Family SMEs in Poland and Their Strategies: The Multi-Criteria Analysis in Varied Socio-Economic Circumstances of Their Development in Context of Industry 4.0

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The growing importance of family enterprises in the global economy, the increased interest in them, the need to know the development mechanisms of such enterprises;

- The recognition of SME enterprises as an important factor in socio-economic growth in many countries of the world, including the EU. The study undertaken is therefore justified in the context of empirical science;

- The well-established role of business development strategy in strategic management theory, new concepts and models in response to dynamic civilizational change;

- The ongoing technological and organizational transformation of businesses. This includes the digitalization of products and services, machine-to-device-to-human communication, personalization of products and services (cf. Industry 4.0).

- Clarify the essence and the specificity of family businesses;

- Show the changes in the development processes of family businesses in the context of Industry 4.0 on the basis of literature research (secondary, qualitative research);

- Create the methodology of the research carried out;

- Present the results of our own empirical research (primary, quantitative research) related to the implementation of strategies among micro, small and medium-sized family enterprises in various socio-economic conditions (before and during the COVID-19 pandemic);

- Verify the adopted research hypotheses and present conclusions and recommendations, concluding the process of research knowledge.

- Stage 1: Creating the authors’ own research methodology, including qualitative and quantitative research methods.

- Stage 2: Analysis of the literature on the subject, allowing the achievement of theoretical objectives regarding the specificity of the activities of family enterprises, as well as showing changes in the development processes of family enterprises in the context of the conditions of Industry 4.0.

- Stage 3: Description and presentation of research results, verification of research hypotheses, as well as presentation of conclusions and recommendations.

2. The Theoretical Basis of the Research

2.1. The Family Business—The Essence and Concept

- A prudent and more efficient financial policy compared to other enterprises. Family-owned establishments are generally less indebted (e.g., due to their reluctance to take out loans, as well as difficulties in meeting bank requirements for debt servicing capacity) [35];

- Frequently positioning themselves in market niches, realizing non-standard goods and services [36];

- Involvement of employees (including non-family members) in the company’s goals and their emotional attachment to the company [39].

2.2. Business Development in Industry 4.0

- All movement always involves the functioning and change in an object;

- Development is a type of movement that produces not only quantitative but also appropriately directed qualitative changes in an object;

- If the changes go in the desired direction, one speaks of progressive development. If the changes move away from the desired state, it is to be referred to as regressive development;

- If there is no change at all in the facility, one should speak of stagnation [53].

- A new management model based on strong technological/analytical capabilities and flexible organizational structures;

- More accurate and faster market intelligence. The time to market for new products is forecast to shorten by 20–50%, depending on the specific industry and country’s economy;

- Availability of low-cost public cloud services and reduction in barriers to entry;

- Precisely meeting the expectations of individual online customers at every stage of product design and implementation. Developing individual and niche products, creating new business models;

- Designing and manufacturing products so that they can be easily reused (cf. the concept of the circular economy);

