The Influence of Commitment to Change and Change-Related Behaviour among Academics of Malaysian-Islamic Higher Learning Institutions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- i.

- To ensure the graduates are able to become job creators rather than job seekers by encouraging an entrepreneurial mindset throughout the Malaysian higher education system.

- ii.

- To come up with a system that focuses more on technical and vocational training rather than just paying attention to academic routes.

- iii.

- To give emphasis on output over input and to actively focus on students’ personalised learning through technology and innovation

- iv.

- To better coordinate both public and private universities and to move away from being highly centralised

- v.

- To ensure that higher learning institutions become less dependent on government resources

2. Literature Review

2.1. Change Management in Malaysian Higher Learning Institutions

2.2. Research Gap

- Islamic higher learning institutions carry the Islamic value that knowledge should be shared. In doing so, it is crucial for the Islamic HLIs to keep up with the modernization and development that is taking place in the education industry [27]. However, evidence has pointed to the fact that Islamic HLIs are left behind compared to their conventional counterparts due to their inability to adapt to changes [26]. Commitment to change has been cited to be a crucial factor for successful change implementation, as it determines how employees are able to adapt and embrace change. Studies on addressing this need are [26,27]. Thus, this research addresses this gap by studying the influence of commitment to change on change-related behaviour in Malaysian-Islamic HLIs.

- Studies on the commitment to change in Malaysian HLIs have mainly focused on HLIs in general without differentiating between Islamic and conventional HLIs [23,24,25]. The values in Malaysian-Islamic HLIs are different from their conventional counterparts [27]. Studying how commitment to change influences the behaviour of employees would be able to add on to the body of knowledge in this area of change management in HLIs [26,27].

