Indicators, Strategies, and Rule Settings for Sustainable Public–Private Infrastructure Partnerships: From Literature Review towards Institutional Designs

Abstract

1. Introduction

- is too little consensus on the delineation of sustainability process principles and their indicators, both for environmental and social sustainability.

- are inconsistencies in various checklists used for the various environmental and social sustainability outcome principles and their indicators

- is a need for knowledge on appropriate institutional frameworks that can foster sustainable PPPs at the planning stages.

- Which outcome indicators regarding infrastructure-related sustainability concerns are addressed in the literature, both about environmental and social sustainability?

- Which process-steering strategies and indicators guiding towards the envisioned sustainable PPPs are addressed in the literature, both about environmental and social sustainability?

- How can the effective employment of applied steering strategies in the planning stages of PPPs be connected to institutional rule settings in a principal governance framework?

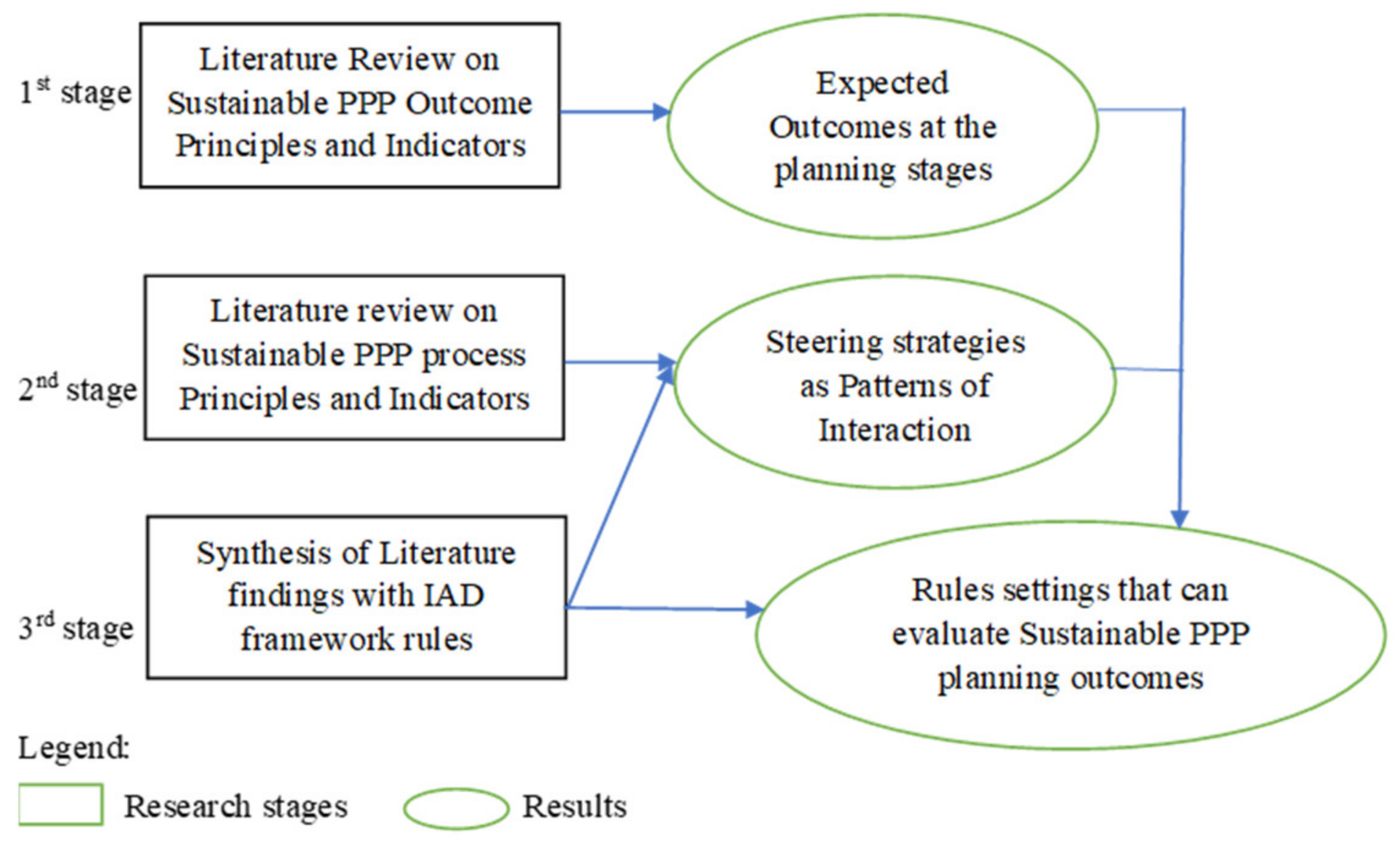

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

2.1.1. Search Strategy

2.1.2. Selection of Articles

| Search Steps | Keyword String | Wiley | Springer | Taylor & Francis | Emerald | MDPI | Elsevier | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Title-ABS-KEY (Sustainable PPPs) | 8087 | 2301 | 6453 | 644 | 95 | 13,428 | 31,008 |

