Abstract

The villages around a Cultural Heritage Site (CHS), despite being influenced by long-term restrictive conservation policies for protecting their heritage’s integrity, are often excluded from heritage recognition. They do, however, have opportunities to develop tourism and become places involving multiple stakeholders to alleviate the tension between cultural heritage conservation and the sustainable development of the village. As a result, the villages around a Cultural Heritage Site have been faced with much more complex situations than the sites themselves, as more stakeholders participate in and invoke the profound transformation of the space. To clarify this complex spatial transformation and bring about sustainable development, Lougetai village around the Chang’an Cultural Heritage Site, one of the heritage-led tourism villages, is taken as a case study to elucidate the spatial mechanism by applying Actor Network Theory. To achieve this, the multiple actors involved in the process of tourism projects and concomitant spatial transformation are investigated based on: (i) an archival study; (ii) participant observation; and (iii) semi-structured interviews. Our findings are as follows: (1) Lougetai village experienced profound spatial transformation into a heritage-led tourism destination, with residential, communication, and production spaces added, together with commercial space; (2) the process of constructing the heritage-led tourism destination included a heterogeneous actor network in which the Weiyang District Government played a vital role in enrolling other actors to participate, including the village committee, professionals, investors, tourists, and local people; (3) in the process of constructing the heritage-led tourism destination, the interests, intentions, and actions of heterogeneous actors can affect the village’s development. This complicated mechanism is identified from a detailed analysis of the implemented strategies and interests of diverse actors. These findings provide an understanding of the process of establishing heritage-led tourism and can be used to support future research in relation to the sustainable development of the villages around a Cultural Heritage Site.

1. Introduction

With rapid urbanization, alleviating the tension between cultural heritage conservation and the development of nearby villages has become increasingly topical. This is particularly imperative in China, in which more than 150 CHSs are located and have been discussed at the forefront of debates on the issues and challenges facing CHSs [1,2,3]. Different from ordinary villages or historic blocks, the villages around a CHS are special. In spite of the cultural relics dotting the landscape in the concomitant villages, a separation is made between the heritage areas and village areas: the villages, in the orbit of cultural heritage, are implicitly and arbitrarily considered ordinary areas without significant cultural meaning [4]. Given the fact that they are often excluded from heritage recognition but are in close proximity to cultural heritage, villages are often considered incompatible with heritage conservation. In this sense, static and simple conservation restrictions on villages were first proposed and implemented in order to protect their heritage. After China had identified the disadvantages of these static restrictions, a feasible pathway for a harmonious relationship between heritage conservation and village development started.

A consensus on developing tourism in the villages around a CHS, among academics, has been considered to alleviate the tension between cultural heritage conservation and village growth. Some villages around a CHS with location advantages and abundant cultural resources have accelerated the heritage-led tourism process. Heritage-led tourism generally relies on the combination of cultural heritage and the transformation of archaeological achievements into cultural industries to generate economic and social benefits. Based on the mutual interaction between the conservation and utilization of cultural heritage, heritage-led tourism provides comprehensive places that integrate sightseeing, leisure, heritage display and experience, and retail to improve local livelihoods and the local environment. The functions of villages have become diversified, from often a single residential function to a multifunctional environment facilitating tourism. In other words, heritage-led tourism contributes to the transformation of a physical space and its social relations. In the process of spatial transformation, a particularly complex set of stakeholders, mainly including local government, capital, professionals, tourists, and local people, become involved in the villages. This multi-scalar nature inevitably introduces multiple perspectives and divergent voices among stakeholders, on which development’s direction may depend [5,6]. This multi-scaled negotiation is evident in the villages, where, to different degrees, different stakeholders are involved in an ongoing debate over questions about tourism development [2,6]. Therefore, villages with heritage-led tourism have become spatial aggregates, accompanied by diverse actors who participate in them.

As the villages increasingly become mixed aggregates, the interactions between the physical space and interwoven actors may determine the villages’ development. Actor Network Theory (ANT), proposed by Bruno Latour, is regarded as an effective toolkit for analyzing spatial reconstruction by connecting the spatial elements and complex actor networks, which is conducive to understanding the underlying mechanism of spatial changes [7]. Through the lens of ANT, the spatial elements and people are entangled through a translation process and contribute to the tourism-scapes in the villages around a CHS.

To identify the spatial transformation and underlying mechanism of changes in the villages around a CHS, this research addresses three key research questions: (1) To what extent has the space transformed? (2) What role do the diverse actors play? (3) What is the underlying mechanism of this space reconstruction? To explore these questions, the intricate process of tourism in the villages around a CHS needs to be analyzed. Taking Lougetai village near the Chang’an CHS as a case study, ANT is adopted in order to illuminate the spatial transformation and actor network. The aim of this research is to reveal the process of spatial transformation in the villages around a CHS and to understand the relationships among diverse actors. This paper starts with reflections on the ANT and explains the research method used to answer the research questions. This is followed by the case study, and the final section summarizes the findings with a discussion and concluding remarks. This paper has theoretical and practical significance that provides a critical insight into cultural heritage conservation and sustainable village growth.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of the Villages around a Cultural Heritage Site

The precise definition of a “Cultural Heritage Site” was confirmed at the UNESCO Convention in 1972 [8]. The Convention stated that a “cultural heritage site is the works of man or the combined works of nature and man, and areas including archaeological sites which are of outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological points of view” [9]. Similarly, in 1976, the Nairobi Proposal suggested that a CHS referred to “any group of buildings, structures and open space including archaeological and palaeontological sites, constituting human settlements in an urban or rural environment” [10]. As such, the concept of a CHS included not only the areas around historic buildings, but also the associated human activities [11]. This was further developed in 1981, when the Burra Charter considered that a CHS “includes a group of buildings, building or other work, or other works together with pertinent contents and surroundings” [12]. Similarly, in 1985, the Council of Europe Convention proposed that a CHS “is the combined works of man and nature, being areas which are partially built upon and sufficiently distinctive and homogeneous to be topographically definable and are of conspicuous historical, archaeological, artistic, scientific, social or technical interest” [13].

In addition, some scholars have proposed different definitions for a CHS. According to Poulios, a CHS includes ruins with high cultural value in a certain area where tangible forms such as buildings are almost destroyed [14]. Additionally, a CHS should contain historic buildings, important archaeological tombs, and hundreds of sites, as well as monumental sculptures or paintings [15]. According to Fletcher, a place where humans lived and used the land in a way that shows their culture can be considered as a CHS, especially if the area is affected by irreversible change [16]. Also, a CHS is defined as a geographic area associated with a historic event or activity and contains anthropological landmarks or archaeological items [17]. Drawing upon these previous interpretations, it can be argued that a CHS will display an remarkable exchange of human values or human creativity over a long period, together with evidence of history or a civilization that has disappeared or is still present.

Since 2000, the concept of a CHS in China has been changed and developed to make it more localized. Meng believes that a CHS is not only a collection of large ancient sites or ancient tombs, but that it also includes sites related to the geographical environment that contain relics and buildings, forming a complete embodiment of culture [18]. Yu illustrates that a CHS is not an academic concept of archaeology but describes the characteristics of a wide distribution of cultural relics. This refers to sites with a large scope, a wide area, and high value compared with general Cultural Heritage Sites [19]. The ancient capital, original settlements, palaces, mausoleums, religious sites, traffic facilities, water conservancy facilities, handicrafts, and military facilities that occupy important political, cultural, and economic places in China’s history can all be regarded as CHSs [19]. In the symposium on the protection of Chinese Cultural Heritage Sites held in July 2007, the definition of a CHS was the primary topic. Indeed, Fu suggested that a CHS refers to an ancient archaeological site with a prominent scale and value in Chinese cultural heritage, representing a comprehensive system composed of relics and associated environments [20]. In defining a CHS, Zhang emphasizes that large-scale and outstanding value are important characteristics [21].

