1. Introduction

The degree of industrial development had traditionally been the standard for measuring a nation’s economic strength [

1]. Industrial revolutions have changed the world pattern [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6], and some former developing countries have learned and followed the advanced industrial technology of the West to improve their national power [

7,

8]. In the 1970s, industry-led countries, like the United States and many European countries, entered a post-industrial society [

9]. As a result of post-industry, de-industrialization, the phenomenon of closing factories, and losing jobs became the norm [

10,

11,

12], and this existence has had a global impact [

13,

14]. Indeed, free trade and the removal of trade barriers have allowed companies to move production virtually anywhere in the world [

15]. Thus, companies in developed countries have, primarily to reduce labor costs, moved manufacturing and production to low-wage areas [

11,

16,

17,

18]. This provided an opportunity for China, which was in the process of reform and opening-up, to gradually develop into the “factory of the world” and become well-known worldwide for its “Made in China” image [

19]. Recently, with the “Industry 4.0” era, China is transforming from “Made in China” to “Created in China” [

20,

21].

The industrial leadership of the West and sensitive approaches to conservation, adopted from the 1970s onward, have led to a number of outstanding transformed industrial projects. Somewhat later, China’s path toward the revitalization of abandoned industrial buildings began in the 21st century [

22]. China’s rapid development in recent years has led to numerous obsolete industrial buildings, and these are providing a new platform and practical opportunity for their reuse. From the beginning of the modern industry in the 1860s to the current period of leading the world in “Industry 4.0”, China has a vast amount of old industrial buildings resulting from the renewal of industrial manufacturing. This now provides an exciting opportunity and a valuable resource for future urban regeneration [

23,

24]. According to the National Development and Reform Commission of China, between 2013 and 2022, over 120 old industrial cities will be restructured, covering a total area of 140 km

2 and a population of 390 million.

In recent years, especially in countries with such rapid development as China, excessive urbanization has led to regional homogenization and the loss of the city’s individuality [

25,

26]. For citizens, homogenized cityscapes and cultures are dominant factors in aesthetic fatigue [

26]. These old buildings that remain in the city are responsible for maintaining the cultural identity. The reuse of industrial heritage can not only adapt and meet the needs of contemporary citizens, but also preserve the historical characteristics of the region and stimulate the public’s aesthetic in an attractive way [

23]. What is more important is that the transmission of culture relies on the public, and the revitalization of industrial heritage under cultural guidance should be recognized by the public [

27]. Are the transformations of industrial heritage really the way the public wants them to be? From the view of designers, they work hard to create good works. The expression of architecture, however, is not as straightforward as the text, and a conflict arises between the users and the designers [

23]. Therefore, the research is to show what the needs of the users are, in order to eliminate this conflict.

Currently, the transformation of abandoned industrial heritage is still designer-led [

28]. The expertise of the designer of industrial heritage reuse is not only in the preservation and expression of historical culture, but also, more importantly, in the need for the designer to understand the continuously changing needs of the users of the project [

23]. In this way, the designer’s work will be attractive and have vitality in the city; after all, architecture is meant to serve people. Therefore, how designers can understand the public’s thoughts and needs, and how the reuse of industrial heritage can meet the public’s taste will be the main research question.

A survey and analysis of 1933 Old Millfun in Shanghai, China, will be used to illustrate the evaluation and suggestion process. The research begins with an interview survey of the project. This will be used as a database for the study after uncovering how visitors evaluate the project. According to the data, a fuzzy modeling and structural analysis will be established to accommodate this project. The fuzzy theory is able to convert qualitative evaluation data to quantitative data [

23,

29,

30]. The results of the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method are inscribed in a set and not a point, which is considered to count the combined convergent outcomes of multiple individuals [

30]. This helps to reflect a consistent evaluation of the project by a number of visitors, and is therefore considered to be a valid statistical method for reflecting public perceptions (rather than individuals) [

23,

29]. After knowing the public comments on the evaluation, the strengths and weaknesses of the project could be clear. Finally, an effective development proposal can be made for 1933 Old Millfun. The research can not only model and demonstrate the evaluation process for 1933 Old Millfun, but also provide an approach for future evaluations and suggestions for similar projects.

