2.1. Literature Review

Food is an essential component of travel; as it is a basic daily need, it constitutes a significant portion of travel expenses [

26]. According to Wolf and the World Food Travel Association [

27], travelers spend approximately 25% of their travel budget on food and beverage (F&B). This percentage can reach up to 35% in expensive destinations and drop to around 15% in more affordable ones. Because gastronomic tourists (i.e., tourists whose main reason for travel is to indulge in culinary experiences) do not merely eat to satisfy their hunger but also wish to explore the local gastronomy, they generally spend more than the average 25% that is spent by travelers [

27,

28,

29].

Gastronomy has become an important feature of tourism. It is a creative part of cultural tourism, enabling tourists to discover a destination through its food, wine, and culture [

30]. Experiencing gastronomy while on vacation has been compared with the “consumption of local heritage” [

3]. One’s memories of a place can be strongly associated with the gastronomic experiences that they had there and the people that they shared them with. Destinations can be perceived not only visually but also in terms of soundscape, smellscape, and tastescape [

31]. Certain foods become synonymous with specific locations, for example, hot dogs with New York, kebab with Istanbul, gyros with Greece, sauerkraut with Germany, and paella and tapas with Spain [

32]. In Mediterranean destinations such as Italy and France, gastronomy holds a central role as a principal, core resource. This is the cradle of haute cuisine featuring upscale gastronomic establishments, luxury and gourmet restaurants, and fine dining. However, in most destinations, gastronomy is still considered a supporting resource as the destination’s image is associated with other resources such as culture or recreation; therefore, gastronomy can play a pivotal role in positioning and developing undifferentiated primary resources [

5,

33].

Gastronomic tourism is still a rather new topic within the tourism industry, and it has gained increased attention since the turn of the millennium; it establishes connections between tourists and the destination’s culture [

34]. Bornhorst et al. [

35] argue that a destination’s success hinges on a unique location, accessibility, attractive products and services, quality visitor experiences, and community support. Destinations thus face the challenge of shaping an appealing multidimensional offer, and it can be said that the success of a tourism business is the outcome of a destination’s competitive tourism offer [

36].

(Service) quality can play a vital role in enhancing the competitiveness of a tourism destination as it serves as a source of competitive advantage. Martin [

37] defines service quality as “the ability to consistently meet external and internal customer needs, wants, and expectations involving procedural and personal encounters”. Many scholars have employed modified versions of the original SERVQUAL model proposed by Parasuraman et al. [

22] to measure service quality across various types of services (e.g., DINESERV: Stevens [

23], DINESCAPE: Ryu and Jang [

38], etc. [

21,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]) (

Table 1).

Quality is a prerequisite for perceived value, which is a multidimensional concept representing a “trade-off between benefits and sacrifices, as perceived by customers” [

58] and which is also a prerequisite for competitiveness as well. If we transfer the concept of quality from the entrepreneurial level to the destination level, we can conclude that a destination that reflects overall quality is also competitive. Quality can thus be understood as “the ability to optimize the attractiveness of a destination’s resources in order to offer high-quality, unique, and destination-specific tourism services, resulting in effective and sustainable use of its resources” [

59,

60]. Morrison [

61] argues that physical structures and their size are not as significant to visitors compared with their quality; the quality of services provided by the staff, including their hospitality, and the welcoming attitude of residents are also significant factors. Quality management therefore plays a crucial role in the development of a destination’s offer [

61,

62].

Competence is an important resource for determining competitive advantage; resource distinctiveness arises through the identification of a unique pattern of competences [

63]. The quality of competitive advantage depends on the quality of interaction processes (coordination of resources and competences) and on the quality of resources and competences contributed by business partners [

64,

65]. By definition, competence (or competency) “is the ability to do something” and is “the quality of being competent”, with the primary focus being on competent individuals who possess the ability or capability to complete the task [

66]. Competence can be categorized as: (1) individual competence that focuses on the personal and cognitive traits of competent managers or employees in relation to their job performance; (2) organizational competence that focuses on corporation-wide strategic competence and collective practices; and (3) comprehensive competence that integrates both individual and organizational strategic competences [