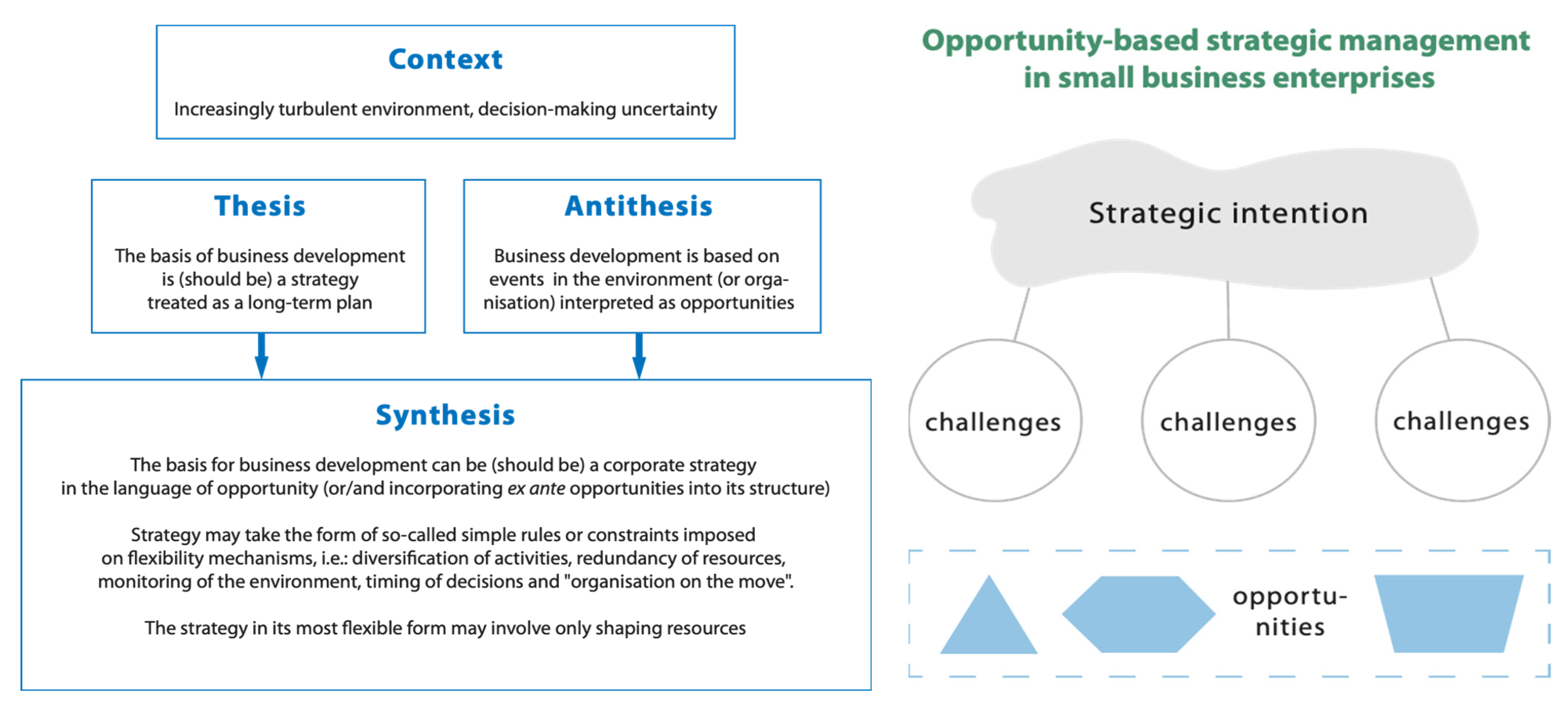

2.3. Development Strategies of the Family Business in the SME Sector

3. Materials and Methods

- Qualitative methods: (a) a critical analysis of existing explanations of the concept and essence of family enterprises; (b) a review of the literature on the determinants of enterprise development in the light of Industry 4.0. The application of qualitative methods allowed development of an author’s frame of the context of development of family enterprises of the SME sector in the perspective of Industry 4.0;

- Quantitative methods: (a) a taxonomy analysis of structures based on the similarity index (SI) of the surveyed structures; (b) a comparative analysis using cross-tabulations explaining the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

- Object scope of the research: the strategies implemented by the surveyed units during the adopted research periods, including their type, nature and planning;

- Subject scope of the research: 130 family businesses surveyed, including 88 micro-, 22 small and 20 medium-sized enterprises;

- Spatial scope: the Masovian Voivodeship, one of the most economically developed areas of Poland. The choice was dictated by the largest number of family businesses in the SME sector in this province of Poland [87]. There are more than 2 million family businesses in Poland, which generate up to 72% of GDP and provide about 8 million job positions [88];

- Temporal scope: the research was conducted between 23 January 2023 and 6 February 2023. It considers two socio-economically differentiated periods: the time preceding the COVID-19 pandemic (2018–2019) and the period of its duration (2020–2021).

- They declared themselves as family-owned entities. These are businesses where: at least two members of the owners’ family or related person work; at least one of them has a say in management; the family or related persons own over 50% of the business;

- Belong to the SME sector. Micro-enterprise has <10 employees, turnover and/or total annual balance sheet does not exceed €2 million. A small enterprise has <50 employees, turnover and/or annual balance sheet total does not exceed €10 million. A medium-sized enterprise has <250 employees, a turnover not exceeding €50 million and/or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding €43 million;

- Have performed service activities, have been operating on the economic market at least since 2018, have their registered office in the Mazowieckie Voivodeship.