| 2 | Restriction of search to English journal articles | 6642 | 491 | 5549 | 444 | 86 | 9264 | 22,476 |

| 3 | Restriction of search to recent studies (from 2013 to 2022) | 3475 | 369 | 3087 | 365 | 84 | 6219 | 13,599 |

| 4 | Exclusion of irrelevant subject areas | 159 | 106 | 109 | 165 | 45 | 170 | 754 |

| 5 | Study of titles, abstracts, and details of the articles. | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 32 |

2.1.3. Analysis and Synthetization

2.1.4. Limitations

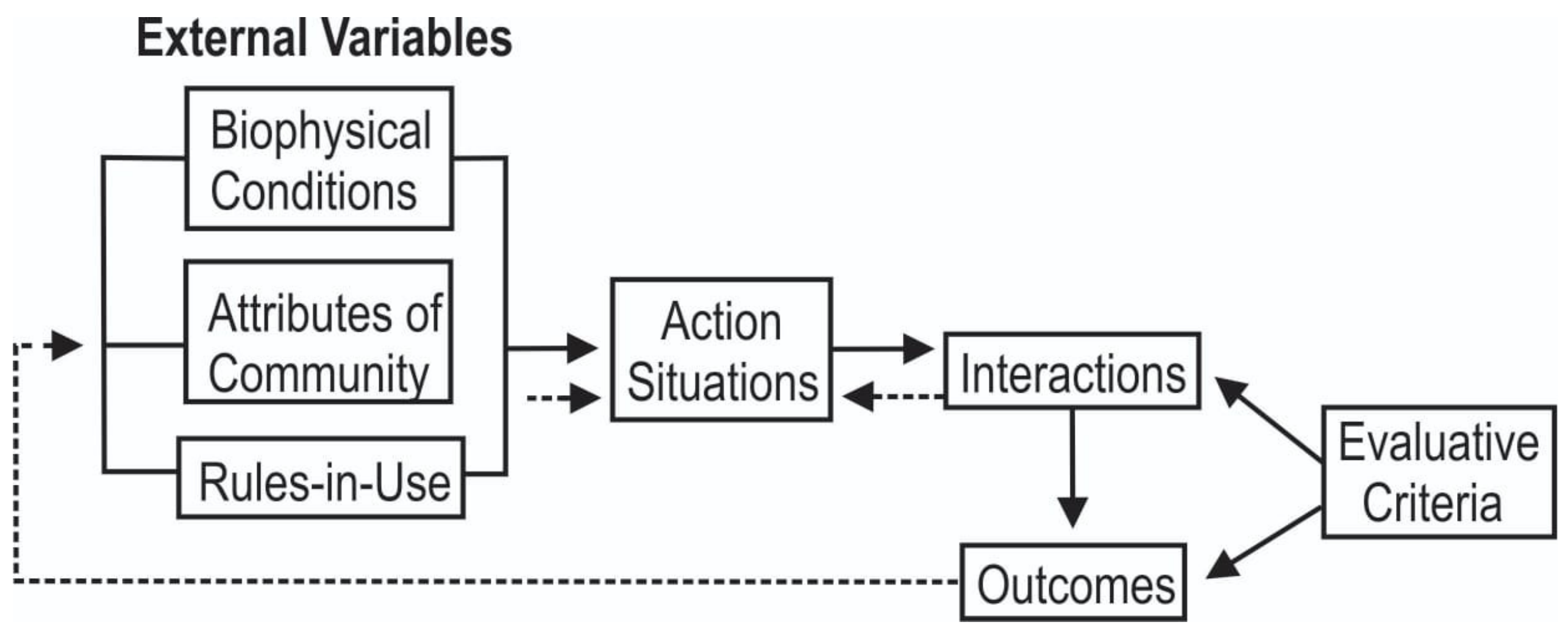

2.2. Analytical Framework

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sustainability Outcome Principles and Indicators

| Sustainability Pillar | Outcome Principles | Indicators | Examples | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Efficient Project Implementation | Clean Air | Measures reducing CO2 emissions | Bakhtawar et al. [17], Patil et al. [19], Hoeft et al. [30]. |

| Noise Level | Measures reducing noise vibrations | Lenferink et al. [7], Sweere [29], Hoeft et al. [30]. | ||

| Water | Water protection (less use of water) and quality | Patil et al. [19], He et al. [22], Sweere [29]. | ||

| Ecological Compatibility | Biodiversity | Protection of fauna and flora | Berrone et al. [6], Sweere [29], Hoeft et al. [30]. | |

