandum on the Conservation of Caihua in East Asia | 9 |

| No. | Year | Documents Issued | Times |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 1987 | The Washington Charter | 2 |

| 13 | 1996 | Principles for the Recording of Monuments, Groups of Buildings and Sites | 2 |

| 14 | 1999 | Principles for the Preservation of Historic Timber Structures | 9 |

| 15 | 1999 | Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage | 2 |

| 16 | 2003 | Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage | 15 |

| 17 | 2008 | The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jing, S.; Wang, W.; Masui, T. Analysis for Conservation of the Timber-Framed Architectural Heritage in China and Japan from the Viewpoint of Authenticity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021384

Jing S, Wang W, Masui T. Analysis for Conservation of the Timber-Framed Architectural Heritage in China and Japan from the Viewpoint of Authenticity. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021384

Chicago/Turabian StyleJing, Songfeng, Wei Wang, and Takeshi Masui. 2023. "Analysis for Conservation of the Timber-Framed Architectural Heritage in China and Japan from the Viewpoint of Authenticity" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021384

APA StyleJing, S., Wang, W., & Masui, T. (2023). Analysis for Conservation of the Timber-Framed Architectural Heritage in China and Japan from the Viewpoint of Authenticity. Sustainability, 15(2), 1384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021384