67]. Therefore, “the factors governable by the organizations, which make them survive and succeed, are the competence factors—and of the whole of those factors from a work effort of the simplest floor person to the biggest technological breakthroughs and financing possibilities; everything within the boundaries of an organization that enables its performance, belongs to its competence” [

68]. Because a destination, being a legal entity (a non-living thing), possesses organizational competences, it can also possess destination competences. Consequently, destination competences encompass everything within a destination’s boundaries that enables its performance and success. Based on this observation, we define destination competences in our model as everything within the boundaries of a destination that enables its performance and success, including: (1) destination resources (core and supporting resources), (2) gastronomic resources (restaurant quality and service quality), and (3) GDC (quality, innovativeness, creativity, sustainability, and local features).

Furthermore, Hjalager [

69] argued that the destination serves as a repository of competence and knowledge, which is crucial for the development of products and services (i.e., the destination offer). Intellectual capital, being a set of intangible resources and capabilities comprising different categories of knowledge, contributes to a competitive advantage and consists of: (1) human capital (knowledge, experiences, skills, and motivation embedded in employees), (2) structural capital (methods, capabilities, routines, and procedures embedded in the organization), and (3) relational capital (capabilities, knowledge, and procedures embedded in the organization and arising from relationships with suppliers, customers, partners, and others) [

70].

Destination competitiveness is a highly significant topic in tourism, and numerous studies have been conducted to study this element. A groundbreaking contribution is Ritchie and Crouch’s Conceptual model of destination competitiveness [

71], which offers a comprehensive interpretation of destination competitiveness by asserting that a destination’s competitiveness depends on its ability to generate and/or increase tourism expenditure. Today, competition among destinations is no longer only focused “on the single aspects of the tourism product”; rather, it is viewed as an “integrated and compound” set of tourism services that form the destination offer [

36,

72]. Therefore, a destination that places a strong emphasis on gastronomic tourism with a high level of gastronomy can be referred to as a gastronomic destination.

2.2. Model Development

To measure the perceived quality of restaurants and hence of gastronomic destinations, we modified and upgraded the DINESERV model [

23], which originates from the SERVQUAL model [

22]. The new model is called GADECOMP (GAstronomic DEstination COMPetitiveness). It comprises selected dimensions of the following supplemented SERVQUAL model versions:

DINESERV (Stevens et al.; Kim et al. [

23,

73]), which measured the quality of a restaurant’s services;

DINESCAPE (Ryu and Jang, [

38]), which measured the quality of a restaurant’s physical environment;

GRSERV (Chen et al. [

21]), which measured the service quality in green restaurants (and thus including sustainability) as well as parameters suggested by the author.

We combined the competence parameters from the three abovementioned service quality model versions that have best described restaurant services (DINESERV), the restaurant physical environment (DINESCAPE), and restaurant green practices (GRSERV). To eliminate the shortcomings of the three existing quality systems and achieve a more holistic service quality model, we added the following crucial competence parameters: local features (as part of social responsibility, which in this research is considered as imminent in sustainability) and innovativeness and creativity. The dimensions of innovativeness and creativity were described as crucial in previous research on restaurant innovativeness [

74,

75]. The competences examined in this study, namely quality, innovativeness, creativity, sustainability, and local features, are all crucial for the differentiation process and are thus crucial for competitiveness in today’s demanding and increasingly saturated tourism market.

The novel method applied herein relates to the transfer of perceived quality measurement from the entrepreneurial level to the destination level. The approach for GD competitiveness measurement was based on the quality measurement on the demand side. Unlike the famous destination competitiveness models ([

71,

76,

77,

78,

79]) that employ a supply-side approach, we adopted a destination competitiveness model and applied it from the demand-side perspective. This allowed us to incorporate and put into a broader context selected dimensions from the following models: (1) Ritchie and Crouch’s conceptual model of destination competitiveness [

71], (2) Goffi’s determinants of tourism destination competitiveness: a theoretical model and empirical evidence [

79], and (3) Koch’s model of the dimensions of tourism quality in a destination [

80], as well as (4) parameters suggested by the author.

