Abstract

Irrationality is a strong phenomenon in consumer behavior that significantly impacts final purchase decisions. Through holistic approaches, companies have become more oriented towards emotional experiences. This study investigates the emotional impact of Dove brand advertising appeals on the frequency and intensity of emotions experienced by Slovak consumers. A theoretical framework was created for the conceptual development of emotional appeals in advertising and their impact on irrational purchasing behavior. An online questionnaire was conducted using the scale of subjective emotional habitual well-being (“SEHP”) of the psychodiagnostic tool on a sample of 417 Slovak consumers. The results show that (1) advertising with emotional appeal has different effects on consumers’ purchasing behavior depending on their age, (2) advertising with emotional appeal affects consumers more negatively than positively, and (3) the use of emotional appeal in the advertising space creates an emotional connection with the brand. Our study shows that the current trends in the influence of emotional appeal can promote impulsive and irrational buying behaviors. Thus, consumers become part of the brand, creating an emotional connection between them. This connection can result in positive purchase decisions. Creating emotional appeal in cosmetic products also has social significance in building self-confidence, status, and beauty.

1. Introduction

The market environment offers new opportunities, and the current dynamics of applying traditional communication policy tools are differentiating. Businesses strive to ensure effective strategic management by respecting current trends. They use nontraditional procedures and tools that positively influence consumer shopping behavior and decision-making. Due to changes in consumer shopping behavior trends, focusing more on emotional rather than rational decision-making processes is necessary.

The decision-making process in this study follows the approach proposed by Arslanagic-Kalaidzic et al., who investigated a deliberate selection of a specific problem-solving method within defined circumstances [1]. According to the authors, it is important that decision making is aimed at fulfilling a predefined goal. From a marketing perspective, leading the decision-making process towards the customer’s final product selection is possible. This means that among the product alternatives, customers choose the one that most effectively meets their needs and requirements. According to Clore, rational decisions are made by maximizing utility and minimizing costs, forming the basis of neoclassical economics [2]. Thus, it can be stated that from the shopping behavior point of view, people are more interested in the logic and consistency of their own beliefs and actions.

Consumer behavior is a psychological phenomenon of cognitive dissonance [3]. Research by Lahtinen et al. found that when individuals engage in actions that contradict their beliefs, it gives rise to tensions and emotions [4]. Subsequently, this can motivate them to start an emotional and intuitive decision-making process that can significantly impact their purchasing behavior and decision making. This integrates the cognitive and affective factors involved in emotional decision-making processes. The professional literature indicates that engaging such factors and processes can activate irrational purchase decisions. This is an important part of the evolutionary development of consumer behavior in the market environment. Thomaz emphasized the importance of emotions, the effect of which can be verified from a company’s perspective through the practical application of communication tools using various emotional appeals [5]. Their influence can also be perceived from the customer’s point of view, who begins to manifest various feelings associated with his purchasing behavior and decision making. Sanchez and Franco stated that every behavior is related to emotions because it is motivated by an expected effect [6]. From the author’s perspective, mental stimuli are involved in predicting probabilistic outcomes. Emotional decision-making processes are manifested when maximizing decisions, and activating customers’ irrational behavior in the market environment. Clore and Huntsinger present a different perspective on this matter, suggesting that even though general thinking may be unconscious, automatic, emotional, and heuristic, individuals can still reach rational and justifiable conclusions [7]. Concerning purchasing behavior, they found that rational decision-making processes only occur after emotional decision-making processes have been influenced.

Based on the above, it can be stated that consumers’ shopping behavior involves both rational and emotional decision-making processes. However, these processes differ from the assumptions made in traditional economic theory. Therefore, emotional actions have a major impact on consumers’ shopping behaviors and decision making. Simultaneously, the use of subconscious stimuli in advertising and marketing practices is growing. According to Rajan, several factors can influence consumer shopping behavior [8]. These are mainly the influence of marketing communication, technological factors, social networks, emotional influence, and neuromarketing elements. Lin et al. also highlight the importance of emotional appeal, arguing that comparative characteristics are important in the decision-making process but that the consumer makes a decision based on an emotional response. The aim should be to respect the traditional marketing tools that present product features and benefits [9]. However, the current trend reflects that advertising and marketing activities should be aimed at strengthening the brand image. Lin et al. argue that such reinforcement reflects the emotional connection that must occur early in the initial campaign [9]. The sooner such an emotional connection is established, the more effective and readily the consumers will make a decision. The behavioral aspect can thus be considered key and justified in the current marketing environment for influencing consumers’ shopping behavior, strengthening competitive position, and strengthening brand value.

The aim of our study is to confirm the emotional impact of advertising appeals on consumers. The research will confirm the fact that there are currently significant differences in the perception of the emotional campaign between the younger and older generations. There are also differences in the irrationality of purchasing behavior. From the above, the objectives of the research were formulated as follows: (1) Can brands create emotional connections with customers? (2) Does advertising’s emotional appeal affect purchasing behavior and decision making? (3) How does advertising with emotional appeal affect consumer behavior?

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Effect of Emotional Advertising Appeals on Customer Purchasing Behavior

Emotions are important for irrational shopping behavior. Gebhardt et al. defined emotions from a psychological point of view as behavioral, physiological and cognitive reactions of a person to a situation [10]. These reactions are considered a key part of analyzing the impact of emotional appeal on consumers in the advertising space. The correct use of emotions in advertising can be considered one of the principles of irrational shopping behavior.

In connection with the advertising campaign, it is important to correctly define the basic types of emotions. According to Wang et al., the basic types of emotions that can be assessed in the studied context are anger, sadness, joy, surprise, disgust, and fear; however, the advertising space uses various categorized emotions, also referred to as emotional appeals [11]. Lindauer et al. (2020) categorize marketing emotional appeals as joy, sinfulness, stories, fear, and eroticism, thereby deviating from Ekman’s categorization [12]. The only consistency observed between the two categorizations was for joy and fear. This study will examine in detail the advertising implications of emotional categorization, specifically focusing on the emotional model of Lindauer et al. [12].

