Sustainable Consumer Behaviors: The Effects of Identity, Environment Value and Marketing Promotion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Consumer Behaviors

2.2. Literature That Explains SCB

2.3. Identities

2.4. Values

2.5. Relationship between Altruistic Values and Moral Identities

2.6. Promotion

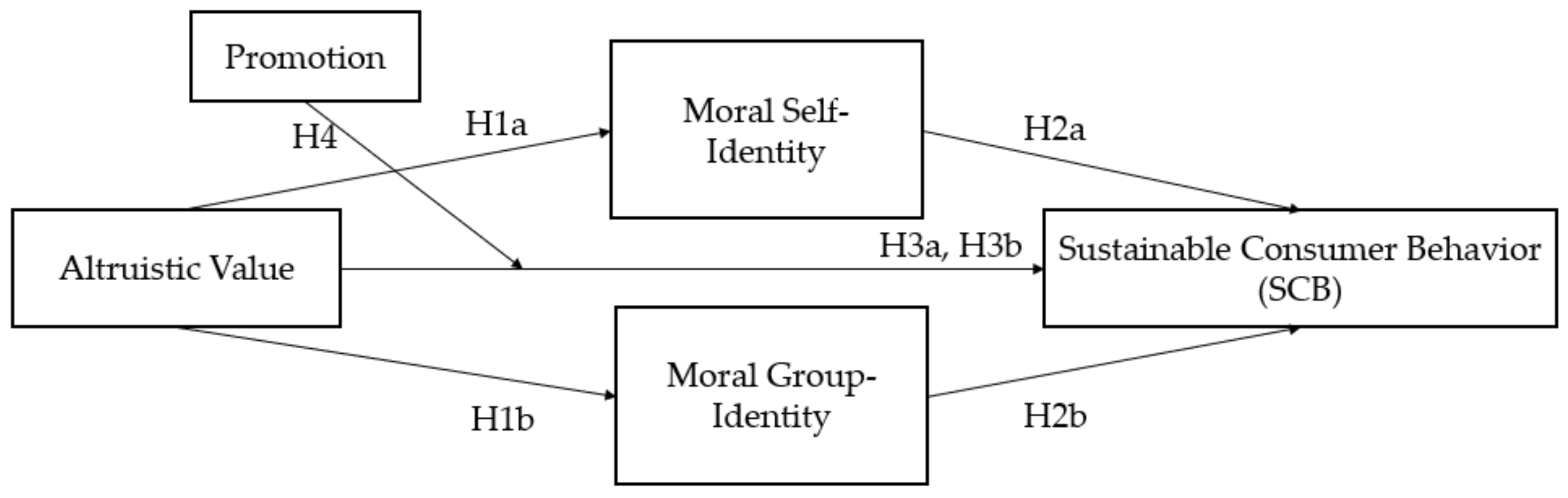

2.7. Present Study

