Abstract

Sustainable food consumption is seen by many as a significant challenge. Green marketers are trying to combine newer formats of marketing communications, such as influencer marketing, to change consumer’s behaviour to a more environmentally sustainable food choice. Especially, adolescents and young adults have been found to be relevant target groups. In this study, based on persuasion knowledge and reactance theory, we examined the moderating role of disclosures on the effectiveness of food influencer posts, both for sustainable and non-sustainable products. In an online 2 (non-sustainable vs. sustainable food) × 2 (no disclosure vs. disclosure) experiment (N = 332) this study finds that, surprisingly, sustainable food posts are more often recognized as advertising compared to non-sustainable food posts. Nevertheless, a disclosure increases the likelihood that a non-sustainable food post would be recognized as advertising compared to no disclosure. Finally, the recognition of selling intent decreases source credibility and ultimately decreases attitude towards the post and product, as well as liking intention.

1. Introduction

Scholars agree that moving consumers to sustainable consumption, especially food consumption, is a major and important challenge []; ensuring sustainable consumption is the 12th Sustainable Development Goal of the United Nations []. Environmentally Sustainable Food Consumption (ESFC) refers to the consumption of food products “that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimising the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generations” []. Even though food choices are hard to change since they are central to people’s lifestyles [], they are also subject to the marketing efforts of food companies []. Making food choices is a complex task that makes consumers “susceptible to a wide range of social, cognitive, affective and environmental forces” [].

Moreover, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognises children and young people as important agents of change []. Young people, as drivers of social change, are crucial for creating a more sustainable world. At the same time, previous research has indicated young people as potentially vulnerable targets of marketing communication. Young people have difficulties in understanding the selling intent of marketing campaigns, and these campaigns, especially online, are harder for teenagers to recognise compared to adults since their cognitive skills are less developed []. Young people are still developing the skills to identify commercial messages and need help in recognising their commercial and persuasive intent. This is especially true for newer forms of marketing communication [,,].

Influencer marketing is one such new form of marketing communication which has grown from representing a market size of 4.6 billion dollars to 16.5 billion dollars during the last five years, and it is expected to grow even more []. Social media influencers are “people who have built a sizeable social network of people following them” [] (p. 798). Through social media, these influencers can disseminate information to a multitude of people via interpersonal online interactions [,,]. Brands increasingly create alliances with social media influencers to promote their products []. Endorsements from social media influencers are considered to be evaluated like word-of-mouth endorsements since they are interwoven with influencers’ daily non-branded content []. “Influencers function as brand ambassadors by creating sponsored content (e.g., pictures of [themselves with] the brand or product), mentioning the product or the brand in picture captions or tags, or by sharing or being part of larger advertising campaigns and events” [] (p. 199). The Belgian SMI Barometer 2023 [] shows that 28.3% of respondents (between 16 and 39) that follow influencers, content creators or celebrities bought something the influencer advertised in the last three months. Moreover, 33.2% of respondents started following the advertised brand and 45.1% looked for more information about the advertised brand. In sum, using influencers seems to be an effective marketing strategy. Based on social cognitive theory [], it can be expected that influencers function as symbolic models based on which users model their own behaviour.

Since brand endorsements from social media influencers highly resemble non-commercial content, people, especially younger audiences, do not seem to recognise it as commercial [,]. Using the Persuasion Knowledge Model [], we consider it essential to study how we can reinforce the use of persuasion knowledge in influencer marketing. Regulatory parties have recommended the use of disclosures. In 2017, Instagram introduced a standardised built-in disclosure which takes the form ‘Paid partnership with [brand]’ []. Prior research has shown that sponsorship disclosures can increase ad recognition [,]. However, the FTC suggests that the standardised disclosure used by Instagram might not attract attention []. Therefore, it is crucial to study the effect of a different disclosure. Moreover, given the topic of environmentally sustainable food posts discussed in their posts, it might be even more critical to disclose a persuasive intent of such a post because it might be harder to distinguish for (young) consumers since the commercial intent might not be evident based on the type of product presented.

In sum, the current study aims to offer three contributions. First, the role of influencer marketing for sustainable food on young consumers’ responses (adolescents and young adults) is compared to non-sustainable food. More specifically, how a post by an influencer is processed is examined through the moderating role of sponsorship disclosure. Previous research has indicated that disclosure can help consumers identify the persuasive intent of an influencer post []. Nevertheless, this study aims to replicate this finding in the context of (non-)sustainable food. Second, this study aims to study the underlying processing mechanisms of influencer posts promoting sustainable food through the mediating roles of recognition of selling intent and source credibility. Finally, the current study also aims to contribute to the debate about the effects of influencer marketing on adolescents and young adults by examining three different digital marketing outcomes, namely attitude toward the posts, attitude toward the product and liking intention. It provides insights into the effects of influencer marketing for sustainable (food) products which are helpful for advertisers, educators, and public policy makers.

2. Literature

2.1. Promoting Sustainable Food on Instagram

Research has shown that both word-of-mouth on social media (sWOM) and influencer marketing have become influential in shaping people’s, including young people, attitudes and behaviours [,,]. There is limited evidence in the context of environmental sustainable food choice. Nevertheless, in terms of (un)healthy food choices, previous research has indicated that children’s unhealthy snack intake increases after exposure to influencer marketing []. Recently, De Jans et al. [] showed that influencers’ healthy and athletic lifestyles could positively affect children’s healthy snack choices. There has also been research conducted on general pro-environmental behaviour. For example, Dekoninck and Smuck [] show that following influencers that address cause-related topics, such as environmental issues, are associated with higher pro-environmental behaviour intentions. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how food choices, and specifically, pro-environmental food choices are influenced by influencer marketing and how these messages are processed.