Depending on their effectiveness and impact, emotional appeal in advertising can be implemented through different theoretical models. These models include the implicit model, where emotions serve as the main features of the product; an explicit model that uses emotions and various stimuli to influence consumer attitudes and purchasing decisions; and the association model, where emotions are evoked through social motives and cues and indirectly associated with brands and products [13]. Concerning behavioral changes, it can be argued that emotions also influence purchasing behavior and decision making. Kranzbühler et al. argued that emotions are evaluative patterns that influence consumer behavior [14]. They can evoke positive reactions such as humor, joy, or surprise. Negative emotional appeals are emerging in addition to positive emotional appeals. Rathore and Ilavarasan highlight the current trend in advertising spaces of evoking negative emotions; negative emotions in the advertising space can cause sadness or disgust in consumers, create nostalgic memories associated with a certain life event, and incite anger or fear [15].

If a negative emotional appeal is incorrectly applied to the advertising space, it can impact the effectiveness of the overall marketing strategy. However, a business can intentionally create advertising content with negative emotional appeal. In such cases, it is important to use this emotion correctly in relation to the promoted product [13,15]. Advertising that employs diverse emotional appeals has gained popularity and exerts influence on the ultimate decision-making processes of consumers [13,16].

Advertising can evoke emotion, but the challenge lies in directing those emotions toward purchasing the promoted product. This means that the target segment may be emotionally activated but not to the extent it will buy. Another problem based on the author’s model is correctly targeting emotions and using appropriate psychographic factors for target segments. Working with emotions and applying them correctly to advertising spaces can be considered a demanding process for companies, regardless of their target audience. According to Scarantino et al., traditional economic models of consumer behavior assume a hierarchy of effects in which an emotional evaluation of attitudes toward a brand or product follows cognitive activity [16]. According to this model, the consumer is primarily influenced by the product or the price, and the emotional evaluation follows only after the purchase of the product. The model does not assume irrational buying behavior. The authors identified the extent to which emotions drove customer consumption. The emotion-driven choice model of Scarantino et al. outlines a specific consumption situation. They divided the model into three phases: motivation, preference formation, and choice justification [16]. They found that, depending on age, there are differences in the motivation to buy, formation of preferences, and justification of the choice to buy a given product.

The purchasing behavior of generational lines can be perceived differently. Each generation behaves differently in the market environment. According to Azemi et al., emotional perception is stronger in Generation Z than in Generations X and Y [17]. Their model defined the elements through which the final decision was stimulated, covering emotional perception, loyalty, purchase speed, and rational beliefs. According to Raza et al., it is necessary to be cognizant of greater loyalty to the brand. Generation X tends to exhibit rationality in their purchasing behavior, whereas Generation Y is heavily influenced by social media and influencers. The latter group experiences a significant impact, with influencers delivering messages that are 80% stronger and more memorable during the purchase decision-making process. Social networks generate much stronger impulses for purchasing behavior than classic television advertising [18]. Despite the effective nature of emotional appeals, they need to be correctly used and appropriately targeted to the relevant generation.

In connection with the impact of emotional appeal in advertising on purchasing behavior, the following hypotheses were established:

Hypothesis 1.

The use of emotional appeals in advertising significantly influences purchasing behavior across different age groups, with older individuals being more responsive to emotional appeals compared to younger individuals.

2.2. The Emotional Connection of the Customer with the Brand through Advertising

The primary goal of an emotional advertising campaign is to create and perceive the intensity of the connection between the product, the brand, and the customer in the form of an emotional response. A campaign that creates an intense connection between a customer and a brand or product should adequately generate reactions that can support the customer-business relationship. A strong correlation can be observed between television advertising and its influence on individuals in different age groups. Cartwright argued that current advertising campaigns are promoted on social networks, television, radio, and other media. In his study, the author defined the differences in the perception of advertising campaigns for individual media [19].

Depending on the use of different types of media, campaigns can stimulate purchasing behavior and decision making in different ways. There are several emotional expressions that businesses try to promote in their advertisements in an attempt to create an emotional connection. Attitudes and perceptions of advertisements differ between different age groups of consumers [19]. In Cartwright’s research, the differences in the perception of the emotional impact of advertising between men and women are significant. Based on this, the following hypothesis was established:

Hypothesis 2a.

The influence of emotional appeals in advertising on consumer behavior is subject to gender-based variations, with females exhibiting a greater susceptibility to emotional appeals as compared to males.

Since 1980, considerable focus has been placed on studying emotions in advertising and assessing age-related variations in positive and negative attitudes. Barve et al. showed that adolescents are acutely aware of the effects of emotional appeal, which can also influence their resulting behavior in the market environment; however, they focused primarily on the negative and positive effects of television advertising on teenagers [20]. Social networks strongly influence teenagers. According to Cartwright et al., social networks attempt to promote products through influencers to encourage purchasing behavior and strengthen the involvement of the target segment [19]. Berne-Manero and Marzo-Navarro found that emotions can also be a key factor in increasing adolescent engagement or changing behavior [21]. Generally, emotions in an advertising space can impact interactions between the customer and the company.

Research conducted by Zollo et al. showed that cognitive processes and personal and social integration mediate the relationship between the marketing impact of social media ads and consumer brand awareness. They argued that emotional brand experiences could also strengthen customer loyalty and build brand equity [22]. In this context, the following hypothesis was defined:

Hypothesis 2b.

The relationship between mood (positive or negative) and the perception of an emotional advertising campaign varies across different age categories. Null hypothesis (H0): there is no significant interaction effect between mood (positive or negative) and age category on the perception of an emotional advertising campaign. Alternative hypothesis (Ha): there is a significant interaction effect between mood (positive or negative) and age category on the perception of an emotional advertising campaign.

