1. Introduction

Numerous studies in the fields of organizational culture and organizational behavior are aimed at understanding individuals’ work experiences and relationships. In this context, the topic of job satisfaction, one of the attitudes towards work, has been among the most extensively researched areas [

1]. The significance of job satisfaction has been validated by numerous studies that demonstrate its impact on various individual and organizational behaviors such as job performance, absenteeism, burnout, organizational citizenship behavior, productivity, and organizational efficiency [

2].

Job satisfaction is a pivotal determinant of the sustainability of educational organizations, particularly within the context of the teaching professions. An elevated level of job satisfaction amongst educators fosters a range of beneficial outcomes that synergistically contribute to organizational stability and growth. Firstly, heightened job satisfaction engenders a sense of intrinsic motivation, positively influencing teachers’ commitment, engagement, and overall performance [

3,

4,

5]. This, in turn, bolsters instructional quality and student outcomes, as satisfied educators are more likely to invest discretionary effort in innovative pedagogical approaches [

4,

6]. Secondly, favorable job satisfaction cultivates a nurturing work environment characterized by reduced turnover rates [

7] and enhanced teacher retention [

8,

9,

10]. The cumulative effect of this phenomenon is the preservation of institutional knowledge and the mitigation of operational disruptions. Moreover, contented teachers are more prone to participate in professional development initiatives and collaborative endeavors, thereby augmenting the organization’s intellectual capital and adaptability to evolving educational landscapes [

7]. Consequently, a profound comprehension of the intricate interplay between job satisfaction, educator well-being, and organizational sustainability is imperative for the strategic management and enduring success of educational entities.

The job satisfaction of teachers holds significant importance within the purview of related theoretical frameworks, too. The intrinsic linkages between job satisfaction and established theories, such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [

4,

11], Herzberg’s two-factor theory [

12], and Locke’s goal-setting theory [

13], underline its pivotal role in shaping educators’ motivational orientations, professional engagement, and overall well-being [

4,

11,

14,

15]. Job satisfaction, as elucidated by these theories, acts as a catalyst for enhancing teachers’ intrinsic motivation, fostering a sense of achievement, and cultivating a positive work environment. Moreover, the alignment of teachers’ contentment with theories such as Bandura’s self-efficacy theory accentuates the reciprocal relationship between job satisfaction and perceived competence, thereby reinforcing teachers’ belief in their ability to excel [

16,

17,

18]. In essence, a comprehensive understanding of the symbiotic interplay between job satisfaction and pertinent theories underscores its role as a foundational factor in sustaining educators’ motivation, commitment [

19], and efficacy, thus contributing to enhanced educational outcomes [

20] and organizational sustainability [

21,

22].

The pandemic and the subsequent exacerbation of economic conditions have exerted influence on numerous facets within educational institutions [

23,

24]. Among these, it is believed that one pertains to the levels of job satisfaction among teachers. As a result of this hypothesis, there is a perceived need to reexamine the levels of teachers’ job satisfaction. Therefore, the intention is to update research on teachers’ job satisfaction and furnish a resource for policymakers and administrators of institutions employing educators. In this context, this study contributes to the field by determining the levels of teachers’ job satisfaction and the influencing factors in terms of sustainability and quality in education through a Turkish sample.

1.1. Literature Review

The notion of job satisfaction, a subject of academic inquiry, has garnered substantial attention within the domains of management, social psychology, and practical application in contemporary times. In truth, investigations into this phenomenon boast an extensive chronicle within the variegated academic realm. A plethora of definitions pertaining to this construct abound within the vibrant and fiercely competitive academic arenas [

25]. One of the pioneers who coined this definition, Locke [

26], defines job satisfaction as a positive emotional state. The concept of job satisfaction is the term given to the feeling of well-being that an individual experiences regarding the work they are engaged in. It is the pleasure derived from one’s work [

27]. According to Eren [

28], job satisfaction stems from the happiness derived from material gain and the creation of a work, product, or service through one’s efforts. The evolutionary trajectory of job satisfaction’s delineation traverses from a solitary perspective towards a proliferation of multiple perspectives. These are the single perspective (affection) and multiple perspectives (affection and cognition) [

27]. In conclusion, irrespective of the vantage points researchers adopt in their investigation of the job satisfaction concept, their delineations of job satisfaction tend to revolve around personal sentiments. If employees experience affirmative and gratifying emotions in their professional milieu, their dispositions towards their work are classified as indicative of job satisfaction. Conversely, when employees harbor adverse and disagreeable emotions within their occupational context, their orientations towards their work are characterized as dissatisfied, as noted by Yuewei Chen (2005), cited in [

27]. The unequivocal explication of job satisfaction has proven elusive from its definitional construct [

29]. However, in brief definition, job satisfaction can be described as the expression of employees’ emotional and contentment states toward their jobs.

Job satisfaction holds considerable importance in the normal course of life for individuals working within organizations. Expressing our lives solely through the emotions we feel outside of work would not be accurate. On the contrary, our emotional states within our work, where we dedicate a significant portion of our lives to generating income and experiencing spiritual satisfaction, play a significant role. Individuals who find satisfaction in their work tend to lead healthier, happier lives and become successful members of their social circles. If individuals do not derive satisfaction from their jobs, they gradually begin to alienate themselves, first from themselves, then from the organization they work for, and eventually from society at large [

30]. Hence, an increase in individual job satisfaction would lead to an enhancement in both their intrinsic happiness and, foremost, contribute to an increase in overall societal contentment.