2.3. Underlying Theory

2.3.1. The Social Exchange Theory

2.3.2. Three-Component Model of Commitment to Change

2.4. Commitment to Change

2.5. Change-Related Behaviour

2.6. Commitment to Change and Change-Related Behaviour

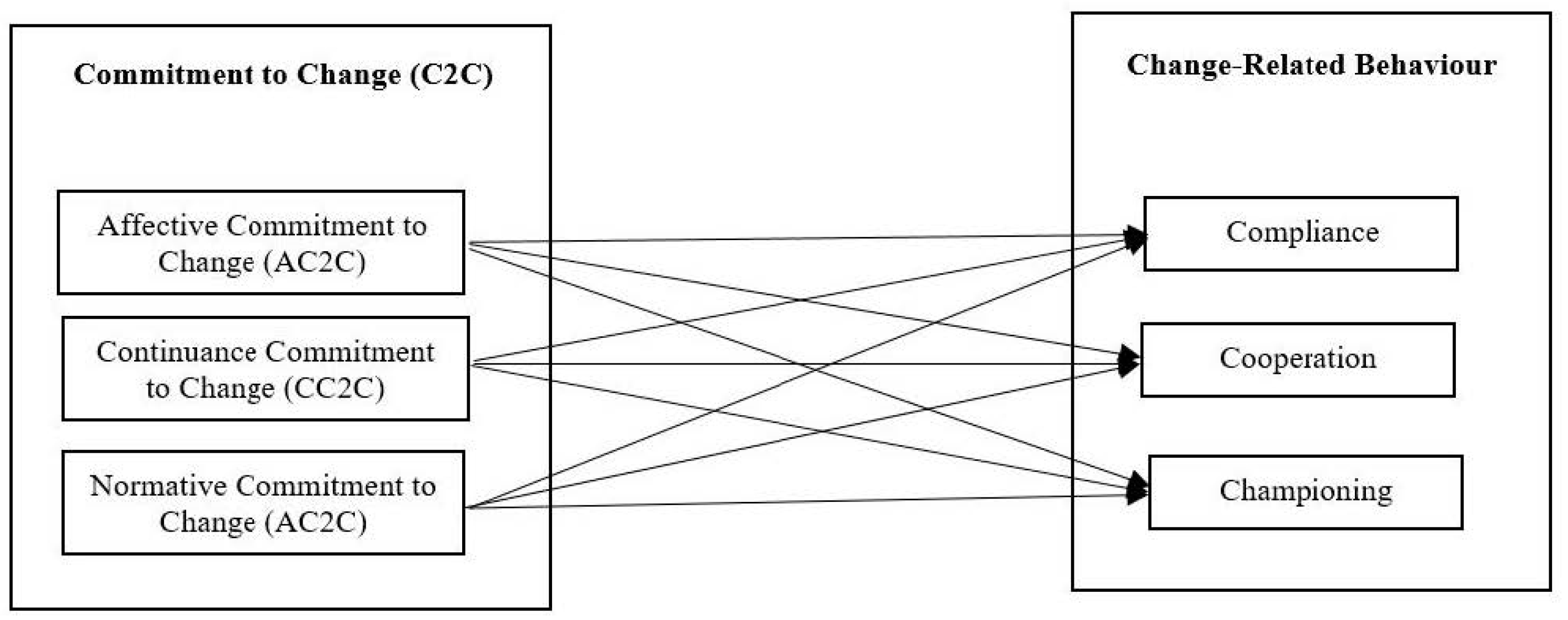

2.7. Conceptual Framework

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection Tools

3.1.1. Commitment to Change Scale

“The changes introduced by the university serves am important purpose”

“I have a lot to lose if I resist the changes implemented by the university”

“It is not right for me to oppose the changes implemented by the university”

3.1.2. Change Related Behaviour Scale

“I encourage the participation of others in implementing changes initiated by the university”

“I do not complain about the changes implemented by the university”

“I accept the role changes within the university because I have to”

3.2. Data Analysis Tool

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

4.2. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bayraktar, S.; Jiménez, A. Self-efficacy as a resource: A moderated mediation model of transformational leadership, extent of change and reactions to change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somadi, N.; Salendu, A. Mediating Role of Employee Readiness to Change in the Relationship of Change Leadership with Employees’ Affective Commitment to Change. Bp. Int. Res. Crit. Inst. J. 2022, 5, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, T. 5 Pillars of Sustainable Organizational Change. Change Management Insight. 6 December 2022. Available online: https://changemanagementinsight.com/five-pillars-of-sustainable-change/ (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Rieg, N.A.; Gatersleben, B.; Christie, I. Driving Change towards Sustainability in Public Bodies and Civil Society Organisations: Expert Interviews with UK Practitioners. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouten, J.; Rousseau, D.M.; de Cremer, D. Successful Organizational Change: Integrating the Management Practice and Scholarly Literatures. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2018, 12, 752–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H. Transformation of Higher Education: A Stakeholder Perspectives in Private Islamic Higher Education Institution (IPTIS) in Malaysia. Holistica 2019, 10, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteijlen, M.; Wals, A.E.J. Developing Design Principles for Sustainability-Oriented Blended Learning in Higher Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainun, N.F.H.; Johari, J.; Adnan, Z. Stressor factors, internal communication and commitment to change among administrative staff in Malaysian public higher-education institutions. Horizon 2018, 26, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education Malaysia. Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015–2025. Higher Education. 2013. Available online: https://www.moe.gov.my/menumedia/media-cetak/penerbitan/dasar/1207-malaysia-education-blueprint-2013-2025/file (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- Leal Filho, W.; Pimenta Dinis, M.A.; Sivapalan, S.; Begum, H.; Ng, T.F.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Alam, G.M.; Sharifi, A.; Salvia, A.L.; Kalsoom, Q.; et al. Sustainability practices at higher education institutions in Asia. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 23, 1250–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, R. Tertiary Education Redesigned. New Straits Times. 21 January 2017. Available online: https://www.nst.com.my/news/2017/03/206101/tertiary-education-redesigned (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Thomas, J. Malaysia: Between Education and Skills. The ASEAN Post, 28 November 2019. Available online: https://theaseanpost.com/article/malaysia-between-education-and-skills(accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Gigliotti, R.; Vardaman, J.; Marshall, D.R.; Gonzalez, K. The Role of Perceived Organizational Support in Individual Change Readiness. J. Chang. Manag. 2018, 19, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechanova, M.R.M.; Caringal-Go, J.F.; Magsaysay, J.F. Implicit change leadership, change management, and affective commitment to change: Comparing academic institutions vs business enterprises. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Raath, S.; Lazzarini, B.; Vargas, V.R.; de Souza, L.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Haddad, R.; Klavins, M.; Orlovic, V.L. The role of transformation in learning and education for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaoui, A.; Benmoussa, R. Employees’ attitudes toward change with Lean Higher Education in Moroccan public universities. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 253–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F.; Licciardello, S.A. Towards sustainable organizations: Supervisor support, commitment to change and the mediating role of organizational identification. Sustainability 2019, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangundjaya, W.L.; Amir, M.T. Testing Resilience and Work Ethics as Mediators Between Charismatic Leadership and Affective Commitment to Change. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainun, N.F.H.; Johari, J.; Adnan, Z. Technostress and Commitment to Change: The Moderating Role of Internal Communication. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 43, 1327–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, B.; Guo, Y.; Chen, D. Change Leadership and Employees’ Commitment to Change. J. Pers. Psychol. 2018, 17, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, J.; Ram, B.R.; Soliman, M.; Ali, A.J.; Khaleel, M.; Islam, M.S. Promising digital university: A pivotal need for higher education transformation. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 12, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.; Ramayah, T.; De Run, E.C. Does transformational leadership style foster commitment to change ? The case of higher education in Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 5384–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.; Ramayah, T.; De Run, E.C.; Ling, V.M. “New Leadership”, Leader-Member Exchange and Commitment to Change: The Case of Higher Education in Malaysia. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2009, 53, 574–580. [Google Scholar]