According to the GADECOMP model, the destination resources create its comparative advantages (i.e., destination resources derived from nature, such as pristine nature, climate, cultural and social attractions) and competitive advantages (i.e., a skilled, creative, and sustainability-oriented workforce comprising restaurant chefs, highly competent local cooks, sommeliers, waiters, restaurant managers, restaurant owners, interior designers, supporting infrastructure, tourism facilities, DMOs, and local businesses) in or keep the to the GDO. These resources are categorized as core resources and supporting resources according to Ritchie and Crouch [

71]. Sánchez-Cañizares and López-Guzmán [

81] define gastronomy as a tourism resource. Because we assume that gastronomy is one of destination’s main pull factors, we define the gastronomic offer as a gastronomic resource and place it among the core resources of a tourism destination. Therefore, in the model, the destination offer includes core and supporting resources. Gastronomy (i.e., gastronomic resources and restaurants as the most important part of a GDO), sports and recreation (accompanying sports and recreational activities for gastronomic tourists in pristine natural environments and in a pleasant climate), and culture and entertainment (cultural attractions and entertainment options, including dance, music, festivals, workshops, etc.) are all considered core resources of a GD. Supporting resources consist of tourism facilities (accommodations, restaurants, attractions, and leisure activities), general infrastructure (accessibility, safety and security, proximity to other destinations, transportation quality, environmental quality, care for sanitation, and sewage and waste), and other destination assets (hospitability of local residents, presence of local businesses, destination image, and DMO).

To become competitive, a GDO must embody quality, innovativeness, creativity, sustainability, and local features as its indispensable competences. The destination’s resources were assessed using the GDCs mentioned above. The competences all collectively influence the customers’ perceived value of the destination through the perceived quality of restaurants. Perceived quality—as a prerequisite for competitiveness—allows us to measure a GD’s competitiveness using the novel GADECOMP model through the use of the consumers’ perception as a subjectively measurable indicator.