The social cognitive theory [] offers an interesting theoretical starting point for understanding the effect of influencers on people’s attitudes and behaviour. According to social cognitive theory, human behaviour results from personal, environmental and behavioural factors. According to the social cognitive theory, media in general, thus also social media and influencers on these platforms, can affect an individual’s behaviour directly or through social mediation. People are informed, motivated and guided through the direct pathway, whereas through the socially mediated pathway, people adopt, support, spread and share innovative ideas or behaviours.

Like all behaviours, socially mediated behaviour occurs within a specific setting, e.g., social media, and is affected by cognitive, environmental and behavioural factors. For example, it can be expected that when exposed to an influencer who posts about environmental issues, the social media user models the suggested behaviour. This way, the behaviour is learned from observing the influencer’s behaviour and behavioural norms. At the same time, the users’ environment is considered to ensure that the suggested behaviour can be achieved. For example, a social media user who needs more resources to buy environmentally sustainable food will unlikely adopt the behaviour (i.e., perceived self-efficacy) []. In sum, through observational learning, receivers of influencers’ posts see and learn about new products. By showing sustainable food, influencers can act as symbolic models: people observe the influencer and will try to reproduce that behaviour [].

2.2. Recognition of Selling Intent on Instagram

Moreover, the resemblance of the post to non-commercial posts causes people not to recognise it as commercial [,]. The Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM) [] provides a conceptual basis to understand how consumers respond to persuasive messages in general, and can also be applied in the context of influencer marketing [,]. Based on PKM, consumers are assumed to use their persuasion knowledge to process and evaluate persuasive messages. This persuasion knowledge comprises two components []: conceptual and attitudinal persuasion knowledge. Conceptual is typically considered as the recognition of a persuasive message as advertising or recognising the selling intent of a persuasive message (tactic knowledge). The attitudinal dimension refers to the attitudes that develop when processing a persuasive message. It is typically assumed that more critical processing takes place []. Research based on PKM indicates that young consumers need to understand the commercial and persuasive intentions and techniques used in advertising formats to identify and distinguish advertising from editorial or entertainment formats [,].

Persuasion knowledge is developed, among others, by exposure to persuasive messages []; since young consumers are less often exposed to sustainable food marketing and because the commercial and non-commercial content might be even more intertwined than in a typical influencer post, it can be expected that it will be harder to recognise this type of marketing compared to unsustainable food marketing. Therefore, we expect the following:

H1.

An Instagram post promoting sustainable food will lead to lower recognition of selling intent than an Instagram post promoting non-sustainable food.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Sponsorship Disclosures

As mentioned before, new advertising formats, such as influencer marketing, intertwine non-commercial and commercial content, making it harder to recognise its persuasive intent []. Influencers particularly mix their sponsored posts with unsponsored posts and as a result, these sponsored posts are not necessarily perceived as advertising. One way to increase young consumers’ likelihood of recognising selling intent is to add a sponsorship disclosure to the influencer’s message.

Disclosures aim to help consumers identify this persuasive intent and thus to activate persuasion knowledge. Previous research has extensively shown that disclosures are helpful cues to increase persuasion knowledge (e.g., in television programs [], movies [] or online news []). In the context of influencer marketing, Boerman et al. [] found that the use of a disclosure increases the recognition of a persuasive intent in influencer marketing. In sum, a disclosure can help young consumers to differentiate advertising from other content by activating conceptual persuasion knowledge []. Therefore, we expect:

H2.

A disclosure in an Instagram post will result in higher recognition of selling intent than without such a disclosure.

Since persuasion knowledge is gained through experience, it might be expected that it is generally easier for a user to recognise the selling intent of a post promoting a non-sustainable food product when a disclosure is present since they might be more familiar with these types of messages or even with these brands. A disclosure, then, might reinforce this recognition. At the same time, in a non-sustainable food post, the commercial intent might already be more apparent. For example, users are more used to seeing this type of product or because it is not hidden within a social cause.

On the other hand, in an Instagram post promoting sustainable food behaviour, clarification might be needed for a user about whether this message is trying to sell them something or whether it is just raising awareness about environmental concerns. In that case, a disclosure might help them recognise the commercial nature, and therefore might increase the recognition of selling intent. At the same time, given the newer format and a lower familiarity with this type of product, more than a disclosure might be required to convince a user that the post is trying to sell them something. Since previous research does not provide a clear direction, a non-directional hypothesis was formulated:

H3.

A disclosure in an Instagram post moderates the effect of an Instagram post promoting food on recognition of selling intent.

2.4. The Role of Source Credibility and Consumer Responses

Following conceptual persuasion knowledge (i.e., recognition of selling intent), consumers cope with a persuasive attempt []. This coping attempt is neutral: “we do not assume that people invariably or even typically use their persuasion knowledge to resist a persuasion attempt. Rather, their overriding goal is simply to maintain control over the outcome(s) and thereby achieve whatever mix of goals is salient to them” [] (p. 3). Indeed, we can expect that when the recognition of selling intent is activated, young consumers will try to cope with the advertisers’ intentions [,]. This mechanism can be applied to specific commercial messages [] and is part of the coping mechanism that young consumers will activate when exposed to a persuasive message. One coping mechanism that can be activated is scrutinising the message’s content and evaluating the influencer’s credibility, and thus the influencers’ motives [].