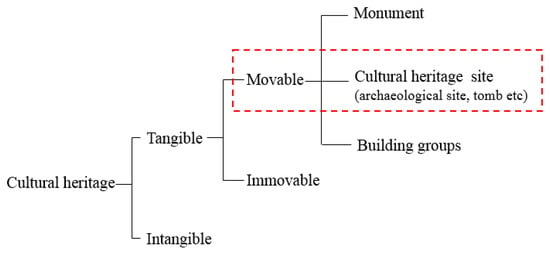

In recent years, in addition to the common feature of a larger scale, some Chinese scholars have defined the concept of a CHS from the perspective of cultural value. Yu believes that a CHS comprises the remains of activities with economic, social, and cultural value left by ancient people, which represent fragments of civilization and carriers of culture [22]. He also suggests that these are sites that have lost their original function and are seen more as a cultural phenomenon of extinction or a representation of history [22]. According to Li, under the concept of cultural heritage, a CHS should fall under the categories of tangible cultural heritage and immovable cultural heritage, and a CHS exists more as a cultural phenomenon or a representation of history owing to the loss of its original function, from the point of view of the protected status of the immovable object [23]. Consequently, from the perspective of scale and value, a CHS refers to a collection of large-scale archaeological sites and ancient tombs of historical importance, which are characterized by abundant relics and important historical information (Figure 1). Compared to individual buildings, a CHS has a distinct regional characteristic, and is composed of relics and related environments.

Figure 1.

The category of cultural heritage (source: the authors).

The nearby villages around a CHS can broadly be defined as the surrounding rural community that coexists around the site [2]. The reasons for the original formation of residential areas vary depending on the type of CHS. Indeed, for example, the residential areas around tomb heritage sites originally developed from the gathering of tomb guardians at ancient capital sites, with the residential areas officially assigned by the state as settlements. Also, for traditional handicraft heritage sites, residential areas were occupied by people undertaking handicrafts [2,19]. While the reasons for the formation of villages are different for each type of CHS, their main functions are consistently food production and housing. Nevertheless, a notable distinct feature Chinese CHSs is their vulnerability and destructibility, which are often the result of the construction materials used for the buildings. With these buildings mainly composed of earth and wood, countless extreme weather conditions, geological disasters, and wars during the changing dynasties have damaged the integrity of much of the original cultural heritage, leading it to gradually collapse, erode, and become buried [22]. In such a context, accompanied by these historical processes, the surrounding villages have also gone through periods of change. From their initial formation and gradual evolution, the relationships between cultural heritage and residential areas have experienced various stages of coexistence and encroachment, partly or completely overlapping, over thousands of years. As a result, a CHS exists in the form of cultural ruins and monuments dotting the landscape amongst rural communities [4].

During the 20th century, a hierarchy of heritage and non-heritage spaces was politically and culturally produced. The heritage spaces have been infused with outstanding cultural value, whereas the concomitant villages have ended up on the periphery of the CHS and are excluded from heritage recognition [4]. This is why the neologism of non-heritage can be applied. Heritage spaces comprise ancient monuments and are subject to government conservation policies and approaches; non-heritage spaces refer to the concomitant villages, which are deemed ordinary spaces [4]. Although cultural ruins and monuments share a similar landscape with the villages, non-heritage spaces consisting of rural communities are still regarded as places whose value is undermined [4,23]. Excluded from heritage recognition but in the orbit of heritage, non-heritage spaces, namely, the villages, including hydraulic and transport infrastructures, and rural settlements, are marginalized [4,24,25]. Deemed relatively meaningless areas, these villages are seen as incompatible with heritage conservation [25]. Thus, the villages have experienced a profound space transformation because of the politically and culturally constructed tension between cultural heritage conservation and the desire for village development.

2.2. Previous Studies on the Development of Villages around a CHS

With unprecedented growth in the past few decades, heritage is often connected with villages as an economic development engine, which can be self-evidently symbiotic and potentially attractive [5]. As such, heritage can be seen as a key economic resource for revitalizing villages. In recent years, much research has endeavored to find a way to achieve a harmonious future for the conservation of CHSs and the sustainable development of concomitant villages. As a result, several methods have been acknowledged for their positive outcomes.

Firstly, heritage-led physical intervention can be implemented by focusing on the adaptive reuse of historic monuments and the further improvement of infrastructure. This has been considered an effective strategy for launching new functions and new opportunities for villages, whilst protecting historical monuments and introducing more economic opportunities for local communities [19]. For instance, a site museum was built alongside Yin Xu CHS and used to display various archaeological resources, such as oracle bones and bronze vessels [26]. Subsequently, many restaurants, shops, and upgraded public infrastructure emerged around the museum, thereby improving employment opportunities and living conditions for inhabitants. In addition, landscape parks and historical parks in China have played important roles [27]. Where CHSs have been protected by large-scale greening, the ecological environment has also been improved and often provides new leisure and entertainment spaces for residents in the villages [28]. Cui Ming proposed the creation of a comprehensive cultural park that integrates museums, green spaces, and public places, which not only enhances the environment of the villages, but also provides places for recreation, fitness, and leisure [29].

Secondly, alongside the adaptive reuse of heritage, other heritage-led physical interventions can include the upgrading of village industries. Unlike the adaptive reuse of historic monuments that emphasizes their heritage value, upgraded industries pay more attention to guaranteeing future employment opportunities for the local population. Developing comprehensive cultural districts is a common way of upgrading industries. A comprehensive cultural district generally relies on the combination of different aspects of cultural heritage, transforming archaeological achievements into cultural industries to generate economic and social benefits [2]. A comprehensive cultural district has been described as a process of synergetic integration among the several subsystems of a CHS. These subsystems involve the conservation and utilization of cultural heritage, and the improvement of environmental conditions and the livelihoods of inhabitants, in order to achieve a sustainable outcome. Upgraded industries aim to break the dualism of conservation and livelihood, by respecting the living dimension of the area. Based on mutual promotion, Zhu and Quan identify how the comprehensive cultural district implemented in the Du CHS succeeded in improving living conditions and creating an attractive environment for local people [30]. In addition, residents can benefit from cultural industry through activities such as the operation of local tourist accommodation, creating and selling products, and developing agriculture for cultural sightseeing [19].

The villages in close proximity to heritage sites can therefore be stimulated to create and develop economic value, and to meet local communities’ needs by creating jobs and improving income while maintaining a strong link with cultural heritage. However, although these heritage-led interventions have provided ways of alleviating the tension between cultural heritage conservation and sustainable village development, these physical interventions often tend to regard the village as being in a static state.

2.3. Issues of the Villages around a CHS

Since the tension between cultural heritage conservation and sustainable village development needs to be addressed, reuse to suit tourism-based adaptations has to be on the agenda [31]. Cultural heritage has to be regarded as a facilitator of the local economy rather than as a barrier to development. Villages with a distinctive heritage tend to favor tourism awareness because of the irreplaceable localization ingrained in the resource of cultural heritage.

Although tourism is regarded as having a compatible symbiotic relationship with village development, how this coordination can be achieved remains contested [3]. While heritage-led tourism with local uniqueness can transform the villages into livable places, a particularly complex set of stakeholders are involved in the villages. Subsequent multi-scaled negotiations are evident in villages with different stakeholders involved in ongoing debates over the most appropriate form of village tourism development [2,6].

The villages, as discussed before, are characterized by disputes among multiple stakeholders, who represent diverse and sometimes conflicting interests. Given this intricacy, the villages around a CHS can be regarded as complex. In recognition of the multiple users of and often conflicting intentions in villages with heritage-led tourism, a paradigm is proposed whereby conflicts amongst stakeholders are mediated by reaching a consensus-building process with the consideration of both spatial and temporal factors. In other words, by engaging stakeholders, a holistic understanding of the problem can be developed and common targets applied in order to negotiate a shared future vision [32,33]. Thus, two primary themes stand out as pertinent from the inquiries into how tourism might be created and used to promote long-term development.

