The Influence of Capability, Business Innovation, and Competitive Advantage on a Smart Sustainable Tourism Village and Its Impact on the Management Performance of Tourism Villages on Java Island

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Village Capability

2.2. Business Innovation

2.3. Competitive Advantage

2.4. Smart Sustainable Tourism Village

2.5. Performance of Tourism Village Management

2.6. Previous Research

- The effect of capability on smart sustainable tourism villages on the island of Java;

- The effect of business innovation on smart sustainable tourism villages on the island of Java;

- The effect of competitive advantage on smart sustainable tourism villages on the island of Java;

- The effect of tourism village capability on the management performance of tourist villages on the island of Java;

- The effect of business innovation on the management performance of tourist villages on the island of Java;

- The effect of competitive advantage on the management performance of tourist villages on the island of Java;

- The effect of smart sustainable tourism villages on the management performance of tourist villages on the island of Java.

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Identity of Tourism Village Respondents

4.2. Research Instrument Test (Validity and Reliability Test)

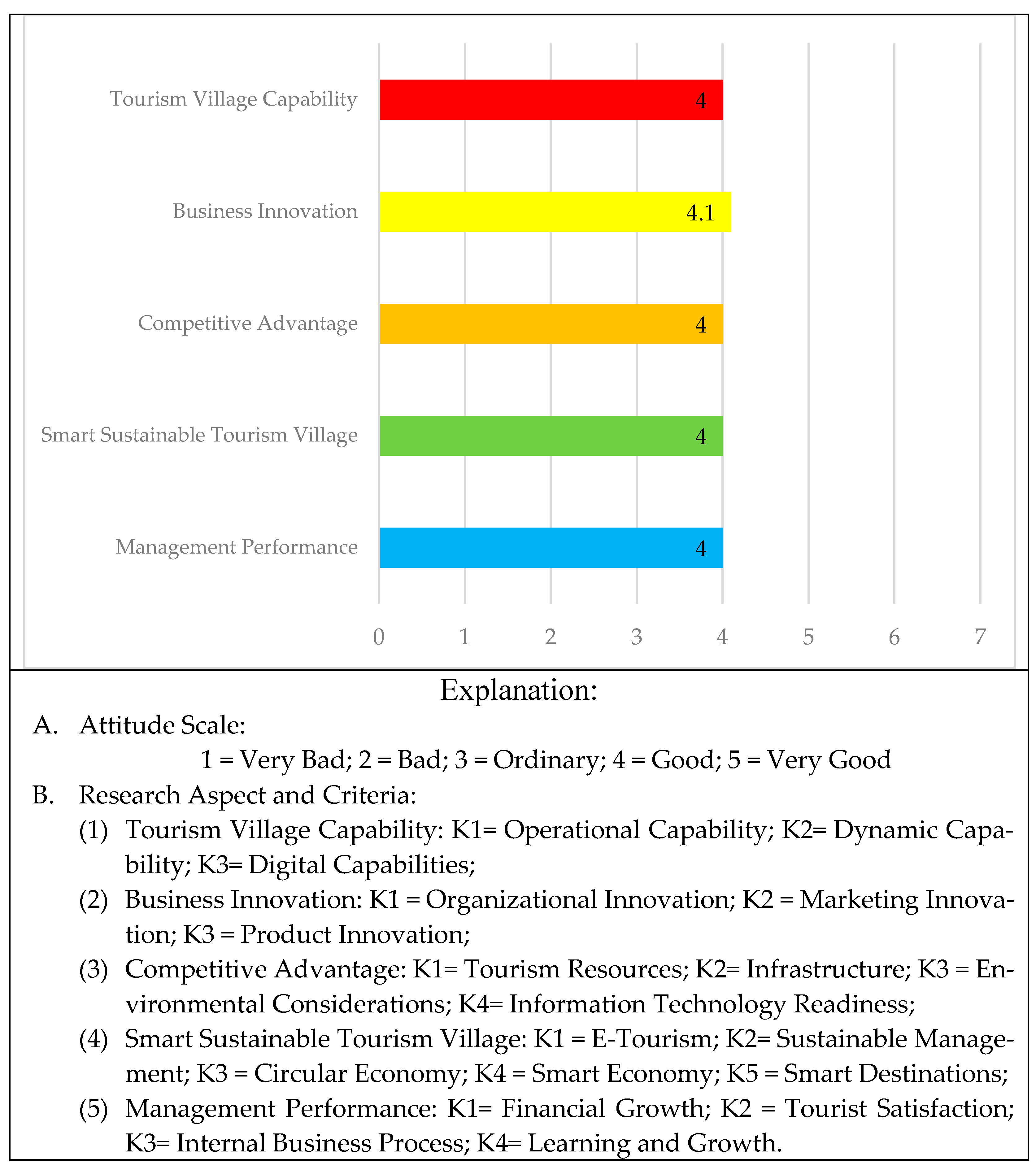

4.3. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

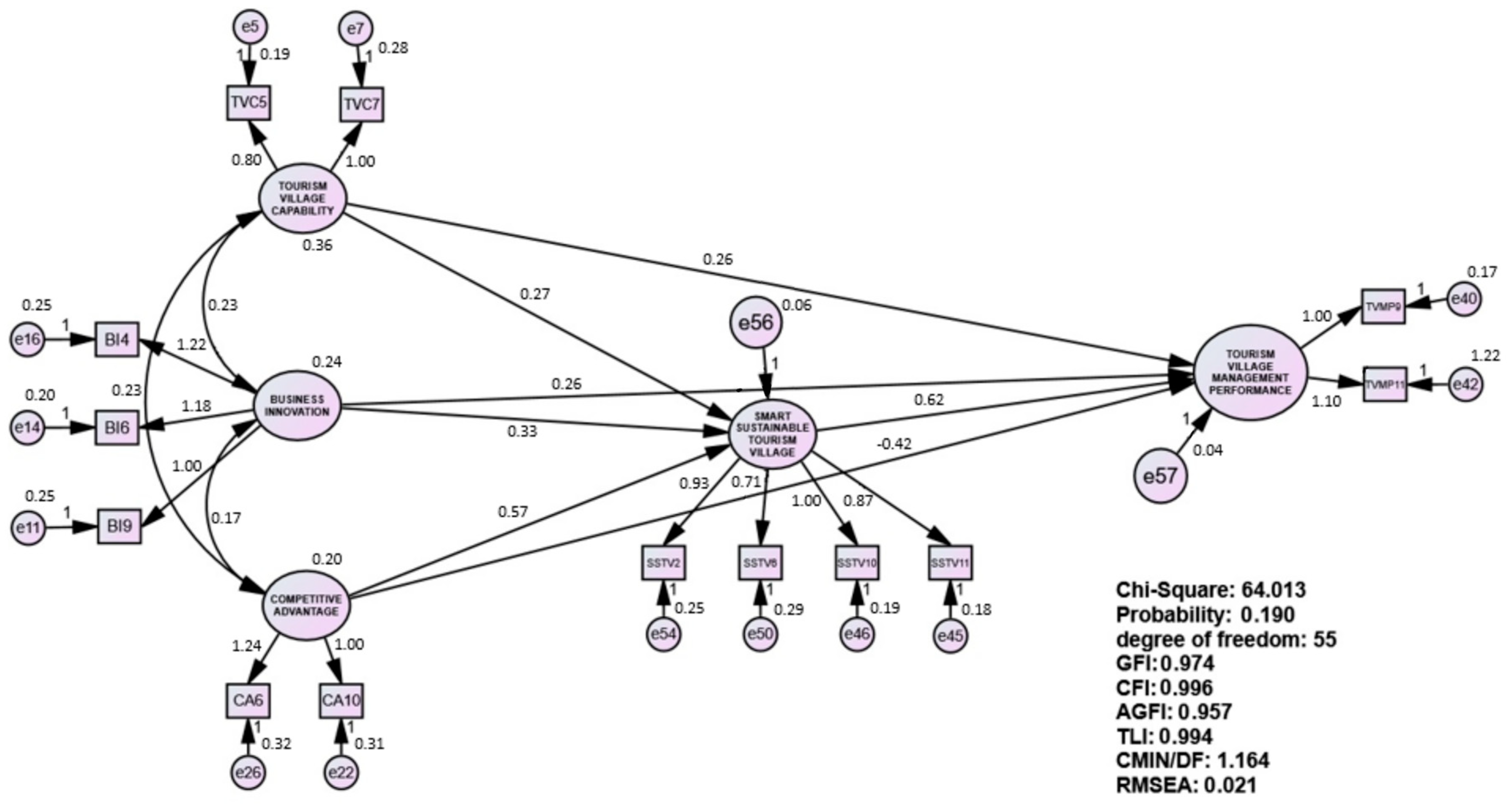

4.4. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Test

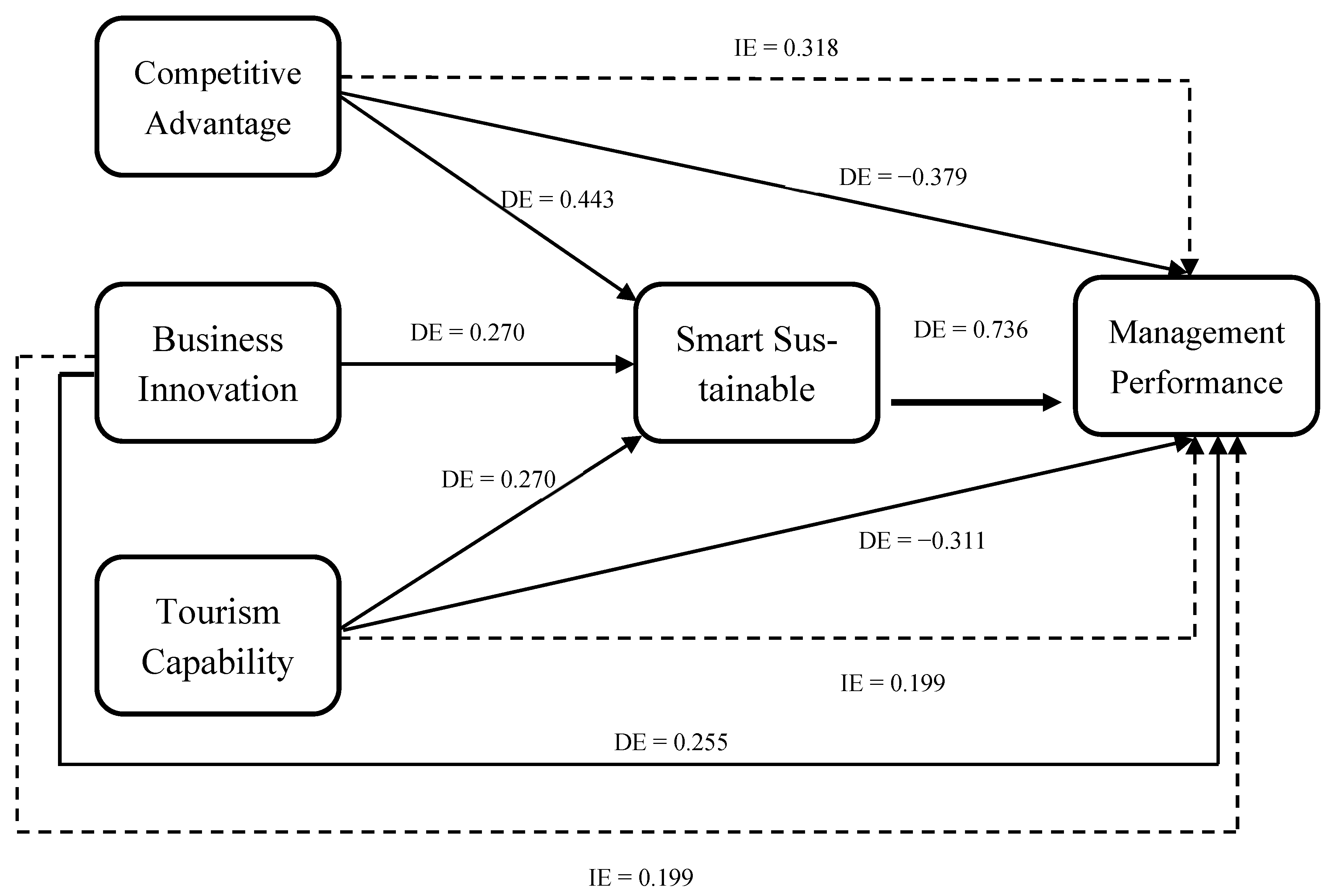

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Implications

6.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, G.; Yang, J. The recovery strategy of Rural Tourism post-epidemic period. In Advance in Economics, Business and Management Research; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 614. [Google Scholar]