In line with the reactance theory [], it can be expected that consumers respond negatively towards this persuasive attempt because of this recognition and this coping attempt since they do not want to be manipulated. As such, when they recognise a persuasive intent, they might respond in the opposite direction of what is intended by the persuasive message [,]. Hence, when young consumers perceive a strong manipulative intent, such as recognising an influencer post as advertising, they might develop negative perceptions of the message’s source [,]. They might decrease their source credibility, defined as []’ a message sender’s positive characteristics that influence receivers’ acceptance of the message communicated’ [] (p. 4406). Therefore, we expect the following:

H4.

Recognition of selling intent will decrease the source credibility of the influencer.

When a source is perceived as credible and does not appear to have any self-interest in recommending a product, consumers will pay more attention to the message, and it will be more persuasive [,,]. Previous research has shown that higher source credibility increases attitude towards the product []. Conversely, when consumers perceive a source as having low credibility, they will discount the claims made in the persuasive message []. As a result, the consumers’ attitude towards the product will decrease. Therefore, we expect the following:

H5.

Source credibility, in turn, will increase (a) attitude toward the ad, (b) attitude toward the product and (c) liking intention.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

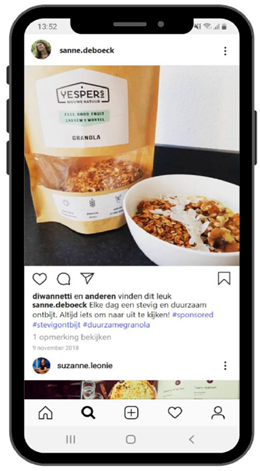

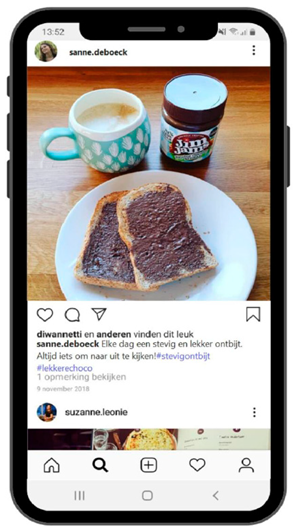

An online experiment with a 2 (sustainable vs. non-sustainable product) × 2 (sponsorship disclosure: present or absent) design was set up to test the hypotheses. Respondents were randomly shown a mock Instagram feed (see Appendix A and Appendix B for two examples) containing the manipulated post. Since Instagram is a primarily mobile social medium, the feed only contained the manipulated post and the top of a second fictitious post. Existing brands were used to make the stimulus material as realistic as possible. However, they are not known in Belgium, which reduces the risk of brand familiarity effects. In all conditions, the participants were presented with pictures of the products, not the source, to avoid potential confounds. Moreover, all posts were from the fictitious “Sanne De Boeck”, a common name in Belgium (Flanders).

The post for a sustainable product read as follows (translated from Dutch): “Every day a hearty and sustainable breakfast. Always something to look forward to! #heartybreakfast #sustainablegranola”. The post for a non-sustainable product read: “Every day a hearty and yummy breakfast. Always something to look forward to! #heartybreakfast #yummychocopaste”.

Based on Evans et al. [], the presence of a sponsorship disclosure was manipulated by using #sponsored. Moreover, the disclosure was presented as the first hashtag in the caption.

Respondents were contacted by asking Belgian youth- and sports clubs to distribute our survey link to their members in April 2020, which allowed us to reach both young adults and adolescents simultaneously. In total, 427 participants took part in the survey. Thirteen people did not have an Instagram account and were automatically re-directed to the end of the survey and thirty more stopped the survey themselves. From the remaining 384 participants who continued the survey, 50 did not complete the survey. Participants who met the inclusion criteria and finished the survey (N = 332) were in the age range from 12 to 25 (M = 18.72, SD = 3.62), and the majority (72.0%) was female. Most respondents used Instagram multiple times daily (83.4%) and reported following influencers on the platform (80.1%).

A randomization check displayed no significant differences with respect to age F (1, 328) = 0.294, p = 0.588, gender χ2 (3) = 1.56, p = 0.668 or Instagram use χ2 (3) = 9.06, p = 0.170 between the four experimental groups. Table 1 provides an overview of the sample descriptives per experimental group.

Table 1.

Summary of descriptives per experimental group.

3.2. Procedure

When opening the survey link, respondents were, after a brief introduction, asked to indicate whether they were older than 18 or not. When they were, they were presented with an informed consent form that they needed to sign. When they were not, we asked for parental consent. Next, respondents were asked whether they owned an Instagram account to filter out those that did not. The actual survey started with questions regarding age and gender, frequency of Instagram use, and whether the respondent followed influencers or not. After these introductory questions, respondents were exposed to one of the experimental Instagram feeds. They were asked to rate their like intention, attitude towards the Instagram post, attitude towards the product, recognition of selling intent, perceived sustainability of the product and source credibility. Finally, a manipulation check tested whether they had seen the disclosure, if any, in the post they were exposed to, and respondents were thanked for their participation.

3.3. Measures

Like intention. Like intention was measured with a single item, “To what extent do you agree with the following statements: (1) I would like this post” on a scale from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree (M = 2.15, SD = 1.03).

Attitude towards the Instagram Post. Attitude towards the Instagram Post was measured with six items, “Evaluate the post you just watched: (1) unpleasant/pleasant, (2) not fun/fun, (3) boring/interesting, (4) tasteless/tasteful, (5) not creative/creative, (6) bad/good” on a bipolar semantic differential from 1 to 5 (M = 2.47, SD = 0.77, α = 0.88) based on Hill et al. [] and Biehal et al. [].