2. The Cultural Expression of Reused Industrial Heritage

Industrial culture is abstract, and it is a comprehensive subject that involves many aspects [

23,

31,

32,

33,

34]. It is defined as a dynamic phenomenon in which past and present industrial manufacturing are embedded in the human physical environment, social structures, cognitive abilities, and institutions [

35]. Culture is a boundless concept; almost all human activities can be considered to be a culture or are driven by culture [

33,

34,

36]. Industrial culture encompasses a wide range of aspects, including: architecture, technology, design, machinery, tools, artifacts, and social history [

37]. These elements hold historical significance and tell stories about the people who worked in these industrial sites [

23,

34,

36,

38,

39,

40,

41]. They provide a window into the past and allow people to understand the conditions and challenges of industrial labor. The industrial culture preserved in industrial heritage can therefore be seen as a record of history [

42].

Public acceptance will be strong evidence of historical and cultural value [

23,

43]. The public acceptance of industrial culture is a complex process that involves both nostalgia and the recognition of cultural heritage [

43,

44]. People have started to recognize that preserving industrial heritage is essential for understanding their history and culture [

45]. Industrial culture has become an opportunity to educate the public about the positive aspects of the industrial era, such as technological advancements and the progress of society. Museums and cultural spaces established at former industrial sites play a crucial role in engaging the public and creating a dialogue about industrial history. Exhibitions, workshops, and interactive displays help demystify industrial processes and foster a sense of pride and stimulate curiosity about the achievements of the industrial age [

23]. Furthermore, the growing popularity of industrial aesthetics also plays a significant role in the acceptance of industrial culture. The raw and utilitarian nature of industrial buildings and objects have become fashionable, influencing architecture, interior design, and fashion. Industrial-inspired spaces, such as lofts and co-working offices, have become symbols of creativity and entrepreneurship [

46].

For designers, the expression of industrial culture in industrial heritage reuse projects has become the foundation for public acceptance of industrial culture. Exploring how industrial heritage buildings serve as a platform for cultural expression, reflecting the values, traditions, and stories of a bygone era, is important. Expressing culture through industrial heritage reuse requires a multidimensional approach. Various methods and strategies for expressing culture through industrial heritage reuse have already been formed, which are summarized as follows:

Preserving and restoring the original features of industrial heritage sites is crucial to maintaining their cultural significance. This includes repairing and maintaining the structural integrity of buildings, restoring historical artifacts, and preserving the overall ambiance of the site [

45]. By doing so, the cultural value of the industrial heritage is retained, and visitors can fully immerse themselves in the historical context.

Adaptive reuse involves repurposing industrial heritage sites to serve new functions while respecting their cultural value [

47]. These adaptive reuse projects allow for the integration of contemporary development requirements while paying homage to the site’s industrial past. The integration of old and new creates a unique cultural experience for visitors [

48].

Industrial heritage buildings serve as conduits for historical narratives, enabling us to understand the socioeconomic and cultural changes brought about by industrialization. By telling compelling stories about the people, technologies, and social impact of the industrial era, the cultural narrative is enriched, allowing visitors to connect emotionally with the site [

49].

To fully engage the public and encourage active exploration, many reused industrial heritage buildings offer interactive and hands-on experiences. Visitors can participate in workshops, demonstrations, and guided tours, allowing them to appreciate the industrial culture through physical interaction [

50]. Engaging in activities like operating machinery or assembling products from the era enhances the learning experience, making it more enjoyable and memorable.

Reused industrial heritage buildings also play a crucial role in promoting awareness and education about industrial culture. Through hosting exhibitions, workshops, conferences, and educational programs, these buildings become platforms for sharing knowledge and fostering a deeper understanding of the industrial past [

51]. By engaging schools, universities, and community organizations, industrial heritage sites can contribute to regional development, creating a knowledgeable and appreciative society.

Collaborating with various stakeholders, including government bodies, private entities, and cultural organizations, can strengthen the expression of culture through industrial heritage reuse. Public–private partnerships can provide access to expertise, funding, and resources that are instrumental in enhancing the cultural experience [

52]. Collaborations with artists, architects, and designers can present innovative ideas and transformative designs to the site, promoting cultural vibrancy [

53].