- WTTC. World Travel and Tourism Council, Travel and Tourism Economic Impact from COVID-19. 2020. Available online: www.wttc.org (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- BPS. Badan Pusat Statistik, Jumlah Desa Wisata di Indonesia; BPS: London, UK, 2020; Available online: www.bps.go.id (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Coordinating Ministry for Maritime and Investment Affairs. Indonesian: Kementerian Koordinator Bidang Kemaritiman dan Investasi, Tourism Village Guide; Coordinating Ministry for Maritime and Investment Affairs: Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022. Available online: https://maritim.go.id/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Desa Wisata Institute. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourism Villages in Indonesia; Desa Wisata Institute: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2021; Available online: https://desawisatainstitute.com/riset/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- WEF. World Economic Forum, Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Indext: Rebuilding for Sustainable and Resilient Future; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Wijaya. ICT Readiness Analysis in smart rural tourism implementation in Sleman Regency. Sosiohhumaniora 2018, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Shahabuddin, M.; Alam, T.; Krishna, B.B.; Bhaskar, T. A review on the production of renewable aviation fuels from the gasification of biomass and residual wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 312, 123596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pranita, D.; Sarjana, S.; Mustofa, M.B.; Kusumastuti, H. Blockchain Technology to Enhance Integrated Blue Economy: A Case Study in Strengthening Sustainable Tourism on Smart Islands. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Baggio, R.; Micera, R. Smart tourism destinations: A critical reflection. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2020, 11, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaenal, Z.A.; Kamase, J.; Serang, S. Analisis digital marketing dan word of mouth sebagai strategi promosi pariwisata. Tata Kelola 2020, 7, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital 2022: Global Overview Report. 2022. Available online: http://datareportal.com (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- WTTC; Microsoft. Codes to Resilience: Cyber Resilience in Travel and Tourism; World Travel & Tourism Council: London, UK; Microsoft: Sydney, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2022/WTTC_x_Microsoft-Codes_To_Resilience.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Khrisnamurti, U.H.; Darmawan, R. The impacts of tourism activities on the environment in tidung island, kepulauan seribu. Kajian 2016, 21, 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Coros, M.M.; Gica, O.A.; Yallop, A.C.; Moisescu, O.I. Innovative and sustainable tourism strategies: A viable alternative for Romania’s economic development. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 504–515. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T.; Kim, S. Exploring the relationship between tourism and poverty using the capability approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1655–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmeier, A. Dynamic capability building and social upgrading tourism—Potentials and limits of sustainability standards. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1498–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P.F. Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Pan Business Management: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis, C. An ecological worldview perspective on urban sustainability. In Proceedings of the ELECS 2009, Recife, Brazil, 28–30 October 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis, M. The role of knowledge management in innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value Creation in E-Business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Frankelius, P. Questioning two myths in innovation literature. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2009, 20, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Boris, D.; Plüschke, B.D.; Pesch, R.; Kraus, S. Entrepreneurial orientation in vertical alliances: Joint product innovation and learning from allies. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2016, 10, 381–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwan, R.M. Novel Business Model: An Empirical Study of Antecedents and Consequences; Newcastle University: Newcastle, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Daniloska, N.; Mihajlovska, K.H.N. Rural Tourism and Sustainable Rural Development. Econ. Dev. 2015, 3, 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmat, I.; Cahyadi, A. Desa wisata berkelanjutan di nglanggeran: Sebuah taktik inovasi. J. Pariwisata Pesona 2019, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.M. A review of innovation research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooroochurn, N.; Sugiyarto, G. Competitiveness Indicators in the Travel and Tourism Industry. Torism Econ. 2005, 11, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Hauteserre, A.M. Lessons managed destination competitiveness: The case of foxwoods casino resort. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bris, A.; Caballero, J. The USA Continues to Top the Ranking; Asia Experiences Mixed Results; and Large Emerging Economies Mostly Linger. IMD Releases Its 2015 World Competitiveness Ranking. 2015. Available online: www.imd.org/wcc (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Lengnick-Hall, M.L.; Lengnick-Hall, C.A. Human Resource Management in the Knowledge Economy: New Challenges, New Roles, New Capabilities; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Harvard Business Review; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Suta, W.P.; Abdi, N.; Astawa, I.P.M. Sustainable Tourism Development in Importance and Performance Perspective: A Case Study Research in Bali. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2020, 55, 342–346. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; DesJardine, M.R. Business sustainability: It is about time. Strateg. Organ. 2014, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.A.; Isa, S.M. Exploring The Sustainable Tourism Practices among Tour Operators In Malaysia. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2020, 15, 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambientintelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council. Criteria for Hotel and Tour Operators; Global Sustainable Tourism Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafa, N.; Hani, Y.; Mhamedi, A.E. Sustainability performance measurement for green supply chain management. IFAC Proc. 2013, 46, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Wu, Z.; Wasserman, M.E. Thinking differently about purchasing portfolios: An assessment of sustainable sourcing. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2010, 46, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason-Jones, R.; Naylor, B.; Towill, D.R. Lean, agile or leagile? Matching your supply chain to the marketplace. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010, 38, 4061–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.; Legun, K.; Campbell, H.; Carolan, M. Social sustainability indicators as performance. Geoforum 2019, 103, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husgafvel, R.; Pajunen, N.; Virtanen, K.; Paavola, I.L.; Paavola, M.P.; Inkinen Inkinen, V.; Heiskanen, K.; Dahl, O.; Ekroos, A. Social sustainability performance indicators–experiences from process industry. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2015, 8, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E. From Neglect to Progress: Assessing Social Sustainability and Decent Work in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Moreira, J. Social Sustainability of Water and Waste Management Companies in Portugal. Sustainability 2021, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloum, R.S. The role of business models in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s Technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.; Lehmann, C.; Fellnhofer, K. The role of entrepreneurial orientation and modularity for business model innovation in services companies. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2016, 8, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Laursen, K.; Pedersen, T. Linking customer interaction and innovation: The mediating role of new organizational practices. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 980–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavou, H.; Lioukas, S. Radical product innovations in SMEs: The dominance of entrepreneurial orientation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2003, 12, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzen, A.; Iqbal, M.; Abdillah, Y. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation, customer orientation, and knowledge sharing on innovation capability and business performance. Wacana 2019, 22. Available online: https://wacana.ub.ac.id/index.php/wacana/article/view/664/423 (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Hermanto, S.H. The role of coaching, capability, and innovation on the performance of SMEs in the Kenjeran Tourism Area in Surabaya. Acc. Financ. Manag. J. 2018, 3, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe. Research Method for Busines; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyono. Qualitative, Quantitative, and R&D; CV Alfabeta: Bandung, Indonesia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Avenzora, R. Ecotourism. Theory and Practical; BRR NAD-Nias: Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger, F.N.; Lee, H.B. Foundations of Behavioral Research, 4th ed.; Harcourt College Publishers: Forth Worth, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U. Researh Method for Business, 4th ed.; Salemba Empat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.; Schindler, P. Business Research Methods, 9th ed.; McGraw Hill International Edition: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, K.D. Marketing Research, 10th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Manaf, A.; Purbasasi, N.; Damayanti, M.; Aprilia, N.; Astuti, W. Community-based rural tourism in inter-organizational collaboration: How does it work sustainably? Lessons learned from Nglanggeran Tourism Village, Gunungkidul Regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmatullah, A.; Avenzora, R.; Sunarminto, T. The polarization of orientation amongst locals on cultural-land utilization or ecotourism development in Ranah Minang, Sumatera Barat. J. Reg. City Plan. 2023, 34, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachrunissa, I. Analisis Daya Saing Dan Keberlanjutan Desa Wisata Cibuntu Kabupaten Kuningan Jawa Barat. Master’s Thesis, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Kabupaten Bogor, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zatori, A.; Beardsley, M. On-site and memorable tourist experiences: Trending toward value and quality-of-life outcomes. Adv. Hosp. Leis. 2017, 13, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevão, C.; Ferreira, J. Regional Competitiveness of Tourism Cluster: A Conceptual Model Proposal; Paper No. 14853; Universidade do Algarve: Faro, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blain, C.; Levy, S.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Destination branding: Insights and practices from destination management organizations. J. Travel Res. 2005, 40, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Pride, R. Tourism places, brands, and reputation management. Destin. Brands 2011, 3, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudaryati, D.; Heriningsih, S. Pengaruh motivasi, budaya organisasi dan sistem informasi desa terhadap kinerja pemerintah desa. Kompartemen J. Ilm. Akunt. 2019, 17, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, A.L.A.; Handayani, N. Pengaruh partisipasi anggaran, budaya organisasi, dan teknologi terhadap kinerja pemerintah aparat desa. J. Ilmu Dan Ris. Akunt. 2020, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lubis, A.; Sari, E.N.; Astuty, W. Pengaruh kualitas sumber daya manusia dan pemanfaatan teknologi terhadap sistem pengelolaan dana desa serta dampak terhadap kinerja pemerintah desa di kabupaten deli serdang. J. Mutiara Akunt. 2020, 5, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Nurjaya, N.; Affandi, A.; Ilham, D.; Jasmani, J.; Sunarsi, D. Pengaruh kompetensi sumber daya manusia dan kemampuan pemanfaatan teknologi terhadap kinerja aparatur desa pada kantor kepala desa di Kabupaten Gunungkidul, Yogyakarta. J. Ilm. Manaj. Sumber Daya Mns. 2021, 4, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.L.; Chen, J.L. A stage-based diffusion of IT innovation and the BSC performance impact: A moderator of technology-organization-environment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2014, 88, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitul; Ilona, D.; Novianti, N.; Widiningsih, F.A. Difunsi inovasi sistem informasi dan kinerja porses internal pemerintahan desa destinasi wisata: Kebermanfaatan teknologi sebagai variabel moderasi. In Proceedings of the 1st LP31 National Conference of Vocational Business and Technology (LICOVBITECH), Jakarta, Indonesia, 17 September 2022; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Avenzora, R.; Batubara, R.P.; Fajrin, R.F.; Sagita, E.; Armiliza, P.R.; Amelia, M.; Romansyah, B.; Arifullah, N. Nagari Ecotourism in Ranah Minang, West Sumatra Barat. In Ecotourism and Sustainable Tourism Development in Indonesia—The Potential, Lessons and Best Practice; Teguh, M.A., Avenzora, R., Eds.; Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy and PT Gramedia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013; pp. 320–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ira, W.S.; Muhamad, M. Paritisipasi Masyarakat pada Penerapan Pengembangan Pariwisata Berkelanjutan (Studi Kasus Desa Wisata Pujon Kidul, Kabupaten Malang). J. Pariwisata Terap. 2020, 3, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Desa Wisata Nglanggeran Jadi Wakil Indonesia pada Ajang Best Tourism Village UNWTO. 2021. Available online: https://www.kemenparekraf.go.id/ragam-pariwisata/Desa-Wisata-Nglanggeran-Jadi-Wakil-Indonesia-pada-Ajang-Best-Tourism-Village-UNWTO (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Rudiadi, R.; Ilosa, A.; Alsukri, S. Optimalisasi kinerja pemerintahan desa dalam penyusunan rencana kerja pembangunan desa. J. El-Riyasah 2021, 12, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Saputra, A. Tata kelola pemerintahan desa terhadap peningkatan pelayanan publik di Desa Pematang Johar. War. Dharmawangsa 2020, 14, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappey, C.V.; Trappey, A.J.; Chang, A.C.; Huang, A.Y. Clustering analysis prioritization of automobile logistics services. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelbst, P.J.; Frazier, G.V.; Sower, V.E. A cluster concentration typology for making location decisions. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 883–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, N.; Gunasekaran, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Nie, P. 4th party logistics service providers and industrial cluster competitiveness. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1303–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R. Assessing Tourism Development from Sen’s Capability Approach. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazilu, M. Sustainable Tourism of Destination, Imperative Triangle Among: Competitiveness, Effective Management and Proper Financing; University of Craiova: Craiova, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Esparon, M.; Stoeckl, N.; Farr, M.; Larson, S. The significance of environmental values for destination competitiveness and sustainable tourism strategy making insights from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idarraga, D.A.M.; Marin, J.C.C. Relationship between innovation and performance: Impact of competitive intensity and organizational slack. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 59, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, I.N.; Massie, J.D.D.; Tumewu, F.J. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation and innovation capability towards firm performances in small and medium enterprises. J. EMBA 2019, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.J.M.; Fernandes, C.I.; Ferreira, F.A.F. To be or not to be digital, that is the question: Firm innovation and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 101, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booyens, I. Global–local trajectories for regional competitiveness: Tourism innovation in the Western Cape. Local Econ. 2016, 31, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boycheva, C. Innovation and competitiveness in the context of Bulgarian tourism industry. Econ. Altern. 2017, 1, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Dragomir, L.; Mazilu, M.; Marinescu, R.; Bălă, D. A Competitiveness and Innovativeness in The Attractiveness of a Tourist Destination: Case Study—Tourist Destination Oltenia. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2019, 6, 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Fernandes, C.I.; Ratten, V. Entrepreneurship, innovation and competitiveness: What is the connection? Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2017, 18, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazargani, R.; Kiliç, H. Tourism competitiveness and tourism sector performance: Empirical insights from new data. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, M.; Zulkifly, M. Tourism destination competitiveness and tourism performance: A secondary data approach. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2019, 29, 592–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Conesa, J.A.; de Nieves Nieto, C.; Briones-Peñalver, A.J. CSR Strategy in Technology Companies: Its Influence on Performance, Competitiveness and Sustainability. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiputra, I.P.P.d.K. Mandala Pengaruh Kompetensi Dan Kapabilitas Terhadap Keunggulan Kompetitif Dan Kinerja Perusahaan. E-J. Manaj. Unud. 2017, 6, 6090–6119. [Google Scholar]