Attitude towards the product. Attitude toward the product was measured with five items, “Evaluate the product you saw in the post by Sanne De Boeck: (1) not attractive/attractive, (2) bad/good, (3) unpleasant/pleasant, (4) unfavourable/favourable, (5) unlikeable/likeable” on a bipolar semantic differential from 1 to 5 (M = 2.95, SD = 0.76, α = 0.87) based on Spears and Singh [] and Jansen et al. [].

Recognition of selling intent. Recognition of selling intent was measured with three items, “To what extent do you agree with the following statements: (1) This Instagram post is advertising, (2) This Instagram post is commercial, (3) This Instagram post contains advertising” on a scale from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree (M = 4.02, SD = 0.83, α = 0.84) based on Van Reijmersdal et al. [].

Perceived sustainability of the product. Perceived sustainability of the product was measured with six items, “Evaluate the product you saw in the post by Sanne De Boeck: (1) unhealthy/healthy, (2) cheap/expensive, (3) globally available/locally available, (4) artificial/natural, (5) unbalanced food intake/balanced food intake, (6) rich in fat/sugar/low in fat/sugar” on a bipolar semantic differential from 1 to 5 (M = 2.87, SD = 0.89, α = 0.86) based on Żakowska-Biemans et al. [].

Perceived source credibility. Perceived source credibility was measured with five items, “Evaluate Sanne De Boeck, the person who posted the picture: (1) unreliable/reliable, (2) not honest/honest, (3) untrustworthy/trustworthy, (4) not sincere/sincere, (5) not credible/credible” on a scale from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree (M = 3.00, SD = 0.73, α = 0.91) based on Ohanian [].

Manipulation check of the disclosure. Based on De Veirman et al. [], respondents were asked whether they had seen any of the following disclosures: #sponsored, #spon, #advertisement, #ad, #notsponsored, and #nonspon. They could also indicate that they had not seen any of these disclosures. These responses were then recoded into correct and incorrect recognition of the disclosure (depending on the allocated condition of the respondent).

3.4. Manipulation Check

A first manipulation check tested whether the respondents perceived the product as sustainable. An independent samples t-test indicated that the respondents in the sustainable food condition (M = 3.56, SD = 0.48) perceived the product as more sustainable than the respondents in the non-sustainable food condition (M = 2.15, SD = 59, t (311.94) = −23.81, p < 0.001).

A second manipulation check tested whether the respondents in the disclosure condition recognised the disclosure when asked. A total of 66.1% of the respondents in the disclosure condition correctly identified the disclosure they were exposed to, and 20.2% of those in the disclosure condition incorrectly indicated they had not seen a disclosure. Finally, 82.2% of the respondents in the non-disclosure condition correctly indicated that they had not seen a disclosure. Sixty-two respondents who did not correctly identify the presence or absence of a disclosure were removed from further analyses. The excluded versus included groups did not differ in gender χ2 (1) = 0.206, p = 0.650 or Instagram use χ2 (2) = 1.373, p = 0.503, but they did differ in age t (323) = −3.66, p < 0.001. More specifically, the excluded group was on average younger (M = 17.29, SD = 3.55) compared to the included group (M = 19.12, SD = 3.53).

4. Results

To test hypothesis 1, a univariate general linear model was performed for recognition of selling intent as dependent variables, and with food condition (0 = non-sustainable food, 1 = sustainable food) and disclosure presence (0 = not present, 1 = present) as independent variables. Due to the large proportion of women in the sample and the large range in age, both age and gender were entered as control variables.

A significant main effect of the food condition was found. However, the effect was in the opposite direction of what was expected: an Instagram post promoting sustainable food (M = 4.20, SD = 0.73) resulted in significantly more recognition of selling intent than an Instagram post promoting non-sustainable food (M = 3.95, SD = 0.88), F(1, 257) = 6.14, p = 0.014. Since the effect is opposite to what was expected, H1 is rejected.

Further, a significant main effect of the disclosure was found: an Instagram post including a sponsorship disclosure (M = 4.26, SD = 0.65) resulted in significantly more recognition of selling intent than an Instagram post without such a disclosure (M = 3.87, SD = 0.92), F(1, 257) = 16.08, p < 0.001. Hence, H2 is accepted.

Finally, the interaction effect between food condition and disclosure was found to be marginally significant, F(1, 257) = 3.35, p = 0.068. Looking first at the comparisons within the food conditions, the post hoc t-test revealed that in the non-sustainable food conditions, participants recognised the selling intent better when there was a disclosure present (M = 4.23, SD = 70) than when there was no disclosure present (M = 3.66, SD = 0.96), t (120.67) = −3.922, p < 0.001). However, in the sustainable food condition, a disclosure (M = 4.30, SD = 0.60) did not improve the recognition of selling intent, t (126) = −1.65, p = 101, compared to when the disclosure was absent (M = 4.09, SD = −0.94).

Further, when only examining the disclosure condition, there was a significant difference between the non-sustainable food condition (M = 3.66, SD = 0.96) and the sustainable condition (M = 4.09, SD = 0.94) in recognition of the selling intent, t (127) = −2.67, p = 0.009. When there is a disclosure present, there is no difference between the food conditions, t (132) = −0.60, p = 0.551. In sum, a disclosure in an Instagram post for non-sustainable food does increase the recognition of selling intent. However, this is not the case for sustainable food. Therefore, H3 is partially accepted.

To test hypotheses 4 and 5, three mediation models (one for each DV) were tested using PROCESS_v4.1 (model 4) with recognition of selling intent as the independent variable, source credibility as the mediator and (a) attitude toward the ad, (b) attitude toward the product and (c) liking intention as dependent variables. Similar to the univariate general linear model, age and gender were entered as control variables. Table 2 provides an overview of the standardised regression coefficients.