3. Research Method

3.1. Case Selection

The role of the designer is more like a teacher, the knowledge (heritage) is already there, and to be able to explain it to the students (public) vividly and comprehensively is an important value of a lecturer. Although methods and strategies for reusing industrial heritage have been developed after many years of exploration and practice, it is still necessary to adopt appropriate treatments for the cultural characteristics of a specific project. The study will evaluate whether industrial culture is accepted by the public in the case of the 1933 Old Millfun in Shanghai.

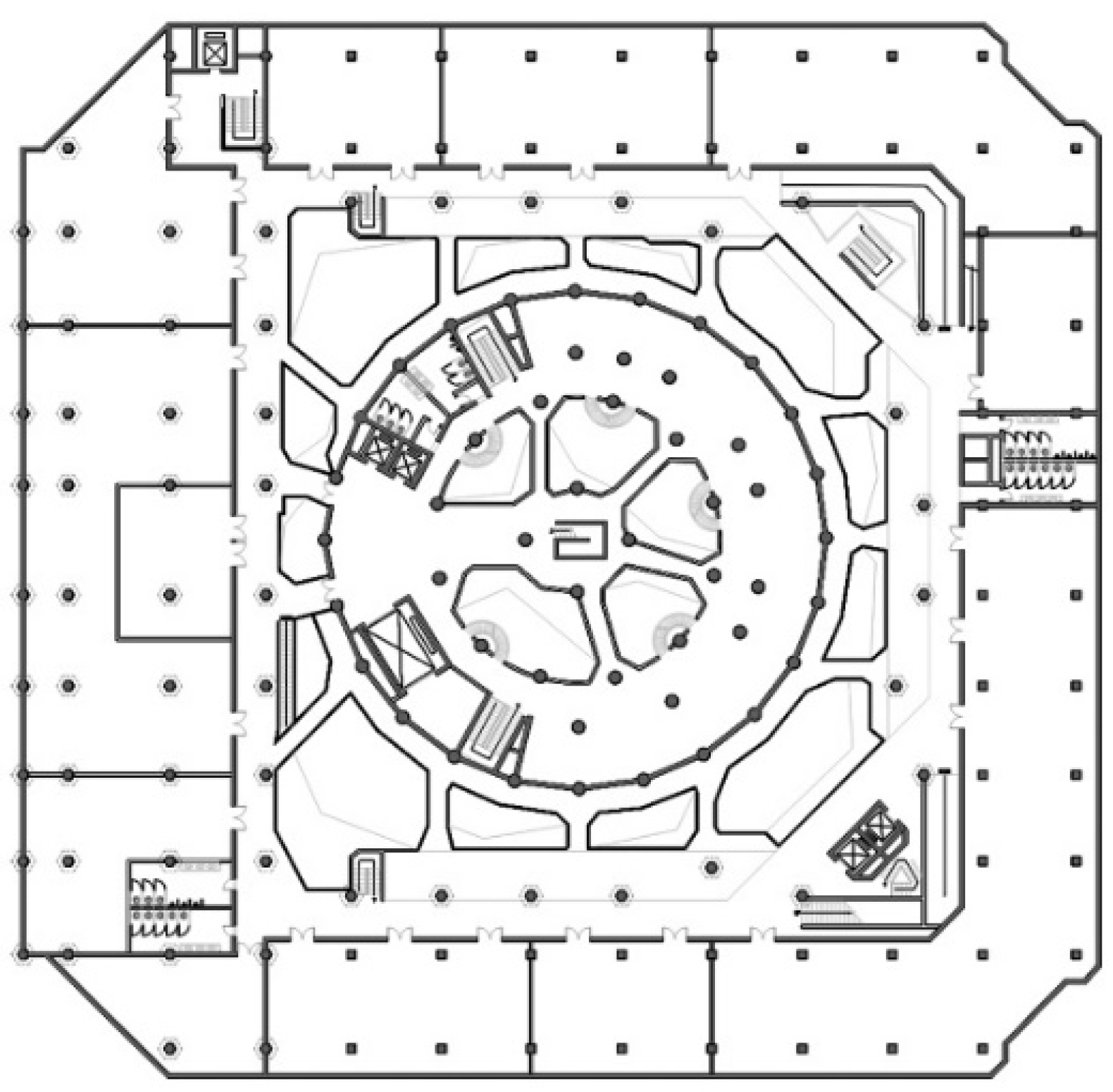

The 1933 Old Millfun was built in 1933, when Shanghai was in the era of International Settlement [

