Integration of Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Policy and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions in China: Progress and Highlights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Approach and Methodology

2.1. ILK-Integration Framework

Knowledge, experience, innovation, or practice of current or potential values which have been accumulated and developed by local residents or communities within certain areas over a long period of time and passed on from generation to generation[37]. (Translated by authors)

| Category | Pathway | Definition | Pros and Cons | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct mention of “knowledge” (and synonyms) in Chinese policies | Knowledge preservation | Protection of traditional and local cultures, knowledge, techniques, and skills in design, implementation, and management | Pro: a dedicated institution for knowledge identification and protection Con: requirements for sufficient budgets and professional personnel | [18,32] |

| Knowledge adoption | Active consideration, evaluation, and adoption of traditional and local cultures, knowledge, techniques, and skills in design, implementation, and management | Pro: maximizing the value of ILK and exploring potential benefits Con: requirements for appropriate ILK identification, professional personnel, and proper channels for adoption | [14,17,18] | |

| No direct mention of “knowledge” (and synonyms) in Chinese policies | Education | Official promotion of ideas, knowledge, and skills to communities | Pro: impacts a wider community; ties with nature from a young age Con: requirements on a certain level of literacy for recipients; requirements for appropriate recognition of ILK significance and components | [38,39] |

| Supervision | Right of the community to track the progress, report issues and suggestions, and enable adaptive management | Pro: adaptative management by virtue of deep understandings of environmental and social dynamics Con: challenges on providing sufficient rewards and long-term incentives | [1,36] | |

| Participation | Community engagement with design, implementation, and management in a general way | Pro: emphasis on hearing and respecting community voices Con: challenges on ensuring adequate participation with appropriate mechanisms | [11,15,35] |