Firstly, whilst many studies tend to focus on specific space design and the planning of villages around a CHS to alleviate the tension between conservation and village development, they also simplify the complexity of space as a physical and static “container”. In this sense, the villages around a CHS are treated as a product that follows an established pathway. However, the development of villages around a CHS is a process, with development not only being subject to diverse stakeholders but also evolving over time. The connotation of space also has changed. It is not static and purely physical; instead, the space is constructed by the stakeholders. The process of constructing tourism is, to some extent, related to mutual interactions between the stakeholders and the space. Secondly, after considering the spatial and temporal factors of space, the interdependence of stakeholder groups may be unfolded in terms of their roles, motivations, and mutual relationships. This study will articulate the comprehensive process of stakeholders by analyzing the divergent voices and social networks in the process of constructing tourism. This will enable a deeper understanding of the essence of this process and the challenges that arise when villages are faced with miscellaneous and profound space transformation, and therefore, inform future sustainable improvements [33].

3. Materials and Methods

This section will introduce Actor Network Theory (ANT) and how this can be applied to this research, and build upon the data collected through archival studies, semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders (government officials, investors, architects, planners, tourists, and local people) in Lougetai village around the Chang’an CHS, and on-site participant observation and documentation.

3.1. Study Theory—Actor Network Theory

ANT, also called the sociology of translation, argues that everything in society and the natural world involves constantly changing relationships. In this sense, its methodology is committed to describing and analyzing the complex heterogeneous relationships and interactions amongst entities in certain processes [34]. ANT comprises three pivotal components: the recognition of actors; translation; and a heterogeneous actor network [7,35]. An actor is an individual entity that can take action and exert influence on the others. According to the general symmetry principle, actors include not only humans but also policies, funds, land, housing, etc. Translation plays a core role and is a process in which the associated actors negotiate and make adjustments over time [36]. This consists of problematization, interessement, enrollment, and mobilization. Specifically, problematization refers to the problems encountered in the process of achieving the targets, interests, preferences, and demands. Interessement embraces a group of actors that can stabilize the alliance of interests by binding the other actors [37]. For interessement to be successful, enrollment cannot be overlooked. Enrollment is a series of “negotiations trials of strength and tricks that accompany the interessements and enable them to succeed” [36] (p. 211). Enrollment is a successful interessement. After enrollment, the actors are mobilized and assigned corresponding responsibilities. Under ANT, the human and non-human actors jointly form a heterogeneous network, which is a dynamic and never-definitive network. The key to understanding the phenomena that occur in society and the natural world lies in the dynamic changes and associations in the network.

The reasons why ANT is used as an overarching theory in this research are as follows. Firstly, as mentioned, whilst these studies tend to focus on specific space design and the planning of villages around a CHS to alleviate the tension between conservation and village development, they also simplify the complexity of village development. This includes political, economic, and social actors. In this sense, the development of villages around a CHS is a process, because its development is not only subject to diverse actors (as presented in the case study of Chang’an CHS in this research) but also evolves over time. Secondly, although these specific space designs and the planning of villages are set-out by the government, investors, professionals, local people, etc., their roles, motivations, and mutual relationships have not been fully unfolded. The development of villages may therefore be embedded in a wider context in which the governmental policies and plans, capital input, technical guidance, and responses from local people play decisive roles in determining its direction. Thus, a deeper understanding of space changes, a dynamic perspective, and related stakeholders are extracted as parameters that form a departure point for the holistic, dynamic, and critical examination of villages, whilst adopting a time-scale to explore processes that integrate space changes and the mechanisms of the stakeholders. Furthermore, the research method will naturally be extracted based on a qualitative paradigm, as it is argued that the space transformation of villages around a CHS involves multiple realities that consist of diverse roles. The discussion and results will be presented through an understanding of the underlying mechanisms behind the space transformation of villages around a CHS throughout time, so as to better alleviate the contradiction between conservation and development.

3.2. ANT in the Context of Villages around a CHS

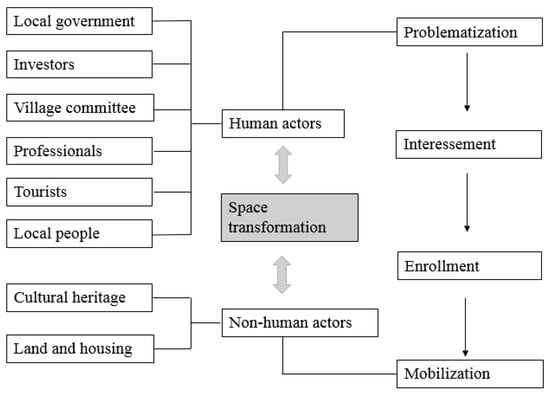

An actor is an individual entity that can take action and exert influence on others, and includes human and non-human entities. In the context of CHS, human actors can be broadly defined as those who can control tourism projects and have a stake in tourism. In this sense, local governments with administrative power, investors who have capital power, professionals who provide technical guidance, village committees who are in charge of tourism, tourists who consume village heritage resources, and local people who take part in day-to-day engagement with the village are selected as human actors. Non-human actors are resources that can be utilized and controlled by human actors. From this perspective, the cultural heritage, land, and housing that belong to the villages around a CHS are regarded as non-human actors.

Translation plays a core role and is a process by which the associated actors negotiate and make adjustments over time [36]. The human actors and non-human actors are interwoven, and therefore, co-decide the development direction of the villages. The translation process comprises problematization, interessement, enrollment, and mobilization. In the processes of problematization and interessement, the appeals, preferences, and demands of the actors are different. The local government, investors, professionals, village committee, tourists, and local people, as well as the non-human actors, have their own problems and interests related to the villages around a CHS. As long as the presented problems are solved, the actors’ immediate interests are expected to be fulfilled. In the process of enrollment and mobilization, these actors need to translate interests into actions in order to address any problems. The local government, investors, professionals, village committee, tourists, and local people, as well as the non-human actors, are assigned different roles: policies, funding, and planning are assigned to the local government; capital input is assigned to investors; and design is assigned to professionals. Meanwhile, land and housing, which tend to be the greatest concerns of the village committee and local people, can be regarded as non-human actors. Based on a shared vision and stabilized characteristics, all the actors join the network and become representative spokespeople (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The applied ANT in the context of villages around a CHS.

As Bansal and Knox-Hayes (2013) and Whiteman and Kennedy (2017) argue: “In a sustainability journey, time must be seen as lines of becoming or transformations, and space must be seen as arenas of interactions” [38,39]. When these human and non-human actors leverage their strength and influence each other, the space transformation will be influenced by political, economic, and social actors. In order to cover all types of space, the spaces of villages around a CHS include residential space, communication space, and production space. As space transformation is the reconstruction of multiple actors representing different intentions, and the processes of different actors’ goals echoing the logic of the actions implies the interweaving of relationships. In association with translation, the residential space, communication space, and production space accommodate different actors and present different actor relationships, so as to adapt to the needs of tourism.

Based the analysis above, how ANT can be applied to the villages around a CHS can be clarified. Indeed, the recognition of actors, translation, and heterogeneous actor networks signifies that all actors (human and non-human) with their heterogeneity, the evolution of time, and influence upon space are essential. Again, the sustainability of village development is viewed as a process where temporal, spatial, and relational dimensions are important. Thus, this paper upholds that space transformation and relationship analysis is relevant to the study of sustainable solutions for villages around a CHS.

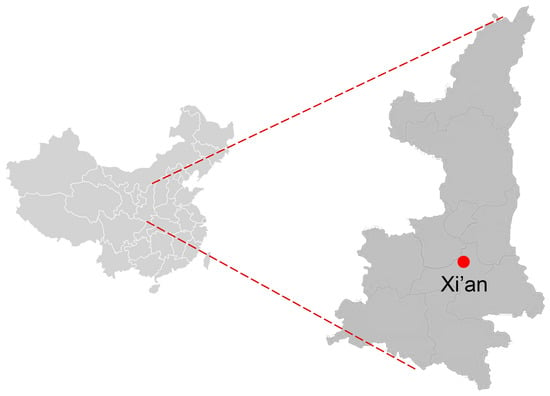

3.3. Study Site: The Lougetai Village around Chang’an CHS

The study site of this research is Lougetai village around the Chang’an CHS in Xi’an City, China (Figure 3). The Chang’an CHS is one of the largest CHSs in China and accommodates 45 villages in total. The Chang’an CHS has been the central locus of development practice in concomitant villages and has witnessed diverse initiatives, which provide a rich database for this research. Lougetai village, one of the heritage-led tourism villages around the Chang’an CHS, has experienced a relatively mature stage of tourism construction and was therefore selected for this analysis of its space transformation and actor network.