Table 2.

Standardised regression coefficients.

First, recognition of selling intent has a significant negative effect on source credibility (β = −0.28, p < 0.001). Both age and gender have a non-significant impact. Thus, H4 is accepted: recognition of selling intent decreases source credibility. Next, source credibility has a significant, positive impact on attitude toward the ad (β = 0.29, p < 0.001), attitude toward the product (β = 0.34, p < 0.001), and liking intention (β = 0.26, p < 0.001). Age has a significant effect on attitude toward the product (β = 0.12, p = 0.039) and on liking intention (β = −0.24, p < 0.001) but not on attitude toward the ad (β = 0.02, p = 0.804). Gender has a significant effect on attitude toward the ad (β = 0.13, p = 0.043), liking intention (β = 0.13, p = 0.031) and a marginally significant effect on attitude toward the product (β = 0.12, p = 0.066). Hence, H5 is accepted: source credibility increases (a) attitude toward the ad, (b) attitude toward the product and (c) liking intention.

5. Discussion

This study explored whether using a disclosure in an Instagram post that promoted sustainable food would affect the recognition of its selling intent compared to an Instagram post that promoted non-sustainable food. In addition, we examined whether a disclosure would moderate this recognition and whether this would result in lower levels of source credibility and ultimately affect consumer responses. Contrary to our expectations, an influencer post about a sustainable food product resulted in higher recognition of selling intent. Based on the Persuasion Knowledge Model [], we expected that recognising the commercial intent of a sustainable food product would have been more difficult because the message would be more intertwined with non-commercial motives. Since consumers could be expected to be more frequently exposed to messages about non-sustainable food products (due to their high availability), we expected a higher likelihood that these would be recognised as advertising. However, our results indicated the opposite (although the presentation of the two products was held similar). Given that we are the first to examine the effect of recognition of selling intent on non-sustainability versus sustainability, this finding requires further research, which can distinguish between, e.g., the products’ nature or familiarity.

In line with previous research [], we found that a disclosure increases the likelihood that an influencer post is recognised as advertising compared to when no disclosure was present. This seems to indicate that the presence of a disclosure can indeed activate conceptual persuasion knowledge []. This is in line with research in the context of television programs [], movies [] or online news []). Furthermore, Boerman et al. [] found that the use of a disclosure increases the recognition of a persuasive intent in influencer marketing. As such, our findings confirm that a disclosure can help young consumers to differentiate advertising from other content by activating conceptual persuasion knowledge [].

Moreover, our findings also provide initial evidence that there might be a difference in recognition based on the nature of the product that is being advertised. More specifically, our findings indicate that for an Instagram post with a non-sustainable food product, a disclosure increases recognition of selling intent, whereas this does not seem to be the case for a sustainable food product. What can be observed from the results is that the recognition of selling intent for a sustainable food product is already very high; it is likely that it could not be heightened further by the addition of a disclosure. This is contrary to our expectations based on the Persuasion Knowledge Model []: persuasion knowledge is gained through experience. It can be expected the exposure to non-sustainable food, or non-sustainable products in general is higher, and therefore persuasion knowledge would be more elaborate for these kinds of products. Therefore, a disclosure would not seem necessary when advertising a non-sustainable product. However, our findings seem to contradict this expectation. The higher level of recognition of selling intent for the sustainable food product might be explained by the novelty aspect of the sustainable food product. In advertising research, novelty has been often shown to affect brand reactions []. Based on the Elaboration Likelihood Model [], Sheinin et al. [] found that novelty leads to more peripheral processing, and therefore better short-term recall. This might have reduced the need for a disclosure to recall the persuasive intent of the influencer post. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to understand this interaction effect better.

Finally, in line with previous research [], we can also confirm that when recognition of selling intent increases, the source credibility decreases, negatively affecting consumer outcomes (i.e., attitude toward the ad, toward the product and liking intention). This confirms the expectations based on the reactance theory []: consumers do not want to feel manipulated and therefore counteract the intended behaviour suggested by the influencer. Consumers tend to perceive influencers as more trustworthy and authentic content creators [] and thus credible, which makes them more likely to persuade a consumer according to the source credibility theory []. A cue—in this case, a disclosure—that persuades them otherwise will change consumers’ perceptions.

5.1. Practical Implications

Different stakeholders can use the findings from our research in their practices. First, young consumers on Instagram seem to be already able to recognise commercial messages. The high level of recognition of selling intent in both the non-sustainable and sustainable food conditions seem to indicate this. This illustrates that even young consumers have developed persuasion knowledge to employ when processing influencer marketing messages. Nevertheless, it is important to note here that respondents were prompted with the question of whether they recognised the selling intent. This type of cue is very rare in a real-life Instagram context. Therefore, it might be unlikely that the same high levels would be found in real-life. This again points out the importance of using a disclosure in Instagram posts. Our findings demonstrate indeed that using a disclosure can help young consumers recognise the selling intent of Instagram posts.

These findings are thus also important for regulators, such as the FTC, and for social media platforms, such as Instagram, since they demonstrate that a disclosure can increase ad recognition. For regulators, this is an important finding because it shows that a disclosure can be an effective strategy to help young consumers recognize a selling intent. Although our disclosure manipulation check indicated that on average the respondents that were not able to recognize the presence or absence of a disclosure correctly were on average younger than those who did. Nevertheless, this is also interesting for social media platforms since it seems to point out that consumers do recognize selling intent and that this can diminish the credibility of the influencers, resulting in a decreased marketing outcomes. Nevertheless, earlier research has found that the recognition of selling intent does not automatically deteriorate marketing outcomes. For example, De Keyzer et al. [] found that the recognition of selling intent does not automatically increase critical processing, and as such, does not decrease brand attitude. In contrast, the effect was, albeit marginally significant, positive. In line with the reactance theory [], platforms managers should realize that when consumers feel manipulated by an influencer post, consumers will respond by reacting against it.