Originality and appeal of advertisements can lead to better customer feedback. According to Holbrook and O’Shaughnessy, if emotions are adequately leveraged in advertising, they can lead to a more positive attitude towards advertising and branding [23]. O’Shaughnessy also highlighted the utilization of emotions in advertising, proposing a model that elucidates the emotional dimension’s role in the final decision-making process [24]. In this model, they defined the basic dimensions that can be part of the advertising message and can thus elicit a certain emotion in the consumer in the final decision. Activation and kinship are associations that the customer creates while watching an advertisement (e.g., close and loving relationships with others, isolation factor). The Hedonian tone represents the attainment of inner harmony and relaxation. The last dimension pointed out by the author is competency. According to O’Shaughnessy individual dimensions are associated with values and preferred lifestyles [24]. If they appear in advertising, conditioning mechanisms evoke mild or severe emotions. Subsequently, the evaluation is conducted through identification, conditioning, or infection. Conditioning occurs in connection with the formation of associations that stimulate conditioned responses.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Measuring Buyer Behavior Techniques and Methods

Understanding buyer behavior is essential for developing successful marketing strategies and catering to the requirements and preferences of the target audience. This article intends to provide an overview of the diverse techniques and methods used to measure consumer behavior. Utilizing these methodologies, marketers can obtain valuable insights into the decision-making processes, motivations, and purchasing patterns of consumers. This information allows businesses to tailor their marketing strategies and increase customer satisfaction.

- I.

- Surveys and questionnaires

Utilizing surveys and questionnaires is a common method for measuring consumer behavior. Through face-to-face interviews, telephone surveys, or online forms, these tools collect information directly from consumers using structured questionnaires [25]. Researchers are able to collect information about consumer preferences, purchasing habits, brand perceptions, and demographic characteristics through the use of surveys. The quantitative insights provided by the analysis of survey responses pertain to consumer behavior.

- II.

- Observation and field experiments

Observation and field experiments are utilized to examine consumer behavior in natural settings [26]. Researchers actively observe and record consumer actions and interactions in retail environments, online platforms, or other relevant contexts. In contrast, field experiments involve manipulating specific variables and measuring their effect on consumer behavior. This method provides valuable insight into the decision-making processes of consumers in real time.

- III.

- Focus groups and in-depth interviews

Focus groups and in-depth interviews entail direct interactions with a small group of consumers in order to collect qualitative information about their behavior. In contrast to focus groups, in-depth interviews are one-on-one conversations with participants [25]. These methods enable researchers to delve deeper into the consumer’s purchasing-related motivations, attitudes, and emotions.

- IV.

- Social media research

In the digital era, social media has become a plethora of information for measuring consumer behavior. Tracking and analyzing consumer conversations, comments, and sentiments on social media platforms [27]. This method provides insights into consumer opinions, brand perceptions, and product preferences, enabling businesses to comprehend and respond in real time to customer requirements.

- V.

- Neuromarketing Techniques

Neuromarketing integrates neuroscience and marketing to assess the subconscious buyer behavior. To comprehend consumer responses to marketing stimuli, techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and eye-tracking are utilized [28]. These methods provide marketers with insights into consumer emotions, attention levels, and preferences, allowing them to devise more effective marketing strategies.

For businesses to obtain a comprehensive comprehension of their target market, the measurement of buyer behavior is crucial. This summary has outlined a variety of techniques and methods for measuring consumer behavior, including surveys, observation, focus groups, social media analysis, and neuromarketing techniques. By employing these methodologies, businesses can gain valuable insights into consumer decision making, preferences, and motivations. This knowledge enables marketers to create customized strategies, increase customer satisfaction, and ultimately drive business success.

3.2. Emotional, Habitual, and Subjective Well-Being Scales

Emotional well-being, habitual well-being, and subjective well-being are crucial constructs in the field of psychology, and they are frequently measured with specialized scales. These instruments enable researchers to measure and comprehend various aspects of well-being, thereby providing valuable insights into the psychological and emotional states of individuals. This summary focuses on some commonly employed instruments for assessing emotional, habitual, and subjective well-being.

- 1.

- Emotional well-being scales:

- a.

- Positive and Negative Affect Schedule:The PANAS is an extensively utilized self-report scale that measures positive and negative affect, capturing a person’s emotional spectrum. It consists of two subscales: positive affect (such as happiness and enthusiasm) and negative affect (such as sorrow and anger). Respondents indicate the degree to which they have experienced each emotion during a given time period [29].

- b.

- Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale:The CES-D is a self-report scale designed primarily to measure depressive symptoms. It measures the frequency and severity of symptoms associated with melancholy, such as sadness, appetite loss, and trouble sleeping. It has been utilized extensively in both clinical and research contexts to assess emotional well-being [30].

- 2.

- Habitual well-being scales:

- a.

- Satisfaction With Life Scale:The SWLS is a self-report scale that measures an individual’s cognitive evaluation of life satisfaction. It consists of five items that measure overall satisfaction with various aspects of life, such as family, work, and leisure. On a Likert scale, respondents rate their agreement with each item, providing a measure of habitual well-being [31].

- b.

- Flourishing Scale:The FS is a self-report scale that evaluates the psychological and social well-being of an individual. It evaluates aspects such as life purpose, positive relationships, self-esteem, and activity participation. On a Likert scale, respondents indicate their level of agreement with each of the eight items [32].

- 3.

- Subjective well-being scales:

- a.

- Subjective Happiness Scale:The SHS is a brief self-report scale that measures the subjective contentment of an individual. It consists of four items that emphasize global contentment and life fulfillment. Respondents indicate their level of agreement with each statement, providing a subjective evaluation of their well-being [33].

- b.

- World Health Organization’s five well-being index:The WHO-5 is a self-report measure of subjective well-being. It consists of five items measuring positive disposition, vitality, and general life interest. On a Likert scale, respondents indicate their level of agreement with each item, yielding a subjective well-being score [34].

- c.

