Mitigating the Impact of Work Overload on Cybersecurity Behavior: The Moderating Influence of Corporate Ethics—A Mediated Moderation Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

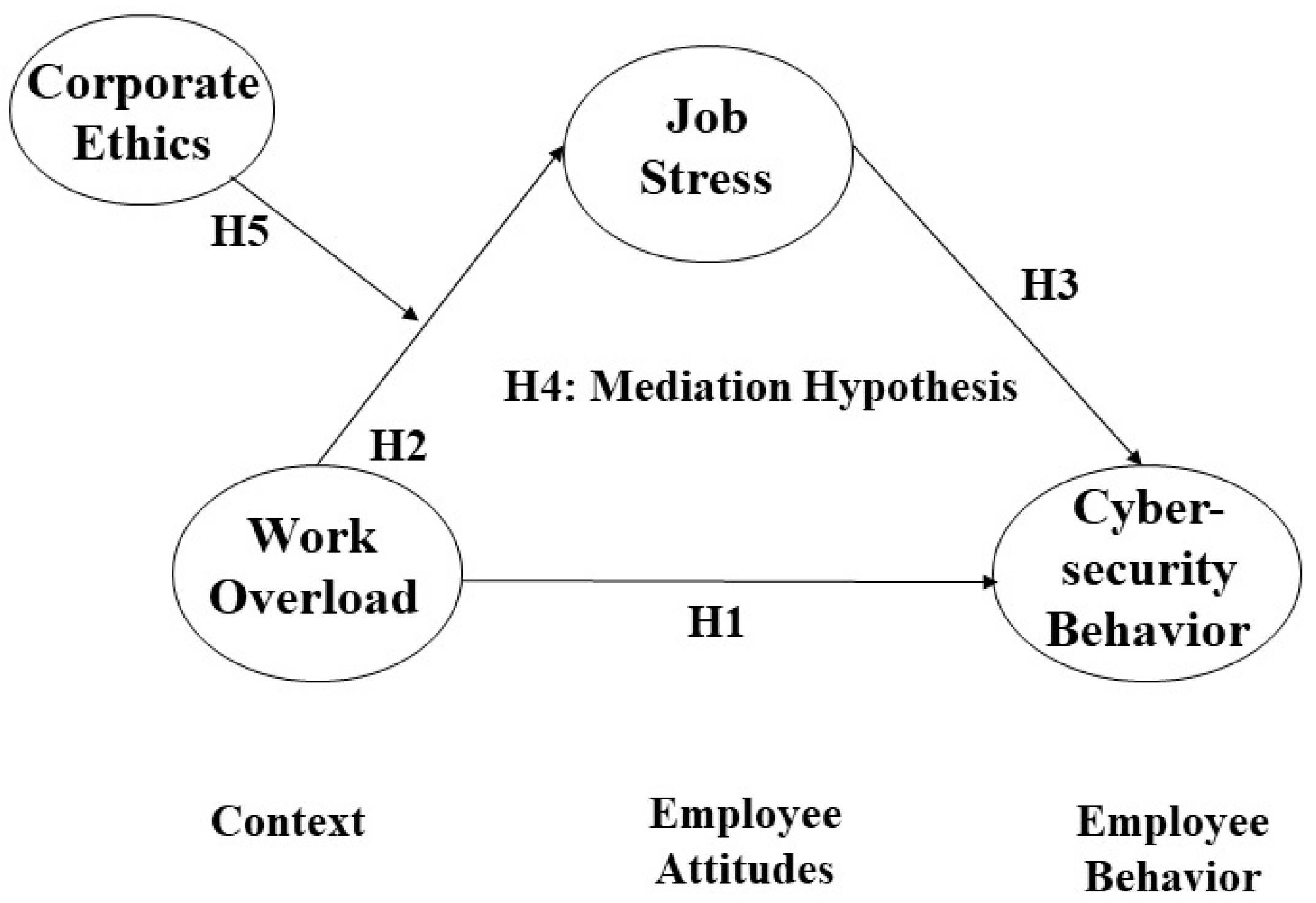

- Investigate the relationship between work overload and cyber security behavior among employees.

- Examine job stress as a mediating variable in this relationship.