For brands and influencers, it is important to realise that the presence of a disclosure can decrease an influencer’s credibility, which in turn leads to less positive consumer responses. Therefore, examining how to mitigate this negative effect might be crucial. Moreover, it is important to note that previous research has indicated that disclosing the persuasive intent of messages is not necessarily bad. According to De Keyzer et al. [], disclosures lead to more elaborate processing, which helps encode a brand in memory, making it easier for a consumer to retrieve it from memory later on. This idea aligns with PKM since Friestad and Wright [] emphasised that activating persuasion knowledge does not automatically lead to counter-arguing. This counter-arguing is more likely the result of reactance towards feeling manipulated. In line with previous scholars [,,], it is crucial to distinguish conceptual from attitudinal persuasion knowledge to improve our understanding of consumers’ responses to influencer marketing. Moreover, there seems to be a difference between non-sustainable and sustainable food: a disclosure affects the recognition of selling intent of non-sustainable food posts but not of sustainable food posts. Our findings seem to indicate that for sustainable food the disclosure does not increase the recognition of selling intent. The recognition was already high, potentially due to the novelty of the product, and the resulting processing of the message. As such, adding a disclosure for a sustainable food product does not have to scare sustainable food brands. On the other hand, the selling intent of non-sustainable food products that are paired with a disclosure are more likely to be recognized. In line with De Keyzer et al. [], this also should not necessarily scare non-sustainable food brands. Finally, since the recognition of selling intent decreases the source credibility of the influencer, it does seem necessary for influencers to examine means to re-establish their source credibility.

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

Our limitations provide interesting research avenues to improve our understanding of consumers’ responses to influencer marketing. In the current study, respondents were exposed to one static Instagram post from a non-familiar influencer. The choice of a non-familiar influencer resulted from our hypotheses: we preferred not to choose a well-known influencer, given that previous research has indicated that influencer characteristics could affect our findings. For example, the size of the follower base or the characteristics of the relationship between the influencer and the respondents have all been shown to affect how people respond to persuasive messages on social media. For example, Boerman and Müller [] found that influencers’ follower base also affects the activation of conceptual knowledge: a sponsored post by a macro-influencer was identified more as advertising than a nano-influencer.

Second, the current study has been conducted in such a context to ensure ecological validity: by showing realistic stimulus material and asking respondents to imagine that the message was shown in their feed. The social media context might also affect the responses to influencer marketing. First, the current study is set in an Instagram setting since this is a popular platform used by adolescents and young adults. Nevertheless, in line with Voorveld [], we believe consumer responses to persuasive messages can differ based on the social media platform in which they are shown. The platform in which persuasive messages are embedded can also be used as a source of information. Therefore, future research could test the current model in different media platforms to test the robustness of the model.

Moreover, respondents were now only exposed to one single Instagram post. Nevertheless, in a real-life setting, respondents would be exposed to multiple messages (at least before and after exposure to the post). In line with the context appreciation theory [], we suggest future research to consider the content of surrounding messages.

Fourth, the sustainable food condition presented a different product, and therefore a different picture, compared to the non-sustainable food condition. The reasoning behind this choice was to increase the likelihood that the conditions would significantly differ in terms of perceived sustainability. Although the manipulation checks indeed indicated that these two conditions significantly differed in terms of perceived sustainability, this might have also introduced a potential confound in terms of, for example, product involvement. Moreover, the pictures also have slight differences, although in both we ensured that the picture showed the actual product as well as the packaging of the product. Nevertheless, future research is encouraged to use a cleaner operationalization to disentangle the effects of product involvement and sustainability.

Next, De Keyzer et al. [] indicate that relational characteristics (i.e., perceived homophily, perceived tie strength and perceived source credibility) might affect consumer’s responses. The parasocial relationship between the influencer and the follower has been identified to play a role in consumers’ responses to influencer marketing in the sense that a strong parasocial relationship might function as a barrier for reactance [,] in which a stronger parasocial relationship between the influencer and the respondent already results in higher levels of trustworthiness and credibility []. Therefore, influencer characteristics could mitigate negative consumer responses.

Furthermore, cultural characteristics might also affect our findings. Previous research has indicated that culture can affect social media participation, as well as the engagement with branded content [,]. Moreover, Ur Rahman et al. [] propose that cultural dimensions also affect sustainable consumption. In line with much of the previous research, the current study was conducted in a Western setting and the question remains whether these findings could be extrapolated to other markets. Therefore, we suggest future research to consider taking the cultural dimensions into account as potential moderating variables.

