Creating Shared Value in Banking by Offering Entrepreneurship Education to Female Entrepreneurs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Banking and Female Entrepreneurship

2.2. Entrepreneurship Education

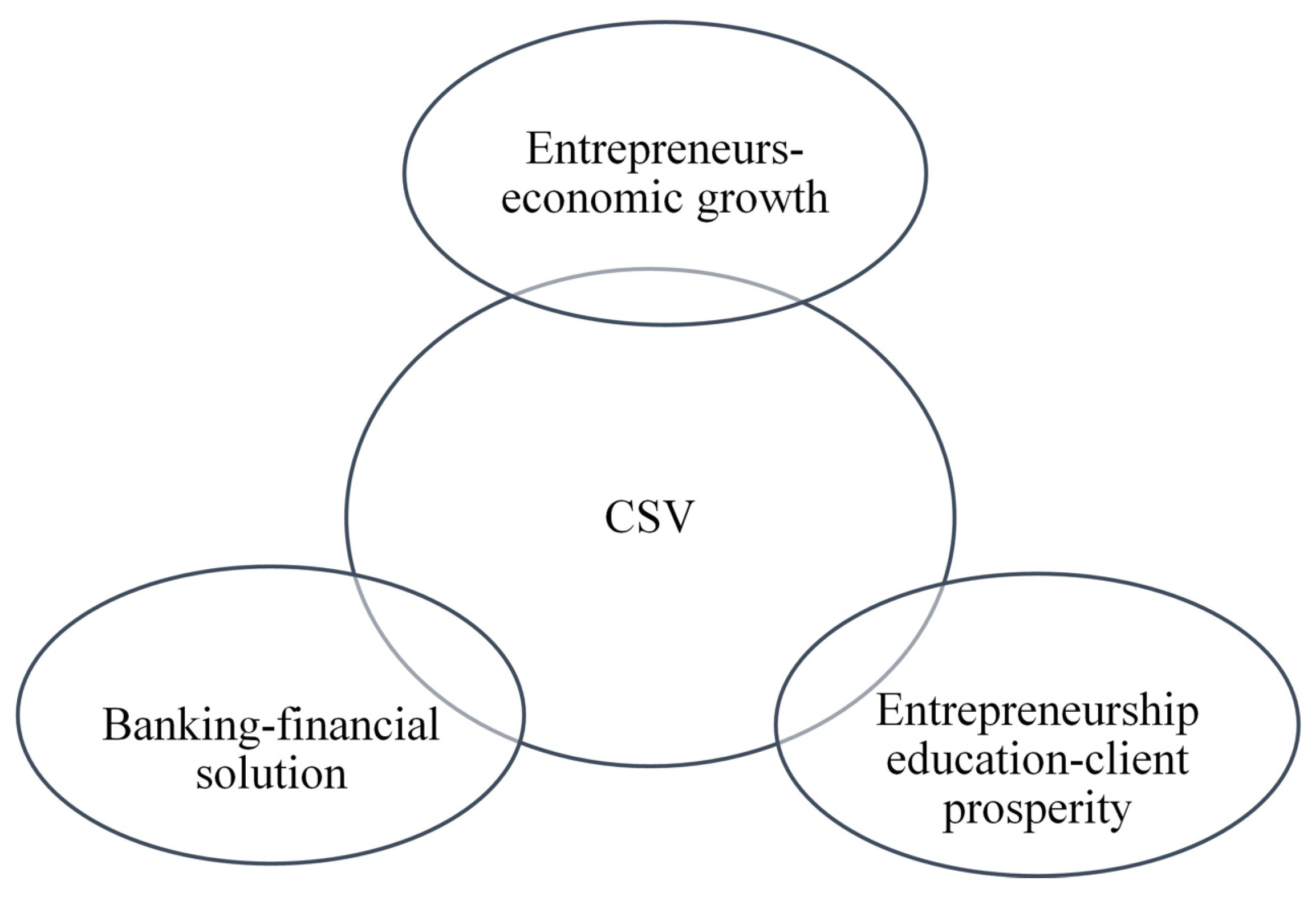

2.3. Creating Shared Value

2.4. Using Creating Shared Value

3. Methodology

3.1. Strategy

3.2. Case Organization

3.3. Interview Participants and Data Collection

4. Analysis

5. Findings of Case Analysis

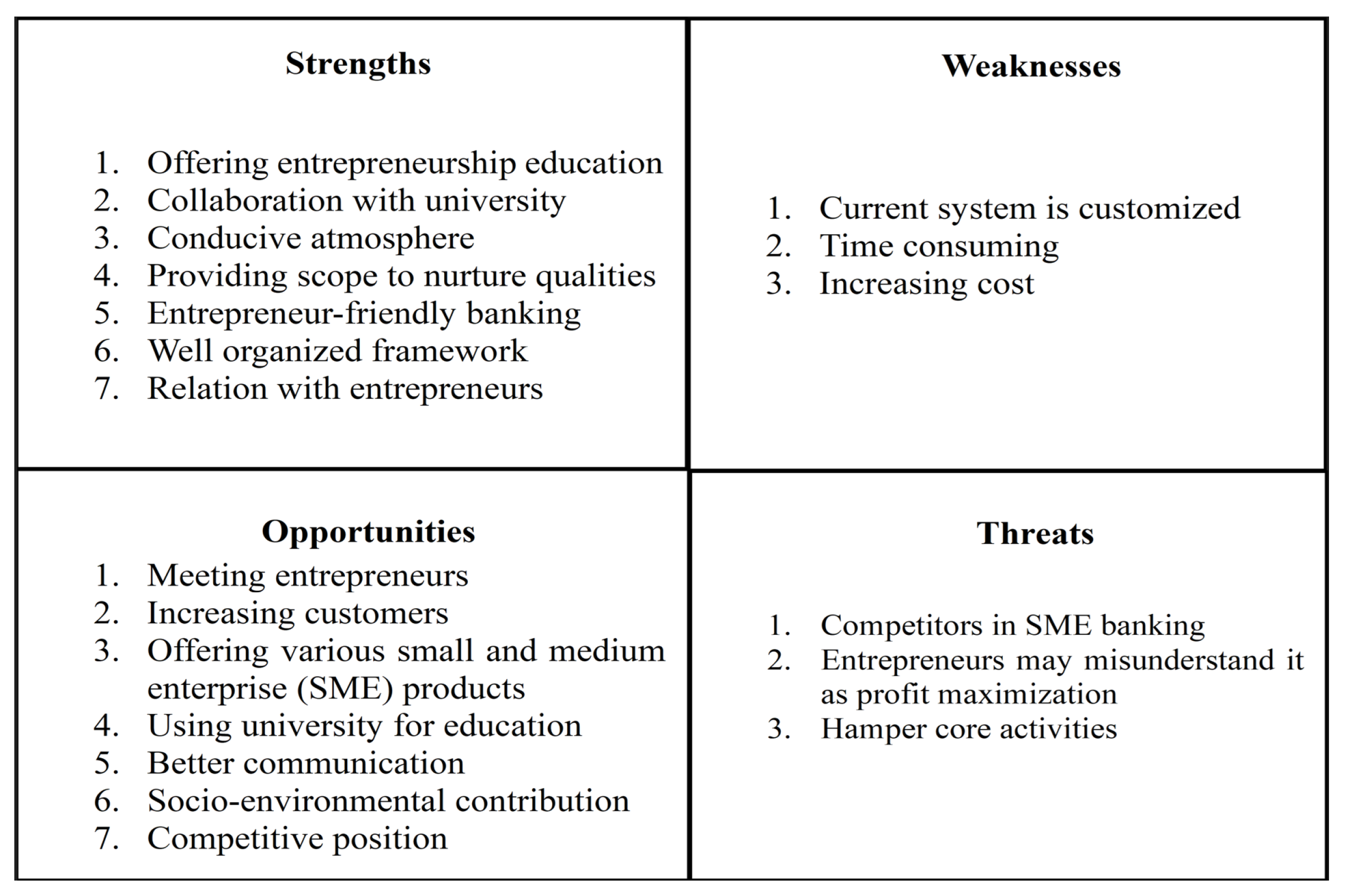

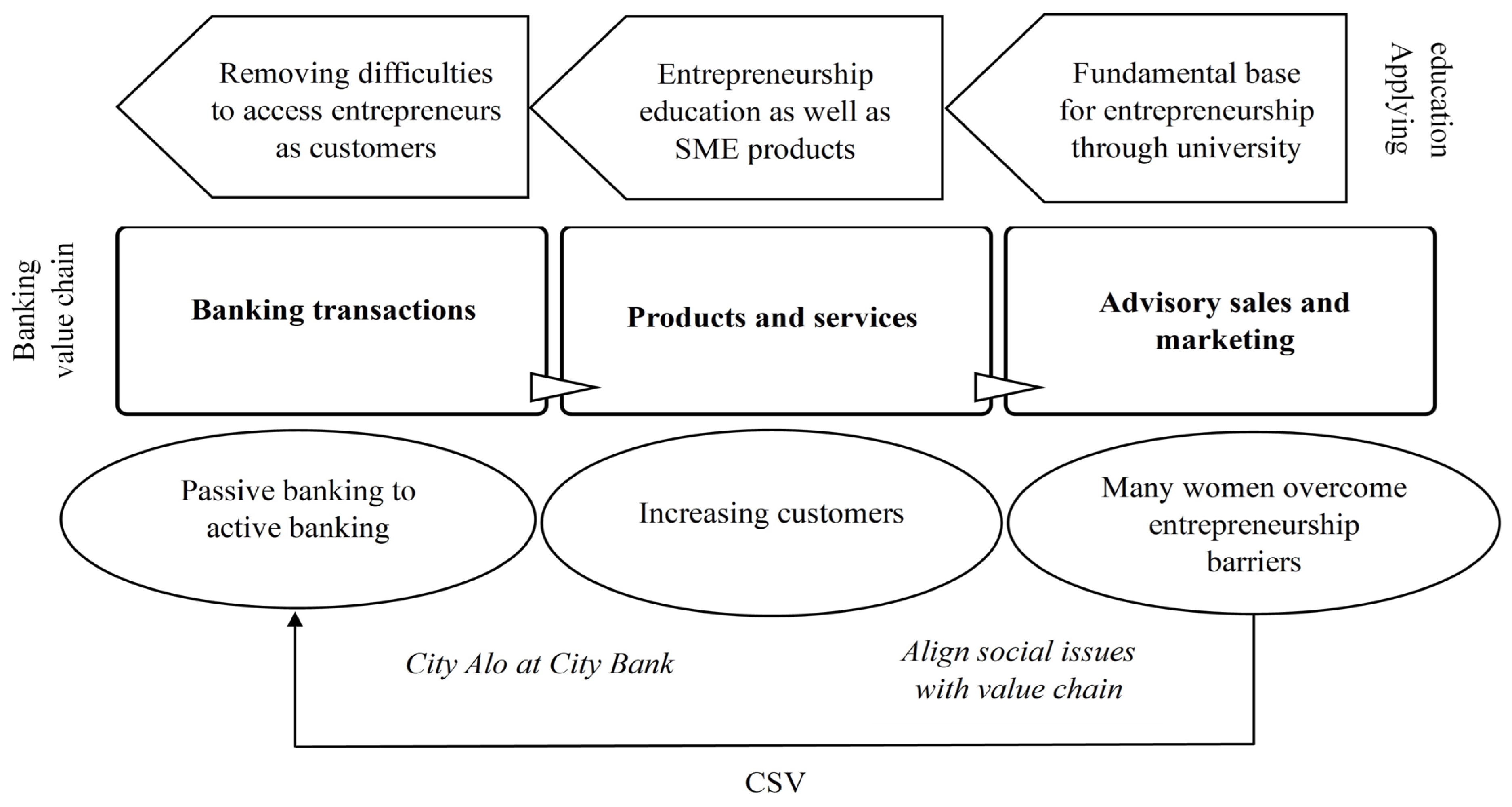

5.1. Considering Entrepreneurs by Banking

Entrepreneurs are heading in the same direction, so special criteria are necessary to secure a good self-employed career […]. Most of the funding is covered by the bank and the rest is charged to the entrepreneurs as course fees. Our bank determines social problems, thinks of solutions, and converts those solutions into a business […].[City Alo official: interviewee 1]

5.2. Providing Entrepreneurship Education

There is a scope to understanding and consulting about one’s limitations […]. Gaining capabilities enables us to find challenges and solutions. By analyzing […] risks and problems through entrepreneurship education, we find possible real-business solutions to start and survive as a business.[Entrepreneur: clothing]

5.3. Developmental Qualities for Entrepreneurship

5.4. Banking Business Transforms from Traditional to Socially Responsible

My identity became stronger as an entrepreneur, and I have enough savings and investment, etc. By creating scope in income-generating activities, I have an independent and self-motivated career. I am financially solvent and can run the business in a better way […].[Entrepreneur: export/import]

We targeted all types of prospective women; service holders, housewives, professionals, and established entrepreneurs […]. City Alo offers an educational environment where they can talk in a friendly atmosphere to think more about entrepreneurship […]. So, by prioritizing women entrepreneurs, the bank has targeted […] to reach society and to become more profitable.[City Alo official: interviewee 2]

