1. Introduction

Organizations have come to recognize the importance of their human capital, particularly their top-performing employees, in sustaining their businesses in today’s competitive 21st-century landscape. Research by Aguinis and O’Boyle [

1] indicates that the top ten percent of employees may generate 30 percent of an organization’s value, with the top quarter of employees creating 50 percent of the value. Standardized human resource management (HRM) is no longer adequate to meet the needs of attracting, motivating, and retaining talented employees [

2]. To reward these few talented employees, organizations incorporate their personal preferences into job design by offering them preferential treatment in the form of idiosyncratic deals (i-deals). These i-deals may include higher salaries, better opportunities for advancement, higher social status, and other resources [

3], as well as preferential selection for new projects, advanced training programs, and serving key high-quality customers [

4].

I-deals, which refer to “voluntary, personalized agreements of a nonstandard nature that are negotiated between individual employees and their employers regarding terms that benefit each party” [

5,

6], have been studied primarily from the perspective of the recipient [

7]. Studies have found that i-deals promote positive cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and performance outcomes for i-dealers, such as self-efficacy [

8], affective commitment [

9], job satisfaction [

10], work engagement [

11], organizational citizenship behavior [

12], voice behavior [

13], and job performance [

14]. However, the implementation of i-deals involves not only a binary interaction between the recipient (target employee) and the grantor (manager) but also a third party, the bystander (coworkers) [

15]. While much progress has been made in understanding the effectiveness of policy management of i-deals from the recipient’s perspective, a comprehensive understanding is limited without the bystander’s viewpoint [

7]. I-deals can only be accessed by a select few talented employees, while the majority of workers remain bystanders. Consequently, the reaction of bystanders to i-deals will be a critical factor in determining the success of differentiated management practices [

5,

6,

16]. I-deals can effectively improve the performance of recipients, but this is not enough to demonstrate the effectiveness of special talent policies. We should also measure the perspective of bystanders; in particular, we need to consider the functional and dysfunctional impacts of individual agreements on those observing the situation [

17]. In other words, i-deals can serve as a positive example and encourage coworkers to improve their performance through positive interpersonal interaction. I-dealers should also strive to gain the understanding and support of their colleagues to avoid any misunderstandings or exclusions that could lead to a decrease in their own performance.

Specifically, we need to understand how i-deals affect coworkers’ functional and dysfunctional outcomes from an interpersonal behavior perspective. On the one hand, feedback seeking is a proactive behavior to acquire valuable information and feedback in the organization [

18,

19,

20], which involves both direct inquiry and indirect monitoring strategies that can effectively promote individual performance [

21]. Considering that i-deals can effectively boost colleagues’ self-improvement motivation [

22] and learning cognition [

23], employees will exploit the opportunity to obtain insightful suggestions to improve performance by observing and imitating the working practices of i-dealers and asking for advice from i-dealers. Therefore, we aim to elucidate the potential of i-deals to improve coworkers’ performance by characterizing positive interactive behavior as feedback seeking.

On the other hand, the literature largely focuses on the negative effects of i-deals on in-role bystander behaviors, such as work withdrawal behavior [

24], turnover [

25], and deviant behavior [

26]. However, the destructive consequences of individual agreements are not limited to colleagues and can also extend to negative interpersonal interactions (e.g., negative workplace gossip), resulting in a lose-lose situation for both the recipient and the bystander. Negative workplace gossip can damage the gossip target’s reputation and image [

27], increase physical and psychological stress [

28], and reduce task performance [

29]. In severe cases, it may even lead to the resignation of talented employees, thus undermining talent management policies. To further understand the dysfunctional effects of i-deals that lead to misunderstandings and confrontations among coworkers, we use negative workplace gossip to characterize the negative interpersonal interactions that result from them.