2.3. Hypotheses Development

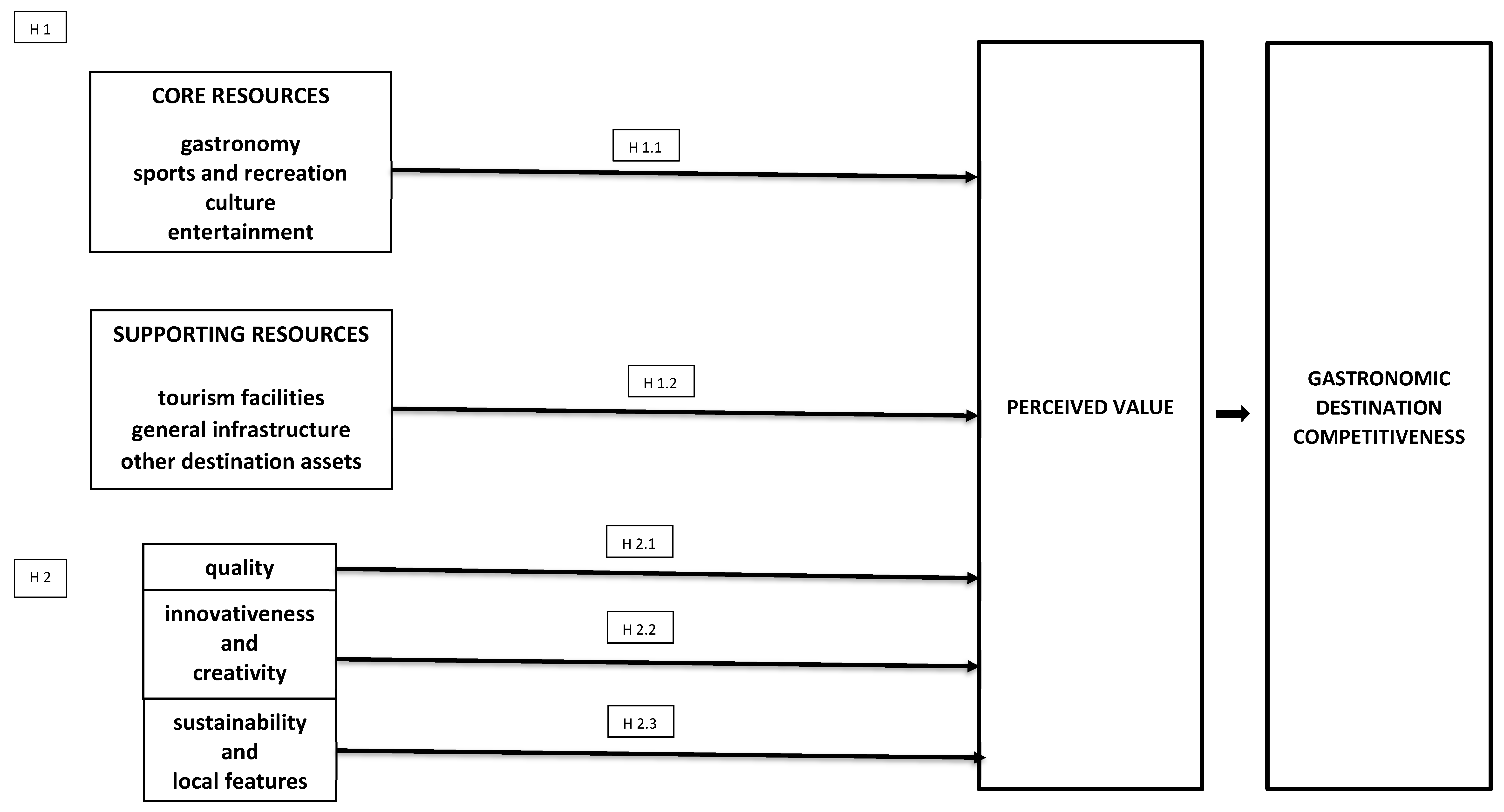

In line with the introduction, literature review, and model development, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis H1. GDO has an impact on the perceived value of restaurants.

Hypothesis H1.1. The destination’s core resources have an impact on the perceived value of restaurants situated in this destination.

Hypothesis H1.2. The destination’s supporting resources have an impact on the perceived value of restaurants situated in this destination.

Destinations usually develop their offer based on the types of resources that they possess, which must all work together to create a destination that is competitive, attractive, creative, sustainable, authentic, and unique [

82]. Gastronomy, for example, has recently been acknowledged as one of the most important destination resources [

8]. Core resources, such as gastronomy, culture, sports and recreation, and entertainment, are the primary elements that attract tourists and motivate their decision to choose a specific destination. Supporting resources, such as tourism facilities, general infrastructure, and other destination assets, merely complement the core resources and are not the prime motive for travel; rather, they provide a foundation for a successful tourism offer [

71,

79]. This method of classifying destination resources was applied in this research.

Core and supporting resources must reflect quality. According to Henderson [

83], gastronomy enhances guests’ sense of participation and attachment to a location, whereas a poor quality of the gastronomy offer (i.e., food and beverage (F&B) or service quality) can have a negative impact on the destination’s reputation.

To survive, thrive, and position themselves in an environment of fierce competition, destinations must know, understand, and satisfy their guests’ needs and use their resources effectively [

84]. Dwyer and Kim [

77] adopted an approach to measure destination competitiveness based on Porter’s diamond model [

85] and Ritchie and Crouch’s model [

71]. Moreover, Vengesayi [

86], Ferreira and Estavo [

87], Khin et al. [

88], and the World Economic Forum [

89] have used a similar categorization of supporting resources in the destination competitiveness models and indicators to our own; namely, they included attractions, general infrastructure, destination management, destination image, local business environment, human resources, environment, openness, etc. According to Chin [

90], it is crucial for a destination’s competitiveness to bolster its supporting resources, which is especially true for rural tourism destinations. Bornhorst et al. [

35] argued that a unique and accessible location, well developed infrastructure, quality visitor experience, attractive products and service offerings, and community support are crucial for a destination’s success. Destinations thus face the challenge of creating an appealing multidimensional offer that includes both core resources and supporting resources. In essence, the success of a tourism business is determined by the destination’s competitive tourism offer [

36]. This shows that a holistic approach is essential for a successful destination offer development.