Figure 3.

The location of Xi’an in China (source: the authors).

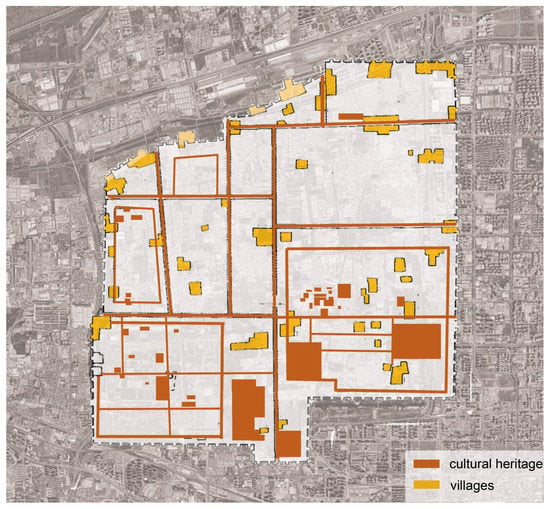

The Chang’an CHS, built at the beginning of the Han Dynasty, is located northwest of Xi’an. With an area of 37 square kilometers, it is one of the largest CHSs in China [40,41]. The formation of the Chang’an CHS can be traced back to the reign of Liu Bang in the Western Han Dynasty around 200 BC, when Liu Bang’s (Liu Bang (247 BC–195 BC) was the founding emperor of the Han Dynasty) important official—Xiao He—proposed and supervised the construction of royal palaces to represent the supreme status of the emperor [42]. It was the first ancient capital with a complete layout in Chinese history and was amongst the largest in the world at that time, comparable to Rome, Italy [41]. Changle Palace, Weiyang Palace, and Jianzhang Palace are the three most famous palaces in the Chang’an CHS. After its construction, the emperors of the Western Han Dynasty worked and lived here, and it became the center of government for more than 200 years during the time of the Han Empire [42]. Around BD 139, an official named Zhang Qian visited the Western Regions from Weiyang Palace and started the ancient Silk Road [43,44]. The Silk Road facilitated political, economic, and cultural contact by linking the Western Han Dynasty with many countries. Around 8 AD, after the fall of the Western Han Dynasty, a total of eleven subsequent empires were established in Chang’an CHS as the capital until the establishment of the Sui Dynasty [44]. Whilst Daxing city was constructed as the capital at the beginning of the Sui Dynasty, the Chang’an CHS was delimited as a royal forbidden area for hundreds of years [44]. During the Ming Dynasty, the Chang’an CHS was reused as a military base to accommodate army villages. From then to modern times, more villages with civilian populations have been constructed in the area. As the Chang’an CHS emerged, expanded, and declined, successive construction activities, war, and natural disasters destroyed the integrity of its cultural heritage. Consequently, after the founding of the PRC, the Chang’an CHS, including the concomitant villages, was listed as one of the National Key Cultural Heritage Conservation Units in March 1961 (Guojia Zhongdian Wenwu Baohu Danwei) [2]. With a history of over 2000 years, the Chang’an CHS has nurtured a rich culture and now includes 45 villages and around 200,000 residents (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Master plan for Chang’an CHS (source: the authors).

To reconcile the tension between heritage conservation and the development of the villages, the Chang’an CHS entered a new stage of development in 2000 with a new agenda of village development. Since then, a series of plans and policies have been promulgated and implemented. Indeed, cultural regeneration has led to the development of the villages around the Chang’an CHS, and space transformation has become the main aim of the villages.

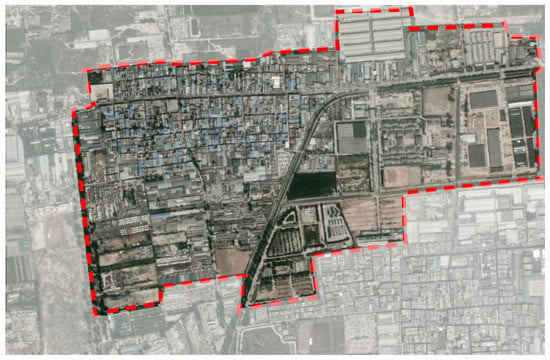

Lougetai is a typical village around the Chang’an CHS, with 20,000 residents (Figure 5). Since it was recognized as part of the tourism industry, heritage-led tourism was launched as a prelude to village development. Heritage-led tourism can be defined as “a process triggered and supported by a wide range of cultural catalysts that could realize the revitalization” [45,46]. Against these backdrops, Lougetai village, located adjacent to a legacy of archaeological and historic heritage, has received renewed interests in recent years due to its economic value. The aim of the tourism project has been to transform Lougetai village into a tourism destination by capturing the positive externalities of its heritage. The implemented tourism plans have generated a new landscape and supported local commercial activities, such as tourism-related services and retail facilities.

Figure 5.

Site plan for Lougetai village (source: Google Maps).

3.4. Research Methods

This research adopts a qualitative approach including an archival study, semi-structured interviews, and participant observation. Firstly, between 2020 to 2022, data related to the case study and representative stakeholders were collected from papers, media reports, official government files and reports, and books, to gain a holistic understanding of the case. From 2021 to 2022, semi-structured interviews were carried out to investigate the views of and interconnections between the various stakeholders. The interviewees were three government officials and cadres of Weiyang District People’s Government, two spokespersons of Xuanping Cultural Development Ltd., as well as two architects and planners of local institutes, ten tourists, and seven local people (Table 1). The semi-structured interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes and were recorded with permission from the interviewees. Furthermore, participant observations were conducted in this research to investigate the physical space changes.

Table 1.

Interview details informed by ANT (source: the authors).

Specifically, the interviews started with two cadres from Weiyang District People’s Government, who were the heads in charge of the heritage-led tourism of villages around the Chang’an CHS. The third was a cadre from Hancheng Subdistrict Office responsible for guaranteeing that newly built projects were harmonious with heritage relics. Three village leaders from Lougetai village who were direct participators were also interviewed. The information from these interviews helped to tease out the policy formation and delivery process; the rationale underlying the policies; the process of developing heritage-led tourism; perceptions of the tourism; and the village leaders’ potential motivations. The interviews with the local government officials were further supplemented by two interviews with representatives from a private capital organization, namely, Xuanping Cultural Development Ltd in Xi’an, China. Interviews with their representatives further shed light on the specially adopted strategies to facilitate the tourism boom. The following professional interviewees were introduced by the investors, as the investors were able to identify and recruit additional key informants whilst building mutual trust with the interviewer. Interviews with professionals focused on their specific design approaches to tourism projects. These interviews contributed to understanding the process of developing heritage-led tourism in Lougetai village. In addition, ten tourists and seven local residents were interviewed. The tourists were able to describe their experiences and perceptions of tourism, and the local people were able to articulate their strategies to adapt to life alongside tourism.

4. Results

Lougetai village has experienced a profound space transformation from a traditional village to a heritage-led tourism destination. Previously, Lougetai was a residential village with a dilapidated environment that focused on production as its main economic function. The arrival of heritage-led tourism brought about improved living conditions and new infrastructure. ANT was used to elaborate this process of change as follows.