As the saying goes, “tall trees catch much wind”. Thus, coworkers may regard i-dealers as social references and may use them as a comparison to re-evaluate their own status in the organization [

30]. The result of a comparison of disadvantaged status can lead to the development of workplace envy among coworkers [

31]. Envy is a negative affective state resulting from an upward comparison between the envier and the envied person with respect to the object of envy [

32,

33]. This comparison can manifest in either negative, threatening, or consumptive forms (such as malicious envy) or positive, competitive, and assimilative forms (such as benign envy) [

4]. Malicious envy may lead to cold violence in the workplace [

4,

22,

34,

35,

36], while benign envy can motivate employees to strive to improve themselves [

22,

36]. Specifically, coworkers’ perceptions of other employees’ i-deals (CPOEID) can have a significant impact on how coworkers feel and behave in the workplace [

37,

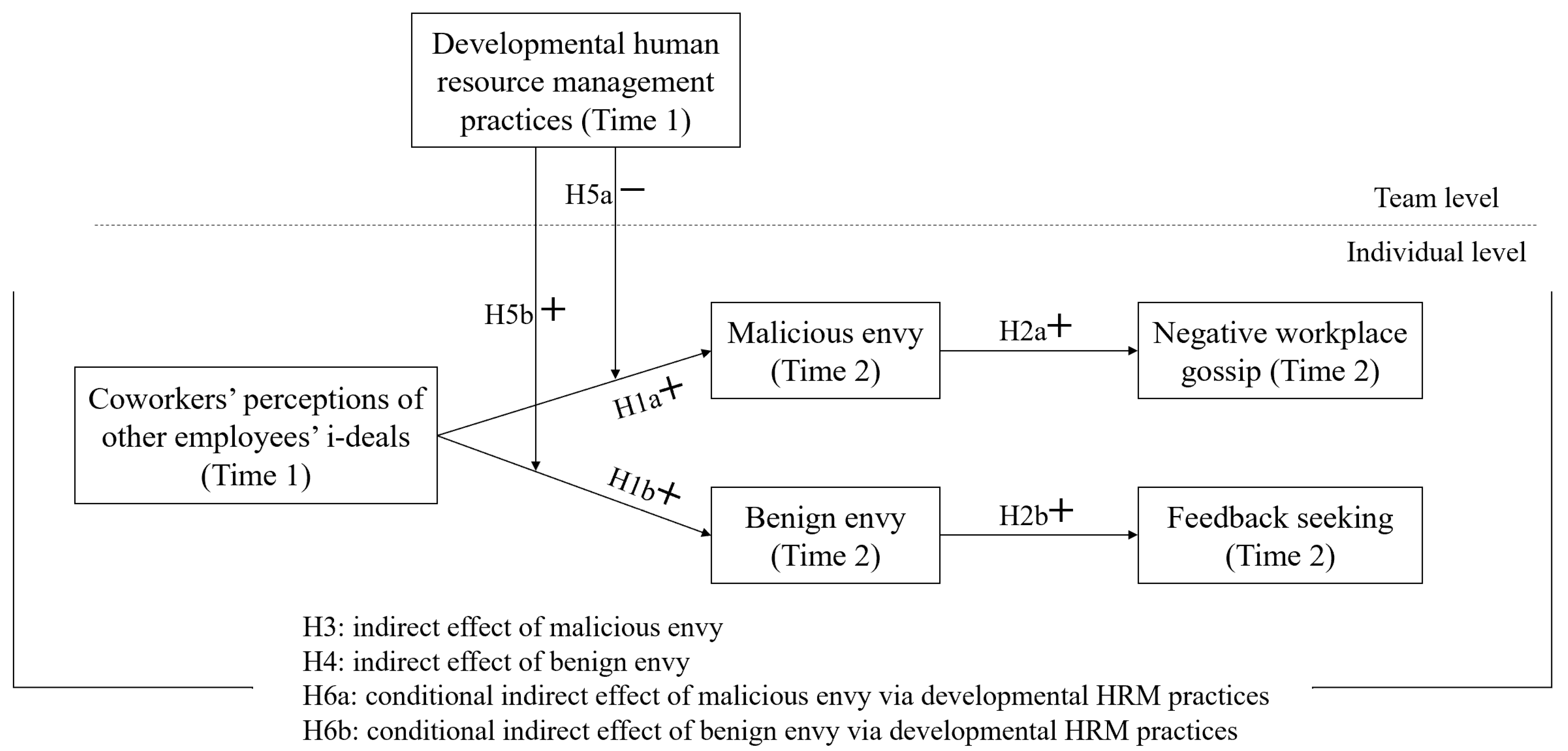

38]. This can range from malicious envy, resulting in negative workplace gossip behavior, to benign envy, which encourages coworkers to seek feedback. In this study, we explore the double-edged effects of CPOEID on coworker exchanges using malicious and benign envy, drawing on social comparison theory.