54,

55]. It was designed and built by a British team [

56], which shows the European style of architecture (

Figure 1). Its function was an abattoir and was primarily responsible for the supply of meat throughout Shanghai. The building is a reinforced concrete structure with a complex slaughter line (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The layout is that of multiple ring-shaped functional rooms around a central core. The two structures form independent spaces, with a series of bridges connecting and weaving together. In the 1940s, the abattoir could slaughter 300 cows, 100 calves, 300 pigs, and 500 sheep per day, making it the “No.1 slaughterhouse in the Far East” [

56]. At that time, there were only three slaughterhouses of such a scale in the world, one was in the UK, one was in the USA, and one was Shanghai: the 1933 Old Millfun.

In 2006, the project was transformed into a mixed-use building that includes retail, offices, exhibition, theatre, etc. Since the architecture and manufacturing techniques were at the top of the world at the time, which reflects the important value of the industrial heritage, the building’s structure and spaces have been preserved completely. Today, 1933 Old Millfun has been listed as an important industrial heritage in China; it relies on its industrial culture to attract a large number of tourists from all over China [

23]. It is not only a showcase of industrial culture, but also an example of the integration of industrial culture with the city’s contemporary function. With the help of the preserved industrial elements, it has successfully been developed into a number of cultural venues, such as weddings and conferences, product launches, design studios, etc. [

23,

54].

3.2. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method

The Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method is a systematic approach that combines both quantitative and qualitative analyses to assess and evaluate complex systems or situations. It involves applying fuzzy logic, a mathematical tool that deals with uncertainty and vagueness, to model and analyze the various factors and aspects involved [

57]. By introducing the concept of fuzziness, the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method allows for a more flexible and comprehensive assessment, considering multiple criteria and allowing for subjective judgments [

29]. It provides a framework for decision-makers to consider a range of possibilities and uncertainties, enabling them to make more informed and robust decisions. Fuzzy theory shows superiority in the transformation of imprecise knowledge through membership [

57,

58]. This method finds applications in various fields, including engineering, environmental sciences, economics, healthcare, and social sciences, where complex systems and multiple factors need to be taken into account for comprehensive evaluation and decision-making [

23,

29,

59].

The approach typically begins with the identification and selection of relevant evaluation criteria that are essential for the assessment. These criteria can be qualitative or quantitative, and they are often weighted according to their relative importance. Subsequently, a set of fuzzy membership functions is defined to establish the degree of membership or relevance of each criterion to the evaluation process. These membership functions often take the form of linguistic variables, enabling the inclusion of subjective human judgments in the evaluation process. Afterward, the fuzzy evaluation matrix is constructed, which represents the relationship between the evaluation criteria and the assessed object. Finally, this matrix incorporates the assigned membership degrees and weights to calculate the comprehensive evaluation result. The calculation process of the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method can be divided into six steps:

- (1)

Establishing the factor set

For this study, the issue to be examined is the public’s comprehensive evaluation of the project after the visit. Comprehensive evaluation is multifaceted, a visitor’s perspective as a participant in individual evaluation is different. Therefore, it is necessary to clarify what are the influence factors on the cultural expression of the project. In other words, what aspects of the project do visitors care about? Let us suppose there are

aspects, the factor set

is established as follows:

- (2)

Establishing the weight set

Since each influence factor affects the evaluation objectives to a different degree, each influence factor should be given a numerical value to reflect the degree to which it affects the comprehensive evaluation result. Therefore, for these

influence factors, represented by weights

, the established is as follows:

- (3)

Establishing a judgment set

A qualitative research set of judgments will be established and used to judge each of the influence factors to achieve a final comprehensive evaluation, represented by

, and there are

levels, as follows:

- (4)

Determining the membership degree

This is the key to converting qualitative to quantitative research. The study needs to translate the results of the visitors’ evaluations into judgement levels. In a fuzzy set, this is represented by the degree of membership, that is, the degree of closeness to the set evaluation level. What it reflects is the matrix relationship between

and

, represented by

:

- (5)

Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation calculation

After performing the membership evaluation determination of each influence factor, combined with the weights

, the comprehensive evaluation calculation of the evaluation target can be obtained:

In this formula, “” is the operator for multiplication.