- Emotional habitual subjective well-being scale or SEHP scale:This scale was introduced by Dzuka and Dalbert in their research called “Elaboration and Verification of Emotional, Habitual, Subjective Well-being Scales”. The article focuses on the development and validation of scales to measure emotional, habitual, and subjective well-being (SEHP) in the Slovak population. The study aims to provide a comprehensive tool for assessing well-being and sheds light on the validity of these scales. The researchers contribute to a clear and concise description of the scale items and their theoretical underpinnings. Furthermore, the study addresses the limitations of previous well-being scales by incorporating dimensions of emotional, habitual, and subjective well-being, thus capturing a more comprehensive understanding of individuals’ overall well-being. This multidimensional approach contributes to the richness and validity of the SEHP scales [35].

These scales provide researchers and practitioners with valuable instruments for assessing emotional, habitual, and subjective well-being, enabling them to obtain insights into various dimensions of well-being. In empirical studies, researchers frequently employ these instruments to measure well-being and investigate its associations with other psychological and social factors.

3.3. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

A questionnaire divided into a non-standardized and a standardized part was used for data collection. In the non-standardized part, it was investigated whether consumers notice the use of emotions in advertising space. A 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 5 for “not at all—strongly influenced”) was used to determine the impact of emotionally appealing advertising on consumer purchasing behavior. In the non-standardized part, it was determined whether an emotionally appealing advertisement creates habitual purchasing behavior.

In the second part of the questionnaire, the psychodiagnostic tool of the standardized scale of emotional, habitual subjective well-being (SEHP) was used. The SEHP scale was used to investigate consumers’ emotional states after viewing Dove’s #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign. In the theoretical part of the study, it was found that influencing factors have an 80% higher incidence of emotional reactions than television advertising among young individuals. Dove’s #DetoxYourFeed ad campaign was chosen to see if it had a different effect depending on the generational groups and gender of the respondents. The aim of this research was also to find out if this advertising campaign effectively supports the buying behavior of women.

Descriptive words that express emotions or bodily sensations were used to measure the emotional component of subjective well-being. The term “item” was used to describe descriptive words. During the measurement, the intensity of their occurrence and the frequency of experienced emotional moods after viewing the #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign were determined. The frequency of respondents’ positive and negative moods was monitored using a standardized methodology [35]. Positive mood was defined by the following items: joy, happiness, enjoyment, and physical freshness. Negative mood was defined as shame, anger, guilt, fear, pain, or sadness. The SEHP scale is presented in Table 1. Respondents reported the frequency and intensity of the items they experienced after viewing the advertising campaign.

Table 1.

The subjective emotional habitual well-being (SEHP) scale.

Respondents indicated the strength of a given emotional experience for each item on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6. After highlighting the emotional experience, the respondents answered the question of how strongly the advertisement influenced their purchasing behavior. The questionnaire was distributed online through the Survio application (a platform for collecting data from questionnaires) on Facebook and Instagram.

3.4. Description of Sample Statistics

The statistical sample size was calculated at 384 respondents. In total, 450 questionnaires were returned. Of the total questionnaires, 422 were completed, and 5 were excluded due to incomplete data. The return rate of the questionnaire was 93.77%. Based on the relevant statistical sample results, 417 acceptable questionnaires were included for analysis in the survey.

The characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 2. Although the research subject was an advertising campaign for a cosmetic brand, the percentage distribution of men and women was comparable (men: 44%; women: 56%). The age range of the respondents was defined according to generational lines: Baby Boomers, Generation X, Generation Y, and Generation Z [36]. The study involved a total of 249 participants belonging to Generation Z (18–25 years old), accounting for 59.71% of the total sample. Additionally, 92 participants from Generation Y (26–41 years old) were included, making up 22.06% of the total sample. Generation X (42–56 years old) was represented by 56 participants, comprising 13.43% of the total sample. Lastly, 20 participants from the Baby Boomer generation (57–75 years old) participated, accounting for 4.80% of the total sample.

Table 2.

Basic respondent characteristics.

3.5. Reliability and Validity Analyses

SPSS Statistics software (version 27, IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to verify the validity of the hypotheses. In the non-standardized part of the research, mathematical statistics were used to verify dependence. These results were appropriately validated for the relevant aspects of the study. Spearman chi-square was used to test independence between variables. A significance level of 0.05 was utilized for all statistical tests. To ensure statistical robustness, the condition was set that 80% of theoretical numbers had values greater than five, and each value was non-zero (minimum of 1).

Cramer’s V mathematical-statistical method was employed for variables with statistically significant differences. The results were interpreted as follows: a value of 0.1 indicated a weak contingency, 0.3 represented a moderate contingency, and 0.5 indicated a strong contingency [37]. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of the data, as there were more than 50 measurements in each category. The data did not follow a normal distribution (the p-value was less than the significance level in all dispositions); hence, ANOVA for two independent sets was used to test the assumption of equality of median values in each set of the explanatory variable.

The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to verify whether men and women had the same emotional response. This nonparametric test is robust when the assumption of data normality is not met. The statistical significance of Hypothesis H2a was tested with an α level of 0.100, chosen based on previous research indicating significant dependence at this level [38]. According to the authors, the internal consistency of both scales was significantly balanced during repeated administration. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.827 for the four positive mood items; the positive mood scale exhibited a reliability of 0.748 based on Cronbach’s coefficient. In negative mood conditions, the coefficient reached 0.830 [38].

Because the age categories were divided into several intervals (there was an assumption of a larger number of independent samples), we chose a one-factor ANOVA Kruskal–Wallis test (5 < n < 30) to verify H2b. We assumed the perceptions of positive and negative moods for individual age categories in the #DetoxYourFeed commercial advertising campaign and used this test to compare the differences in the median values in several categories. The significance level α was set at 0.100 for the statistical evaluation of H2b.

4. Results and Hypothesis Testing

4.1. Verification of the Validity of the Hypothesis from the Non-Standardized Part of the Questionnaire

Hypothesis H1 was created from the non-standardized part of the questionnaire, which was defined in the theoretical part of our study. Hypothesis H1 examined the significance between age category and the effect of emotional appeal advertising on purchasing behavior. The data used, and their alternative names are described in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Description of data used in H1 hypothesis testing.