In a society, a high level of job satisfaction among employees is a crucial factor that generally contributes to the overall health and happiness of that society [

31]. The correlation between elevated job satisfaction, heightened employee loyalty, and the progressive trajectory of a company is undeniable. Organizations must center their efforts on employee well-being, a factor with the potential to significantly influence employee satisfaction and loyalty, ultimately impacting their performance. Such dedicated attention to employee welfare ensures optimal engagement and contributions from employees, thus augmenting the overall advancement of the company [

32]. Schmailan [

33] similarly investigated the correlation between job satisfaction and performance, substantiating through the literature that contented employees exhibit enhanced performance and substantively contribute to organizational prosperity, while dissatisfied individuals impede progress. Organizations proficient in fostering job satisfaction within their workforce are poised to cultivate a more efficient and productive cadre, prompting contemporary enterprises to proactively endeavor to meet employees’ expectations, thereby exerting an influence on their performance that subsequently reverberates in the success of the organization [

34].

The perception of job satisfaction can be influenced by numerous factors, categorized primarily under three main headings: demographic, psychological, and environmental. Demographic factors include gender, age; psychological factors encompass attitudes, emotions, behaviors, and personality; and environmental factors can be delineated as the nature of the job, work environment, and organizational stakeholders [

35]. The incongruity arising from disparities between an individual’s anticipations, requisites, or principles pertaining to their occupation and the actual outcomes thereof is explicated through the construct of job satisfaction [

36,

37].

The vocation of education, which bears the solemn duty of fostering forthcoming cohorts, stands as an altruistic and labor-intensive pursuit. Within academic establishments, a constructive organizational ambiance significantly bolsters institutional progress. Undertaking the task of cultivating this affirmative milieu within the organization, educational leaders and administrators assume an imperative role. As posited by Subagja and Safrianto (2020, cited in [

32]), individuals who experience job satisfaction are inclined to manifest loyalty towards their employing organization, alongside exhibiting substantial engagement in their work. This predisposition further facilitates their ongoing commitment to enhancing their overall job performance. From this perspective, it can be argued that the more teachers engage in their work with satisfaction and the higher their job satisfaction, the more productive educational processes and outcomes can be expected to emerge. When examining the factors that determine teachers’ job satisfaction, it is evident that leadership attitudes and behaviors, working conditions, and the school environment are the most influential factors on job satisfaction [

38].

Looking at studies conducted in developed countries regarding teachers’ job satisfaction, it has been identified that factors such as a lack of professional autonomy, diminishing resources, insufficient salaries, and constant media criticism are reasons for low levels of job satisfaction among teachers [

39,

40,

41]. Based on the findings of numerous research endeavors, it has been observed that individual characteristics such as gender, age, marital status, parenthood, and experience also influence job satisfaction [

42]. Factors that contribute to a decrease in teacher job satisfaction include heavy workloads, administrative tasks, low pay, administrative personnel and routines, student behavior and discipline-related issues, peer environment, inadequate professional development opportunities, and diminishing respect for the teaching profession [

43].

1.2. Teachers Working Conditions: The Turkish Sample

In Turkey, teachers work under the auspices of the Ministry of National Education. Teacher employment is observed within the public sector as well as in private schools. Teachers may assume roles across different tiers (primary school, middle school, high school) and various subject areas (science, social studies, literature, mathematics, etc.). Typically, teachers conduct their lessons during school hours. During non-teaching hours, they engage in tasks such as classroom preparation, student monitoring, parent meetings, and similar duties. The working hours of teachers may vary based on the type of school and student density. Remuneration for teachers varies based on their titles, seniority, and placement locations. Teachers employed in the public sector avail themselves of periodic salary increments and benefits related to occupational rights. Among the social benefits are health insurance, retirement plans, and annual leave. Teachers are enabled to sustain their education within their respective fields and foster their professional development. Through seminars, workshops, and educational programs, teachers’ professional skills are updated and enhanced.

Research inquiries into job satisfaction frequently encompass teacher-specific personal attributes such as age and gender, alongside their professional characteristics like years of pedagogical experience, educational attainment, involvement in professional development initiatives, and motivational beliefs [

15]. Accordingly, within the framework of this study, a comprehensive assessment of teachers’ job satisfaction levels was conducted by considering both their personal and professional attributes.

1.3. The Aim of the Research

The objective of this study is grounded in the question, “What are Teachers’ Perceptions of Job Satisfaction?” In addition to determining the levels of job satisfaction among teachers, the aim is also to identify the factors influencing their levels of job satisfaction. In line with this general objective, the following sub-questions were addressed:

In the quantitative dimension of the study, the following questions were explored:

Is there a gender-based difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels?

Is there an age-related difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels?

Is there a marital status-related difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels?

Is there a difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels based on the type of school they work at?

Is there a difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels based on the educational level of the schools they teach at?

Is there a difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels based on their years of service in the institution?

Is there a difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels based on their professional experience?

Is there a difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels based on their graduation status?

Is there a difference in teachers’ job satisfaction levels based on their position on the teacher career ladder?

In the qualitative dimension of the research, the following sub-questions were addressed to determine teachers’ perspectives on job satisfaction:

What are teachers’ levels of job satisfaction?

What factors influence teachers’ levels of job satisfaction?

What enhances teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction?

2. Materials and Methods

A study that incorporates both quantitative and qualitative data and treats these data as significant components is classified as a “mixed” method by Hayveart et al. [

44]. A mixed method involves at least one quantitative and one qualitative method and is not directly aligned with any specific research paradigm. In this study, while seeking numerical data about teachers’ job satisfaction, the aim was also to understand teachers’ perceptions of the concept of job satisfaction and identify the factors that most influence their job satisfaction. In this context, a convergent parallel design was preferred in this study among the types of mixed methods. In a convergent parallel design, quantitative and qualitative data are collected at the same time in online platform, but their analyses are conducted separately. The congruence of the findings obtained from these analyses is then examined to determine whether they corroborate each other. The qualitative data reflecting participants’ perspectives should align with the findings from the quantitative data. Quantitative and qualitative methods hold equal priority; during interpretation and analysis, the results are merged to provide a comprehensive understanding [

45,

46]. Similarly, in this study, quantitative data about teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction were collected using the Job Satisfaction Scale, while open-ended questions designed to elicit teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction were simultaneously collected from participants. These separate findings and results were analyzed and then integrated. In this context, based on the aims of the mixed method, a complementary mixed method was chosen for this study. Complementarity is the guiding principle in a complementary mixed method study, where quantitative and qualitative methods are employed to identify complementary yet distinct facets of a phenomenon.