| Landscape Conservation | Efficient land use; Conserving or replanting trees and vegetation | Bakhtawar et al. [17], Sweere [29], Hoeft et al. [30]. | ||

| Resource Utilization Efficiency and Maintenance | Material and Design | Environmental friendly materials, contextual fit in the environment, innovation, multi-functional design, local materials | Hueskes et al. [3], Koppenjan [4], He et al. [22]. | |

| Energy | Use of renewable energy and efficiency | Hueskes et al. [3], Patil et al. [19], Sweere [29] | ||

| Social | Stakeholders Empowerment | Participation and Co-creation | Citizens and stakeholders involved in the decision making | Koppenjan [4], He et al. [22] |

| Education and Training | Capacity-building measures | Xiahou et al. [55], Wang et al. [56]. | ||

| Quality of Life | Health and Safety | Construction site safety management and management | Bakhtawar et al. [17], Patil et al. [19], Wang et al. [56]. | |

| Local and Societal Needs | Meeting the demands of the local community | Berrone et al. [6], Boström [53], Wang et al. [56]. | ||

| Social Justice | Emancipation and Equity (inclusiveness) | Accessibility for people with disabilities; affordability; promoting diversity; inclusion | Berrone et al. [6] Patil et al. [19], Xiahou et al. [55], | |

| Labor and Human Rights | Labor rights, non-discrimination, local employment | Patil et al. [19], Boström [53], Wang et al. [56]. | ||

| Public Meeting | Measures that stimulate social cohesion | Berrone et al. [6], Wang et al. [56]. |

3.1.1. Overview of Environmental Sustainability Outcome Indicators in the Literature

| Study | Efficient Project Implementation | Ecological Compatibility | Resource Utilization Efficiency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOI 1 | EOI 2 | EOI 3 | EOI 4 | EOI 5 | EOI 6 | EOI 7 | Sum | |

| Xiahou et al. [55] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Hoeft et al. [30] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Bakhtawar et al. [17] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Patil et al. [59] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Nizkorodov [60] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Schahbaz et al. [61] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Khan et al. [58] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Li et al. [62] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Berrone et al. [6] | X | X | X | 3 | ||||

| Chen et al. [63] | X | X | X | X | 4 | |||

| Dolla and Laishram [64] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Yaun et al. [65] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Gao [66] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Malvestio et al. [16] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Agarchand and Laishram [67] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Kivila et al. [68] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Spraul and Thaler [69] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Cedrick [70] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Koscielniak and Gorka [71] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Patil and Laishram [19] | X | X | X | 3 | ||||

| Villabo-Romero et al. [72] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Sum | 15 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 52 |

3.1.2. Overview of Social Sustainability Outcome Indicators in the Literature

| Study | Stakeholder’s Empowerment | Quality of Life | Social Justice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOI 1 | SOI 2 | SOI 3 | SOI 4 | SOI 5 | SOI 6 | SOI 7 | Sum | |

| Xiahou et al. [55] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Hoeft et al. [30] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Bakhtawar et al. [17] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Patil et al. [59] | X | X | X | 3 | ||||

| Wang et al. [56] | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | |

| Selim and Elgohary [74] | X | X | X | X | 4 | |||

| Xiong et al. [75] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Spoann et al. [76] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Berrone et al. [6] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 |

| Spraul and Thaler [69] | X | X | X | 3 | ||||

| Li et al. [62] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Chen et al. [63] | X | X | X | 3 | ||||

| Yuan et al. [65] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Gao [66] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Malvestio et al. [16] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Agarchand and Laishram [67] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Patil and Laishram [19] | X | X | X | X | 4 | |||

| Villabo-Romero et al. [72] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Lenferink et al. [7] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Ng et al. [77] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| 12 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 60 |

3.1.3. Summary

3.2. Sustainability Process Principles Indicators and Strategies

| Sustainability Pillar | Process Principles | Indicators | Steering Strategies | Sources | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Sustainability | Prepare | Assessment of Environmental Impacts and Mitigation Options | Evidence towards EIA for better life-cycle performance (ESS 1). | Koppenjan [4], Shahbaz et al. [61] | Proof that guidelines towards EIA are applied i.e., conforming contractors to systems engineering standards such as ISO 15288 |

| Support Systems and Schemes are used | Incentives or subsidies to private partners that can provide more environmental sustainability expertise (ESS 2). | Bakhtawar et al. [17], Patil and Laishram [19] | Involved public-private actors show that they use incentives maximally to connect environmental expertise. | ||

| Available Environmental Policy | Liability and compensation for environmental impacts (ESS 3). | Berrone et al. [6], Grasman et al. [79] | Public-private actors are aware of environmental regulations and amend their behavior accordingly to avoid environmental externalities and liabilities. | ||