- Explore the moderating effect of organizational ethics on the relationship between work overload and job stress.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Work Overload and Cybersecurity Behavior

2.2. Work Overload and Job Stress

2.3. Job Stress and Cybersecurity Behavior

2.4. Job Stress and Work Overload–Cybersecurity Behavior

2.5. Corporate Ethics and Work Overload–Job Stress

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Work Overload (Time Point 1)

3.2.2. Corporate Ethics (Time Point 1)

3.2.3. Job Stress (Time Point 2)

3.2.4. Cybersecurity Behavior (Time Point 3)

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Data Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

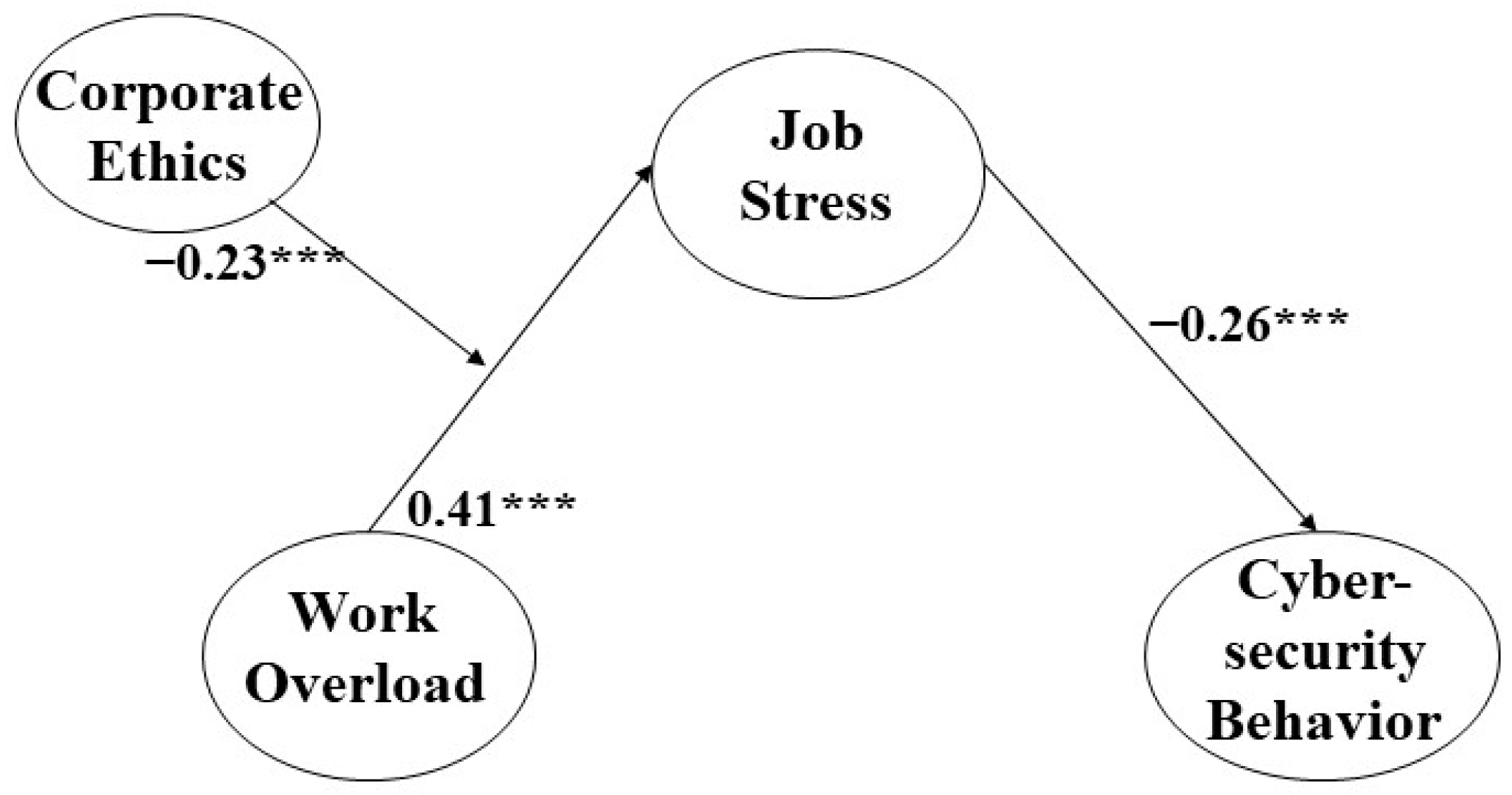

4.3. Structural Model

4.3.1. Results of the Mediation Analysis

4.3.2. Bootstrapping

4.3.3. Result of Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sergent, K.; Stajkovic, A.D. Women’s leadership is associated with fewer deaths during the COVID-19 crisis: Quantitative and qualitative analyses of United States governors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Straub, C. Flexible employment relationships and careers in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, R.D.; Jones, K.W. Effects of work load, role ambiguity, and Type A personality on anxiety, depression, and heart rate. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, J.C.; Marshall, D.R.; Michaelis, T.L.; Pollack, J.M.; Sheats, L. The role of work-to-venture role conflict on hybrid entrepreneurs’ transition into entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 2302–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Euwema, M.C. Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhango, M.; Dzobo, M.; Chitungo, I.; Dzinamarira, T. COVID-19 risk factors among health workers: A rapid review. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Hansiya Abdul Rauf, F.; Rathnasekara, H. Working to help or helping to work? Work-overload and allocentrism as predictors of organizational citizenship behaviours. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 2807–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga Medina, H.R.; Campoverde Aguirre, R.; Coello-Montecel, D.; Ochoa Pacheco, P.; Paredes-Aguirre, M.I. The influence of work–family conflict on burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effect of teleworking overload. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odes, R.; Hong, O. Job Stress and Sleep Disturbances among Career Firefighters in Northern California. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 68, 706–710. [Google Scholar]