2.2. Policy Data Collection and Analysis

2.3. Exemplar Case Selection and Analysis

3. Policy Analysis Results and Discussion

3.1. Indigenous Groups Identification

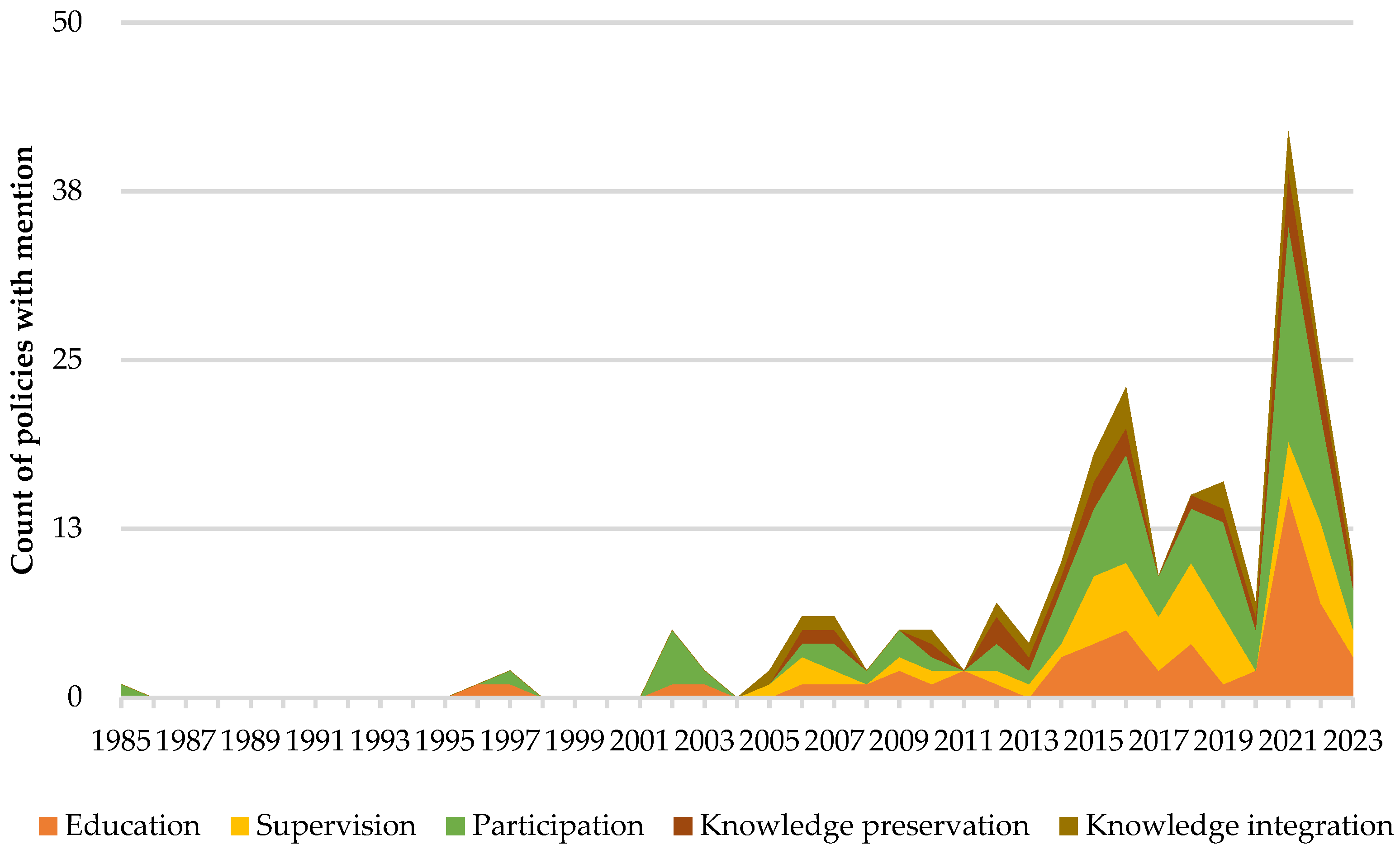

3.2. Overall Trends in ILK Integration

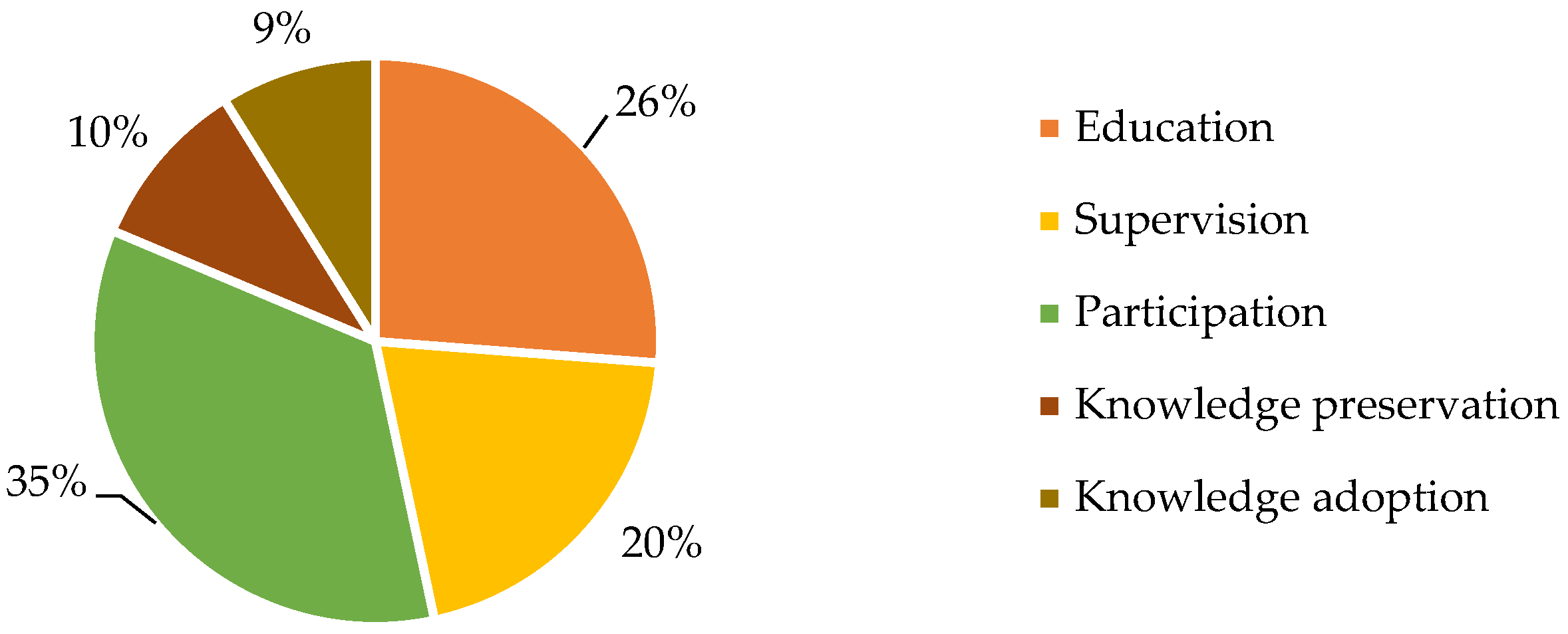

3.3. Pathways to ILK Integration

3.4. Major Groups and Application Fields under Five Pathways

4. Typical NbS Cases Featured with ILK in China: Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Case Background

4.1.1. Qiandao Lake Water Fund

4.1.2. Yunnan Snub-Nosed Monkey Protection Network

4.1.3. Laohegou Land Trust Reserve

4.2. Case Analysis of ILK Integration

4.2.1. Practices and Lessons from the Three NbS Cases in China

4.2.2. Comparison with International Practices

4.3. The Role of Policies, Implementation Highlights, and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IUCN. IUCN Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions, 1st ed.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2020.

- UN Environment Programme. UN Environment Assembly Concludes with 14 Resolutions to Curb Pollution, Protect and Restore Nature Worldwide. Available online: http://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/un-environment-assembly-concludes-14-resolutions-curb-pollution (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- World Bank. Biodiversity, Climate Change, and Adaptation: Nature-Based Solutions from the World Bank Portfolio; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Indigenous Knowledge for Biodiversity Conservation. Ambio 1993, 22, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Negi, V.S.; Pathak, R.; Thakur, S.; Joshi, R.K.; Bhatt, I.D.; Rawal, R.S. Scoping the Need of Mainstreaming Indigenous Knowledge for Sustainable Use of Bioresources in the Indian Himalayan Region. Environ. Manag. 2021, 72, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosen, N.; Nakamura, H.; Hamzah, A. Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key? Sustainability 2020, 12, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Z.J.; Wijsman, K.; Tomateo, C.; McPhearson, T. How Deep Does Justice Go? Addressing Ecological, Indigenous, and Infrastructural Justice through Nature-Based Solutions in New York City. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 138, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiderska, K.; Argumedo, A.; Song, Y.; Rastogi, A.; Gurung, N.; Wekesa, C.; Li, G. Indigenous Knowledge and Values: Key for Nature Conservation; IIED: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J.; Robertson, A.; Rosen, F.D. Designing by Radical Indigenism. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2020, 8, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016.