5.5. Creating Shared Value for Banking

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Concluding Remarks

6.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value. How to reinvent capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Menghwar, P.S.; Daood, A. Creating shared value: A systematic review, synthesis and integrative perspective. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockstette, V.; Pfitzer, M.; Smith, D.; Bhavaraju, N.; Priestley, C.; Bhatt, A. Banking on Shared Value: How Banks Profit by Rethinking Their Purpose; FSG: Austin, TX, USA, 2014; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ilmarinen, P. Creating shared value in the banking industry: A case study from Finland. Finn. Bus. Rev. 2018, 1–10. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/152312 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Durkin, M.; McGowan, P.; Babb, C. Banking support for entrepreneurial new venturers: Toward greater mutual understanding. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2013, 20, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamboulis, Y.; Barlas, A. Entrepreneurship education impact on student attitudes. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, K.M.; Gielnik, M.M.; Frese, M. When capital does not matter: How entrepreneurship training buffers the negative effect of capital constraints on business creation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2020, 14, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahta, D.; Yun, J.; Islam, M.R.; Ashfaq, M. Corporate social responsibility, innovation capability and firm performance: Evidence from SME. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 840–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, A.; De Luque, M.S.; Abdelzaher, D.; Heim, W. Developing women leaders through entrepreneurship education and training. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 29, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, R.K. Measuring the impact of business management Student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Comput. Human Behav. 2020, 107, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwobobia, F.M. The Challenges Facing Small-Scale Women Entrepreneurs: A Case of Kenya. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2012, 3, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Guha, R.; Malkar, N.; Pandey, N. Marching Towards Creating Shared Value: The Case of YES Bank. Asian Case Res. J. 2019, 23, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhim, R.; Lubis, A.W.; Faradynawati, I.A.A.; Perdana, W.A.; Deni Yonathan, A. Examining the role of microfinance: A creating shared value perspective. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2023, 39, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Hossain, S.Z. Conceptual mapping of shared value creation by the private commercial banks in Bangladesh. Asian J. Sustain. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, M.; Haeruddin, M.; Azis, F. Entrepreneurship Education and Career Intention: The Perks of being a Woman Student. J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Salavou, H.E.; Chalkos, G.; Lioukas, S. Linkages between entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurship education: New evidence on the gender imbalance. Educ. Train. 2021, 63, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrus, S.; Pauzi, N.M.; Munir, Z.A. The Effectiveness of Training Model for Women Entrepreneurship Program. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 129, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, D.; Smith, K.; Mirza, M. Entrepreneurial Education: Reflexive Approaches to Entrepreneurial Learning in Practice. J. Entrep. 2013, 22, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Chandran, V.G.R.; Klobas, J.E.; Liñán, F.; Kokkalis, P. Entrepreneurship education programmes: How learning, inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeinat, I.M.; Abdulfatah, F.H. Organizational culture and knowledge management processes: Case study in a public university. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2019, 49, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenurm, T.; Reino, A. Knowledge sharing challenges in developing early-stage entrepreneurship. In European Conference on Knowledge Management; Janiunaite, B., Petraite, M., Eds.; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Weerakoon, C.; McMurray, A.J.; Rametse, N.; Arenius, P. Knowledge creation theory of entrepreneurial orientation in social enterprises. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 834–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.; Dwyer, K.; Gray, B. Students’ reflections on the value of an entrepreneurship education. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrialgo, M.; Iglesias, V. The moderating role of entrepreneurship education on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 1209–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P.; Solesvik, M.Z. Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: Do female students benefit? Int. small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 979–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.H. The effects of creating shared value (CSV) on the consumer self–brand connection: Perspective of sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.; Lee, S.; Yoon, H.; Kim, C. Linking creating shared value to customer behaviors in the food service context. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awale, R.; Rowlinson, S. A conceptual framework for achieving firm competitiveness in construction: A “Creating Shared Value” (CSV) concept. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Association of Researchers in Construction Management Conference, ARCOM 2014, Portsmouth, UK, 1–3 September 2014; Raiden, A.B., Aboagye-Nimo, E., Eds.; Association of Researchers in Construction Management: Portsmouth, UK, 2014; pp. 1285–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the value of “creating shared value”. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Na, Y.K. Effects of strategy characteristics for sustainable competitive advantage in sharing economy businesses on creating shared value and performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.C.; Saito, A.; Avvari, V.M. Interpretation and integration of “creating shared value” in Asia: Implications for strategy research and practice. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 19, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J. Creating shared value as a business strategy for mining to advance the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Y. From Participation to Consumption: The Role of Self-Concept in Creating Shared Values Among Sport Consumers. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Biscaia, R.; Papadas, K.; Simkin, L.; Carter, L. The creation of shared value in the major sport event ecosystem: Understanding the role of sponsors and hosts. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2023, 23, 811–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, C. Creating shared value strategies to reach the United Nations sustainable development goals: Evidence from the mining industry. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 14, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanli, N.; Williamson, J. Minimizing the sustainability knowledge-practice gap through creating shared value: The case of small accommodation firms. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.K.; Yan, M.R. The corporate shared value for sustainable development: An ecosystem perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamond, M.T.; Bond, C.J.; Ripley, M. How HR from Multinationals Assist in Creating Shared Values in Emerging Economies: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 2023, p. 17032. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.R.R.; Hung-Baesecke, C.J.F.; Bowen, S.A.; Zerfass, A.; Stacks, D.W.; Boyd, B. The role of leadership in shared value creation from the public’s perspective: A multi-continental study. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.O. How CSV and CSR affect organizational performance: A productive behavior perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggun, M.; Sari, J.; Fitriyani, N.A.; Hartojo, H. Implementation of Creating Shared Value (CSV) in the Community Empowerment Program “Cardamom Spice Village” PT Industri Jamu dan Farmasi Sido Muncul Tbk. Prospect. J. Pemberdaya. Masy. 2023, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H.J. Social value in public enterprises from the perspective of Creating Shared Value (CSV): The case of the Korea Expressway Corporation. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2022, 88, 1211–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, H.; Snell, R.S. Examining mechanisms for creating shared value by Asian firms. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier de Leth, D.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F. Creating Shared Value Through an Inclusive Development Lens: A Case Study of a CSV Strategy in Ghana’s Cocoa Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas Lizama, J.; Royo-Vela, M. Implementation and measurement of shared value creation strategies: Proposal of a conceptual model. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Discovering the future of the case study. Method in evaluation research. Eval. Pract. 1994, 15, 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Revised and Expanded from “Case Study Research in Education”; ERIC: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 0787910090. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 41, ISBN 1452285837. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Grenier, R.S. Qualitative Research in Practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; ISBN 1119452023. [Google Scholar]