| Procure | Awareness of Environmental Sustainability Criteria explicit to Project and Location. | Additional points are given to bids that include innovation related to the reduction of environmental problems (ESS 4). | Hueskes et al. [3], Patil and Laishram [19], Grasman et al. [79] | Award criteria are not based on price alone but on quality, and avoiding environmental externalities i.e., by application of MEAT criteria (Most Economically Advantageous Tender). | |

| Competition on Environmental Sustainability Criteria | Prequalification is based on experience in environmental sustainability practices as demonstrated by relevant certifications (ESS 5). | [19], Dolla and Laishram [64] Yaun et al. [66] | Terms of reference that focus on proven expertise or skills in environmental sustainability practices. | ||

| Multi-actor Dialogue | Active involvement of environmental civil groups in judging the bids (ESS 6) | Leferink et al. [7], Grasman et al. [79] | Involvement of stakeholders and outside expertise in the procurement process. | ||

| Contract | Procedure to Monitor and Revise the Contract | Contract review provision in between and updating agreements to do justice to new technological findings, and socio-economic and political realities (ESS 7). | Koppenjan [4], Berrone et al. [6], Patil et al. [59] | Contracts are monitored periodically and procedures are in place to revise the contract, settle disputes and terminate the contract. | |

| Social Sustainability | Prepare | Efforts on Assessing Social Impacts on the Local Community. | Assessment tools for stakeholders’ participation such as building information modeling (SSS 1). | Bakhtawar et al. [17], Hoeft et al. [30], Li et al. [62] | Use of impact analysis and simulation techniques to highlight probabilistic risks |

| Inclusion of Stakeholders through a Special-purpose Company | A special purpose company that is jointly owned by the government, users, and private developers for the development of PPP projects as an alternative institutional mechanism (SSS 2). | Berrone et al. [6], Gao [66], Xiong et al. [75] | An external board that can deepen sustainability at the planning stages. | ||

| Community Involvement through Participation | Use of two-way communication in participative forms (SSS 3). | Xiahou et al. [55], Selim [74] Bai et al. [76] | Project information is freely available for instance, activities are organized to involve the local community to comment and connect online | ||

| Procure | Clear Bid Strategy | A platform for close debate during the bidding stage via a strategic communication plan as part of the procurement policy (SSS 4). | Patil et al. [59], Gao [66] | The tender document defines the service standard to be achieved especially the impact and risks related to the community. | |

| 3rd Party Probity Arrangements | Fairness and process auditors are appointed as third-party experts to monitor the procurement process (SSS5). | Berrone et al. [6], Hoeft et al. [30] | The third-party review takes place and it is taken seriously. | ||

| Project Scrutiny | An independent and technical review panel that can scrutinize the PPP project and safeguard sustainability during the bidding process (SSS 6). | Wang et al. [56], Yaun et al. [65] | A panel of experts in charge of reviewing the candidates, especially their efforts at minimizing impact and risks on the local community | ||

| Contract | The Contract is Finalized based on the Relationship among Stakeholders. | Main contractor-subcontractor relationships (SSS 7). | Berrone et al. [6], Patil and Laishram [19], and Gao [66] | The process to monitor and adjust the contract to integrate expertise, information, and insights. |

3.2.1. Environmental Sustainability Process Principles Indicators and Strategies in the Literature

| Study | Prepare | Procure | Contract | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESPI 1 | ESPI 2 | ESPI 3 | ESPI 4 | ESPI 5 | ESPI 6 | ESPI 7 | Sum | |

| Hoeft et al. [30] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Patil et al. [59] | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | |

| Nizkorodov [60] | X | X | X | X | 4 | |||

| Khan et al. [58] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Schahbaz et al. [61] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Selim and El-Gohary [74] | X | X | X | 3 | ||||

| Chen et al. [63] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Spoann et al. [76] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Berrone et al. [6] | X | X | X | 3 | ||||

| Gao [66] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Malvestio et al. [16] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Dolla and Laishram [64] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Kivila et al. [68] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Agarchand and Laishram [67] | X | X | X | X | 4 | |||

| Cedrick [70] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Ruis et al. [80] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Patil amd Laishram [19] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Villabo-Romero et al. [72] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Koppenjan [4] | X | X | X | X | 4 | |||

| Lenferink et al. [7] | X | X | X | X | 4 | |||

| 6 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 50 |

3.2.2. Social Sustainability Process Principles Indicators and Strategies in the Literature

| Study | Prepare | Procure | Contract | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSPI 1 | SSPI 2 | SSPI 3 | SSPI 4 | SSPI 5 | SSPI 6 | SSPI 7 | Sum | |

| Hoeft et al. [30] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Nizkorodov [60] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Patil et al. [59] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 |

| Bakhtawar et al. [17] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Wang et al. [56] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Selim and Elgohary [73] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Xiong et al. [74] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Berrone et al. [6] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Yaun et al. [65] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Gao [66] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Dolla and Laishram [64] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Agarchand and Laishram [67]. | X | X | X | X | 4 | |||

| Kivila et al. [68] | X | X | 2 | |||||

| Patil and Laishram [19] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Koppenjan [4] | X | 1 | ||||||

| Ng et al. [77] | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| Lenferink et al. [7] | X | X | X | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 43 |