4. Empirical Results of the Research

4.1. Development Strategies in the Family Enterprises in the SMEs Sector in Poland

4.2. Specifics of the Development Strategies of Family SMEs in Poland in the Period before and during COVID-19 Pandemic

4.3. Changes in the Strategies of SMEs in the Periods 2018–2019 and 2020–2021

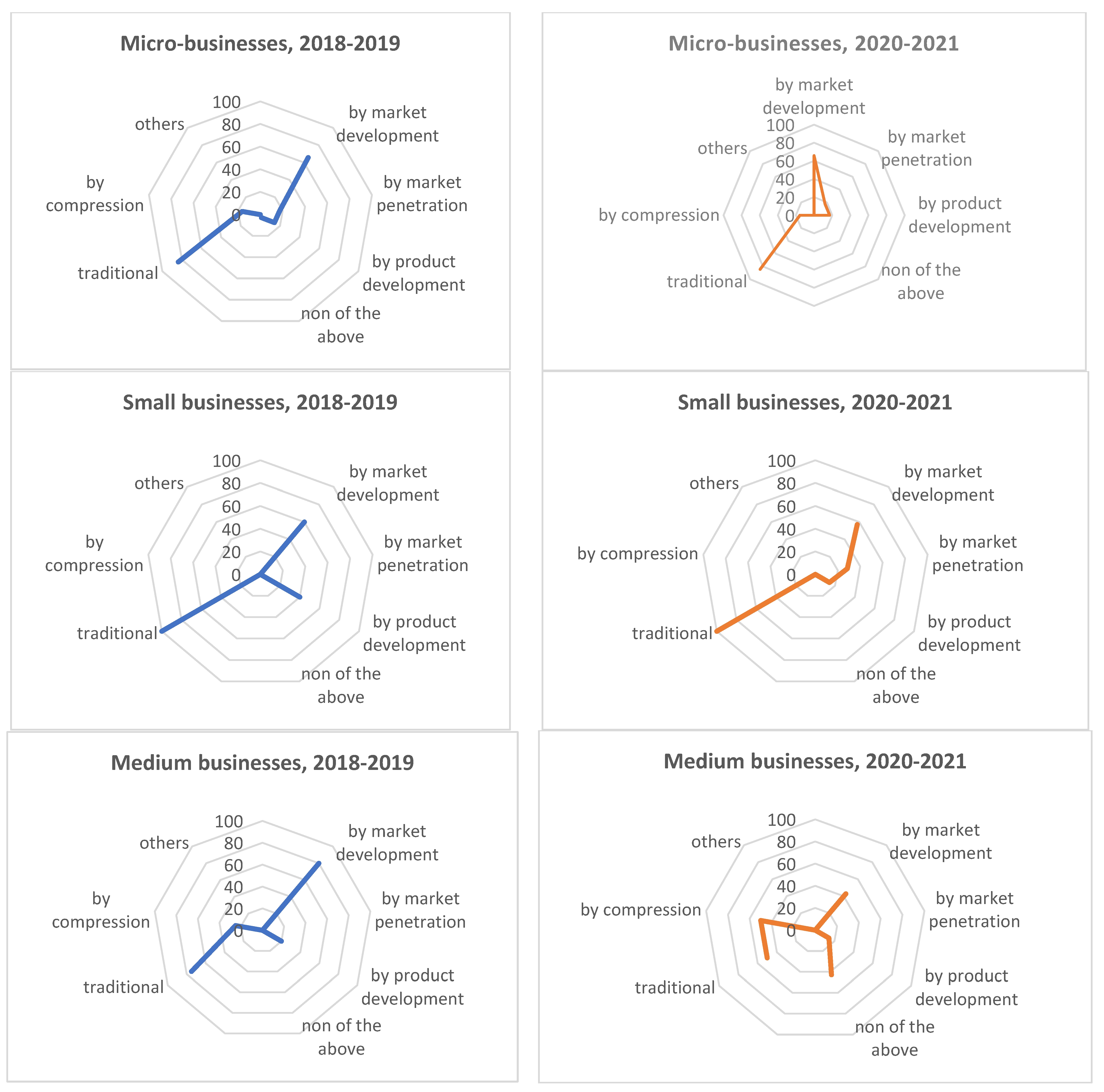

- Expansive development strategies implemented by: (a) market development (searching for new consumers or new markets for the products held); (b) market penetration (striving to increase sales of products already offered on existing markets); (c) product development (creating modernized products to meet the needs of existing markets);

- Other development strategies involving: (a) traditional competition strategies such as quality leadership, cost leadership, concentration (focusing on a selected market segment), external and internal diversification; (b) conservative-compression approach (conservative strategy, corrective strategy and defensive strategy); (c) other strategies indicated by respondents. Traditional competition strategies such as cost leadership, differentiation and concentration can be used simultaneously, although this practice is rather rarely used [90].

5. Conclusions

- The literature base: The analysis of the literature on the subject revealed the dependance between strategic management in family enterprises in the SME sector, adopted organizational culture and professed values in these entities. Growth planning here is long-term in nature, not based solely on profits but on sustainable development, where it is often the intention of the owner(s) to pass the business on to the next generation. This is reflected in the strategic planning and approach to new technologies and their implementation in family businesses;

- Management styles: As far as company management style is concerned, about 92% of Polish SMEs showed the influence of family on management (95–99% in micro- and small enterprises, 80% in medium-sized ones). An issue that requires further research is the influence of the company’s management style on the development strategies applied;