4.1. Recognition of Different Actors

As ANT indicates, the actors include both human and non-human entities. The identification of actors can be complicated as the potential actors are diverse. During our fieldwork, the human actors were recognized as the Weiyang District People’s government, the Lougetai village committee, Xuanping Cultural Development Ltd., as well as the architects and planners of local institutes, tourists, and the local people. The non-human actors in Lougetai are its cultural heritage, land, housing, administrative policies, and funds, etc. Together, these actors are a representative model of stakeholder groups in heritage tourism. All of these actors are actively involved in the project and may positively or negatively affect the project [47]. After teasing out the related actors, it was important to further identify how their appeals, preferences, and demands are integrated into the actor network through translation.

4.2. Translation Process

The translation process comprises problematization, interessement, enrollment, and mobilization. These parts are intertwined and consist of a “mish-mash of all sorts of decisions” [48]. However, each of them constitutes progression in the negotiations between the actors. In relation to Lougetai village, the four parts can be explained as follows.

4.2.1. Problematization and Interessement

In the process of heritage-led tourism, the appeals, preferences, and demands of actors are different. For the local government, economic growth was of the greatest concern. Although the integrity of cultural heritage benefited, the local government still displayed a pro-tax tendency. Such a dual role is particularly evident in the local government and its strategic plans, in which they have expressed a desire to include cultural heritage resources as a key part of the city’s economic development. One of the government leaders of Weiyang District People’s Government said: “For local government, the cultural heritage conservation is a burden. We have to pour a lot of money into daily conservation, but the financial revenue is limited. As the economic development has been backward, tourism was regarded as a solution to the current situation”.

For the Lougetai village committee, a better living environment and public infrastructure were strongly anticipated because the long-term conservation regulations of cultural heritage had imposed many restrictions on village development. One of the village leaders mentioned the importance of cultural heritage conservation, but he tended to favor tourism activities as a solution to improving their livelihoods and was less interested in the importance of conservation when faced with long-term poverty. As the village committee is the lowest level of the bureaucratic system in China, village development has, to a large extent, to depend on financial support from the upper government. The village leaders shared their views on the tourism projects, saying that: “As the long-term conservation deprived us of normal life, we had to find a way to improve the local environment by launching tourism projects, but the problem lay in the lack of financial support”.

For the private sector, seeking maximum profits was always deemed as a priority. Due to the limited public finances of the local government, achieving heritage-led tourism in the villages around the Chang’an CHS requires investment from the private sector. In this regard, attracting private capital is a crucial component of successful village development. Not all private investors are interested in making such an investment due to concerns over the impact of conservation constraints on capital accumulation. Therefore, some affluent enterprises from outside have been targeted in order to inject significant funds into tourism projects.

For tourists, the villages around the Chang’an CHS provided an opportunity to enjoy the cultural heritage. Many tourists expressed a strong preference for heritage authenticity and hoped to enjoy the cultural atmosphere in the villages. At the same time, some tourists also held the view that the villages had the potential to become fantastic site that are integrated with modern consumption in order to cater to younger generations. For tourists, a desire for locations that can offer tourism activities in an appealing environment with excellent accessibility has emerged.

Professionals, including architects and planners, can directly control spaces through their professional actions and design strategies for tourism villages. According to the interviews, an area-based approach was adopted as a property-led village redevelopment was considered less sustainable and received much criticism. As one architect said: “The former property-led scheme of development was proved to be less sustainable. As professionals, we need to balance multifaced interests and avoid pure profit-oriented results”.

The main problem emphasized by the local people was their living quality. Indeed, all of the local people who were interviewed expressed strong dissatisfaction with the local environment and low income. According to the survey, the average income of the local people in the villages around the Chang’an CHS is much lower than in the surrounding built-up areas, and therefore, local people are eager for a higher-quality living environments and improved income opportunities.

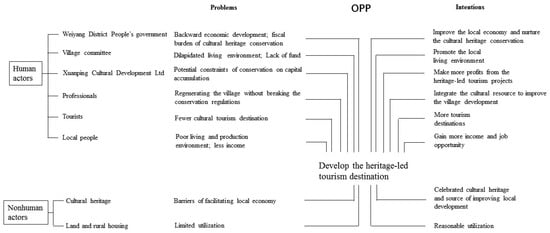

All of these actors have their own immediate interests and problems. As long as the presented problems are solved, the actors’ immediate interests are expected to be fulfilled. In this sense, to solve their problems and to satisfy their interests, the actors are aggregated into obligatory passage points (OPP) and form an alliance (Figure 6). At the beginning of translation, each actor’s problems and demands are integrated into the OPP. They attempt to solve their problems and satisfy their interests. At the same time, all the actors need to arrive at the same goal, namely, the development of heritage-led tourism in Lougetai village.

Figure 6.

Problematization and interessement of human and non-human actors (source: the authors).

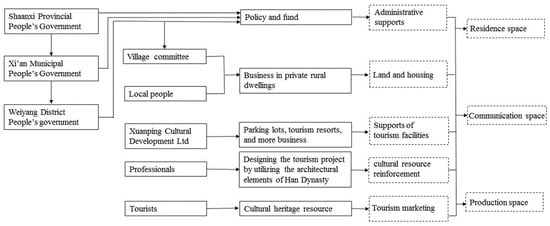

4.2.2. Enrollment and Mobilization

After clarifying the related actors and their immediate interests, the following section focuses on how to translate their interests into actions and to dispel their problems. In the process of transformation to heritage-led tourism, the heterogeneous actors perform a series of strategies for enrollment. The Weiyang District People’s government, the Lougetai village committee, Xuanping Cultural Development Ltd in Xi’an City, the architects and planners of local design institutes, tourists, and local people negotiate with each other to form an alliance (Figure 7). These heterogeneous actors are then able to exert their powers. Enrollment and mobilization include the following main categories.

Figure 7.

Enrollment and mobilization of actor network (source: the authors).

Administrative policy and funding: Given the criticism of the property-led scheme (i.e., relocation of the village around the Chang’an CHS), the local government turned to an “area-based” approach. In doing so, they formulated a comprehensive scheme to balance the economic, social, and cultural aspects, in response to a holistic development policy for preserving the site’s authentic historical features and improving the rural economy, livelihoods, environmental quality, and infrastructure from Shaanxi Provincial Government and Xi’an Municipal Government. Meanwhile, special funds supported by the upper government were allocated to Weiyang District Government to encourage a series of preliminary preparations. To launch the tourism projects, special funding was provided to improve a wide range of public infrastructure, including the maintenance of drainage and sewage piping, roads, and pavements, and the installation of gas pipelines and underground electric cables. The previously open drainage on both sides of the streets was also improved and upgraded to underground pipes. In terms of heating, gas, and power supplies, the villages were also integrated into the municipal system.

Support of tourism facilities: In the case of Lougetai village, Weiyang District government delivered a package of physical environment work to improve the village’s economic value, and in return, investors undertook tasks such as constructing tourism facilities. Given the intrinsic pursuit of more profits, private actors had to maximize their profits by associating the heritage site with capital accumulation. At the behest of investors, the professionals proposed high-platform buildings, courtyard buildings, and pavilions that adopted the architectural forms of the Han Dynasty in order to highlight the cultural charm of Lougetai village. Moreover, other infrastructure projects were completed, such as food stalls, signboards, and parking lots, to facilitate the tourism projects. The introduction of new commercial activities further catered to the creation of a tourism village. In Lougetai village, further business types have been introduced, including catering, leisure and entertainment, and retail. In order to ensure profits, selected businesses are evaluated every month, and underperforming and unqualified businesses are excluded.

Technical guidance for cultural resource reinforcement: Professional teams were commissioned to undertake the design and planning of tourism projects. The professionals’ space strategies mainly involved employing the architectural forms of the Han Dynasty and integrating modern commercial elements. They employed cultural symbols with the intention of emphasizing distinct village branding and creating a cultural narrative. Indeed, the application of architectural features from the Han Dynasty to tourism projects was intended to highlight the cultural features of the villages. Additionally, the collage of modern commercial elements was conducive to achieving profits as it fulfilled tourists’ commercial needs. As a result, tourists can see the typical pseudo-architecture with yellow beams and red columns (the colors that were most used in the palaces and official buildings of the Han Dynasty) decorated with modern glass and the signs of chain-brands. The display of various brands was one of the design strategies used to create a space that delivers a commercial experience, because these brands are the most convincing elements and are representative of the intention to create a novel consumer experience, especially for younger generations.