In this study, a mixed method approach was employed, utilizing both quantitative and qualitative methods, to determine teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction.

Quantitative Dimension: The quantitative dimension of this study employed a survey model, utilizing a scale technique for data collection. The data collection instrument consisted of a scale that was administered to 189 teachers from various subject areas and levels working in public and private schools in the Muş province and its surrounding regions, comprising the accessible population in 2022–2023 academic year. The “Job Satisfaction Scale,” developed by Şahin [

21], was employed, consisting of a total of 42 questions. The validity and reliability assessment of the scale was conducted by Şahin [

21,

47]. The scale consists of 42 questions and encompasses six subscales. The calculated Cronbach’s Alpha value for the scale was found to be 0.91. In terms of subscales, the intrinsic aspect of the job had a value of 0.75, management 0.89, salary 0.81, achievement, respect, and recognition (ARR) 0.78, interpersonal relationships (IR) 0.74, and parent–student neglect (PSN) 0.74. The scale was arranged on a three-point scale of “Yes”, “Partially”, and “No”. Scoring was assigned as follows: “Yes” as “3”, “Partially” as “2”, and “No” as “1”; the reverse was applied for negatively phrased questions. Due to the scale’s three options and two intervals, the range value was determined by dividing the number of intervals in the scale by the number of options, resulting in an interval value of 0.66. Adding one (1) to this value, the range was classified as “dissatisfied” for 1–1.66, “partially satisfied” for 1.67–2.33, and “satisfied” for 2.34–3.00.

Qualitative Dimension: In the qualitative dimension of this study, open-ended questions were preferred as qualitative research methods. Expert opinions (f = 2) were utilized in forming these questions, and a pilot application (f = 6) was conducted to assess question appropriateness. The questions were refined based on participants’ feedback to arrive at the final version. The qualitative questions were also added to the survey form and both of the survey and qualitative questions were sent to the participants online. Within qualitative dimension the participants are asked to respond to the following questions:

What does the concept of “job satisfaction” mean to you? How would you explain it?

What influences your job satisfaction the most? Please explain briefly.

What factors contribute to increasing your job satisfaction? Please explain briefly.

Open-ended questions were crafted to gather qualitative research data. The interview questions were formulated through a review of the literature and in alignment with the research objectives. To assess the appropriateness of the research questions, opinions were sought from two experts in the field of educational administration. To test the clarity of the questions thus formulated, a small group of teachers (f = 5) participated in a pilot application. Based on feedback, the final version of the form containing open-ended questions for the research was prepared. Lastly, the questionnaire items and open-ended questions for the quantitative dimension of the study were transferred to Google Forms. The implemented form consists of three sections: the first section includes demographic information, the second section contains the job satisfaction scale, and the third section encompasses the open-ended questions. The online application of the form was conducted among teachers from various subject areas and levels working in public and private schools in various cities across Turkey. In determining the research sample, simple random sampling and maximum diversity sampling methods were employed. Simple random sampling ensures equal probability of selection for each sampled element, ensuring that the selected elements are included in the sample. All units in the population have an equal and independent chance. Maximum diversity sampling involves identifying similar but distinct situations related to the problem under investigation within the population and conducting the research accordingly [

48].

3. Results

In the research, the data obtained through the application of the scale were analyzed using the SPSS 25.0 statistical software package. Before conducting fundamental statistical analyses on the obtained data, the reliability coefficient for the entire scale was calculated, resulting in a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.91. Subsequently, the normality of data distribution and the homogeneity of variances were examined. The skewness and kurtosis coefficients were determined as 0.28 and −0.49, respectively. Accordingly, for independent two-sample groups showing normal distribution, an independent samples t-test was applied to determine the differences between means, while a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized for determining differences among more than two groups.

In the study, the “job satisfaction” phenomenon of teachers serving in all subject areas and levels was explored by defining how they perceive it. This study aimed to identify the factors influencing teachers’ job satisfaction, ascertain the key elements contributing to increased job satisfaction, and evaluate these factors. To achieve these objectives, the Job Satisfaction Scale was employed along with a multiple-choice survey question added to determine which factor most affects job satisfaction. The scale questions in the quantitative dimension were supplemented with three open-ended questions. Among the 189 teachers, four provided invalid responses, which were excluded from the analysis. The teacher opinions were numbered as T1 (Teacher, First Rate), T2, and T3, and the citations were presented with these numberings.

The frequency distributions based on gender, age, marital status, school type, school level, years of service at the current institution, professional experience, graduation status, and positions within the teacher career hierarchy for the cohort of 189 participants in the research are delineated across

