How to Promote a Destination’s Sustainable Development? The Influence of Service Encounters on Tourists’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

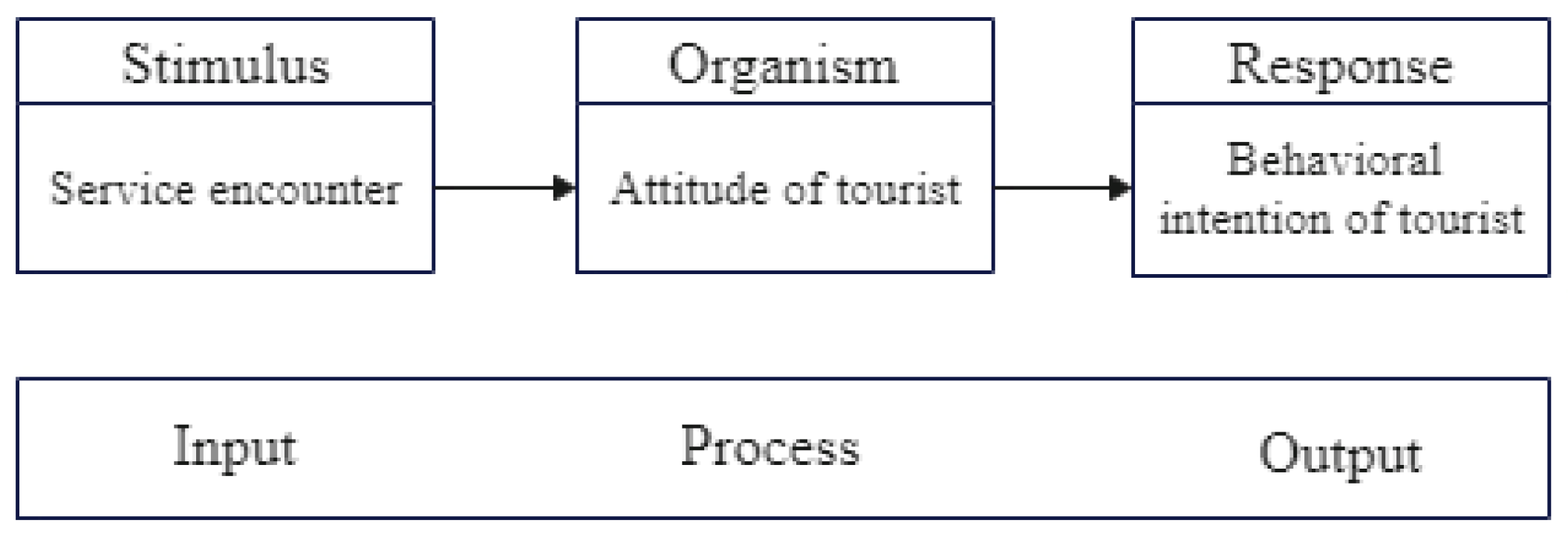

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Model

2.2. Service Encounter

2.3. Attitude

2.4. Behavioral Intention

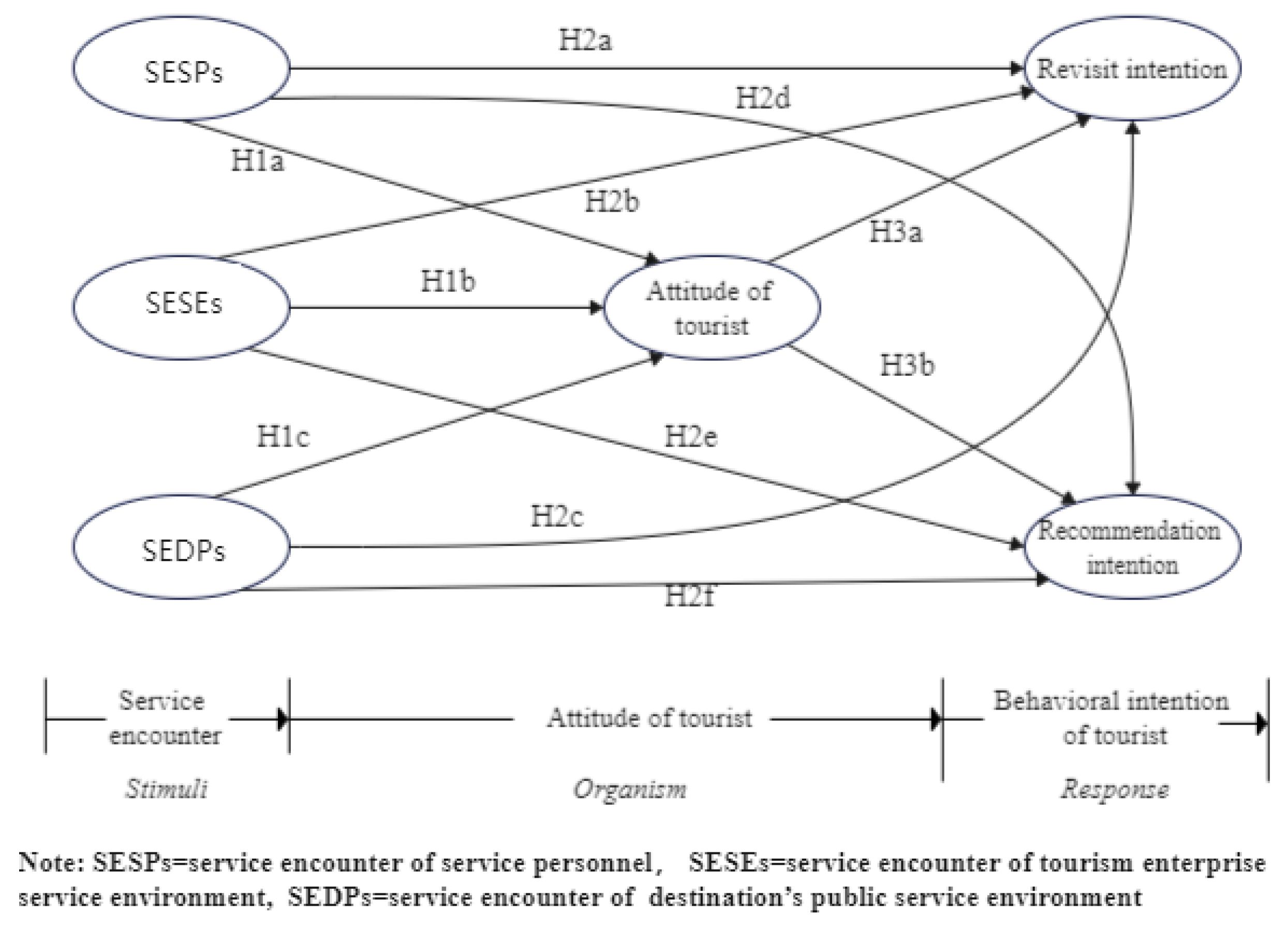

2.5. The Relationships among Service Encounters and Tourists’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions

2.5.1. The Relationship between Service Encounters and Tourists’ Attitudes

2.5.2. The Relationship between Service Encounters and Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions

2.5.3. The Relationship between Tourists’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Reliability and Validity of the Questionnaire

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. The Results of Reliability and Validity Testing