- Hon, A.H.; Kim, T.Y. Work overload and employee creativity: The roles of goal commitment, task feedback from supervisor, and reward for competence. Curr. Top. Manag. 2018, 12, 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Izdebski, Z.; Kozakiewicz, A.; Białorudzki, M.; Dec-Pietrowska, J.; Mazur, J. Occupational burnout in healthcare workers, stress and other symptoms of work overload during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmieciak, R. Knowledge-withholding behaviours among IT specialists: The roles of job insecurity, work overload and supervisor support. J. Manag. Organ. 2023, 29, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.S.; Kim, B.J. “The Power of a Firm’s Benevolent Act”: The Influence of Work Overload on Turnover Intention, the Mediating Role of Meaningfulness of Work and the Moderating Effect of CSR Activities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Molino, M.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Workload, techno overload, and behavioral stress during COVID-19 emergency: The role of job crafting in remote workers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval-Reyes, J.; Acosta-Prado, J.C.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C. Relationship amongst technology use, work overload, and psychological detachment from work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, Z.; Li, B.; Li, Q.; London, M.; Yang, B. The double-edged sword of coaching: Relationships between managers’ coaching and their feelings of personal accomplishment and role overload. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2019, 30, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Robledo, E.; Vignoli, M.; Topa, G.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work engagement: A meta-analysis using the job demands-resources model. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 1069–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.H.N. Exploring relationships among overload stress, work-family conflict, job satisfaction, person–organisation fit and organisational commitment in public organizations. Public Organ. Rev. 2023, 23, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, B.; Antoni, C.H. Drowning in the flood of information: A meta-analysis on the relation between information overload, behaviour, experience, and health and moderating factors. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2023, 32, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, N.; Yang, C.; Han, L.; Jou, M. Too much overload and concerns: Antecedents of social media fatigue and the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Jex, S.M. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.F.; Yaqoob, A.; Khan, M.S.; Ikram, N. The cybersecurity behavioral research: A tertiary study. Comput. Secur. 2023, 120, 102826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, M.; Freeman, M.; Tootell, H. Exploring the factors that influence the cybersecurity behaviors of young adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 136, 107376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharida, R.A.; Al-rimy, B.A.S.; Al-Emran, M.; Zainal, A. A systematic review of multi perspectives on human cybersecurity behavior. Technol. Soc. 2023, 73, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansoori, A.; Al-Emran, M.; Shaalan, K. Exploring the Frontiers of Cybersecurity Behavior: A Systematic Review of Studies and Theories. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannelønning, K.; Katsikas, S.K. A Systematic literature review of how cybersecurity-related behavior has been assessed. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.F.; Ikram, N.; Murtaza, H.; Javed, M. Evaluating protection motivation based cybersecurity awareness training on Kirkpatrick’s Model. Comput. Secur. 2023, 125, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Kim, D. Pathways to cybersecurity awareness and protection behaviors in South Korea. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2023, 63, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammaers, E. Theorizing discursive resistance to organizational ethics of care through a multi-stakeholder perspective on disability inclusion practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 183, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Stress at Work; Publication Number 99–101; NIOSH: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lahti, H.; Kalakoski, V. Work stressors and their controllability: Content analysis of employee perceptions of hindrances to the flow of work in the health care sector. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Z.; Haghshenas, L.; Asghari, M.; Teimori, G.; Abedinloo, R. Relationship between Job Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Related Factors among Health Center Employees. J. Occup. Hyg. Eng. 2023, 9, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, C.; Gilbreath, B. Measuring Presenteeism from Work Stress: The Job Stress-Related Presenteeism Scale. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 65, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muyidi, A.; Zhang, Y.B.; Gist-Mackey, A. The influence of gender discrimination, supervisor support, and government support on Saudi female journalists’ job stress and satisfaction. Manag. Commun. Q. 2023, 37, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, G.; Warraich, N.F.; Iftikhar, S. Digital information security management policy in academic libraries: A systematic review (2010–2022). J. Inf. Sci. 2023, 01655515231160026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempestini, G.; Rovira, E.; Pyke, A.; Di Nocera, F. The Cybersecurity Awareness INventory (CAIN): Early Phases of Development of a Tool for Assessing Cybersecurity Knowledge Based on the ISO/IEC 27032. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2023, 3, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioskli, K.; Fotis, T.; Nifakos, S.; Mouratidis, H. The Importance of Conceptualising the Human-Centric Approach in Maintaining and Promoting Cybersecurity-Hygiene in Healthcare 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlangu, G.; Chipfumbu Kangara, C.; Masunda, F. Citizen-centric cybersecurity model for promoting good cybersecurity behaviour. J. Cyber Secur. Technol. 2023, 7, 154–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, K.; Dupuis, M. Cybersecurity insights gleaned from world religions. Comput. Secur. 2023, 132, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kävrestad, J.; Furnell, S.; Nohlberg, M. User perception of Context-Based Micro-Training–a method for cybersecurity training. Inf. Secur. J. A Glob. Perspect. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Haq, I.U.; Azeem, M.U. Gossiping about outsiders: How time-related work stress among collectivistic employees hinders job performance. J. Manag. Organ. 