Table 1 and

Table 2. An analysis of the demographic outcomes reveals that among the research participants, 119 individuals were female, while 70 individuals were male. Predominantly, a considerable portion of the participants are situated within the age bracket of 21–30 years (n = 89). Within the age range of 31–40, the participation count is 64, whereas 29 individuals were in the age range of 41–50. It is evident that participation extends to individuals aged 51 and above. Marital status data indicate that a significant majority of participants are married (n = 101). Furthermore, a substantial proportion of the participants are affiliated with public educational institutions (n = 150), while 39 participants are associated with private schools. In terms of scholastic strata allocation, a prevalent number of educators operate within the primary school level (n = 78), followed by 59 educators at the middle school level and 40 educators at the high school level. However, the preschool level demonstrates the least representation (n = 12) amongst the participants. Assessing the duration of service among educators within their respective institutions, it is discernible that the highest number of educators (n = 122) accrued service spanning 0–3 years. Conversely, the lower end of the representation spectrum pertains to educators with a tenure of 7–9 years (n = 12) within the same institution. Reviewing the distribution concerning educators’ educational attainments, a predominant majority attained bachelor’s degrees (n = 157). Additionally, 29 educators hold master’s degrees, and 3 educators possess Ph.D. degrees. Delving into educators’ professional experience, it becomes evident that a substantial portion (n = 84) possesses experience ranging from 0 to 5 years. Among the participants, 48 educators possess 6–10 years of experience, followed by 22 educators with 11–15 years of experience, and 18 educators with 21 years or more of experience. The least representation is associated with educators holding 16–20 years of experience. Surveying the distribution contingent upon educators’ positions within the career hierarchy, the largest subset comprises educators (n = 129) who do not hold designations as specialist teachers or head teachers. The research encompasses 56 specialist teachers and 4 head teachers.

As a result of the conducted analysis, the average score of teachers’ job satisfactions was determined as 1.85. According to the three-level rating, based on the Teacher Job Satisfaction Scale evaluated by Şahin [

47], it was observed that the job satisfaction levels of teachers are at a moderate level.

When examining

Table 1, it becomes apparent that the perceptions regarding teachers’ job satisfaction do not reveal a statistically significant distinction linked to their genders (

p = 0.09). Despite this, it is worth noting that the job satisfaction levels of female teachers (mean = 1.88) appear marginally higher in comparison to their male counterparts (mean = 1.80); however, this variance lacks statistical significance (

p > 0.05).

Upon analyzing the data presented in

Table 1, a

t-test was employed to assess the distribution of job satisfaction scores among teachers based on their respective school types (

p > 0.05). The outcomes of this test reveal no statistically significant discrepancy in the job satisfaction levels among teachers’ contingent upon the types of schools they are affiliated with. However, divergent results emerge when considering school levels (

p = 0.01). In this context, teachers employed in private schools exhibit elevated job satisfaction scores (mean = 1.97) when juxtaposed with their counterparts in public schools (mean = 1.97). Consequently, the dichotomy between public and private school environments emerges as a pivotal determinant impacting teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction. This observation aligns with the conclusions drawn in the study by Taşdan and Tiryaki [

49], titled “Comparison of Job Satisfaction Levels of Teachers in Private and State Primary Schools,” wherein higher job satisfaction scores were reported among teachers affiliated with private primary schools in contrast to their counterparts in state schools.

In the context of scrutinizing

Table 1, the distribution of teachers’ job satisfaction levels concerning their marital status was assessed utilizing

t-test analysis results (

p > 0.05). The outcomes suggest the absence of any statistically significant variance in teachers’ job satisfaction levels attributed to marital status (

p = 0.50). It is notable, however, that married teachers demonstrate marginally elevated mean job satisfaction scores (mean = 1.87) compared to their unmarried counterparts (mean = 1.85), although this distinction lacks statistical significance.

Turning to

Table 1, a

t-test was executed to explore potential variations in teachers’ job satisfaction scores corresponding to their educational attainment (

p > 0.05). The findings of this test underscore a noteworthy divergence between teachers’ job satisfaction levels and their educational backgrounds (

p = 0.017). This delineates that educators possessing master’s or doctoral degrees (mean = 1.99) manifest heightened levels of job satisfaction in comparison to those with solely bachelor’s degrees (mean = 1.83).

An examination was conducted using ANOVA tests to assess the distribution of teachers’ job satisfaction levels across various factors. Firstly, the age variable of teachers was investigated and the ANOVA test results for job satisfaction scores based on the age variable of teachers do not indicate a significant difference (p = 0.83), (p > 0.05). Secondly, the distribution based on the school levels where teachers are employed was investigated (p > 0.05). The analysis of the results revealed that there is no significant difference in teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction across different school levels (p = 0.082). Subsequently, another ANOVA test was performed to explore the impact of the duration of teachers’ employment in the institution on their job satisfaction scores (p > 0.05). The findings indicate that the length of employment does not yield a substantial alteration in teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction (p = 0.412). Moreover, the distribution of job satisfaction scores in relation to the professional experience of teachers was analyzed using another ANOVA test (p > 0.05). The outcomes indicate that the level of professional experience does not lead to a noteworthy shift in teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction (p = 0.925). Lastly, the distribution of job satisfaction scores was assessed based on teachers’ career positions within the teacher career ladder through another ANOVA test (p > 0.05). The results suggest that different career positions within the ladder do not significantly influence teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction (p = 0.576).

From

Table 2, it can be concluded that the distribution of teachers’ job satisfaction levels based on various factors does not yield statistically significant differences. The application of ANOVA tests across different variables, including age, school levels, duration of employment in the institution, professional experience, and career positions within the teacher career ladder, resulted in

p-values greater than 0.05 in all cases. This suggests that these factors do not significantly influence teachers’ perceptions of job satisfaction. In other words, this study indicates that differences in school levels, duration of employment, professional experience, and career positions within the teaching hierarchy do not lead to notable variations in how teachers perceive their job satisfaction.

