Does Entrepreneurship Policy Encourage College Graduates’ Entrepreneurship Behavior: The Intermediary Role Based on Entrepreneurship Willingness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypothesis

3.1. The Relationship between Entrepreneurship Policy and Entrepreneurship Behavior

3.2. The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurship Willingness

3.3. The Moderating Role of Awareness of Entrepreneurship Policies

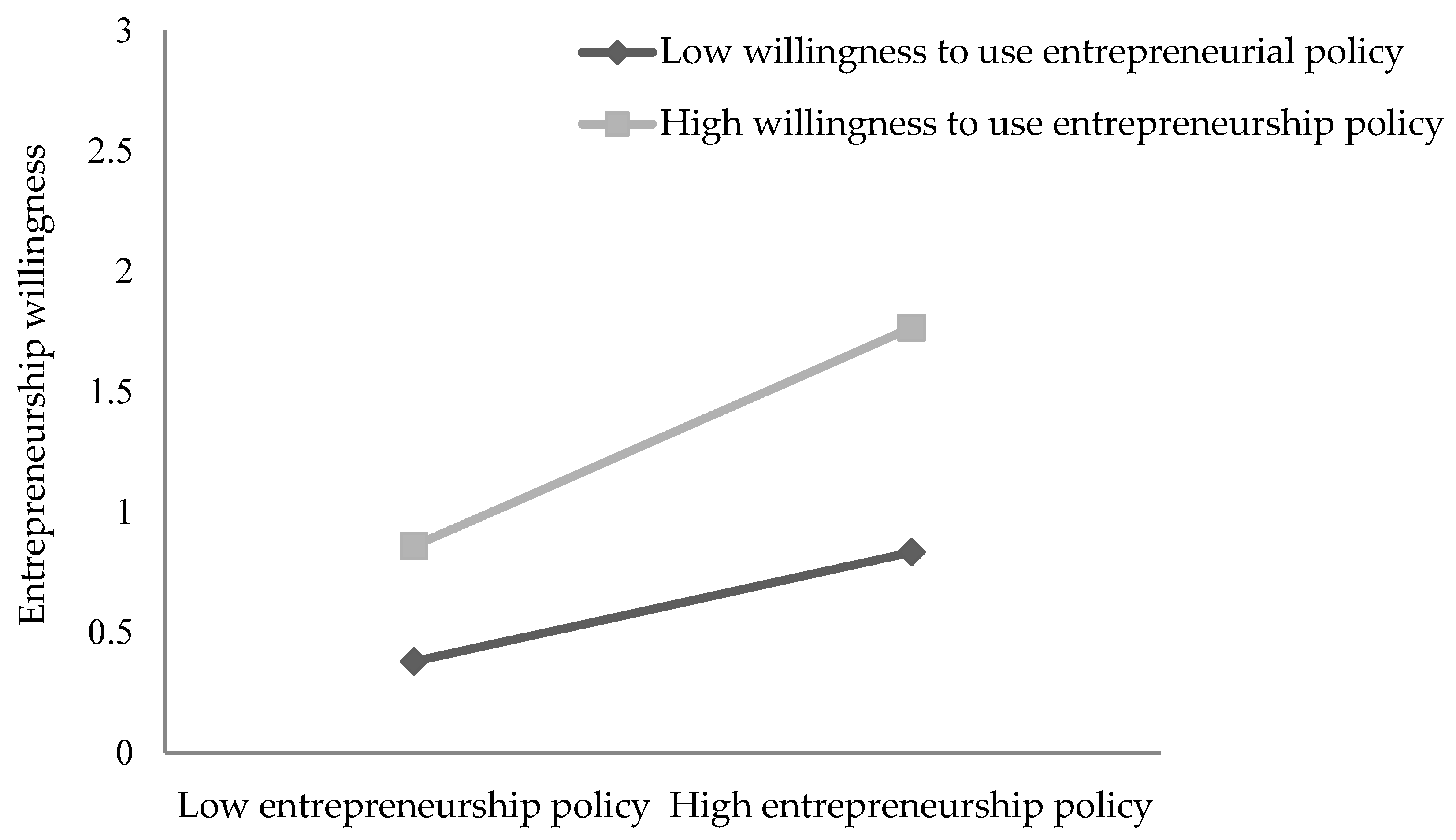

3.4. Moderating Role of Willingness to Use Entrepreneurship Policy

4. Research Design

4.1. Research Sample

4.2. Variable Design

4.3. Reliability and Validity Tests

4.4. Common Method Bias and Discriminant Validity Test

5. Hypothesis Testing

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Variables

5.2. Direct Effect of Entrepreneurship Policy and Mediating Effect of Entrepreneurship Willingness

5.3. Moderated Mediating Effect Test

6. Conclusions and Prospects

6.1. Research Conclusion

6.2. Research Implications

6.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, M.; Xu, H. A Review of Entrepreneurship Education for College Students in China. Adm. Sci. 2012, 2, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Gender on Entrepreneurial Intentions of University Students in the Visegrad Countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, J.M.; Congregado, E.; Román, C. The Value of an Educated Population for an Individual’s Entrepreneurship Success. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 29, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and Cross–Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtkoru, E.S.; Acar, P.; Teraman, B.S. Willingness to Take Risk and Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students: An Empirical Study Comparing Private and State Universities. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, W. Effects of Entrepreneurial Education on Intent to Open a Business. Front. Entrep. Res. 2001, 23, 112–113. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, L.; Lundstrom, A. Swedish Foundation for Small Business. Entrep. Policy. Future 2001, 16, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Lundström, A.; Stevenson, L. Entrepreneurship Policy—Definitions, Foundations and Framework. Entrep. Theory. Pract. 2005, 12, 41–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, J.A.; Altman, J.W. Creating Entrepreneurial Societies: The Role and Challenge for Entrepreneurship Education. J. Asia. Entrep. Sustain. 2005, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Degadt, J. For a More Effective Entrepreneurship Policy: Perception and Feedback as Preconditions. Entrep. Res. J. 2004, 5, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J. Cultural Diversity and Entrepreneurship: Policy Responses to Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Australia. Entrep. Region. Dev. 2003, 4, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astebro, T.; Bazzazian, N.; Braguinsky, S. Startups by Recent University Graduates and Their Faculty: Implications for University Entrepreneurship Policy. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.G., Jr.; Handler, W. Entrepreneurship and Family Business: Exploring the Connections. Entrep. Theory. Pract. 1994, 19, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.K.; Lee, S.H. An Exploratory Study of Techno entrepreneurial Intentions: A Career Anchor Perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 1, 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’ s Put the Person Back into Entrepreneurship Research: A Meta—Analysis on the Relationship Between Business Owners’ Personality Traits, Business Creation, and Success. Eur. J. Work. Org. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Evans, D.; Hanson, M. A Cross—Cultura Learning Strategy for Entrepreneurship Education: Outline of Key Concepts and Lessons Learned from a Comparative Study of Entrepreneurship Students in France and the US. Technovation 2003, 2, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do Entrepreneurship Programmes Raise Entrepreneurial Intention of Science and Engineering Students? The Effect of Learning, Inspiration and Resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 4, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B. Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas: The Case for Intention. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.M.; Gartner, W.B.; Reynolds, P.D. Exploring Start-up Event Sequences. J. Bus. Ventur. 1996, 11, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brice, J. The Role of Personality Dimensions and Occupational Preferences on The Formation of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Unpublished. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Management and Information Systems, Mississippi State University, Starkville, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial Potential and Potential Entrepreneurs. Soc. Sci. Elect. Pub. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, J.A. New Venture Creation: Entrepreneurship for 21 Century; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, H.; Dutta, S.; Oud, H. Determinants of Rural Industrial Entrepreneurship of Farmers in West Bengal: A Structural Equations Approach. Int. Regional. Sci. Rev. 2010, 33, 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dy, J.; Angela, M.; Martinez, S. Emancipation Through Digital Entrepreneurship? A Critical Realist Analysis. Org. Int. J. Org. Theor. Soc. 2018, 25, 585–608. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.H.; Lee, J.Y. The Impact of Entrepreneurship on Managerial Innovation Capacity: The Moderating Effects of Policy Finance and Management Support. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 51, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B. Developing and Governing Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: The Structure of Entrepreneurial Support Programs in Edinburgh, Scotland. Int. J. Innov. Reg. Dev. 2016, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouse, V.G.H. A Controlled Experiment Relating Entrepreneurial Education to Students’ Start-up Decisions. J. Small. Bus. Manag. 1990, 28, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Gruen, T.W.; Osmonbekov, T.; Czaplewski, A.J. How E-communities Extend the Concept of Exchange in Marketing: An Application of the Motivation, Opportunity, Ability (MOA) Theory. Mark. Theory 2005, 5, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, E.J. A Framework for Assessing Municipal High-Growth High-Technology Entrepreneurship Policy. Res. Policy 2021, 6, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KerriBrick, M.V.B. Risk Aversion: Experimental Evidence from South African Fishing Communities. Am. J. Agr. Econ. 2012, 94, 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Keuschnigg, C.; Nielsen, S.B. Tax Policy, Venture Capital, and Entrepreneurship. J. Public Econ. 2003, 87, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, M.; Mumin, S.; Zacca, C. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Willingness to Change, and Development Culture on New Product Exploration in Small Enterprises. J. Bus. Ind. Mark 2016, 31, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ribeiro, S.D.; Urbano, D. Socio-Cultural Factors and Entrepreneurial Activity: An Overview. Int. Small. Bus. J. 2011, 29, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallbone, D. Entrepreneurship Policy: Issues and Challenges. Small. Enterp. Res. 2016, 23, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.; Pennington, W.W. Organizational networks and the process of corporate entrepreneurship: How the motivation, opportunity, and ability to act affect firm knowledge, learning, and innovation. Small. Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, J.; Armitage, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: Ameta—Analytic Review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar]