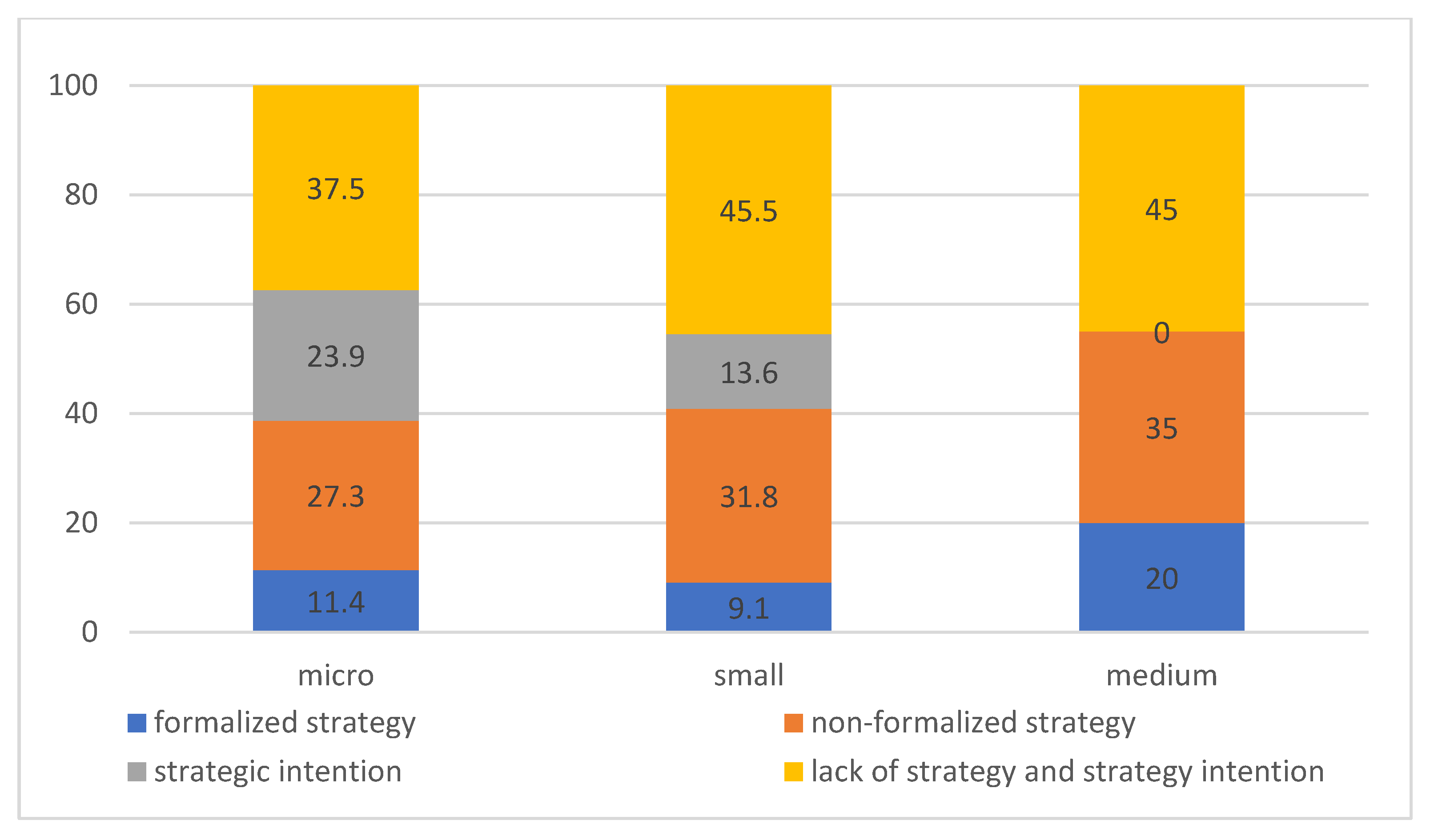

- Presence of development strategy: A significant proportion of family enterprises in the SME sector do not have a development strategy, nor do they pursue a so-called strategic intention. The research shows that only 60% of family enterprises have a strategy of any kind: 12.3% have a formalized strategy, 29.2% have a non-formalized strategy, and the remaining 18.5% only have a strategic intent. The highest number of enterprises with a formalized strategy was recorded among medium-sized entities (20%). In the case of micro and small enterprises, the figures are 11.4% and 9.1% respectively;