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

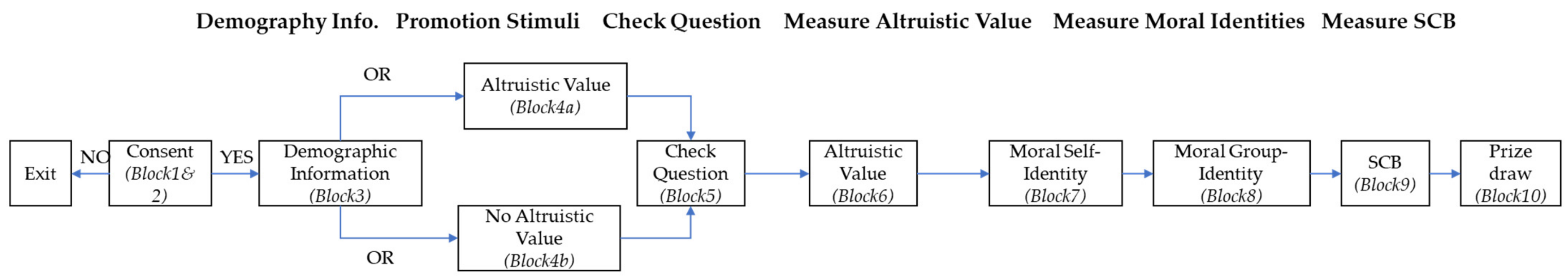

3.2. Procedure

3.2.1. Sustainable Consumer Behaviors

3.2.2. Moral Self- and Group-Identity

3.2.3. Altruistic Values

3.2.4. Promotion Stimuli

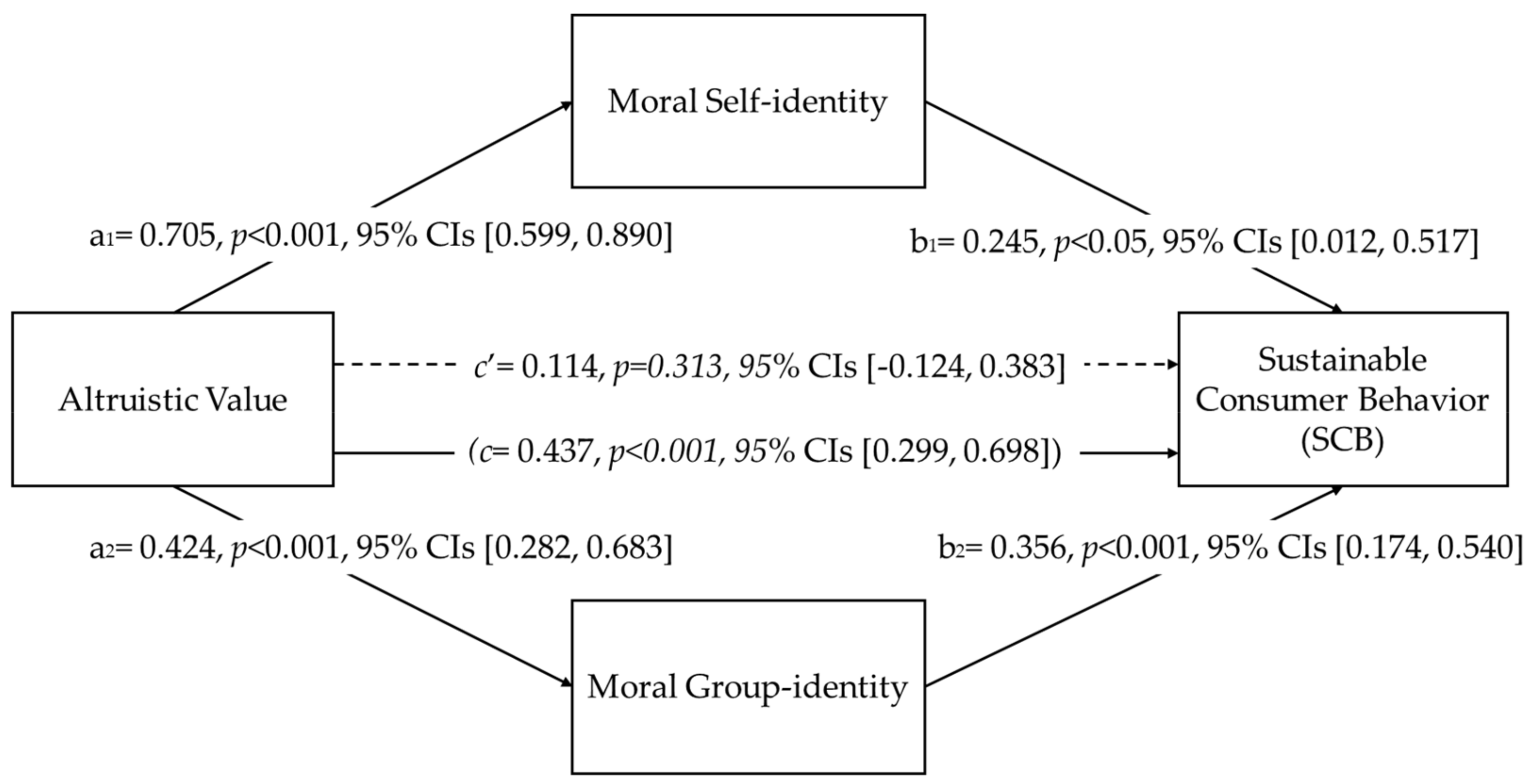

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Caveats and Future Research Directions