Hypothesis H1 aims to investigate whether a destination’s offer (i.e., its core and supporting resources) has any impact on the perceived value of restaurants through perceived quality, which is its prerequisite. A tourism destination is more appealing to tourists if it offers them great value. According to Gomezelj Omerzel and Mihalič [

78], “destination management should take care in creating and integrating value in tourism products and resources so that a tourism destination can achieve a better competitive advantage”. Barney [

91] and Mior Shariffuddin et al. [

92] suggested that a destination’s competitive advantages, particularly the ones derived from unusual, precious, incomparable, or inimitable tangible and intangible resources, indeed strengthen the destination’s competitiveness. The availability of resources is of significant concern for destinations, businesses, or industries, as it helps them to sustain long-term competitiveness [

93]. Therefore, mainly tourism destination competitiveness was measured by categorizing tangible and intangible core and supporting resources. Basle [

94], however, adopted an approach to measure the competitiveness of a gastronomic destination based on the perceived quality of its resources, which is a prerequisite for competitiveness, as perceived and valued by tourists.

Quality is a prerequisite for perceived value [

58]. If a destination’s offer reflects quality, it is perceived as more compelling to tourists. The research addressing quality and tourism has been approached by researchers in various contexts, e.g., perceived quality of a destination in connection to visitor satisfaction and their behavioral intentions [

95,

96,

97,

98]; quality of a tourism destination [

99,

100,

101,

102]; destination quality management best practices [

103]; tourist judgement on the service quality of winter sport destinations [

104]; analysis of the quality of service in gastronomic festivals in a tourist destination of Ecuador [

57]; the overall quality of tourism services in Kashmir Valley [

105]; the relationship between tourism service quality and destination loyalty through destination image in the Dead Sea tourism destination of Jordan [

106]; the economics of reputation and quality decisions for a tourism destination with implications for competitiveness [

107]; competitiveness through quality in the hospitality industry [

60]; destination environment quality [

108]; and quality tourism experience [

109]. Moreover, some applications of the SERVQUAL model [

22] were developed while measuring the service quality of destinations, such as the TOURQUAL model [

49]; the HISTOQUAL model [

42]; the LODGQUAL model [

45]; the LODGSERV model [

47]; the HOTELQUAL model [

110]; and the HOLSAT model [

53] (see

Table 1).

Previous studies on value in tourism have primarily focused on the perceived value for tourists (since the 2000s); however, none of the studies have expanded and modified SERVQUAL application models to assess the quality of core and supporting resources within the destination offer (Ritchie and Crouch categorization, [

71]) or transferred the model from the entrepreneurial level to the destination level to measure destination competitiveness based on perceived quality.

Hypothesis H2. GDCs have an impact on the perceived value of restaurants.

Hypothesis H2.1. The quality of upscale restaurant resources has an impact on the perceived value of restaurants.

Hypothesis H2.1.1. The tangible upscale restaurant quality has an impact on the perceived value of restaurants.

Hypothesis H2.1.2. The intangible upscale service quality has an impact on the perceived value of restaurants.

Hypothesis H2.2. Innovativeness and creativity have an impact on the perceived value of restaurants.

Hypothesis H2.3. Sustainability and local features have an impact on the perceived value of restaurants.

The destination offer should reflect competences. This is particularly true for gastronomic resources such as restaurants. In addition to offering quality F&B that is produced using local ingredients, restaurants should employ qualified staff that are able to offer quality services, keep pace with modern trends of sustainability, and be innovative and creative. Altogether, these factors generate the necessary added value to a restaurant and thus to gastronomic resources.