- de Marrais, K.B.; Lapan, S.D. Qualitative interview studies: Learning through experience. In Foundations for Research; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2003; pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 1529755999. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Applied thematic analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 154436721X. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, C. Qualitative Analysis Using MAXQDA: The Five-Level QDA® Method; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; ISBN 1315268566. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Role of Business in Prosperity: Only Business Can Create Prosperity. In The Future of Corporate Citizenship: Creating Shared Value; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The new competitive advantage: Creating shared value. In Proceedings of the Presentation at the HSM World Business Forum CSV, New York, NY, USA, 3 October 2012; Volume 21, p. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, S. Constraints faced by women entrepreneurs in developing countries: Review and ranking. Gend. Manag. 2018, 33, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggadwita, G.; Dhewanto, W. The influence of personal attitude and social perception on women entrepreneurial intentions in micro and small enterprises in Indonesia. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2016, 27, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Lawrence, A.T.; Porter, M.; Weber, J.; Kramer, M. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ketprapakorn, N.; Kantabutra, S. Culture development for sustainable SMEs: Toward a behavioral theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S.D.; Dew, N.; Venkataraman, S. Shaping Entrepreneurship Research; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Akehurst, G.; Simarro, E.; Mas-Tur, A. Women entrepreneurship in small service firms: Motivations, barriers and performance. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 2489–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Agarwal, N.; Brem, A. Women entrepreneurs as agents of change: A comparative analysis of social entrepreneurship processes in emerging markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 157, 120067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudhumbu, N.; du Plessis, E.C.; Maphosa, C. Challenges and opportunities for women entrepreneurs in Botswana: Revisiting the role of entrepreneurship education. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2020, 13, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véras, E.Z. Female Entrepreneurship: From Women’s Empowerment to Shared Value Creation. J. Innov. Sustain. RISUS 2015, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, N.; Sobel, R.S. Entrepreneurship, fear of failure, and economic policy. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2021, 66, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, P.H.; Neves, S.M.; Sant’Anna, D.O.; de Oliveira, C.H.; Carvalho, H.D. The analytic hierarchy process supporting decision making for sustainable development: An overview of applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Brownell, K.M.; Adams, J. What makes an entrepreneurship study entrepreneurial? Toward a unified theory of entrepreneurial agency. Entrep. theory Pract. 2021, 45, 1197–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Wright, M. Understanding the Social Role of Entrepreneurship. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) City Alo Enrolled-Entrepreneurs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | No. of Entrepreneurs | Age | Background | Education | |