Spearman’s correlation was used to measure association that assesses the monotonic relationship between variables. It ranks the data and calculates the correlation based on the ranks. Spearman’s ρ is suitable when assuming that the relationship between variables is monotonic, meaning that the variables tend to increase or decrease together, but not necessarily linearly. The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients.

Under the null hypothesis of no correlation, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient would be expected to be zero. However, the calculated rho value of −0.18, and −0.45 indicates a moderate negative correlation between Q2 and Age and Q1, respectively. Calculated p-values show that there is a statistically significant correlation (negative and positive) between the pairs of variables being analyzed.

Spearman chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the statistical significance of the relationship between age and the effect of emotional appeal advertising on consumer purchasing behavior. The relationship between these variables was significant: H1a: X2 (16, N = 417) = 33.951a, p = 0.002. We used an alpha level of 0.05. There was a statistically significant difference between the age variable and the effect of emotional appeal advertising on purchasing behavior. Advertising with emotional appeal significantly affected the age groups. Cramer’s V test was used to detect statistically significant differences between the groups. The strengths of the dependence between the investigated variables are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The result of the verification of the strength of the dependence of hypothesis H1a Cramer’s V.

A weak dependence was found between the investigated variables of age and the effect of advertising with emotional appeal on purchasing behavior [37]. Considering the statistical significance of the studied variables (age and the impact of advertising with emotional appeal), we identified how advertising with emotional appeal impacted individual age categories (Table 4).

According to the data in Table 4, it is possible to conclude that advertising that includes emotional appeal has a probability of greater impact on respondents aged from 18 to 25 years and will have less impact on older groups of population. According to the results, the older age categories were no longer impacted. However, advertisements with emotional appeal can encourage irrational shopping behavior, which is reflected in the final purchasing decision.

4.2. Verification of the Validity of Hypotheses from the Standardized Part of the Questionnaire

4.2.1. Verification of Data Normality

To verify the validity of the other hypotheses and determine whether there is an emotional connection between the customer and the brand, the normality of the data was verified in the standardized part of the research. In the standardized part of the research (SEHP scale of subjective emotional habitual well-being), the normality of the data was verified before the test was performed. This assessment was carried out separately for both men’s and women’s positive and negative moods. Table 6 presents the results of data normality verification.

Table 6.

Verification of data normality.

Because the data did not follow a normal distribution, the validity of Hypotheses H2a and H2b was verified using ANOVA for two independent sets.

4.2.2. Statistical Verification of the Validity of Hypotheses H2a and H2b

To test Hypothesis H2a, the Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess the significance of gender in relation to negative mood after viewing the ad. For Hypothesis H2b, the significance of age in relation to positive and negative moods after exposure to the #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign was investigated. Both one-factor ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to confirm Hypothesis H2b.

H2a

The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to evaluate the frequency of positive and negative moods in men and women. The results indicated that [frequency of negative mood] was significantly greater than [frequency of positive mood], z = [−2.626], p = [0.009].

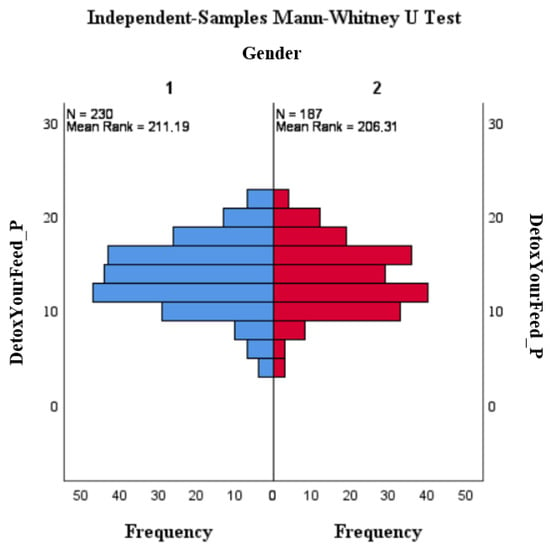

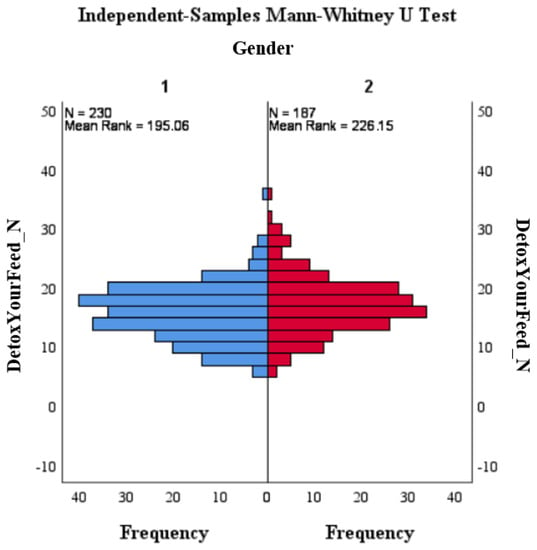

The Mann–Whitney U test provided insights into the frequency distribution of point values. These were derived from the summation of positive and negative emotions experienced by the respondents after viewing the advertising spot for #DetoxYourFeed. The assigned values for experiencing these emotions ranged from 1 to 6. Figure 1 and Figure 2 display the frequencies of these values categorized by sex.

Figure 1.

Frequency of point values of positive distribution by gender.

Figure 2.

Frequency of point values of negative distribution by gender.

Figure 1 displays the frequency distribution of positive moods, with women represented in blue and men in red. The sum of positive emotions reached 12 for both men and women. Figure 2 shows the frequency distribution of negative moods, with women having a frequency of 19 and men having a frequency of 18. This indicates stronger negative emotions while watching the #DetoxYourFeed commercial. The results shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 support the results of the Mann–Whitney U-test, which demonstrated a correlation between gender and the occurrence of negative emotions.