- Sartika, D. Inovasi Organisasi Dan Kinerja Organisasi: Studi Kasus Pada Pusat Kajian dan Pendidikan dan Pelatihan Aparatur Iii Lembaga Administrasi Negara. J. Borneo Adm. 2015, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaeni, T. Pengaruh Strategi Inovasi Terhadap Keunggulan Bersaing di Industri Kreatif (Studi Kasus UMKM Bidang Kerajinan Tangan di Kota Bandung). J. Ris. Bisnis Dan Investasi 2018, 4, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi-Vallbona, M.; Mascarilla-Miró, O. Street art as a sustainable tool in mature tourist destinations: A case study of Barcelona. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2021, 27, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihasa, I.G.M.; Widawati, I.A.P.; Mahadewi, N.M.E. Pembangunan Pariwisata di Desa Wisata Penglipuran Melalui Peran Partisipasi Masyarakat, Kewirausahaan Sosial Berkelanjutan dan Inovasi, Ekuitas. J. Pendidik. Ekon. 2022, 10, 290–305. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Angelkova, T.; Koteski, C.; Jakovleva, Z.; Mitrevska, E. Sustainability and Competitiveness of Tourism. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achsa, A.; Verawati, D.M.; Destiningsih, R.; Novitaningtyas, I. Competitive Advantage and Sustainable Tourism Balkondes at Borobudur Area Magelang Regency. Nusant. J. Bus. Manag. Appl. 2022, 7, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prameka, A.S.; Pradana, B.D.; Sudarmiatin, S.; Atan, R.; Wiraguna, T.R. The empowerment of public investment and smart management model for tourism villages sustainability. Advanece Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 193, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pundziene, P.; Nikou, S.; Bouwman, H. The nexus between dynamic capabilities and competitive firm performance: The mediating role of open innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, S. Measuring the sustainability performance of the tourism sector. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardika, I.W. Pustaka Budaya dan Pariwisata; Pustaka Larasan: Denpasar, Indonesia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R.M.; Speers, M.A.; McLeroy, K.; Fawcett, S.; Kegler, M.; Parker, E.; Wallerstein, N. Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a base for measurement. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Building Community Capacity for Tourism Development; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Damanpour, F.; Wischnevsky, D.J. Research on innovation in organizations: Distinguishing innovation-generating from innovation-adopting organizations. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2006, 23, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Kessler, E.H.; Scillitoe, J.L. Navigating the innovation landscape: Past research, present practice, and future trends. Organ. Manag. J. 2010, 7, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. Organizational complexity and innovation: Developing and testing multiple contingency models. Manag. Sci. 1996, 42, 693–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.A. Organizational innovation: Review, critique, and suggested research. J. Manag. Stud. 1994, 31, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strambach, S.; Surmeier, A. Knowledge dynamics in setting sustainable standards in tourism—The case of ‘Fair Trade in Tourism South Africa’. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 736–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranita, D. Membangun Kapabilitas dan Strategi Keberlanjutan Untuk Meningkatkan Keunggulan Bersaing Pariwisata Bahari Indonesia. J. Vokasi Indones. 2016, 4, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A.H. Central problems in the management of innovation. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguia, C. Product Innovation and the Competitive Advantage. Eur. Sci. J. 2014, 1, 140–157. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum (WEF). World Economic Forum, The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, A.; Beeton, R.; Pearson, L. Sustainable Tourism: An Overview of the Concept and its Position in Relation to Conceptualisations of Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setijawan, A. Pembangunan Smart Sustainable Tourism Village Dalam Perspektif Sosial Ekonomi. J. Planet Earth 2018, 3, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Widiati, I.A.P.; Permatasari, I. Strategi Smart Sustainable Tourism Village (Sustainable Tourism Development) Berbasis Lingkungan Pada Fasilitas Penunjang Pariwisata di Kabupaten Badung. Kertha Wicaksana Sarana Komun. Dosen Mhs. 2022, 16, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scholars | Similarity | Difference | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational Capability—Competitiveness | |||