Land and rural housing utilization: As a direct participator in the village’s development, and benefitting from the support of Weiyang District People’s Government, the Lougetai village committee devoted itself to engaging in tourism projects. In doing so, they provided assistance for community residents to operate businesses that improved the local environment. With the help of the village committee, some residents have tended to put more emphasis on exchange value and attempted to use available resources for profits, such as renovating and renting out their rural dwellings. Thus, local tourism souvenir shops, B&Bs, and restaurants have flourished in the surroundings of tourism areas, and local people have gained more income and business opportunities in the process of tourism development. For instance, the interviews with restaurant and hotel owners in Lougetai village revealed that rents had doubled since 2015: “The current residential rent is 7 yuan per square meter per month. For a 30 square meter shop, the amount is 6300 yuan per month”. The increasing rent has become an alternative source of income for local people. Also, during this research, it was found that many private dwellings have also been renovated to reflect the culture of the Han Dynasty in order to attract tourists. When asked about the reasons for this, one of the residents said: “I would like to make it more Han cultural style, because it can represent my place. I think when urban travellers come here, they would like to see the villages full of traditional culture”.

Tourism marketing: The local government and investors promoted the village brand through diverse media, such as the Internet, which has attracted more tourists who want to experience the simple village’s traditional culture after experiencing the massive industrialization in the city. The popularity of tourism also brought about ‘home-returning’ since many local people who had previously sought jobs in the city have realized that there are now more opportunities in the village.

Consequently, in the process of translation, it was found that the local government’s administrative power played a vital role. As a dominant actor, the local government can give other actors top-down support and form a stable action network. The local government mobilized private capital, such as the Xuanping Cultural Development Ltd in Xi’an City, to participate and provide the financial support needed to proceed with the heritage-led tourism projects. This, as argued, was inevitable given the emergence of entrepreneurship in Chinese cities, where local governments increasingly collaborate with capital interests to increase revenue and profit [49]. As the most stable network, local government and capital are able to play a decisive role, whilst at the same time, other heterogeneous actors play a role in the actor network. Professionals, including planners and architects, are responsible for materializing the cultural elements by controlling the design and creation of physical space. The village spaces are often reconstructed to reflect historical and cultural elements with regional characteristics as an important means of generating commercial profits. Driven by the commercialized environment, the local people followed suit and actively renovated their private dwellings in line with the culture of the Han Dynasty in order to attract tourists. Regarding the space reconstruction of tourism destinations, heterogeneous actors paved the way through administrative policies and funding, support for tourism facilities, cultural resource reinforcement, land and rural housing utilization, and tourism marketing to provide conditions conducive to the creation of a tourism destination. Through this transformation into a heritage-led tourism destination, parts of the residential space, communication space, and production space have been reconstructed and upgraded to commercial spaces through the implementation of the tourism development strategy.

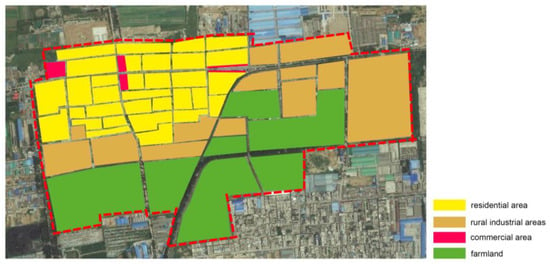

4.3. The Space Results of ANT Translation

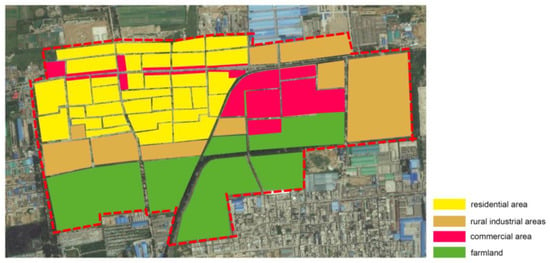

Following the heritage-led tourism strategy, Lougetai village has experienced profound space transformation and accompanying changes in social relationships. Previously, restricted by the regulations of cultural heritage conservation, the land use structure in Lougetai village was relatively mono-functional (Figure 8). It mainly consisted of agricultural land augmented by some construction land. The introduction of tourism has resulted in more land being devoted to business activities and a coinciding decrease in agricultural land (Figure 9). The following section will analyze this process by examining the physical space transformation as well as the changes in the accompanying social relationships.

Figure 8.

Land use before tourism (source: the authors).

Figure 9.

Land use after tourism (source: the authors).

4.3.1. Physical Space Changes

The three main categories of rural land use (residential, communication, and production space) have experienced the addition of commercial space. The connotation of space has gone beyond the mere physical function and embraced social space with more complex social relationships.

Residential Space

The change from traditional villages to cultural tourism quarters has provided a commercialized environment and encouraged residents to renovate their residential spaces to create more profits. Benefitting from tourism development, many local people have converted their rural dwellings into special tourist facilities such as B&Bs, cultural workshops, and restaurants. In doing so, the layout and interior functions of the buildings have experienced profound changes.

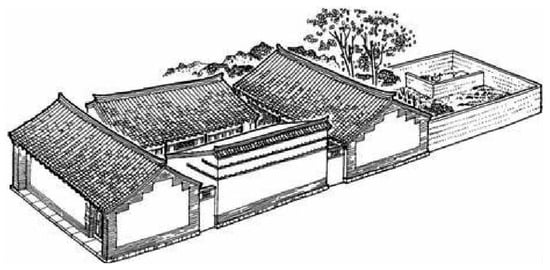

The typical layout of a traditional rural dwelling in Xi’an was characterized by a shading wall at the entrance, the main house in the middle, and wing houses on the two sides. The main house had a double sloping roof and was generally three-roomed, with the middle room as the main space centered on family activities including eating, chatting, and holding ceremonies, with its door facing the garden. The bedrooms were on the two sides, with the inside doors facing the middle room. Wing houses were more special, as they had a “half-built sloping roof (the half-built sloping roof is a special type of dwelling in Xi’an)” (Figure 10). The reason for this, first of all, was that the rain could flow into the self-owned courtyard. Moreover, the “half-built sloping roof” could be connected to the neighbors’ houses so as to share a common wall. This not only saved on building materials, but also turned the external wall into an internal wall, which reduced heating requirements in winter. After the influx of tourists to the villages, as more demand for space was created, some rural dwellings were rebuilt to provide rooms for the increasing number of tourists and to generate additional income. The most obvious change was the transformation of the “half-built sloping roof”, with its distinct characteristics, into a flat roof (Figure 11). The obvious advantages of a flat roof is that it can be built from very simple materials in a short time, and more storeys can be added if needed for hotels, B&Bs, and restaurants to accommodate the tourists.

Figure 10.

The former traditional rural dwellings [50].

Figure 11.

The current rural dwelling partly transformed into grocery stores and restaurants (i.e., China Mobile Limited, Noodles Restaurant shown in the figure) alongside the main street (source: the authors).

In addition to the layout changes, changes in the buildings’ interior functions completed the tourist-centered shift. The central room used to be strictly symmetrical, that is, the types, quantities, shapes, and materials of the furniture were the same or similar and were displayed along the central axis. In the middle of the central room, paintings or calligraphy were set against the wall, and a table was put in front, on which memorial tablets and porcelain were placed. Chairs and tea tables were placed on both sides along the middle axis of the central room. However, with cultural tourism growing, the original functions centered on family activities have been replaced by business functions centered on tourists, such as tourist receptions and exhibitions of Chang’an culture. To attract tourists, many local people have created a special cultural atmosphere to make their central rooms popular online with celebrities and attract customers by combining Chang’an culture with modern-style furniture. For example, during his on-site research, Mr. Xia used a large area of solid neutral color and a matching simple log dining table, coffee table, and lounge chair to create a popular Scandinavian style (a popular online celebrity decoration style in China). Chang’an cultural elements were then interspersed throughout the room. He also sacrificed the function of the central room as a family space in order to expand the tourist reception area. Xia’s example is not rare in Lougetai village and the transformation to tourism-focused activity has led to many others transforming their central rooms into commercial spaces to attract consumers.