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Andrade, A.; Dalton, J.; Dudley, N.; Jones, M.; Kumar, C.; Maginnis, S.; Maynard, S.; Nelson, C.R.; Renaud, F.G.; et al. Core Principles for Successfully Implementing and Upscaling Nature-Based Solutions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 98, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, H.; Balian, E.; Azevedo, M.; Beumer, V.; Brodin, T.; Claudet, J.; Fady, B.; Grube, M.; Keune, H.; Lamarque, P.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions: New Influence for Environmental Management and Research in Europe. Gaia Okologische Perspekt. Nat.-Geistes-Wirtsch. 2015, 24, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.P.; Guiomar, N. Nature-Based Solutions: The Need to Increase the Knowledge on Their Potentialities and Limits. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1925–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, B.; Yumagulova, L.; McBean, G.; Charles Norris, K.A. Indigenous-Led Nature-Based Solutions for the Climate Crisis: Insights from Canada. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiddle, G.L.; Bakineti, T.; Latai-Niusulu, A.; Missack, W.; Pedersen Zari, M.; Kiddle, R.; Chanse, V.; Blaschke, P.; Loubser, D. Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Climate Change Adaptation and Wellbeing: Evidence and Opportunities from Kiribati, Samoa, and Vanuatu. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 3056. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, G.; Brunet, N.D.; McGregor, D.; Scurr, C.; Sadik, T.; Lavigne, J.; Longboat, S. Toward Indigenous Visions of Nature-Based Solutions: An Exploration into Canadian Federal Climate Policy. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 514–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, C. Avoiding a New Era in Biopiracy: Including Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 135, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Gu, B.; Wang, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhai, H. Advances, Problems and Strategies of Policy for Nature-Based Solutions in the Fields of Climate Change in China. Clim. Change Res. 2021, 17, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M.; Sun, Y.; Rong, Y.; Hu, J. NbS practice in landscape engineering in Lishui city. China Land 2022, 439, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, J.C. Pathways of “Indigenous Knowledge” in Yunnan, China. Alternatives 2007, 32, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, M.J. China’s Indigenous Peoples? How Global Environmentalism Unintentionally Smuggled the Notion of Indigeneity into China. Humanities 2016, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. New Zealand-China Leaders’ Statement on Climate Change. Available online: https://english.mee.gov.cn/News_service/news_release/201904/t20190401_698078.shtml (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China; Ministry of Fiance of China; Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. Shanshui Lintian Hucao Shengtai Baohu Xiufu Gongcheng Zhinan (Shixing) [Project Guide for Ecological Protection and Restoration of Mountains, Rivers, Forests, Farmlands, Lakes, and Grasslands (for Trial Implementation)]. Available online: https://www.cgs.gov.cn/tzgg/tzgg/202009/W020200921635208145062.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Li, B.; Xue, D. Applicability and evaluation index system of the term “indigenous and local communities” of the Convention on Biological Diversity in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2021, 29, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of China. Guanyu Yinfa Zhongguo Shengwu Duoyangxing Baohu Zhanlue Yu Xingdong Jihua (2011–2030 Nian) [Notice on the Issuance of China’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan (2011–2030)]. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bwj/201009/t20100921_194841.htm (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. Quanguo Nongye Kechixu Fazhan Guihua (2015–2030 Nian) [National Plan for Sustainable Agricultural Development (2015–2030). Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/zcfg/qnhnzc/201505/t20150528_4622065.htm (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. “Shisiwu” Xiangcun Lvhua Meihua Xingdong Fang’an [The 14th Five-Year Plan of Action for Rural Greening and Beautifying]. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20221027153039525170128 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Beifang Fangshadai Shengtai Baohu He Xiufu Zhongda Gongcheng Jianshe Guihua (2021–2035 Nian) [Plan for the Construction of Major Ecological Protection and Restoration Projects in the Northern Sand Prevention Zone (2021–2035)]. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20220110163633586987237 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Nanfang Qiuling Shandidai Shengtai Baohu He Xiufu Zhongda Gongcheng Jianshe Guihua (2021–2035 Nian) [Plan for the Construction of Major Ecological Protection and Restoration Projects in the Hilly and Mountainous Regions of Southern China (2021–2035)]. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20220112104223124547639 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Dongbei Senlindai Shengtai Baohu He Xiufu Zhongda Gongcheng Jianshe Guihua (2021–2035 Nian) [Construction Plan of Major Ecological Protection and Restoration Projects in Northeast Forest Belt (2021–2035)]. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20220112104459162711942 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Townsend, J.; Moola, F.; Craig, M.-K. Indigenous Peoples Are Critical to the Success of Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change. Facets 2020, 5, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on Biological Diversity; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992; pp. 1–12.