- Daif, K.; Yusof, N. Change in Higher Learning Institutions: Lecturers’ Commitment to Organizational Change (C2C). Inernational. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 182–194. [Google Scholar]

- Shariffuddin, S.; Razali, J.; Ghani, M.A.; Wan Shaaidi, W.R. Transformation of higher education institutions in Malaysia: A review. J. Glob. Bus. Soc. Entrep. 2017, 1, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Nurdin, A. Modernization of Islamic Higher Education in Indonesia at A Glance: Barriers and Opportunities. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2021, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Nya-Ling, C.T.; Thurasamy, R.; Ojo, A.O.; Shogar, I. Muslim academics’ knowledge sharing in Malaysian higher learning institutions. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwaningrum, E.K.; Suhariadi, F.; Fajrianthi. Participation and Commitment to Change on Middle Managers in Indonesia: The Role of Perceived Organizational Support as Mediator. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 23, 1218–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herscovitch, L.; Meyer, J.P. Commitment to Organizational Change: Extension of a Three-Component Model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Z. Motivational bases of commitment to organizational change in the Chinese public sector. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Robin, M.; Fan, L.; Huang, X. Commitment to change: Structure clarification and its effects on change-related behaviors in the Chinese context. Pers. Rev. 2019, 49, 1069–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangundjaya, W.L. Leadership, empowerment, and trust on affective commitment to change in state-owned organisations. Int. J. Public Sect. Perform. Manag. 2019, 5, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, D.M.; Fedor, D.B.; Caldwell, S.; Liu, Y. The Effects of Transformational and Change Leadership on Employees’ Commitment to a Change: A Multilevel Study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, P.; Garg, P. The relationship between learning culture, inquiry and dialogue, knowledge sharing structure and affective commitment to change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2017, 30, 610–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.S. Impact of change readiness on commitment to technological change, focal, and discretionary behaviors Evidence from the manufacturing. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2016, 29, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, M.S.; Men, L.R.; Yue, C.A. How communication climate and organizational identification impact change. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2020, 25, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Chinese teachers’ perspectives on teachers’ commitment to change. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2016, 18, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straatmann, T.; Nolte, J.K.; Seggewiss, B.J. Psychological processes linking organizational commitment and change-supportive intentions. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, P.L.; Chênevert, D.; Jobin, M.H. The antecedents of physicians’ behavioral support for lean in healthcare: The mediating role of commitment to organizational change. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 232, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.L.; Harisson, W. The Roles of Affective Commitment to Change, Organizational Justice, and Organizational Cynicism. J. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 19, 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, K.; Lee, J. Transformational leadership and follower’s innovative behavior: Roles of commitment to change and organizational support for creativity. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative Versus Reflective Indicators in Organizational Measure Development: A Comparison and Empirical Illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahzar, M. Authentic Leadership in Madrassas: Asserting Islamic Values in Teacher Performance. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2019, 10, 259–284. [Google Scholar]