- (6)

Determining the evaluation results

The result of the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation reflects a meaning similar to that of Step (4), which reflects the membership with evaluation levels. This result can be seen as the degree of public approval on each evaluation level. Higher values express a level at which more people are evaluating the project at that level.

3.3. Interview

Although the principles and formulas of the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method are clear above, there are still challenges in practice. The purpose of the interview is to be able to obtain data on the public’s “tastes”, which will be counted as the basis for a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation.

Firstly, Step (1) is how to build the set of influence factors. In order to address this challenge, the study will conduct an interview with 126 visitors in 1933 Old Millfun. At the exit of the project, researchers will interview visitors. The interview questions are: “what did you think impressed you about 1933 Old Millfun after your visit?” and “how do you comment on this (these) aspect(s)?” They are open questions, and in practice, visitors talk freely about how they feel after their visit. After the interviewee answers the questions, the researcher confirms the summarized categorizations by feeding them back to the interviewee. For example, if an interviewee talks about the facade of the building and the shopping experience, this would summarily and, respectively, be categorized as aesthetic and consumption. The impressions described by 126 visitors are categorized and organized to establish a set of influence factors.

Then, Step (2) is how to determine the weights of the influence factors. The aspects of cultural expression for each interviewee are different, and by counting the frequency with which these interviewees mention the influence factors, the corresponding weights can be obtained. The more frequently an aspect is mentioned, the more interviewees care about it, and therefore, the higher the weighting value will be.

Finally, it is about the membership of interviewees’ evaluations in Step (4). The study proposes to establish the judgment set as: very good , normal , and unsatisfactory . When the researcher confirms the summarized categorizations with the interviewee, the interviewee will also be asked to choose a reasonable level of judgment: very good, normal, or unsatisfactory. The number of people accumulated is the determining value of the membership of the aspect.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Influence Factors

The factor set is created based on the descriptions of the 126 interviewees. According to the statistics, the 126 descriptions can be divided into a total of 220 items, and the aspects covered by these items can be summarized into four factors: Aesthetics ; Explanation ; Specificity ; Consumption .

Aesthetics

During the interviews, 86 visitors commented on the aesthetic aspect of 1933 Old Millfun. The largest data among the four influence factors indicate that aesthetics is considered to be the most impressive in this project. Visitors can not only be interested in the industrial landscape, but also obtain good portraits and pictures in an industrial scenery setting. The word “photograph” has become a high-frequency word. As can be seen from

Figure 2,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, 1933 Old Millfun retains its original industrial landscape: heavy concrete without any unnecessary decoration; intricate open-air and semi-enclosed spaces with connecting bridges (streamlines for slaughtering); and flowering columns with a strong rhythmic arrangement and sculptural sense. Such a shocking visual experience will naturally be the main attraction of the project; this drives the aesthetic culture of the industry [

60]. However, this visual experience was not accepted by all visitors. There were four people in the interview who expressed feelings of “eeriness” and “scaredness”.

Explanation

In the interview, 30 visitors expressed a desire to know (or wish to know) the historical story behind 1933 Old Millfun. When faced with such a historical building and while enjoying a visual feast, visitors will naturally be curious about its origin and the story behind it. At this point, 1933 Old Millfun, as an important cultural heritage of the city, has a responsibility to explain and transmit its cultural significance and meaning to the public. However, the feedback from the interviewees showed that the explanatory description of 1933 Old Millfun is mixed. Some interviewees were only able to describe “that was once an important slaughterhouse in Shanghai”; there were also some visitors who desired to learn about the cultural stories, but did not find the answers after their visit; only three visitors were able to name the historical function to some of the detailed elements of the building.