The link between quality and perceived value has been discussed in various studies on service quality perception in the restaurant and hotel industry [

24,

111,

112,

113,

114] (see also

Table 1), but not as much in the context of upscale restaurants. The importance of quality and tangible restaurant resources was researched by Ryu and Jang [

38] in an applied quality model known as DINESCAPE. The quality of a restaurant’s tangible environment (price fairness, physical environment, and cleanliness) was explored from the perspective of customer retention [

115]; however, the quality of intangible services, “the appropriateness of assistance and support provided to a customer and the value and benefits received for the price paid” [

116], is difficult to judge. Reliable evaluation criteria in this regard include price, the physical environment of the service, and the taste of the F&B served, which create an overall perceived value. Service quality (sometimes also referred to as perceived quality) is an important antecedent of perceived value [

117,

118,

119], which is a “customer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given” [

120]. Perceptions are very subjective and depend upon cultural standards, individual cultural profiles, previous experiences, and guests’ expectations [

116]. Consumers are no longer paying just for the basic service but for the complete experience; they are willing to pay a premium for the added value offered by experiences that are above standard services [

121]. Experiences can touch people better than products and services. They are intangible, immaterial and tend to be expensive; however, they are memorable and highly appreciated [

122]. Similarly to how the destination experience is a fundamental destination product, the dining experience is a crucial restaurant product [

3]. Dining experiences are influenced by the overall service, i.e., what is served and how it is served, as well as where it is served [

123]. This article therefore examines both the restaurant’s physical environment and service quality in upscale dining.

The main challenge of this century is innovation, which has encompassed both invention and its successful commercialization [

124,

125]. The terms innovation and innovativeness, although interchangeably used in the business and hospitality literature, significantly differ. “Innovation focuses on the outcomes of new elements or a new combination of traditional elements in a firm’s activities, while innovativeness refers to a firm’s capability to be amenable to new ideas, services and promotions” [

75,

126,

127,

128]. Creativity, which is closely linked to innovation and novelty, represents an organization’s ability to generate fresh and useful ideas at different stages of the innovation process, utilizing available knowledge to make new discoveries [

129]. Although creativity and innovation are sometimes interchangeably used in the literature, they have distinct meanings. Creativity focuses on the generation of new and original ideas, while innovation involves the implementation of these creative ideas [

130]. Additionally, diversity is seen as the main resource for fostering creativity [

131]. Creativity without innovation is just one more idea, while innovation that is not based on new and novel ideas does not add value. Hence, creativity and innovation are integral components of the overall innovation process [

130,

132].

Innovation (innovativeness) is not only a precondition for improving business but also a means to express quality [

133]. The higher the restaurants’ innovations in products and services, the higher the quality perceived by the guests [

134] in fine-dining restaurants [

74,

135,

136]. However, previous research on innovation in the restaurant sector is scarce, and it has mostly focused on new product development (e.g., molecular gastronomy) and technical innovations concerning cooking methods and the use of technology [

137,

138]. More recent studies on innovativeness in restaurants include innovation in restaurant management [

137], innovative organizational culture in the restaurant industry to improve restaurants’ business performance [

139], and innovative capabilities enhancing the internationalization of restaurants (i.e., developing new dishes, using modern equipment, using new technologies, and updating menus) [

140]. The tourism and hospitality literature pays less attention to innovativeness compared with the general business literature [

75]. Innovation has mostly been researched through the lens of companies and entrepreneurs in terms of profitability, success, and market value [

141]; this same approach was used when analyzing the impacts of innovation in hospitality and tourism [

142,

143,

144,

145,

146,

147,

148].

Dimensions of innovativeness and creativity were interlinked with studies on the perceived upscale restaurants’ image, the perceptions of price fairness and post consumption behavioral intention [

135,

136], and the perceived value of restaurant innovativeness [

75] and creative tourism destinations [

149]. Guan et al. [

150] explored the relationship between customer knowledge sharing, creativity, and customer-perceived economic value creation. Some interesting research on restaurant innovativeness [

151] was associated with customer perception [

75].

According to Milfelner [

152], theoretical contributions and empirical evidence show that innovation sources—both innovativeness and innovation capacity—are the sources that fulfil every requirement and have the potential to achieve competitive advantages. Competitiveness was explored in studies on innovativeness in tourism [

153,

154,

155]. Evans [

156] suggested that branding based on cultural and creative resources is crucial for the competitive position of businesses, regions, and cities.