| [81] Clustering analysis prioritization of automobile logistics services. Industrial Management and Data Systems | Researching the company’s capabilities and competitive advantages | The case study used is an automobile company | Four distinct producer groups were identified using a two-stage clustering approach. The cluster separates logistics preferences and outsourcing patterns from aftersales parts suppliers, original equipment service parts suppliers, original equipment manufacturers parts suppliers, and tier automakers. This paper finds that distribution and delivery services hold the highest percentage of outsourced services among manufacturers. |

| [82] A cluster concentration typology for making location decisions | Researching the company’s capabilities and competitive advantages | This study aims to examine location decisions from a macro perspective and utilize the findings for typology development | The resulting typology of cluster concentrations is based on four constructs identified in the literature: business innovation, specialization, complementarity, and knowledge transfer. This typology can serve as an aid in making these critical location decisions for practitioners as well as identifying future research topics for academics. |

| [83] 4th party logistics service providers and industrial cluster competitiveness: Collaborative operational capabilities framework | Researching the capabilities of tourist villages and their relationship to competitive advantage | The case study in this research is the service provider | The results show that total integration between 4PL and industrial clusters has not realized the potential for creativity business innovation and supply chain flexibility and they lack a competitive advantage when competing with other competitors. |

| Operational Capability—Sustainable Tourism Development | |||

| [84] Assessing Tourism Development from Sen’s Capability Approach | Examining the relationship between tourism village capability and smart sustainable tourism village | The research was conducted in Nicaragua and Costa Rica | The findings show that the capabilities of individuals and organizations can increase their ability to run a tourism business. |

| [16] Exploring the relationship between tourism and poverty using the capability approach | Examining the relationship between tourism village capability and smart sustainable tourism village | The research measures how capabilities can help society prosper | The findings show that participants appreciate the opportunities associated with monetary and non-monetary tourism resources and these opportunities help them achieve various aspects of well-being. |

| [17] Dynamic capability building and social upgrading in tourism—potentials and limits of sustainability standards | Examining the relationship between tourism village capability and smart sustainable tourism village | Integration using Global Value Chain (GVC) | The findings in this study are that the existence of the tourism village capability has a positive impact on the sustainability of the tourism business. |

| Competitiveness—Sustainable Tourism Development | |||

| [85] Sustainable Tourism of Destination, Imperative Triangle Among: Competitiveness, Effective Management, and Proper Financing | Examining the relationship between smart sustainable tourism village and competitive advantage | The dimension that is linked is with effective management and proper finance | The findings in this research aim to ensure that the competitive advantage of tourism products and services must be based on quality management; it becomes a way to ensure competitive advantage and, therefore, business market credibility. |

| [86] The significance of environmental values for destination competitiveness and sustainable tourism strategy making: insights from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area | Examining the relationship between the implementation of smart sustainable tourism village and competitive advantage | Another dimension that is measured is strategy making | The study found that visitors respond more negatively to the prospect of environmental degradation than to the prospect of a 20% increase in local prices; the detailed impact, however, depends on location and visitor mix. Clear seas, healthy coral reefs, healthy reef fish, and less trash are the four most important values. |

| Innovation—Performance | |||

| [87] Relationship between innovation and performance: impact of competitive intensity and organizational slack | Researching the relationship between innovation and performance on competitive intensity and organizational flexibility | The object of research is micro, small, and medium enterprises in Bogota, Colombia | Organizational slack and competitive advantage are relevant strategies to increase innovation and have a positive effect on organizational performance. |

| [88] Mohammad, I. N., Massie, J. D. D., and Tumewu. F, J. (2019). The effect of entrepreneurial orientation and innovation capability towards firm performances in small and medium enterprises | Examining the effect of operational capability and innovation capacity on company performance | The object of research is micro, small, and medium enterprises in Manado, North Sulawesi | Operational capability and innovation capability have a positive impact on company performance. |

| [53] The effect of entrepreneurial orientation, customer orientation, and knowledge sharing on innovation capability and business performance | Examining the effects of operational capabilities, customer orientation, and knowledge sharing on innovation capabilities and business performance | The object of research is micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the tourism sector in Banyuwangi Regency | This research proves that MSMEs related to the tourism sector in Banyuwangi must have a business concept, high creativity, be driven to take risks, be competitively aggressive, and be able to identify market opportunities to be competitively superior. MSMEs in the tourism sector in Banyuwangi must maintain their tourism village capabilities so they can continue to innovate in business. |

