Investigating the Relationships among High-Performance Organizations, Knowledge-Management Best Practices, and Innovation: Evidence from the Greek Public Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Investigation of the relationship between knowledge management (KM) and innovation in the public sector;

- High-performance organizations—HPO investigation as a contextual factor which affects KM practices and innovation in the public sector;

- Holistic investigation of the relationships among KM, innovation, and HPOs in the Greek public sector.

2. Literature Review

2.1. KM Best Practices

KM in the Public Sector

2.2. HPOs

HPO in the Public Sector

2.3. Organizational Innovation

Organizational Innovation in the Public Sector

2.4. The Relationship among KM Best Practices, HPOs, and Organizational Innovation

2.4.1. KM Best Practices and Organizational Innovation

2.4.2. HPO and KM Best Practices

2.4.3. HPOs and Organizational Innovation

2.4.4. HPO, KM Best Practices and Organizational Innovation

3. Research Methods

3.1. The Research Instrument

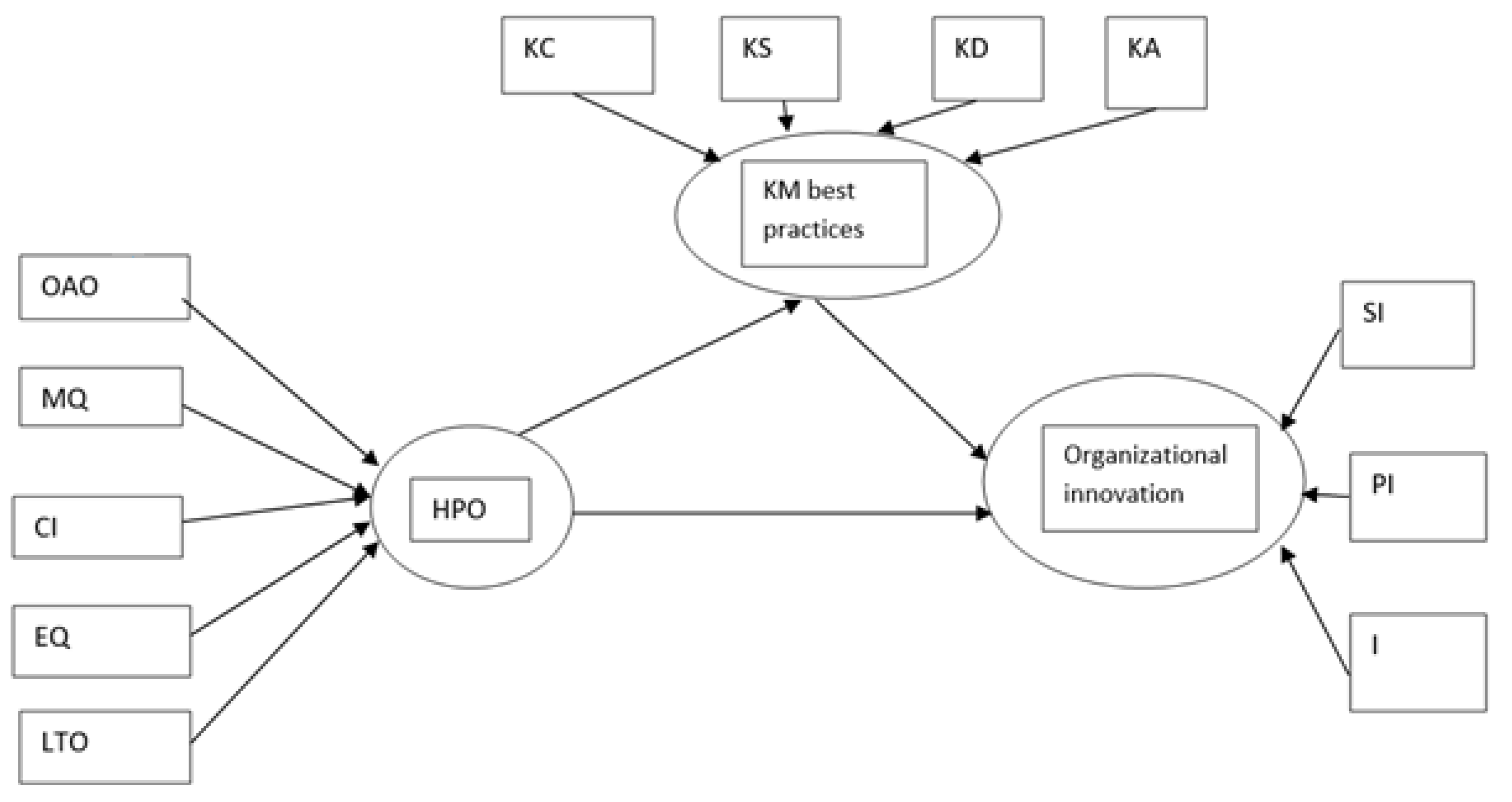

- 35 questions for “HPO” [39] that refer to MQ (management quality), OAO (openness and action orientation), LTO (long-term orientation), CI (continuous improvement), and EQ (employee quality);

- 15 questions for “organizational innovation” [21] that refer to SI (structural innovation), PI (process innovation), and I (competence innovation).