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bush, M.J. How to end the climate crisis. In Climate Change and Renewable Energy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 421–475. [Google Scholar]

- Udall. How I See Me: The Power of Identities for Encouraging Sustainable Actions, Bath Business and Society. Available online: https://blogs.bath.ac.uk/business-and-society/2020/05/01/how-i-see-me-the-power-of-identities-for-encouraging-sustainable-actions/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Nations, U. Home—United Nations Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Nations, U. COP26: Together for our planet|United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop26 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J.; Sukari, N.N. A multiple-item scale for measuring “sustainable consumption behaviour” construct: Development and psychometric evaluation. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesini, G.; Castiglioni, C.; Lozza, E. New trends and patterns in sustainable consumption: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulio, A.D.; Fischer, D.; Schäfer, M.; Blättel-Mink, B. Conceptualizing sustainable consumption: Toward an integrative framework. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2014, 10, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. Inside the sustainable consumption theoretical toolbox: Critical concepts for sustainability, consumption, and marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salciuviene, L.; Banytė, J.; Vilkas, M.; Dovalienė, A.; Gravelines, Ž. Moral identity and engagement in sustainable consumption. J. Consum. Mark. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udall, A.M.; de Groot, J.I.M.; de Jong, S.B.; Shankar, A. How do I see myself? A systematic review of identities in pro-environmental behaviour research. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 108–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinario, E.; Lorenzi, C.; Bartoccioni, F.; Perucchini, P.; Bobeth, S.; Colléony, A.; Diniz, R.; Eklund, A.; Jaeger, C.; Kibbe, A. From childhood nature experiences to adult pro-environmental behaviors: An explanatory model of sustainable food consumption. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1137–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, I.; Barth, M.; Jugert, P.; Masson, T.; Reese, G. A social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). Psychol. Rev. 2018, 125, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, S.; Klöckner, C.A.; Carrus, G.; Chokrai, P.; Fritsche, I.; Masson, T.; Panno, A.; Tiberio, L.; Udall, A.M. Donations to renewable energy projects: The role of social norms and donor anonymity. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 193, 107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; De Groot, J.I. Environmental Values; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vinzenz, F.; Priskin, J.; Wirth, W.; Ponnapureddy, S.; Ohnmacht, T. Marketing sustainable tourism: The role of value orientation, well-being and credibility. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1663–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survey, E.S. ESS Round 8 Source Questionnaire. Available online: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.html?r=8 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Verplanken, B.; Holland, R.W. Motivated decision making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Berger, J.; Menon, G. When identity marketing backfires: Consumer agency in identity expression. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoushy, S.; Lanzini, P. Factors affecting sustainable consumer behavior in the MENA region: A systematic review. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 33, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Fischer, D.; Schrader, U. Measuring what matters in sustainable consumption: An integrative framework for the selection of relevant behaviors. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinova, E. Sustainable consumer behavior: Literature overview. Econ. Altern. 2016, 2, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S. Sustainable development and consumption: The ambiguities-the Oslo ministerial roundtable conference on sustainable production and consumption, Oslo, 6–10 February 1995. Environ. Politics 1996, 5, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Raworth, K.; Rockström, J. Between Social and Planetary Boundaries: Navigating Pathways in the Safe and Just Space for Humanity; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Antonides, G. Sustainable consumer behaviour: A collection of empirical studies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piligrimienė, Ž.; Žukauskaitė, A.; Korzilius, H.; Banytė, J.; Dovalienė, A. Internal and external determinants of consumer engagement in sustainable consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Lei, Z.; Jia, H. Understanding the evolution of sustainable consumption research. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Markowitz, E. Sustainable consumer behavior: A multilevel perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, E.; Mont, O.; Power, K. A map is not a territory—Making research more helpful for sustainable consumption policy. J. Consum. Policy 2014, 37, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gatersleben, B.; Murtagh, N.; Abrahamse, W. Values, identity and pro-environmental behaviour. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2014, 9, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D. Identity-based motivation. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A.; White, K.M. The theory of planned behaviour: Self-identity, social identity and group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 38, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S.; Burke, P.J. The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronin, E. How we see ourselves and how we see others. Science 2008, 320, 1177–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udall, A.M.; de Groot, J.I.M.; De Jong, S.B.; Shankar, A. How I See Me-A Meta-Analysis Investigating the Association Between Identities and Pro-environmental Behaviour. Front. Psychol 2021, 12, 582421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Identity A Read. 1979, 56, 9780203505984-16. [Google Scholar]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Schubert, I.; Thøgersen, J. Morality and green consumer behaviour: A psychological perspective. In Ethics and Morality in Consumption; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yaprak, A.; Prince, M. Consumer morality and moral consumption behavior: Literature domains, current contributions, and future research questions. J. Consum. Mark. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, D.; Atkins, R.; Ford, D. Urban America as a context for the development of moral identity in adolescence. J. Soc. Issues 1998, 54, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Reed II, A. The self-importance of moral identity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Carlo, G. Moral identity. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 495–513. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Van der Werff, E.; Bouman, T.; Harder, M.K.; Steg, L. I Am vs. We Are: How Biospheric Values and Environmental Identity of Individuals and Groups Can Influence Pro-environmental Behaviour. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 618956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G.; Van der Werff, E.; Lurvink, J. The significance of hedonic values for environmentally relevant attitudes, preferences, and actions. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Steg, L. Motivating society-wide pro-environmental change. One Earth 2019, 1, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. The Role of Values, Environmental Self-Identity, Social Norms, and Intrinsic Motivations in Consumers’ Eco-Friendly Apparel Purchasing Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ruepert, A.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L.; Maricchiolo, F.; Carrus, G.; Dumitru, A.; Mira, R.G.; Stancu, A.; Moza, D. Environmental considerations in the organizational context: A pathway to pro-environmental behaviour at work. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 17, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MediaSmarts. Advertising: It’s Everywhere|MediaSmarts. Available online: https://mediasmarts.ca/marketing-consumerism/advertising-its-everywhere (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Yurteri, S. Effects of Brand Priming on Sustainable Consumption Attitudes and Behaviors. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Çankaya/Ankara, Turkey, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Išoraitė, M. Marketing mix theoretical aspects. Int. J. Res. -Granthaalayah 2016, 4, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-K.; Wu, W.-Y.; Pham, T.-T. Examining the moderating effects of green marketing and green psychological benefits on customers’ green attitude, value and purchase intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Ashfaq, M.; Begum, S.; Ali, A. How “Green” thinking and altruism translate into purchasing intentions for electronics products: The intrinsic-extrinsic motivation mechanism. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, C. Gratifications for using social media: A comparative analysis of Sina Weibo and WeChat in China. Inf. Dev. 2018, 34, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, A.; Hofmann, S.G. Why do people use Facebook? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Is n = 30 Really Enough? A Popular Inductive Fallacy among Data Analysts.|by Abhibhav Sharma|Towards Data Science. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/is-n-30-really-enough-a-popular-inductive-fallacy-among-data-analysts-95661669dd98 (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Guo, C.; Shim, J.; Otondo, R. Social network services in China: An integrated model of centrality, trust, and technology acceptance. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 13, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.H.; Cao, Y. Examining WeChat users’ motivations, trust, attitudes, and positive word-of-mouth: Evidence from China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 41, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- khandelwal, M. Likert Scale: Whats, Whys, Hows & Everything to know in 2022. Available online: https://www.surveysensum.com/blog/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-likert-scale/#:~:text=b)%207%2Dpoint%20Likert%20Scale,neutral%20opinion%20to%20the%20respondents (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Sudbury-Riley, L.; Kohlbacher, F. Ethically minded consumer behavior: Scale review, development, and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2697–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Steg, L.; Kiers, H.A. Measuring values in environmental research: A test of an environmental portrait value questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.J.; Winterich, K.P. Can brands move in from the outside? How moral identity enhances out-group brand attitudes. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewski, C.; Wyer Jr, R.S. Content and process priming: A review. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesterberg, T. Bootstrap. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 497–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, D.K.; Zickar, M.J. Some common myths about centering predictor variables in moderated multiple regression and polynomial regression. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 15, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-K. Doing good better: Impure altruism in green apparel advertising. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, M.D.; Cieciuch, J.; Duriez, B.; Soenens, B. The how and what of identity formation: Associations between identity styles and value orientations. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T.; Victor, R. Why be moral? Moral identity motivation and age. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford university press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1957; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sriram, V.; Forman, A.M. The relative importance of products′ environmental attributes: A cross-cultural comparison. Int. Mark. Rev. 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, A.; Dahlstrand, U.; Grankvist, G. Habitual and value-guided purchase behavior. Ambio A J. Hum. Environ. 2005, 34, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B. Promoting sustainability: Towards a segmentation model of individual and household behaviour and behaviour change. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L.C. Values and proenvironmental behavior: A five-country survey. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1998, 29, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-K. A human-centered approach to green apparel advertising: Decision tree predictive modeling of consumer choice. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, K.L.; Häubl, G. The signature effect: Signing influences consumption-related behavior by priming self-identity. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.-W.; Udall, A.M.; Tam, K.-P. Effects of perceived social norms on support for renewable energy transition: Moderation by national culture and environmental risks. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Promoting sustainable consumption behaviors: The impacts of environmental attitudes and governance in a cross-national context. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 1128–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, J.; Reinders, M.J. Consuming apart, together: The role of multiple identities in sustainable behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypotheses (H) | Evidence | Positive or Negative Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| H1a: Altruistic values predict moral self-identities | ✔ | Positive |