| [54] The role of coaching, capability, and innovation on the performance of SMEs in the Kenjeran Tourism Area in Surabaya | The role of training, capability, and innovation on performance | The object of this research is MSMEs in the tourist area of Kenje-ran, Surabaya | The results of the study show that business innovation influences the effect of capability on performance. Coaching, as an antecedent of capability, has a central role in improving the performance of MSMEs. The implication is that the government’s role in formulating coaching policies is needed to improve the performance of MSMEs in the economic development of tourism areas. |

| [89] To be or not to be digital, that is the question: Firm innovation and performance | Examining the relationship between organizational innovation and organizational performance | The objects of this research are digital and non-digital companies | This study shows that the profiling of entrepreneurs and managers and these leaders’ adoption of new digital processes contribute to a company’s greater competitive advantage. |

| Innovation—Competitiveness | |||

| [90] Global–local trajectories for regional competitiveness: Tourism innovation in the Western Cape | Researching the relationship between innovation and competitive advantage | The object of this research is the manager of tourist destinations in the Western Cape | The results of the investigation indicate a critical need for regional policies to focus on linking strategic networks to access global knowledge, as well as the need to develop tourism as a core regional competency and to strengthen the capacity of local institutions for regional business innovation, excellence competitiveness and economic growth in the Western Cape. |

| [91] Innovation and competitiveness in the context of the Bulgarian tourism industry | Research on the relationship between innovation and competitive advantage | The object of this research is the tourism industry in Bulgaria | Tourism development in Bulgaria must be based on business innovation, including the categories of product development, process management, and the internal or external relations of the organization. |

| [92] Competitiveness and innovativeness in the attractiveness of a tourist destination case study—tourist destination Oltenia | Examining the relationship between competitive advantage and innovation on the attractiveness of tourist destinations | The object of this research is a tourist destination in Oltenia | Conjunction conditions encourage environments that limit or affect competitive advantage in tourist destinations. |

| [93] Entrepreneurship, innovation and competitiveness: what is the connection? | Researches the relationship between entrepreneurship, innovation, and competitive advantage | This research covers many countries | The results show how the importance associated with entrepreneurship depends on the stage of economic development and can consequently reflect a positive or negative impact on these same strategies of economic growth. |

| Innovation—Performance | |||

| [94] Tourism competitiveness and tourism sector performance: Empirical insights from new data | Examining the relationship between competitive advantage and performance in the tourism sector | The object of this research is all companies in the tourism sector | This study suggests that, for countries around the world to promote the performance of the tourism sector, policymakers and stakeholders in the travel and tourism industry must pay sufficient attention to the improvement of TC and factor in the multidimensional nature of the relationship between TC and tourism performance within their policy framework. Provides appropriate policy recommendations for each region and country’s income group. |

| [95] Tourism destination competitiveness and tourism performance | Examining the relationship between the competitive advantage of tourist destinations and performance | The objects of this research are several countries in the world | This study confirms that core resources, complementary conditions, globalization, and tourism prices significantly explain tourism performance. The results show differences in the levels of competitive advantage and actual performance between countries, highlighting the specific limitations of the current TDC model and the reliability of the TTCI report. |

| [96] CSR Strategy in Technology Companies: Its Influence on Performance, Competitiveness and Sustainability | The influence of CSR strategy on company performance, competitive advantage, and sustainability | The object of this research is a company in the Science Technology Park in Spain | The results of the study show that CSR-oriented strategies make a significant contribution to organizational performance. In addition, CSR affects the competitive advantage of technology companies and, in particular, their sustainability. |

| Competitiveness—Capability—Performance—Excellence | |||

| [97] Pengaruh Kompetensi dan Kapabilitas Terhadap Keunggulan Kompetitif dan Kinerja Perusahaan | Excellence, capability, excellence, and performance | The unit of analysis is an accommodation company, not a tourist village | Competence and capability have a partially significant effect on competitive advantage. Competence, capability, and competitive advantage have a partially significant effect on company performance. |

| [98] Inovasi Organisasi dan Kinerja Organisasi: Studi Kasus dan Pusat Kajian dan pendidikan dan Pelatihan Aparatur III Lembaga Administrasi Negara | Innovation (technology, administration, and strategy) and organizational performance | The unit of analysis is Apparatus III of the State Administration Agency | Technology, administration, and strategy have a partially significant effect on company performance. |

| [99] Pengaruh Strategi Inovasi Terhadap Keunggulan Bersaing di Industri Kreatif (Studi Kasus UMKM Bidang Kerajinan Tangan di Kota Bandung) | Innovation and competitive advantage | The unit of analysis is MSMEs in the field of handicrafts in the city of Bandung | Business innovation has a significant effect on competitive advantage. |

| Variable | Item | r-Count | r-Table | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism Village Capability | 1 | 0.482 | 0.3 | Valid |

| 2 | 0.309 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| 3 | 0.571 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| Business Innovation | 1 | 0.667 | 0.3 | Valid |

| 2 | 0.586 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| 3 | 0.574 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| Competitive Advantage | 1 | 0.557 | 0.3 | Valid |

| 2 | 0.470 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| 3 | 0.629 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| 4 | 0.383 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | 1 | 0.718 | 0.3 | Valid |

| 2 | 0.606 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| 3 | 0.719 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| 4 | 0.734 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| Tourism Village Management Performance | 1 | 0.492 | 0.3 | Valid |

| 2 | 0.681 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| 3 | 0.706 | 0.3 | Valid | |

| 4 | 0.686 | 0.3 | Valid |

| No | Goodness of Fit Index | Cut-off Value | Results | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | χ2—Chi-Square | Expected small | 5562.167 | Bad fit |