- Gupta, M.C.; Gupta, S. Strengthening Community-Led Development of Adaptive Pathways to Rural Resilient Infrastructure in Asia and the Pacific. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2023, 8, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, W.; Freeman, M.; Freeman, B.; Parry-Husbands, H. Reshaping Forest Management in Australia to Provide Nature-Based Solutions to Global Challenges. Aust. For. 2021, 84, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sacco, A.; Hardwick, K.A.; Blakesley, D.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Breman, E.; Cecilio Rebola, L.; Chomba, S.; Dixon, K.; Elliott, S.; Ruyonga, G.; et al. Ten Golden Rules for Reforestation to Optimize Carbon Sequestration, Biodiversity Recovery and Livelihood Benefits. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1328–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of China. Quanguo Shengwu Wuzhong Ziyuan Baohu Yu Liyong Guihua Gangyao [The National Plan for the Protection and Utilization of Biological Species Resources]. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/zj/wj/200910/t20091022_172479.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Acharibasam, J.B.; McVittie, J. Connecting Children to Nature through the Integration of Indigenous Ecological Knowledge into Early Childhood Environmental Education. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoh, A.J.; Esongo, N.M.; Ayuk-Etang, E.N.M.; Soh-Agwetang, F.C.; Ngyah-Etchutambe, I.B.; Asah, F.J.; Fomukong, E.B.; Tabrey, H.T. Challenges to Indigenous Knowledge Incorporation in Basic Environmental Education in Anglophone Cameroon. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2022, 00219096221137645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Water Resources. Guanyu Jinyibu Qianghua Hezhang Huzhang Lvzhijinze de Zhidaoyijian [Guidelines on Further Strengthening the Duties of River and Lake Chiefs]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-01/01/content_5465754.htm (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- State Council Information Office of China. Zhongguo de Shaoshuminzu Zhengce Ji Qi Shijian [China’s Minority Policy and Its Practice]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2005-05/26/content_1131.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Cox, S. Poverty Eradication: A Chinese Success Story. Available online: http://za.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/sgxw/202210/t20221019_10785796.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China. Guanyu Yinfa Shisiwu Quanguo Chengshi Jichusheshi Jianshe Guihua de Tongzhi [Notice on the Issuance of the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Urban Infrastructure Construction]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-07/31/content_5703690.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ministry of Water Resources. Guanyu Jiakuai Tuijin Shengtai Qingjie Xiaoliuyu Jianshe de Zhidao Yijian [Guidelines on Speeding up the Construction of Ecologically Clean Small Watershed]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/15/content_5741554.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Quanguo Shidi Baohu Guihua (2022–2030 Nian) [National Wetland Protection Plan (2022–2030)]. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20230104172037356945593 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ministry of Land and Resources. Guanyu Jiaqiang Kuangshan Dizhi Huanjing Xiufu He Zonghe Zhili de Zhidao Yijian [Guidelines on Strengthening Restoration and Comprehensive Treatment of Geological Environment in Mines]. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/gwy/201611/t20161124_368161.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China. Tianranlin Baohu Xiufu Zhidu Fang’an [Systematic Plan for Natural Forest Protection and Restoration]. Available online: http://f.mnr.gov.cn/201907/t20190725_2449134.html (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Jianli Yi Guojiagongyuan Wei Zhuti de Ziranbaohudi Tixi de Zhidao Yijian [A Guideline on Establishing a System of Protected Natural Areas with National Parks as the Main Body]. Available online: http://f.mnr.gov.cn/201906/t20190627_2442400.html (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Jiakuai Tuijin Shengtai Wenming Jianshe de Yijian [Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of Ecological Civilization]. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/zcfg/qnhnzc/201505/t20150506_4581636.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of China. Ziran Baohuqu Guanli Pinggu Guifan [Code for Assessment of Nature Reserve Management]. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bgg/201712/t20171229_428892.htm (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China. Guojiaji Haiyang Baohuqu Guifanhua Jianshe Yu Guanli Zhinan [Guidelines for Standardized Construction and Management of National Marine Reserve]. Available online: http://gc.mnr.gov.cn/201807/t20180710_2079959.html (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Guojia Gongyuan Kongjian Buju Fang’an [National Park Spatial Layout Scheme]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-12/30/content_5734221.htm (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Guli He Zhichi Shehui Ziben Canyu Shengtai Baohu Xiufu de Yijian [Opinions on Encouraging and Supporting the Participation of Social Capital in Ecological Protection and Restoration]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-11/10/content_5650075.htm (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Quanmian Tuijin Xiangcun Zhenxing Jiakuai Nongye Nongcun Xiandaihua de Yijian [Opinions on Comprehensively Promoting Rural Revitalization and Accelerating Agricultural and Rural Modernization]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-02/21/content_5588098.htm (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China. Guanyu Cujin Xiangcun Lvyou Kechixu Fazhan de Zhidao Yijian [Guidelines on Promoting Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2018-12/31/content_5439318.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Xiangcun Zhenxing Zhanlue Guihua (2018–2022 Nian) [Strategic Plan for Rural Revitalization (2018–2022)]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-09/26/content_5325534.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Tuidong Chengxiang Jianshe Lvse Fazhan de Yijian [Opinions on Promoting Green Development of Urban and Rural Construction]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/21/content_5644083.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Zinda, J.A.; Trac, C.J.; Zhai, D.; Harrell, S. Dual-Function Forests in the Returning Farmland to Forest Program and the Flexibility of Environmental Policy in China. Geoforum 2017, 78, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, B. Towards Carbon Neutrality by Implementing Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme: Policy Evaluation in China. Energy Policy 2021, 157, 112510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Li, J.; Deng, J.; Lin, Y.; Ma, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, K.; Hong, Y. Eco-Environmental Vulnerability Assessment for Large Drinking Water Resource: A Case Study of Qiandao Lake Area, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2015, 9, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Mu, Q.; Wang, L.; Guo, F.; Ge, L. Nature-Based Solutions to Water Crisis Practice in China: Eco-Friendly Water Management in Qiandao Lake, Zhejiang Province. Nat. Prot. Areas 2021, 1, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Resources of China; IUCN. Typical Nature-Based Solutions Cases in China; Ministry of Natural Resources of China: Beijing, China; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2021.