We recognize the importance of personalized management policies to reward high-performing employees, but we must also invest in the human capital of ordinary staff by implementing developmental HRM practices to ensure sustainable business development. Our study seeks to answer the question of whether differentiation and standardized HRM practices are complementary. Specifically, can standardized HRM practices maximize the positive performance-enhancement effects of i-deals (e.g., encouraging feedback-seeking behavior) while minimizing the potential for misunderstanding and rejection (e.g., reducing negative workplace gossip)? Developmental HRM practices are designed to satisfy employees’ needs [

39], empower them, and emphasize the importance of improving their abilities, work values, and sense of achievement [

40]. Its provision of management practices such as compensation, benefits, training, and promotion can satisfy the needs of the majority of employees [

12]. I-deals are used to supplement a few select talented employees with specialized knowledge, skills, and unique characteristics, which can help reduce coworkers’ negative confrontation and motivate bystanders to view i-deals in a positive light [

15]. Consequently, we sought to examine how standardized HRM policies can either reduce the negative effects of differentiated HRM policies or support their positive effects, using developmental HRM practices as moderators.

Our study offers two primary contributions to the research field of differentiated HRM policies and their impact on coworkers’ interactive behaviors. First, we systematically examined the managerial effects of differentiated HRM policies from a bystander perspective, exploring both the beneficial and detrimental outcomes [

16]. We respond to Kong et al.’s call for enriching negative outcomes of i-deals [

26]. To this end, we explored the mediating role of binary envy, i.e., benign envy and malicious envy [

41]. We empirically tested Marescaux et al.’s suggestion to integrate the contrast and assimilation effects [

42]. The contrast effect is consistent with the findings of previous studies [

22,

34,

35,

36,

43] that cite malicious envy as a potential precursor to “cold violence” behavior in the workplace [

28]. The assimilation effect echoes Lee and Duffy’s research, which suggests exploring the positive effects of workplace envy [

44]. Second, we provide empirical support for the complementarity of differential and standardized HRM practices as we explore the impact of organizational policies on employee workplace outcomes. We respond to Anand et al.’s call to examine how pervasive HRMPs can mitigate the dysfunctional outcomes of i-deals [

12], providing a comprehensive understanding of the role of management policies on employees’ implicit emotions and explicit behaviors. Specifically, we examine the moderating role of developmental HRM practices and provide supporting evidence that developmental HRM practices contribute to employees’ psychological well-being [

45,

46], i.e., that developmental HRM practices are effective in reducing their negative emotions.

5. Discussion

An investigation was conducted to explore the effects of CPOEID on coworker interactions, using social comparison theory as a framework, with envy as the mediator and developmental HRM practices as the moderator. An empirical study of 108 teams and 546 employees yielded the following key findings:

We systematically examined the managerial effectiveness of differentiated HRM policies from a bystander perspective, exploring both functional and dysfunctional outcomes. Prior research has explored the effects of i-deals on i-dealers’ cognition, affect, behavior, and performance [

7,

30], but this does not provide a comprehensive measure of the effects of differentiated management policies. Therefore, we sought to explore the exemplary effect of i-dealers and investigate how i-deals support bystanders in their self-improvement efforts [

17], while also avoiding disruptive interpersonal interaction behaviors of bystanders to protect i-dealers from reputational damage. Our findings showed that CPOEID had a positive effect on coworkers’ negative workplace gossip (0.247 **) and feedback seeking (0.147 **), echoing Kong et al.’s call for enriching negative outcomes for i-deals [

26]. Additionally, we tested the conjecture that i-dealers with nonmarginalized multi-organizational support are vulnerable to negative workplace gossip [

28], as well as the performance-promoting effects of i-deals on bystanders.