3.2. The Sample

3.3. The Validity Assessment

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Obeidat, B.Y.; Al-Suradi, M.M.; Masa, E.; Tarhini, A. The impact of knowledge management on innovation: An empirical study on Jordanian consultancy firms. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1214–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ahbabi, S.A.; Singh, S.K.; Balasubramanian, S.; Gaur, S.S. Employee perception of impact of knowledge management processes on public sector performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 23, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagorogoza, J.K.; Herik, J.V.D.; Waal, A.D.; Walle, B.V.D. The mediating effect of knowledge management in the relationship between the HPO framework and performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2023; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.K.; Oliveira, M.; Curado, C. Linking knowledge management processes to innovation: A mixed-method and cross-national approach. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 43, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqdliyan, R.; Setiawan, D. Antecedents and consequences of public sector organizational innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Peruta, M.R.; Del Giudice, M.; Lombardi, R.; Soto-Acosta, P. Open innovation, product development, and inter-company relationships within regional knowledge clusters. J. Knowl. Econ. 2018, 9, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waal, A. Creating high-performance organizations in Asia: Issues to consider. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Res. 2020, 7, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.T.; Mai, N.K. High-performance organization: A literature review. J. Strategy Manag. 2020, 13, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, S.; Kessopoulou, E.; Tsiotras, G. KM tools alignment with KM processes: The case study of the Greek public sector. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2023, 21, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amber, Q.; Khan, I.A.; Ahmad, M. Assessment of KM processes in a public sector organisation in Pakistan: Bridging the gap. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2018, 16, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, M.S.; Jain, K.K.; bte Ahmad, I.U.K. Knowledge sharing among public sector employees: Evidence from Malaysia. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2011, 24, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titi Amayah, A. Determinants of knowledge sharing in a public sector organization. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 454–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed-Ikhsan, S.O.S.; Rowland, F. Knowledge management in a public organization: A study on the relationship between organizational elements and the performance of knowledge transfer. J. Knowl. Manag. 2004, 8, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, J.P.; McIntyre, S. Knowledge management modeling in public sector organizations: A case study. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2010, 23, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waal, A.A. The characteristics of a high performance organisation. Bus. Manag. Strategy 2012, 3, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waal, A.A. Achieving High Performance in the Public Sector. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2010, 34, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, D.A.; Buick, F.; O’Donnell, M.; O’Flynn, J.L.; West, D. Developing high performance: Performance management in the Australian Public Service. SSRN Electron. J. 2012, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Waal, A.A. The secret of high performance organizations. Manag. Online Rev. 2008, 2, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, M.A.; Kalimullah; Khan, S.; Shahid, Z. High performance organisation: The only way to sustain public sector organisations. Int. J. Public Sect. Perform. Manag. 2020, 6, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbeto, D.L.; Hon, A.H. Market turbulence and service innovation in hospitality: Examining the underlying mechanisms of employee and organizational resilience. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 1119–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafabi, S.; Munene, J.; Ntayi, J. Knowledge management and organisational resilience: Organisational innovation as a mediator in Uganda parastatals. J. Strategy Manag. 2012, 5, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. The development and validation of the organisational innovativeness construct using confirmatory factor analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2004, 7, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.S. Losing innovativeness: The challenge of being acquired. Manag. Decis. 2006, 44, 1161–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, U.U.; Iqbal, A. Nexus of knowledge-oriented leadership, knowledge management, innovation and organizational performance in higher education. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2020, 26, 1731–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijal-Moghrabi, I.; Sabharwal, M.; Ramanathan, K. Innovation in public organizations: Do government reforms matter? Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2020, 33, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.; Hartley, J. Innovations in governance in The New Public Governance. In Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Government; Osborne, L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Enhancing collaborative innovation in the public sector. Adm. Soc. 2011, 43, 842–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfing, J.; Triantafillou, P. Enhancing Public Innovation by Transforming Public Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Demircioglu, M.A.; Audretsch, D.B. Conditions for innovation in public sector organizations. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.S.; Anumba, C.J.; Carrillo, P.M.; Al-Ghassani, A.M. STEPS: A knowledge management maturity roadmap for corporate sustainability. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2006, 12, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. Knowledge management: Theoretical and methodological foundations. In Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development; Smith, K.G., Hitt, M.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Gloet, M. Knowledge management and the links to HRM: Developing leadership and management capabilities to support sustainability. Manag. Res. News 2006, 29, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, N.; Ghobadian, A. The importance of capabilities for strategic direction and performance. Manag. Decis. 2004, 42, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagorogoza, J.; de Waal, A. The role of knowledge management in creating and sustaining high performance organisations: The case of financial institutions in Uganda. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualoush, S.; Bataineh, K.; Alrowwad, A.a. The role of knowledge management process and intellectual capital as intermediary variables between knowledge management infrastructure and organization performance. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 13, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masa’deh, R.E.; Obeidat, B.Y.; Tarhini, A. A Jordanian empirical study of the associations among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, knowledge sharing, job performance, and firm performance: A structural equation modelling approach. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 681–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroueh, M.; de Waal, A. Applicability of the HPO framework in non-profit organizations: The case of the Emirates Insurance Association. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; de Waal, A. Comparison of Indian with Asian organizations using the high performance organization framework: An empirical approach. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2020, 25, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Wende, S.; Becker, J. SmartPLS 3. Available online: www.smartpls.com (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Hair, J.; Matthews, L.; Matthews, R.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, A.; Agrawal, R. Scale development and modeling of intellectual property creation capability in higher education. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020, 21, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Team learning in interdisciplinary research teams: Antecedents and consequences. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 1429–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraies, S.; Zine El Abidine, S. Do leadership styles promote ambidextrous innovation? Case of knowledge-intensive firms. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 836–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, G.; Mardani, A.; Senin, A.A.; Wong, K.Y.; Sadeghi, L.; Najmi, M.; Shaharoun, A.M. Relationship between culture of excellence and organisational performance in Iranian manufacturing companies. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihail, D.M.; Kloutsiniotis, P.V. Modeling patient care quality: An empirical high-performance work system approach. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 1176–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrénit, G. Building technological capabilities in latecomer firms: A review essay. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2004, 9, 209–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Questions | Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPO | CI1 | My organization has adopted a strategy that clearly differs from that of other organizations | 0.631 |

| CI2 | In my organization, processes are continuously improved | 0.870 | |

| CI3 | In my organization, processes are continuously simplified | 0.827 | |

| CI4 | In our organization, processes are constantly aligned/synchronized with the organizational goals and strategies. | 0.860 | |

| CI5 | In my organization, anything related to organizational performance that occurs is explicitly reported | 0.791 | |

| CI6 | In my organization, both financial and non-financial information is communicated to its members | 0.568 | |

| CI7 | My organization constantly innovates in terms of its core competencies (e.g., collaboration, communication, leadership and organizational skills, problem-solving abilities, flexibility, etc.) | 0.869 | |

| CI8 | My organization continually innovates regarding its services and processes | 0.856 | |

| OAO1 | The management of our organization frequently engages in a dialogue with employees | 0.862 | |