- Iseman, T.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F. Nature-Based Solutions in Agriculture: The Case and Pathway for Adoption; FAO and TNC: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Su, X.; Han, W.; Liu, G. Potential Priority Areas and Protection Network for Yunnan Snub-Nosed Monkey (Rhinopithecus bieti) in Southwest China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 1211–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ding, W.; Xiao, W.; Ye, H. New Distribution Records for the Endangered Black-and-White Snub-Nosed Monkeys (Rhinopithecus bieti) in Yunnan, China. Folia Zool. 2019, 68, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China. Protection Network for the Yunnan Snub-Nosed Monkey; Zhongguo Shengtai Xiufu Dianxing Anli [Typical Case of Ecological Restoration in China]; Ministry of Natural Recourses of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- The Nature Conservancy. Annual Report on Overall Protection Network for Snub-Nosed Monkey Conservation in Yunnan. Available online: https://tnc.org.cn/content/details27_948.html (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Jin, T.; Ni, J.; Wang, J. Practice and Experience in the Protection of Public Welfare Protected Areas in Sichuan: An Example from Laohegou Nature Reserve in Pingwu County. In Sichuan Ecological Construction Report (2018); Sichuan Bluebook; Social Sciences Literature Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Term | Exemplar Policy | Count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Group with specific characteristics | Ethnic minority group | The National Plan for the Protection and Utilization of Biological Species Resources China Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan (2011–2030) | 3 |