To this end, we investigated the mediating role of both malicious and benign envy based on social comparison theory. Previous studies have primarily concentrated on the contrast effect of social comparison in a monadic framework of envy [

34,

35]. However, this framework is not suitable for complex emotions such as envy [

41,

62], and it is necessary to distinguish between benign and malicious forms [

78]. We empirically tested Marescaux et al.’s suggestion to integrate the contrast and assimilation effects of CPOEID [

42]. On the one hand, we explored the mediating role of malicious envy (indirect effect: 0.098 **) in support of Hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3, indicating that CPOEID indirectly affects negative workplace gossip through malicious envy. This contrast effect is consistent with findings from previous studies [

22,

34,

35,

36,

43] indicating that malicious envy can lead to a form of “cold violence” behavior in the workplace [

28]. Coworkers may use negative workplace gossip to damage i-dealers’ reputations, weaken the performance of targets, and reduce their own feelings of inferiority. On the other hand, we found evidence to support Hypotheses 1b, 2b, and 4, suggesting that CPOEID indirectly affects feedback-seeking through the mediating role of benign envy (indirect effect: 0.050 *). This assimilation effect echoes the findings of Lee and Duffy [

44], who suggest that the positive effects of workplace envy be explored. Individuals seek feedback from i-dealers for self-improvement, either through direct inquiry or indirect observation. Our research further enriches our understanding of the antecedent variables of feedback seeking from an individual’s emotional perspective [

79].

More importantly, we provide empirical support for the complementarity of differential and standardized HRM practices and explore how their interaction affects employee workplace outcomes. Traditional standardized management policies carry the underlying assumption that employee competence and performance are equal and evenly distributed [

17]. However, this is not the case; research from O’Boyle and Aguinis demonstrates that employees with higher levels of knowledge and use capabilities have higher performance levels [

80]. As such, organizations must use targeted management policies to attract, motivate, and retain these talented employees. Previous studies have only looked at the effects of the two types of HRM practices on employee outcomes separately, without considering their interaction. To address Anand et al.’s call to examine how pervasive HRM practices can mitigate the dysfunctional outcomes of i-deals [

12], we provide a comprehensive understanding of the role of management policies on employees’ implicit emotions and explicit behaviors. Additionally, we examine the moderating role of developmental HRM practices and expand the boundary conditions of i-deals by combining broad organizational support for all employees with specific support for those who demonstrate talent, to assess the impact of developmental HRM practices on emotional activation.

Specifically, developmental HRM practices weaken both the effect of CPOEID on malicious envy (−0.077 *, supporting Hypothesis 5a) and the mediating effect of malicious envy between CPOEID and negative workplace gossip (indirect effect difference: −0.063 *, supporting Hypothesis 6a). The same practices also have a negative moderating effect on the relationship between CPOEID and benign envy (−0.105 **, rejecting Hypothesis 5b), weakening the mediating role of benign envy between CPOEID and feedback seeking (indirect effect difference: −0.045 *, rejecting Hypothesis 6b). It is possible that developmental HRM practices can contribute to the psychological well-being of employees [

45,

46], which could ultimately help to reduce their negative emotions. Envy is a negative emotion that may be triggered when someone compares themselves to another person who has something they desire [

32,

33]. Although it can act as a catalyst for self-improvement, benign envy can still be a painful emotion to experience [

41,

62]. Upward social comparison can have a range of effects, including both detrimental emotions like envy, and beneficial emotions like admiration [

81]. Implementation of higher levels of developmental HRM practices, which provide compensation, benefits, training, and promotion, can meet the needs of most employees [

12]. These adequate external supports can facilitate coworkers in understanding the investment implications of individual agreements [

22], thus promoting a better understanding of the gap between coworkers and i-dealers. This understanding can lead to increased satisfaction with the support received, admiration for the expertise of i-dealers, and a reduction in distress and envy.