2023, 29, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madnick, B.; Huang, K.; Madnick, S. The evolution of global cybersecurity norms in the digital age: A longitudinal study of the cybersecurity norm development process. Inf. Secur. J. A Glob. Perspect. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, I.; Bahari, M. A complementary SEM and deep ANN approach to predict the adoption of cryptocurrencies from the perspective of cybersecurity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Demerouti, E. How does chronic burnout affect dealing with weekly job demands? A test of central propositions in JD-R and COR-theories. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, L.; Wu, D. The influence of grit on nurse job satisfaction: Mediating effects of perceived stress and moderating effects of optimism. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1094031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, M.; Sattler, S.; Reimann, M. Towards an understanding of how stress and resources affect the nonmedical use of prescription drugs for performance enhancement among employees. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 4784–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, S.L.; Murphy, L.R.; Hurrell, J.J. Prevention of work-related psychological disorders: A national strategy proposed by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgio, A.; Barattucci, M.; Teresi, M.; Raulli, G.; Ballone, C.; Ramaci, T.; Pagliaro, S. Organizational identification as a trigger for personal well-being: Associations with happiness and stress through job outcomes. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 33, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elomaa, M.; Eskelä-Haapanen, S.; Pakarinen, E.; Halttunen, L.; Lerkkanen, M.K. Work-related stress of elementary school principals in Finland: Coping strategies and support. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2023, 51, 868–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauno, S.; Herttalampi, M.; Minkkinen, J.; Feldt, T.; Kubicek, B. Is work intensification bad for employees? A review of outcomes for employees over the last two decades. Work Stress 2023, 37, 100–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, M.; Fagan, A.A. The effects of victimization on offending: An examination of General Strain Theory, criminal propensity, risk, protection, and resilience. Vict. Offenders 2023, 18, 1009–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Leban, L.; Lee, Y.; Jennings, W.G. Testing gender differences in victimization and negative emotions from a developmental general strain theory perspective. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2023, 48, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands-resources theory in times of crises: New propositions. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 13, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, J.P.; Jaramillo, J.F.; Locander, W.B. Critical role of leadership on ethical climate and salesperson behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, M. A paradox of ethics: Why people in good organizations do bad things. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 184, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-González, M.; Alcalá-Ibañez, M.L.; Castán-Esteban, J.L.; Martín-Bielsa, L.; Gallardo, L.O. COVID-19 in school teachers: Job satisfaction and burnout through the job demands control model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, C.; Roberts, T.L.; Lowry, P.B. The impact of organizational commitment on insiders’ motivation to protect organizational information assets. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 32, 179–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, M.J. The impact of job insecurity on knowledge-hiding behavior: The mediating role of organizational identification and the buffering role of coaching leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trittin-Ulbrich, H. From the substantive to the ceremonial: Exploring interrelations between recognition and aspirational CSR talk. Bus. Soc. 2023, 62, 917–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.; Li, H.; Tong, Y.H. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and stakeholder engagement: Evidence from the quantity and quality of CSR disclosures. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Elbanna, S. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) implementation: A review and a research agenda towards an integrative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 183, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Yao, H.; Zhang, M. CSR gap and firm performance: An organizational justice perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Jafar, R.M.S.; Waheed, A.; Sun, H.; Kazmi, S.S.A.S. Determinants of CSR and green purchase intention: Mediating role of customer green psychology during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 135888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battisti, E.; Nirino, N.; Leonidou, E.; Salvi, A. Corporate social responsibility in family firms: Can corporate communication affect CSR performance? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 162, 113865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cherian, J.; Han, H. CSR and organizational performance: The role of pro-environmental behavior and personal values. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, F.M.; Novick, M.R.; Birnbaum, A. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, R.; Mackay, C.J.; Clarke, S.D.; Kelly, C.; Kelly, P.J.; McCaig, R.H. ‘Management standards’ work-related stress in the UK: Practical development. Work. Stress 2004, 18, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.S.; Shin, Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJoy, D.M.; Wilson, M.G.; Vandenberg, R.J.; McGrath-Higgins, A.L.; Griffin-Blake, C.S. Assessing the impact of healthy work organization intervention. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motowidlo, S.J.; Packard, J.S.; Manning, M.R. Occupational stress: Its causes and consequences for job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Understanding information systems security policy compliance: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayachee, K. Taxonomy of compliant information security behavior. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brace, N.; Kemp, R.; Snelgar, R. A Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jex, S.M. Stress and Job Performance: Theory, Research, and Implications for Managerial Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Macey, W.H. Organizational climate and culture. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 199 | 52.8% |