H2b

A one-factor ANOVA Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate the perception of positive and negative moods for individual age groups while watching the #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign. The test results are shown in Table 7, which showcases the division of results based on the perception of positive and negative moods induced by the #DetoxYourFeed commercial campaign.

Table 7.

Kruskal–Wallis Test result.

The test results indicate that the perception of positive and negative moods following the viewing of the #DetoxYourFeed commercial is influenced by age categories. This means that the #DetoxYourFeed campaign induces a differentiated experience of positive and negative emotions depending on the generational range.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Perception of the Customer’s Emotional Connection with the Brand

Advertising campaigns with emotional appeal can be perceived as a trend by which companies want to stimulate final purchasing decisions. Casais and Pereira perceive emotional advertising appeals as an important part of modern marketing practices [39]. Based on the perception of current marketing trends, it can be argued that the basic goal of advertising is to link a product with a specific emotion. They argued that only positive emotions should be significant in this connection. Our research aimed to investigate the significance and perception of positive and negative emotions in the context of purchasing decisions; hence, we disagree with their position [39]. Zhao et al. also examined the importance of emotions in their research. Their study involved 20 university graduates observing 12 different products and services to verify the importance of emotions in relation to final purchasing decisions. Products with high emotional values were found to affect final purchasing decisions positively. Ultimately, these products shape customers’ shopping behavior in a market environment. The authors also highlighted the importance of perceiving emotions in relation to customers’ shopping behavior [40].

The present study confirms that the impact of emotional advertising appeal depends on the population’s age structure. As shown in Table 4, we confirmed that advertising with emotional appeal had the most significant impact on Generation Z (consumers aged 18–25 years). Young people are exposed to various advertising campaigns that can support purchasing behavior and various social perceptions (self-confidence, self-esteem, beauty, etc.). Marketers can thus effectively adapt communication campaigns and correctly apply emotional appeals according to respondents’ age. Lim et al. emphasize the significance of comprehending buying behavior, which is deemed a primary concern for business managers. However, the authors also highlight that various other factors, such as product quality, media advertising, product value to customers, and product ethics, influence purchasing behavior [41].

5.2. The #DetoxYourFeed Campaign and Its Emotional Connection with the Customer

In the second part of the study, a subjective emotional scale was used to assess the intensity and frequency of emotional states after viewing the #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign. Through this research, we relied on the relevant part of the influence of emotional appeal in the advertising space and on creating an emotional connection between the customer and the brand.

We are witnessing a period in marketing history that is very sensitive to various topics. The significant influence of social networks not only promotes shopping behavior but also significantly impacts the self-confidence and self-esteem of young people. Advertising emotional appeals that try to reach different age groups in different ways are also emerging.

In 2004, the cosmetics brand Dove launched a project on self-esteem and self-confidence. In 2022, it modified its commercial campaign and introduced the #DetoxYourFeed campaign into the advertising space. According to internal research conducted by the Dove Self-Esteem Project, young people spend an increasing amount of time on social networks. Two of the three respondents spent more than an hour a day on social media, which is more than they spent with their friends. Another interesting result was that one in two girls said that beauty content was idealized on social media. According to these authors, such content leads to low self-confidence and self-esteem [42].

The #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign aimed to expose insidious toxic beauty advice on social networks. The campaign’s purpose was to have a significant emotional impact on social motives and topics that are currently very sensitive. It also included advertising emotional appeals and was divided into several parts. The first part of the advertising campaign involved creating a series of educational films, content, and partnerships. The campaign encouraged conversations between parents and their children regarding toxic advice on social media. The campaign film highlights dangerous topics such as “fitspo” and “thinspo”, and the promotion of optional cosmetic procedures among young girls. In the second part of the advertising campaign, the brand broadcasts short TV spots that promote toxic advice on social networks. The #DetoxYourFeed is a global marketing campaign aiming to create awareness of toxic advertising content in as many young people and their parents as possible.

The campaign met all prerequisites and characteristics of the associated model for emotional shopping behavior. According to Carrus et al., the purpose of this model is to experience emotions based on certain stimuli that are only peripherally connected to a product or brand [13]. The stimuli in our research were global social problems the advertising campaign tried to highlight. The #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign meets all the essential characteristics of an associative model that detects positive and negative emotional distributions that arise as a reaction to the observed campaign. The negative distribution of responses was found to depend on gender (see Figure 2); women perceived this advertisement more negatively than men did. The stated result is that a plausible goal of the campaign is to focus more on women than on men [13].

In connection with the #DetoxYourFeed advertisement, the respondents’ emotional states (both positive and negative) were investigated in correlation with their age. It was found that the advertising campaign induced different experiences of positive and negative emotions depending on age. Notably, a significant influence of positive mood was observed in the 18–25 age group (Generation Z). The results showed that this generation encounters similar information on social networks and is, thus, readily influenced by them. Although the advertisement campaign tried to promote an emotional appeal of fear and anger in Gen Z, it evoked more positive than negative moods. This may mean that social networks partly influence this generation and that they are already aware of the toxic advice. Conversely, the other age groups (26–75 years old) experienced a more negative impact from this advertising campaign, primarily evoking emotions of fear and anger [42,43].

Comparing the campaign to the associative model, we can say that the #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign does not emphasize the product or brand in the central part [13]. The campaign emphasizes a social motive that creates differentiated emotions among respondents. Our research confirmed through a psychodiagnostic tool that, depending on gender, negative emotions are experienced more intensively after watching an advertising spot. According to Fardi advertising does not directly promote negative emotions. The campaign’s goal is to create a feeling of creating a better parent–child relationship and to support self-confidence and self-esteem [44].