| OAO2 | Organizational members spend much time on communication, knowledge exchange and learning | 0.822 | |

| OAO3 | Organizational members are always involved in important processes | 0.812 | |

| OAO4 | The management of our organization allows making mistakes. | 0.744 | |

| OAO5 | The management of our organization welcomes change | 0.829 | |

| OAO6 | Our organization is performance driven | 0.820 | |

| MQ1 | The management of our organization is trusted by organizational members | 0.755 | |

| MQ2 | The management of our organization has integrity | 0.825 | |

| MQ3 | The management of our organization is a role model for organizational members | 0.858 | |

| MQ4 | The management of our organization applies fast decision-making | 0.857 | |

| MQ5 | The management of our organization applies fast action taking | 0.809 | |

| MQ6 | The management of our organization coaches organizational members to achieve better results | 0.772 | |

| MQ7 | The management of our organization focuses on achieving results | 0.753 | |

| MQ8 | The management of our organization is very effective | 0.692 | |

| MQ9 | The management of our organization applies strong leadership | 0.751 | |

| MQ10 | The management of our organization is confident | 0.802 | |

| MQ11 | The management of our organization is decisive with regard to non-performers | 0.771 | |

| EQ1 | The management of our organization always holds organizational members responsible for their results | 0.889 | |

| EQ2 | The management of our organization inspires organizational members to accomplish extraordinary results | 0.897 | |

| EQ3 | Organizational members are trained to be resilient and flexible | 0.736 | |

| EQ4 | Our organization has a diverse and complementary workforce | 0.732 | |

| LTO1 | Our organization grows through partnerships with suppliers and/ or customers | 0.842 | |

| LTO2 | Our organization maintains good and long-term relationships with all stakeholders | 0.853 | |

| LTO3 | Our organization is aimed at servicing the customers as best as possible | 0.817 | |

| LTO4 | The management of our organization has been with the company for a long time | 0.714 | |

| LTO5 | New management is promoted from within the organization | 0.812 | |

| LTO6 | Our organization is a secure workplace for organizational members | 0.802 | |

| KM best practices | KC1 | My organization has official or unofficial processes for generating new knowledge from existing knowledge (implicit individual and/or explicit organizational) | 0.859 |

| KC2 | My organization has official or unofficial processes for acquiring knowledge about new services or processes in the public sector | 0.853 | |

| KC3 | My organization has official or unofficial processes and provides the necessary Knowledge Management (KM) tools (technological and non-technological) for creating new knowledge from external sources (e.g., consultants, other organizations within the country or abroad) | 0.894 | |

| KC4 | My organization has official or unofficial processes and provides the necessary KM tools (technological and non-technological) for acquiring knowledge related to best practices from other public organizations (in Greece or internationally) that lead to performance improvement | 0.873 | |

| KC5 | My organization has official or unofficial processes and provides the necessary KM tools (technological and non-technological) for acquiring knowledge about the needs, requirements, and desires of its customers (citizens, businesses, and other stakeholders) | 0.860 | |

| KC6 | My organization has teams responsible for identifying best practices. | 0.795 | |

| KS1 | In my organization, there are archived organizational processes in the forms of forms, procedures, work guides, written protocols, manuals, etc | 0.837 | |

| KS2 | Lists with comprehensive employee details (such as phone numbers, emails, organization, department, responsibilities) are available, indicating specific knowledge areas, making it easy to find the right person for acquiring required knowledge and completing tasks | 0.827 | |

| KS3 | Updated databases and information renewal are in place | 0.779 | |

| KS4 | My organization uses KM tools (technological and non-technological) to detect new ideas from its employees and store them for further development | 0.741 | |

| KS5 | My organization has mechanisms and tools for storing knowledge from employees, citizens, businesses, and partners | 0.811 | |

| KD1 | Employees in my organization are often encouraged to engage in informal discussions to share knowledge among themselves | 0.859 | |

| KD2 | Knowledge sharing is encouraged among individuals within my organization | 0.803 | |

| KD3 | Individuals are interested in knowing the knowledge and skills possessed by their colleagues | 0.698 | |

| KD4 | My organization has processes and uses tools to disseminate knowledge within the organization | 0.885 | |