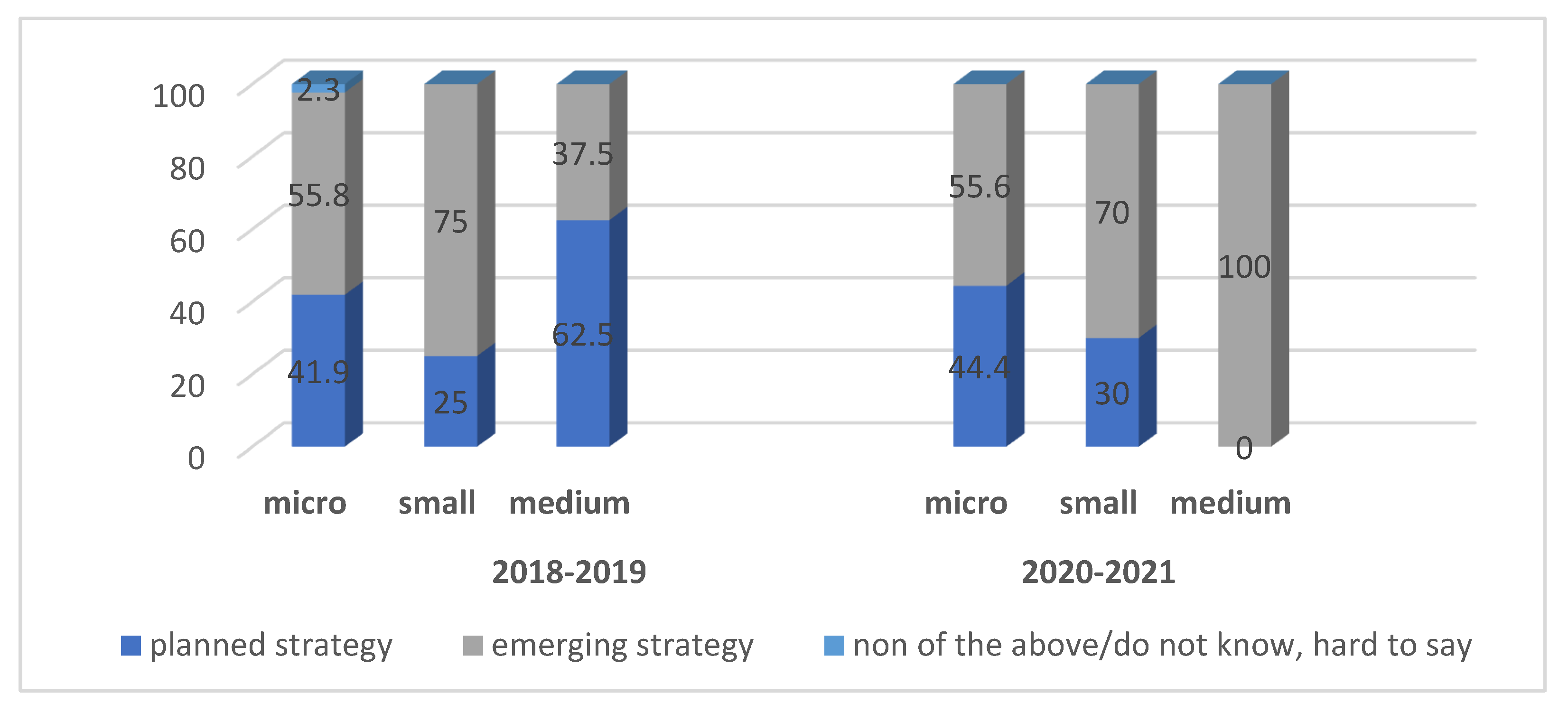

- Pandemic-driven strategy changes: During the pandemic, the share of SMEs pursuing expansive strategies decreased, while the share of those pursuing conservative-compressive strategies increased. Before the pandemic, about 56% of family establishments followed an emergent strategy, and nearly 43% followed a planned strategy. During the pandemic, these numbers were 75% and 25%, respectively. In the two study periods, there is a clear differentiation between medium-sized, small and micro-enterprises in terms of the growth strategies they used. For example, although medium-sized enterprises are characterized by the most advanced management systems among family-run SMEs and the use of advanced competitive techniques and methods, they took a wait-and-see approach during the pandemic. As far as micro-enterprises are concerned, the pandemic did not substantially affect their strategies. In both study periods, an emergent strategy prevailed among them (55.8% and 55.6% respectively);