The qualitative findings are as follows:

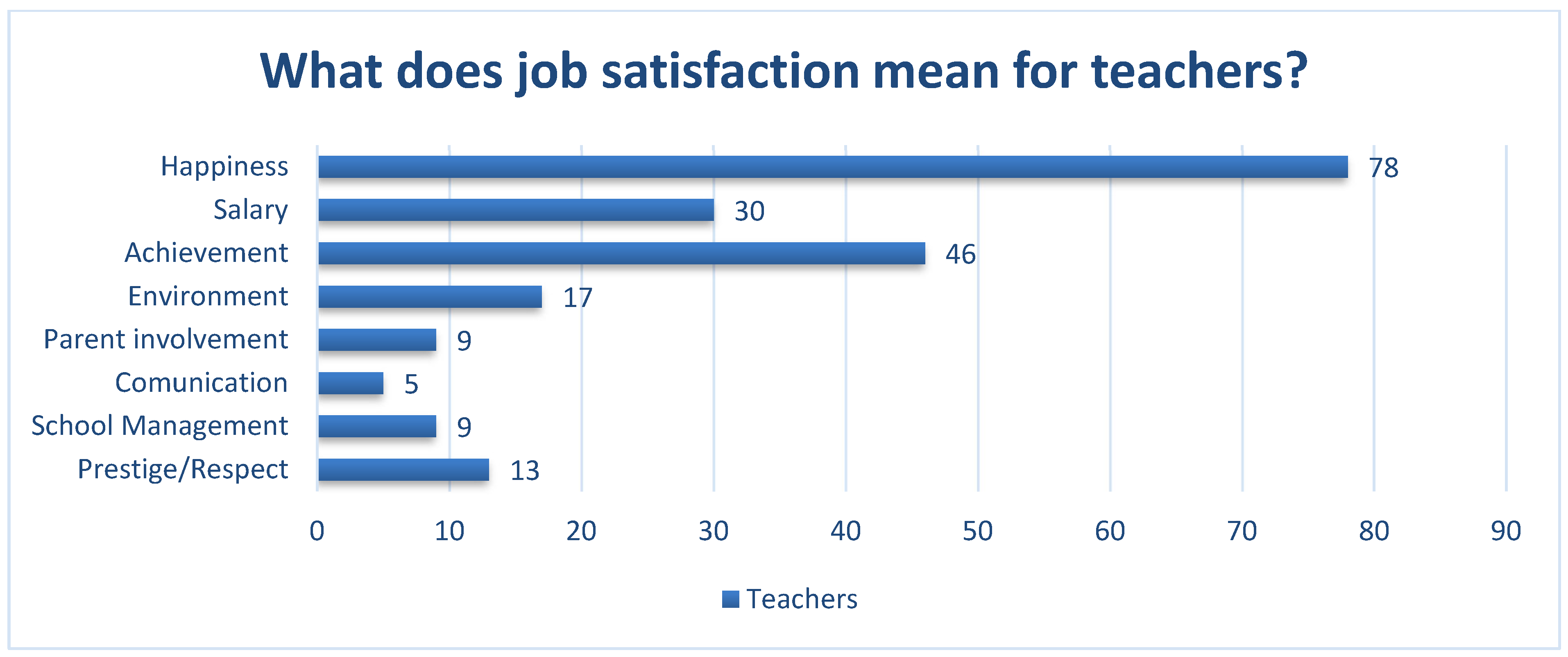

When examining

Figure 1, teachers’ perspectives on the definition of job satisfaction are categorized into eight sub-dimensions: happiness (f = 78), achievement (f = 46), salary (f = 30), environment (f = 17), respect (f = 13), school management (f = 9), parent involvement (f = 9), and communication (f = 5). Some noteworthy expressions are as follows:

(T36): “Job satisfaction is when a person feels happy and secure while doing their work”.

(T75): “Job satisfaction is feeling happy at the end of the day”.

(T180): “Job satisfaction means being able to leave a mark in the lives of my students and their parents. It means being a guide for them to become useful members of society and humanity, constantly questioning, researching, renewing oneself under the light of science, and contributing to their ability to be individuals attached to national and spiritual values”.

(T14): “Job satisfaction is being able to work in a fair and productive environment with sufficient respect in all aspects within society, along with a decent salary”.

From these sentences, it can be concluded that job satisfaction is a multifaceted concept encompassing feelings of happiness, security, and contentment derived from one’s work. It involves a sense of fulfillment achieved through contributing positively to the lives of others, especially in an educational context. Job satisfaction is tied to personal growth, continuous learning, and a sense of purpose, while also encompassing factors like a fair and productive work environment, respect, and appropriate remuneration within society.