Sustainability, whose concept originates in the 1970s but has roots dating back to Roman times, encompasses considerations for the environment, people, and economy, with a primary focus on environmental aspects [

17]. Its fundamental goal is to ensure a better quality of life for both present and future generations [

157]. Sustainability therefore aims to strengthen the quality of the destinations and their image. Moreover, environmentally conscious tourists are willing to pay higher prices for destination products that are responsible and sustainable [

17,

158]. Consequently, sustainable (destination) products are perceived as upscale, which makes them particularly important for upscale gastronomy. The concept of sustainability is intrinsically linked to local features (sometimes also referred to as locality; [

159,

160]). The term local is directly associated with sustainability, authenticity, quality, and community, and it holds the potential to create a destination’s competitive advantage [

157,

161]. While extensive research has been conducted on sustainability, local features within the context of tourism have not yet been widely explored.

Research on sustainability in restaurants is relatively recent. There is a growing interest in green consumption and environmental protection within the restaurant industry [

162,

163,

164]. For instance, Filimonau et al. [

165] explored innovative trends in menus that promote sustainability in terms of responsible consumer choices. Liu et al. [

166] investigated how creative menus lead to favorable consumer responses, including positive attitudes towards the menu and enhanced perceptions of brand healthiness. Because of the growing environmental awareness among consumers, sustainable practices are being applied in food systems as well, including food miles, slow food, local food, etc. [

167,

168,

169]. Sustainability has been linked with local features in various contexts [

20,

159,

160,

170,

171]. The marketing literature has contributed to the understanding of consumer behavior towards green restaurants [

172], while other research has focused on management aspects, such as green supply chain management [

173] and sustainability management [

174]. There is also a link between sustainability and competitiveness, as businesses are believed to benefit from adopting environmentally friendly practices [

175,

176]. Because sustainability is closely intertwined with local features, Malecki [

177] suggested that creating and imitating competitiveness based on local knowledge and local culture can be difficult.

Hypothesis H2 aims to investigate whether GDCs (i.e., quality, innovativeness, creativity, sustainability, and local features) have any impact on the perceived value of restaurants. If a restaurant focuses on sustainability and local features in addition to being creative, innovative, and thus authentic, it undoubtedly creates value for guests; however, no research has yet focused on the above five concepts and perceived value in restaurants simultaneously in an integrated manner.

The link between sustainability and perceived value has not yet been thoroughly explored. Previous research has revealed how consumers perceive restaurants with green attributes and how this influences their behavioral intentions [

178,

179,

180]. Further research has shown that sustainability practices contribute to competitiveness and consumer satisfaction [

181], enhance customer value [

182], strengthen the role of customer behavior in shaping a perceived value for restaurants [

183], positively impact green restaurant image and revisit intention through perceived service quality [

184], etc. Outside the restaurant sector, Flagestad and Hope [

185] showed how a winter sport destination can create sustainable value to achieve strategic success, while Kataria et al. [

186] focused on the perceived value of sustainable brands in India.

Likewise, local features have not yet been extensively explored in connection to perceived value. In the restaurant sector, consumers show great interest in green practices that directly affect their well-being, such as the use of organic and locally grown ingredients. These components increase their perceived value of restaurants [

187]. Because local food is perceived as healthy, [

188] illustrates how perceived food healthiness in restaurants influences value, satisfaction, and revisit intentions. Regarding traditional food as a type of local resource, Chen et al. [

189] found that consumers who feel more nostalgic about traditional restaurants, thus being exposed to local features, tend to perceive a higher value of their dining experience. Konuk [

190] investigated the role of perceived food quality, price fairness, perceived value, and customer satisfaction on consumers’ intentions to revisit organic food restaurants. The research has expanded to regional wines and has investigated wine consumers’ perceptions about regional environments, which are associated with their perceived value of purchasing regional wine [

191].

The developed hypotheses and sub-hypotheses are presented in the following

Figure 1.