- Min-Sun, K.; John, E.; Hunter, S. Relationships Among Attitudes, Behavioral Intentions, and Behavior a Meta-Analysis of Past Research. Commun. Res. 1993, 20, 331–364. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F.; Krueger, J.; Michael, D.; Alan, L. Competing Models of Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar]

- Adekiya, A.A.; Ibrahim, F. Entrepreneurship Intention among Students. The Antecedent Role of Culture and Entrepreneurship Training and Development. Int. J. Manage. Educ. 2016, 14, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azjen, I. “The Theory of Planned Behavior”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. J. Leisure. Res. 1991, 50, 176–211. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn, S.; Kushnirovich, N. The Impact of Policy on Immigrant Entrepreneurship and Businesses Practice in Israel. Int. J. Public. Sec. Manag. 2008, 21, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Shi, X. A Systematic Literature Review of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in Advanced and Emerging Economies. Small. Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.F. Monitoring the Success of Policy Initiatives to Increase Consumer Understanding of Financial Services. J. Financ. Regul. Compl. 2003, 11, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, K.D.; Nakos, G.; Dimitratos, P. Sme Entrepreneurial Orientation, International Performance, and the Moderating Role of Strategic Alliances. Entrep. Theory. Pract. 2015, 13, 1161–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Bai, X. On Information Selection Mechanism Among Government, Media and Public for Improving Government Credibility in China. C. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Management Science and Engineering 15th Annual Conference Proceedings, Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–12 September 2008; pp. 1834–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Petridou, E.; Mintrom, M. A Research Agenda for the Study of Policy Entrepreneurs. Policy. Stud. J. 2021, 49, 943–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, E.A.; Marie-Pierre, L.; Redican, K. Entrepreneurs’ Use of Internet and Social Media Applications. Telecommun. Policy 2017, 41, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, D.S.; Fuller, C.S.; Piano, E.E. Visions of Entrepreneurship Policy. J. Entrep. Public Policy 2018, 7, 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalkaka, R. Technology Business Incubators to Help Build an Innovation-Based Economy. J. Chang. Manag. 2002, 3, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Peng, W.; Xiong, N.N. The Effects of Fiscal and Tax Incentives on Regional Innovation Capability: Text Extraction Based on Python. Math 2020, 8, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M.J. The Changing Relationship Between Nonprofit Organizations and Public Social Service Agencies in the Era of Welfare Reform. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Quart. 2003, 32, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spill, R.L.; Licari, M.J.; Ray, L. Taking on Tobacco: Policy Entrepreneurship and the Tobacco Litigation. Polit. Res. Quart. 2001, 54, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Z.; Chen, C.; Chen, X.Z.; Min, X. The Influence of Entrepreneurial Policy on Entrepreneurial Willingness of Students: The Mediating Effect of Entrepreneurship Education and the Regulating Effect of Entrepreneurship Capital. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 592545. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Variables | Classified Items | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 51.4% |