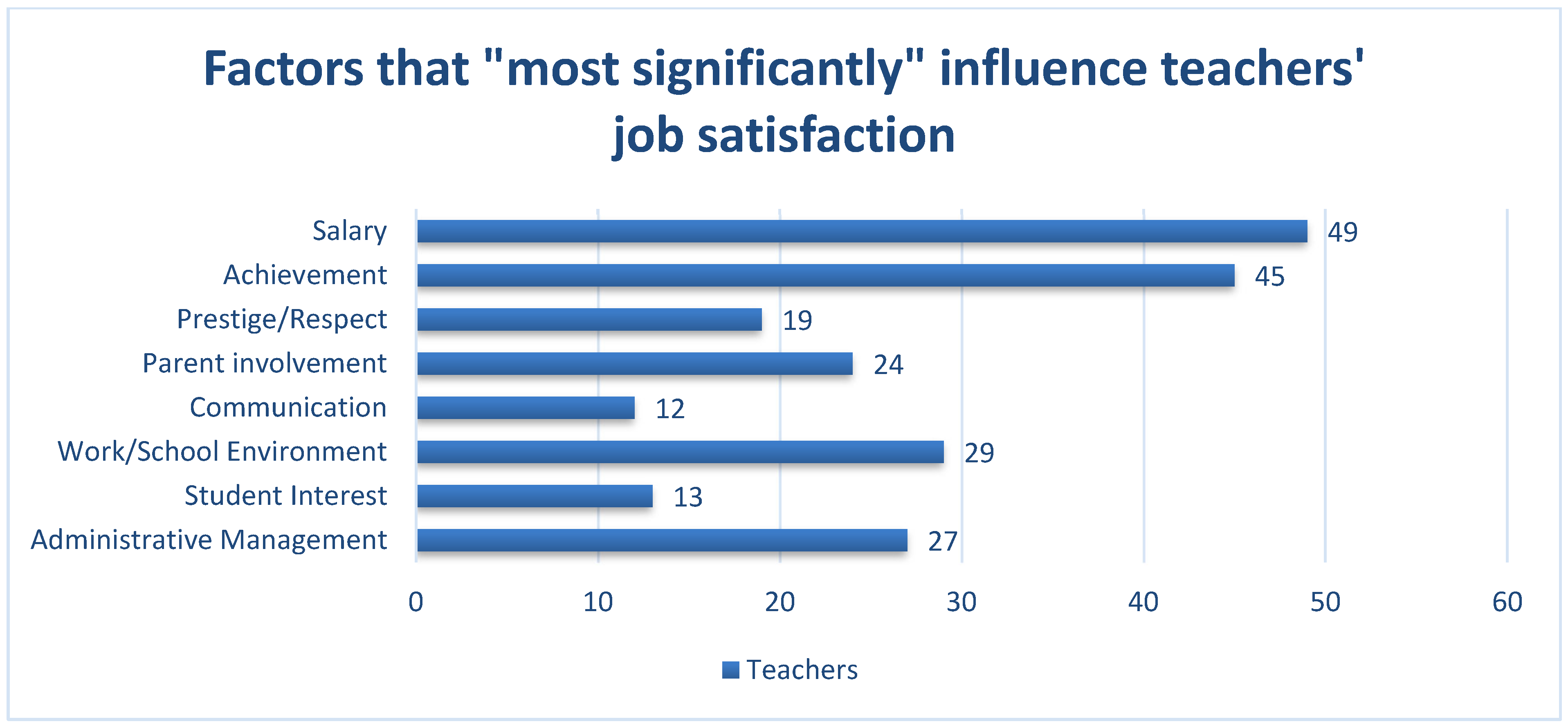

Upon examining

Figure 2, the factors most affecting teachers’ job satisfaction levels can be categorized into eight sub-dimensions: salary (f = 49), achievement (f = 45), environment (f = 29), administrative management (f = 27), parent involvement (f = 24), prestige/respect (f = 19), student interest (f = 13), and communication (f = 12). Accordingly, teachers’ job satisfaction is most influenced by the aspect of salary. Teachers have expressed that in this dimension, receiving a high and fair salary, having a good budget, and feeling financially secure are the factors that most significantly affect their job satisfaction. Some example expressions are as follows:

(T24): “I consider the facilities of the school I work at, my relationships with the people I work with, and the ability of the salary I receive to provide me with a moderate level of financial standard of living”.

(T62): “Receiving the salary I deserve positively affects my job satisfaction”.

(T182): “Respect and financial well-being, because if a teacher cannot receive the necessary respect from the environment and cannot achieve financial sufficiency, their performance displayed will decrease to the same extent”.

From

Figure 2 and the statements, it can be inferred that various factors contribute to job satisfaction among teachers. These factors encompass the quality of the workplace facilities, interactions with colleagues, and financial remuneration that supports a moderate standard of living. The adequacy of salary is emphasized as a positive influence on job satisfaction, underlining the significance of financial compensation. Moreover, the presence of respect and financial stability is highlighted as crucial for maintaining a teacher’s performance and job satisfaction. If teachers are unable to garner respect from their environment or attain financial security, their effectiveness and satisfaction with their role are likely to diminish accordingly.