4.3. The Results of EFA

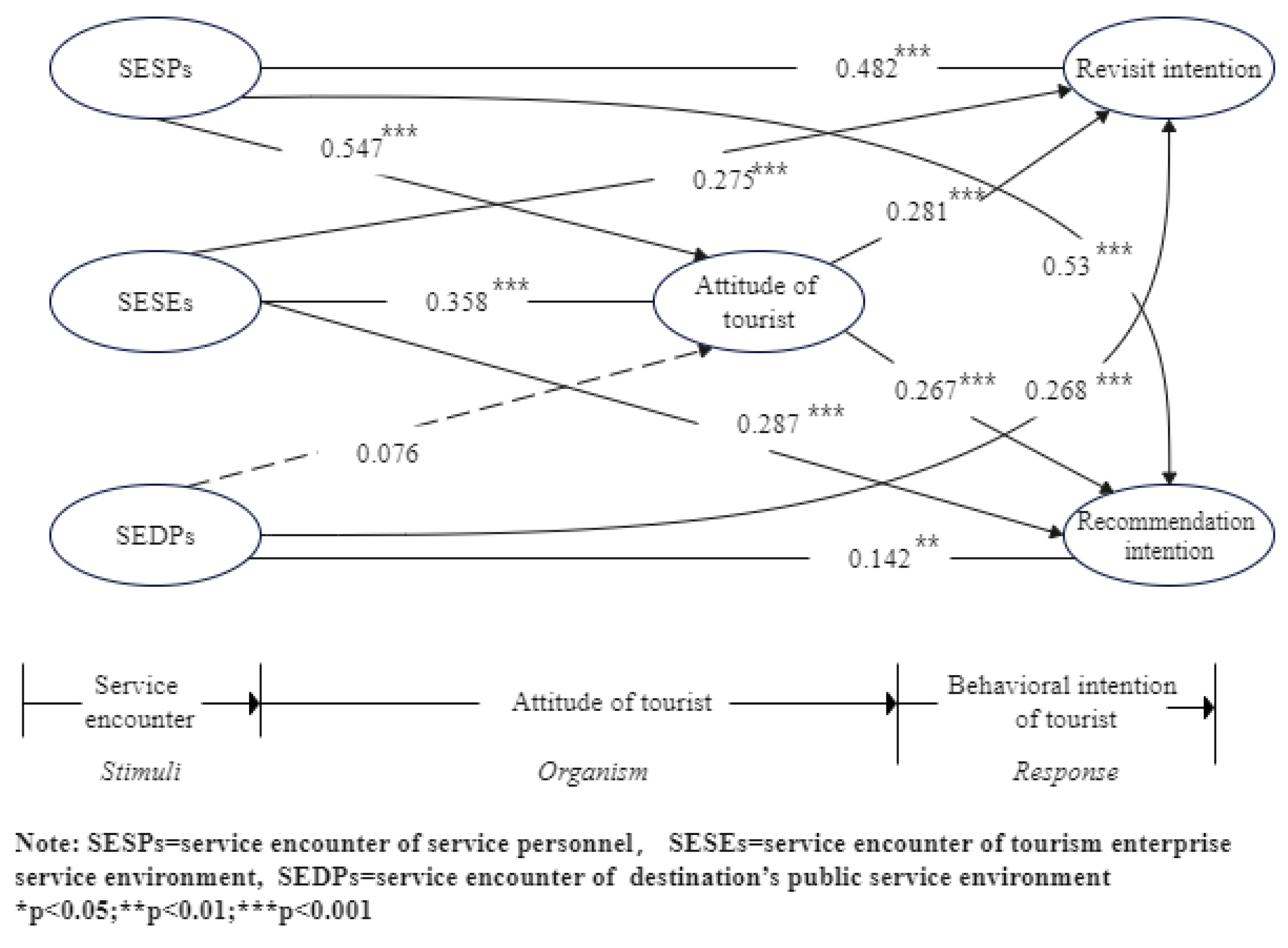

4.4. The Results of Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| SESPs | The employees are friendly to me. | Brady, M.K. and Cronin, J.J. (2001) [77] |

| The employees are willing to help me. | ||

| I can see from the employees’ attitudes that they understand my needs. | ||

| The employees know their jobs well. | ||

| The employees can answer my questions quickly. | ||

| The employees can use their knowledge to meet my needs. | ||

| The employees undertake actions to address my needs. | ||

| The employees give quick responses to my needs. | ||

| I can see from the employees’ behavior that they understand my needs | ||

| SESEs | The enterprises have a pleasant smell. | Hightower, R., Jr. et al. (2002) [78] |

| The lighting is excellent in the enterprises. | ||

| The enterprises are clean. | ||

| The temperature in the enterprises is pleasant. | ||

| The background music is appropriate. | ||

| The background noise level in the enterprises is acceptable. | ||

| The enterprises have more than enough space for me to be comfortable. | ||

| The physical facilities in the enterprises are comfortable. | ||

| The enterprises’ interior layout is pleasing. | ||

| The signs used (i.e., bathroom, enter, exit, smoking) in enterprises are helpful to me. | ||

| The restrooms are appropriately designed. | ||

| The parking lot has more than enough space. The color scheme is attractive. The materials used inside the enterprises are pleasing and of high quality. The architecture is attractive. The style of the interior accessories is fashionable. | ||