| Female | 48.6% | |

| Academic qualifications | Specialist and below | 12.2% |

| Undergraduate | 49.7% | |

| Masters | 25.3% | |

| PhD | 12.8% | |

| Major | Science | 10.8% |

| Engineering | 12.2% | |

| Economics | 11.8% | |

| Management | 16.7% | |

| Literature | 5.9% | |

| Agronomy | 5.9% | |

| Medicine | 7.6% | |

| Law | 4.2% | |

| Pedagogy | 7.3% | |

| History | 6.6% | |

| Art | 7.3% | |

| Other | 3.8% |

| Primary Dimension | Secondary Dimension | Measurement Item |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship policy | Entrepreneurial finance and taxation financial policy | 1. The subsidies provided by the government for college graduates to start their own business (living, house purchase, and venue) helped me a lot |

| 2. Easy to successfully apply for small guaranteed loans or subsidized interest | ||

| 3. It is easier to apply for tax incentives for college graduates to start their own business | ||

| 4. There are various financing channels available for college graduates to start their own business | ||

| Entrepreneurship education and training policy | 5. Theoretical knowledge courses of entrepreneurship education in colleges and universities help me a lot | |

| 6. The government’s entrepreneurial training has helped me a lot | ||

| 7. The guidance of the team of entrepreneurial experts was very helpful to me | ||

| Entrepreneurship platform policy | 8. Entrepreneurial services network and other information technology platform has helped me a lot | |

| 9. It is easier to apply for admission to a college student business park or business incubation base | ||

| 10. The government provided business project promotion and incubation, which helped me a lot | ||

| Entrepreneurship willingness | —— | 1. I am ready to do anything to become an entrepreneur |

| 2. My career goal is to become an entrepreneur | ||

| 3. I will make every effort to start and run my own business | ||

| 4. I decided to start a business in the future | ||

| 5. I have seriously considered starting a business | ||

| 6. I have a firm will to start a business someday | ||

| Awareness of entrepreneurship policy | Awareness of entrepreneurial finance, taxation, and financial policy | 1. I understand the various business subsidies issued by the government |

| 2. I understand the application of guaranteed loans and interest subsidies for business start-ups | ||

| 3. I understand the strength and scope of tax incentives | ||

| 4. I understand the financing channels provided by the government for business start-up capital | ||

| Awareness of entrepreneurship education and training policy | 5. I understand the school’s entrepreneurship education curriculum | |

| 6. I understand the entrepreneurial training conducted by the government | ||

| 7. I understand the guidance service of the expert team | ||

| Awareness of entrepreneurship platform policy | 8. I understand the construction of entrepreneurial services networks and other information technology platforms | |

| 9. I understand the construction of business parks and business incubation bases | ||

| 10. I understand the promotion and incubation of entrepreneurial projects | ||

| Willingness to use Entrepreneurship policy | —— | 1. I am interested in entrepreneurship policy |

| 2. I think the entrepreneurship policy is helpful to my entrepreneurial process | ||

| 3. Before using the policy, I will fully understand the content of the policy | ||

| 4. Before using the policy, I will fully consider my actual situation | ||

| Entrepreneurship behavior | —— | 1. I can identify valuable market opportunities very well |

| 2. I can help everyone to start a business | ||

| 3. When starting a business, I can actively seek new resources to make up for the lack of existing resources | ||

| 4. I pay much attention to establishing a good relationship with the technical service team and technical experts | ||

| 5. I tend to learn from the management experience and system of successful entrepreneurs |

| Variables | Dimension | Number of Projects | Reliability Tests | KMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s | Alpha | ||||

| Entrepreneurship policy | Entrepreneurial finance and taxation financial policy | 4 | 0.890 | 0.942 | 0.919 |

| Entrepreneurship education and training policy | 3 | 0.823 | |||

| Entrepreneurship platform policy | 3 | 0.801 | |||

| Awareness of entrepreneurship policy | Awareness of entrepreneurial finance, taxation, and financial policy | 4 | 0.908 | 0.950 | 0.933 |

| Awareness of entrepreneurship education and training policy | 3 | 0.834 | |||

| Awareness of entrepreneurship platform policy | 3 | 0.829 | |||

| Willingness to use Entrepreneurship policy | 4 | 0.864 | 0.762 | ||

| Entrepreneurship willingness | 6 | 0.913 | 0.856 | ||

| Entrepreneurship behavior | 5 | 0.889 | 0.825 | ||

| Variables | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.49 | 0.50 | 1 | |||||||