| Championing | Compliance | Cooperation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective Commitment to Change | 1.154421 | 1.154421 | 1.154421 |

| Continuance Commitment to Change | 1.157463 | 1.157463 | 1.157463 |

| Normative Commitment to Change | 1.279251 | 1.279251 | 1.279251 |

| Scale | No of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC2C | 4 | 0.885 | 0.921 |

| CC2C | 4 | 0.741 | 0.638 |

| Champ | 6 | 0.857 | 0.895 |

| Comp | 3 | 0.720 | 0.833 |

| Coop | 3 | 0.724 | 0.840 |

| NC2C | 4 | 0.785 | 0.865 |

| Saturated Model | Estimated Model | |

|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.078 | 0.080 |

| Beta | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC2C -> Champ | 0.506 | 0.092 | 5.523 | 0.000 |

| AC2C -> Comp | 0.370 | 0.254 | 1.458 | 0.072 |

| AC2C -> Coop | 0.437 | 0.085 | 5.138 | 0.000 |

| CC2C -> Champ | 0.171 | 0.177 | 0.963 | 0.168 |

| CC2C -> Comp | 0.376 | 0.158 | 2.378 | 0.009 |

| CC2C -> Coop | 0.256 | 0.201 | 1.274 | 0.101 |

| NC2C -> Champ | 0.102 | 0.115 | 0.882 | 0.189 |

| NC2C -> Comp | 0.085 | 0.177 | 0.482 | 0.315 |

| NC2C -> Coop | 0.189 | 0.114 | 1.669 | 0.048 |

| Hypothesis | p Values | Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1a: Affective commitment to change has a significant influence on compliance | 0.072 | Not Supported |

| H1b: Affective commitment to change has a significant influence on cooperation | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1c: Affective commitment to change has a significant influence on championing | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2a: Continuance commitment to change has a significant influence on compliance | 0.009 | Supported |

| H2b: Continuance commitment to change has a significant influence on cooperation | 0.101 | Not Supported |

| H2c: Continuance commitment to change has a significant influence on championing | 0.168 | Not Supported |

| H3a: Normative commitment to change has a significant influence on compliance | 0.315 | Not Supported |

| H3b: Normative commitment to change has a significant influence on cooperation | 0.048 | Supported |

| H3c: Normative commitment to change has a significant influence on championing | 0.189 | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohd Noor, A.; Dorasamy, M.; Raman, M. The Influence of Commitment to Change and Change-Related Behaviour among Academics of Malaysian-Islamic Higher Learning Institutions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914250

Mohd Noor A, Dorasamy M, Raman M. The Influence of Commitment to Change and Change-Related Behaviour among Academics of Malaysian-Islamic Higher Learning Institutions. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914250

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohd Noor, Azrena, Magiswary Dorasamy, and Murali Raman. 2023. "The Influence of Commitment to Change and Change-Related Behaviour among Academics of Malaysian-Islamic Higher Learning Institutions" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914250

APA StyleMohd Noor, A., Dorasamy, M., & Raman, M. (2023). The Influence of Commitment to Change and Change-Related Behaviour among Academics of Malaysian-Islamic Higher Learning Institutions. Sustainability, 15(19), 14250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914250