| Catering | 2 | 34 | Private service | Bachelor | |

| 28 | Teacher | Masters | |||

| Clothing | 2 | 24 | Student | BBA | |

| 32 | Housewife | Bachelor | |||

| Bakery | 2 | 33 | Private service | Masters | |

| 27 | Student | Masters | |||

| Dry fish | 2 | 30 | Entrepreneur | Bachelor | |

| 32 | Govt service | MBA | |||

| Home decor | 2 | 23 | Student | Higher secondary | |

| 35 | Teacher | Masters | |||

| Jewellery | 2 | 40 | Housewife | Bachelor | |

| 28 | Call center | Higher secondary | |||

| Training and fitness | 2 | 30 | Student | Masters | |

| 42 | Entrepreneur | Bachelor | |||

| Event management | 2 | 22 | Entrepreneur | Bachelor | |

| 26 | Private service | Masters | |||

| Export/import | 2 | 45 | Family business | Higher secondary | |

| 38 | Freelancer | Bachelor | |||

| Consultancy | 2 | 25 | Student | Masters | |

| 32 | accountant or chartered accountant | CA | |||

| Total | 20 | ||||

| (b) City Alo Officials | |||||

| Division | Location | Position | No. | Age | Education |

| City Alo: Dhaka | Head office, Gulshan | Retail banker | 2 | 35 | MBA |

| 32 | Masters | ||||

| City Alo officer | 2 | 28 | Masters | ||

| 30 | MBA | ||||

| SME banker | 1 | 40 | Masters | ||

| City Alo: Chittagong | Branch office, Agrabad | Retail banker | 1 | 38 | MBA |

| City Alo officer | 2 | 27 | MBA | ||

| 36 | Masters | ||||

| Total | 8 | ||||

| Successful | No | Moderately Successful | No | Not Successful | No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catering | 2 | Jewellery | 1 | Training and fitness | 1 |

| Clothing | 2 | Consultancy | 1 | Jewellery | 1 |

| Bakery | 1 | Dry fish | 2 | ||

| Export/import | 2 | Bakery | 1 | ||

| Consultancy | 1 | ||||

| Home decor | 2 | ||||

| Event management | 2 | ||||

| Training and fitness | 1 | ||||

| Total = 20 | 13 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Percentage = 100% | 65% | 25% | 10% |

| Pillar | Achieving CSV | Creating Social Value | Creating Economic Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | CSV is a strategic process, not one-time activity | CSV is a strategic process, not only a one-time activity. City Bank added entrepreneurship education as a program in the value chain rather than considering it as a one-time activity. | By offering entrepreneurship education, the value chain of City Bank ensures long-term benefits. This framework is related to regular business functions, which are aimed at increasing the bank’s competitive advantage. |

| 2. | Social issues related to value chain | The City Alo case places importance on entrepreneurs and maintains relations between key entrepreneurs and the small and medium enterprise (SME) function of the bank. | The City Alo case added ideas within the banking so that it helps in aiding target customers, reallocating resources, and maximizing profit. |

| 3. | Economic yield in terms of profit | City Alo female banking provides developmental support and information on small and medium enterprise resources and products so that people can become successful entrepreneurs. | Entrepreneurs as customers come to the bank to receive entrepreneurship support, so it becomes a means of increasing customers for the bank. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taskin, S.; Javed, A.; Kohda, Y. Creating Shared Value in Banking by Offering Entrepreneurship Education to Female Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914475

Taskin S, Javed A, Kohda Y. Creating Shared Value in Banking by Offering Entrepreneurship Education to Female Entrepreneurs. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914475

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaskin, Sharmin, Amna Javed, and Youji Kohda. 2023. "Creating Shared Value in Banking by Offering Entrepreneurship Education to Female Entrepreneurs" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914475

APA StyleTaskin, S., Javed, A., & Kohda, Y. (2023). Creating Shared Value in Banking by Offering Entrepreneurship Education to Female Entrepreneurs. Sustainability, 15(19), 14475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914475