3.2.3. Summary

3.3. Overview

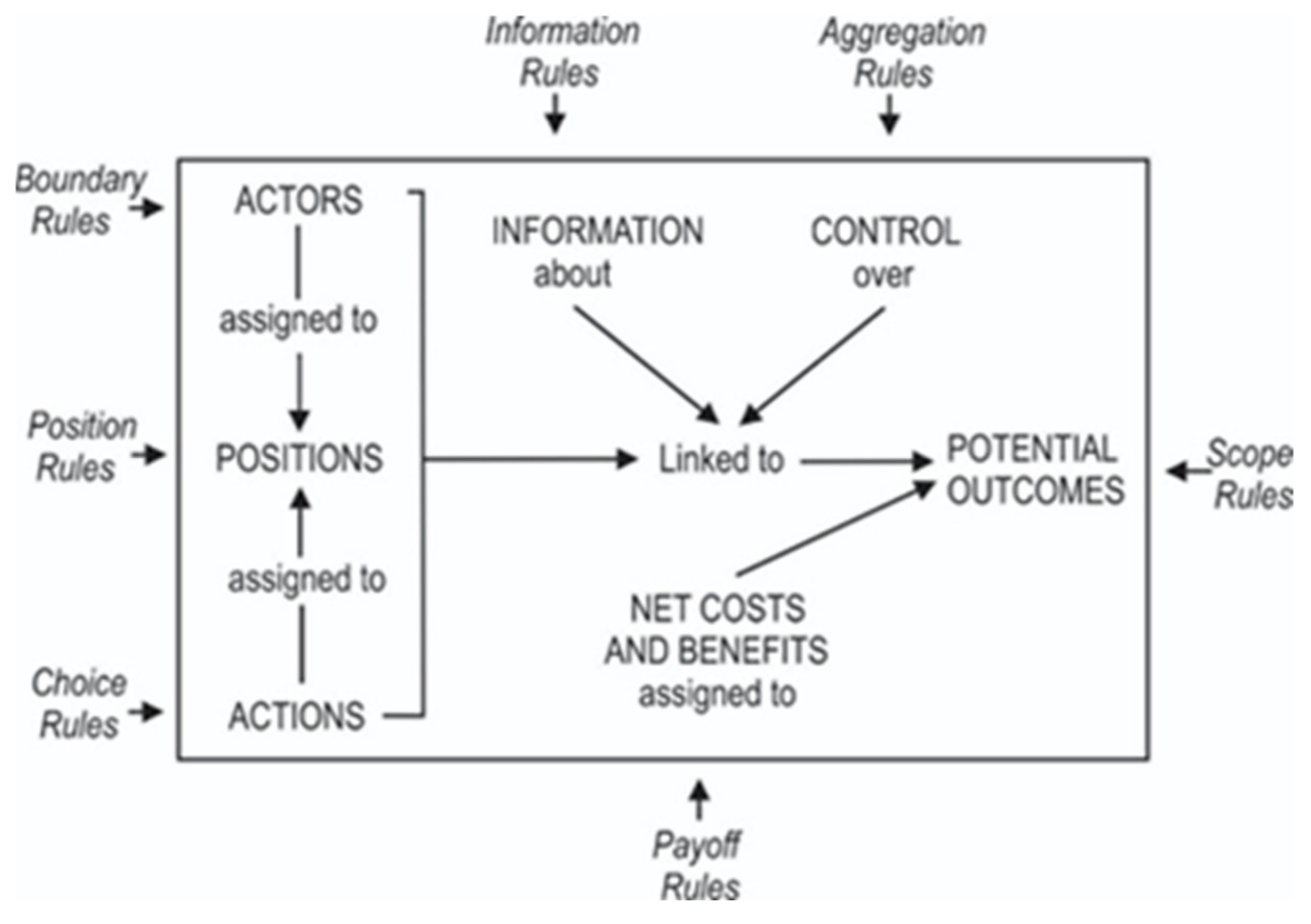

4. Rule Setting for Sustainable PPPs

| Type of Rule | Function of Rules | ESS and SSS, Rule Settings, and Functioning of Rules (As Regards Sustainable PPPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Position | “Create positions (e.g., member, judge, voter, representative) that actors may hold”. | ESS and SSS in Table 9 align to one or more of these three rule functions target, with sustainable PPPs in mind, (i) the configuration of actor positions in action situations as regards PPPs, (ii) the characteristics of involved actors in terms of cognitions, motivations, and resources, i.e., what the involved actors may know, strive for, and capable of and (iii), how they come into or exit from the action situation, what they must and can undertake in the (collective) action situation. |