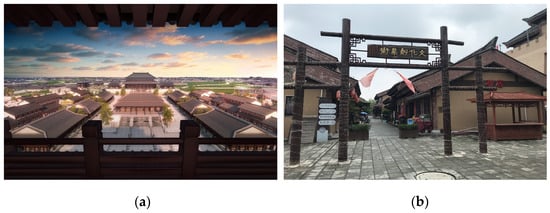

Communication Space

The most dramatic transformation of Lougetai village has seen the integration of numerous trendy shops to target the tourism market. Tourism enclaves are a product of the immature stage of tourism development and in Lougetai, and there are some enclosed tourism enclaves segregated from the surrounding rural environment. Regardless of holistic rural planning, the selection of tourism locations was often random, so these enclaves presented obvious discontinuity with the surrounding rural landscape. An excellent example that contributes to the understanding of the tourism enclave phenomenon is Xuan Ping Li, a tourism resort of Chang’an culture (Figure 12). It is located at the Xuanping Gate in Lougetai village. The name Xuan Ping Li comes from the Xuanping Gate (the northernmost gate of the East Wall of the Chang’an CHS), which is one of the most important gates from the Han Dynasty and has the meaning of “declare peace”. The dwellings of the Han Dynasty were made of “Li”, a residential unit, such as Shangguan Li (the name of a residence unit in the Chang’an CHS in the Han Dynasty), Xuanming Li (the name of a residence unit in the Chang’an CHS in the Han Dynasty), and Changyin Li (the name of a residence unit in the Chang’an CHS in the Han Dynasty). These dwellings were mostly distributed in the north of the Chang’an CHS in ancient times and close to the Xuanping Gate. Thus, the construction of Xuan Ping Li is a new phenomenon inspired by the “Li” culture, and it was designed to restore the features of Chang’an culture to cater to tourists seeking cultural experiences.

Figure 12.

(a) The tourism resort of Xuan Ping Li after demolition (source: Xuanping Cultural Development Ltd.); (b) the trendy shops in cultural street (shown as Wenhua Chuangye Jie in the figure) in Lougetai village (source: the authors).

Furthermore, Lougetai village witnessed an increasing number of ‘cool’ tourist-focused shops, cafés, and boutiques, and tourism attractions concentrated along the main streets. Then, there was reportedly a gradual diffusion of shops, especially new culture-led commercial shops, into adjacent lanes in order to attract younger generations. Although the commercial types did not differ too much between main streets and adjacent lanes, these trendy shops were close to the tourism attractions or locations with favorable accessibility. It was apparent that the local people with rural dwellings in superior geographical locations were willing to rent out their rural dwellings or renovate shops with high added value for more profit. As one of the shop owners stated, “Heritage-led tourism helped generate income”. During this investigation, the frequent turnover of businesses as a result of the sharp increase in rents in recent years has been driven by the demand for these tourist-focused shops.

However, although the tourism enclaves and some shops, such as coffee shops and tailor-made boutiques, penetrated the Lougetai village, the nature of these businesses meant that they were focused on tourists as opposed to local residents as their customers. Indeed, one of the locals who was interviewed suggested that these places were “no ordinary people’s place” and that “it’s not the places where we can play chess or Mah-jong… it is a tourist-centered place”. As a result of these changes, the places in which the local people used to chat with their friends and neighbors were no longer familiar to them due to the influx of tourists, particularly during holiday periods when a high influx of customers came to the village. In the busy tourism seasons, some local people even closed their doors because they did not want to hear the noises of the visitors.

Production Space

As tourism projects have brought more opportunities for gaining income, many poor local people have changed their farmland to popular ‘Internet check-in sites’, which has provided them with alternative income to improve their quality of life. Indeed, muhlenbergia capillary, pennisetum alopecuroides, kochia scoparia, lavender, and sunflowers are common choices of plants to attract visitors because of their bright colors, which make for great photo opportunities to then post on social media sites (Figure 13). For local people, engaging with an ‘Internet check-in site’ is an easy way to generate profit and it also allows for more flexibility than farming. According to an interview with Mr. Zhao, who is in charge of operating an Internet check-in site, “People don’t farm. Farming is a work depending mostly upon the mercy of destiny. It’s exhausting and less well paid. Nobody wants to do it. The internet famous sites can give us more profits and I don’t need to invest more effort”.

Figure 13.

One of the Internet check-in sites with rape flowers. Note: this used to be abandoned farmland (source: one of the village leaders).

Internet check-in sites are a kind of special tourist attraction that stimulate tourists’ imaginations. As the objects found at these sites are admired and captured by the cameras of tourists, the original production farmland has shifted from having a livelihood function to a commercial function. In a picture-reading era, the operational core and development path of the Internet check-in economy is based on visual communication on social media platforms. If the internet check-in site can impress tourists and is worth sharing, then a large number of shared posts and followers stimulates more tourists to visit and engage in sightseeing, and this, in turn, generates more profits.

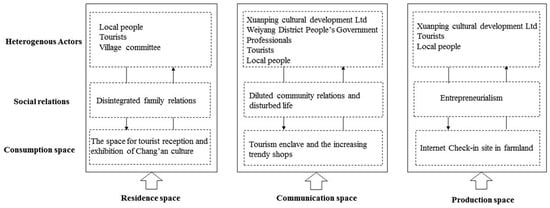

4.3.2. Social Relationship Changes

Under the influence of tourism, whilst commercial functions have been added to the original residential, communication, and production spaces, the social relationships embodied by the physical space have changed, as well (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Residential, communication, and production spaces undergo the addition of commercial space (source: the authors).

Firstly, the social relationships in the residential space have been affected by the addition of more business functions. As mentioned in the last section, in order to attract more customers, local people have turned their dwellings into showrooms for cultural products or restaurants to cater to tourists. Also, stimulated by the increase in business opportunities, some local people choose to rent out their spare rooms because the rents have increased significantly in recent years. This has enabled families to save money in order to allow their children to buy a commercial apartment in the city where there are better educational resources and medical facilities, whilst leaving their parents at home to take care of business. As a result, young generations spend more time in the city and come back to village during holidays, so Lougetai village is usually sparsely populated with only elderly people at home on weekdays. In addition, a clear division of labor has occurred, whereby males are responsible for discussing business outside villages, and females bear the cleaning, accounting, and cooking duties within rural dwellings. Couple relationships have also been diluted by increasingly rising business relationships, costs, profits, and expenditure associated with daily communication.

Secondly, regarding social relationships in the communication space, some local people have expressed negative views towards tourism. Indeed, many are not satisfied with the current communication relationships because of the compression of communication space and disturbances to their lives. The compression of communication space and disturbances to their lives are attributed to the emerging tourism businesses, which have squeezed out the places familiar to local people, such as grocery shops and breakfast stalls, in Lougetai village. Furthermore, during the peak tourism season, there are restrictions on access to the riversides or squares. Thus, the social relationships embodied in the communication space are no longer intimately maintained due to lower communication frequency.

Thirdly, regarding social relationships in the production space, traditional kinship-style mutualism has quickly changed and has been replaced by the ties of the modern economy, as the place has become deeply influenced by the tourism sector. As a result, the moral fiber of traditional rural communities has gradually given way to relationships based on interests because this new business model has generated entrepreneurialism (people running businesses themselves). Past mutualism, in terms of depending on the degree of intimacy amongst people, has been undermined by modern production relationships, because people have become more dependent on rational business laws instead of personal connections once they have engaged with tourism. Once they become shop owners, the rural conventions that used to foster moral relationships are reconfigured and adapt to rational monetary exchange.