| Women | 178 | 47.2% | |

| Age (years) | 20–29 | 81 | 21.5% |

| 30–39 | 86 | 22.8% | |

| 40–49 | 111 | 29.4% | |

| 50–59 | 99 | 26.3% | |

| Educational Level | High school or below | 45 | 11.9% |

| Community college | 77 | 20.4% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 206 | 54.6% | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 49 | 13.0% | |

| Position | Staff | 157 | 41.6% |

| Assistant manager | 62 | 16.4% | |

| Manager or deputy general manager | 92 | 24.4% | |

| Department/general manager or director and above | 66 | 17.5% | |

| Industry Type | Manufacturing | 81 | 21.5% |

| Services | 63 | 17.8% | |

| Construction | 41 | 10.9% | |

| Health and welfare | 59 | 15.6% | |

| Information services and telecommunications | 36 | 9.5% | |

| Education | 57 | 15.1% | |

| Financial/insurance | 8 | 2.1% | |

| Consulting and advertising | 3 | 0.8% | |

| Others | 29 | 7.7% |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.47 | 0.50 | - | ||||

| 2. Tenure | 65.24 | 73.12 | −0.10 | - | |||

| 3. WO | 2.65 | 0.88 | −0.15 ** | −0.04 | - | ||

| 4. CE | 3.28 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.24 ** | −0.004 | - | |

| 5. JS | 2.87 | 0.84 | 0.00 | −0.11 * | 0.40 ** | −0.12 * | - |

| 6. CB | 3.66 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.13 * | −0.12 * | 0.26 ** | −0.26 ** |

| Hypothesis | Path (Relationship) | Unstandardized Estimate | S.E. | Standardized Estimate | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Work overload → Cybersecurity Behavior | −0.016 | 0.045 | −0.023 | No |

| 2 | Work overload → Job Stress | 0.357 | 0.048 | 0.405 *** | Yes |

| 3 | Job Stress → Cybersecurity Behavior | −0.212 | 0.048 | −0.262 *** | Yes |

| 5 | Work overload × Corporate Ethics | −0.249 | 0.053 | 0.232 *** | Yes |

| Model (Hypothesis 4) | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work overload → Job Stress → Cybersecurity Behavior | 0.000 | 0.106 | −0.106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, Y.; Kim, M.-J.; Roh, T. Mitigating the Impact of Work Overload on Cybersecurity Behavior: The Moderating Influence of Corporate Ethics—A Mediated Moderation Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914327

Hong Y, Kim M-J, Roh T. Mitigating the Impact of Work Overload on Cybersecurity Behavior: The Moderating Influence of Corporate Ethics—A Mediated Moderation Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914327

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Yunsook, Min-Jik Kim, and Taewoo Roh. 2023. "Mitigating the Impact of Work Overload on Cybersecurity Behavior: The Moderating Influence of Corporate Ethics—A Mediated Moderation Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914327

APA StyleHong, Y., Kim, M.-J., & Roh, T. (2023). Mitigating the Impact of Work Overload on Cybersecurity Behavior: The Moderating Influence of Corporate Ethics—A Mediated Moderation Analysis. Sustainability, 15(19), 14327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914327