| SEDPs | The destination is clean. | Zhou, M.F. et al. (2019) [2] |

| The air in the destination is fresh. | ||

| The destination has a pleasant landscape. | ||

| The destination has good public security. | ||

| The urban planning of the destination is reasonable. | ||

| The human landscape is in harmony with the natural landscape | ||

| The public facilities (toilets, waste containers, rest facilities, safety facilities) are more than enough. | ||

| The public facilities (transportation, toilets) are comfortable | ||

| The public facilities (toilets, rest facilities) are clean. | ||

| The public facilities (transportation, toilets, safety facilities, tourism public information) are convenient. | ||

| The destination has smooth traffic. | ||

| The public facilities (transportation, trash can) are unique. | ||

| The public facilities (toilets, rest facilities) are not damaged. | ||

| The destination uses informatization and intelligent facilities (application, virtual reality, augmented reality, interactive facilities, etc.). | ||

| Attitude | Guilin leaves a good impression | Reitsamer, B.F. et al. (2016) [38] |

| Guilin is satisfactory to me | ||

| Guilin leaves a positive impression | ||

| I like Guilin | ||

| Revisit | I hope to visit this site again | Bayih, B.E. and Singh, A. (2020) [61] |

| I desire to revisit this destination | ||

| I plan to revisit this site | ||

| Recommendation | I will speak positive things about this site to others | |

| I will release positive information on social media | ||

| I will recommend this site to others |

References

- Kim, S.S.; Prideaux, B. An investigation of the relationship between South Korean domestic public opinion, tourism development in North Korea and a role for tourism in promoting peace on the Korean peninsula. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, F.; Wang, K. Destination Service Encounter Modeling and Relationships with Tourist Satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable-A Guide for Policy Makers (English Version); World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Paunović, I.; Dressler, M.; Mamula Nikolić, T.; Popović Pantić, S. Developing a competitive and sustainable destination of the future: Clusters and predictors of successful national-level destination governance across destination life-cycle. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; An, H.; Peng, L.; Zhou, H.; Hu, F. Has China’s low-carbon strategy pushed forward the digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises? Evidence from the low-carbon city pilot policy. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 102, 107184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C. Integrated concepts of the UTAUT and TPB in virtual reality behavioral intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Lai, Y.-H.R.; Petrick, J.F.; Lin, Y.-H. Tourism between divided nations: An examination of stereotyping on destination image. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Cui, M. The role of co-creation experience in forming tourists’ revisit intention to home-based accommodation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. J. Bus. Ventur. 1977, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Larivière, B.; Bowen, D.; Andreassen, T.W.; Kunz, W.; Sirianni, N.J.; Voss, C.; Wünderlich, N.V.; De Keyser, A. “Service Encounter 2.0”: An investigation into the roles of technology, employees and customers. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-López, P.E.; Cárcamo-Solís, M.d.L.; Álvarez-Castañón, L.; Guzmán-López, A. Impact of training on improving service quality in small provincial restaurants. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2017, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. Studying factors influencing repeat visitation of cultural tourists. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.; Hanlan, J.; Wilde, S.J. Destination Decision Making and Consumer Demands: Identifying Critical Factors. 2005. Available online: https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/esploro/outputs/report/Destination-decision-making-and-consumer-demands/991012821416002368#file-0 (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Daradkeh, M. Lurkers versus Contributors: An Empirical Investigation of Knowledge Contribution Behavior in Open Innovation Communities. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; So, K.K.F.; Hu, X.; Poomchaisuwan, M. Travel for affection: A stimulus-organism-response model of honeymoon tourism experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 1187–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Yao, J.-Y. What drives impulse buyingX behaviors in a mobile auction? The perspective of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Wang, Y.; Luan, J.; Tang, P. The Influence of physician information on patients’ choice of physician in mHealth services using China’s chunyu doctor app: Eye-tracking and questionnaire study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e15544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Murphy, M.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Dhir, A. What drives brand love and purchase intentions toward the local food distribution system? A study of social media-based REKO (fair consumption) groups. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Bonn, M. Can the value-attitude-behavior model and personality predict international tourists’ biosecurity practice during the pandemic? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M. Research on the impact of public climate policy cognition on low-carbon travel based on SOR theory—Evidence from China. Energy 2022, 261, 125192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.; Kılıçlar, A. The effect of tourists’ gastronomic experience on emotional and cognitive evaluation: An application of SOR paradigm. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Wee, H.; Anuar, F.I.; Aminudin, N. Motivational Facets, Edu-Tourist and Institutional Physiognomies, And Destination Selection Behaviour in An Augmented S-O-R Model: A Conceptual Review. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 2021, 10, 1302–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R.; Surprenant, C.; Czepiel, J.A.; Gutman, E.G. A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surprenant, C.F.; Solomon, M.R. Predictability and personalization in the service encounter. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, C.H. Cultivating the flower of service: New ways of looking at core and supplementary services. In Marketing, Operations and Human Resources Insights into Services; Eigler, P., Langeard, E., Eds.; Institute d’Administration des Enterprises: Aix-en-Provence, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hightower, R., Jr. Commentary on Conceptualizing the Servicescape Construct In ’A Study of The Service Encounter in Eight Countries. Mark. Manag. J. 2010, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Yin, D.; Qiu, H.; Bai, B. A systematic review of AI technology-based service encounters: Implications for hospitality and tourism operations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, S. Managing Employee Attitudes and Behaviors in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry; Nova Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, M.; Chowdhary, N. Internal Destination Development: A Case of Capacity Building in India. In Proceedings of Tourism International Scientific Conference Vrnjačka Banja-TISC; TISC: Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia, 2019; pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, K.; Abbasi, A.Z.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Schultz, C.D.; Ting, D.H.; Ali, F. Local food consumption values and attitude formation: The moderating effect of food neophilia and neophobia. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 464–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yan, L.; Mak, C.K.Y. Service encounter failure, negative destination emotion and behavioral intention: An experimental study of taxi service. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K.; Parsa, H.; Parsa, R.A.; Bujisic, M. Change in consumer patronage and willingness to pay at different levels of service attributes in restaurants: A study in India. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 15, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, A.Y.; Baykal, M.; Koc, E. Attitudes of hotel customers towards the use of service robots in hospitality service encounters. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio, C.; Madera, S.L.R.; Pérez, J. Trans women in tourism: Motivations, constraints and experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Orbell, S. Attitudes, habits, and behavior change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 73, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitsamer, B.F.; Brunner-Sperdin, A.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. Destination attractiveness and destination attachment: The mediating role of tourists’ attitude. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajitmutita, L.M.; Perényi, Á.; Prentice, C. Quality, value?–Insights into medical tourists’ attitudes and behaviors. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajada, T.; Titheridge, H. The attitudes of tourists towards a bus service: Implications for policy from a Maltese case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 4110–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R.; Hughes, K. Chinese and Australian tourists’ attitudes to nature, animals and environmental issues: Implications for the design of nature-based tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. Generational differences in content generation in social media: The roles of the gratifications sought and of narcissism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosuthi, N.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, H. Impact of distance on the arrivals, behaviours and attitudes of international tourists in Hong Kong: A longitudinal approach. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 103963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W. Reading. In The Nature of Attitudes and Attitude Change; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1969; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam, A.; Fleischer, A.; Mansfeld, Y. Tourism and social change: The case of Israeli ecotourists visiting Jordan. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Teye, V.; Paris, C. Innocents abroad: Attitude change toward hosts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.S.; Wang, B. Social contact theory and attitude change through tourism: Researching Chinese visitors to North Korea. Tour Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Green purchase and sustainable consumption: A comparative study between European and non-European tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Cao, X. The effect of tourist-to-tourist interaction on tourists’ behavior: The mediating effects of positive emotions and memorable tourism experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.X.; Zhang, H.Q.; Jenkins, C.L.; Lin, P.M. Does tourist–host social contact reduce perceived cultural distance? J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Sparks, P. Theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour. Predict. Health Behav. 2005, 2, 121–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.H.; Lee, E.-J. Segmentation of senior motorcoach travelers. J. Travel Res. 2002, 40, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. An investigation on customer revisit intention to theme restaurants: The role of servicescape and authentic perception. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1646–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Kim, M.J.; Jo, S.J. The relationships between perceived team psychological safety, transactive memory system, team learning behavior and team performance among individual team members. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 958–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, H. Museums and touristic expectations. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Residual effects of past on later behavior: Habituation and reasoned action perspectives. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 6, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.T.; Ryan, C. Museums, exhibits and visitor satisfaction: A study of the Cham Museum, Danang, Vietnam. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2013, 11, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Kim, J. Does location matter? Exploring the spatial patterns of food safety in a tourism destination. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayih, B.E.; Singh, A. Modeling domestic tourism: Motivations, satisfaction and tourist behavioral intentions. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.; Mohammed, H.J.; Kiumarsi, S.; Kee, D.M.H.; Anarestani, B.B. Destinations food image and food neophobia on behavioral intentions: Culinary tourist behavior in Malaysia. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2023, 35, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.I.; Karl, M.; Wong, I.A.; Law, R. Tourism destination research from 2000 to 2020: A systematic narrative review in conjunction with bibliographic mapping analysis. Tour. Manag. 2023, 95, 104686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutek, B.A.; Bhappu, A.D.; Liao-Troth, M.A.; Cherry, B. Distinguishing between service relationships and encounters. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, B.; Mavondo, F. Tourism destinations: Antecedents to customer satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 833–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, C.H.; Yip, G.S. Developing global strategies for service businesses. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, B.; Ferreira, M.C.; Dias, T.G. Tourism as a service: Enhancing the tourist experience. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Song, H. Does the perception of smart governance enhance commercial investments? Evidence from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Henard, D.H. Customer satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxham III, J.G. Service recovery’s influence on consumer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L.; Packer, J. Minds on the move: New links from psychology to tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 386–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Tuo, S.; Lei, K.; Gao, A. Assessing quality tourism development in China: An analysis based on the degree of mismatch and its influencing factors. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Firdousi, S.F.; Obrenovic, B.; Afzal, A.; Amir, B.; Wu, T. The influence of green finance availability to retailers on purchase intention: A consumer perspective with the moderating role of consciousness. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 71209–71225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seger-Guttmann, T.; Gilboa, S. The role of a safe service environment in tourists’ trust and behaviors–the case of terror threat. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henly, S.J. Robustness of some estimators for the analysis of covariance structures. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1993, 46, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J. Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierar-chical approach. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, R., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Baker, T.L. Investigating the role of the physical environment in hedonic service consumption: An exploratory study of sporting events. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Content | N | Percentage (%) | Cumulative Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 548 | 52.04 | 52.04 |