| H2b: Altruistic values predict moral group-identities | X | Positive |

| H2a: Moral self-identity predicts SCB | X | Positive |

| H2b: Moral group-identity predicts SCB | X | Positive |

| H3a: Altruistic values predict SCB | ✔ | Positive |

| H3b: Moral self- and group-identity mediate the relationship between altruistic values and SCB | X | NA |

| H4: Promotion has a moderation effect on the relationship between altruistic values and SCB | X | Unknown |

| Moral Self-Identity | Moral Group-Identity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | Sig. | R2 | β | t | Sig. | R2 | |

| Altruistic Values | 0.705 | 10.141 | <0.001 | 0.497 | 0.424 | 4.771 | <0.001 | 0.180 |

| SCB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | Sig. | R2 | |

| Moral self-identity | 0.320 | 3.488 | <0.01 | 0.355 |

| Moral group-identity | 0.367 | 4.002 | <0.001 | |

| SCB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | Sig. | R2 | |

| Altruistic Values | 0.437 | 4.959 | <0.001 | 0.191 |

| All Participants (n = 106) | High Altruistic Values Participants (n = 95) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | Sig. | R2 | β | t | Sig. | R2 | |

| Centered altruistic values | 0.262 | 2.458 | 0.016 | 0.264 | 0.025 | 0.175 | 0.861 | 0.215 |

| Promotion | 0.211 | 2.394 | 0.019 | 0.192 | 1.958 | 0.053 | ||

| Interaction item | 0.204 | 1.950 | 0.054 | 0.358 | 2.419 | 0.018 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Udall, A.M. Sustainable Consumer Behaviors: The Effects of Identity, Environment Value and Marketing Promotion. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021129

Wang B, Udall AM. Sustainable Consumer Behaviors: The Effects of Identity, Environment Value and Marketing Promotion. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021129

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bei, and Alina M. Udall. 2023. "Sustainable Consumer Behaviors: The Effects of Identity, Environment Value and Marketing Promotion" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021129

APA StyleWang, B., & Udall, A. M. (2023). Sustainable Consumer Behaviors: The Effects of Identity, Environment Value and Marketing Promotion. Sustainability, 15(2), 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021129