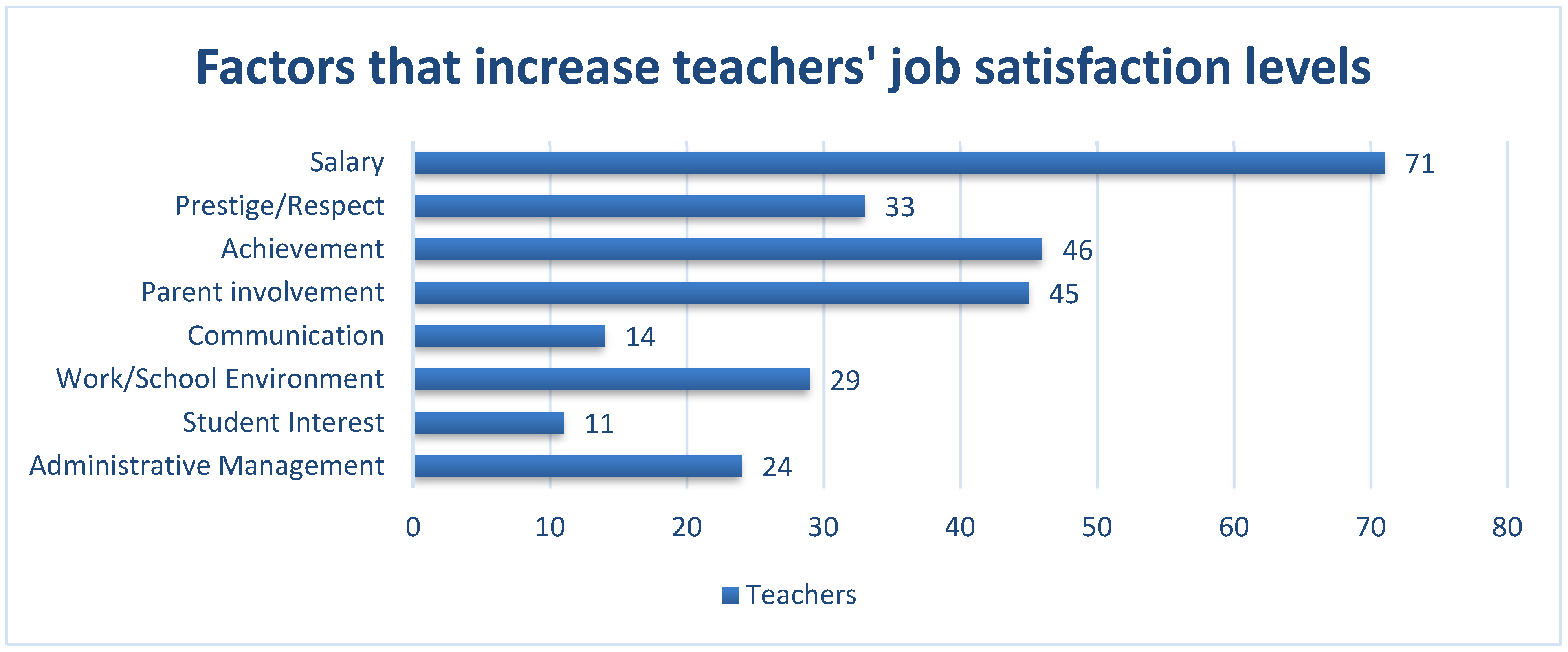

When examining

Figure 3, based on the answers given to the question about factors that increase teachers’ job satisfaction levels, the sub-dimension of salary (f = 71) received the highest number of responses. Achievement (f = 46) and parent involvement (f = 45) follow the salary sub-dimension. In this context, while teachers’ job satisfaction is mostly influenced by salary, it can be stated that the most significant factor that increases teachers’ job satisfaction is the salary aspect. Teachers have expressed that student achievement, a harmonious school environment, and a good salary are factors that contribute to increasing their job satisfaction. Some of the quotations are as follows:

(T22): “A fair salary, a good school culture, parent support, and students’ willingness to learn are very important to me. Particularly, the students’ desire to learn enhances my motivation. It provides me with the opportunity to improve myself”.

(T73): “The students’ approach to the class and their enthusiasm are motivating factors. Healthy communication between teachers and administration provides a comfortable working environment. Knowing that I am financially rewarded for my effort also positively affects my job satisfaction”.

(T103): “A positive school atmosphere, open-minded administration for innovations, sufficient parent support, good salary, curious and engaged students who are open to education, and also the school’s financial resources are factors that I believe have an effective impact”.

From

Figure 3 and the statements, it can be deduced that several interconnected elements play a pivotal role in influencing job satisfaction among educators. These factors include a fair salary, a conducive school culture, supportive parents, and students’ eagerness to learn. The motivation of teachers is heightened by students’ enthusiasm for learning, fostering a space for personal growth. Additionally, the positive dynamics between students’ engagement in the classroom, effective communication with the administration, and financial rewards for effort contribute to a satisfying work environment. An environment characterized by a positive school atmosphere, an administration receptive to innovation, ample parental support, a competitive salary, and resourceful financial backing are collectively deemed instrumental in enhancing job satisfaction among teachers.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The current study used a mixed methods approach to examine the job satisfaction of teachers in Turkey. Two aims characterize the current study. The first aim was to explore which demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, marital status, experience, career stage, academic qualifications) are associated with job satisfaction. The second aim was to determine the factors that affect job satisfaction levels of teachers and was to reveal the perceptions of teachers towards job satisfaction.

In this study aimed at determining perceptions of teachers’ job satisfaction and identifying influencing factors, it was found that teachers’ job satisfaction levels are at a “moderate” level (mean = 1.85). The reason for teachers’ job satisfaction levels being at this level is thought to stem from their inadequate feelings of respect, achievement, recognition, and salary aspects within their profession, as indicated by the qualitative findings. While a significant majority of teachers defined the concept of “job satisfaction” as deriving pleasure and a sense of happiness from their work, they expressed that their job satisfaction is mostly influenced by the achievement and salary sub-dimensions.

Examining the variables influencing teachers’ job satisfaction, it was determined that there is no significant difference in teachers’ job satisfaction scores based on gender (

p = 0.09). While the gender of female or male teachers does not exhibit a significant difference in their job satisfaction, it is observed that female teachers have higher job satisfaction levels (mean = 1.88) than male teachers’ job satisfaction levels (mean = 1.80). Similar outcomes have also been obtained in a study related to job satisfaction. It is observed that gender does not have a significant impact on job satisfaction [

50]. However, in some studies, male educators frequently exhibit higher levels of satisfaction in comparison to their female counterparts [

51,

52]. However, in another study, it was observed that job satisfaction levels of female teachers are higher [

53]. Therefore, making a definitive generalization on this matter does not seem possible.

There is no significant difference between teachers’ job satisfaction scores and their marital status (

p = 0.50). However, it has been found that married teachers’ job satisfaction mean scores (mean = 1.87) are higher than unmarried teachers’ job satisfaction means scores (mean = 1.85). Although this research does not reveal a significant difference, it is observed that married teachers tend to have higher levels of job satisfaction compared to unmarried teachers. Previous studies have also demonstrated that individuals who are married tend to be happier in their jobs and have higher levels of job satisfaction compared to those who are single or divorced [

54,

55].

The type of school where teachers work has a significant difference on their job satisfaction (

p = 0.01). Accordingly, teachers working in private schools have higher job satisfaction scores (mean = 1.97) compared to teachers working in public schools (mean = 1.97). It can be observed that teachers working in private schools have higher job satisfaction than those working in public schools. This result is supported by the findings of Taşdan and Tiryaki [

49], whose study titled “Comparison of Job Satisfaction Levels of Teachers in Private and State Primary Schools” indicated that teachers in private primary schools had higher job satisfaction scores than those in state schools. In a similar vein, one study indicated a significant difference in job satisfaction between teachers in government and private schools. In terms of mean scores, the study found that teachers in private schools exhibited higher levels of job satisfaction compared to their counterparts in government schools [

56]. On the other hand, Bhat [

57] did not identify a disparity in terms of job satisfaction between private and public schools. The unexpectedness of private schools either yielding higher levels of job satisfaction or displaying no discernible difference in job satisfaction levels is quite intriguing. Within the context of Turkey, considering compensation and job security, it could be anticipated that job satisfaction would be lower in private schools; however, the increased satisfaction among teachers in private schools could be attributed to the work environment. Indeed, the literature has underscored the significant role of the work environment in influencing job satisfaction [

15]. Furthermore, studies have indicated that job satisfaction may be more aligned with an individual’s emotional connection to their profession rather than being contingent on whether the institution is private or public, thereby suggesting that the type of school might not be a decisive factor [

58].