| 2 | Significance Probability | ≥0.05 | 0.000 | |

| 3 | Degree of Freedom | >0 | 1422 | Bad fit |

| 4 | GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.625 | Bad fit |

| 5 | CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.736 | Bad fit |

| 6 | AGFI | ≥0.90 | 0.594 | Bad fit |

| 7 | TLI | ≥0.90 | 0.724 | Bad fit |

| 8 | CMIN/DF | ≤2.0 | 3.912 | Bad fit |

| 9 | RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.090 | Bad fit |

| No | Goodness of Fit Index | Cut off Value | Results | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | χ2—Chi-Square | Expected Small | 64,031 | Good fit |

| 2 | Significance Probability | ≥0.05 | 0.190 | |

| 3 | Degree of Freedom | >0 | 55 | Good fit |

| 4 | GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.974 | Good fit |

| 5 | CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.996 | Good fit |

| 6 | AGFI | ≥0.90 | 0.957 | Good fit |

| 7 | TLI | ≥0.90 | 0.994 | Good fit |

| 8 | CMIN/DF | ≤2.0 | 1.164 | Good fit |

| 9 | RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.021 | Good fit |

| No. | Variable | Indicator | Standard Loading | Standard Loading2 | Measurement Error (1-Standard Loading2) | Construct Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tourism Village Capability | TVC5 | 0.746 | 0.557 | 0.443 | 0.719 | 0.561 |

| TVC7 | 0.752 | 0.566 | 0.434 | ||||

| ∑ | 1.498 | 1.122 | 0.878 | ||||

| ∑2 | 2.244 | ||||||

| 2 | Business Innovation | BI4 | 0.768 | 0.590 | 0.410 | 0.800 | 0.571 |

| BI6 | 0.791 | 0.626 | 0.374 | ||||

| BI9 | 0.706 | 0.498 | 0.502 | ||||

| ∑ | 2.265 | 1.714 | 1.286 | ||||

| ∑2 | 5.130 | ||||||

| 3 | Competitive Advantage | CA6 | 0.785 | 0.616 | 0.384 | 0.705 | 0.545 |

| CA10 | 0.689 | 0.475 | 0.525 | ||||

| ∑ | 1.474 | 1.091 | 0.909 | ||||

| ∑2 | 2.173 | ||||||

| 4 | Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | SSTV2 | 0.743 | 0.552 | 0.448 | 0.798 | 0.590 |

| SSTV6 | 0.616 | 0.379 | 0.621 | ||||

| SSTV10 | 0.810 | 0.656 | 0.344 | ||||

| SSTV11 | 0.773 | 0.773 | 0.773 | ||||

| ∑ | 2.942 | 2.361 | 2.185 | ||||

| ∑2 | 8.655 | ||||||

| 5 | Tourism Village Management Performance | TVMP9 | 0.773 | 0.598 | 0.402 | 0.744 | 0.592 |

| TVMP11 | 0.766 | 0.587 | 0.413 | ||||

| ∑ | 1.539 | 1.184 | 0.816 | ||||

| ∑2 | 2.369 |

| Hypotheses | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Label | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | ← | Business Innovation | 0.326 | 0.117 | 2.778 | 0.005 | Accepted |

| H2 | Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | ← | Competitive Advantage | 0.267 | 0.172 | 1.555 | 0.120 | Not Accepted |

| H3 | Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | ← | Tourism Village Capability | 0.574 | 0.246 | 2.331 | 0.020 | Accepted |

| H4 | Tourism Village Management Performance | ← | Competitive Advantage | 0.662 | 0.177 | 3.525 | *** | Accepted |

| H5 | Tourism Village Management Performance | ← | Tourism Village Capability | 0.260 | 0.171 | 1.519 | 0.129 | Not Accepted |

| H6 | Tourism Village Management Performance | ← | Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | −0.425 | 0.293 | −1.452 | 0.146 | Accepted |

| H7 | Tourism Village Management Performance | ← | Business Innovation | 0.260 | 0.121 | 2.153 | 0.031 | Accepted |

| Standardized Direct Effects | Standardized Indirect Effects | Standardized Total Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive Advantage | → | Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | 0.433 | 0.433 | |

| Competitive Advantage | → | Tourism Village Management Performance | −0.379 | 0.318 | −0.061 |

| Business Innovation | → | Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | 0.270 | 0.270 | |

| Business Innovation | → | Tourism Village Management Performance | 0.255 | 0.199 | 0.454 |

| Tourism Village Capability | → | Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | 0.270 | 0.270 | |

| Tourism Village Capability | → | Tourism Village Management Performance | 0.311 | 0.199 | 0.510 |

| Smart Sustainable Tourism Village | → | Tourism Village Management Performance | 0.736 | 0.736 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amrullah; Kaltum, U.; Sondari, M.C.; Pranita, D. The Influence of Capability, Business Innovation, and Competitive Advantage on a Smart Sustainable Tourism Village and Its Impact on the Management Performance of Tourism Villages on Java Island. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914149

Amrullah, Kaltum U, Sondari MC, Pranita D. The Influence of Capability, Business Innovation, and Competitive Advantage on a Smart Sustainable Tourism Village and Its Impact on the Management Performance of Tourism Villages on Java Island. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914149

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmrullah, Umi Kaltum, Merry Citra Sondari, and Diaz Pranita. 2023. "The Influence of Capability, Business Innovation, and Competitive Advantage on a Smart Sustainable Tourism Village and Its Impact on the Management Performance of Tourism Villages on Java Island" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914149

APA StyleAmrullah, Kaltum, U., Sondari, M. C., & Pranita, D. (2023). The Influence of Capability, Business Innovation, and Competitive Advantage on a Smart Sustainable Tourism Village and Its Impact on the Management Performance of Tourism Villages on Java Island. Sustainability, 15(19), 14149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914149