In conclusion, our findings contribute to research on influencer marketing for food products in social media. Specifically, we examined whether influencer marketing for sustainable food products by so-called greenfluencers elicits positive responses in adolescents and young adults. The answer to this question seems nuanced. Given the age group and the call from regulators to add disclosures to sponsored content, we studied whether a disclosure would hinder positive responses. Our findings indicate that, in line with expectations based on the Persuasion Knowledge Model [], a disclosure can hinder positive responses, primarily through the recognition of selling intent and, as a result, a reduction in source credibility. Surprisingly, there is initial evidence that sustainable food products are more easily recognised as sponsored. In contrast, the disclosure seems necessary for the non-sustainable food products to be recognised as sponsored. Finally, this study contributes to our understanding of the processing of influencer marketing by replicating the connection between recognition of selling intent, source credibility and three marketing outcomes (attitude toward the post, attitude toward the product and liking intention) in the context of sustainable food products.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to regulations at the host institution: master students are not obliged to request ethical approval for data collection in the context of their thesis project.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects (or their parents in the case of minors) involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to no consent from participants to publicly share their data.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to Sofie Adriaens, Business Communication, for their help with research design and the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Instagram Post for Sustainable Food with Disclosure

Appendix B. Instagram Post for Unsustainable Food without Disclosure

References

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Spruyt, A.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Van Lippevelde, W.; De Steur, H.; Verbeke, W. Environmentally Sustainable Food Consumption: A Review and Research Agenda from a Goal-Directed Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ecolex. Ecolex. The Imperative of Sustainable Production and Consumption. In Proceedings of the Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption, Oslo, Norway, 19–20 January 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, S.; Mccarthy, M.; Collins, A.; Mcauliffe, F. Can Existing Mobile Apps Support Healthier Food Purchasing Behaviour? Content Analysis of Nutrition Content, Behaviour Change Theory and User Quality Integration. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bublitz, M.G.; Peracchio, L.A.; Block, L.G. Why did I Eat that? Perspectives on Food Decision Making and Dietary Restraint. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panic, K.; Cauberghe, V.; De Pelsmacker, P. Comparing TV Ads and Advergames Targeting Children: The Impact of Persuasion Knowledge on Behavioral Responses. J. Advert. 2013, 42, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jans, S.; Vanwesenbeeck, I.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L.; Rozendaal, E.; Van Reijmersdal, E.A. The Development and Testing of a Child-Inspired Advertising Disclosure to Alert Children to Digital and Embedded Advertising. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, L.J.; Baldwin, D.A. What can the Study of Cognitive Development Reveal about Children’s Ability to Appreciate and Cope with Advertising? J. Public Policy Mark. 2005, 24, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozendaal, E.; Buijzen, M.; Valkenburg, P. Comparing Children’s and Adults’ Cognitive Advertising Competences in the Netherlands. J. Child. Media 2010, 4, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Inc. Influencer Marketing Market Size Worldwide from 2016 to 2023; Statista Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 2023. [Google Scholar]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram Influencers: The Impact of Number of Followers and Product Divergence on Brand Attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2008, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keyzer, F. Brand Communication on Social Networking Sites. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Antwerp, Antwerpen, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic Word-of-Mouth Via Consumer-Opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C. The Effects of the Standardized Instagram Disclosure for Micro- and Meso-Influencers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 103, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Bruwiere, I.; Mollaert, E. SMI Barometer 2023 Insights into How Belgians Experience Branding through Social Media and Influencer Marketing; Arteveldehogeschool: Gent, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; p. 617. [Google Scholar]