By confirming the results of the research and finding that the respondents experienced a mix of positive and negative emotions after watching the ad, we can say that the ad evoked ambivalent emotions. According to Levirni, emotions are subjective reactions to a given situation [45]. Our results also showed that the #DetoxYourFeed advertising campaign evoked different reactions in respondents regarding emotional appeal, fear, and anger. This study focused on determining the dominance of specific emotions within positive and negative emotional moods after watching an advertising spot. Among the positive emotions, the respondents experienced happiness the most. Among the negative emotional states, the dominant emotions were sadness and fear.

Although the emotional advertising campaign does not promote the product as the center of attention, it tries to create a strong emotional connection between the customer and the brand [40]. Such a connection can also support irrational purchasing behavior. Since an emotional connection can make the customer perceive more positively, it can also support future irrational (impulsive) purchasing behavior [46,47]. In addition to irrationality, such a link can support the long-term sustainability of purchasing behavior.

6. Conclusions

The use of emotional advertising appeals in the marketing communication of various brands is a current trend and is considered an essential part of modern marketing practices. Consumers are exposed to various advertising campaigns that can support purchasing behavior and social perception. Research has shown that the impact of emotional advertising depends on the age structure of the population. It was confirmed that advertising with emotional appeal had a significant impact on consumers who belong to Generation Z (young people aged 18–25). In this context, it is important to take into account generational groups when creating marketing campaigns, which may perceive the created campaigns differently. A properly designed and targeted advertising campaign with emotional appeal can create a strong emotional connection between the customer and the brand. The company can thus create added value that will support its sustainability in the market and competitive environment. In this context, in the conclusion, managerial implications, theoretical aspects, and limitations of our research were specified in more detail.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

A study by Raza et al. confirmed rational buying behavior in the case of Generations X and Y. They claimed that Generation Z was influenced more by social media and influencers, which could elicit 80% stronger and more memorable reactions [18]. Research by Raza et al. did not sufficiently confirm the rationality of the purchase behavior of Generation Z. Our study confirmed that depending on the generation span, there could be an emotional perception of advertising appeals [18]. Such perceptions can create an emotional connection between customers and brands and support their impulsive or irrational buying beliefs. Buying behavior under the influence of emotional advertising appeals can promote irrationality in the final decision to purchase a product.

Previous studies have found that advertising can evoke emotions; however, the challenge lies in channeling that emotion into a customer’s final decision. The target customer segment may be emotionally activated but not sufficiently to make a purchase. Traditional economic models of consumer behavior have placed products at the center of attention (the assumption of traditional economic effects). The emotional evaluation of attitudes towards a brand manifest only after purchasing a product [16]. A limitation of such previous studies is that they did not consider the effect of emotional advertising appeals on purchasing behavior. The present study focused on determining emotional attitudes toward a brand after purchasing a given product. The contribution of our study is that emotional appeals used in advertising spaces can support purchasing behavior. This implies that emotional behavior may not occur immediately after purchasing a product. Such behavior can also be created through advertising that focuses on a certain social issue, perception, or value evoked by social media.

There were significant differences in the perception of the emotional impact of advertising spaces between men and women [19]. A limitation of the study by Cartwright et al. was the general perception of emotional influence. In our study, we pointed to specific positive and negative moods after viewing an advertising campaign with an emotional impact. We found a greater negative impact on women than on men [19].

Lastly, Zollo et al. confirmed that cognitive processes and personal and social integration mediated the relationship between the marketing influence of social media advertisements and the generation of brand awareness as a function of age. Emotional brand experience can strengthen customer loyalty [22]. Our study found that we cannot perceive emotional advertising campaigns as those that aim to promote product sales. Their goal is to generate customer loyalty, reinforce their values, and reflect on their actions and considerations. The main contribution of our study is that advertising with an emotional appeal can create a certain form of positive or negative mood depending on the customer’s age. In this case, a strong emotional connection between the customer and the brand can be created. A company that promotes social motivation can evoke stronger emotions than one that simply spotlights a product [22,23].

6.2. Managerial Implications

Businesses must define the target segment to which they direct emotional advertising messages. Depending on the age, it is important to identify the impact of an emotional advertising campaign on the future purchasing behavior of customers, brand relationships, and customer loyalty. A company can create a strong emotional connection with its customers by properly targeting the customer segment and using an appropriate emotional appeal in response to current societal perceptions. Thus, social networks can conveniently promote emotional appeals, increasing the pressure on negative influencer behavior.

It is also important that the company creates an appropriate communication campaign between consumers (e.g., between parents and children). Businesses can use appropriate online and offline communication platforms to ensure effective consumer communication. In this way, the business can bring new knowledge to customers, which can help them better understand the concept of a brand or product. Simultaneously, the company can improve positive brand perceptions and communication between consumers.