| KD5 | My organization has processes and uses tools to disseminate knowledge outside the organization (e.g., among other public organizations within and outside Greece) | 0.780 | |

| KA1 | My organization has official or unofficial processes and utilizes the necessary KM tools to apply knowledge generated through learning from relevant past experiences to address shortcomings | 0.869 | |

| KA2 | Employees are encouraged to apply their knowledge using KM tools to solve problems that arise in their daily activities | 0.874 | |

| KA3 | My organization swiftly responds to citizens’ demands by utilizing KM tools | 0.861 | |

| KA4 | My organization possesses the necessary KM tools to remain flexible and ready to adapt its services according to prevailing circumstances | 0.892 | |

| Organizational innovation | SI1 | We are redesigning different strategies to achieve our goals | 0.863 |

| SI2 | We are revising the functions of departments within our organization | 0.817 | |

| SI3 | We evaluate performance plans within our organization | 0.860 | |

| SI4 | We improve our systems concerning risk management | 0.868 | |

| SI5 | We review our programs | 0.908 | |

| SI6 | We revise job descriptions within our organization | 0.872 | |

| SI7 | We have succeeded in improving the methods of delivering our services | 0.843 | |

| PI1 | We are redesigning workflow using communication and information technology | 0.904 | |

| PI2 | We design the provision of services through the internet | 0.897 | |

| PI3 | We change workflow by removing specific activities | 0.848 | |

| PI4 | We change workflow by merging specific activities | 0.819 | |

| I1 | We improve leadership behavior | 0.822 | |

| I2 | We improve our behavior in serving citizens | 0.817 | |

| I3 | We create new networks for our organization | 0.882 | |

| I4 | We change our behavior regarding the management of organizational resources we possess | 0.862 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KM | 0.924 | 0.946 | 0.814 |

| HPO | 0.938 | 0.953 | 0.801 |

| INNOVATION | 0.923 | 0.951 | 0.866 |

| Fornell-Lacker Criterion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| KM | HPO | INNOVATION | |

| KM | 0.902 | ||

| HPO | 0.833 | 0.895 | |

| INNOVATION | 0.785 | 0.804 | 0.931 |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| KM | HPO | INNOVATION | |

| KM | |||

| HPO | 0.894 | ||

| INNOVATION | 0.845 | 0.861 |

| SSO | SSE | Q2 (= 1 − SSE/SSO) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KM | 1080.000 | 475.958 | 0.559 |

| HPO | 1350.000 | 1350.000 | 0.00 |

| INNOVATION | 810.000 | 336.263 | 0.585 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPO→KM→INNOVATION | 0.314 | 0.315 | 0.058 | 5.395 | 0.000 |

| KM→INNOVATION | 0.377 | 0.377 | 0.068 | 5.522 | 0.000 |

| HPO→KM | 0.833 | 0.833 | 0.020 | 42.379 | 0.000 |

| HPO→INNOVATION | 0.804 | 0.804 | 0.027 | 29.918 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xanthopoulou, S.; Tsiotras, G.; Kafetzopoulos, D.; Kessopoulou, E. Investigating the Relationships among High-Performance Organizations, Knowledge-Management Best Practices, and Innovation: Evidence from the Greek Public Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813810

Xanthopoulou S, Tsiotras G, Kafetzopoulos D, Kessopoulou E. Investigating the Relationships among High-Performance Organizations, Knowledge-Management Best Practices, and Innovation: Evidence from the Greek Public Sector. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813810

Chicago/Turabian StyleXanthopoulou, Styliani, George Tsiotras, Dimitrios Kafetzopoulos, and Eftychia Kessopoulou. 2023. "Investigating the Relationships among High-Performance Organizations, Knowledge-Management Best Practices, and Innovation: Evidence from the Greek Public Sector" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813810

APA StyleXanthopoulou, S., Tsiotras, G., Kafetzopoulos, D., & Kessopoulou, E. (2023). Investigating the Relationships among High-Performance Organizations, Knowledge-Management Best Practices, and Innovation: Evidence from the Greek Public Sector. Sustainability, 15(18), 13810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813810