- Boerman, S.C.; Willemsen, L.M.; Van Der Aa, E.P. This Post is Sponsored. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 38, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.J.; Phua, J.; Lim, J.; Jun, H. Disclosing Instagram Influencer Advertising: The Effects of Disclosure Language on Advertising Recognition, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intent. J. Interact. Advert. 2017, 17, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friestad, M.; Wright, P. The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instagram Inc. Why Transparency Matters: Enhancing Creator and Business Partnerships; Instagram Inc.: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Veirman, M.; Hudders, L. Disclosing Sponsored Instagram Posts: The Role of Material Connection with the Brand and Message-Sidedness when Disclosing Covert Advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 39, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Trade Commission. Native Advertising: A Guide for Businesses; Federal Trade Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- De Keyzer, F.; Dens, N.; De Pelsmacker, P. Don’T be so Emotional! How Tone of Voice and Service Type Affect the Relationship between Message Valence and Consumer Responses to WOM in Social Media. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The Impact of Brand Communication on Brand Equity through Facebook. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, A.E.; Hardman, C.A.; Halford, J.C.G.; Christiansen, P.; Boyland, E.J. Food and Beverage Cues Featured in YouTube Videos of Social Media Influencers Popular with Children: An Exploratory Study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jans, S.; Van de Sompel, D.; Hudders, L.; Cauberghe, V. Advertising Targeting Young Children: An Overview of 10 years of Research (2006–2016). Int. J. Advert. 2017, 38, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekoninck, H.; Schmuck, D. The Mobilizing Power of Influencers for Pro-Environmental Behavior Intentions and Political Participation. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.S.; Choe, M.; Zhang, J.; Noh, G. The Role of Wishful Identification, Emotional Engagement, and Parasocial Relationships in Repeated Viewing of Live-Streaming Games: A Social Cognitive Theory Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jans, S.; Spielvogel, I.; Naderer, B.; Hudders, L. Digital Food Marketing to Children: How an Influencer’s Lifestyle can Stimulate Healthy Food Choices among Children. Appetite 2021, 162, 105182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerman, S.C.; Müller, C.M. Understanding which Cues People use to Identify Influencer Marketing on Instagram: An Eye Tracking Study and Experiment. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 6–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Tan, S.; Chen, X. Investigating Consumer Engagement with Influencer- Vs. Brand-Promoted Ads: The Roles of Source and Disclosure. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daems, K.; De Keyzer, F.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Moons, I. Personalized and Cued Advertising Aimed at Children. Young Consum. 2019, 20, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pelsmacker, P.; Neijens, P.C. New Advertising Formats: How Persuasion Knowledge Affects Consumer Responses. J. Mark. Commun. 2012, 18, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Neijens, P.C. Sponsorship Disclosure: Effects of Duration on Persuasion Knowledge and Brand Responses. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 1047–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, T.; Geuens, M. PP for ‘product Placement’or ‘puzzled Public’? Int. J. Advert. 2015, 32, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazeen, M.A.; Wojdynski, B.W. The effects of disclosure format on native advertising recognition and audience perceptions of legacy and online news publisher. Journalism 2018, 21, 1965–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; Friestad, M.; Boush, D.M. The Development of Marketplace Persuasion Knowledge in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. J. Public Policy Mark. 2005, 24, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, D.; Tomczak, T.; Herrmann, A. The Moderating Effect of Manipulative Intent and Cognitive Resources on the Evaluation of Narrative Ads. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 510–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.W. A Theory of Psychological Reactance; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Sagarin, B.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Rice, W.E.; Serna, S.B. Dispelling the Illusion of Invulnerability. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Fischer, E.; Main, K.J. An Examination of the Effects of Activating Persuasion Knowledge on Consumer Response to Brands Engaging in Covert Marketing. J. Public Policy Mark. 2008, 27, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.R.; Wood, M.L.M.; Paek, H. Increased Persuasion Knowledge of Video News Releases: Audience Beliefs about News and Support for Source Disclosure. J. Mass Media Ethics 2009, 24, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, R.; Buzeta, C.; Velásquez, M. Sidedness, Commercial Intent and Expertise in Blog Advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4403–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, R.; Zhang, Y. Consumer Product Evaluation: The Interactive Effect of Message Framing, Presentation Order, and Source Credibility. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2000, 9, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M. Understanding Two-Sided Persuasion: An Empirical Assessment of Theoretical Approaches. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 24, 615–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Kang, Y.R. Factors Influencing eWOM Effects: Using Experience, Credibility, and Susceptibility. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2011, 1, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Effects of Celebrity Athlete Endorsement on Attitude Towards the Product: The Role of Credibility, Attractiveness and the Concept of Congruence. Int. J. Sport. Mark. Spons. 2007, 8, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Gotlieb, J.; Marmorstein, H. The Moderating Effects of Message Framing and Source Credibility on the Price-Perceived Risk Relationship. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Mazis, M. Measuring Emotional Responses to Advertising. Adv. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Biehal, G.; Stephens, D.; Curio, E. Attitude Toward the Ad and Brand Choice. J. Advert. 1992, 21, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, N.; Singh, S.N. Measuring Attitude Toward the Brand and Purchase Intentions. J. Curr. Issues Amp. Res. Advert. 2004, 26, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, L.; Schouten, A.P.; Croes, E.A.J. Influencer Advertising on Instagram: Product-Influencer Fit and Number of Followers Affect Advertising Outcomes and Influencer Evaluations Via Credibility and Identification. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 41, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Fransen, M.L.; Van Noort, G.; Opree, S.J.; Vandeberg, L.; Reusch, S.; Van Lieshout, F.; Boerman, S.C. Effects of Disclosing Sponsored Content in Blogs. Am. Behav. Sci. 2016, 60, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żakowska-Biemans, S.; Pieniak, Z.; Kostyra, E.; Gutkowska, K. Searching for a Measure Integrating Sustainable and Healthy Eating Behaviors. Nutrients 2019, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Hudders, L.; Nelson, M.R. What is Influencer Marketing and how does it Target Children? A Review and Direction for Future Research. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Leong, S.M. The Ad Creativity Cube: Conceptualization and Initial Validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2007, 35, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sheinin, D.A.; Varki, S.; Ashley, C. The Differential Effect of Ad Novelty and Message Usefulness on Brand Judgments. J. Advert. 2011, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keyzer, F.; Dens, N.; De Pelsmacker, P. The Processing of Native Advertising Compared to Banner Advertising: An Eye-Tracking Experiment. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramova, Y.R.; de Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N. How Reading in a Foreign Vs. Native Language Moderates the Impact of Repetition-Induced Brand Placement Prominence on Placement Responses. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Neijens, P.C. Effects of Sponsorship Disclosure Timing on the Processing of Sponsored Content: A Study on the Effectiveness of European Disclosure Regulations. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorveld, H.A.M. Brand Communication in Social Media: A Research Agenda. J. Advert. 2019, 48, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Geuens, M.; Anckaert, P. Media Context and Advertising Effectiveness: The Role of Context Appreciation and Context/Ad Similarity. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keyzer, F.; Dens, N.; De Pelsmacker, P. The Impact of Relational Characteristics on Consumer Responses to Word of Mouth on Social Networking Sites. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2018, 23, 212–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, P.; Liebers, N. Greenfluencing the Impact of Parasocial Relationships with Social Media Influencers on Advertising Effectiveness and Followers’ Pro-Environmental Intentions. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; van Reijmersdal, E.A. Disclosing Influencer Marketing on YouTube to Children: The Moderating Role of Para-Social Relationship. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, K.; de Mooij, M. How ‘Social’ are Social Media? A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Online and Offline Purchase Decision Influences. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 20, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzeta, C.; De Keyzer, F.; Dens, N.; De Pelsmacker, P. Branded Content and Motivations for Social Media use as Drivers of Brand Outcomes on Social Media: A Cross-Cultural Study. Int. J. Advert. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, S.; Chwialkowska, A.; Hussain, N.; Bhatti, W.; Luomala, H. Cross-Cultural Perspective on Sustainable Consumption: Implications for Consumer Motivations and Promotion. Environ. Dev. Sustain 2023, 25, 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).