- Development strategy and innovation: There is a positive relationship between the implementation of a development strategy in family businesses in the SME sector and their innovation activity, which is in line with Industry 4.0 trends. The research showed that businesses declaring any strategy were more likely to use innovation than those that did not have a strategy. As many as 82.1% of SMEs that had a development strategy showed innovation activity. However, only 17.9% of the enterprises without any strategy were implementing innovations. The share of enterprises with no strategy and no innovative activity was as high as 61.9%. It is noteworthy that the innovative approach in family businesses implementing development strategies managed to remain at a similar level of activity during the analyzed periods. This confirms the thesis that the implementation of a development strategy is the basis for the realization of innovation and can be an important factor in building a competitive advantage.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Basly, S. (Ed.) Family Businesses in the Arab World; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- de Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Majocchi, A.; Piscitello, L. Family Firms in the Global Economy: Toward a Deeper Understanding of Internationalization Determinants, Process and Outcomes. Glob. Strategy J. 2018, 8, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, F.; Lank, A.G. The Family Business: Its Governance for Sustainability; McMillan Press LTD: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V.K.; Pieper, T.M.; Hair, J.F., Jr. The Global Family Business: Challenges and Drivers for Cross-Border Growth. Bus. Horiz. 2012, 55, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, I.; Kotlar JRavasi, D.; Vaara, E. Dealing with revered past: Historical identity statements and strategic change in Japanese family firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 590–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewska-Bielawska, A. Strategie Rozwoju Przedsiębiorstw: Nowe Spojrzenie; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczewska, K. Przedsiębiorstwa Rodzinne. Specyfika Modeli Biznesu; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Noga, A. Teorie Przedsiębiorstw; PWE: Warszawa, Polnad, 2009; pp. 218–244. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Sharma, P. Defining the family business by behaviour. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 23, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułkowski, Ł.; Sułkowska, J.; Marjański, A. Entrepreneurship of Family Businesses in the European Union. In Doing Business in Europe: Economic Integration Processes, Policies, and the Business Environment; Dima, A.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortman, M.S. Theoretical foundations for family-owned business. A conceptual and research—Based paradigm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1994, 1, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelly, R.G. The family business. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1964, 42, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.G. Examining the Family Effect on Firm Performance. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frishkoff, P.A. Understanding Family Business: What is a Family Business? Oregon State University: Austin, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, R.; Jaskiewicz, P. Managing Traditions: A Critical Capability for Family Business Success. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2020, 33, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H.; Shanker, M.C. Family businesses’ contribution to the U.S. Economy. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2003, 16, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli, A. The History of Family Business 1850–2000; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Flören, R.; Uhlaner, L.; Berent-Braun, M. Family Business in the Netherlands: Characteristics and Success Factor. In A Report for the Ministry of Economic Affairs; Nyenrode Business Universiteit: Breukeler, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zellweger, T. Managing the Family Business: Theory and Practice; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Northampton, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, A.; Więcek-Janka, E.; Hadryś-Nowak, A.; Wojewoda, M.; Klimaek, J. Model 5 Poziomów Definicyjnych Firm Rodzinnych. Podstawy Metodyczne i Wyniki Badań Firm Rodzinnych w Polsce; Instytut Biznesu Rodzinnego: Poznań, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Astrachan, J.; Klein, S.; Smyrnios, K. The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal to solving the family business definition problem. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Q.J. Keep the Family Baggage out of the Family Business; A Fireside Book; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Firmy Rodzinne w Polskiej Gospodarce—Szanse i Wyzwania; Kowalewska, A. (Ed.) PARP: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lansberg, I. Suceeding Generations; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stawicka, E. Firmy rodzinne jako prykład przedsiębiorstw zarządzanych przez wartości, ich sens i znaczenie. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW W Warszawie—Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2010, 25, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Firmy Rodzinne—Współczesne Wyzwania Przedsiębiorczości Rodzinnej; Kierunki i Strategie Rozwoju; Sułkowski, Ł. (Ed.) Społeczna Akademia Nauk: Łódź, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, D.; Englisch, P. The Values Effect: How to Build a Lasting Competitive Advantage through Your Values and Purpose in a Digital Age; Global Family Business Survey; PwC: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, I.; Rondi, E.; De Massis, A. Managing the tradition and innovation paradox in family firms: A family imprinting perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44, 20–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Kotlar, J.; Messeni-Petruzzelli, A.; Wright, M. Innovation through tradition: Lessons from innovative family businesses and directions for future research. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 30, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strike, V.M.; Berrone, P.; Sapp, S.G.; Congiu, L. A socioemotional wealth approach to CEO career horizons in family firms. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 555–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.D. Historical Overview of Family Firms in the United States. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1988, 1, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Brigham, K.H. Long-term orientation and intertemporal choice in family firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 1149–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, P.; Rocha, H. On the goals of family firms: A review and integration. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2018, 9, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.M.; Nason, R.S.; Nordqvist, M.; Brush, C.G. Why do family firms strive for nonfinancial goals? An organizational identity perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, J.; Wyzuj, A. Charakterystyka finansowa firm rodzinnych. Deb. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Bank. 2015, 15, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sobiecki, R.; Kargul, A.; Kochanowska, J. Przedsiębiorstwo rodzinne—Definicje i stan wiedzy. In Przedsiębiorstwo Rodzinne w Gospodarce Globalnej; Sobiecki, R., Ed.; SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrò, A.; McGinnes, T. (Eds.) Mastering a Comeback: How Family Businesses Are Triumphing over COVID-19; KPMG: Hong Kong, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, T. Family Business and Its Longevity. Kindai Manag. Rev. 2014, 2, 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewska, M. Zaangażowanie Pracowników Jako Czynnik Wspomagający Konkurencyjność Przedsiębiorstwa. Available online: www.linkedin.com/in/monika-olszewska-phd/recent-activity/articles (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Firmy Rodzinne—Determinanty Funkcjonowania i Rozwoju. In Współczesne Aspekty Zarządzania; Sułkowski, Ł. (Ed.) Społeczna Akademia Nauk: Łódź, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, S.B. Family Business in Germany: Significance and Structure. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2000, 3, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawko, M. Finansowanie i struktura kapitałowa przedsiębiorstw rodzinnych. Kwart. Nauk. O Przedsiębiorstwie 2019, 2, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, R.A. Two sides of a one-sided phenomenon: Conceptualizing the family business and business family as a Möbius strip. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 3, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedbała, E. Firmy rodzinne—Obiekt badawczy. Master Bus. Adm. 2002, 5, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Więcek-Janka, E. Wiodące Wartości w Zarządzaniu Przedsiębiorstwami Rodzinnymi; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Poznańskiej: Poznań, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżak, J. Rozwój przedsiębiorczości rodzinnej w Polsce na tle tendencji światowych. Przegląd Organ. 2016, 4, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Overview of Family—Business—Relevant Issues: Research, Networks, Policy Measures and Existing Studies; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Firma w Rodzinie Czy Rodzina w Firmie. Metodologia Wsparcia Firm Rodzinnych; Bryczkowska, K.; Olszewska, M.; Mączyńska, M. (Eds.) Polska Agencja Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rejer, A. Kongres Firm Rodzinnych 2020; Forbes: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2020; p. 17. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Handler, W. Methodological issues and consideration in studying family business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 2, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagiuri, R.; Davis, J.A. Bivalent Attributes of the Family Firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1996, 9, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrusewicz, W. Planowanie Rozwoju Przedsiębiorstw Przemysłowych; TNOIK: Poznań, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chomątowski, S. Rozwój Przemysłu w Świecie; Akademia Ekonomiczna w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Machaczka, J. Zarządzanie Rozwojem Organizacji. In Czynniki, Modele, Strategia, Diagnoza; PWN: Warszawa, Poland; Kraków, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Górka, K.; Łuszczyk, M.; Thier, A. Przejawy oraz skutki IV i V rewolucji przemysłowej w rozwoju społeczno-gospodarczym. In Gospodarka i Megatrendy Rozwoju Współczesnego Świata; Kwiatkowski, E., Ed.; PTE: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; pp. 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Siuta-Tokarska, B.; Thier, A. Progress in the implementation of the 4th and 5th industrial revolution and artificial intelligence. In Industry 4.0. A Glocal Perspective; Duda, J., Gąsior, A., Eds.; Routladge Studies in Management, Organizations and Society: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. Industry 4.0: Digitalisation for Productivity and Growth; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, P. Wizja przemysłu nowej generacji—Perspektywa dla Polski. Czwarta rewolucja przemysłowa. Państwo I Społeczeństwo 2018, 3, 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Dizikes, P. Should We Tax Robots? Available online: https://news.mit.edu/2022/robot-tax-income-inequality-1221 (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Nawrocka, E. Bezwarunkowy Dochód Podstawowy; Kancelaria Senatu: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.L. The special role of strategic planning for family businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1988, 1, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.L. Perpetuating the Family Business; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Donckels, R.; Fröhlich, E. Are family business really different? European Experiences from STRATOS. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1991, 2, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P. Ambitions, External environment and strategic factor differences between family and non-family companies. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1997, 9, 127–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlock, R.S.; Ward, J.L. Strategic Planning for the Family Business: Parallel Planning to Unify the Family and Business; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2001; p. 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H. Strategic Management of the Family Business: Past Research and Future Challenges. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1997, 10, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.; Martinez, J.L.; Ward, J.L. Is strategy different for the family-owned businesses? Fam. Bus. Rev. 1994, 7, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułkowski, Ł. Concept of organizational identity in family business. Przedsiębiorczość I Zarządzanie 2013, 14, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Stabryła, A. Zarządzanie Strategiczne w Teorii i Praktyce Firmy; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shaulska, L.; Shevchenko, T.; Kovalenko, S.; Allayarov, S.; Sydorenko, O.; Sukhanova, A. Strategic enterprise competitiveness management under global challenges. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Łobos, K.; Sus-Januchowska, A. Zarządzanie strategiczne: Małe versus duże przedsiębiorstwa, Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu. Zarządzanie Strateg. W Badaniach Teoretycznych I W Prakt. 2008, 20, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Borowiecki, R.; Siuta-Tokarska, B.; Janas, M.; Kruk, S.; Krzemiński, P.; Thier, A.; Żmija, K. The Competitive Position of Small Business Furniture Industry Enterprises in Poland in the Context of Sustainable Management: Relationships, Interdependencies, and Effects of Activities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeboom, L. Application of Systems Theory in Business Organizations. Available online: https://smallbusiness.chron.com/application-systems-theory-business-organizations-73405.html (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Piekarczyk, A.; Zimniewicz, K. Myślenie Systemowe w Teorii i Praktyce; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepan-Jakubowska, D. Podejście systemowe do problematyki firmy rodzinnej. In Firma w Rodzinie Czy Rodzina w Firmie. Metodologia Wsparcia Firm Rodzinnych; PARP: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wysokińska-Senkus, A. Doskonalenie Systemowego Zarządzania w Kontekście Sustainability; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rybicki, J. Podejście holistyczne w zarządzaniu strategicznym. Pract. Nauk. WSZiP Wałbrzychu 2012, 17, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, G.G.; Fa, M.C.; Pasola, J.V. Using environmental management systems to increase firms’ competitiveness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2003, 10, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Galunic, D.C. Coevolving: At last, a Way to Make Synergies Work. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dettori, A.; Floris, M. Facing COVID-19 challenges: What is so special in family businesses? TQM J. 2022, 34, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. 2007. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/Klasyfikacje/doc/pkd_07/pkd_07.htm (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Janecki, J. Ocena konsekwencji kryzysu pandemicznego COVID-19 w sektorze polskich przedsiębiorstw. Stud. Biura Anal. Sejm. BAS 2022, 69, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmy w Dobie COVID-19. Wyniki Badania; Navigator Capital Group: Warszawa, Poland, 2020.