| Academic qualifications | 2.39 | 0.86 | 0.053 | 1 | ||||||

| Major | 5.47 | 3.37 | 0.016 | −0.007 | 1 | |||||

| Entrepreneurship policy | 3.68 | 0.87 | 0.112 | 0.066 | 0.008 | 1 | ||||

| Entrepreneurship willingness | 3.66 | 0.93 | 0.091 | −0.052 | −0.052 | 0.522 ** | 1 | |||

| Awareness of entrepreneurship policy | 3.73 | 0.88 | 0.053 | −0.062 | −0.047 | 0.354 ** | 0.471 ** | 1 | ||

| Willingness to use Entrepreneurship policy | 3.68 | 0.90 | 0.051 | 0.056 | −0.025 | 0.401 ** | 0.549 ** | 0.410 ** | 1 | |

| Entrepreneurship behavior | 3.65 | 0.91 | 0.071 | 0.019 | −0.032 | 0.591 ** | 0.631 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.555 ** | 1 |

| Variable Category | Variable Name | Entrepreneurship Willingness | Entrepreneurship Behavior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||

| Constant term | 3.457 *** | 2.119 *** | 3.464 *** | 1.453 *** | 1.528 *** | 0.640 * | |

| Control variable | Gender | 0.087 | 0.009 | 0.128 | 0.011 | 0.08 | 0.008 |

| Academic qualifications | 0.056 | 0.031 | 0.016 | −0.022 | −0.015 | −0.034 | |

| Major | −0.007 | −0.008 | −0.009 | −0.010 | −0.005 | −0.007 | |

| Independent variable | Entrepreneurship policy | 0.412 *** | 0.620 *** | 0.462 *** | |||

| mediating variable | Entrepreneurship willingness | 0.560 *** | 0.384 *** | ||||

| R2 | 0.006 | 0.163 | 0.006 | 0.351 | 0.310 | 0.472 | |

| R2 | 0.006 | 0.157 | 0.006 | 0.345 | 0.304 | 0.120 | |

| F | 0.582 | 13.748 *** | 0.605 | 38.338 *** | 31.823 *** | 50.326 *** | |

| F | 52.929 *** | 150.580 *** | 124.685 *** | 64.091 *** | |||

| Variable Category | Variable Name | Entrepreneurship Willingness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | ||

| Constant term | 3.457 *** | 2.119 | 1.279 *** | 1.176 *** | 1.279 *** | 0.960 ** | |

| Control variable | Gender | 0.087 | 0.009 | −0.023 | −0.026 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| Academic qualifications | 0.056 | 0.031 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.059 | 0.057 | |

| Major | −0.007 | −0.008 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.003 | −0.002 | |

| Independent variable | Entrepreneurship policy | 0.412 *** | 0.154 ** | 0.169 ** | 0.297 *** | 0.340 *** | |

| Moderating variable | Awareness of entrepreneurship policy | 0.462 *** | 0.474 *** | ||||

| Willingness to use entrepreneurship policy | 0.319 *** | 0.353 *** | |||||

| Moderating effects | Entrepreneurship policy * Awareness of entrepreneurship policy | 0.027 | |||||

| Entrepreneurship olicy * willingness to use entrepreneurship policy | 0.113 * | ||||||

| R2 | 0.006 | 0.163 | 0.324 | 0.325 | 0.246 | 0.261 | |

| R2 | 0.006 | 0.157 | 0.162 | 0.001 | 0.083 | 0.014 | |

| F | 0.582 | 13.748 *** | 27.069 *** | 22.564 *** | 18.410 *** | 16.500 *** | |

| F | 52.929 *** | 67.440 *** | 0.353 | 31.189 *** | 5.489 * | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, D.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Does Entrepreneurship Policy Encourage College Graduates’ Entrepreneurship Behavior: The Intermediary Role Based on Entrepreneurship Willingness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129492

Meng D, Shang Y, Zhang X, Li Y. Does Entrepreneurship Policy Encourage College Graduates’ Entrepreneurship Behavior: The Intermediary Role Based on Entrepreneurship Willingness. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129492

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Dongni, Yingying Shang, Xiaoxu Zhang, and Ying Li. 2023. "Does Entrepreneurship Policy Encourage College Graduates’ Entrepreneurship Behavior: The Intermediary Role Based on Entrepreneurship Willingness" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129492

APA StyleMeng, D., Shang, Y., Zhang, X., & Li, Y. (2023). Does Entrepreneurship Policy Encourage College Graduates’ Entrepreneurship Behavior: The Intermediary Role Based on Entrepreneurship Willingness. Sustainability, 15(12), 9492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129492