| Female | 505 | 47.96 | 100 |

| Age | |||

| 18–28 | 233 | 22.13 | 22.13 |

| 29–40 | 343 | 32.57 | 54.70 |

| 41–48 | 286 | 27.16 | 81.86 |

| 49–55 | 105 | 9.97 | 91.83 |

| 56–65 | 67 | 6.36 | 98.19 |

| Above 65 | 19 | 1.8 | 99.99 |

| Personal Monthly Income | |||

| Less than 1000 CNY | 43 | 4.08 | 4.08 |

| 1000–1999 CNY | 85 | 8.07 | 12.15 |

| 2000–4999 CNY | 254 | 24.12 | 36.27 |

| 5000–7999 CNY | 406 | 38.56 | 74.83 |

| 8000–14,999 CNY | 213 | 20.23 | 95.06 |

| More than 15,000 CNY | 52 | 4.94 | 100 |

| Education | |||

| Middle school and below | 81 | 7.69 | 7.69 |

| High school | 201 | 19.09 | 26.78 |

| Undergraduate degree | 673 | 63.91 | 90.69 |

| Master’s/PhD | 98 | 9.31 | 100 |

| Construct | Variable | SL | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SESPs | Service attitude factor | 0.865 | 0.68 | |

| The employees are friendly to me. | 0.849 | |||

| The employees are willing to help me. | 0.818 | |||

| I can see from the employees’ attitudes that they understand my needs. | 0.807 | |||

| Service skill factor | 0.857 | 0.666 | ||

| The employees know their jobs well. | 0.848 | |||

| The employees can answer my questions quickly. | 0.774 | |||

| The employees can use their knowledge to meet my needs. | 0.825 | |||

| Service response factor | 0.865 | 0.681 | ||

| The employees undertake actions to address my needs. | 0.848 | |||

| The employees give quick responses to my needs. | 0.793 | |||

| I can see from the employees’ behavior that they understand my needs | 0.834 | |||