| B | The needy Low-income group | A guideline on ecological and environmental protection helping win the battle against poverty The 14th Five-Year Plan of Action for rural greening | 4 | |

| C | Local people | Residents within the project area Grassroots community Indigenous people | A guideline on establishing a system of protected natural areas with national parks as the main body National park spatial layout scheme | 35 |

| D | Villagers Rural residents Fishermen Herdsmen | The 14th Five-Year Plan of Action for rural greening Strategic Plan for Rural Revitalization (2018–2022) | 20 | |

| E | River chief Lake chief Forest ranger Grassland manager | Opinions on comprehensive implementation of the river chief system Guidelines on the implementation of the lake chief system in lakes Opinions on the comprehensive implementation of the forest chief system | 9 | |

| F | The broader community | Citizens People Society | National Wetland Protection Plan (2022–2030) Plan for the Construction of Major Projects supporting the Ecological Protection and Restoration System (2021–2035) | 82 |

| Pathway | Major Fields (Number of Relevant Policies) | Major Groups (Number of Relevant Policies) |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Biodiversity (16) Water management (16) Rural development (14) | F (49) C (16) D (13) |

| Supervision | Biodiversity (15) Water management (12) Ecological protection (11) | F (40) C (16) D (6), E (6) |

| Participation | Biodiversity (19) Ecological restoration (18) Water management (17) | F (53) C (33) D (14) |

| Knowledge preservation | Rural development (11) Biodiversity (7) Urban development (3) | F (10) D (9) C (6) |

| Knowledge adoption | Biodiversity (9) Rural development (8) Ecological protection (3) | F (10) D (8) C (6) |

| Pathway | Qiandao Lake Water Fund | Snub-Nosed Monkey Protection Network | Laohegou Land Trust Reserve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | River chiefs: In-person participation in interactive educational activities towards community members and downstream citizens Rural dwellers: Experience sharing in farming techniques training sessions | Villagers: Formation of the ecological guide team to lead educational visits to nature reserves for visitors from other cities, as well as report violation activities in a timely manner | |

| Supervision | River chiefs: Regular patrols along local rivers, issue reports, and identification and removal of invasive species by river chiefs Rural dwellers: Adaptative management of nature-based agricultural solutions based on timely feedback | Villagers: Facilitation of area-specific mountainous landscape knowledge to protected area regular patrols and management | |

| Participation | See education, supervision, and knowledge adoption | See supervision, knowledge preservation, and knowledge adoption | See education, supervision, and knowledge adoption Villagers: Development of the eco-friendly rural B&B industry |

| Knowledge preservation | Villagers: Contribution of informal knowledge on species and landscapes to scientific protection method design and implementation Ethnic minority people: Contribution of religious belief and traditional cultures to co-development of community branding, products, and communal space | ||

| Knowledge Adoption | Rural dwellers: Cropland and planting knowledge and skill contribution through consultations to planning and experimenting nature-based agricultural solutions | Forest farm rangers: Provision of expertise in local ecosystems and endangered species in protection species identification and development of adaptative management methods with the scientific expert team Villagers: Contribution of farming and livestock breed knowledge in customized rural product development |

| Government | Qiandao Lake Water Fund | Snub-Nosed Monkey Protection Network | Laohegou Land Trust Reserve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central |

|

|

|

| Provincial |

|

|

|

| Municipal |

|

|

|

| Rural/ Village/ Community |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, R.; Mu, Q. Integration of Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Policy and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions in China: Progress and Highlights. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411104

Yu R, Mu Q. Integration of Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Policy and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions in China: Progress and Highlights. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):11104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411104

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Ruizi, and Quan Mu. 2023. "Integration of Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Policy and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions in China: Progress and Highlights" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 11104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411104

APA StyleYu, R., & Mu, Q. (2023). Integration of Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Policy and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions in China: Progress and Highlights. Sustainability, 15(14), 11104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411104