- Siuta-Tokarska, B. SMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. The Sources of Problems, the Effects of Changes, Applied Tools and Management Strategies—The Example of Poland. Sustainability 2021, 18, 10185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubalcaba, L. Business services in European economic growth. Strateg. Dir. 2012, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, A. Productivity Growth, Efficiency and Outsourcing in Manufacturing and Service Industries. J. Econ. Surv. 2003, 17, 79–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Działalność Przedsiębiorstw Niefinansowych w 2021 r.; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2022.

- Wielkopolski Fundusz Rozwoju. Available online: www.wfr.org.pl/blog/2022/03/21/firmy-rodzinne-wazny-i-trwaly-element-pejzazu-zycia-gospodarczego (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Banaszyk, P.; Gorynia, M. Pandemia COVID-19 a konkurencyjność przedsiębiorstwa. ICAN Manag. Rev. 2020, 4, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rymarczyk, J. Strategie Konkurencji Przedsiębiorstwa Międzynarodowego, Challenges of the Global Economy; Working Papers; Institute of International Business University of Gdańsk: Gdańsk, Poland, 2012; Volume 31, pp. 573–584. [Google Scholar]

| Specifics | Company Size Class | SME | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | Small | Medium | ||

| Share, % | ||||

| Number of Business Owners/Co-Owners | ||||

| 1 | 61.4 | 45.5 | 25.0 | 53.1 |

| 2–3 | 38.6 | 54.5 | 70.0 | 46.2 |

| 4–5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.8 |

| Structure similarity index (SI) | SImic/sm = 0.0 | |||

| SIsm/med = 0.05 | ||||

| SIsm/med = 0.05 | ||||

| Legal Form | ||||

| Self-employed natural person | 62.5 | 40.9 | 0.0 | 49.2 |

| Private partnership/civil law partnership | 25.0 | 36.4 | 5.0 | 23.8 |

| General partnership | 1.1 | 22.7 | 30.0 | 9.1 |

| Limited partnership | 2.3 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 3.1 |

| Limited joint-stock partnership | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.8 |

| Limited liability company | 9.1 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 13.8 |

| Structure similarity index (SI) | SImic/sm = 0.0 | |||

| SIsm/med = 0.0 | ||||

| SIsm/med = 0.0 | ||||

| Management and Leadership Styles | ||||

| Centralization of management (owners manage the business themselves; patriarchal/autocratic management style) | 42.0 | 50.0 | 45.0 | 44.6 |

| Decentralization of management (management is influenced by other family members and/or external managers; democratic or liberal style) | 58.0 (53.0 *) | 50.0 (41.0 *) | 55.0 (30.0 *) | 54.6 (46.9 *) |

| Structure similarity index (SI) | SImic/sm = 0.92 | |||

| SIsm/med = 0.95 | ||||

| SIsm/med = 0.87 | ||||

| Development Strategies for the Period 2018–2021 | Have Innovative Measures Been Applied between 2018 and 2021? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NOT | In Total | ||||

| Number of Companies | % | Number of Companies | % | Number of Companies | % | |

| without a change in strategy | 25 | 37.3 | 10 | 15.9 | 35 | 26.9 |

| change in strategy | 30 | 44.8 | 14 | 22.2 | 44 | 33.8 |

| no strategy of any kind | 12 | 17.9 | 39 | 61.9 | 51 | 39.2 |

| in total | 67 | 100.0 | 63 | 100.0 | 130 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siuta-Tokarska, B.; Juchniewicz, J.; Kowalik, M.; Thier, A.; Gross-Gołacka, E. Family SMEs in Poland and Their Strategies: The Multi-Criteria Analysis in Varied Socio-Economic Circumstances of Their Development in Context of Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914140

Siuta-Tokarska B, Juchniewicz J, Kowalik M, Thier A, Gross-Gołacka E. Family SMEs in Poland and Their Strategies: The Multi-Criteria Analysis in Varied Socio-Economic Circumstances of Their Development in Context of Industry 4.0. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914140

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiuta-Tokarska, Barbara, Justyna Juchniewicz, Małgorzata Kowalik, Agnieszka Thier, and Elwira Gross-Gołacka. 2023. "Family SMEs in Poland and Their Strategies: The Multi-Criteria Analysis in Varied Socio-Economic Circumstances of Their Development in Context of Industry 4.0" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914140

APA StyleSiuta-Tokarska, B., Juchniewicz, J., Kowalik, M., Thier, A., & Gross-Gołacka, E. (2023). Family SMEs in Poland and Their Strategies: The Multi-Criteria Analysis in Varied Socio-Economic Circumstances of Their Development in Context of Industry 4.0. Sustainability, 15(19), 14140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914140