| SESEs | Service atmosphere factor | 0.927 | 0.68 | |

| The enterprises have a pleasant smell. | 0.885 | |||

| The lighting is excellent in the enterprises. | 0.834 | |||

| The enterprises are clean. | 0.823 | |||

| The temperature in the enterprises is pleasant. | 0.831 | |||

| The background music is appropriate. | 0.827 | |||

| The background noise level in the enterprises is acceptable. | 0.742 | |||

| Physical environment factor | 0.942 | 0.619 | ||

| The enterprises have more than enough space for me to be comfortable. | 0.847 | |||

| The physical facilities in the enterprises are comfortable. | 0.796 | |||

| The enterprises’ interior layout is pleasing. | 0.771 | |||

| The signs used (i.e., bathroom, enter, exit, smoking) in enterprises are helpful to me. | 0.787 | |||

| The restrooms are appropriately designed. | 0.783 | |||

| The parking lot has more than enough space. | 0.775 | |||

| The color scheme is attractive. | 0.787 | |||

| The materials used inside the enterprises are pleasing and of high quality | 0.791 | |||

| The architecture is attractive. | 0.765 | |||

| The style of the interior accessories is fashionable | 0.765 | |||

| SEDPs | Destination software service environment factor | 0.902 | 0.606 | |

| The destination is clean. | 0.853 | |||

| The air in the destination is fresh. | 0.739 | |||

| The destination has a pleasant landscape. | 0.755 | |||

| The destination has good public security. | 0.757 | |||

| The urban planning of the destination is reasonable. | 0.767 | |||

| The human landscape is in harmony with the natural landscape. | 0.795 | |||

| Destination hardware service environment factor | 0.928 | 0.616 | ||

| The public facilities (toilets, waste containers, rest facilities, safety facilities) are more than enough. | 0.830 | |||

| The public facilities (transportation, toilets) are comfortable | 0.777 | |||

| The public facilities (toilets, rest facilities) are clean. | 0.766 | |||

| The public facilities (transportation, toilets, safety facilities, tourism public information) are convenient. | 0.801 | |||

| The destination has smooth traffic. | 0.766 | |||

| The public facilities (transportation, trash can) are unique. | 0.778 | |||

| The public facilities (toilets, rest facilities) are not damaged. | 0.778 | |||

| The destination uses informatization and intelligent facilities (application, virtual reality, augmented reality, interactive facilities, etc.). | 0.779 |

| Hypothesized Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Supported | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a Attitude | ← | SESPs | 0.547 | 0.152 | 8.156 | *** | Yes |

| H1b Attitude | ← | SESEs | 0.358 | 0.107 | 5.458 | *** | Yes |

| H1c Attitude | ← | SEDPs | 0.076 | 0.123 | 1.546 | 0.122 | No |

| H2a Revisit intention | ← | SESPs | 0.482 | 0.163 | 7.226 | *** | Yes |

| H2b Revisit intention | ← | SESEs | 0.275 | 0.103 | 4.715 | *** | Yes |

| H2c Revisit intention | ← | SEDPs | 0.268 | 0.152 | 4.716 | *** | Yes |

| H2d Recommendation intention | ← | SESPs | 0.53 | 0.183 | 7.412 | *** | Yes |

| H2e Recommendation intention | ← | SESEs | 0.287 | 0.11 | 4.778 | *** | Yes |

| H2f Recommendation intention | ← | SEDPs | 0.142 | 0.126 | 3.158 | 0.002 ** | Yes |

| H3a Revisit intention | ← | Attitude | 0.281 | 0.058 | 5.243 | *** | yes |

| H3b Recommendation intention | ← | Attitude | 0.267 | 0.061 | 4.882 | *** | yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Wareewanich, T.; Yue, X.-G. How to Promote a Destination’s Sustainable Development? The Influence of Service Encounters on Tourists’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914087

Zhang S, Wareewanich T, Yue X-G. How to Promote a Destination’s Sustainable Development? The Influence of Service Encounters on Tourists’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914087

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shu, Thitinant Wareewanich, and Xiao-Guang Yue. 2023. "How to Promote a Destination’s Sustainable Development? The Influence of Service Encounters on Tourists’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914087

APA StyleZhang, S., Wareewanich, T., & Yue, X.-G. (2023). How to Promote a Destination’s Sustainable Development? The Influence of Service Encounters on Tourists’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sustainability, 15(19), 14087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914087