Specificity

Both in terms of architectural space and historical industrial type, 1933 Old Millfun is special in China [

23]. This is mentioned by 52 interviewees, all of whom answered in the affirmative. These interviewees’ descriptions of the scarcity of the project are not only about the history of the abattoir, but also about the peculiar architectural space. The project’s past is a representation of killing, the transformation of the building has removed the machines and tools of slaughter, and what remains are complex traffic flows and unusual spaces of light and shadow.

Consumption

For 1933 Old Millfun, cultural consumption is necessary because it is nowadays a mixed function. A total of 52 interviewees commented on this aspect. The evaluation involved retail, restaurants, café, and venue rental, which essentially covered the consumption items in the project. The evaluation results show that visitors are not uniformly impressed with the experience of spending money on the programs. Mostly, visitors come without a clear purpose of spending money, and they are able to provide a fair assessment of the project’s commercial environment; there are also few visitors who come for a particular store and may present a higher rating as a result. All of these data provide true feedback on the public’s (different backgrounds and motivations) evaluations, thus setting the foundation for the authenticity and scientificity of the study.

4.2. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation is based on the factors developed above, and will evaluate whether industrial culture is accepted by the public in 1933 Old Millfun. According to the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method in

Section 3.2 and

3.3, the factor set and the evaluation set can be interlinked, where the evaluation scores of influence factors are completed based on the interview, and the matrix table can then be created, as shown in

Table 1.

According to Step (4), the fuzzy matrix can be established as follows:

The next step is the determination of the weights of each factor. As stated in Step (2), the weights can be determined by relying on how often the interviewees describe the factor. The number of interviewees who mentioned the corresponding influence factor in their descriptions is shown in

Table 2.

The level of interest by the interviewees in the different factors can be seen from the data in

Table 2. Using this as the weights, the result is shown in

Table 3.

According to the formula of the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method (Step (5)), the evaluation calculation can be presented as a combination of the matrix and the weights. The final comprehensive evaluation results can be found as follows:

In this formula, “” is the operator for multiplication.

5. Results and Discussion

Based on the evaluation process in

Section 4, multiple findings can be obtained about 1933 Old Millfun. There are four influence factors obtained during the interviews, which provide a clear understanding of the cultural expression in terms of what aspects the public wants from the project. These serve as the basis for effective upgrading suggestions for the future development of the project, in order to build on strengths and avoid weaknesses.

5.1. Aesthetics

Vision is one of the most important dimensions in the evaluation of architecture and the environment [

61]. Since industrial architecture has many differences from civil buildings, in these reused projects, users can appreciate novel architectural elements (such as their planning, spatial layout, material texture, and color palette) that reflect the high aesthetic value [

23,

60]. The architectural styles of industrial heritage buildings have become a source of inspiration for contemporary designers, architects, and artists [

62]. The raw aesthetic, exposed materials, and adaptive reuse techniques have influenced modern architectural movements such as the industrial aesthetic and loft living [

46]. The blend of old and new, the repurposing of industrial structures for contemporary function, serves as a testament to the resilience and flexibility of industrial heritage buildings and their intrinsic cultural value.

Thanks to the rapid development of smartphones and social media, people are becoming inclined to share their experiences [

63]. In terms of people’s travel experience, sharing beautiful photos is one of the main ways to achieve attention, and it is also considered a way to satisfy the need for esteem [

23]. This aspect is extremely well represented in 1933 Old Millfun. The project has a huge aesthetic appeal and the visitors’ comments are overwhelmingly positive (very good: 95.35), except for a few people; also, the aesthetic aspect has the largest weighting of 39.09%, indicating that the aesthetics of the project has become its main attraction.