| Boundary | “Define (1) who is eligible to hold a certain position, (2) the process by which positions are assigned to actors (including rules of succession), and (3) how positions may be exited”. | |

| Choice | “Prescribe actions actors in position must, must not, or may take in various circumstances”. | |

| Aggregation | “Determine how many, and which, players must participate in a given collective or operational-choice decision”. | ESS and SSS in Table 9 align to one or more of these two rule functions targeted with sustainable PPPs in mind (i) how many and which actors are involved and (ii) how data, information and knowledge gathering, and processing as regards environmental and social sustainability should be taken aboard. |

| Information | “Authorize channels of information flows available to participants, including assignation of obligations, permissions, or prohibitions on communication”. | |

| Pay-off | “Assign rewards or sanctions to particular actions that have been taken or on outcomes”. | ESS and SSS in Table 9 aligned to one or more of these two rule functions target with sustainable PPPs in mind (i) to what extent impacts upon environmental and social sustainability of projects can be neglected and (ii) what the consequences imposed upon actors, action situation and decisions can be. |

| Scope | “Delimit the range of possible outcomes. In the absence of a scope rule, actors can affect any physically possible outcomes”. |

| Ostrom Rule Types | Action Situation (Preparation) | Action Situation (Procurement) | Action Situation (Contract) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESS | SSS | ESS | SSS | ESS | SSS | |

| Position– Boundary–Choice | SSS 2 | ESS 5 | SSS 5 SSS 6 | ESS 7 | ||

| Scope–Payoff | ESS 2 | ESS 4 | SSS 7 | |||

| Information– Aggregation | ESS 1 ESS 3 | SSS 1 SSS 3 SSS 4 | ESS 6 | |||

- Obligingness with extant environmental and social sustainability rules and strategies;

- Government stimulus on the long-term stability of PPPs;

- Contexts and benchmarks for the entry of private partners into PPP;

- Competitive bidding system for PPP contracts;

- Supervision and regulation of EIA and the Social Impact Assessment;

- Entrance and assurance to the private sector regarding the right to enter and be dynamic in partnerships with the contracting authority;