Finally, businesses should apply appropriate elements of the associative model, which uses advertising emotional appeals to promote products and other motives with different levels of understanding. By appropriately connecting the product, brand, and emotional appeal in the advertising space, a company can gain a significant competitive advantage over its brand. Creating an emotional connection with the customer can promote the long-term sustainability of purchasing behavior. Thus, businesses can provide additional information on product quality, packaging, and effects to promote consumer interest in products. In this way, the company can also influence purchasing behavior among generations.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study had several limitations. Financial constraints and the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impeded the study, preventing direct customer interaction. Future studies should incorporate other fields, such as psychology and neurology. Future research should focus on the analysis of structural and functional changes in brain structures in connection with the implementation of the purchase process and the monitoring of emotional advertising campaigns using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with a magnitude of a Tesla 3. Such research should investigate the activation of brain structures bilaterally (right- and left-brain hemispheres) during the final decision to purchase selected products. These results can be linked to the fields of psychology and marketing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V. and A.K.; methodology: D.V. and A.K.; software, D.V.; validation, D.V. and A.K.; formal analysis D.V.; investigation, D.V.; resources, A.K.; data curation, D.V.; writing—original draft preparation, D.V. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, D.V. and D.V.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, D.V.; project administration, A.K.; funding acquisition, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is an output of scientific project VEGA no. 1/0032/21: marketing engineering as a progressive platform for optimizing managerial decision-making processes in the context of the current challenges of marketing management.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Zabkar, V.; Diamantopoulos, A. The unobserved signaling ability of marketing accountability: Can suppliers’ marketing accountability enhance business customers’ value perceptions? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clore, G.L. Psychology and the rationality of emotion: Psychology and the rationality of emotion. Mod. Theol. 2011, 27, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajanova, L.; Nadanyiova, M.; Lazaroiu, G. Specifics in brand value sources of customers in the banking industry from the psychographic point of view. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2020, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, V.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Long live the marketing mix. Testing the effectiveness of the commercial marketing mix in a social marketing context. J. Soc. Mark. 2020, 10, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaz, F. The digital and physical footprint of dark net markets. J. Int. Mark. 2020, 28, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, C.; Franco, M. Influence of emotions on decision-making. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2016, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clore, G.L.; Huntsinger, J.R. How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, A.K. Influence of hedonic and utilitarian motivation on impulse and rational buying behavior in online shopping. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2020, 23, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yao, D.; Chen, X. Happiness begets money: Emotion and engagement in live streaming. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 58, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, G.F.; Farrelly, F.J.; Conduit, J. Market intelligence dissemination practices. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Yang, X.C.; He, Z.X.; Wang, J.G.; Bao, J.; Gao, J. The Impact of Positive Emotional Appeals on the Green Purchase Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 716027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindauer, M.; Myorga, M.; Greene, J.; Slovic, P.; Vastfjall, D.; Singer, P. Comparing the effect of rational and emotional appeals on donation behavior. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2020, 15, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Tiberio, L.; Mastandrea, S.; Chokrai, P.; Fritsche, I.; Klockner, C.A.; Masson, T.; Vesely, S.; Panno, A. Psychological Predictors of Energy Savin Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranzbühler, A.-M.; Zerres, A.; Kleijnen, M.H.P.; Verlegh, P.W.J. Beyond valence: A meta-analysis of discrete emotions in firm-customer encounters. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.K.; Ilavarasan, P.V. Pre- and post-launch emotions in new product development: Insights from twitter analytics of three products. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarantino, A.; Hareli, S.; Hess, U. Emotional Expression as Appeals to Recipients. Emotion 2022, 22, 1856–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azemi, Y.; Ozuem, W.; Wiid, R.; Hobson, A. Luxury fashion brand customers’ perceptions of mobile marketing: Evidence of multiple communications and marketing channels. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Zaman, S.U.; Qabool, S.; Alam, S.H.; Ur-Rehman, S. Role of Marketing Strategies to Generation Z in Emerging Markets. J. Organ. Stud. Innov. 2022, 9, 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.; McCormick, H.; Warnaby, G. Consumers’ emotional responses to the Christmas TV advertising of four retail brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barve, G.; Sood, A.; Nithya, S.; Virmani, T. Effects of Advertising on Youth (Age Group of 13–19 Years Age). J. Mass Commun. J. 2015, 5, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berne-Manero, C.; Marzo-Navarro, M. Exploring how influencer and relationship marketing serve corporate sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, L.; Filieri, R.; Rialti, R.; Yoon, S. Unpacking the relationship between social media marketing and brand equity: The mediating role of consumers’ benefits and experience. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; O’Shaughnessy, J. The role of emotion in advertising. Psychol. Mark. 1984, 1, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, J. Consumer Behaviour: Perspectives, Findings and Explanations; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-137-00376-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V. Marketing research. In Handbook of Marketing Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, M.R.; Dahl, D.W.; White, K.; Zaichkowsky, J.L.; Polegato, R. Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Broderick, A.J.; Chamberlain, L. What is ‘neuromarketing’? A discussion and agenda for future research. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2007, 63, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P. Measuring the dimension of psychological general well-being by the WHO-5. Qual. Life Newsl. 2004, 32, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dzuka, J.; Dalbert, C. Development and validation of emotional habitual subjective well-being (SEHP) scales. Czechoslov. Psychol. 2002, 43, 234–250. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.B.; Xing, J.Y. The Impact of Social Media Information Sharing on the Green Purchase Intention among Generation Z. Sustainability 2023, 14, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G.; Batterham, A.M.; Jones, H.; Taylor, C.E.; Willie, C.K.; Tzeng, Y.-C. Appropriate within-subjects statistical models for the analysis of baroreflex sensitivity. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2011, 31, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralova, Z.; Skorvagova, E.; Tripakova, A.; Markechova, D. Reducing student teachers’ foreign language pronunciation anxiety through psycho-social training. System 2017, 65, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casais, B.; Pereira, A.C. The prevalence of emotional and rational tone in social advertising appeals. RAUSP Manag. J. 2021, 56, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Butt, S.R.; Murad, M.; Mirza, F.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Untying the Influence of Advertisements on Consumers Buying Behavior and Brand Loyalty Through Brand Awareness: The Moderating Role of Perceived Quality. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 803348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N.; Verma, D.; Kumar, D. Evolution and trends in consumer behaviour: Insights from Journal of Consumer Behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 2023, 22, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Dove #Detoxyourfeed Campaign Exposes Toxic Beauty Tips Social Feeds. 2022. Available online: https://mediashotz.co.uk/dove-detoxyourfeed-campaign-exposes-toxic-beauty-tips-social-feeds/ (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Byrd, A. DetoxYourFeed: Creating an Online Narrative of Self-Love for Today’s Youth. 2022. Available online: https://www.prnewsonline.com/dove-detox-your-social-media-feed/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Fardi, M. Investigate the role of advertising appealing in brand attitude and customer behavior. Humanidades Inov. 2021, 8, 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Levirni, G.R.D.; Santos, M.J. The influence of price on purchase intentions: Comparative study between cognitive, sensory, and neurophysiological experiments. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krestyanpol, L. Social engineering in the concept of rational and irrational consumer behavior. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 961929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.G. Advances in human factors in communication of design. In Proceedings of the AHFE 2019 International Conference on Human Factors in Communication of Design, Washington, DC, USA, 24–28 July 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 974. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).