There is a significant difference in teachers’ job satisfaction scores based on their educational background variable (

p = 0.017). Therefore, teachers with master’s and doctoral degrees (mean = 1.99) have higher job satisfaction than teachers with only bachelor’s degrees (mean = 1.83). Similarly, this situation is supported by recent studies. In this regard, Pérez Fuentes et al. [

59] demonstrated in their study that teachers graduating with a master’s degree in education scored significant levels of job satisfaction, ranging between high and moderate. This finding, akin to those of other research [

54,

59,

60], confirms that job satisfaction is maintained or generated with increased qualifications and teacher preparation opportunities. On the other hand, this finding contradicts the results of the studies by Koruklu et al. [

61] and Gençtürk and Memiş [

62]. Based on these studies, no statistically significant correlation was identified between the educational institution from which teachers graduated and their level of job satisfaction. As indicated by this study, individuals with master’s and doctoral degrees tend to exhibit higher levels of job satisfaction. Therefore, it can be inferred that school organizations supporting the professional development of teachers would not only contribute to their job satisfaction but also indirectly enhance student achievement [

63] and organizational efficiency. In line with this, Bernarto et al. [

64] demonstrated in their research that perceived organizational support influences job satisfaction.

It was determined that the position of teachers within the career ladder does not show a significant change in their perceptions of job satisfaction (

p = 0.576). Teacher career positions, as outlined in the “Regulation on Candidate Teaching and Teacher Career Stages” prepared based on the Teacher Profession Law (Law No. 7354) dated 3 February 2022, by the Ministry of National Education, involve three distinct stages: teacher, specialist teacher, and head teacher, after the teacher candidate period (Ministry of National Education, 2022 [

65]). Given the recent implementation of these career ladder stages, it can be argued that these stages have not yet caused any significant changes in teachers’ job satisfaction due to their relatively recent implementation. Due to the newly implemented nature of the teacher career ladder system and the lack of sufficient time for it to have a significant impact on teachers’ job satisfaction, it is believed that a meaningful difference has not yet emerged. Gümüşeli [

66] states that the primary purpose of the teacher career ladder system is to enhance teacher qualifications and contribute to teachers’ professional development. If these benefits are achieved, it is anticipated that teachers’ job satisfaction could also increase. In the same study, Gümüşeli [

66] criticized the teacher career ladder system for having little significance beyond providing a partial salary increase and for being in violation of the principle of equal pay for equal work, emphasizing that this situation might not sufficiently motivate teachers. This situation could potentially have a negative impact on teachers’ job satisfaction. In their study titled “Teacher Perspectives on Teacher Career Ladder Systems” Özdemir et al. [

67], expressed that teachers find it inaccurate for teacher career ladder systems to be based solely on seniority and to be evaluated only in terms of salary increases.

In accordance with the findings derived from the qualitative research phase, it is noteworthy that teachers predominantly define job satisfaction as “happiness.” Consequently, it can be inferred that teachers experience job satisfaction when they are content with their work, expressing happiness in their roles. In a similar vein, Aziri [

68] established a connection between job satisfaction and the degree of contentment an individual experiences with their occupation, particularly with respect to intrinsic motivational factors.

In response to an open-ended question that investigated what factors enhance teachers’ job satisfaction, the highest number of responses (f = 71) indicated “salary”. Consequently, teachers predominantly expressed that receiving a high and fair salary enhances their job satisfaction. In the study by Şahin and Dursun [

69,

70], it was concluded that teachers were “dissatisfied” with the “salary” sub-dimension of job satisfaction. In this context, it can be stated that teachers may not feel financially sufficient and may experience economic difficulties. Teachers aspire to practice their profession without worrying about their wallets. Like all other professions valued in society, they express the desire to have a salary that reflects the value of their efforts. Similar findings were also evident in the study conducted by Taiwo et al. [

5]. Accordingly, the job satisfaction levels of lower-paid teachers were observed to be lower compared to others. According to the study conducted by Gafa and Dikmenli [

71], primary school teachers have a moderate level of external satisfaction. Considering that external satisfaction includes factors such as inadequate compensation, issues between administrators and teachers, and the physical conditions of the school, these results are in line with the findings of the present study. On the other hand, Clark [

72] asserts in his study that compensation is not a determining factor in job satisfaction. The quality of work, including factors such as working hours, the promise of career advancement, the sense of being beneficial and successful, and interpersonal relationships, combined with compensation, can collectively influence job satisfaction.

In conclusion, it is evident that teachers’ educational background and the type of school they work at have an impact on teachers’ levels of job satisfaction, while variables such as age, gender, marital status, and work experience do not significantly differ. Additionally, qualitative findings indicate that job satisfaction is associated with happiness, with remuneration being a primary determinant. Despite Herzberg’s two-factor theory suggesting that remuneration is not a motivational factor, the absence of inadequacy of remuneration does affect individuals’ motivation [

12]. This circumstance could pose challenges for organizational sustainability. Hence, in cases where compensation or material rewards are deemed insufficient for teachers, a decrease in job satisfaction is apparent. Consequently, considering the effective role of job satisfaction in enhancing teachers’ performance, commitment to the organization, and overall achievements, it is imperative to implement measures that enhance job satisfaction for the sake of organizational sustainability. Therefore, given that numerous studies in the literature underscore the increased efforts and accomplishments of teachers with higher job satisfaction and performance, school organizations may consider advancing and providing opportunities for educational progress and development in teacher training and working policies. This entails fostering a supportive attitude towards teachers, facilitating their willingness to engage in such development, and proposing a remuneration system that facilitates their commitment.