5.1. Practical Implications

Our research offers practical insights for managers when introducing differentiated HRM policies. It is essential that managers do not forsake generic HRM practices. I-deals can be a powerful tool to harness the influence of “star employees” such as i-dealers [

17]. However, the negative feelings of coworkers (such as a sense of unfairness and malicious envy) can severely reduce the effectiveness of individual agreements, leading to a “lose-lose-lose” or “win-win-lose” situation [

15]. Managers should strike a balance between differentiated and universal HRM practices to effectively utilize i-deals to attract, motivate, and retain talented employees [

23], while also fulfilling the autonomy and achievement needs of coworkers. Envy has a small role in motivating self-improvement, but it is not necessary to sacrifice employees’ mental health and workplace relationships for the sake of improving employee performance. Managers should implement developmental HRM practices in terms of diversified training, development evaluation, job design, and communicating feedback to reduce hostility and friendly rivalry caused by different HRM practices.

While dealing with coworkers, managers should weaken their malicious envy and stifle the growth of negative gossip in the workplace. The importance of i-dealers to the organization is obvious to all; managers can increase i-dealers’ resources and give them rewards such as increased salaries and promotions. However, care must nevertheless be taken to avoid exhibiting an excessive preference for i-dealers. Simultaneously, managers must improve the level of mutual understanding among team members, enhance team cohesion, and stifle the growth of negative gossip in the workplace at its source. Additionally, managers should make reasonable use of employees’ benign envy and encourage them to actively seek feedback. It is unnecessary to avoid social comparisons among employees entirely [

42], and managers can even motivate employees to do so in a reasonable way, such as by giving honorary rewards to i-dealers, identifying them as models for team learning, and encouraging employees to actively use i-dealers as benchmarks to improve themselves. Managers should also create a supportive feedback atmosphere, reduce employees’ withdrawal due to improper inquiries, and promote feedback inquiry among employees and between employees and leaders to become an organizational norm.

More importantly, our study provides important lessons for the implementation of HRM policies to achieve the sustainable development of enterprises. Talent acquisition has become a key tool for Chinese firms to ensure long-term growth and promote innovation [

82]. Unfortunately, many enterprises have historically used i-deals policies that focus solely on the development of talented employees, neglecting the reactions of coworkers, teams, and organizations and resulting in unsuccessful talent acquisition. This study examines the management effectiveness of i-deals from a bystander’s perspective, encouraging enterprises to use supportive measures, such as developmental HRM practices, when implementing talent management. This maximizes the exemplary role of i-dealers and mitigates misunderstandings and rejections from bystanders, ultimately benefiting individuals (both beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries of i-deals), teams, and organizations by helping enterprises meet their goal of introducing talents to foster innovation.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

The present study offers valuable insights and directions for future research that have meaningful implications from both theoretical and practical perspectives. However, we acknowledge the limitations of the study and suggest potential ways to address them. Specifically, although this time-lag study used supervisor–subordinate pairing to collect data, which could effectively allow us to control for endogeneity, the causal relationships within the data could not be verified. To further improve the explanatory power of the model, future research could use experimental manipulations. Additionally, this study explored the double-edged effect of CPOEID on coworkers’ emotions and behaviors, and future research could enrich the results concerning interpersonal interactions further based on cognitive or motivational mechanisms. Furthermore, this study explored the envy-induced behavioral responses exhibited by coworkers, such as negative workplace gossip or feedback-seeking but did not investigate the emotional and behavioral responses of the envied persons. Future research could integrate the perspectives of both the envier and the envied to explore the strategies that the envied person could use to mitigate their own emotions and those of the envier [

50]. This study investigated the moderating role of developmental HRM practices, offering empirical evidence that pervasive HRM practices can compensate for the limitations of differentiated HRM practices. Future research could further explore how strategic HRM practices, such as high-performance work systems and high-commitment work systems, interact with i-deals. Finally, given that i-dealers typically possess specialized knowledge or skills [

83], there may be a transfer of tacit knowledge within the team from the recipients to the bystanders. Future research should examine the effects of i-deals on knowledge management within teams, particularly the role of i-deals in facilitating bystander knowledge acquisition and hiding behavior and the moderating impact of receiver knowledge sharing.