5.2. Explanation

Historical context is the main component of industrial culture, which distinguishes the reused industrial heritage from other types of buildings [

42,

64,

65,

66,

67]. The legacy of industrial heritage is evidence of history [

68]. It can not only reflect the manufacturing activities of a specific period and region, but also tell the story of the historical context of the society at that time. People visit the building to experience history and gain knowledge of historical industrial culture. Some of the parents would like to use such places for their children’s history education. Contrary to the textual descriptions available, building users face challenges when trying to grasp the significance of the preserved industrial heritage without proper guidance or explanation. Education and the imparting of historical industrial culture heavily rely on the interpretations provided by these specialists [

23,

36,

69]. Additionally, it becomes essential to employ various tools such as panels or more dynamic and immersive methods employed by museums to describe and present each exhibit in great detail. Through these means, a richer and more engaging experience can be achieved, enabling building users to develop a deeper understanding and appreciation for the preserved industrial heritage.

A building that can be called an industrial heritage should be of significant historical, technological, social, architectural, or scientific value [

22,

70]. The 1933 Old Millfun deservedly shows its historical story to visitors, not hidden as an archive on the bottom shelf of the shelves. However, the fact is that a few people (the weight: 13.64%) were impressed by the cultural expression of the project. The very small number of explanatory signs in the project made them easy for people to overlook.

5.3. Specificity

Unique and captivating cultural experiences play a pivotal role in promoting and sustaining the growth of cultural tourism focused on the revitalization of industrial heritage sites [

71]. The allure of such a cultural experience lies in its ability to captivate the imagination and curiosity of tourists, stimulating their desire to explore and discover [

72]. Similar industrial culture can reduce people’s desire for cultural exploration and weaken the cultural influence of a reused heritage project [

30]. In a way, an industrial heritage project should stand out for its industrial cultural value. The specificity of industrial heritage can help to raise awareness and thus attract a wider range of people; that is, the scope of the project’s cultural attractiveness could be affected by the scope of its cultural specificity. For example, if the history and architectural form of the project is the only one in China, it will attract people from all over China; if it is the only one in the world, then it will attract people from all over the world.

The 1933 Old Millfun can be considered a success in terms of cultural specificity. The industrial heritage of such a slaughterhouse is indeed one of the very few that exists in a country like China that shuns death. All visitors who mention the project’s past will be amazed by it. The architecture completely preserves the space that was once designed for manufacturing, and showcases the experience of industrial aesthetics.

5.4. Consumption

Cultural consumption is the willingness to consume mainly for the purpose of industrial cultural experiences [

73], which includes a collection of industrial culture souvenirs and an industrial environment experience. One of the key attractions of cultural consumption in a reused industrial heritage site is the sense of nostalgia and historical charm it invokes. Indeed, a reused industrial heritage can create a captivating ambiance that cannot be replicated elsewhere. Economic income can sustain most projects’ development over time [

74]. The reuse of industrial heritage in China is dominated by public space and creative industries, which has become one of the main places of consumption for the public [

23]. These functions allow the users to realize their spiritual needs such as pleasure and relaxation in the consumption of spaces with a unique industrial cultural atmosphere.

For 1933 Old Millfun, combined with the impressive visual space, the consumer experience in the project should be enjoyed by visitors; however, from the results, visitors did not have a good experience with the retail, and even described it as “disappointing”. Interviewees suggested that there should be more stores related to the heritage theme. They were more interested in having souvenir stores, 1930s nostalgia-style stores, and meat-related restaurants.

5.5. The Results of the Comprehensive Evaluation

Based on

Section 4.2, the calculated data results have provided us with valuable insights into the evaluation set for the project. The results indicate: very good, 70.45; normal, 13.64; unsatisfactory, 15.91. These resultant scores are considered as a comprehensive rating of interviewees’ comments. The evaluation level with the highest score can be seen as the most people agreeing at this level. This will be the final overall evaluation of the project, which is the principle of maximum membership [

29,

57]. For the cultural expression in 1933 Old Millfun, the maximum score (70.45) is in the “very good” level. it can be concluded that the project is performing exceptionally well in general.

The Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method is particularly effective for making horizontal comparisons between various projects. The reason behind this lies in the fact that each project possesses its unique cultural attraction. As a result, designers naturally tend to emphasize different aspects of cultural expression within each project, making it challenging to compare them on an equal level. However, the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method has been specifically designed to accommodate these inherent differences and successfully weigh them. This unique approach allows for a fair and unbiased comparison of the projects’ overall success or failure in terms of cultural acceptance.