5. Discussion

In the case study of heritage-led tourism villages around the Chang’an CHS, after space transformation, the villages have become sought-after tourism destinations. It is believed that the significance of cultural heritage in promoting place identities in connection to tourism lies in its production of a selectively reconstructed and commercialized village image. In this process, stakeholders, including the local government, capital, professionals, tourists, and local people, have engaged in “villages as arenas to play” [45]. According to the results of this study, the research questions are validated as follows.

Firstly, for heritage-led tourism villages, space transformation has caused a shift to a welcoming tourism destination. The residential space has changed from rural dwellings with a single-living function to establishments with a customer-centered business function. The traditional communication space has been compressed by tourism enclaves and tourism routes. The production space has partly changed to commercial shops and internet-famous check-in sites. Accordingly, the residential space has experienced disintegrated family relationships, whilst intimate interactions between family members have been shaken by the highlighted business functions. Original communication has been diluted with the emergence of new relationships related to business. Production has been detached from cultivated land and has embraced entrepreneurialism.

Secondly, in the process of transformation to a heritage-led tourism village, human actors, including the local government, village committee, professionals, and local people, and non-human actors, such as cultural heritage, policies and funding, and tourism infrastructure, have been integrated into the actor network through the OPP. Indeed, they have been integrated to realize tourism projects and to alleviate the tensions between cultural heritage conservation and village development.

Thirdly, the process of transformation to a heritage-led tourism village, investigated by integrating a multi-scale analysis and attention to power dynamics, has revealed how the local government, village committee, and capital driving forces participated in the space transformation. The local government assumed the responsibility of promoting local economic growth and instigated enrollment in the translation process to other diverse actors from top to bottom. Through the translation of the administrative mechanism, some actors mobilized and joined the actor network. In terms of capital, Xuanping Cultural Development Ltd. was incorporated into the fulfilment of tourism projects. The inherent proliferation requirement underpinned the maximizing of profits in the process of tourism projects. In addition, professionals, including architects and planners, were able to join in directly by providing technical guidance. The roles of tourists and local people in Lougetai village also changed as they became actors whose interests were closely related to and achieved through tourism activities.

Fourthly, the space transformation of the village involved interessement, enrollment, and mobilization processes. No matter the local government, investors, professionals, tourists, or the local people, their strategies and immediate interests were closely related to the space’s transformation to a tourism destination. These actors constantly adjusted their relationships and co-operated with each other to realize the village’s development. In the process of heritage-led tourism, sustainability lies in the balance amongst the local government, investors, professionals, tourists, and the local people.

Additionally, it was found that currently, apart from the plans and strategies adopted by the local government, capital, and professionals, who can control the space to a large extent, the influences of local people are not neglected. As the subjects who have day-to-day contact with the villages, local people are crucial to achieving sustainable multifaced dimensions involving cultural inherence, social awareness, and a tourism economy via their adaptive livelihoods, such as running hotels and restaurants. Meanwhile, some local people have resisted the tourism interruption and maintained their original lives. In doing do, they have consciously preserved the domestic landscape in contrast to the tourist-led over-commercialization. Thus, gathering local people’s insights is an important step towards ensuring ongoing sustainable development.

6. Conclusions

Understanding the space transformation of the villages around a CHS and the inter-woven actors’ negotiation processes offers a valuable perspective to seeking a new path of sustainable development that can balance diverse interests and aspirations. Lougetai in the Chang’an CHS is a favored tourism destination by virtue of its distinct cultural heritage resources. In this research, Actor Network Theory was adopted to analyze its space transformation. In this process, human factors such as the local government, village committee, investors, tourists, and local people, together with non-human factors such as administrative policies and funding, cultural heritage, land, and housing, were integrated into the actor network through OPP. Following ANT, it is of great importance to explore the impact of heritage-led tourism and how the actors are interwoven and impact the spatial changes, so as to provide an invaluable reference for sustainable development in other villages.

In the case study of heritage-led tourism villages around the Chang’an CHS, it is believed that the significance of cultural heritage in promoting place identities in connection with tourism lies in the production of a selectively reconstructed and commercialized village image. Through fine-grained analysis, the objective of this study has been met and its research questions resolved to form a loop. From the perspective of ANT, the villages around a CHS are not only mere physical spaces, but rather, dynamic social spaces involving diverse actors such as the local government, village committees, investors, professionals, tourists, and local people. In the context of ANT, the space transformation of Lougetai village was the result of interactions among heterogeneous actors. In the process of transformation to a heritage-led tourism destination, the Weiyang District government played a core role and enabled other actors, such as Xuanping Cultural Development Ltd., to invest in tourism, and enabled the village committee to help provide some assistance to community residents to operate their businesses. In addition, professionals, such as architects and planners, were able to join in directly by providing technical guidance. The role of tourists and local people in Lougetai village also changed with them becoming actors, as their interests were closely related to and could be achieved through tourism activities. For Lougetai village, its function goes beyond the purely physical space, and it is not only a place for local people’s residence, communication, and production. It is now also a place for consumers, with the actor network involving the local government, village committee, capital, professionals, tourists, and local people.

Finally, a number of recommendations can be formulated. Firstly, through teasing out the space transformation of villages around the Chang’an CHS, the interaction among the various stakeholders shows that the local government and capital have more power in China in forming growth alliances. Since the villages around the Chang’an CHS can be seen as contested spaces, more must be done to engage the local people in designing, analyzing, negotiating, and evaluating proposals, in order to settle any potential disputes and to prevent inappropriate development. Secondly, the role of commercialization can be a double-edged sword, since it can promote the local economy but also dissipate other social and cultural factors. A stable rural space system that balances economic, social, and cultural aspects is needed in order to deal with a series of crises brought about by the space transformation if sustainable development in the villages is to be realized.

Inevitably, a few limitations exist in this research. Firstly, this study investigated Lougetai village and the Chang’an CHS, and despite its representativeness, the sample size was limited. In order to improve the reliability of the study, more CHSs and concomitant villages should be selected as samples in later research to verify the universal application of the recommendations from this study. Secondly, this paper focused on actors including the local government, investors, professionals, tourists, village committees, and local people; however, other related actors are more complex and rarely mentioned, such as the government’s branch departments, including cultural heritage bureaus, and planning and landscape management bureaus. These other stakeholders might influence the space transformation and play a role in this transformation process. Thus, it is necessary to further fill these gaps in order to inform and, in turn, realize the sustainable development of the villages around a CHS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.; methodology, J.J.; validation, J.J.; formal analysis, J.J.; investigation, J.J.; resources, J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.; writing—review and editing, T.H.; supervision, T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Nottingham for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available in a publicly accessible repository that does not issue DOIs. Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, W.L.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Zhao, R. PRED Model for Conservation of cultural Heritage Sites—Case study of Chang’an cultural heritage site of Han Dynasty. J. Northwest Univ. 2006, 30, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.L. Reviews on livelihood issues of the conservation of cultural heritage sites. City Probl. 2014, 20, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.L.; Ji, J.X.; Song, M.L. A study on the governance mode of large heritage sites from a multi-scale perspective: An empirical analysis based on the Chang’an city site of the Han dynasty. Plan. Stud. 2021, 45, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, A. Urban Development in the Margins of a World Heritage Site; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pendlebury, J. Conservation and Regeneration: Complementary or Conflicting Processes? The Case of Grainger Town, Newcastle upon Tyne. Plan. Pract. Res. 2002, 17, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, J.; Short, M.; While, A. Urban World Heritage Sites and the problem of authenticity. Cities 2009, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oup Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. A History of Architectural Conservation, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. 1972. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- UNESCO. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas. 1976. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/recommendation-concerning-safeguarding-and-contemporary-role-historic-areas (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Fitri, I.; Ahmad, Y.; Ahmad, F. Conservation of Tangible Cultural Heritage in Indonesia: A Review Current National Criteria for Assessing Heritage Value. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 184, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS Burra Charter. 1979. Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/publications/burra-charter-practice-notes (accessed on 15 April 2020).