- Role of the public sector, including the transfer of decision making.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M.K. Public-Private Partnerships: The Worldwide Revolution in Infrastructure Provision and Project Finance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2004; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Woetzel, J.; Garemo, N.; Mischke, J.; Hjerpe, M.; Palter, R. Bridging Global Infrastructure Gaps. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/bridging-global-infrastructure-gaps (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. Governing Public-Private Partnerships for Sustainability: An Analysis of Procurement and Governance Practices of PPP Infrastructure Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.F. Public-Private Partnerships for Green Infrastructures. Tensions and Challenges. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 12, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Akintoye, A. An Overview of Public–Private Partnership. In Public–Private Partnerships: Managing Risks and Opportunities; Akintoye, A., Beck, M., Hardcastle, C., Eds.; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Berrone, P.; Ricart, J.E.; Duch, A.I.; Bernardo, V.; Salvador, J.; Piedra Peña, J.; Rodríguez Planas, M. EASIER: An Evaluation Model for Public–Private Partnerships Contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenferink, S.; Tillema, T.; Arts, J. Towards Sustainable Infrastructure Development through Integrated Contracts: Experiences with Inclusiveness in Dutch Infrastructure Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, P. The Challenging Business of Long-Term Public-Private Partnerships: Reflections on Local Experience. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.F.; Enserink, B. Public–Private Partnerships in Urban Infrastructures: Reconciling Private Sector Participation and Sustainability. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamonia, N. Improving the Coverage Area of Drinking Water Provision by Using Build Operate and Transfer Investments in Indonesia: An Institutional Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, A. Public-Private Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Exploring Their Design and Its Impact on Effectiveness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayllar, M.R. Public-Private Partnerships in Hong Kong: Good Governance–The Essential Missing Ingredient? Aust. J. Public Adm. 2010, 69, S99–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos-Castaño, J.; Mahalingam, A.; Dewulf, G. Unpacking the path-dependent process of institutional change for PPPs. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2014, 73, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochańczyk-Kupka, D.; Pęciak, R. Institutions in the Context of Sustainable Development. Macrotheme Rev. 2015, 4, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.M. Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Int. Soc. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Malvestio, A.C.; Fischer, T.B.; Montaño, M. The Consideration of Environmental and Social Issues in Transport Policy, Plan and Programme Making in Brazil: A Systems Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 674–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtawar, B.; Thaheem, M.J.; Arshad, H.; Tariq, S.; Mazher, K.M.; Zayed, T.; Akhtar, N. A Sustainability-Based Risk Assessment for P3 Projects Using a Simulation Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colverson, S.; Perera, O. Harnessing the Power of Public-Private Partnerships: The Role of Hybrid Financing Strategies in Sustainable Development. 2012. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/harnessing_ppp.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Patil, N.A.; Laishram, B. Public-Private Partnerships from Sustainability Perspective—A Critical Analysis of the Indian Case. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2016, 16, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, A.; Jones, M.; O’Mahony, T.; Byrne, G. Selecting Environmental Indicators for Use in Strategic Environmental Assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Muench, S.T. Sustainability Trends Measured by the Greenroads Rating System. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2357, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. Critical Factors to Achieve Sustainability of Public-Private Partnership Projects in the Water Sector: A Stakeholder-Oriented Network Perspective. Complexity 2020, 2020, 8895980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, A.; Caño, A.D.; de la Cruz, M.P.; Gómez, D.; Josa, A. Sustainability Assessment of Concrete Structures within the Spanish Structural Concrete Code. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 138, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, O.O.; Kumaraswamy, M.M.; Wong, A.; Ng, S.T. Sustainability Appraisal in Infrastructure Projects (SUSAIP): Part 2: A Case Study in Bridge Design. Autom. Constr. 2006, 15, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Tam, E.K. Indicators and Framework for Assessing Sustainable Infrastructure. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2005, 32, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C. Sustainability Appraisal for Sustainable Development: Integrating Everything from Jobs to Climate Change. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2001, 19, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.B.; Selma, H.; Susan, H.; James, T.; Graham, W. Sustainability Assessment: Criteria and Processes; Earthscan Publication: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Devolder, S.; Block, T. Transition Thinking Incorporated: Towards a New Discussion Framework on Sustainable Urban Projects. Sustainability 2005, 7, 3269–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweere, N. An Energy-Neutral Highway, the New Standard? Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeft, M.; Pieper, M.; Eriksson, K.; Bargstädt, H.-J. Toward Life Cycle Sustainability in Infrastructure: The Role of Automation and Robotics in PPP Projects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarez, R.P.F.; Vargas, R.V.; Alvarenga, J.C.; Chinelli, C.K.; de Almeida Costa, M.; de Oliveira, B.L.; Soares, C.A.P. Sustainability Indicators to Assess Infrastructure Projects: Sector Disclosure to Interlock with the Global Reporting Initiative. Eng. J. 2020, 24, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, S.; McNamara, N.; Acholo, M.; Okwoli, B. Sustainability Indicators: The Problem of Integration. Sustain. Dev. 2001, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, M.M.; Anvuur, A.M. Selecting Sustainable Teams for PPP Projects. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge using Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.J.; Mulrow, C.D.; Haynes, R.B. Systematic Reviews: Synthesis of Best Evidence for Clinical Decisions. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 126, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, P.T.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R. Taxonomy of Risks in PPP Transportation Projects: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 22, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies that Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W-65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seuring, S.; Gold, S. Conducting Content-Analysis Based Literature Reviews in Supply Chain Management. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 17, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Nilsson, F. Themes and Challenges in Making Supply Chains Environmentally Sustainable. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 17, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Liane Easton, P. Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Evolution and Future Directions. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. 2011, 41, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Kukah, A.S. Public-Private Partnerships for Sustainable Infrastructure Development in Ghana: A Systematic Review and Recommendations. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2021, 12, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauko, T. An Institutional Analysis of Property Development, Good Governance, and Urban Sustainability. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 2053–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polski, M.M.; Ostrom, E. An Institutional Framework for Policy Analysis and Design. In Proceedings of the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Center for the Study of Institutions, Population, and Environmental Change, Department of Political Science Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, 21–25 June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.H. Laws, Norms, and the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. J. Inst. Econ. 2017, 13, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, M.T.; Yandle, T. Taking Institutions Seriously: Using the IAD Framework to Analyze Fisheries Policy. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S.E.; Ostrom, E. A Grammar of Institutions. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1995, 89, 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J.; Walker, J. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 186–215. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Towards Sustainable Development: Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Boström, M. A Missing Pillar? Challenges in Theorizing and Practicing Social Sustainability: Introduction to the Special Issue. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.Y.; Chang, A.S. Framework for Developing Construction Sustainability Items: The Example of Highway Design. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 20, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiahou, X.; Tang, L.; Yuan, J.; Zuo, J.; Li, Q. Exploring Social Impacts of Urban Rail Transit PPP Projects: Towards Dynamic Social Change from the Stakeholder Perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 93, 106700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Liu, T.; Sankaran, S. Social Sustainability in Public–Private Partnership Projects: Case Study of the Northern Beaches Hospital in Sydney. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 29, 2437–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.A.; Tharun, D.; Laishram, B. Infrastructure Development through PPPs in India: Criteria for Sustainability Assessment. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 708–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Ali, M.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Wahab, S.; Jiao, Z. The Impact of Technological Innovation and Public-Private Partnership Investment on Sustainable Environment in China: Consumption-Based Carbon Emissions Analysis. Sustain. Develop. 2020, 28, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.A.; Thounaojam, N.; Laishram, B. Enhancing Sustainability of Indian PPP Procurement Process using System Dynamics Model. J. Public Procure. 2021, 21, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizkorodov, E. Evaluating Risk Allocation and Project Impacts of Sustainability-Oriented Water Public-Private Partnerships in Southern California: A Comparative Case Analysis. World Dev. 2021, 140, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Raghutla, C.; Song, M.; Zameer, H.; Jiao, Z. Public-Private Partnerships Investment in Energy as New Determinant of CO2 Emissions: The Role of Technological Innovations in China. Energy Econ. 2020, 86, 104664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xia, Q.; Wang, L.; Ma, Y. Sustainability Assessment of Urban Water Environment Treatment Public-Private Partnership Projects using Fuzzy Logic. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2020, 18, 1251–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yu, Y.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C.; Xu, J. Developing a Project Sustainability Index for Sustainable Development in Transnational Public-Private Partnership Projects. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolla, T.; Laishram, B.S. Procurement of Low Carbon Municipal Solid Waste Infrastructure in India through Public-Private Partnerships. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2018, 8, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, W.; Guo, J.; Zhao, X.; Skibniewski, M.J. Social Risk Factors of Transportation PPP Projects in China: A Sustainable Development Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018, 15, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.-X. Sustainable Winner Determination for Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects in Multi-Attribute Reverse Auctions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarchand, N.; Laishram, B. Sustainable Infrastructure Development Challenges through PPP Procurement Process: Indian Perspective. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2017, 10, 642–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivilä, J.; Martinsuo, M.; Vuorinen, L. Sustainable Project Management through Project Control in Infrastructure Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spraul, K.; Thaler, J. Partnering for Good? An Analysis of How to Achieve Sustainability-Related Outcomes in Public–Private Partnerships. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 485–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedrick, B.Z.E.; Long, P.W. Investment Motivation in Renewable Energy: A PPP Approach. Energy Procedia 2017, 115, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kościelniak, H.; Górka, A. Green Cities PPP as a Method of Financing Sustainable Urban Development. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 16, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba-Romero, F.; Liyanage, C.; Roumboutsos, A. Sustainable PPPs: A Comparative Approach for Road Infrastructure. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2015, 3, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Dawson, R.J.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Delgado, G.C.; Salisu Barau, A.; Dhakal, S.; Dodman, D.; Leonardsen, L.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Roberts, D.C.; et al. Six Research Priorities for Cities and Climate Change. Nature 2018, 555, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.M.; ElGohary, A.S. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in Smart Infrastructure Projects: The Role of Stakeholders. HBRC J. 2020, 16, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Chen, B.; Wang, H.; Zhu, D. Public–Private Partnerships as a Governance Response to Sustainable Urbanization: Lessons from China. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoann, V.; Fujiwara, T.; Seng, B.; Lay, C.; Yim, M. Assessment of public–private partnership in municipal solid waste management in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.T.; Wong, J.M.; Wong, K.K. A Public-Private People Partnerships (P4) Process Framework for Infrastructure Development in Hong Kong. Cities 2013, 31, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karji, A.; Woldesenbet, A.; Khanzadi, M.; Tafazzoli, M. Assessment of Social Sustainability Indicators in Mass Housing Construction: A Case Study of Mehr Housing Project. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasman, S.E.; Faulin, J.; Lera-López, F. Integrating Environmental Outcomes into Transport Public–Private Partnerships. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2014, 8, 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.G.; Arboleda, C.A.; Botero, S. A Proposal for Green Financing as a Mechanism to Increase Private Participation in Sustainable Water Infrastructure Systems: The Colombian Case. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adebayo, A.A.; Lulofs, K.; Heldeweg, M.A. Indicators, Strategies, and Rule Settings for Sustainable Public–Private Infrastructure Partnerships: From Literature Review towards Institutional Designs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129422

Adebayo AA, Lulofs K, Heldeweg MA. Indicators, Strategies, and Rule Settings for Sustainable Public–Private Infrastructure Partnerships: From Literature Review towards Institutional Designs. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129422

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdebayo, Abimbola A., Kris Lulofs, and Michiel Adriaan Heldeweg. 2023. "Indicators, Strategies, and Rule Settings for Sustainable Public–Private Infrastructure Partnerships: From Literature Review towards Institutional Designs" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129422

APA StyleAdebayo, A. A., Lulofs, K., & Heldeweg, M. A. (2023). Indicators, Strategies, and Rule Settings for Sustainable Public–Private Infrastructure Partnerships: From Literature Review towards Institutional Designs. Sustainability, 15(12), 9422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129422